Evaluating Post-Pandemic Undergraduate Student Satisfaction with Online Learning in Saudi Arabia: The Significance of Self-Directed Learning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the primary factors that have exerted the greatest influence on students’ levels of satisfaction with online learning post-pandemic, particularly regarding e-learning systems?

- Has the practice of self-directed learning played a role in enhancing students’ satisfaction with online learning?

- To what degree are undergraduate students satisfied with the quality and experience of online learning in the post-pandemic period?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Online Learning

2.2. Online Learning in Saudi Arabia

2.3. Students’ Satisfaction

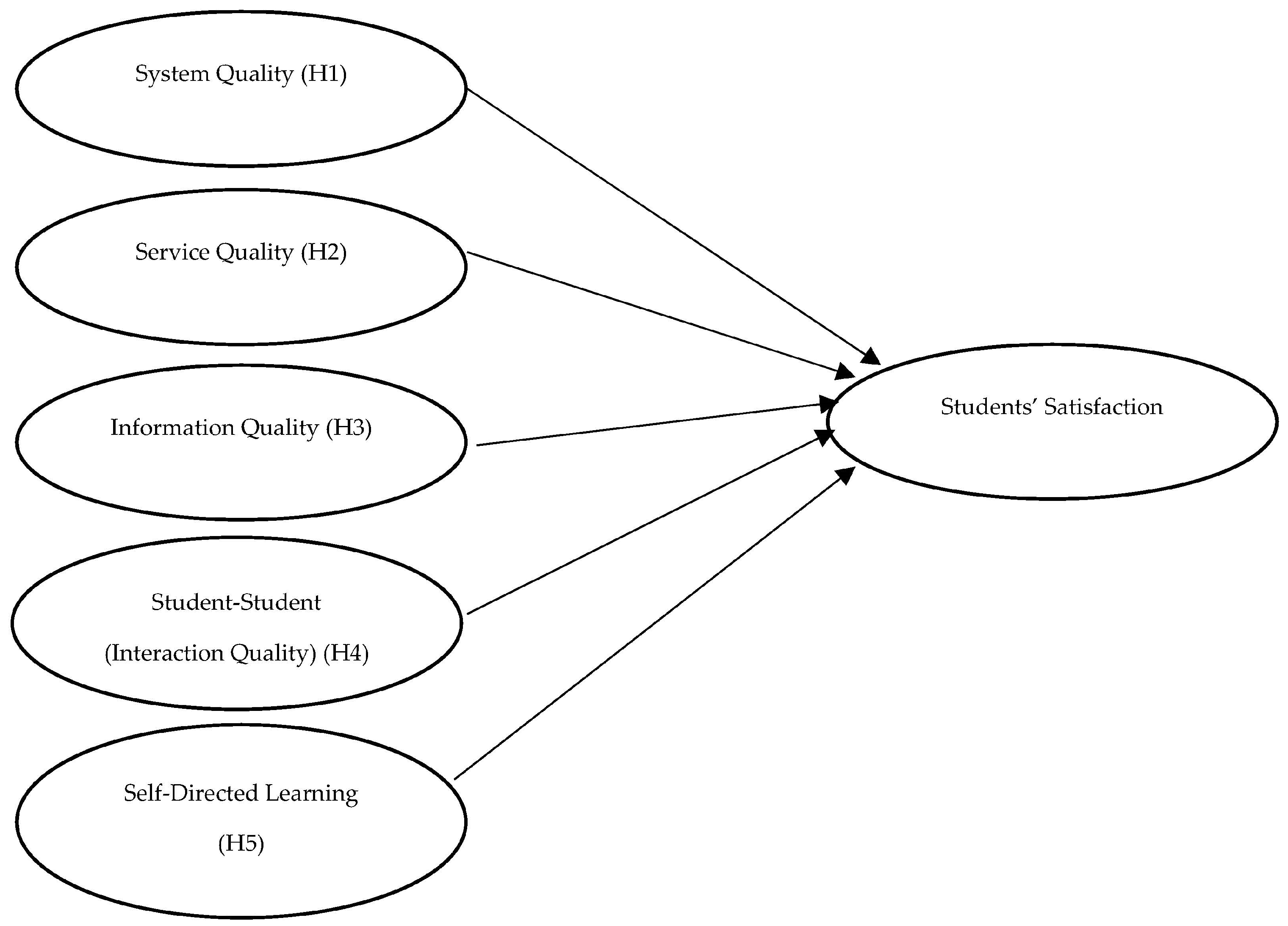

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Hypotheses

3.2.1. System Quality (SysQ)

3.2.2. Service Quality (SerQ)

3.2.3. Information Quality (IQ)

3.2.4. Student–Student Interaction (SST)

3.2.5. Self-Directed Learning (SDL)

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis Procedures

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

8. Limitation and Future Research

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, M.; Jiang, J. COVID-19 and social distancing. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaumik, M.; Hassan, A.; Haq, S. COVID-19 pandemic, outbreak educational sector and students online learning in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alkabaa, A.S. Effectiveness of using E-learning systems during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Experiences and perceptions analysis of engineering students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 10625–10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.K.H.; El-Hassan, W.S.; Al-Ahdal, A.A.M.H.; Hassan, A.A. Distance education in higher education in saudi arabia in the post-covid-19 era. World J. Educ. Technol. Curr. Issues 2021, 13, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajab, K.D. The Effectiveness and Potential of E-Learning in War Zones: An Empirical Comparison of Face-To-Face and Online Education in Saudi Arabia. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 6783–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, T.; Glazkova, I.; Zaborova, E. Quality Issues of Online Distance Learning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2017, 237, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabalee, Y.B.; Santally, M.I. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 2623–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Saxena, C.; Baber, H. Learner-content interaction in e-learning- the moderating role of perceived harm of COVID-19 in assessing the satisfaction of learners. Smart Learn. Environ. 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioni, I.; Xu, W.; Nash, C.; Xue, L. Satisfaction with online education among students, faculty, and parents before and after the COVID-19 outbreak: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1128034. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Alhassan, I.; Binsaif, N.; Alhussain, T. Standard Measuring of E-Learning to Assess the Quality Level of E-Learning Outcomes: Saudi Electronic University Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangaiso, P.; Makudza, F.; Hogo, H. Modelling perceived e-learning service quality, student satisfaction and loyalty. A higher education perspective. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2145805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Nofal, M.; Akram, H.; Albelbisi, N.A.; Al-Okaily, M. Toward a sustainable adoption of E-learning systems: The role of self-directed learning. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidral, W.A.; Oliveira, T.; Di Felice, M.; Aparicio, M. E-learning success determinants: Brazilian empirical study. Comput. Educ. 2018, 122, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtebe, J.S.; Raphael, C. Key factors in learners’ satisfaction with the e-learning system at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D.J. Structural relationship of key factors for student satisfaction and achievement in asynchronous online learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnalı, M. The effect of self-directed learning on the relationship between self-leadership and online learning among university students in Turkey. Tuning J. High. Educ. 2020, 8, 129–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearsley, G.; Lynch, W.; Wizer, D. The Effectiveness and Impact of Online Learning in Graduate Education. Educ. Technol. 