Abstract

Student eXperience (SX) is a particular case of Customer eXperience (CX). It consists of all the physical and emotional perceptions that a student or future student experiences in response to interaction with products, systems, or services provided by a Higher Education Institution (HEI). SX has three dimensions: (1) social, (2) educational, and (3) personal. Currently, there is a lack of studies that address cultural aspects as an impact factor in the SX dimensions. The development of a model that encompasses these aspects would serve to develop solutions that improve the quality of education and the student’s overall well-being. A holistic SX model would better address the student’s environmental problems, and the SX evaluation. We present a proposal for a holistic SX model focused on undergraduate students that includes culture as a factor related to the SX dimensions. This model allows for developing holistic student solutions that could increase the HEIs perceived quality, student academic performance, and retention rates.

1. Introduction

The Student eXperience (SX) concept consists of all the physical and emotional perceptions and responses that a student or future student experiences in reaction to interaction with the products, systems, or services provided by a Higher Education Institution (HEI), as well as the interactions with people related to them, both inside and outside of academic spaces [1]. SX is derived from Customer eXperience (CX), of which it is a special case. This is because, during their academic life, students are consumers of HEI’s products, systems, and/or services.

SX has acquired great relevance due to the COVID-19 health crisis and the constant worldwide migratory waves. This occurs due to the inherent needs of current educational systems: the need to improve the quality of education, improve the positioning of HEIs, and improve overall student satisfaction. Despite the relevance that the concept has acquired, there is no generally agreed definition of SX in the literature.

Due to the need to have a formal SX definition with a focus on CX and to detect the dimensions and factors that influence it, a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was carried out in relation to the SX concept, their evaluation methods, and their factors/attributes. As a result of the SLR, a definition of SX was suggested, and three dimensions were detected, each one influenced by various factors of the students’ academic and non-academic environment: (1) social, (2) educational, and (3) personal. Detection of these elements makes it possible to develop solutions that improve student satisfaction by considering aspects that may influence their interactions and reactions. The possibility of expanding or refining our SX model and developing a holistic model that includes some elements that can optimize student satisfaction is evident.

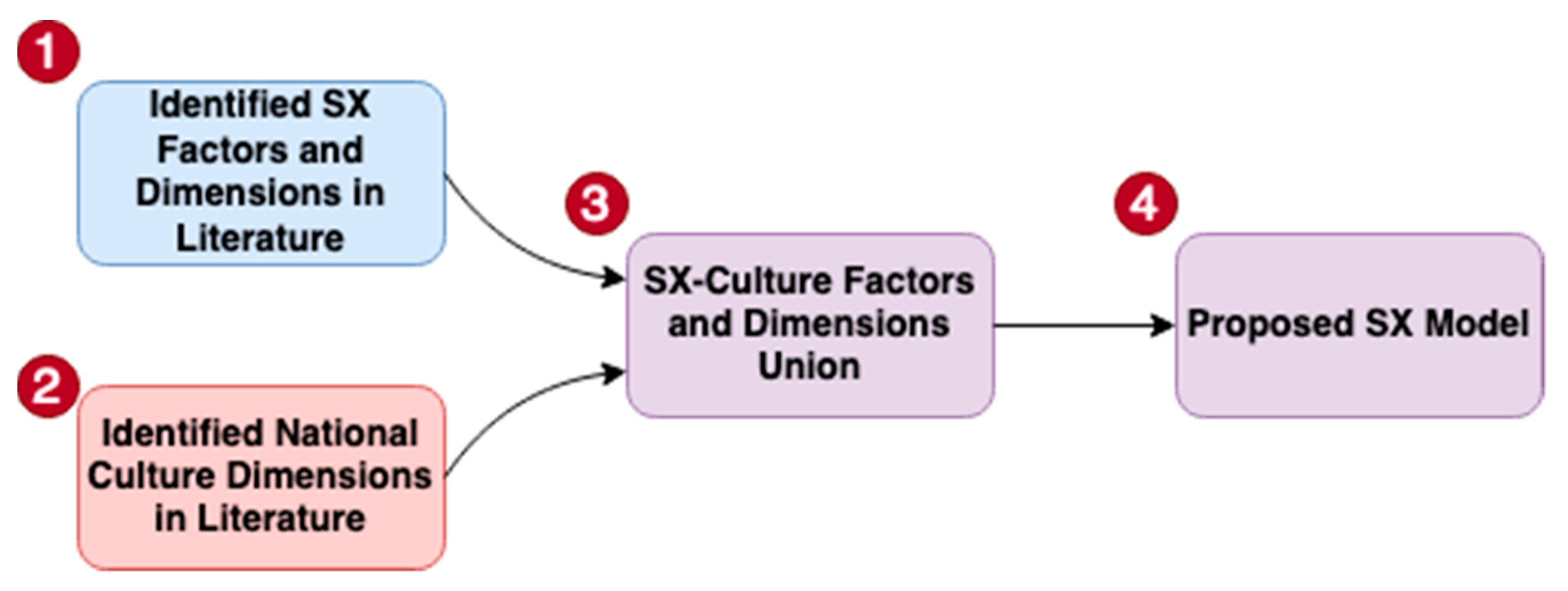

We believe that the national culture plays a vital role in the academic and non-academic life of students, such as performance in certain disciplines [2] or the student adaptation process in their first academic year. Culture could also be directly related to student subjective well-being [3] and mental health. Bearing in mind that cultural aspects are usually manifested in the SX dimensions, we have set out to develop a SX model that explicitly incorporates cultural aspects, focusing on undergraduate students. In this way, student solutions could better meet their needs by considering the aspects inherent to them. Moreover, the perceptions and expectations of people about certain events usually vary from culture to culture. The development of a SX model that incorporates cultural aspects consists of a four-stage process. The model could be used to develop a wide range of SX solutions and tools. The proposed model is theoretical and aims to identify the factors, relationships, and conceptual links between culture and SX. It is based on previously validated models, such as the Hofstede national culture model [4], and literature from related fields.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical background and concepts key to understanding our proposal. Section 3 presents the related work. Section 4 presents an analysis of cultural aspects in the SX dimensions. In Section 5 we present the definition of the SX dimensions and a matrix that relates the factors of the SX and the Hofstede national culture model. In Section 6 we include the limitations of our work. Finally, in Section 7, conclusions and future work are presented.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. User eXperience (UX)

The concept of user experience (UX) refers to the subjective perceptions of the use of goods and services by a user in a specific context. The UX concept is defined by the ISO 9241-210 standard as “the person’s perceptions and responses resulting from the use and/or anticipated use of a product, system or service.” UX incorporates some factors such as emotions, personal beliefs/preferences, physiological/psychological responses, behaviors, and perceptions before/after consumption [5].

