Supporting Tech Founders—A Needs-Must Approach to the Delivery of Acceleration Programmes for a Post-Pandemic World

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Start-Up Accelerators

- They offer programmes that are in principle open to all, but are nevertheless highly selective [22].

- They provide seed capital (typically between $18,000 and $25,000) usually in exchange for equity (typically 4–8%) [24].

- They support start-ups grouped in cohorts or batches to provide training in an efficient way, promote peer learning and generate a competitive and high-demanding environment.

- The programme finishes with a graduation event or demo day [17].

2.2. The Accelerator Ecosystem in Europe

- There is no direct correlation between the number of accelerators in a country and its GDP. For example, Spain has a high number of accelerator programmes compared to some larger countries, such as France and Italy.

- Most accelerators in the EU are cross-sectoral and when there is a specific focus, it is usually based on the application of technologies in a given sector, such as Fintech, Agritech, Edtech, Cybersecurity or Smart cities.

- In the UK and France, most accelerators are concentrated in their capital cities, while in other countries (e.g., Spain and Sweden), programmes tend to be more distributed across the territory, although still anchored to large cities.

- Most of the accelerators focus on the following fields: Fintech, Agritech, Edtech, Cybersecurity or Smart cities.

2.3. Impact of the COVID-19 on Accelerators

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Empirical Context and Source of Data

3.2. Data Description

3.3. Data Collection

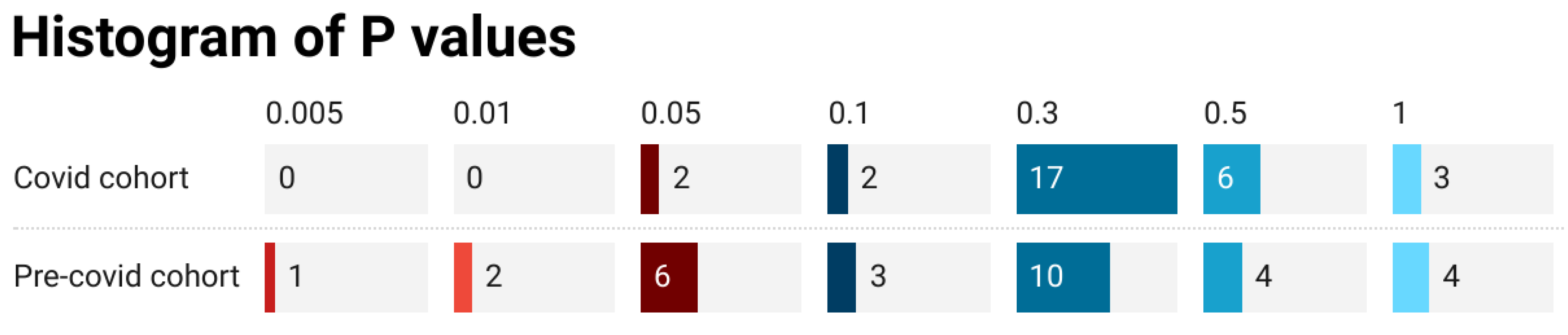

3.4. Data Validity Analysis

- The cohorts’ composition, in terms of the means of the values of the indicators and their variance, was similar in pre-COVID an into-COVID programmes.

- At programme entry, Technology was the category with the highest difference between cohorts, while Financial was the lowest.

- At programme exit, the differences between the indicators were reduced across all categories except Team and PR & Comms, in which all indicators differed.

- The evolution of the pre-COVID cohort (paired test) exceled over that of the COVID one in all categories.

3.5. Threats to the Validity of the Experiment

- The History effect refers to those events or factors that occur while the experiment is in progress and that are beyond the control of the experiment designer. Given the complexity of the objective of the experiment (to test the impact of COVID on the performance of start-ups participating in acceleration programmes) and the heterogeneity of the participants (business experience, level of education and network of contacts of the founders, technology used, level of income and maturity of the start-ups, etc.), it is very difficult to assess the impact of this effect on the validity of the results. This is precisely the objective of the statistical tests described in the previous section: to verify that the evolution of the indicators of the start-ups has been similar in all cases and that, therefore, regardless of the events that may have taken place while the experiment was underway, all participants have experienced a similar evolution after their passage through the acceleration programme.

