Unlocking the Potential of Pick-Up Points in Last-Mile Delivery in Relation to Gen Z: Case Studies from Greece and Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Business opportunities, i.e., e-commerce opens doors for students. It showcases their entrepreneurial spirit.

- Skill development, i.e., e-commerce serves as a dynamic mastering ground for students, offering opportunities to acquire skills in virtual advertising and marketing, network layout, record evaluation, and customer service.

- The flexibility and convenience of online shopping attracts students, offering them the opportunity to shop anytime, anywhere. E-commerce not only saves time and money, but also puts a wide range of products and services at their fingertips.

2. Materials and Methods

- Gender;

- Age;

- Monthly income;

- Education;

- Residence (at the municipal level).

- Usage of courier services (Yes/No);

- Familiarity with the existing PUPs network in the Municipal of Thessaloniki (Yes/No);

- Level of usage of the PUPs network (5-point Likert scale);

- Types of goods purchased and picked up from PUPs (choosing from 11 types of goods);

- Criteria affecting their choice of PUP from which to pick up their purchased goods (choosing from 12 criteria—up to 5 choices);

- Evaluation of their experience using PUPs concerning how fast they received their purchased goods (5-point Likert scale);

- Expansion of the existing PUPs network (Yes/No);

- Evaluation of their experience using PUPs concerning the perceived level of safety and security while using PUPs (5-steps Likert scale);

- How environmentally friendly PUPs are relative to home deliveries (5-point Likert scale);

- Whether accessibility and easiness of use of PUPs are factors affecting their choice to purchase goods online (Yes/No).

3. Results

Descriptive Statistical Analysis

- Gender: For the Greek case study, 60.7% were female and 37.0% were male, while for the Italian case study, 49.4% of respondents were male and 50.6% were female (see Figure 1a).

- Age: For the Greek case study, most of the participants were between 18 and 24 years of age (59.1%). Eight out of ten were between 18 and 39 years of age (80.0%), while the other 19.2% was distributed between 40 and 64 years of age. Finally, just 0.8% of the participants were over 65 years of age. For the Italian case study, more than one out of two respondents were in the age group between 18 and 24 years old (51.1%); 20.6% of respondents were between 25 and 39 years old, so the total number of respondents under the age of 40 was 71.7%; and 28.3% were 40 or older, so only 3% were older than 64 (see Figure 1b).

- Monthly Income: For the Greek case study, over half of the participants stated that their monthly income was no more than EUR 400 (54.2%). Almost one out of four (26.0%) stated that her/his monthly income was somewhere between EUR 401 and EUR 1.200. Finally, only 14.0% of the participants stated that their monthly income was somewhere between EUR 1.291 and EUR 2.000, and 5.7% stated that their monthly income exceeded EUR 2.000. It is quite evident that most of the participants’ monthly income was below half of the minimum monthly salary in Greece (EUR 830 as of 1 April 2024 [39]). For the Italian case study, 36.5% of respondents stated that their personal income was lower than EUR 800/month. Most respondents stated that, somehow, their monthly income was between EUR 800 and 2000/month (52.8%). The remaining 10.7% declared income higher than EUR 2000/month (see Figure 1c).

- Education: For the Greek case study, over half of the participants (as expected) were students at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (58.4%). Another 27.0% were highly educated, holding MSc or/and PhD degrees, while only 12.2% held a university degree without any further educational evolution. For the Italian case study, almost half of the respondents (as expected) were university students (49.4%). In addition, 33% were university graduates, while only 3.9% declared a higher level of education, and 13.7% of respondents did not declare an educational level higher than secondary school (Figure 1d);

- Residence (Municipality): For the Greek case study, over 60% of the participants stated the Municipality of Thessaloniki as their location of residence (61.8%), 8.1% the Municipality of Kalamaria, and 5.9% the Municipality of Neapoli-Sykies. The remaining 14.2% was distributed in the rest of the Municipality of Thessaloniki’s metropolitan area. For the Italian case study, all respondents worked or studied at University of Enna “Kore”; therefore, all respondents frequented the same city. Among them, 45.1% were residents of Enna, while the remainder were residents of other Sicilian provinces. In particular, the largest proportion related to the provinces closest to Enna, and of those with the largest population shares, 12.9% come from Catania, 12% from Palermo, and 12.9% from Caltanissetta (see Figure 1e).