UX is closely related to the Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) field [6] since the ways in which users interact with digital products is a novelty compared to previous decades. This is important considering that modern students are users of computer systems provided by HEIs, so UX (and Customer eXperience) educational solutions must consider interactions with technological media with approaches from an HCI perspective.

2.2. Customer eXperience (CX)

The CX concept extends the analysis of user interactions with a single UX product, system, or service to all interactions with a brand, across the products, systems, and services it offers. These concepts are relevant in our study since, as customers, students are users of the services, products, and systems offered by higher education institutions (HEIs).

The CX term is widely used today in areas such as marketing, psychology, sociology, design, computer science, and HCI. Despite this, it does not have a unique standardized definition. CX has been defined as the “physical and emotional experiences occurring through the interactions with the product and/or service offering of a brand from point of first direct, conscious contact, through the total journey to the post-consumption stage” [7]. Lemon and Verhoef, on the other hand, defined CX as a “multidimensional construct focusing on a customer’s cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensory, and social responses to a firm’s offerings during the customer’s entire purchase journey” [8]. Any SX proposal from a CX perspective must consider aspects of consumers’ lives, since their interactions, expectations, and perceptions tend to be subjective. The CX evaluation process is more complex than the UX one, also considering that CX analyzes multiple interactions in a much broader (time) consumption horizon than UX.

Gentile et al. (2007) suggest that CX has six dimensions [9]: (1) the emotional dimension, which involves the affective system, through the generation of moods, feelings, and emotions; (2) the sensory dimension, which involves stimulation that affects the customers senses; (3) the cognitive dimension, which is involved in conscious and thinking mental processes; (4) the pragmatic dimension, which is involved in the practical act or process of doing something; (5) the lifestyle dimension, which is related to the values, thoughts, beliefs, and lifestyles behaviors of a person; and (6) the relational dimension, which involves the person, in addition to his social context and relationships with other people. We find it pertinent to use this CX model because it incorporates the main types of value for customers [10], among which we could classify students based on consumption focused on efficiency, excellence, status, ethics, or spirituality. This is based, not necessarily on the disciplines that the student studies in the HEIs, but also on the personal motivations to study and their enthusiasm towards the contracted service.

2.3. Student eXperience (SX)

The Student eXperience (SX) is a widely used concept, which lacks a general agreement regarding its meaning [11]. The given use of the concept usually has relevance in specific contexts. Even so, the concept of SX is clearly related to the satisfaction and needs of students. Since its inception, it has been used mainly in academic environments, but over time it has been observed that SX includes aspects that go beyond the classroom and reach aspects of the students’ daily life. Douglas et al. (2008) defined SX within the academic area as the “experience of higher education teaching, learning and assessment and their experience of other university ancillary service aspects” [12]. As mentioned, the concept has been used outside the academic sphere. This is the case with some authors who use the “total student experience” concept to refer to students’ experiences in broader contexts than the classroom [13,14].

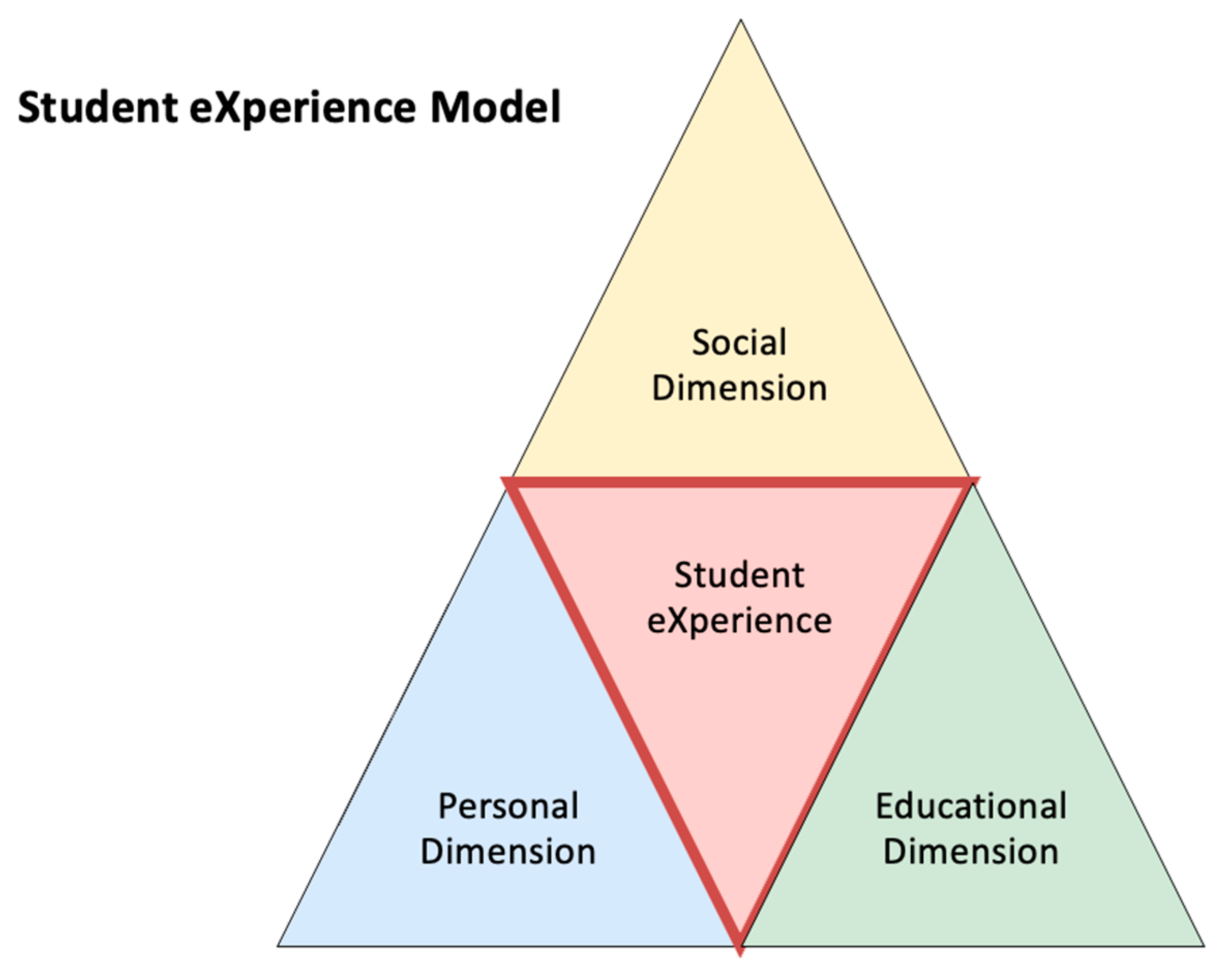

We recently carried out a SLR on the SX concept [1]. As a result of this work, it was possible to define the concept from a CX perspective, where the students are a particular type of customer. In this way, the SX are all the physical and emotional perceptions and reactions that a student or future student experiences in response to interaction with the products, systems, or services provided by a HEI, and interactions with people related to the academic field, both inside and outside of academic space. In this SLR we also identified that SX has three dimensions (see Figure 1). This is based on the factors commonly treated in investigations in the educational field and student experience evaluation methods. The three SX dimensions are:

Figure 1.

