Reviewing Breakthroughs and Limitations of Implantable and External Medical Device Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Spinal Cord

1.2. Spinal Cord Injury

2. Study Selection Criteria

3. Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury

3.1. Functional Electrical Simulation (FES) Systems

3.2. Epidural Electrical Stimulation (EES)

3.3. ‘SMART’ Implants and Devices

3.4. Exoskeletons and Robotic Systems

3.5. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

3.6. Brain–Computer Interface Technology Using AI

4. Table of Studies

5. Discussion and Future Directions

5.1. Methodological Quality and Evidence Gaps

5.2. Limitations of SCI Device-Based Therapies

5.2.1. Power Supply and Device Longevity

5.2.2. Wireless Data Logging and Adaptability

5.2.3. Surgical Risk and Anatomical Constraints

5.2.4. Usability, Training, and Maintenance

5.2.5. Cost and Accessibility

5.2.6. Regulatory and Health System Integration

5.3. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhind, J. How Many Spinal Cord Injuries Occur Each Year? JMW Solicitors. 2023. Available online: https://www.jmw.co.uk/articles/spinal-injuries/how-many-spinal-cord-injuries-each-year (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Anwar, M.A.; Al Shehabi, T.S.; Eid, A.H. Inflammogenesis of Secondary Spinal Cord Injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Monteiro, A.; Salgado, A.J.; Monteiro, S.; Silva, N.A. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches for Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Das, J.M.; Emmady, P.D. Spinal Cord Injuries; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560721/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Dowlati, E. Spinal cord anatomy, pain, and spinal cord stimulation mechanisms. Semin. Spine Surg. 2017, 29, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrow-Mortelliti, M.; Jimsheleishvili, G.; Reddy, V. Physiology, Spinal Cord; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544267/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fallahi, M.S.; Azadnajafabad, S.; Maroufi, S.F.; Pour-Rashidi, A.; Khorasanizadeh, M.; Sattari, S.A.; Faramarzi, S.; Slavin, K.V. Application of Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. World Neurosurg. 2023, 174, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinger, J.L.; Foldes, S.; Bruns, T.M.; Wodlinger, B.; Gaunt, R.; Weber, D.J. Neuroprosthetic technology for individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2013, 36, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Vardalakis, N.; Wagner, F.B. Neuroprosthetics: From sensorimotor to cognitive disorders. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Vidal, J.L.; Bhagat, N.A.; Brantley, J.; Cruz-Garza, J.G.; He, Y.; Manley, Q.; Nakagome, S.; Nathan, K.; Tan, S.H.; Zhu, F.; et al. Powered exoskeletons for bipedal locomotion after spinal cord injury. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sadowsky, C.; Obst, K.; Meyer, B.; McDonald, J. Functional Electrical Stimulation in Spinal Cord Injury: From Theory to Practice. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2012, 18, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.H.; Triolo, R.J.; Elias, A.L.; Kilgore, K.L.; DiMarco, A.F.; Bogie, K.; Vette, A.H.; Audu, M.L.; Kobetic, R.; Chang, S.R.; et al. Functional Electrical Stimulation and Spinal Cord Injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 25, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.; Decker, M.; Hwang, J.; Wang, B.; Kitchen, K.; Ding, Z.; Ivy, J. Functional electrical stimulation cycling improves body composition, metabolic and neural factors in persons with spinal cord injury. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling for Spinal Cord Injury. Physiopedia. 2012. Available online: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Functional_Electrical_Stimulation_Cycling_for_Spinal_Cord_Injury (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Berkelmans, R. Fes cycling. J. Autom. Control 2008, 18, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Li, S.; Ahmed, R.U.; Yam, Y.M.; Thakur, S.; Wang, X.-Y.; Tang, D.; Ng, S.; Zheng, Y.-P. Development of a battery-free ultrasonically powered functional electrical stimulator for movement restoration after paralyzing spinal cord injury. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamian, B.A.; Siegel, N.; Nourie, B.; Serruya, M.D.; Heary, R.F.; Harrop, J.S.; Vaccaro, A.R. The role of electrical stimulation for rehabilitation and regeneration after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2022, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Khalil, R.E.; Lester, R.M.; Dudley, G.A.; Gater, D.R. Paradigms of lower extremity electrical stimulation training after spinal cord injury. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 132, e57000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moineau, B.; Marquez-Chin, C.; Alizadeh-Meghrazi, M.; Popovic, M.R. Garments for functional electrical stimulation: Design and proofs of concept. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2019, 6, 2055668319854340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbinot, G.; Li, G.; Gauthier, C.; Musselman, K.E.; Kalsi-Ryan, S.; Zariffa, J. Functional electrical stimulation therapy for upper extremity rehabilitation following Spinal Cord Injury: A pilot study. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2023, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.D.; Wilson, J.R.; Korupolu, R.; Pierce, J.; Bowen, J.M.; O’REilly, D.; Kapadia, N.; Popovic, M.R.; Thabane, L.; Musselman, K.E. Multicentre, single-blind randomised controlled trial comparing MyndMove neuromodulation therapy with conventional therapy in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A protocol study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalif, J.I.; Chavarro, V.S.; Mensah, E.; Johnston, B.; Fields, D.P.; Chalif, E.J.; Chiang, M.; Sutton, O.; Yong, R.; Trumbower, R.; et al. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation for Spinal Cord Injury in Humans: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinal Cord Injury Epidural Stimulation. Mayo Clinic. 2021. Available online: https://www.mayo.edu/research/clinical-trials/cls-20167853 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Ren, Y.; Mo, L.; Lu, J.; Zhu, P.; Yin, M.; Jia, W.; Liang, F.; Han, X.; Zhao, J. Epidural electrical stimulation for functional recovery in incomplete spinal cord injury. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2025, 6, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.Y.; Choi, E.H.; Gattas, S.; Brown, N.J.; Hong, J.D.; Limbo, J.N.; Chan, A.Y. Epidural electrical stimulation for spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.J.; Lavrov, I.A.; Sayenko, D.G.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Gill, M.L.; Strommen, J.A.; Calvert, J.S.; Drubach, D.I.; Beck, L.A.; Linde, M.B.; et al. Enabling task-specific volitional motor functions via spinal cord neuromodulation in a human with paraplegia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.L.; Grahn, P.J.; Calvert, J.S.; Linde, M.B.; Lavrov, I.A.; Strommen, J.A.; Beck, L.A.; Sayenko, D.G.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Drubach, D.I.; et al. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S.; Gerasimenko, Y.; Hodes, J.; Burdick, J.; Angeli, C.; Chen, Y.; Ferreira, C.; Willhite, A.; Rejc, E.; Grossman, R.G.; et al. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after Motor Complete Paraplegia: A Case Study. Lancet 2011, 377, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.A.; Edgerton, V.R.; Gerasimenko, Y.P.; Harkema, S.J. Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans. Brain 2014, 137, 1394–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PelicanSSNadmin. Smart Implants Used to Monitor Spinal Fusion Healing—Spinal Surgery News. Spinal Surgery News, 28 June 2022. Available online: https://www.spinalsurgerynews.com/2022/06/smart-implants-used-to-monitor-spinal-fusion-healing/95622 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Barri, K.; Zhang, Q.; Swink, I.; Aucie, Y.; Holmberg, K.; Sauber, R.; Altman, D.T.; Cheng, B.C.; Wang, Z.L.; Alavi, A.H. Patient-Specific Self-Powered Metamaterial Implants for Detecting Bone Healing Progress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodington, B.J.; Lei, J.; Carnicer-Lombarte, A.; Güemes-González, A.; Naegele, T.E.; Hilton, S.; El-Hadwe, S.; Trivedi, R.A.; Malliaras, G.G.; Barone, D.G. Flexible circumferential bioelectronics to enable 360-degree recording and stimulation of the spinal cord. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wraparound Implants Represent New Approach to Treating Spinal Cord Injuries. University of Cambridge. 2024. Available online: https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/wraparound-implants-represent-new-approach-to-treating-spinal-cord-injuries (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Spinal Cord Injury Braces & Walking Systems. Reeve Foundation. Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://www.christopherreeve.org/todays-care/living-with-paralysis/rehabilitation/living-with-paralysis-rehabilitation-exoskeletons/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Font-Llagunes, J.M.; Lugrís, U.; Clos, D.; Alonso, F.J.; Cuadrado, J. Design, Control, and Pilot Study of a Lightweight and Modular Robotic Exoskeleton for Walking Assistance After Spinal Cord Injury. J. Mech. Robot. 2020, 12, 031008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhalka, A.; Areas, F.Z.d.S.; Meza, F.; Ochoa, C.; Driver, S.; Sikka, S.; Hamilton, R.; Goh, H.-T.; Callender, L.; Bennett, M.; et al. Dosing overground robotic gait training after Spinal Cord Injury: A randomized clinical trial protocol. Trials 2024, 25, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P. Chapter 37—Transcranial magnetic stimulation. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Levin, K.H., Chauvel, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780444640321000370 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

