Abstract

Background: The appropriate choice of footwear is crucial for foot health, yet its impact on different populations and medical conditions remains understudied. This review explores the effect of shoe fit on the prevention of podiatric disorders and overall well-being. Methods: The research included major academic databases such as MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and PEDro, using specific keywords. A scoping review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, encompassing studies on shoe fit across diverse populations and conditions. Medical databases and grey literature were also included. Results: Five studies were included, covering topics such as footwear advice for women over 50, the effect of shoes in preventing calluses under the metatarsals, the effectiveness of a shoe-related intervention for gout patients, and the impact of custom-fitted shoes on physical activity in children with Down syndrome. Results showed that well-fitting shoes can prevent callus formation, but the efficacy of custom-fitted shoes for increasing physical activity requires further research. Conclusions: The choice of appropriate footwear should not be solely based on aesthetic considerations but rather on the specific needs of each individual. Physicians should consider providing advice on appropriate shoe characteristics as a primary intervention

1. Introduction

Foot health is crucial for overall well-being, as it directly impacts mobility, balance, and the ability to perform daily activities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Poor foot health can lead to pain, disability, and a decreased quality of life. Footwear plays a fundamental role in preventing these issues, as well as in enhancing physical activity and managing existing conditions, especially in specific populations like the elderly, athletes, and individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes. For example, improper shoe fit in diabetic patients can lead to serious complications like foot ulcers. Therefore, the selection of appropriate footwear should not be limited to aesthetic considerations but should address the specific needs of each individual.

Recent studies have explored various aspects of shoe fit, such as size, width, and customization, and their impact on different demographic groups, including elderly women, individuals with gout, children and adolescents with Down syndrome, and young athletes [2,3,7,8,9,10,11]. These studies aimed to fully examine the effects of footwear on key parameters like pain, disability, physical activity, ulcer prevention, gait, and posture [7,12,13]. Additionally, research shows that shoe fit can influence postural control—the body’s ability to maintain balance and stability while standing or moving—and proprioception, which is the body’s sense of its position and movement in space [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These aspects are essential for maintaining foot health and overall physical function [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

In this review, we adopted a scoping review methodology, which is a type of research synthesis that maps the existing literature on a specific topic, identifies key concepts, theories, sources of evidence, and highlights research gaps. This approach is particularly useful when the evidence is diverse and dispersed, as it allows for a broad and inclusive exploration without the restrictive criteria of a systematic review. We selected this methodology to thoroughly explore the impact of shoe fit across diverse populations and conditions, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the topic. The guidelines for this scoping review were based on the frameworks provided by Pollock et al. (2021) [32] and Peters et al. (2020) [33], ensuring a rigorous and transparent process.

To provide a more holistic overview, the review also integrated recent studies focusing on athletes and individuals with specific medical conditions like diabetes, where improper shoe fit can have severe consequences. Furthermore, we included research on the biomechanical impact of shoe fit, examining how it influences gait and posture, and consequently, foot health and overall well-being [34,35]. Different types of footwear, such as high heels, flats, and athletic shoes, were also considered, given their varying effects on foot health. Additionally, emerging technologies, such as machine learning applications in shoe design and foot health prediction, were explored to highlight future directions for personalized footwear solutions.

The objective of this review was to provide practical, evidence-based recommendations for footwear selection that cater to the diverse needs of individuals while identifying areas for future research to advance the understanding of how footwear affects health [6,36,37,38,39].

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the methodology of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The JBI methodology provides a comprehensive framework for conducting systematic and scoping reviews, including detailed guidance on searching, selecting, appraising, and synthesizing evidence. The methodology used in this review followed the guidelines provided by Pollock et al. [32] and Peters et al. [33] to ensure rigor and transparency.

An initial limited search was performed on MEDLINE through the PubMed interface to identify relevant keywords and concepts related to shoe fit and foot health. This preliminary search informed the development of a comprehensive search strategy. The following databases were systematically searched: MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Additionally, grey literature sources were included, such as Google Scholar and direct consultations with field experts.

The specific search terms used included combinations of the following keywords: “shoe fit”, “foot health”, “footwear”, “podiatry”, “custom footwear”, “diabetes”, “athletes”, “foot ulcers”, “biomechanics”, “gait”, and “posture”. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine these terms and refine the search results.

The search results were as follows:

- MEDLINE: 46 records retrieved

- Scopus: 74 records retrieved

- PEDro: 2 records retrieved

- Cochrane Central: 0 records retrieved

In total, 122 records were identified across these databases. After removing 35 duplicates, 87 unique records remained for screening. The study selection involved a two-stage process: first, a review of titles and abstracts, and second, a full-text assessment. The inclusion criteria focused on studies that addressed the impact of shoe fit on foot health across diverse populations, including individuals with specific conditions like diabetes or Down syndrome, as well as athletes.