Student eXperience dimensions.

- Social: This dimension is related to community relationships and institutional engagement. Although students constantly interact with people in a society, this dimension focuses on interpersonal relationships within HEIs (student–student) and especially interactions with staff (student–administrative and student–educator for example). Along with the interactions, this dimension analyzes the feeling of institutional belonging, or engagement, of the students.

- Educational: This dimension is related to Students’ Learning Engagement, Higher Education Quality, Learning Resources/Learning Environment, and Educational/Support Services. This dimension encompasses any aspect that focuses on promoting an adequate educational environment or maximizing the educational outcomes of students (teaching methodologies, technological infrastructure, educational support networks). Consequently, these aspects translate into a positive perception of the quality of the HEI, which is why quality has been incorporated into this dimension.

- Personal: This dimension is related to student development and outcomes, student feelings and emotions, environment relationship, student thoughts, and students’ identity and background. Personal aspects of each student’s life that may influence interactions and perceptions with HEI services and products are considered. This dimension encompasses aspects related to culture, socioeconomic level, disabilities, personal aspirations, family structure, and leisure, among others.

In the detected SX dimensions in the literature, poor analysis of cultural aspects was observed. We consider this a problem since cultural aspects are especially relevant in SX. This is in view of the role played by cultural capital in studies (learning outcomes) and the cultural identity of international students in their personal adaptation process [15,16,17].

Culture acts transversally at the level of various factors that make up the SX, as evidenced in later sections. SX includes, per se, factors related to retention rates [18,19] and academic performance [20]. Solutions that seek to improve student satisfaction also have a direct impact on the quality perceived by students, since satisfaction is noted as an indicator of quality in HEIs [13,21]. In addition, some technological solutions can have a positive influence on students’ perceptions and, therefore, on their satisfaction. Culture has been related to the technological interaction of consumers with some of these solutions [22,23,24,25]. In this way, culture may influence students’ psychopedagogical aspects, which could influence the HEIs perceived quality based on academic performance, retention rates, and direct evaluation by students.

As a result of this, we propose an SX model that incorporates traditionally ignored cultural elements to subsequently develop tools that allow for better SX evaluation and support.

This model focuses on undergraduate students in HEIs. The use of this model at higher levels, such as graduate or postgraduate studies, may not effectively reflect the real needs and expectations of students.

2.4. Culture

Culture is a fundamental element in our societies. Analyzing culture could help to explain the way in which students relate to their environment and perceive external stimuli. Hofstede (2001) defined culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” [4].

The cultural factors analysis is especially important in the cases of refugee and exchange students. This is because these students are more likely to have culture shock when their values come into conflict with those of the local people. Also, understanding students’ cultural background plays an important role when implementing teaching methodologies and promoting HEI inclusion policies.

The cultural dimensions used to develop our SX model correspond to those of Hofstede’s National Culture model [4]. Hofstede’s national culture dimensions were developed in 1980 from the results of a large perception survey of workers in IBM offices, conducted between the 1960s and 1970s. The results of the surveys were subjected to statistical factor analysis by Hofstede, who was able to establish causal relationships between the behaviors and perceptions of people belonging to specific national cultures, defining four initial national culture dimensions. In 1991, Chinese sociologists conducted a cultural study that established a national culture dimension referring to the long-/short-term orientation of individuals in a society [26]. Hofstede included this dimension in his model later [27]. The addition of the sixth national culture dimension, referring to indulgence and restraint, and the verification of the previous five dimensions was carried out after Minkov’s studies on data from the World Values Survey [28].

The choice of Hofstede’s cultural model is because it has been widely validated after multiple practical applications. Additionally, this model has incorporated more dimensional elements over time [29] and the dimensions of other cultural models have a direct (correlational) relationship with the dimensions proposed by Hofstede [30,31,32].

CX or UX solutions that incorporate cultural factors are not new [33]. The positive results in the industry when considering cultural elements in solutions have been an incentive to develop an SX model that includes cultural dimensions. Table 1 details the six national culture dimensions proposed by Hofstede and their respective abbreviations.

Table 1.

Hofstede’s national culture dimensions.

The identification of SX cultural aspects allowed us to analyze the satisfaction or dissatisfaction that students experience throughout their university life. In simple terms, studying the cultural factors involved in students’ interactions with HEIs gives us important insights into how we can improve their holistic experience. This is ideally framed in an SX evaluation process.

3. Related Work

Carrying out our SX model with cultural aspects required defining the SX and national culture factors to incorporate. Regarding the SX factors to be incorporated into the model, these were based on a SLR on the concept of SX, the factors and dimensions that constitute it, and its traditional evaluation methods. Prior to our SLR, we worked on nonsystematic reviews on the SX concept [11] and the emotional aspects of SX (part of the third dimension of SX) [34]. Additionally, we analyzed a national SX in a crisis study case (Chile) [35], and a preliminary analysis of the cultural aspects present in the SX [36]. As a result of our reviews, we did not find a pre-existing SX model, much less one that incorporates cultural aspects. This certainly favors the impact of our SX model proposal.

Regarding the cultural factors to incorporate in our proposed model, we have chosen to use Hofstede’s’ national culture dimensions [4,29]. The reason for this is that the dimensions of traditional cultural models usually have a direct correlation with the dimensions of Hofstede’s model [30,31,32,37]. In this regard, we should point out that the focus on a specific cultural model is not a problem. This is because existing cultural models often share common elements. In this way, culture is usually analyzed as a multilevel and multidimensional phenomenon. Furthermore, in cultural models it is generally agreed that culture refers to a set of stable values widely diffused in a society over a relatively long time [4,37].

The use of the Hofstede model has the advantage of having several investigations associated with the educational field that can help complement our proposal. Some examples of this are a study that relates the Hofstede dimensions of LTO and IVR with the academic performance of students [2]; a study that analyzes the LTO, IDV, and UA with respect to teaching methodologies [38]; a study that relates the cultural dimensions of Hofstede with respect to online learning [39]; and a study that analyzes the dimensions of UA and PD regarding the student learning process [40].