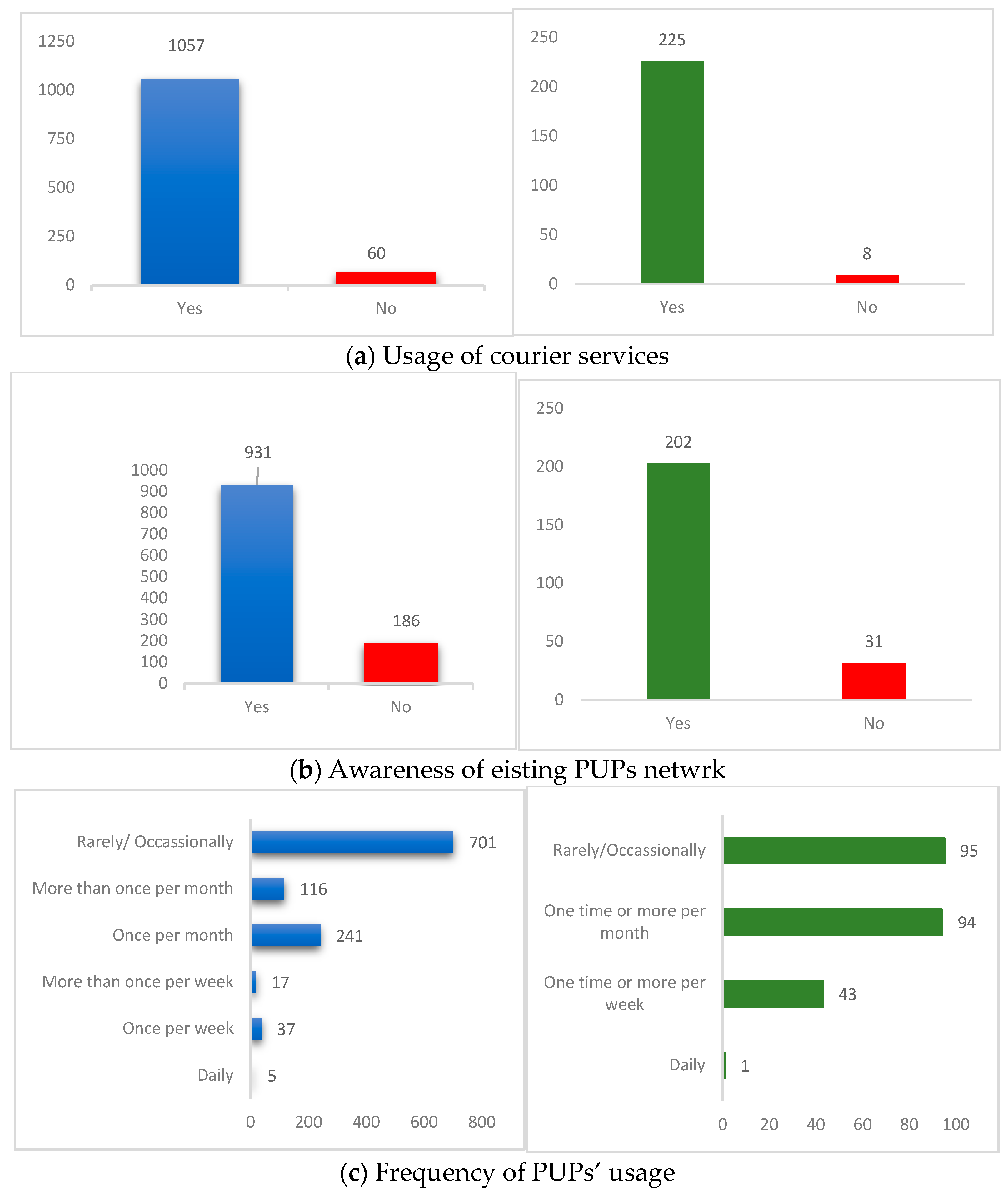

- Usage of courier services: For the Greek case study, almost 95% (94.6%) of the participants stated that they used courier services to receive and/or send small parcels, while the remaining 5% (5.4%) stated the opposite. For the Italian case study, almost all the respondents used courier services (96% against 4%) (Figure 2a).

- Awareness of existing PUPs network: For the Greek case study, the percentage of the participants that were aware of the existence of PUPs in the city of Thessaloniki was considered as high (83.4%). However, 16.6% of the participants were not aware of this network, leaving significant room for the administrators of the PUPs network to bring it to their knowledge. For the Italian case study, awareness of existing networks was commonly spread across the sample. In total, 87% of respondents stated that they knew of the possibility of picking up parcels at specific points (Figure 2b).

- Frequency of PUPs usage: For the Greek case study, although most of the participants used courier services and were aware of the existence of PUPs, they rarely/occasionally used them (62.8%). Daily, only 0.4% of the participants used PUPs, while 3.3% used them once per week, 1.5% more than once per week, 21.6% once per month, and 10.45 more than once per month. For the Italian case study, a large share of respondents (40.8%) used pick-up points only scarcely, even if a larger share was aware of pick-up points and used courier services. In total, 40.3% of respondents used pick-up points monthly, while 18.5% declared that they used pick-up points on a weekly basis. Only one respondent used pick-up points daily (Figure 2c).