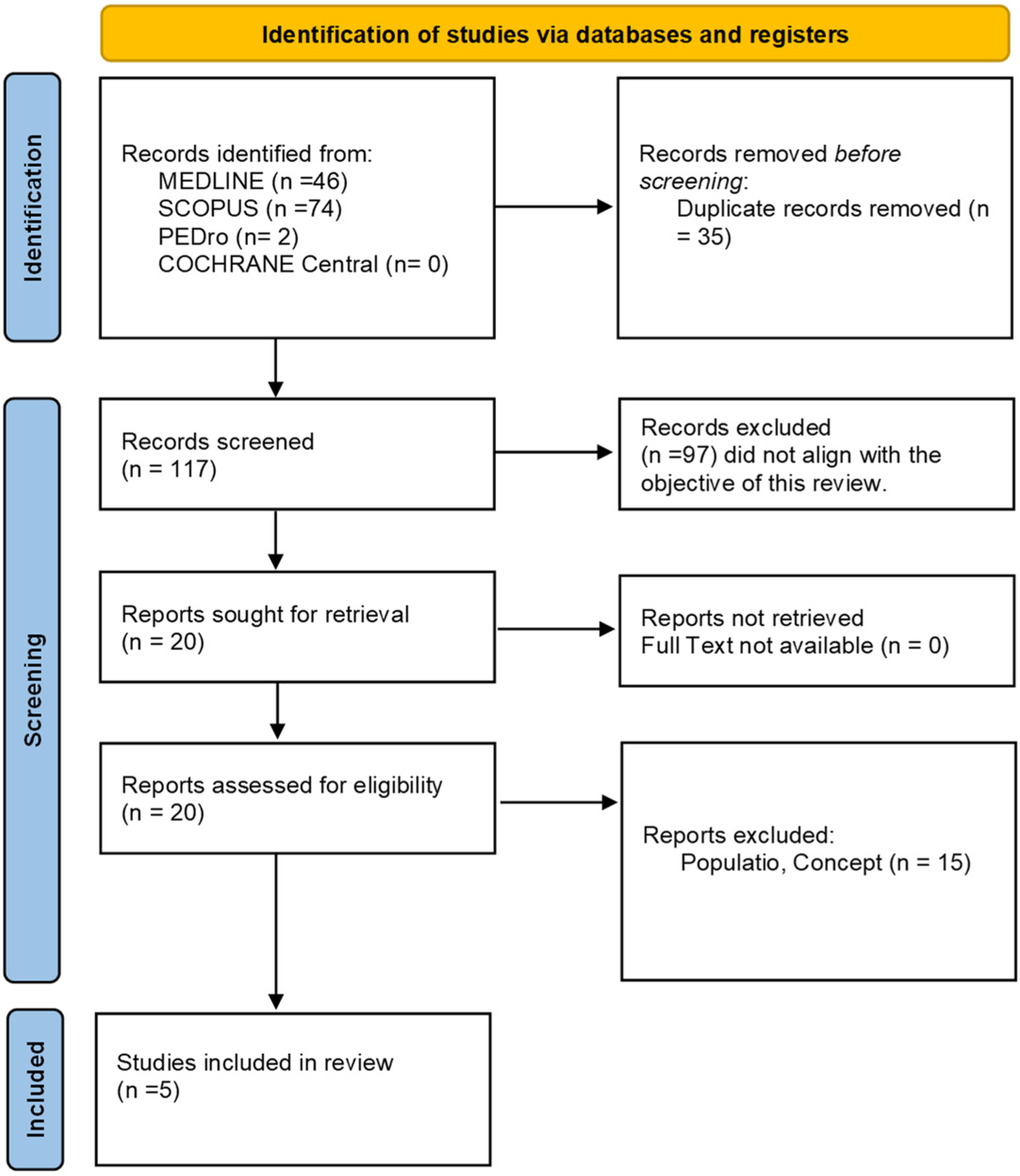

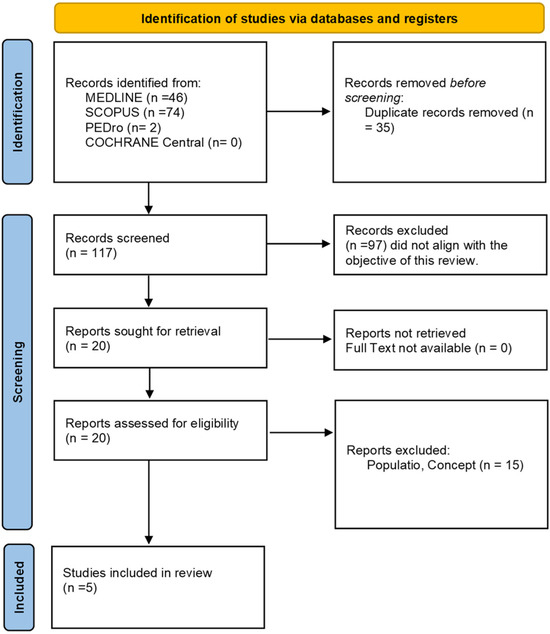

For transparency, a PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) flow diagram was used to illustrate the study selection process [32,33,40].

2.1. Research Question

The broad objective of this scoping review was to examine in detail the available evidence on the impact of shoe fit on foot health and overall well-being, with the aim of providing practical recommendations for footwear selection. The research question guiding this review was: “What is the current state of evidence regarding the impact of shoe fit and choice on foot health and well-being across diverse populations, including both healthy individuals and those with specific medical or foot conditions?”.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) criteria:

Population (P): The population targeted in the included studies encompassed individuals of any age and health status, including both healthy individuals and those with specific medical conditions. Specifically:

- General populations: Healthy individuals, including men and women across different age groups.

- Specific conditions: Individuals with medical conditions relevant to foot health, such as:

- Diabetes: At risk of developing plantar ulcers.

- Gout: Experiencing foot pain and functional limitations.

- Down syndrome: Where podiatric deformities and limited physical activity can be impacted by footwear.

- Elderly individuals: Particularly vulnerable to issues caused by inadequate footwear, such as foot pain and difficulties in walking.

Concept (C): The key concept of interest was shoe fit, which included various factors such as shoe size, width, support, and comfort, as well as the adaptability of shoes to the specific needs of the individual. The studies examined different aspects of footwear:

- Shoe size: The appropriateness of shoe size in fitting the individual’s foot.