4. Analysis of Cultural Aspects in the SX Dimensions

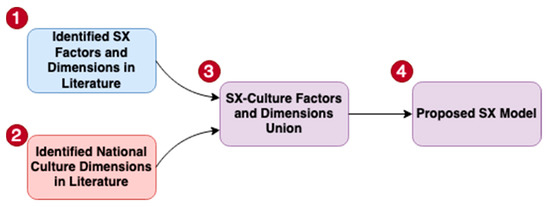

The SX culture model development consists of a four-stage process (Figure 2): (i) the compilation of bibliographic material and the identification of SX dimensions and factors; (ii) the identification of factors and dimensions of the national culture in the literature; (iii) union of the factors and dimensions of the SX and the national culture models; and (iv) the consolidation of the model with the common SX cultural elements.

Figure 2.

Student eXperience model development stages.

As part of the third stage of the model development process, we carried out a factor-by-factor analysis of the elements that make up the cultural and SX models. We analyzed the relationship of people in a society with respect to culturally diverse topics such as general norms, gender, and family, and related them to the SX dimensions that could be influenced by them (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6). In doing so, we have been guided by the elements identified by Hofstede referring to each national culture dimension and the factors that make up each SX dimension.

Table 2.

General norm, family, school, and healthcare aspects of power distance in SX.

Table 3.

General norm and family of individualist/collectivist societies in SX.

Table 4.

Gender and sex in SX.

Table 5.

General norms and family aspects of long-term orientation societies in SX.

Table 6.

General norm, personal feelings, and health aspects of indulgence/restraint societies in SX.

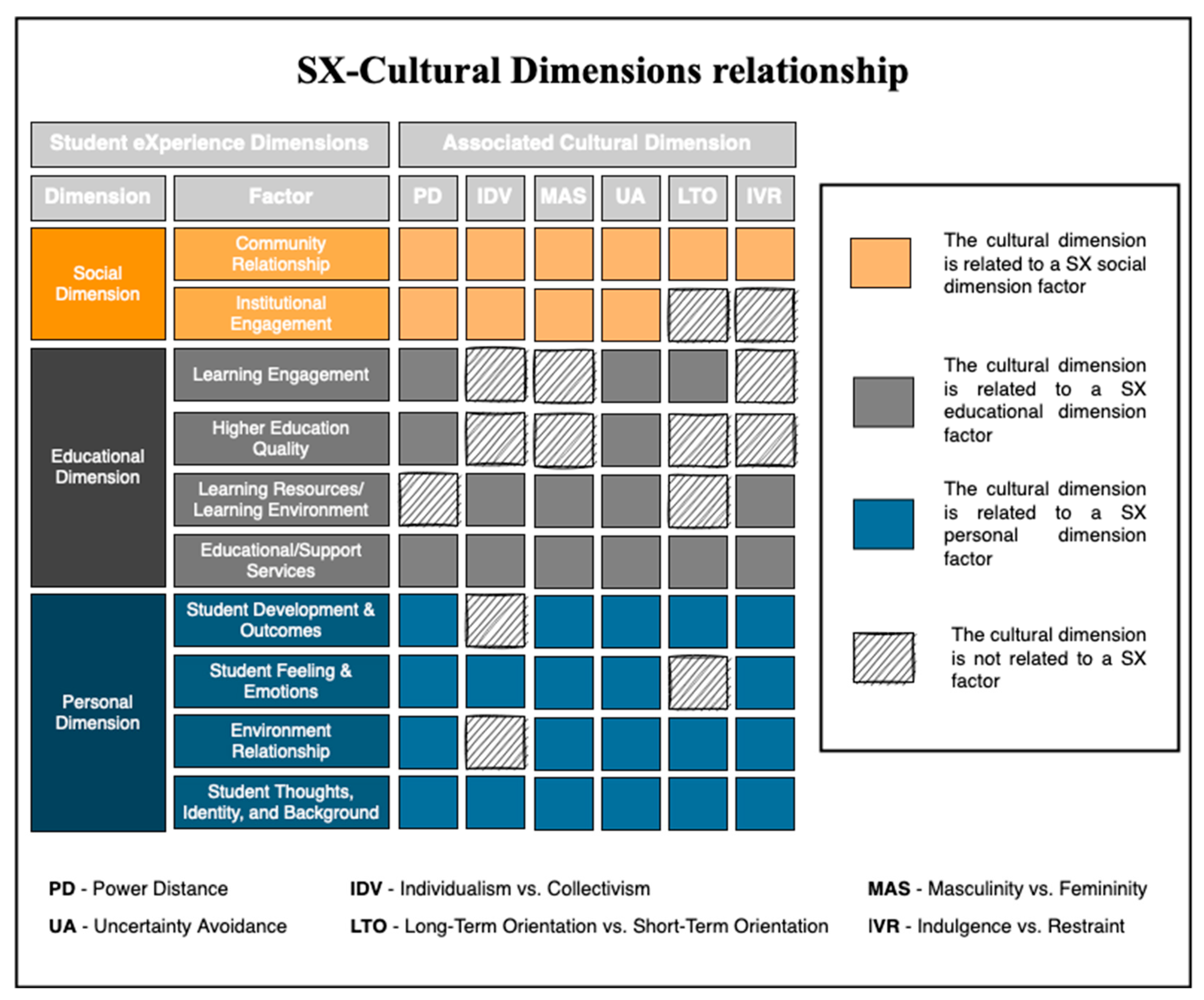

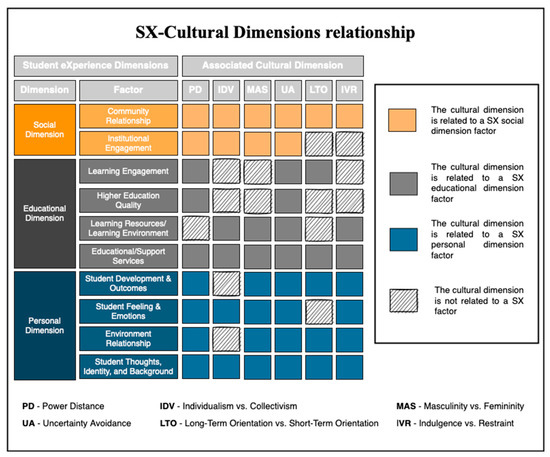

After this analysis, we developed a matrix that allows us to see the relationship between cultural aspects and SX dimensions (Figure 3). With the matrix, it is clear what SX factors are influenced by specific cultural elements. This matrix was finally used to integrate the cultural aspects to a new SX model.

Figure 3.

SX cultural dimensions relationship.

It is important to note that the proposed model is theoretical. Its validation must be empirically verified through practical application, expert judgment, and statistical methods. Future work contemplates the development of a practical SX evaluation methodology and the development and systematic application of a scale that incorporates cultural aspects.