- Maturation refers to how the passage of time and the experience participants gained in the programme can affect the outcome of the experiment. Since there is no control group, it is not possible to assess the effect of this threat directly. Again, the objective of the statistical tests is to check that the evolution of the indicators is independent of what has happened during the acceleration programme and is similar for all start-ups, in order to mitigate the effect of this threat. In addition, almost all start-ups had already participated in previous acceleration programmes, where they started the development of their business idea. Therefore, they had already acquired some of the knowledge that can be gained as part as their participation in an acceleration programme, so it is possible to assume that the maturation effect had already occurred to a large extent for almost all of them.

- Main testing and interactive testing effects occur as a result of participants being tested on entry and exit from the acceleration programme and affect participants’ posttest scores. This may be due to factors such as participants not understanding the questions well or not having experience with the scale used, wanting progress to be visible after the programme, paying more attention or trying harder knowing that they are being assessed, etc. In this sense, it has to be clarified that, from the beginning of the acceleration programme, it was indicated to participants that the purpose of the evaluation was to make them aware of their current status, of what goals they would have to achieve to improve in each of the 30 business-oriented indicators and of the progress they had experienced after their passage through the programme. In any case, to mitigate this effect, the scores given both at the beginning and at the end of the acceleration programme were agreed between the start-up and the IoT Tribe team. In this way, an attempt was made to maintain homogeneity in the evaluation.

- Mortality refers to the impact of participants dropping out of an experiment. In the case of the two acceleration programmes studied, only one start-up did not complete each of the programmes, which represents 5.26% in the pre-COVID programme and 4.76% in the into-COVID programme. The impact of these drop-outs was small as the samples were still of adequate size and there were no dependencies between participants that could reduce the performance of the start-ups that remained in the programme. Data from the start-ups that dropped out of the accelerator programmes have not been taken into account in this study.

4. Findings

- The intensity of the acceleration programmes, where founders are not fully immersed in an accelerator environment and cannot as easily draw on the accelerator team and resources as needed.

- The lack of face-to-face workshops limits the acquisition of knowledge as it is more difficult to interact to clarify or expand on themes of particular interest.

- On-line environments hindering the informal learning, socialising and support that accompany the founders who are part of the face-to-face cohort.

- The difficulty of effective networking where people engage in conversations that allow relationships to develop and where contacts made are better contextualised and more memorable than their virtual equivalents.

- The temporary moratorium on corporate budgets that emerged during the early stages of the pandemic, in which non-essential spending was frozen in many companies, essentially delaying any possibility of piloting new technologies.

- Zoom fatigue [49], a recognised phenomenon that has confirmed that burnout occurs after exposure to long periods of videoconferencing.

- The following sections describe the findings in each of the categories.

4.1. Technology

4.2. Product

4.3. Market

4.4. Team

4.5. PR & Communications

4.6. Financial

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Implications for Practice

- Virtual acceleration programmes attract more mature start-ups, as they can combine their day-to-day work with participation in the accelerator and even assign different members of the team to different parts of the programme.

- The barrier for participation from non-domestic start-ups is also lowered.

- Virtual programmes are also able to provide access to a broader range of mentors with specific technology or market expertise, reducing the friction inherent in finding free time and matching founders with the know-how they need.

- While during the pandemic founders were able to benefit from remote peer support and relationships with their fellow cohort members were established, these relationships lasted longer and run deeper when they are established in an in-person accelerator.

- While events designed to showcase the start-ups’ capability succeeded in attracting relatively large numbers of attendees during the pandemic, fatigue soon set in. The value of the contacts and connections made through in-person events was significantly higher.

- Market engagement can also be more effective in the early stages through remote channels (e.g., to establish whether the contact is the right person within the organisation and to obtain initial, high-level feedback) but more valuable information and longer-lasting contacts are obtained through in-person meetings.

- Similarly, in-person demo days resulted in better delivery of pitches, particularly for non-native English speakers, and engagement with investors more fruitful.