- Shoe width and fit: The width of the shoes and how well they match the foot’s shape.

- Support: The level of support provided by the shoes in preventing foot problems (e.g., calluses, ulcers, deformities).

- Comfort: The individual’s perceived comfort, which is crucial for preventing chronic pain and injuries.

- Educational interventions: The use of informational materials or educational programs to raise awareness among individuals and healthcare professionals about the importance of proper footwear.

- Custom-made shoes: The effects of custom-fitted shoes for individuals with specific needs, such as children with Down syndrome or people with gout.

Context (C): The context in which the studies were conducted varied widely, encompassing clinical as well as community settings. The studies covered different scenarios where footwear choice plays an important role:

- Clinical settings: Medical or hospital environments, such as diabetic care units or podiatry clinics, where the focus is on preventing and managing foot problems.

- Community settings: Studies conducted in community or home environments, where the impact of footwear choice is assessed in daily life, particularly for elderly individuals or those with limited mobility.

- Sport and recreational settings: Studies exploring the use of footwear during physical or sports activities, focusing on injury prevention due to inappropriate footwear.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not meet specific PCC criteria were excluded.

2.4. Search Strategy

An initial limited search on MEDLINE was conducted through the PubMed interface to identify relevant articles. This initial search helped to develop a comprehensive search strategy for MEDLINE. Following this, a thorough search was conducted across several databases, including MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Additionally, grey literature sources were searched, including Google Scholar and direct contacts with experts in the field. Grey literature refers to research that is either unpublished or has been published in non-commercial forms, such as theses, dissertations, conference proceedings, and reports from government agencies. The searches were conducted on 23 June 2024, with no date limitations. The rationale for not including CINAHL was based on the focus and relevance of the selected databases to the specific research questions of this review.

2.5. Study Selection

The study selection process was systematic and involved refining search results using the document management program ZOTERO for duplicate removal. The selection process occurred in two stages: an initial review of titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text assessment. These stages were conducted independently by two experts in the field of podiatry and footwear research, with a third expert, specialized in systematic review methodology, stepping in to resolve discrepancies such as differences in the selection of full-text articles for review. It is important to note that studies selected for the review were not critically appraised, as per the standard protocol for scoping reviews (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of included studies.

2.5.1. Study Quality Assessment or Risk of Bias Assessment

To assess the quality and risk of bias of the included studies, the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool was utilized for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), while the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied to observational studies. The RoB 2 tool evaluated RCTs based on several criteria, including the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall risk of bias (Table 3). For observational studies, the NOS assessed the selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure/outcome, providing an overall quality rating for each study (Table 4).

Table 3.

RCT risk of bias assessment (RoB 2).

Table 4.

Observational studies: quality assessment (Newcastle–Ottawa scale).

2.5.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

In the data extraction and synthesis phase, relevant data were extracted from the included articles based on predefined criteria, including information on participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study conclusions. Specific data related to shoe fit, choice, and conditions were categorized into these broader criteria. For example, data on well-being and disorders were included under outcomes, while specific shoe fit interventions were classified under interventions. A qualitative synthesis was performed to integrate this information, focusing on how it addressed the primary research question. The analysis approach involved thematic synthesis, where key themes and patterns were identified across the studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of shoe fit on foot health and overall well-being. During the study selection process, discrepancies between the two reviewers were defined as disagreements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of a study based on the eligibility criteria. These discrepancies could arise from differences in interpretation of the study’s population, intervention, outcome measures, or relevance to the research question. When a disagreement occurred, the two reviewers first discussed their perspectives in detail to reach a consensus. If consensus could not be achieved, a third expert reviewer, who was not involved in the initial review process, was consulted to make the final decision. This third reviewer provided an independent evaluation without participating in prior discussions to minimize bias.

All discrepancies, including the criteria and rationale for each decision, were documented systematically. This documentation ensured transparency and consistency throughout the study selection process, allowing for a clear record of how each disagreement was resolved.

3. Results

The flowchart of article selection is presented in Figure 1. A total of 152 records were initially identified through bibliographic searches across different databases: MEDLINE (46 records), Scopus (74 records), PEDro (2 records), and grey literature. After removing 35 duplicates, 117 records remained. Of these, 117 were screened based on titles and abstracts, and 97 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria or because they did not align with the objective of this review. The full texts of 20 reports were assessed for eligibility, and 15 were excluded due to reasons such as irrelevant population and concept. Five studies were finally included in the review (Table 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses 2020 (PRISMA) flow-diagram.

3.1. Study Designs and Interventions

Of the five studies included:

- Three were randomized controlled trials (RCTs):

- ○

- Van der Zwaard et al. (2014) [3] developed and evaluated an information brochure for GPs on shoe advice.

- ○

- Frecklington et al. (2019) [8] investigated the effectiveness of a shoe-related intervention for gout patients.

- ○

- Hassan et al. (2021) [9] assessed the feasibility of custom-made shoes for increasing physical activity in children with Down syndrome.

- Two were observational studies:

- ○

- Kase et al. (2018) [7] examined the effect of proper shoe size and width on callus formation.

- ○

- Van der Zwaard et al. (2014) [3] compared podiatric treatment with standardized shoe advice in elderly women with forefoot pain.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of five studies were included in this review. These studies varied in design, population, and intervention focus:

- Study Designs: three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and two observational studies.

- Population: The populations studied included elderly women, individuals with gout, children and adolescents with Down syndrome, and healthy young women.

- Interventions: The interventions focused on shoe fit characteristics, including shoe width, size, and custom-made shoes.