4.1. Power Distance (PD) and Student eXperience

Hofstede defines Power Distance (PD) as “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” [29]. Within his conception of an institution, as basic elements within a society, he considers schools. By extension of that concept, the Power Distance can be seen in HEI, such as universities and colleges. This concept is related to the subject’s perception of an authority figure. The subjects in an organization can perceive paternalistic or autocratic treatment, to a greater or lesser extent. The relationship between subjects of different levels of authority is related to the dependency between people. Additionally, the emotional distance between subjects determines the degree of communication. This is because the degree of fear of the subordinates defines the ease of approaching and contradicting authorities directly.

The Power Distance Index (PDI) indicates the degree of dependency of subjects under an authority figure in an organization/institution within a country. For a student from a country with a PDI score very different from that of the new country of residence, there could be culture shock. Consequently, anxiety or discomfort could be generated that could affect the perceived quality and satisfaction with respect to the services provided by an HEI.

Within an HEI, there may be student–teacher or student–administrator relationships. Considering the hierarchical structure of the institutions and the services they provide, we believe that the Power Distance is mainly related to the Institutional Engagement in the social dimension of the SX; the relationship of the students with the Educational/Support Services in the educational dimension; and the Student Feelings and Emotions, and Student Development and Outcomes in the personal dimension. To a lesser extent, the distance to power could be evidenced in the student’s Community Relationship, in the social dimension, and in the environmental aspects in the educational and personal dimension, in situations in which they interact with subjects in a high position in the HEI.

Studies related to Power distance have been conducted on subjects not necessarily directly involved in business settings. This includes the use of students as test subjects [30]. It has been observed that students scoring high on power distance tend to have thoughts related to “Having few desires,” “Moderation, following the middle way,” and “Keeping oneself disinterested and pure.” Students in countries scoring low on power distance tend to have thoughts related to “Adaptability” and “Prudence.” It is important to mention that it has been observed that student power distance affects classroom activity and interaction [41]. In this way, the importance of analyzing this cultural dimension is evident when developing solutions that aim to improve the SX.

Table 2, built from the empirical analysis of the PD elements, relates the general norm, family, school, and healthcare values to the factors that make up the SX dimensions.

4.1.1. Power Distance in Student eXperience: Social Dimension

In the social SX dimension, the distance to power is evidenced mainly by institutional engagement. This is because student engagement is strongly linked to the degree of trust inspired by authority figures, such as teachers and high-ranking administrators. In this way, it will be more difficult for students to engage with HEIs if they perceive autocratic treatment. This is especially important when we consider students from countries with low PDI in countries that have a higher PDI score. Additionally, when students associate power distance with adaptability, this dimension is related to the Community Relationship aspect of the social dimension of SX. This is because the student’s adaptation process takes place in part with respect to the university community.

4.1.2. Power Distance in Student eXperience: Educational Dimension

In the educational dimension of the SX, the distance to power is evident with respect to the Educational/Support Services. This is because students may perceive paternalistic treatment by student support services. This, depending on the cultural background of the students, can cause a negative reaction, in terms of emotions and satisfaction. Furthermore, in the words of Hofstede, “effective learning in such a system depends very much on whether the supposed two-way communication between students and teacher is, indeed, established.”

The PD is also related to the perceived quality of education, since quality of learning, which is related to HE quality, is determined by the excellence of the students. This value is strongly associated with the PD values related to adaptability and desires.

4.1.3. Power Distance in Student eXperience: Personal Dimension

As PD is associated with the desire for progress within the institution, it is related to the “Student Development and Outcomes” aspect of the personal dimension of the SX. Additionally, like the desire for power in the social dimension, when students associate power distance with adaptability, this dimension is related to the Environment Relationship aspect but at a personal level, not strictly in an academic setting.

The PD is also related to the Student Feelings and Emotions of the SX personal dimension. This is because, in one way or another, the feelings caused by an autocratic or paternalistic figure in their immediate environment (not necessarily academic) will have an impact on their state of mind and their expectations of their environment.

4.2. Individualism/Collectivism (IDV) and Student eXperience

The dimension of individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) is defined based on the two central concepts: Individualism and Collectivism, which are opposites. Hofstede details that “Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him- or herself and his or her immediate family. Collectivism as its opposite pertains to societies in which people from birth onward are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.” In this way, it is evident that this dimension is present in instances in which the student is part of or is affected by group processes. This occurs in the classroom, when working on group projects; in relation to processes that require reaching consensus between students and teachers or students and educational authorities; and in processes of the student’s personal life, contained in the personal dimension of the SX.

As result of the individual subjects’ data collected in the Hofstede study, he identified some work goals. These are: (1) personal time, which refers to having a job that leaves sufficient time for family life and leisure; (2) freedom, which refers to having enough freedom to adopt a personal job approach; and (3) challenge, which refers to having challenging work and tasks to do in which a sense of personal accomplishment could be achieved.

Regarding collectivist individuals, elements related to the following work goals were detected: (4) training, which refers to having work training opportunities (to improve skills or learn new skills); (5) physical conditions, which refers to good physical working conditions (good ventilation and lighting, adequate workspace, etc.); and (6) use of skills, which refers to fully using skills and abilities on the workplace. Although these data were originally collected from the opinions of IBM employees by Hofstede, later works in the field of culture defined dimensions such as those detected by Hofstede and with a high degree of correlation in their results [29].

As with the cultural dimension related to power distance, because of studies that replicated Hofstede’s work with test subjects related to the academic world, phenomena that are directly related to SX dimensions were detected. Students with a high index of individualism found the following values particularly important: (1) “tolerance of others,” (2) “harmony with others,” (3) “noncompetitiveness,” (4) “a close, intimate friend,” (5) “trustworthiness,” (6) “contentedness with one’s position in life,” (7) “solidarity with others,” (8) and “being conservative.” Regarding students with a rather collectivist background, they found the following important values: (9) “filial piety (obedience to parents, respect for parents, honoring of ancestors, financial support of parents),” (10) “chastity in women,” and (11) “Patriotism” [30]. Regardless of the pole to which these values belong (Individualism or Collectivism), they can be related to aspects of the SX dimensions. All of them are manifested directly or indirectly in situations of collective action. For this reason, the cultural dimension related to collectivism vs. individualism is observed in the Community Relationship aspect of the SX social dimension, in the Resources/Learning Environment and Educational/Support Services aspects of the SX Educational dimension, and in the Student Feelings and Emotions and Student Thoughts, Identity, and Background aspects of the SX personal dimension.

It is important to mention works that have analyzed the relationship of IDV and PD cultural dimensions in learning-specific contexts [42,43]. In this way, we can exemplify the impact of this cultural dimension in the SX Learning Environment dimension; HEIs should consider culturally foreign students who, based on their cultural background, prefer to study individually. Certainly, it would be unsatisfying for a student to feel compelled to change their study habits both inside and outside the classroom.

Table 3, built from the empirical analysis of the IDV elements, relates the general norm and family values to the factors that make up the SX dimensions.