- Across both types of programmes, progress in the early stages is quicker than that in later stages, which may point to a need to deliver accelerators for scale-ups with a different cadence to the standard linear three months.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Business Category | Key Business Sub-Category | Criteria for Score = 1 | Criteria for Score = 2 | Criteria for Core = 3 | Criteria for Score = 4 | Criteria for Score = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TECHNOLOGY | 1.1 Maturity of Technology | Tech. in initial experimental phase | Tech. successful on a laboratory scale | Technology successful in live environment | Tech. commercially deployed (small scale) | Tech. commercially deployed (large scale) |

| 1.2 Advantages Compared to Competitive Technologies | No concrete advantages defined | Advantages identified but not quantified | Advantages identified and quantified | Advantages identified and quantified and evidence is available | Significant advantages identified and quantified and evidence is available | |

| 1.3 Architecture | No architecture identified or associated with design process | Basic architecture with part of the functionality at a high level of abstraction | High-level architecture of the design of the system | High and detailed level architecture for the whole system | Scalable and fully identifiable architecture adopted following well-known industry practice | |

| 1.4 Standards | No standards | Few standards have been considered in development phases | Standards have been considered occasionally in development phases and quality assurance | Standards have been considered in development phases and quality assurance | Standards have been considered in development phases and quality assurance in a systematic way | |

| 1.5 Performance | No metrics | Basic metrics for performance | Basic metrics for performance and scalability | Well-defined metrics for performance and scalability | Systematic consideration of well-defined metrics for performance and scalability | |

| 1.6 Cybersecurity & Resilience | No risk assessment | Ad hoc risk assessment | Basic risk assessment and mitigation plan available | Full risk assessment and mitigation plan available | Full and systematic risk assessment and mitigation plan available with resources assigned | |

| 2. PRODUCT | 2.1 Product Development | No methods, no process. Product developed ad hoc | Methodologies or process applied in some phases of development | Methodologies or processes applied in many phases of development | Use of well-known methods and processes to specify and design the whole system | Documentation available for all tech development and iteration/updating of processes for all phases |

| 2.2 Product | Characteristics developed on a tech first basis | Some characteristics developed with user needs loosely identified | Some characteristics developed with user needs identified on the basis of data | Most/all characteristics developed with user needs on the basis of data | Most/all characteristics developed with user needs on the basis of data and tested | |

| 2.3 Pricing | No consistent pricing parameters or consultancy pricing | Initial pricing strategy and parameters available | Pricing strategy and parameters associated with product attributes | Pricing strategy and parameters associated with product attributes and market segments | Pricing strategy and parameters associated with product attributes and market segments and cross or upselling strategies clear | |

| 2.4 Integration/Deployment | Do not yet understand the issues related to integration and/or deployment | Some understanding of the issues related to integration and/or deployment | Clear understanding of the issues related to integration and/or deployment | Clear understanding of the issues related to integration and/or deployment and some experience in dealing with them | Clear understanding and experience of the issues surrounding integration with legacy environments and existence of a methodology for identifying and addressing them | |

| 2.5 Scalability | No scalability | Potentially scalable but no plans defined | Route to scalability defined | Route to scalability defined and clear metrics established | Route to scalability defined and clear metrics established and are being met | |

| 3. MARKET | 3.1 Size | No clear real idea of the size of the addressable market size | Initial rough assessment of addressable market | Clear idea of addressable market | Clear idea of addressable market and the routes to the market | Clear idea of addressable market, the routes to the market and the priority segments |

| 3.2 Competition | No market intelligence performed | Some market intelligence performed but no clear or only partial advantages defined over competitors | Market intelligence performed ad hoc with advantages over competitors clearly defined | Market intelligence performed regularly with advantages over competitors clearly defined | Full market intelligence performed on a regular basis and response to competitors offerings is adjusted | |

| 3.3 Product–Market Fit | Unclear product–market fit | Initial product–market fit established | Product–market fit established and initial value proposition has been defined | Product–market fit established and value proposition is clear and strong | Product–market fit established and value proposition is clear and strong and differentiated from existing solutions on the market | |

| 3.4 Clients | No clients, paid or unpaid | Some contracts signed with clients for non-paying pilots | Some revenue-generating contracts signed with clients | Increasing number of revenue-generating contracts signed with clients | Increasing number of revenue-generating contracts signed with clients and full customer pipeline | |

| 3.5 Sales | No clear idea of client purchasing criteria and procurement process | Initial contact with clients and with insights into purchasing criteria and/or procurement process | Clear idea of client purchasing criteria and procurement process | Clear idea of client purchasing criteria and procurement process and at least one successful sale completed | Clear idea of client purchasing criteria and procurement process integrated into sales strategy and successful sales with several clients | |

| 3.6 Go-To-Market Strategy | Opportunistic approach to go-to-market | Proactive but ad hoc approach to go-to-market by core team | Go-to-market strategy has been developed | Go-to-market strategy has been developed and has a budget | Go-to-market strategy has been developed, has a budget and is being implemented by a dedicated person/team | |