3.3. Impact of Proper Shoe Fit on Foot Health

Studies consistently demonstrated that appropriate shoe fit can significantly improve foot health outcomes:

- Pain Reduction: Van der Zwaard et al. (2014) [3] showed that educational materials promoting shoe advice led to a significant reduction in foot pain among elderly women.

- Ulcer Prevention: Kase et al. (2018) [7] found that properly sized shoes reduced pressure and shear stresses under the metatarsal heads, preventing callus formation and potential ulcers.

3.4. Effects of Custom-Made Footwear

Custom-made footwear was examined in two studies:

- In Children with Down Syndrome: Hassan et al. (2021) [9] observed a positive trend in physical activity levels among children with Down syndrome who used custom-made shoes, although further research is needed for conclusive results.

- In Individuals with Gout: Frecklington et al. (2019) [8] found that specialized shoes improved overall foot comfort, but the impact on pain levels was minimal.

3.5. Role of Educational Interventions

Educational materials and interventions played a significant role in improving shoe choices and outcomes:

- Educational Brochures: Van der Zwaard et al. (2014) [3] demonstrated that providing educational brochures to primary care physicians resulted in higher-quality shoe choices among elderly women.

3.6. Preventive Potential of Footwear Interventions

The studies highlighted the importance of preventive footwear strategies:

- Callus Formation: Kase et al. [7] highlighted that shoes properly fitted for width and size are effective at reducing the formation of calluses, especially under the metatarsal heads.

- Diabetic Foot Complications: The review emphasized the need for further studies on diabetic populations, focusing on footwear interventions that prevent foot ulcers.

3.6.1. The Suitability and Importance of Footwear

Van der Zwaard BC., 2014 [3]: This study developed an information brochure for general practitioners (GPs) regarding the importance of providing advice on wearing good-quality and well-fitting shoes. Following a review of the literature on the impact of shoe characteristics on foot pathologies and kinematics, an information brochure was created. The impact of the brochure on shoe selection was evaluated in a randomized controlled design involving 70 women without a history of diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, or identified foot problems in the last year. Both groups were asked to go to a store and select shoes that were aesthetically pleasing and considered appropriate for standing and walking for long periods. The intervention group was given the pamphlet and the content was explained to them. Women who used the brochure chose higher-quality shoes compared to those in the control group.

Van der Zwaard BC., 2014 [3]: This study examined the effect of podiatric treatment versus standard advice on appropriate shoe characteristics and shoe fitting for individuals aged 50 and older with forefoot pain in primary care. The study involved 205 participants who were randomly allocated to receive shoe advice guided by an informational leaflet from their GP or be referred for podiatry care. The results showed no significant differences in foot pain and foot function between the two groups, suggesting that primary care physicians should consider providing shoe advice as a first step before referring patients to a podiatrist.

3.6.2. The Effectiveness of Shoe-Related Interventions

Frecklington M., 2019 [8]:This study examined the effectiveness of a shoe-related intervention in treating foot pain and disability in gout patients. The participants, who were randomly assigned to two groups, received standardized podiatric care including palliative nail and skin care, shoe advice, and gout education. The intervention group additionally received a pair of ASICS Cardio Zip 3 shoes tailored to their size and foot for daily use. Measurements were taken at the study’s start, 2, 4, and 6 months. While no significant difference in foot pain was observed between the control and intervention groups, short-term improvements in overall pain, foot impairment/disability, and shoe comfort and fit were noted in the intervention group.

Hassan NM., 2021 [9]: This study aimed to determine the feasibility of conducting a definitive randomized trial to assess the effectiveness of custom-made shoes in increasing physical activity in children and adolescents with Down syndrome. In a double-blind randomized pilot study, 33 participants were divided into two groups: one receiving custom-made shoes from Clarks® and the other on a waiting list. Various feasibility domains were assessed, including recruitment, implementation, acceptability, practicability, limited effectiveness testing, and adaptation. Positive trends favoring custom-made shoes in increasing physical activity were observed, although issues related to co-interventions and shoe fit need to be considered before conducting a definitive study.

3.6.3. Prevention of Foot Problems Through Proper Shoe Fit

Kase R., 2018 [7]: This study investigated whether wearing properly sized and width-fitted shoes (as compared to shoes 1 or 2 cm larger) could prevent callus formation under the second and fifth metatarsals. The study used a snowball sample of 49 healthy women without diabetes. Results showed that wearing properly sized shoes could help prevent callus formation by reducing pressure and shear stress under the second metatarsal and maximum shear stress under the fifth metatarsal.

3.6.4. Summary of Included Sample Characteristics

- Total Sample Size and Range: The included studies had a total sample size of 285 participants, with individual study sample sizes ranging from 33 to 105 participants.

- Gender and Mean Age: The studies included a mix of genders. The mean age of participants ranged from 9.7 years (children with Down syndrome) to 69 years (elderly women).

- Specific Medical Conditions or Special Populations: The studies focused on various populations, including elderly women, individuals with gout, children and adolescents with Down syndrome, and healthy young women.

- Year Range of Studies: The studies reviewed were published between 2014 and 2021.

- Countries of Origin: The studies were conducted in different countries, including The Netherlands, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia.

This table evaluates the risk of bias for the three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in the review. Each study was assessed based on six criteria from the Cochrane RoB 2 tool: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall risk of bias.

This table assesses the quality of two observational studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). The studies were evaluated across three main domains: selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure/outcome. The overall quality rating reflects the cumulative assessment of these criteria.