4.3. Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Student eXperience

According to Hofstede, the cultural dimension associated with masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) is related to the assertive or modest behavior of a subject. It should be noted that both ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ refer to social roles commonly associated with males and females, respectively. In this way, the masculine is associated with traits commonly observed in males such as assertiveness, competitiveness, and toughness. Regarding the feminine term, it is related to traits commonly observed in females such as caretaking, relationship concerns, and living environment concerns. In this way, and in the words of Hofstede, a society “is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap, both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life” [29].

Individuals identified with a masculine profile tend to seek four goals in organizations: (1) increase their earnings, (2) gain recognition for doing a good job, (3receive a promotion, and (4) have challenging work to do. The fourth goal is associated with the IDV dimension. On the other hand, individuals identified with a female profile tend to seek four goals in organizations: (5) have good relationships with their direct superiors at work, (6) achieve cooperation in the workplace, (7) live in a desirable area with their family, and (8) have the security that they will be able to work for their company for as long as they want. As with the previously mentioned cultural dimensions, masculine and feminine qualities can be observed in the context of organizations and institutions of different kinds. It should be noted that the dimension of masculinity vs. femininity is very controversial, and other cultural models have chosen to use a more politically correct approach. A review of 19 replications of Hofstede’s initial study confirms this [44]. Despite the terminological differences between the various studies that address this dimension, it is possible to observe a strong correlation between these elements with those exposed by Hofstede [45]. We consider it necessary to mention that gender stereotypes may be due to cultural/social norms [46]. Thus, some aspects that vary from one culture to another may be considered uncomfortable or unfair by some people.

Table 4, built from the empirical analysis of the MAS elements, relates the gender and sex values with the factors that make up the SX dimensions.

4.3.1. Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Student eXperience: Social Dimension

The cultural dimension regarding the MAS is directly related to all the factors that make up the social dimension of the SX. That is, community relationships and institutional engagement. This is mainly due to the goals sought by both parts of the MAS spectrum; the relationship with direct superiors (teachers for example) and cooperation in the classroom are easily related to the subject’s predominantly feminine state.

4.3.2. Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Student eXperience: Educational Dimension

Masculinity and femininity are mainly related to two SX dimensions: learning resources/environment and HCI educational/support services. Both, as with the social dimension, are due to the cooperation sought by people with a more feminine than masculine profile.

4.3.3. Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Student eXperience: Personal Dimension

The MAS cultural dimension is related to all the elements of the personal dimension of the SX. This includes the Student Thoughts, Identity, and Background factor, which intrinsically includes the students’ cultural and social background. The student development and outcomes, as a factor of SX, is related to masculine aspects. This is in view of the desire for a challenging educational environment, desire for personal growth, and academic recognition. Students’ emotions are directly related to assertive behavior and/or modest behavior. The relationship with the environment, not necessarily educational, is conditioned to the two behaviors mentioned.

4.4. Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) and Student eXperience

The fourth cultural dimension of Hofstede’s model is related to the uncertainty avoidance (UA) of people in a society. He defines uncertainty avoidance as “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations.” This dimension is related to the feeling of nervous stress, which can be associated with a need for written (and unwritten) rules that reduce ambiguity in a particular context. The Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) provides a value for the degree to which individuals perceive ambiguous or unknown situations. A UAI of 0 is related to the weakest uncertainty avoidance per country, versus 100 for the strongest.

It is important to analyze uncertainty avoidance in relation to students, mainly because this cultural dimension is strongly linked to the feeling of anxiety and stress. This is evidenced by the correlation observed between Lynn’s country anxiety scores and the UAI scores found by Hofstede [29,47]. In addition, it was observed that, in countries with weak UAI, anxiety levels are relatively low. Otherwise, in countries with strong UAI, the level of stress experienced is high, which usually leads to adverse mood states and psychological problems such as anxiety and depression [48].

This cultural dimension transversally affects all the dimensions of the SX, because in any of them the students can feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations. Even so, Hofstede observed certain characteristics of this dimension in the educational environment. Although this was not observed in HEI but in summer schools, it can be extended to this educational level. He observed that students from strong uncertainty avoidance countries expect their professors to be “experts who have all the answers.” A relationship of UA was also observed with the clarity of the teachers when communicating, the approaches when evaluating the students, and the attribution of their own merit by the students. Ultimately, UA is present in all dimensions of the SX.

4.5. Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation (LTO) and Student eXperience

The dimensions defined by Hofstede include some that were not detected in his initial work. An example of this is the Long-Term Orientation (LTO) dimension that originated from the contrast of its cultural dimensions with those obtained after the development of the Chinese Value Survey (CVS) [29]. As a result of the development of the CVS, four dimensions were detected, of which three had a correlative dimension in the proposed Hofstede model. The LTO dimension was included as a fifth cultural dimension by Hofstede, who considered it relevant and not correlating with the uncertainty avoidance dimension. In his formal definition, he said that “long-term orientation stands for the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards in particular, perseverance and thrift. Its opposite pole, short-term orientation, stands for the fostering of virtues related to the past and present respect for tradition, preservation of ‘face’, and fulfilling social obligations”.

The LTO refers, like the aforementioned dimensions, to two opposite value poles. On the one hand we have the values of (1) persistence/perseverance, (2) thrift, (3) ordering relationships by status and observing this order, and (4) having a sense of shame. At the opposite pole we have the values of (5) reciprocation of greetings, favors, and gifts, (6) respect for tradition, (7) protecting one’s “face,” and (8) personal steadiness and stability. The value contrast between the opposite poles of LTO is important. For example, in countries with a low rate of LTO, students attribute their success or failure to luck, while those with a high rate of LTO students attribute success to effort and failure to a lack of it. In addition, talent in mathematics subjects has been associated with students from countries with a high LTO index and a talent for theoretical, abstract sciences in countries with a Short-Term Orientation or low LTO. As a result of points 3–8, the role of the LTO dimension with respect to the social factors of the SX dimensions is evident, both in the social interactions of the social dimension and in the personal dimension. As for points 1 and 2, these can be directly related to educational factors of the SX. For example, tolerance of failure (associated with university dropout), school performance, and self-improvement/enhancement are associated with the value of persistence/perseverance and with the educational engagement of the educational dimension of the SX. Meanwhile, the mere fact of studying, being considered by students as a long- or short-term investment, is associated with the value of thrift.

Table 5, built from the empirical analysis of the LTO elements, relates the general norm and family values with the factors that make up the SX dimensions.

4.6. Indulgence vs. Restraint (IVR) and Student eXperience

Hofstede’s sixth cultural dimension deals with the poles of indulgence versus restraint (IVR). This summarizes the tendency of individuals in a society to have life control, leisure time, and happiness or Subjective Well-Being (SWB). Hofstede defines this dimension as follows: “Indulgence stands for a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun. Its opposite pole, restraint, reflects a conviction that such gratification needs to be curbed and regulated by strict social norms”.