- Types of products purchased using PUPs: For the Greek case study, the next question concerned the types of products the participants prefer to purchase using the PUPs network. It must be mentioned that for this question, each participant could choose up to five answers from a specific list of products (electric devices, clothing/footwear, products for personal care, home decoration, office consumables, pet supplies, sport equipment, pharmaceuticals and parapharmaceuticals, toys, gifts, and others). The most preferred type of goods was clothing/footwear, followed by products for personal care and electric devices. The least preferable products were pet supplies, toys, and home decoration. For the Italian case study, twelve categories were indicated, and each respondent was asked to choose up to five. The most requested categories were clothing (indicated by 61.4% of the total) and books (52.8%). The least requested were pet supplies and sport accessories (both less than 10%) (Figure 2d).

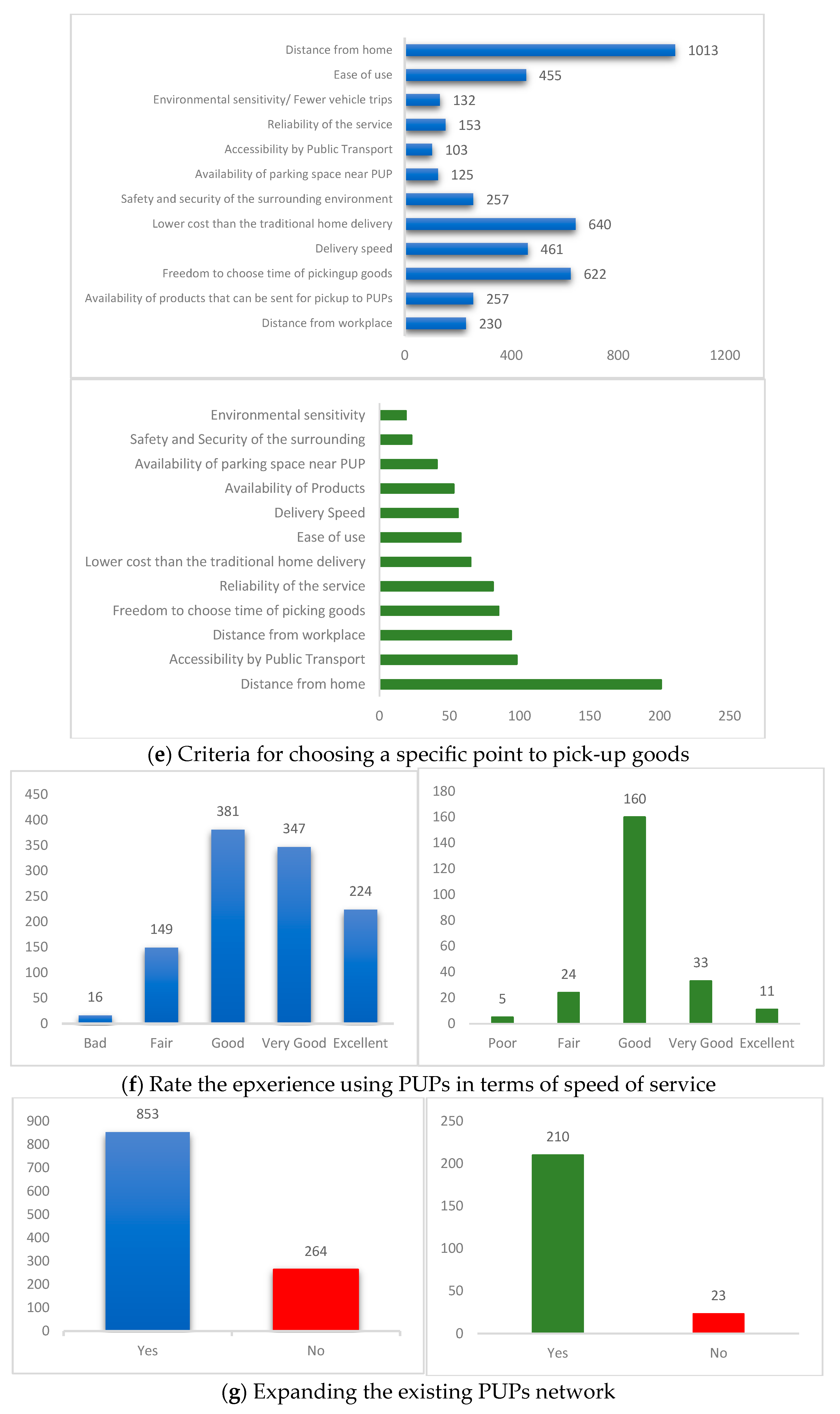

- Criteria for choosing a specific point to pick up goods: For the Greek case study, again, for this question, the participants had the ability to choose up to five answers from a provided list. The criterion with most answers concerned the distance of PUPs from the participant’s home location, followed by the lower cost of using PUPs compared to traditional home delivery services and the freedom PUPs provide to the people to pick up their goods whenever they want. The least preferable criterion was the accessibility of the PUP by public transport modes, followed by the availability of parking space for their private cars near the PUP. For the Italian case study, most respondents (86.3%) indicated distance from home, indicating that proximity to home is a real driving reason for choosing a pick-up point. The least indicated criterion was linked to environmental practices, indicated by 8.2% of respondents (Figure 2e).