1995, 35, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Warschauer, M. Online Learning in Sociocultural Context. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1998, 29, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasim, L. A Framework for Online Learning: The Virtual-U. 1999. Available online: http://www.telelearn.ca (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Online learning and emergency remote teaching: Opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Thurman, A. How Many Ways Can We Define Online Learning? A Systematic Literature Review of Definitions of Online Learning (1988–2018). Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M. A shift from classroom to distance learning: Advantages and Limitations. Int. J. Res. Engl. Educ. 2019, 4, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtain, R. Online Delivery in the Vocational Education and Training Sector: Improving Cost Effectiveness; National Centre for Vocational Education Research: Adelaide, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Al Momani, J.; Alnasraween, M. Perspective Chapter: Online Learning and Future Prospects. In Innovation and Evolution in Tertiary Education [Working Title]; IntechOpen: Houston, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.M.; Khan, M.S.R. E-learning in Saudi Arabia: Past, present and future. Near Middle East. J. Res. Educ. 2014, 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Gamdi, M.A.; Samarji, A. Perceived Barriers towards e-Learning by Faculty Members at a Recently Established University in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2016, 6, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabeeb, A.; Rowley, J. Critical success factors for eLearning in Saudi Arabian universities. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyoob, M. Online learning effectiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Saudi universities. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Shehab, R.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Alrawad, M. Explaining the Factors Affecting Students’ Attitudes to Using Online Learning (Madrasati Platform) during COVID-19. Electronics 2022, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Aldoghan, M.A.; Moustafa, M.A.; Soomro, B.A. Factors affecting online learning, stress and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2023, 16, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. The impact of e-learning quality on student satisfaction and continuance usage intentions during COVID-19. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2021, 11, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Bucarey, C.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller-Pérez, S.; Aguilar-Gallardo, L.; Mora-Moscoso, M.; Vargas, E.C. Student’s satisfaction of the quality of online learning in higher education: An empirical study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsomali, S.; Mandourah, Z.; Almashari, Y.; Alayed, S.; Alqozi, Y.; Alharthi, A. Factors Influencing Satisfaction with Online Learning during COVID-19 Crisis by Undergraduate Medical Students from King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAUHS), Riyadh. Cureus 2023, 15, e41672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldhahi, M.I.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Baattaiah, B.A.; Al-Mohammed, H.I. Exploring the relationship between students’ learning satisfaction and self-efficacy during the emergency transition to remote learning amid the coronavirus pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1323–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, S.; Bahathig, A.; Soliman, M.; Alhassoun, H.; Alkadi, N.; Albarrak, M.; Albadrani, W.; Alghoraiby, R.; Alhaddab, A.; Al-Eyadhy, A. Performance and satisfaction during the E-learning transition in the COVID-19 pandemic among psychiatry course medical students. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawaneh, A.K. The satisfaction level of undergraduate science students towards using e-learning and virtual classes in exceptional condition COVID-19 crisis. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2021, 22, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wei, C.L.; Chen, W.J.; Wang, Y.S. Revisiting the E-Learning Systems Success Model in the Post-COVID-19 Age: The Role of Monitoring Quality. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 5087–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, X. Graduate socialization and anxiety: Insights via hierarchical regression analysis and beyond. Stud. High. Educ. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Gao, Q.; Ge, X.; Lu, J. The relationship between social media and professional learning from the perspective of pre-service teachers: A survey. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 2067–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.D.; Persky, A.M. Developing self-directed learners. Am. Assoc. Coll. Pharm. 2020, 84, 847512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Ouyang, F.; Long, T.; Liu, S. Profiling students’ learning engagement in MOOC discussions to identify learning achievement: An automated configurational approach. Comput. Educ. 2024, 219, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xing, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, L. Exploring the influence of gamified learning on museum visitors’ knowledge and career awareness with a mixed research approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alojail, M.; Alshehri, J.; Khan, S.B. Critical Success Factors and Challenges in Adopting Digital Transformation in the Saudi Ministry of Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jung, E.; Yoon, M.; Chang, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, D.; Demir, F. Exploring the structural relationships between course design factors, learner commitment, self-directed learning, and intentions for further learning in a self-paced MOOC. Comput. Educ. 2021, 166, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussain, T. Evaluating and Measuring the Impact of E-Learning System Adopted in Saudi Electronic University. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahrani, E.M.; Al Naam, Y.A.; AlRabeeah, S.M.; Aldossary, D.N.; Al-Jamea, L.H.; Woodman, A.; Shawaheen, M.; Altiti, O.; Quiambao, J.V.; Arulanantham, Z.J.; et al. E-Learning experience of the medical profession’s college students during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alojail, M.; Alturki, M.; Bhatia Khan, S. An Informed Decision Support Framework from a Strategic Perspective in the Health Sector. Information 2023, 14, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, P.; Khan, S.B.; Kumar, A.; Alojail, M.A.; Rathore, P.S. (Eds.) Internet of Things in Business Transformation: Developing an Engineering and Business Strategy for Industry 5.0; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. In Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Chapter 12; pp. 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Duan, H.; Liu, S.; Mu, R.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z. Improving knowledge gain and emotional experience in online learning with knowledge and emotional scaffolding-based conversational agent. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2024, 27, 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Hu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y. Opinion formation analysis for Expressed and Private Opinions (EPOs) models: Reasoning private opinions from behaviors in group decision-making systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, P.; Guenther, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Zaefarian, G.; Cartwright, S. Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | The Purpose | The Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies on Online Learning in Saudi Arabia Before COVID-19 | |||