The notable values of this dimension are (1) higher percentages of very happy people in indulgent societies versus lower percentage of very happy people in restraint societies, (2) a perception of personal life control in indulgent societies versus a perception of helplessness in restraint societies, (3) higher importance of leisure in indulgent societies versus lower importance in restraint societies, (4) higher importance of having friends in indulgent societies versus lower importance in restraint societies, (5) more extroverted, optimistic personalities, and positive attitude in indulgent societies versus more neurotic, pessimistic personalities, and cynicism in restraint societies, (6) likelihood to remember positive emotions in indulgent societies versus a lower likelihood in restraint societies, (7) less moral discipline in indulgent societies versus restraint societies, (8) thrift is not very important in indulgent societies versus very important in restraint societies, and (9) indulgent societies are loose, while restraint societies are tight.

The values mentioned in points 1–6 and 8 are clearly associated with the SX personal dimension. This is due to the relationship they have with the personal lives of students, their way of relating beyond the academic field, and leisure activities, while points 7 and 9 are more conditioned to environments. Although these points are related to the personal SX dimension, they can be expanded to the other two dimensions of the SX. The value poles “less moral” and “loose” societies versus “moral” and “tight” societies can be applied to the student–student, student–academician, and student–educational service relationships.

Table 6, built from the empirical analysis of the IVR elements, relates the general norm, personal feelings, and health values with the factors that make up the SX dimensions.

5. Student eXperience Model

The development of a SX model that incorporates cultural aspects consists of a four-stage process: (i) the development of an SLR to know the different definitions of SX, the interest areas, the dimensions/factors/attributes that make up the SX, and the methods used to evaluate the SX; (ii) the identification of factors and dimensions of the national culture in the literature. These elements were contrasted with those found in stage (i), referring to the SX dimensions; (iii) union of the factors and dimensions detected in the literature regarding the SX and the national culture; and (iv) the development of a model with the factors and attributes resulting from the union from stage iii. The model proposed in this stage can be refined based on the results of application of the proposed evaluation methods.

As a result of the fourth stage of the development process, a matrix was formulated that relates cultural and SX factors. This matrix was formulated based on an empirical association between the attributes that Hofstede used to define each cultural dimension and the factors of each dimension of SX [1,29], as can be seen in Section 4. This matrix reveals the SX factors that are involved in each cultural factor within the dimensions of Hofstede’s cultural model. Figure 3 shows, in colored boxes, the cultural dimensions that are affected by certain SX factors. Striped boxes denote cultural dimensions that are not directly affected by factors from the SX dimensions.

The SX–cultural matrix establishes a transversal relationship between cultural aspects and SX at a conceptual level based on empirical information and previously validated models (Figure 3). It indicates that the factors that make up each of the cultural dimensions could have an impact on a certain element within the SX model. In this way, for example, when developing solutions related to the cultural dimension referring to the UA, it must be considered that this will have an impact on all the components of the three SX dimensions. In the same way, when working on solutions related to the PD, it must be taken into consideration that this has implications for elements related to the SX educational dimension, which are related to the perceived quality of the HEIs.

Table 7 presents the SX dimensions’ formalization, detailing cultural aspects to consider in the analysis of the SX factors. For this, cultural factors were added to the description of each SX dimension. The inclusion of cultural factors derives from the SX–cultural dimensions relationship matrix.

Table 7.

SX dimensions including cultural factors.

The proposal can be utilized as a guide to elucidate what solutions should or should not be taken to solve specific problems in the educational field. If we want to implement solutions with a cultural approach, the elements of the SX that will be affected must be considered. Similarly, if we want to work on a specific SX aspect without harming migrants or exchange students, it should be considered what cultural aspects may be affected in the process.

6. Study Limitations

The development of our model considers the undergraduate HEI student as the main study subject. For this reason, any attempt to include subjects belonging to lower grades (e.g., primary or secondary education students) or higher grades (e.g., doctoral students) could lead to unsatisfactory results despite the possibility of them sharing certain needs and characteristics. In the same way, in later stages of our proposal, when we develop the scale and SX evaluation methodology, its validation will be in a specific context. For this reason, we plan to conduct field studies in several cultural contexts.

We must say that it is possible that our own cultural background and gender may have affected our perceptions when developing the model. Obviously, cultural and gender background may unconsciously affect subjects’ perceptions and interactions. In future work, we plan to minimize, or even eliminate, this potential bias by inviting experts of different nationalities, cultures, and genders into the development and validation processes. We will include experts from national contexts other than Ibero-America (Latin America and Spain). This will be essential when incorporating a practical SX evaluation methodology and scale development into our theoretical model.

Regarding the MAS dimension of Hofstede’s model, we should say that the cultural differences of the researchers who have addressed the gender issue have given rise to fierce criticism of the aspects and terms with which Hofstede addresses the female gender and its role in society. Despite the controversy around this dimension, experimental results of other models referring to the same aspects referred to in the MAS dimension show an undeniable correlation with it [44,45]. We decided to use Hofstede’s original dimension as a reference because of its history of practical validation and its correlation with related dimensions of other national culture models.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this article, a theoretical SX model that considers cultural aspects was developed. This model is the result of the relationship between the factors that make up the SX dimensions and the cultural dimensions proposed by Hofstede [4,29]. In consideration of the cultural relationships identified, it is possible to use the SX model to have an idea of the impact that the solutions proposed may have, at a technical level, on the students involved.

With the relationship between the SX and national culture dimensions established, it will be possible to develop solutions for HE students that consider the cultural impact of technical proposals. With the proposed SX model, it would be feasible, for example, to develop tools that allow us to detect users’ problems when interacting with digital systems in consideration of their cultural background [33].

Some possible solutions that can use our model are SX evaluation scales, design guides, or SX evaluation methodologies. It is important to mention that both the SX design and evaluation solutions have a direct impact on students’ well-being and HEIs’ perceived quality. This is due to the detection of failures and management improvements that result from the evaluation of the consumption experiences of the students, thereby improving their satisfaction.