| 4. TEAM | 4.1 Team Profile | Single founder | Several founders | Several founders will skills that address core business functions | Complete team with track record and technological expertise | Strong team with proven track record and technological and relevant domain expertise |

| 4.2 Skills Gap | Skill gap analysis has not been performed | A basic skill gap analysis has been performed | A full skill gap analysis has been performed | A full skill gap analysis has been performed and used to inform recruitment | Full skill gap analyses are performed systematically and are used to inform recruitment | |

| 4.3 Roles | No job descriptions are available | Job descriptions are available for some profiles | Job descriptions are available for all profiles | Job descriptions are available for all profiles and there is a formal recruitment process | Job descriptions are available for all profiles and there is a formal recruitment and evaluation process | |

| 4.4 Remuneration | No formal remuneration structure available | Basic remuneration structure available | Comprehensive remuneration structure available | Remuneration and career development plan for employees | Remuneration and development plan with a range of incentives to retain and reward employees | |

| 5. PR & COMMS | 5.1 Brand | The logo has not been professionally developed | The logo has been professionally developed but there are no brand guidelines | The logo has been professionally developed and there are brand guidelines | The logo has been professionally developed and there are brand guidelines that are consistently applied | The logo has been professionally developed and there is a recognisable brand with clear messages and values |

| 5.2 Marketing Collateral | There is no marketing collateral | Some marketing collateral (e.g., leaflets, social media campaigns) | Clearly defined marketing collateral and a marketing strategy | Clearly defined marketing collateral and a marketing strategy and budget | Clearly defined marketing collateral and a marketing budget implemented by a dedicated team (internal or external) | |

| 5.3 PR & Communications | No communication activities are carried out | Communication activities carried out on an ad hoc basis (e.g., press releases, blog posts) | Basic communication activities according to general guidelines online and off-line including presence at trade fairs | Full communication strategy available with budget assigned | There is a full communication strategy available linked to clear channels for brand awareness and comms metrics | |

| 6. FINANCIAL | 6.1 Financial Model | No financial model | Calculations are backed with simple, unverified assumptions | Calculations are backed with clear assumptions and forecasts | Calculations are backed with clear assumptions and forecasts and clear milestones linking income and/or expenditure | Calculations are backed with clear assumptions and forecasts and clear milestones linking income and/or expenditure and there is a track record of achievement |

| 6.2 Growth Metrics | No growth metrics have been defined | Basic growth metrics have been defined | Comprehensive body of growth metrics available | Comprehensive body of growth metrics available and regularly tracked | Comprehensive body of growth metrics available and regularly tracked and acted upon | |

| 6.3 Revenue | Pre-revenue with no monetization strategy | Pre- or post- revenue with a monetization strategy with no defined targets | Pre-revenue or consultancy revenue with a basic monetization strategy and/or targets that are not based on tested assumptions | Pre- or post-revenue with a clear monetization strategy with defined targets based on tested assumptions | Pre- or post-revenue with a clear monetization strategy that has been implemented and meeting targets | |

| 6.4 Valuation | Company has not been valued | Company has been valued without applying a recognized valuation methodology | Company has been valued internally applying a recognized valuation methodology | Company has been valued externally applying a recognized valuation methodology | Company valuation is clear and is backed by pre-money term sheets | |

| 6.5 Investment Strategy | No investment plan | Basic investment plan available | Comprehensive investment plan available | Comprehensive investment plan available with clear implementation timetable | Comprehensive investment plan available with clear implementation timetable regularly tracked and acted upon | |

| 6.6 Experience | Does not know what a term sheet is and has no experience in securing investment | Has limited experience in trying to secure investment | Has experience in trying to secure investment unsuccessfully | Has secured angel investment | Has secured VC investment | |

| 7. QUALITATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE FOUNDING TEAM | 7.1 Domain Knowledge | No knowledge of the target market | Some indirect knowledge of the target market or experience <2 years | Direct experience of target market 2–5 years | Direct experience of target market >5 years | Recognised expert in the field |

| 7.2 Entrepreneurial Spirit | Does not appear to possess the basic qualities of a founder | Demonstrates some entrepreneurial behaviour | Demonstrates entrepreneurial behaviour | Demonstrates entrepreneurial behaviour although not fully aware of risks and opportunities | Highly entrepreneurial mindset and spirit. Aware of risks and opportunities but still confident of success | |

| 7.3 Coachability | Does not appear to be able to take advice or criticism | Takes on external advice or criticism sporadically | Takes on external advice or criticism most of the time | Takes on external advice or criticism and analyses impact on company and takes action | Takes on external advice or criticism, contrasts with other inputs, analyses impact on company and takes action | |

| 7.4 Passion | Does not communicate with conviction or passion | Communicates with some conviction or passion | Communicates with conviction or passion inconsistently | Always communicates with conviction or passion | Capable of transmitting passion and generating interest in others |