4. Discussion

Recent studies have extensively explored various aspects of shoe fit, including size, width, and customization, and their impact on different demographic groups such as women over 50 [2,7,8,9,41,42,43,44], individuals with gout, children and adolescents with Down syndrome, as well as young healthy women. These studies aimed to thoroughly evaluate the effects of shoe fit on key parameters such as pain, disability, physical activity, and ulcer prevention. Despite varying study conditions [9,45,46] and contexts, a common and critically important element emerges: the choice of appropriate footwear should not be limited to aesthetic considerations but should instead take into account the specific needs of each individual [12,47]. This scoping review aimed to examine in detail the available evidence on the impact of shoe fit on foot health and overall well-being and provide practical recommendations for footwear selection. Our findings indicate that well-fitted shoes can significantly influence foot health outcomes, especially in specific populations such as the elderly, individuals with gout, and children with Down syndrome. One key finding from Van der Zwaard’s studies is the importance of providing educational materials to guide proper shoe selection. The development and use of an information brochure for GPs were shown to positively influence the shoe choices of women over 50, encouraging them to select higher-quality and better-fitting shoes. This suggests that primary care providers can play a crucial role in promoting foot health by offering basic shoe advice and educational materials. In another study by Van der Zwaard [2], it was demonstrated that shoe advice provided by primary care physicians can be as effective as podiatric treatment in managing non-traumatic forefoot pain in older adults. This finding highlights the potential for integrating footwear advice into routine primary care practices, which could reduce the need for specialist referrals and improve accessibility to foot health interventions. The study by Kase et al. [7] emphasized the preventive [7,48] potential of properly sized and width-fitted shoes on reducing callus formation and associated pressure and shear stress on the metatarsal. These findings underline the importance of ensuring that footwear fits correctly to prevent common foot problems, particularly in populations at risk of pressure-related foot conditions. Frecklington et al. [8] explored the effectiveness of a shoe-related intervention in treating foot pain and disability in gout patients. Although the addition of specialized shoes did not significantly reduce foot pain, it did result in short-term improvements in overall pain, foot disability, and shoe comfort and fit. These results suggest that while specialized footwear may not always address pain directly, it can enhance overall foot comfort and functionality, which are important aspects of managing chronic foot conditions. Hassan et al.‘s [9] study on custom-made shoes for children and adolescents with Down syndrome showed positive trends in increasing physical activity, although the results were not conclusive due to feasibility issues and the need for further research. This highlights the potential benefits of custom footwear in specific populations with unique foot shapes and needs, advocating for more tailored interventions in pediatric care. Based on these findings, the following practical recommendations for footwear selection can be made:

Use of Information Brochures: Providing educational materials to guide individuals in selecting high-quality and well-fitting shoes can positively influence their choices, especially among older adults and those without immediate access to podiatric care. Primary Care Shoe Advice: Primary care physicians should consider offering initial advice on appropriate shoe characteristics and fitting as a first step before referring patients to specialized podiatric care. Custom-Made Shoes for Special Populations: Custom-made shoes may be beneficial for specific populations, such as children with Down syndrome, to increase physical activity and accommodate unique foot shapes. Proper Shoe Size and Width: Ensuring that shoes are properly sized and fitted in width is crucial for preventing callus formation and other foot problems, particularly in populations at risk for pressure-related foot conditions. Explain how the results from Van der Zwaard et al. (2014) [3] indicate that simple educational interventions (e.g., brochures) provided by primary care physicians can lead to improved shoe choices, which, in turn, reduce foot pain. This highlights the potential for incorporating basic foot health education into routine primary care practices to enhance foot health outcomes. Discuss Hassan et al. (2021)’s [9] findings on custom-made shoes. Although the study showed positive trends, the need for more robust evidence underscores the importance of developing targeted interventions that consider the unique foot morphology of children with Down syndrome. This can inform policy on funding and access to custom-made shoes in pediatric care.

Although this review confirms the well-documented benefits of appropriate shoe fit in preventing podiatric issues and enhancing overall well-being, it also identifies a gap in the current literature regarding innovative interventions. Emerging trends in footwear technology, such as the development of smart footwear integrated with sensors for real-time gait and pressure analysis, show promise in advancing individualized treatment plans. Additionally, the use of 3D foot scanning and custom orthotic fabrication using additive manufacturing (3D printing) offers a more precise approach to managing foot deformities and optimizing biomechanical alignment. These innovations could be integrated into routine clinical practice to provide tailored interventions based on real-time biomechanical data, potentially reducing the risk of chronic conditions like plantar fasciitis, hallux valgus, or diabetic foot ulcers.

Moreover, interdisciplinary collaborations between podiatrists, engineers, and digital health experts could lead to the development of novel educational tools and interventions. For example, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to predict foot health outcomes based on gait patterns, or developing apps that guide patients through proper shoe selection and monitoring of foot health metrics. Such innovations would not only enhance clinical outcomes but also empower patients to actively participate in their foot health management. Future research should prioritize clinical trials assessing the efficacy of these technologies to establish evidence-based guidelines for their integration into standard podiatric care. The synthesis of the included studies primarily utilized thematic analysis, which, while foundational, may not have captured the full complexity and nuances of the existing body of research on footwear and foot health. To elevate the rigor and clinical relevance of this review, it was essential to implement a more advanced synthesis method. An in-depth exploration of emerging patterns, such as variations in intervention effectiveness based on biomechanical markers, demographics (e.g., age, gender), or specific pathologies (e.g., diabetic foot vs. rheumatoid arthritis), could elucidate critical variables influencing outcomes.