| [26] | Investigating the growth of e-learning focuses mainly on the obstacles and future prospects. | Descriptive approach |

|

| [27] | Examining the barriers hindering the adoption of e-learning in higher education. | Quantitative approach (MANCOVA) |

|

| [28] | Providing insights into the critical success factors for e-learning | Qualitative approach |

|

| Studies on Online Learning in Saudi Arabia After COVID-19 | |||

| [29] | Examining undergraduates’ attitudes toward the effectiveness of online learning activities through the Blackboard during COVID-19. | Quantitative approach |

|

| [30] | Examining the attitudes of school students toward online learning during the pandemic with a particular emphasis on the Madrasati platform. | Quantitative approach |

|

| [31] | Examining the effects of various factors—such as time constraints, lack of support, technical difficulties, internet accessibility issues, and insufficient technical skills—on online learning during COVID-19. Furthermore, they investigated the influence of online learning on the stress and anxiety levels of students. | Quantitative approach |

|

| Studies in Students’ Satisfaction with Online learning in Saudi Arabia | |||

| [37] | Exploring the satisfaction of science students with e-learning (asynchronous learning) and virtual classes (synchronous learning) during the COVID-19 crisis, considering demographic variables such as students’ area of specialization, academic level, and GPA. | Quantitative approach (ANOVA) |

|

| [35] | Assessing undergraduate students’ satisfaction with e-learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic and explore the relationship between online learning self-efficacy and satisfaction. | Quantitative approach |

|

| [34] | Examining students’ performance and satisfaction during the pandemic in psychiatry course through conducting a comparative evaluation using pre- and post-pandemic student survey data. | Quantitative approach |

|

| Construct | Items | Adapted from |

|---|---|---|

| System Quality (SysQ) | SysQ1: The E-learning systems used by my university is convenient to use SysQ2: The E-learning systems used by my university enable me to quickly locate the information I need. SysQ3: The E-learning systems used by my university system are well structured SysQ4: The E-learning systems used by my university are easy to use. | [14] |

| Service Quality (SerQ) | SerQ1: The service personnel are always ready to assist anytime I require assistance with the e-learning systems. SerQ2: The service personnel are keen to offer timely services and support regarding e-learning systems. SerQ3: The service personnel are knowledgeable enough to address my issues regarding the E-learning systems. | |

| Information Quality (IQ) | IQ1: Information and course content provided by the E-learning systems are always available during the semester IQ2: Information and course content provided by the E-learning systems are easy to understand IQ3: Information and course content provided by the E-learning systems appear clear and well formatted IQ3: Information and course content provided by the E-learning systems are in a readily usable form | [47] |

| Student–Student Interaction (SSI) | SSI1: The E-learning systems used by my university facilitate easy communication with classmates. SSI2: The E-learning systems used by my university facilitates the efficient and effective sharing of information with my classmates. SSI3: The E-learning systems used by my university allow for convenient storage and sharing of documents with my classmates. SSI4: The E-learning systems used by my university enable me to quickly locate my classmates’ contact information. | [14] |

| Self-Directed Learning (SDL) | SDL1: Regarding my learning and studying style, I can see myself as a self-directed person. That is, I can set my learning goals and organize my learning activities independently without constant guidance and supervision from others. SDL2: I exhibit self-discipline in my studies and find it effortless to allocate time for studying and finishing assignments SDL3: I establish goals for my studies and demonstrate a strong sense of initiative. SDL4: I can properly organize my study schedule and meet deadlines for tasks. | [13] |

| Students Satisfaction (SS) | SS1: Online learning is a wonderful experience. SS2: I am satisfied with the online learning experience. SS3: I would like to study more online courses. | [48] |

| Variable | Items | Indicator Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SysQ | SysQ1 | 0.888 | 0.853 | 0.899 | 0.692 |

| SysQ2 | 0.703 | ||||

| SysQ3 | 0.847 | ||||

| SysQ4 | 0.877 | ||||

| SerQ | SerQ1 | 0.792 | 0.907 | 0.904 | 0.760 |

| SerQ2 | 0.996 | ||||

| SerQ3 | 0.813 | ||||

| IQ | IQ1 | 0.735 | 0.861 | 0.904 | 0.702 |

| IQ2 | 0.884 | ||||

| IQ3 | 0.884 | ||||

| IQ4 | 0.841 | ||||

| SSI | SSI1 | 0.839 | 0.871 | 0.911 | 0.719 |

| SSI2 | 0.888 | ||||

| SSI3 | 0.878 | ||||

| SSI4 | 0.781 | ||||

| SDL | SDL1 | 0.850 | 0.893 | 0.925 | 0.754 |

| SDL2 | 0.887 | ||||

| SDL3 | 0.884 | ||||

| SDL4 | 0.852 | ||||

| SS | SS1 | 0.930 | 0.893 | 0.933 | 0.823 |

| SS2 | 0.946 | ||||

| SS4 | 0.842 |

| Variables | IQ | SDL | SerQ | SSI | SS | SysQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ | 0.838 | |||||

| SDL | 0.325 | 0.868 | ||||

| SerQ | 0.342 | 0.071 | 0.872 | |||

| SSI | 0.500 | 0.334 | 0.352 | 0.848 | ||

| SS | 0.180 | 0.389 | 0.020 | 0.218 | 0.907 | |

| SysQ | 0.572 | 0.318 | 0.346 | 0.631 | 0.276 | 0.832 |

| Variables | IQ | SDL | SerQ | SSI | SS | SysQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ1 | 0.735 | 0.279 | 0.404 | 0.422 | 0.110 | 0.361 |