- Rate the experience of using PUPs in terms of speed of service: For the Greek case study, over 50.0% (51.2%) of the participants rated, using a 5-point Likert scale (Bad, Fair, Good, Very Good, and Excellent), their experience using PUPs in terms of speed of service as Very Good or Excellent. The percentage of participants having a positive experience increased to 85.2% by including those that rated their experience as Good. Thus, the percentage of participants with a negative experience with using PUPs (always in relation to the speed of service) was almost 15.0% (14.8%). For the Italian case study, most responses were concentrated in the central category (Good, 68.7%), indicating an overall good relationship without exaggerated enthusiasm. The percentage of respondents who indicated Very Good or Excellent was, overall, 18.9%, while the remaining 12.4% indicated Poor or Fair (Figure 2f).

- Expanding the existing PUPs network: For the Greek case study, over ¾ of the participants had a positive attitude regarding expanding the existing network of PUPs (76.4%), while the other 23.6% were negative toward such a possibility. For the Italian case study, a vast majority (90.1%) of the analyzed sample declared themselves to feel positive regarding the possibility of extending the pick-up point network (Figure 2g).

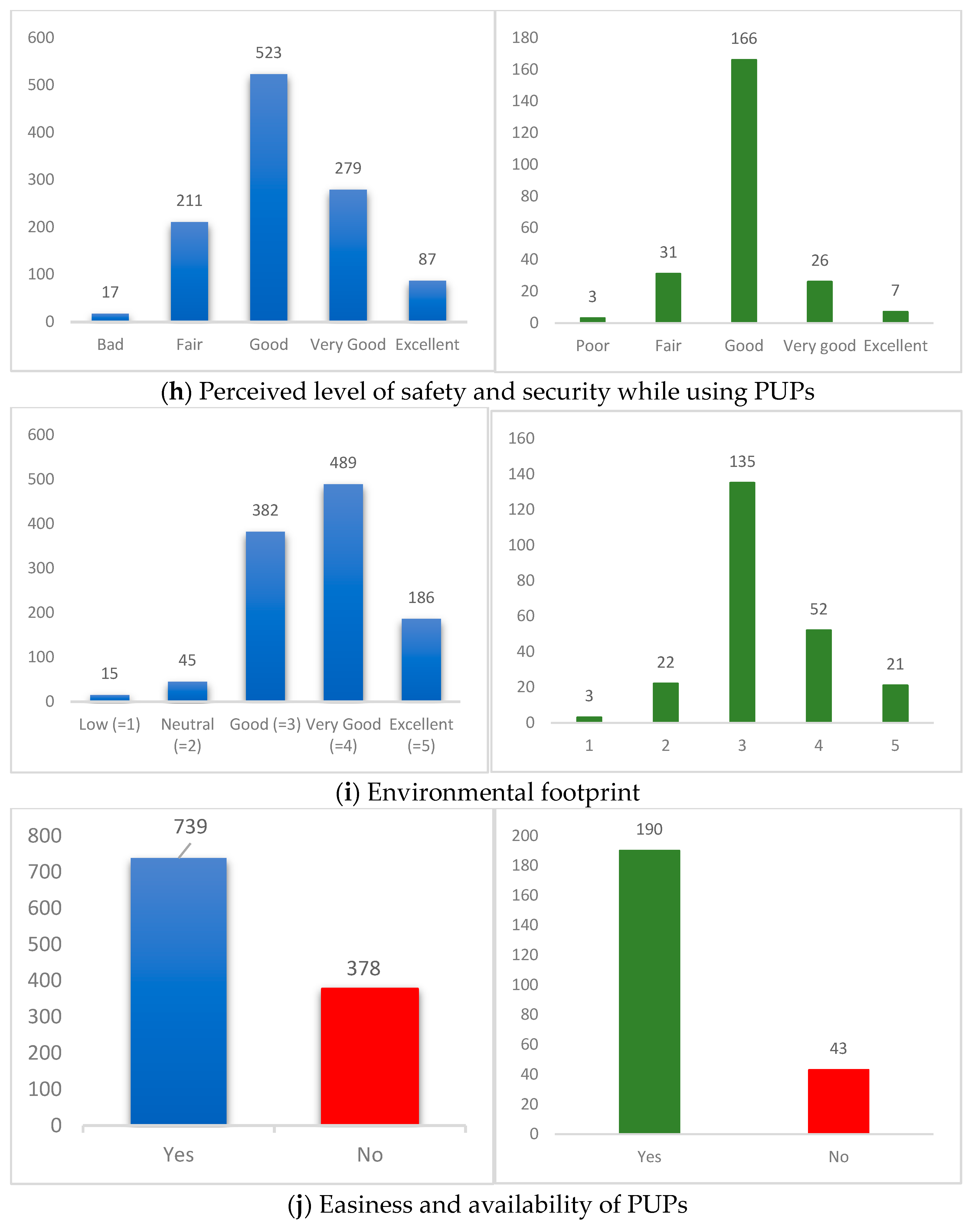

- Perceived level of safety and security while using PUPs: For the Greek case study, most participants (79.6%) felt secure and safe while using PUPs (a 5-point Likert scale was used for this question, allowing the participants to choose among Bad, Fair, Good, Very Good, and Excellent). However, a significant percentage of the participants (20.4%) felt insecure and unsafe while using PUPs, which is a rather important issue for the administrators to address. For the Italian case study, although most respondents indicated a Good or higher condition (85.7%), there was a significant minority who declared a feeling of insecurity (Figure 2h)