This model is theoretical, as was mentioned in previous sections. This phase of the study deals with the model to know which components of the SX–culture model must be evaluated. Determining how to evaluate those components will be the next step of our work. In the next stage of our proposal, we will develop constructs associated with each dimension/factor, and examine the relationships between constructs, checking our SX model based on a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) [50] and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [51,52]. The model will be further detailed and validated through the development of an SX evaluation methodology and a scale that incorporates items related to cultural aspects. For this, it will be applied practically. This methodology also contemplates the incorporation of cultural aspects in the evaluation methods to be used. Additionally, the emotional and affective aspects will be considered based on previous articles [26]. The evaluation methodology and scale will be carried out with test subjects and experts from different cultures, genders, and nationalities. In this way, we hope to minimize any bias that may be inferred in our study because our cultural or gender background. In addition, we plan to conduct field studies with our model in broader contexts than those it currently covers, i.e., Ibero-America.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., C.R. and F.B.; methodology, N.M., C.R. and F.B.; validation, N.M. and C.R.; formal analysis, N.M. and C.R.; investigation, N.M., C.R. and F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M., C.R. and F.B.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, C.R. and F.B.; project administration, N.M. and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nicolás Matus is a beneficiary of ANID-PFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2023-21230171, and was a beneficiary of the PUCV PhD Scholarship 2022, in Chile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the School of Informatics Engineering of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV) and the Universidad Miguel-Hernández de Elche (UMH).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matus, N.; Rusu, C.; Cano, S. Student eXperience: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Liu, S. Effects of Culture on the Balance Between Mathematics Achievement and Subjective Wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 894774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzherelievskaya, M.A.; Vizgina, A.V. Socio-cultural differences in the self-descriptions of two groups of Azerbaijanian students learning in the Russian and Azerbaijani languages. Psychol. Russ. 2017, 10, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9241-210; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part. 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Wright, P.; Blythe, M.; McCarthy, J. User Experience and the Idea of Design in HCI. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, N.; Roche, G.; Allen, L. Customer Satisfaction. In The Customer Experience Through the Customer’s Eye, 1st ed.; Cogent Publishing: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value with the Customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumer Value; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, S.; Rusu, C.; Matus, N.; Quiñones, D.; Mercado, I. Analyzing the Student eXperience Concept: A Literature Review. In Social Computing and Social Media: Applications in Marketing, Learning, and Health. HCII 2021; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12775. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.; McClelland, R.; Davies, J. The development of a conceptual model of student satisfaction with their experience in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2008, 16, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L.; Knight, P.T. Transforming Higher Education, Society for Research into Higher Education; Open University Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arambewela, R.; Maringe, F. Mind the gap: Staff and postgraduate perceptions of student experience in higher education. High. Educ. Rev. 2012, 44, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, S. Cultural capital and agency: Connecting critique and curriculum in higher education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2011, 32, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, K. Global Perspectives on International Student Experiences in Higher Education: Tensions and Issues, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.T.; Vu, T.P. Mediating transnational spaces: International students and intercultural responsibility. Intercult. Educ. 2017, 28, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.; Baik, C.; Arkoudis, S. Identifying attrition risk based on the first year experience. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornschlegl, M.; Cashman, D. Improving distance student retention through satisfaction and authentic experiences. Int. J. OnlinePedagog. Course Des. (IJOPCD) 2018, 3, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahijan, M.K.; Rezaei, S.; Guptan, V.P. Marketing public and private higher education institutions: A total experiential model of international student’s satisfaction, performance and continues intention. Int. Assoc. Public NonProfit Mark. 2018, 15, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, C. Studies of student life: An overview. Eur. J. Educ. 2004, 39, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, S.A. Mobile learning in the institution of higher learning for Malaysia students: Culture Perspectives. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2011, 1, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, H.; Chavoshi, A. Analysis of the essential factors for the adoption of mobile learning in higher education: A case study of students of the university of technology. Telemat. Inf. 2018, 35, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, P.; Li, Y.; Li, D. Effects of communication style and culture on ability to accept recommendations from robots. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.H. Beyond the Chinese Face: Insights from Psychology. Oxford University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Minkov, M. Long-versus short-term orientation: New perspectives. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, M. What Makes Us Different and Similar: A New Interpretation of the World Values Survey and Other Cross-Cultural Data; Klasika i Stil: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations. Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Culture Connection. Chinese values and the search for culture-free dimensions of culture. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1987, 18, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Beyond Individualism-Collectivism: New Cultural Dimensions of Values. In Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Method, and Application; Kim, U., Triandis, H.C., Kagitcibasi, C., Choi, S.-C., Yoon, G., Eds.; Cross-Cultural Research and Methodology Series; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1994; Volume 18, pp. 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, J.; Rusu, C.; Pow-Sang, J.A.; Roncagliolo, S. A cultural-oriented usability heuristics proposal. In Proceedings of the 2013 Chilean Conference on Human—Computer Interaction, ChileCHI 2013, Temuco, Chile, 11-15 November 2013; ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. 2013; pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, N.; Cano, S.; Rusu, C. Emotions and Student eXperience: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings 2021, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 8–10 September 2021; Volume 3070. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, C.; Cano, S.; Rusu, V.; Matus, N.; Quiñones, D.; Mercado, I. Student eXperience in Times of Crisis: A Chilean Case Study. In Social Computing and Social Media: Applications in Marketing, Learning, and Health. HCII 2021; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12775. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, N.; Ito, A.; Rusu, C. Analyzing the Impact of Culture on Students: Towards a Student eXperience Holistic Model. In Social Computing and Social Media: Applications in Education and Commerce. HCII 2022; Meiselwitz, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13316. [Google Scholar]

- Taras, V.; Rowney, J.; Steel, P. Half a century of measuring culture: Review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawter, L.; Garnjost, P. Cross-Cultural comparison of digital natives in flipped classrooms. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, J.; Zainuddin, Z.; Zulfikar, T.; Lugendo, D.; Zulkarnaini, Y.Y. When online learning and cultural values intersect: Indonesian EFL students’ voices. Issues Educ. Res. 2022, 32, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, J.C.; Murzi, H.; Schuman, A.L. Effects of Uncertainty Avoidance and Country Culture on Perceptions of Power Distance in the Learning Process. In Proceedings of the (2021) ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Online, 26 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya, M. Classroom Interaction Affected by Power Distance. In Language Teaching Methodology and Classroom Research and Research Methods; 2008; Available online: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-artslaw/cels/essays/languageteaching/languageteachingmethodologymichikokasuya.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Alshahrani, A. Power Distance and Individualism-Collectivism in EFL Learning Environment. AWEJ 2017, 8, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, H. Power distance: Implications for English language teaching. Niigata Stud. Foreign Lang. Cult. 2001, 7, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard, M. Book review: Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2001, 1, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.H.; Hofstede, G.; Arrindell, W.A. Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, R.S.; Liben, L.S. Developmental intergroup theory: Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R. Personality and National Character; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R.N.; Mulvogue, M.K.; Thibodeau, M.A.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2022, 26, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-Item Scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G. A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1969, 34, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Toledo, S.; Gavilan, D. Student Experience, Satisfaction and Commitment in Blended Learning: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Mathematics 2023, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hefetz, A.; Liberman, G. Applying structural equation modelling in educational research / La aplicación del modelo de ecuación estructural en las investigaciones educativas. Cult. Y Educ. 2017, 29, 563–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).