| IQ2 | 0.884 | 0.316 | 0.286 | 0.400 | 0.179 | 0.499 |

| IQ3 | 0.884 | 0.230 | 0.236 | 0.461 | 0.181 | 0.502 |

| IQ4 | 0.841 | 0.285 | 0.267 | 0.400 | 0.093 | 0.569 |

| SDL1 | 0.378 | 0.850 | −0.006 | 0.340 | 0.413 | 0.336 |

| SDL2 | 0.175 | 0.887 | 0.078 | 0.312 | 0.289 | 0.262 |

| SDL3 | 0.318 | 0.884 | 0.127 | 0.294 | 0.281 | 0.282 |

| SDL4 | 0.224 | 0.852 | 0.074 | 0.203 | 0.330 | 0.204 |

| SS1 | 0.157 | 0.338 | −0.010 | 0.184 | 0.930 | 0.229 |

| SS2 | 0.202 | 0.413 | 0.036 | 0.230 | 0.946 | 0.314 |

| SS3 | 0.115 | 0.288 | 0.026 | 0.170 | 0.842 | 0.188 |

| SSI1 | 0.469 | 0.228 | 0.297 | 0.839 | 0.178 | 0.514 |

| SSI2 | 0.430 | 0.380 | 0.306 | 0.888 | 0.158 | 0.615 |

| SSI3 | 0.419 | 0.312 | 0.304 | 0.878 | 0.236 | 0.541 |

| SSI4 | 0.378 | 0.204 | 0.288 | 0.781 | 0.141 | 0.470 |

| SerQ1 | 0.361 | 0.093 | 0.792 | 0.296 | −0.001 | 0.300 |

| SerQ2 | 0.340 | 0.062 | 0.996 | 0.354 | 0.021 | 0.343 |

| SerQ3 | 0.322 | 0.128 | 0.813 | 0.269 | 0.003 | 0.307 |

| SysQ1 | 0.525 | 0.324 | 0.278 | 0.558 | 0.277 | 0.888 |

| SysQ2 | 0.426 | 0.346 | 0.343 | 0.538 | 0.124 | 0.703 |

| SysQ3 | 0.509 | 0.143 | 0.332 | 0.523 | 0.236 | 0.847 |

| SysQ4 | 0.445 | 0.291 | 0.249 | 0.516 | 0.239 | 0.877 |

| Hypothesis | β | T Statistics | p Values | Confidence Interval | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Level 2.5% | Upper Level 97.5% | |||||

| (IQ) → (SS) | −0.028 | 0.257 | 0.797 | −0.225 | 0.218 | Not supported |

| (SDL) → (SS) | 0.333 | 4.509 | 0.000 | 0.185 | 0.476 | Supported |

| (SerQ) → (SS) | −0.069 | 0.736 | 0.462 | −0.266 | 0.084 | Not supported |

| (SSI) → (SS) | 0.020 | 0.202 | 0.840 | −0.181 | 0.222 | Not supported |

| (SysQ) → (SS) | 0.198 | 1.531 | 0.126 | −0.072 | 0.427 | Not supported |

| Study | Country | Sample Size | System Quality | Service Quality | Information Quality | Student–Student Interaction | Self-Directed Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Study | Saudi Arabia | 150 | Not Significant | Not Significant | Not Significant | Not Significant | Significant |

| Cidral et al. (2018) [14] | Brazil | 301 | Significant | Not Significant | Significant | Significant | Not Studied |

| Dangaiso et al. (2022) [12] | Zimbabwe | 321 | Significant | Significant | Significant | Not Studied | Not Studied |

| Al-Adwan et al. (2022) [13] | Jordan | 590 | Significant | Significant | Significant | Not Studied | Not Significant |

| Jiménez-Bucarey et al. (2021) [33] | Peru | 1430 | Significant | Significant | Not Studied | Not Studied | Not Studied |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshathry, S.; Alojail, M. Evaluating Post-Pandemic Undergraduate Student Satisfaction with Online Learning in Saudi Arabia: The Significance of Self-Directed Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198889

Alshathry S, Alojail M. Evaluating Post-Pandemic Undergraduate Student Satisfaction with Online Learning in Saudi Arabia: The Significance of Self-Directed Learning. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(19):8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198889

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshathry, Sahar, and Mohammed Alojail. 2024. "Evaluating Post-Pandemic Undergraduate Student Satisfaction with Online Learning in Saudi Arabia: The Significance of Self-Directed Learning" Applied Sciences 14, no. 19: 8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198889

APA StyleAlshathry, S., & Alojail, M. (2024). Evaluating Post-Pandemic Undergraduate Student Satisfaction with Online Learning in Saudi Arabia: The Significance of Self-Directed Learning. Applied Sciences, 14(19), 8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198889