Appendix B

| Acceleration Programme | Start-Up Code | Foundation Year | Start-Up Age (Years) | # of Founders | Nationality of Founders | Country of Incorporation | Technological Sector of Start-Up Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (2018) | A1 | 2015 | 3 | 1 | Italian | UK | Utilities |

| A2 | 2017 | 1 | 3 | Turkish | USA | Real Estate | |

| A3 | 2016 | 2 | 1 | Scottish | UK | ||

| A4 | 2017 | 1 | 2 | British | UK | Health | |

| A5 | 2016 | 2 | 2 | Brazilian, German | USA | Consumer Electronics | |

| A6 | 2017 | 1 | 2 | Colombian | UK | Utilities | |

| A7 | 2017 | 1 | 2 | British | UK | Industry | |

| A8 | 2016 | 2 | 4 | Polish, North American | PL | Transport & Logistics | |

| A9 | 2014 | 4 | 1 | Spanish | ES | Maritime | |

| A10 | 2017 | 1 | 1 | British | UK | Industry | |

| B (2019) | B1 | 2018 | 1 | 1 | Russian | NL | |

| B2 | 2018 | 1 | 1 | Polish | PL | Transport & Logistics | |

| B3 | 2018 | 1 | 2 | Pakistani | UK | Smart Manufacturing | |

| B4 | 2016 | 3 | 3 | British, Canadian | UK | Real Estate | |

| B5 | 2015 | 4 | 2 | British | UK | Smart Manufacturing | |

| B6 | 2015 | 4 | 1 | Finish | FI | Manufacturing | |

| B7 | 2013 | 6 | 1 | Russian | UK | Transport & Logistics | |

| B8 | 2018 | 1 | 2 | British, Portuguese | UK | Smart Manufacturing | |

| B9 | 2016 | 3 | 3 | Spanish | ES | Smart Manufacturing | |

| C (2020) | C1 | 2015 | 5 | 1 | Spanish | ES | Industry |

| C2 | 2018 | 2 | 3 | Spanish | ES | Aerospace | |

| C3 | 2017 | 3 | 2 | Romanian | RO | Financial Services | |

| C4 | 2015 | 5 | 1 | British | UK | Smart Cities | |

| C5 | 2019 | 1 | 2 | Russian | DE | Aerospace | |

| C6 | 2007 | 13 | 2 | Cypriot British | CY | Critical Infrastructure | |

| C7 | 2014 | 6 | 4 | Spanish | ES | Smart Cities | |

| C8 | 2019 | 1 | 1 | Irish | UK | Real Estate | |

| C9 | 2018 | 2 | 2 | French | FR | Healthcare | |

| C10 | 2019 | 1 | 2 | Spanish | ES | Aerospace | |

| C11 | 2013 | 7 | 2 | French | FR | Financial Services | |

| C12 | 2019 | 1 | 2 | Uruguayan | Uruguay | Aerospace | |

| C13 | 2016 | 4 | 1 | French | FR | Aerospace | |

| D (2021) | D1 | 2019 | 1 | 1 | British | UK | Industry |

| D2 | 2018 | 2 | 1 | German | DE | Industry | |

| D3 | 2018 | 2 | 2 | Spanish | ES | Industry | |

| D4 | 2013 | 7 | 2 | Belgian | BE | Smart Cities | |

| D5 | 2019 | 1 | 1 | French | FR | Transport | |

| D6 | 2017 | 3 | 4 | Italian | IT | Smart Cities/Agriculture | |

| D7 | 2016 | 4 | 1 | Spanish | ES | Aerospace | |

| D8 | 2020 | 0 | 1 | French | FR | Aerospace |

References

- World Bank. Global Economic Prospects, January 2022; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36519 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Volberda, H.W.; Khanagha, S.; Baden-Fuller, C.; Mihalache, O.R.; Birkinshaw, J. Strategizing in a digital world: Overcoming cognitive barriers, reconfiguring routines and introducing new organizational forms. Long Range Plan 2021, 54, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Quayson, M.; Sarkis, J. COVID-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small-enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, N.J.; Galanakis, C.M. Unlocking challenges and opportunities presented by COVID-19 pandemic for cross-cutting disruption in agri-food and green deal innovations: Quo Vadis? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kateb, S.; Ruehle, R.C.; Kroon, D.P.; Burg, E.; Huber, M. Innovating under pressure: Adopting digital technologies in social care organizations during the COVID-19 crisis. Technovation 2022, 115, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M.; Korosteleva, J.; Piscitello, L. Digital affordances and entrepreneurial dynamics: New evidence from European regions. Technovation 2021, 119, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z.; Wood, G.; Knight, G. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, S.A. International entrepreneurship in the post COVID world. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Viardot, E.; Nylund, P.A. Implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for innovation: Which technologies will improve our lives? Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teare, G.; Global Venture Funding and Unicorn Creation In 2021 Shattered All Records. Technol. Crunchbase News. 2021. Available online: https://news.crunchbase.com/news/global-vc-funding-unicorns-2021-monthly-recap/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Isabelle, D.A.; Del Sarto, N. How can accelerators in south America evolve to support start-ups in a post-COVID-19 world? Multidiscip. Bus. Rev. 2020, 13, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, G.; Gioconda, M.E.L.E.; Del Vecchio, P.; Gianluca, E.L.I.A.; Margherita, A.; Valentina, N.D.O.U. Threat or opportunity? A case study of digital-enabled redesign of entrepreneurship education in the COVID-19 emergency. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidgen, K.; Gümüsay, A.A.; Günzel-Jensen, F.; Krlev, G.; Wolf, M. Crises and entrepreneurial opportunities: Digital social innovation in response to physical distancing. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2021, 15, e00222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beňo, M. The advantages and disadvantages of E-working: An examination using an ALDINE analysis. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battistella, C.; De Toni, A.F.; Pessot, E. Open accelerators for start-ups success: A case study. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 20, 80–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Fehder, D.C.; Hochberg, Y.V.; Murray, F. The design of startup accelerators. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1781–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, K.; Mitchell, J.R.; Bhagavatula, S. Accelerator expertise: Understanding the intermediary role of accelerators in the development of the Bangalore entrepreneurial ecosystem. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 117–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, C.; Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Van Hove, J. Understanding a new generation incubation model: The accelerator. Technovation 2016, 50, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; Bound, K.; The Startup Factories. NESTA. 2011. Available online: https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/the-startup-factories/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Cohen, S.; Hochberg, Y.V. Accelerating Start-ups: The Seed Accelerator Phenomenon. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Hove, J.V. A look inside accelerators in the United Kingdom: Building technology businesses. In Technology Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation: Theory, Practice, Lessons Learned; World Scientific: London, UK, 2016; pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.P.; de Vries, H.; Harrison, G.; Bliemel, M.; De Klerk, S.; Kasouf, C.J. Accelerators as authentic training experiences for nascent entrepreneurs. Educ. + Train. 2017, 59, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempwolf, C.S.; Auer, J.; D’Ippolito, M. Innovation accelerators: Defining characteristics among startup assistance organizations. Small Bus. Adm. 2014, 10, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bone, J.; Allen, O.; Haley, C. Business Incubators and Accelerators: The National Picture; BEIS research paper no 7. UK; Department of Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fehder, D.C.; Hochberg, Y.V. Accelerators and the Regional Supply of Venture Capital Investment. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, F. Corporate Accelerators: A Study on Prevalence, Sponsorship, and Strategy. Master’s Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bańka, M.; Salwin, M.; Masłowski, D.; Rychlik, S.; Kukurba, M. Start-up accelerator: State of the art and future directions. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2022, 25, 477–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, M. European Activities Specific to Web Entrepreneurs; Report of EU; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salido, E.; Sabás, M.; Freixas, P. The Accelerator and Incubator Ecosystem in Europe; Telefónica Europe: Calle Ancha, Cádiz, 2013; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, F.; Nepelski, D.; Cardona, M. The Startup Europe Ecosystem. Analysis of the Startup Europe Projects and of Their Beneficiarie; EUR 29134 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-80358-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, J. The European Seed Accelerator Ecosystem. Accel. Assem. 2014, pp. 1–8. Available online: http://www.acceleratorassembly.eu/research (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Guttentag, M.; Davidson, A.; Hume, V. Does the acceleration works? Global Accelerator Learning Initiative, May 2021. Available online: https://www.galidata.org/publications/does-acceleration-work/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Rusu, V.; Roman, A.; Tudose, M.; Cojocaru, O. An Empirical Investigation of the Link between Entrepreneurship Performance and Economic Development: The Case of EU Countries. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.; Bone, J. Who Helps the Helpers? Resilience and Challenges of Business Accelerators and Incubators during the Pandemic in the UK. In Resilience and Challenges of Business Accelerators and Incubators during the Pandemic in the UK; Project Report; NESTA: London, UK, 14 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, R.; Johnston, W. The coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: Crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriluță, N.; Grecu, S.P.; Chiriac, H.C. Sustainability and employability in the time of COVID-19. Youth, education and entrepreneurship in EU countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIver-Harris, K.; Tatum, A. Measuring incubator success during a global pandemic: A rapid evidence assessment. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Engaged Management Scholarship, Cleveland, OH, USA, 13 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnayake, H.; Mack, C.; Cui, M.; Peters, G.; Koo, A.; Zhou, J.; Tong, I.; Saretzki, D.; Toh, A. How Companies Can Reshape Results and Plan for a COVID-19 Recovery; Ernst & Young Global Limited: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A.; Passiante, G. Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.P.C.R. Should Accelerators Move to an Online Model? Master’s Dissertation, Universidade Catolica Portugesa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. Available onlinehttp://hdl.handle.net/10400.14/35223 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Kuckertz, A.; Brändle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Reyes, C.A.M.; Prochotta, A.; Steinbrink, K.; Berger, E.S. Startups in times of crisis-A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvi, A.; Mäkilä, T.; Hyrynsalmi, S. Game Development Accelerator-Initial Design and Research Approach; IW-LCSP@ ICSOB: Potsdam, Germany, 2013; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalainen, A.; Eriksson, P. Qualitative methods in business research: A practical guide to social research. In Qualitative Methods in Business Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781446273395. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber, S.N.; Leavy, P. Focus group research. In The Practice of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 163–192. ISBN 9781452268088. [Google Scholar]