- Environmental footprint: In this question, the participants were asked to evaluate the environmental footprint of PUPs compared to traditional home deliveries. A 5-point Likert scale was used (Low, Neutral, Good, Very Good, Excellent), allowing the participants to estimate whether PUPs are more environmentally friendly than home deliveries concerning the produced environmental footprint from both the couriers and the users. If a person chose 1, that means that, in his/her estimation, home deliveries are more environmentally friendly than PUPs. For the Greek case study, almost 95% of the participants (94.6%) estimated that PUPs are more environmentally friendly compared to traditional home deliveries, while the other 5.3% estimated the opposite. For the Italian case study, most respondents (57.9%) indicated a good environmental impact, comparable to that of deliveries, while a significant minority, 31.3% overall, indicated a better environmental impact. The remaining 10.7% believed that home deliveries have an overall better environmental impact than pick-up points (see Figure 2i).

- Easiness and availability of PUPs: For the last question, the participants were asked whether PUPs’ easiness of use, as well as their 24/7 availability, are factors that are taken into consideration by them in purchasing online goods. For the Greek case study, most of the participants replied positively (66.2%), while the remaining 33.8% replied negatively. For the Italian case study, approximately 81.5% of respondents believed that 24/7 accessibility and convenience is a factor that influences purchases at pick-up points (see Figure 2j).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Strategies to bridge the awareness–usage gap: As mentioned above, awareness of PUPs is high, but their usage remains modest. To bridge this gap, educational campaigns highlighting PUPs’ benefits (convenience, cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness) could be implemented. Collaboration with e-commerce retailers offering PUP incentives and expanding the PUPs network to more convenient locations, especially near residential areas, could further entice users.

- Enhancing security and user comfort: Security concerns surfaced, as some users felt it was unsafe to use PUPs. To address this issue, improving lighting and establishing a dedicated customer support channel for PUP-related inquiries or concerns will allow users to report issues or seek assistance properly. By implementing a multi-layered approach that combines physical security measures, clear communication, and user-friendly technology, PUP services can become a more secure and convenient option for e-commerce deliveries.