Furthermore, identifying and critically evaluating contradictions across studies—such as disparities in reported efficacy of custom-fitted shoes or inconsistencies in the impact of educational interventions—can provide a more nuanced interpretation of the findings. This approach would also allow the manuscript to explore potential confounders, such as differences in methodological quality or population characteristics, that may account for these discrepancies.

A comprehensive identification of research gaps was equally important. Highlighting the scarcity of high-quality, multi-center RCTs that investigate long-term outcomes or the limited application of advanced technologies (e.g., digital foot scanning, pressure-mapping sensors) in clinical studies would not only enrich the current analysis but also provide a clear direction for future research priorities. Incorporating these deeper levels of synthesis would substantially enhance the value and applicability of the review’s conclusions, providing a more robust evidence base to inform clinical practice and policy.

In individuals with Down syndrome, custom-made shoes can accommodate unique foot morphology, which is often characterized by flat feet, hypermobility, and altered biomechanics. These shoes can enhance stability and improve overall gait mechanics, potentially increasing physical activity levels and reducing the risk of secondary musculoskeletal issues. However, it is essential to recognize the limitations, such as the potential cost and the need for frequent adjustments as children grow. Moreover, while custom-made shoes have shown promise in improving functionality, long-term studies are needed to validate their effectiveness in preventing orthopedic deformities and promoting long-term physical activity in this population.

For patients with gout, custom-made shoes can provide critical support by redistributing pressure and reducing joint stress, particularly in the metatarsophalangeal joints, which are frequently affected in gouty arthritis. These shoes may help to alleviate pain, improve mobility, and prevent future flare-ups. However, the effectiveness of custom footwear in managing gout remains underexplored, and there are challenges, such as adherence to wearing the shoes and ensuring proper fit over time as the disease progresses. Moreover, more research is required to assess whether these interventions can significantly reduce disability or improve quality of life compared to off-the-shelf options or standard care.

A more detailed investigation into the efficacy and limitations of custom-made shoes would provide clinicians with clearer guidelines on when and how to utilize this intervention, particularly for populations with specific orthopedic or biomechanical challenges. This would also help to delineate the conditions under which custom footwear is most beneficial and cost-effective. Highlight that providing footwear advice during regular check-ups could be an effective strategy for preventing foot problems, particularly in older adults and those with chronic conditions like diabetes. Recommend the integration of custom-made footwear options into healthcare plans for patients with specific needs (e.g., individuals with Down syndrome or those with chronic gout). Suggest that healthcare providers receive training on assessing shoe fit and prescribing appropriate footwear.

This scoping review has several important limitations. Firstly, the number of included studies was limited to five. While the aim of a scoping review was not to generalize the findings but to determine the state of the science or what is known on a subject, the limited number of studies may still restrict the breadth of the conclusions that can be drawn. Furthermore, the methodological quality of the included studies was not critically appraised, which is a common practice in scoping reviews. This lack of critical appraisal means that the reliability of the results may vary, and caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings. Advocate for policies that facilitate access to custom-made footwear for vulnerable populations, such as insurance coverage for therapeutic shoes for diabetic patients or children with congenital conditions. Recommend government-funded programs to educate the public on proper shoe fit, emphasizing the link between footwear and long-term foot health. This could include collaborations with footwear manufacturers to develop affordable and supportive shoe options. Stress the necessity of more high-quality, multi-center RCTs to explore the long-term impact of pressure-relief shoes on preventing diabetic ulcers. Encourage studies that combine biomechanical analysis with emerging technologies like AI and in-shoe sensors to optimize shoe fit and predict foot health outcomes.

5. Clinical Implications

The findings of this scoping review highlight the critical role that proper footwear plays in foot health, especially for populations at higher risk of podiatric issues such as the elderly, individuals with gout, and children with Down syndrome. Primary care physicians and specialists can use these insights to guide clinical practice by offering more proactive advice on footwear selection. The use of educational materials, such as brochures for patients, could significantly improve patient outcomes by helping them choose well-fitted shoes, thereby preventing common foot issues like calluses and pressure-related injuries. Additionally, the introduction of custom-made footwear for specific populations, such as those with unique foot shapes or mobility limitations, can further enhance mobility and comfort, reducing the likelihood of disability. Early intervention through shoe advice in primary care settings can also help reduce the need for more specialized podiatric treatment, making foot health management more accessible and cost-effective. Although the review presents practical recommendations for appropriate footwear and interventions, these guidelines are generalized and lack the precision necessary for clinical application across diverse populations. To increase the clinical utility and impact of the review, it is essential to provide more specific, evidence-based recommendations tailored to distinct demographic and clinical groups.

For example, in elderly populations at risk of falls, clinical guidelines should emphasize footwear with anti-slip soles, firm heel counters, and adequate cushioning to improve stability and reduce fall risk. Recommendations should also incorporate evidence on shoe fastening mechanisms (e.g., Velcro or elastic laces) that facilitate ease of use for individuals with limited dexterity or mobility impairments.

For patients with diabetes, detailed guidance should focus on selecting footwear that incorporates offloading features, such as insoles designed to reduce plantar pressure and mitigate ulcer risk. The use of therapeutic footwear that adapts to pressure patterns, monitored through advanced in-shoe pressure-mapping technologies, should be integrated as part of a proactive diabetic foot management program. Such technology-enhanced monitoring systems can provide real-time feedback and allow for personalized modifications to optimize foot protection.

In the context of athletic populations or individuals engaged in high-impact activities, recommendations should specify footwear with tailored midsole designs to absorb shock and reduce the risk of stress fractures or plantar fasciitis. Additionally, custom orthotics based on 3D foot scans and biomechanical analyses can be recommended to enhance performance and minimize injury. These should be coupled with a protocol for regular assessment of foot biomechanics to ensure ongoing effectiveness and fit.