- Levene, H. Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling; Stanford University Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mann Henry, B.; Whitney Donald, R. On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ratan, R.; Miller, D.B.; Bailenson, J.N. Facial appearance dissatisfaction explains differences in Zoom fatigue. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | F6S | Crunchbase | Country | F6S | Crunchbase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 7 | 14 | Italy | 58 | 58 |

| Belgium | 41 | 25 | Latvia | 2 | 3 |

| Bulgaria | 11 | 4 | Lithuania | 3 | 9 |

| Czech Republic | 5 | 7 | The Netherlands | 31 | 54 |

| Croatia | 5 | 3 | Malta | 3 | 0 |

| Cyprus | 4 | 2 | Poland | 12 | 19 |

| Denmark | 7 | 16 | Portugal | 22 | 37 |

| Estonia | 12 | 10 | Romania | 24 | 13 |

| Finland | 13 | 23 | Slovakia | 1 | 5 |

| France | 47 | 87 | Slovenia | 4 | 3 |

| Germany | 84 | 113 | Spain | 57 | 103 |

| Greece | 9 | 5 | Sweden | 11 | 17 |

| Hungary | 12 | 14 | Luxembourg | 4 | 6 |

| Ireland | 11 | 26 | UK | 135 | 238 |

| Concept | DE | UK | FR | IT | ES | NL | PL | SE | BE | IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total GDP (USD billion) | 4223.11 | 3186.85 | 2937.47 | 2099.88 | 1425.28 | 1018 | 674.08 | 627.43 | 599.87 | 498.55 |

| Population | 83.129 | 67.326 | 67.499 | 59.066 | 47.326 | 17.533 | 37.781 | 10.415 | 11.59 | 5.028 |

| (M people) | ||||||||||

| GDP per capita (USD) | 50,801 | 47,334 | 43,518 | 35,551 | 30,115 | 58,061 | 17,840 | 60,239 | 51,767 | 99,152 |

| Acceleration programmes | 84 | 135 | 47 | 58 | 57 | 31 | 12 | 11 | 41 | 11 |

| (F6S) | ||||||||||

| Acceleration programmes rate per 1 K inhabitants (F6S) | 10.1 | 20.1 | 7 | 9.8 | 12 | 17.7 | 3.2 | 10.6 | 35.4 | 21.9 |

| Share according to F6S | 17.25% | 27.72% | 9.65% | 11.91% | 11.70% | 6.37% | 2.46% | 2.26% | 8.42% | 2.26% |