- Tailoring PUP services to demographics: Different demographics have varying needs and preferences regarding PUPs. Offering a wider variety of PUP locations, including those close to residential areas for proximity-conscious users, is essential. Partnering with businesses frequented by younger demographics to establish PUP locations within those businesses could be explored.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comi, A.; Nuzzolo, A. Exploring the relationships between e-shopping attitudes and urban freight transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, D.M. What will make Generation Y and Generation Z to continue to use online food delivery services: A uses and gratifications theory perspective. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, C.K.; Tiwari, V.; Tiwari, V. Generation “Z” willingness to participate in crowdshipping services to achieve sustainable last-mile delivery in emerging market. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 19, 2446–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudirjo, F.; Lotte, L.N.A.; Sutaguna, I.N.T.; Risdwiyanto, A.; Yusuf, M. The Influence of Generation Z Consumer Behavior on Purchase Motivation in E-Commerce Shoppe. Profit J. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2023, 2, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Messias, I.; Oliveira, A. Technological Acceptance of E-Commerce by Generation Z in Portugal. Information 2024, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Verhetsel, A. The sustainability of the urban layer of e-commerce deliveries: The Belgian collection and delivery point networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 2300–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeijer, R.; Buijs, P. A greener last mile: Analyzing the carbon emission impact of pickup points in last-mile parcel delivery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 186, 113630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Census. Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2021. Available online: https://elstat-outsourcers.statistics.gr/Census2022_GR.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- City Population, Province of Sicilia. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/italy/sicilia/086__enna/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area, Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thessaloniki_metropolitan_area (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Available online: https://www.auth.gr/en/university/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Libera Universita della Sicila Centrale “Kore” di Enna. Available online: https://ustat.mur.gov.it/dati/didattica/italia/atenei-non-statali/enna-kore (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Indici Demografici e Struttura di Enna. Available online: https://www.tuttitalia.it/sicilia/71-enna/statistiche/indici-demografici-struttura-popolazione/ (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Locus. Pickup points. In Supply Chain & Logistics Glossary. Available online: https://locus.sh/resources/glossary/pickup-points/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Tuncali Yaman, T.; Yaylalı, S. Ideal Location Selection for Contactless Parcel Pick-Up Points. Int. J. Anal. Hierarchy Process 2023, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Ye, X.; Chen, Y. Pick-up point recommendation strategy based on user incentive mechanism. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Wu, G.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Ji, M.; Xu, P.; et al. Pick-Up Point Recommendation Using Users’ Historical Ride-Hailing Orders. In Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications; Wang, L., Segal, M., Chen, J., Qiu, T., Eds.; WASA 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. A Pick-Up Points Recommendation System for Ridesourcing Service. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakanmi, O.O.; Odeyemi, K.O. A Collaborative 1-to-n On-Demand Ride Sharing Scheme Using Locations of Interest for Recommending Shortest Routes and Pick-up Points. Int. J. Intell. Trasnport. Syst. Res. 2021, 19, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moussaoui, A.E.; Benbba, B.; Jaegler, A.; El Moussaoui, T.; El Andaloussi, Z.; Chakir, L. Consumer Perceptions of Online Shopping and Willingness to Use Pick-Up Points: A Case Study of Morocco. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Ryu, G.S. The moderating effects of perceived in-store experience and in-store return convenience on the relationship between buy-online-pick-up-in-store (BOPIS) usage and customer satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, O.; Kiss, M. The impact of perceived service quality on customers’ repurchase intention: Mediation effect of price perception. Innov. Mark. 2022, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Tesoriere, G.; Al-Rashid, M.A.; Campisi, T. Pick-Up Point Location Optimization Using a Two-Level Multi-objective Approach: The Enna Case Study. In Computational Science and Its Applications, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2023 Workshops, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M., Garau, C., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14106, p. 14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masteguim, R.; Cunha, C.B. An Optimization-Based Approach to Evaluate the Operational and Environmental Impacts of Pick-Up Points on E-Commerce Urban Last-Mile Distribution: A Case Study in São Paulo, Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.; Vaz de Magalhães, D.J.A.; Medrado, L. Demand analysis for pick-up sites as an alternative solution for home delivery in the Brazilian context. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 39, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, S.; Field, J.M. Development and validation of the pick-up service quality scale of the buy-online-pick-up-in-store service. Oper. Manag. Res. 2020, 13, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.-L.; Jang, H.; Fang, M.; Peng, K. Determinants of customer satisfaction with parcel locker services in last-mile logistics. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2022, 38, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. What’s in the parcel locker? Exploring customer value in e-commerce last mile delivery. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 112, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wong, Y.D.; Teo, C.-C. Parcel self-collection for urban last-mile deliveries: A review and research agenda with a dual operations-consumer perspective. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 16, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, S.S.; Nassir, N.; Thompson, R.G.; Ghaderi, H. Last-Mile logistics with on-premises parcel Lockers: Who are the real Beneficiaries? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, A.; Diehl, C.; Dalla Chiara, G.; Goodchild, A. Do parcel lockers reduce delivery times? Evidence from the field. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 172, 103070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, H.; Zhang, L.; Tsai, P.-W.; Woo, J. Crowdsourced last-mile delivery with parcel lockers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 251, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Digital Commerce: A Growth Opportunity for Greece. 21 May 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-commerce-a-growth-opportunity-for-greece (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration. Greece Country Commercial Guide. 2024. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/greece-country-commercial-guide (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Karakatsani, E. Greece Economy Briefing: The Rapid Growth of E-Commerce in Greece. Weekly Briefing, Chinea-CEE Institute, 48. 2022. Available online: https://china-cee.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022e02_Greece.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- EUROSTAT. E-Commerce Statistics for Individuals. Eurostat Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=E-commerce_statistics_for_individuals&oldid=629584#Main_points (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Campisi, T.; Russo, A.; Bouhouras, E.; Tesoriere, G.; Basbas, S. The Increase in E-Commerce Purchases and the Impact on the Newer European City Logistics Development. Open Transp. J. 2023, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerial Decision 25058/2024-ΦΕΚ 1974/Β/29-3-2024 of the Hellenic Republic. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/kat-ergasia-koinonike-asphalise/ya-25058-2024.html (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. News Release, Regional GDP per Capita Ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU Average in 2018. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/10474907/1-05032020-AP-EN.pdf/81807e19-e4c8-2e53-c98a-933f5bf30f58 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Russo, A.; Basbas, S.; Bouhouras, E.; Tesoriere, G.; Campisi, T. The Study of the 5-min Walking Accessibility for Pickup Points in Thessaloniki: Enhancing Logistics’ Last Mile Sustainability. In Computational Science and Its Applications, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2024 Workshops, Hanoi, Vietnam, 7 November 2024; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Taniar, D., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Faginas Lago, M.N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhouras, E.; Koenta, A.; Giannoudis, V.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T. Investigating Commercial Vehicles’ Parking Habits in Urban Areas: The Case of Thessaloniki, Greece. In Computational Science and Its Applications, Proceedings of the ICCSA 2024 Workshops, Hanoi, Vietnam, 7 November 2024; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Taniar, D., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Faginas Lago, M.N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metropolitan Area of Thessaloniki | City of Enna | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (residents) | 1,092,919 [8] | 153,589 [9] |