By providing such detailed, actionable, and population-specific recommendations, the review can facilitate more effective translation of research findings into clinical practice, supporting individualized care and improved outcomes across various patient groups.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the critical role of proper shoe fit in promoting foot health and overall well-being across diverse populations, including the elderly, individuals with gout, and children with Down syndrome. Our study significantly contributes to the existing literature by highlighting not only the importance of proper footwear selection but also the practical application of customized footwear interventions tailored to specific populations such as children with Down syndrome and individuals with chronic conditions like gout. Unlike previous studies that often focus on aesthetic or general recommendations, our research provides evidence-based, population-specific guidelines that can be immediately integrated into clinical practice. Furthermore, the use of educational interventions, such as brochures for primary care providers, is shown to be effective in improving patient outcomes, offering a cost-effective and accessible solution that has not been extensively explored in earlier work. By incorporating innovative technologies like custom-fitted shoes and examining their impact on physical activity and podiatric health, this study bridges the gap between conventional and modern approaches, paving the way for future studies on personalized footwear solutions. These findings advocate for policy changes to include footwear education and access to therapeutic shoes as standard components in healthcare plans for at-risk populations, thereby enhancing the long-term quality of life and reducing healthcare costs. Our work not only reinforces the critical role of footwear in podiatric health but also sets a precedent for integrating technological and educational strategies into preventative and therapeutic interventions.