| Acceleration programmes (Crunchbase) | 113 | 238 | 87 | 58 | 103 | 54 | 19 | 17 | 25 | 26 |

| Acceleration programmes rate per 1 K inhabitants | 13.6 | 35.4 | 12.9 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 30.8 | 5 | 16.3 | 21.6 | 51.7 |

| (Crunchbase) | ||||||||||

| Share according to Crunchbase | 15.30% | 32.20% | 11.80% | 7.80% | 13.90% | 7.30% | 2.60% | 2.30% | 3.40% | 3.50% |

| Research Article | Acceleration Phenomenon Analysis | Acceleration Model Proposal | Acceleration Model in Practice | Performance Metrics | Impact of COVID on Accelerators | Region | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isabelle and Del Sarto (2020) [11] | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | South America | Accelerators, COVID world, Start-ups, Entrepreneurship, Accelerator model, South America | ||

| Batistella et al. (2017) [16] | ☑ | Europe | Case studies, Open innovation, Business failures, Accelerators, Start-ups | ||||

| Cohen et al. (2019) [17] | ☑ | USA | Entrepreneurship, Startups, Startup programmes | ||||

| Goswami et al. (2018) [18] | ☑ | India | Accelerators, entrepreneurial ecosystems, entrepreneurial expertise, ecosystem intermediation | ||||

| Pauwels et al. (2016) [19] | ☑ | Europe | Incubation models, Accelerators, Activity system perspective, Design | ||||

| Cohen and Hochberg (2014) [21] | ☑ | USA | |||||

| Bone et al. (2017) [25] | ☑ | UK | |||||

| Chowdhury and Bone (2021) [35] | ☑ | UK | Accelerators, Incubators, UK, COVID, Pandemic, Brexit | ||||

| McIver-Harris and Tatum (2020) [38] | ☑ | ☑ | ☑ | USA | Business incubator, COVID, Performance, Entrepreneur, Metrics | ||

| Järvi et al. (2013) [43] | ☑ | ☑ | Canada | Game business, Lean start-up, Start-up accelerator, Game development | |||

| Clarysse et al. (2016) [22] | ☑ | UK | Incubators, Accelerators, High-tech startups, Microfinance |

| Programme | Year | Cohort Size | Graduated | Median Age of Company at Start | Av. No. of Founder | Target Markets | Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Tech I | 2018 | 10 | 9 | 1.5 | 1.9 | Real Estate | Health | | Artificial Intelligence | IoT | Augmented Reality/Virtual |

| Consumer Electronics | Utilities | Transport & Logistics | Maritime Industry | Reality | ||||||

| Industrial Tech II | 2019 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 1.8 | Transport & Logistics | Smart Manufacturing | Real Estate | Artificial Intelligence | IoT | |

| 3D printing | Cybersecurity | Digital Twins | Drones | |||||||

| Space Tech I | 2020 | 13 | 12 | 3 | 1.9 | Smart Cities | Aerospace | | Artificial Intelligence | IoT | Augmented Reality/Virtual |

| Critical Infrastructure| | Reality | Earth Observation | | ||||||

| Real Estate | Healthcare | Financial Services | Satellites | ||||||

| Space Tech II | 2021 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1.6 | Industry | Smart Cities |Transport | Smart Cities | Agriculture | Aerospace | Artificial Intelligence | IoT | Earth Observation | Satellites | Advanced materials | |

| Cybersecurity |Quantum |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suárez, T.; Iborra, A.; Alonso, D.; Álvarez, B. Supporting Tech Founders—A Needs-Must Approach to the Delivery of Acceleration Programmes for a Post-Pandemic World. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053130

Suárez T, Iborra A, Alonso D, Álvarez B. Supporting Tech Founders—A Needs-Must Approach to the Delivery of Acceleration Programmes for a Post-Pandemic World. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(5):3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053130

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuárez, Tanya, Andrés Iborra, Diego Alonso, and Bárbara Álvarez. 2023. "Supporting Tech Founders—A Needs-Must Approach to the Delivery of Acceleration Programmes for a Post-Pandemic World" Applied Sciences 13, no. 5: 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053130

APA StyleSuárez, T., Iborra, A., Alonso, D., & Álvarez, B. (2023). Supporting Tech Founders—A Needs-Must Approach to the Delivery of Acceleration Programmes for a Post-Pandemic World. Applied Sciences, 13(5), 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053130