| Total area (km2) | 1285.608 [10] | 2575 [9] |

| University | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | University of Enna Kore |

| Number of students | 90,299 [11] | 4900 [12] |

| Number of academic staff | 2728 [11] | 300 [12] |

| Number of questionnaires analyzed (percentage over total number of students and academic staff) | 1117 (1.2%) | 240 (4.6%) |

| Confidence level (margin of error ± 5%) | 95% | 88% |

| Topic | Reference |

|---|---|

| Pick-up Point Recommendation | [16,17,18,19,20] |

| Consumer Behavior Regarding Pick-up Points | [21,22,23] |

| Pick-up Point Location and Optimization | [18,24,25,26] |

| Pick-up Point Service Quality | [27,28,29,30] |

| Pick-up Point Lockers | [31,32,33] |

| Variable Name | Variable Label | Categories and Label Values | # Observations Greek Case Study | # Observations Italian Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Use of courier service | Do you Use courier services? | (1) Yes (0) No | 1095 | 233 |

| Weekly use of pick-up points | If you use pick-up points, do you use them at least once per week? (i.e., this includes the answers: once per week; more than once per week; daily) | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 233 |

| How do you evaluate the environmental footprint of delivery pick-up points compared to home delivery? | ||||

| Environmental footprint of pick-up points: Larger | Larger or somehow larger | (1) Yes (0) No | 1081 | 233 |

| Environmental footprint of pick-up points: Same | Neither larger nor smaller | (1) Yes (0) No | 1081 | 233 |

| Environmental footprint of pick-up points: Smaller | Smaller or somehow smaller | (1) Yes (0) No | 1081 | 233 |

| Which are your criteria for choosing a specific pick-up point? (Only those who indicated making use of pick-up points can answer) | ||||

| Time flexibility | Flexibility in delivery time | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 225 |

| Distance from home | Distance from your home | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 225 |

| Lower cost | Lower cost compared to home delivery | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 225 |

| Delivery speed | Speed of delivery and service | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 225 |

| User-friendliness | Easy use of the service | (1) Yes (0) No | 1055 | 225 |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Gender | Gender of respondent | (1) Male (0) Female | 1300 | 233 |

| Age | Age category of the respondent | (1) 18–24 (2) 25–39 (3) 40–54 (4) 55–64 (5) 65+ | 1300 | 233 |

| University student | Education level of the respondent | (1) University student or completed secondary education (0) Graduate of tertiary education | 1298 | 233 |

| Low income class | Monthly income of the respondent ranging from EUR 0 to 800 | (1) Yes (0) No | 1299 | 233 |

| High income class | Monthly income of the respondent above EUR 1600 | (1) Yes (0) No | 1299 | 233 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of Courier Service | Weekly Use of Pick-Up Points | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Larger | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Same | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Smaller | |

| Gender | −0.435 *** | 0.611 *** | −0.462 | 0.015 | 0.070 |

| (0.166) | (0.216) | (0.283) | (0.112) | (0.097) | |

| Age | 0.034 | 1.276 | −0.594 *** | −1.187 *** | 1.257 *** |

| (0.395) | (1.008) | (0.171) | (0.229) | (0.216) | |

| Age2 | 0.001 | −0.235 | 0.148 *** | 0.240 *** | −0.261 *** |

| (0.099) | (0.180) | (0.048) | (0.039) | (0.038) | |

| University student | −0.494 ** | −0.205 | 0.113 | −0.090 | 0.065 |

| (0.250) | (0.302) | (0.284) | (0.142) | (0.131) | |

| Low income class | −0.298 | −0.074 | 0.043 | 0.079 | −0.082 |

| (0.186) | (0.357) | (0.396) | (0.153) | (0.103) | |

| High income class | −0.104 | 0.605 *** | 0.343 | −0.778 *** | 0.624 *** |

| (0.440) | (0.228) | (0.344) | (0.243) | (0.219) | |

| Observations | 1094 | 1054 | 1080 | 1080 | 1080 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.019 | 0.066 | 0.011 | 0.035 | 0.034 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of Courier Service | Weekly Use of Pick-Up Points | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Larger | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Same | Environmental Footprint of Pick-Up Points: Smaller | |

| Gender | 0.042 | 0.161 | 0.499 | −0.147 | −0.139 |

| (0.725) | (0.345) | (0.431) | (0.271) | (0.291) | |

| Age | 2.803 *** | −0.674 * | −2.204 *** | 0.454 | −0.239 |

| (0.879) | (0.356) | (0.514) | (0.319) | (0.372) | |

| Age2 | −0.545 *** | 0.096 | 0.418 *** | −0.046 | −0.055 |

| (0.187) | (0.079) | (0.106) | (0.075) | (0.097) | |

| University student | 0.683 | −0.917 *** | −0.459 | 0.146 | −0.302 |

| (0.751) | (0.338) | (0.434) | (0.281) | (0.306) | |

| Low income class | −0.103 | −1.804 *** | −0.041 | −0.716 ** | 0.401 |

| (0.758) | (0.579) | (0.509) | (0.323) | (0.339) | |

| High income class | 1.911 | 0.637 | −0.043 | −0.162 | 0.047 |

| (1.391) | (0.414) | (0.604) | (0.365) | (0.394) | |

| Observations | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.152 | 0.152 | 0.052 | 0.068 | 0.079 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Flexibility | Distance from Home | Lower Cost | Delivery Speed | User Friendliness | |