Author Contributions

R.T. and F.G. conceptualized and designed the study and was responsible for data acquisition. R.T. drafted the manuscript. D.D. provided supervision and guidance throughout the study. F.G. performed the editing of the manuscript. RT reviewed the manuscript and curated the methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tedeschi, R. What Are The Benefits of Five-Toed Socks? A Scoping Review. Reabil. Moksl. Slauga Kineziter. Ergoter. 2023, 1, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwaard, B.C.; Poppe, E.; Vanwanseele, B.; van der Horst, H.E.; Elders, P.J.M. Development and Evaluation of a Leaflet Containing Shoe Advice: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- van der Zwaard, B.C.; van der Horst, H.E.; Knol, D.L.; Vanwanseele, B.; Elders, P.J.M. Treatment of Forefoot Problems in Older People: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Podiatric Treatment with Standardized Shoe Advice. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jones, P.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Frykberg, R.; Davies, M.; Rowlands, A.V. Footwear Fit as a Causal Factor in Diabetes-Related Foot Ulceration: A Systematic Review. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, M.G.; Ouattas, A.; El-Refaei, N.; Momin, A.S.; Azarian, M.; Najafi, B. Assessing the Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Therapeutic Footwear in Reducing Foot Pain and Improving Function among Older Adults: A Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial. Gerontology 2024, 70, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Azhar, A.; Bergin, S.M.; Munteanu, S.E.; Menz, H.B. Footwear, Orthoses, and Insoles and Their Effects on Balance in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Gerontology 2024, 70, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kase, R.; Amemiya, A.; Okonogi, R.; Yamakawa, H.; Sugawara, H.; Tanaka, Y.L.; Komiyama, M.; Mori, T. Examination of the Effect of Suitable Size of Shoes under the Second Metatarsal Head and Width of Shoes under the Fifth Metatarsal Head for the Prevention of Callus Formation in Healthy Young Women. Sensors 2018, 18, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frecklington, M.; Dalbeth, N.; McNair, P.; Morpeth, T.; Vandal, A.C.; Gow, P.; Rome, K. Effects of a Footwear Intervention on Foot Pain and Disability in People with Gout: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.M.; Shields, N.; Landorf, K.B.; Buldt, A.K.; Taylor, N.F.; Evans, A.M.; Williams, C.M.; Menz, H.B.; Munteanu, S.E. Efficacy of Custom-Fitted Footwear to Increase Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome (ShoeFIT): Randomised Pilot Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.M.; Mattock, J.P.M.; Coltman, C.E.; Steele, J.R. Do the Footwear Profiles and Foot-Related Problems Reported by Netball Players Differ Between Males and Females? Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.M.; Mattock, J.P.M.; Coltman, C.E.; Steele, J.R. What Do Male Netball Players Want in Their Footwear? Design Recommendations for Netball-Specific Shoes for Men. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 113, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R. Briser Le Cycle Nocebo: Stratégies Pour Améliorer Les Résultats En Podiatrie. Douleurs Éval. Diagn. Trait. 2023, 24, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. Case Study: Gait Assessment of a Patient with Hallux Rigidus Before and After Plantar Modification. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 114, 109197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. L’impact Biomécanique Des Chaussures de Course Nike Sur Le Risque de Blessures: Une Revue de Littérature. J. Traumatol. Sport 2023, 41, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. Biomechanical Alterations in Lower Limb Lymphedema: Implications for Walking Ability and Rehabilitation. Phlebology 2023, 38, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R. Automated Mechanical Peripheral Stimulation for Gait Rehabilitation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. 2023, 9, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. Kinematic and Plantar Pressure Analysis in Strumpell-Lorrain Disease: A Case Report. Brain Disord. 2023, 11, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, G.; Brown, S.; Jude, E.; Bowling, F.L.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Reeves, N.D. Response to Comment on Orlando et al. Acute Effects of Vibrating Insoles on Dynamic Balance and Gait Quality in Individuals With Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Randomized Crossover Study. Diabetes Care 2024;47:1004-1011. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, e82–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathke, C.L.; Pimentel, V.C.d.A.; Alsina, P.J.; do Espírito Santo, C.C.; Dantas, A.F.O. de A. IoT-Based Wireless System for Gait Kinetics Monitoring in Multi-Device Therapeutic Interventions. Sensors 2024, 24, 5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puszczałowska-Lizis, E.; Lizis, S.; Dunaj, W.; Omorczyk, J. Evaluation of Professional Footwear and Its Relationships with the Foot Structure among Clinical Nurses. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2024, 26, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Qu, X. Pressure Pain Threshold of the Whole Foot: Protocol and Dense 3D Sensitivity Map. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 121, 104372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, E.; Cowley, E.; Bowen, C. The Experiences of Podiatrists Prescribing Custom Foot Orthoses and Patients Using Custom Foot Orthoses for Foot Pain Management in the United Kingdom: A Focus Group Study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2024, 17, e12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzadkiewicz, M.; Chylińska, J. Walking in Their Shoes: How Primary-Care Experiences of Adults Aged 50+ Reveal the Benefits of e-Learning Intervention for General Practitioners. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2023, 15, 1237–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Yuan, S. Kinematic Strategies for Sustainable Well-Being in Aging Adults Influenced by Footwear and Ground Surface. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; McCarthy, N.; Hall, A.; Shoesmith, A.; Lane, C.; Jackson, R.; Sutherland, R.; Groombridge, D.; Reeves, P.; Boyer, J.; et al. Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial to Determine the Impact of an Activity Enabling Uniform on Primary School Student’s Fitness and Physical Activity: Study Protocol for the Active WeAR Everyday (AWARE) Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajerian, M.; Garcia, J. Garments and Footwear for Chronic Pain. Front. Pain. Res. 2021, 2, 757240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Majumder, S.; Faisal, A.I.; Deen, M.J. Insole-Based Systems for Health Monitoring: Current Solutions and Research Challenges. Sensors 2022, 22, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongebloed-Westra, M.; Bode, C.; van Netten, J.J.; Ten Klooster, P.M.; Exterkate, S.H.; Koffijberg, H.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C. Using Motivational Interviewing Combined with Digital Shoe-Fitting to Improve Adherence to Wearing Orthopedic Shoes in People with Diabetes at Risk of Foot Ulceration: Study Protocol for a Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2021, 22, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Moghimi, M.A.; Naemi, R. A Mathematical Model to Investigate Heat Transfer in Footwear during Walking and Jogging. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Petersen, L.; Nester, C.J.; Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Skidmore, S.; Gijon-Nogueron, G. A Qualitative Study Exploring the Experiences and Perceptions of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Before and After Wearing Foot Orthoses for 6 Months. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, A.; Karabulut, G.; Terzioğlu, B. Standing in Others’ Shoes: Empathy and Positional Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.L.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. Undertaking a Scoping Review: A Practical Guide for Nursing and Midwifery Students, Clinicians, Researchers, and Academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenig, T.; Saxena, A.; Rice, H.M.; Hollander, K.; Tenforde, A.S. Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities with ‘Super Shoes’: Balancing Performance Gains with Injury Risk. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1472–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoe Technology Reduces Risk of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Available online: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/04/240419182004.htm (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Gumasing, M.J.J.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Jaurigue, J.; Saavedra, D.N.M.; Nadlifatin, R.; Chuenyindee, T.; Persada, S.F. The Effects of Biomechanical Risk Factors on Musculoskeletal Disorders among Baggers in the Supermarket Industry. Work 2023, 75, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Morrison, S.C.; Paterson, K.; Gobbi, K.; Burton, S.; Hill, M.; Harber, E.; Banwell, H. Young Children’s Footwear Taxonomy: An International Delphi Survey of Parents, Health and Footwear Industry Professionals. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howsam, N.; Reel, S.; Killey, J. A Preliminary Study Investigating the Overlay Method in Forensic Podiatry for Comparison of Insole Footprints. Sci. Justice 2022, 62, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puszczalowska-Lizis, E.; Lukasiewicz, A.; Lizis, S.; Omorczyk, J. The Impact of Functional Excess of Footwear on the Foot Shape of 7-Year-Old Girls and Boys. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmini, P.G.; Hegde, R.B.; Basavarajappa, B.K.; Bhat, A.K.; Pujari, A.N.; Gargiulo, G.D.; Gunawardana, U.; Jan, T.; Naik, G.R. Recent Innovations in Footwear and the Role of Smart Footwear in Healthcare—A Survey. Sensors 2024, 24, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.W.; Schlangen, M.; Winski, B.; Bolch, C. Podiatric Conditions Observed in Special Olympics Athletes: Contrasting Data from a USA versus an International Population. Foot 2024, 59, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. Other’s Shoes Also Fit Well: AI Technologies Contribute to China’s Blue Skies as Well as Carbon Reduction. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.; Park, H. Fit of Fire Boots: Exploring Internal Morphology Using Computed Tomography. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 30, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, K.L.; Hinman, R.S.; Metcalf, B.R.; McManus, F.; Jones, S.E.; Menz, H.B.; Munteanu, S.E.; Bennell, K.L. Effect of Foot Orthoses vs Sham Insoles on First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Osteoarthritis Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R. Assessment of Postural Control and Proprioception Using the Delos Postural Proprioceptive System. Reabil. Moksl. Slauga Kineziter. Ergoter. 2023, 2, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.E.; Scott, S.G.; Mingle, M. Viscoelastic Shoe Insoles: Their Use in Aerobic Dancing. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1989, 70, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.; Rohr, E.; Orendurff, M.; Shofer, J.; O’Brien, M.; Sangeorzan, B. The Effect of Walking Speed on Peak Plantar Pressure. Foot Ankle Int. 2004, 25, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).