| Gender | 0.174 *** | 0.116 | −0.125 | 0.001 | 0.040 |

| (0.046) | (0.139) | (0.096) | (0.062) | (0.105) | |

| Age | 0.707 *** | 0.219 | 0.665 ** | 0.411 | 0.108 |

| (0.244) | (0.702) | (0.304) | (0.295) | (0.179) | |

| Age2 | −0.132 ** | −0.070 | −0.189 *** | −0.109 * | −0.015 |

| (0.056) | (0.131) | (0.071) | (0.063) | (0.029) | |

| University student | −0.071 | 0.086 | −0.108 | 0.079 | 0.172 |

| (0.106) | (0.215) | (0.116) | (0.129) | (0.112) | |

| Low income class | 0.053 | 0.386 *** | 0.074 | 0.048 | −0.054 |

| (0.125) | (0.147) | (0.092) | (0.084) | (0.124) | |

| High income class | −0.118 | 0.434 | −0.459 | −0.405 ** | 0.235 |

| (0.260) | (0.336) | (0.305) | (0.159) | (0.173) | |

| Observations | 1054 | 1054 | 1054 | 1054 | 1054 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.014 | 0.004 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Flexibility | Distance from Home | Lower Cost | Delivery Speed | User Friendliness | |

| Gender | −0.613 ** | 0.432 | 0.539 * | −0.228 | 0.581 |

| (0.278) | (0.391) | (0.305) | (0.306) | (0.299) | |

| Age | 0.313 | 0.519 | −1.013 *** | −0.892 ** | 0.079 |

| (0.323) | (0.425) | (0.341) | (0.355) | (0.328) | |

| Age2 | −0.111 | −0.055 | 0.215 *** | 0.149 * | 0.047 * |

| (0.079) | (0.109) | (0.077) | (0.082) | (0.079) | |

| University student | −0.181 | 0.727 * | −0.211 | 0.181 | −0.418 |

| (0.281) | (0.388) | (0.309) | (0.317) | (0.295) | |

| Low income class | −0.492 | 0.306 | −0.514 | −0.232 | −1.861 *** |

| (0.328) | (0.411) | (0.361) | (0.353) | (0.384) | |

| High income class | −0.123 | 1.121 ** | −0.468 | −0.259 | −0.327 |

| (0.359) | (0.546) | (0.401) | (0.406) | (0.362) | |

| Observations | 225 | 225 | 225 | 225 | 225 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.056 | 0.058 | 0.031 | 0.012 | 0.282 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Variance | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gender | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 1.66 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1 | 5 |

| student | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| income_1class | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 |

| income_2class | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 0 | 1 |

| income_3class | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0 | 1 |

| courier_service | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0 | 1 |

| pickup_points_weekly | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_more | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_same | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_less | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| time_flexibility | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| distance_home | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0 | 1 |

| delivery_speed | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| user_friendliness | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Variance | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gender | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 1.92 | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1 | 5 |

| student | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| income_1class | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| income_2class | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| income_3class | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

| courier_service | 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0 | 1 |

| pickup_points_weekly | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_more | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_same | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| enviromental_footprint_less | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 |

| time_flexibility | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

| distance_home | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0 | 1 |

| delivery_speed | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| user_friendliness | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouhouras, E.; Ftergioti, S.; Russo, A.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T.; Symeon, P. Unlocking the Potential of Pick-Up Points in Last-Mile Delivery in Relation to Gen Z: Case Studies from Greece and Italy. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10629. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210629

Bouhouras E, Ftergioti S, Russo A, Basbas S, Campisi T, Symeon P. Unlocking the Potential of Pick-Up Points in Last-Mile Delivery in Relation to Gen Z: Case Studies from Greece and Italy. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(22):10629. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210629

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouhouras, Efstathios, Stamatia Ftergioti, Antonio Russo, Socrates Basbas, Tiziana Campisi, and Pantelis Symeon. 2024. "Unlocking the Potential of Pick-Up Points in Last-Mile Delivery in Relation to Gen Z: Case Studies from Greece and Italy" Applied Sciences 14, no. 22: 10629. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210629

APA StyleBouhouras, E., Ftergioti, S., Russo, A., Basbas, S., Campisi, T., & Symeon, P. (2024). Unlocking the Potential of Pick-Up Points in Last-Mile Delivery in Relation to Gen Z: Case Studies from Greece and Italy. Applied Sciences, 14(22), 10629. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210629