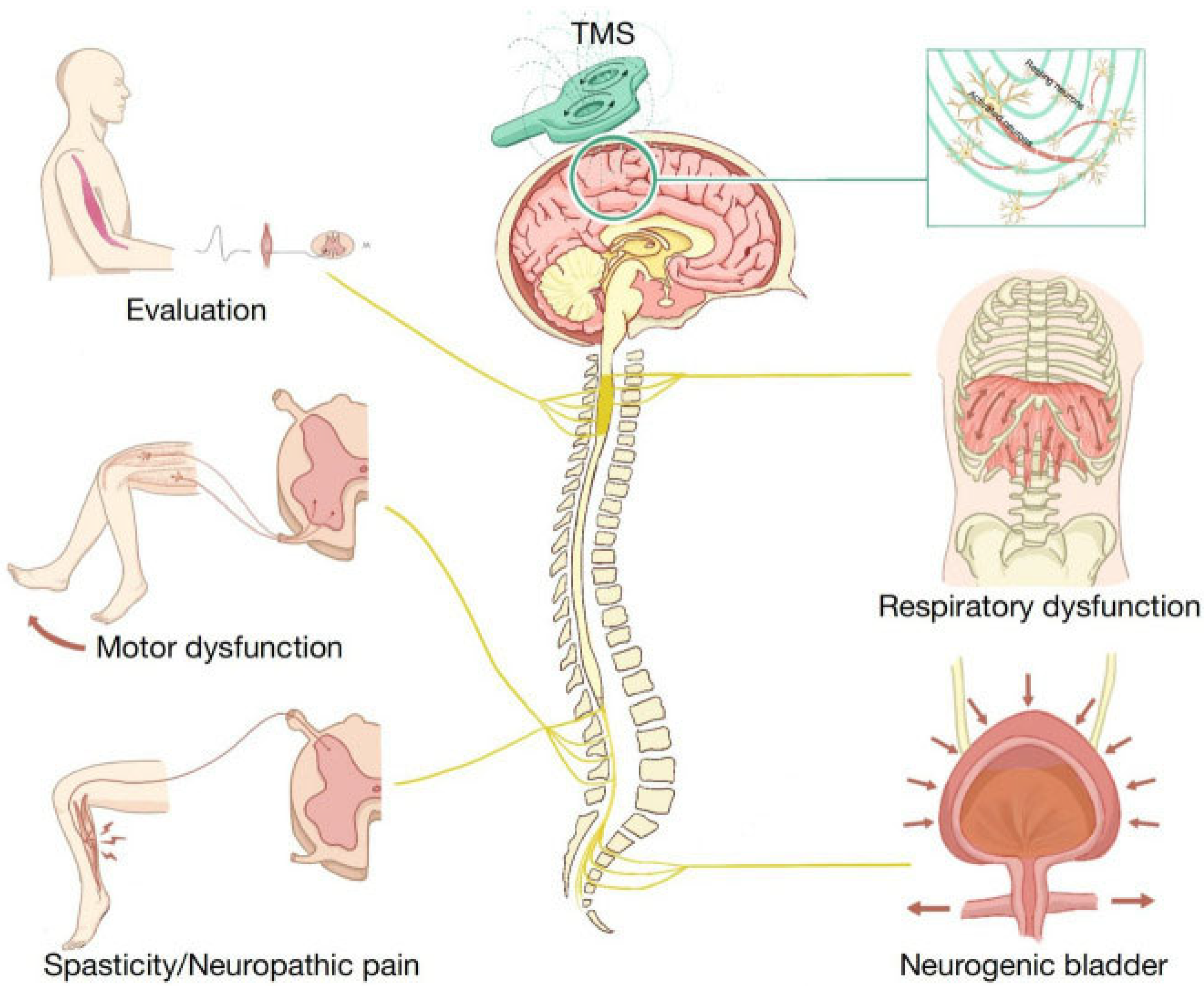

- Wang, Y.; Dong, T.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, L.; Xu, R.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Gai, X.; Qin, D. Research progress on the application of transcranial magnetic stimulation in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: A narrative review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1219590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, K.; Huber, J. The Role of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, Peripheral Electrotherapy, and Neurophysiology Tests for Managing Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Patel, S.; Khan, A.; Baamonde, A.D.; Mirallave-Pescador, A.; Chowdhury, Y.A.; Bell, D.; Malik, I.; Thomas, N.; Grahovac, G.; et al. NTMS in spinal cord injury: Current evidence, challenges and a future direction. Brain Spine 2025, 5, 104234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, F.; Shirahige, L.; Brito, R.; Lima, H.; Victor, J.; Sanchez, M.P.; Ilha, J.; Monte-Silva, K. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with body weight-supported treadmill training enhances independent walking of individuals with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Brain Topogr. 2024, 37, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Cabré, A.; Amengual, J.L.; Stengel, C.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Coubard, O.A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in basic and clinical neuroscience: A comprehensive review of fundamental principles and novel insights. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, K.; Hofstoetter, U.S.; Dzeladini, F.; Guertin, P.A.; Ijspeert, A. The Human Central Pattern Generator for locomotion: Does it exist and contribute to walking? Neurosci 2017, 23, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.A.; Casebeer, W.D.; Hein, A.M.; Judy, J.W.; Krotkov, E.P.; Laabs, T.L.; Manzo, J.E.; Pankratz, K.G.; Pratt, G.A.; Sanchez, J.C.; et al. DARPA-funded efforts in the development of novel brain–computer interface technologies. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 244, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARPA. Bridging the Gap (BG+): AI-Enabled Solutions for Spinal Cord Injury, YouTube. 2024. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyJcm-CfusI (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Liu, D.; Shan, Y.; Wei, P.; Li, W.; Xu, H.; Liang, F.; Liu, T.; Zhao, G.; Hong, B. Reclaiming hand functions after complete spinal cord injury with epidural brain-computer interface. medRXiv 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, T.; Sato, A.; Iwahashi, M.; Iramina, K. Using repetitive paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation for evaluation motor cortex excitability. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 125224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, S. 11 Challenges in Medical Device Design and How to Solve Them. iBrandStudio. 2023. Available online: https://ibrandstudio.com/articles/challenges-in-medical-device-design-how-to-solve (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Millar, J.; Long, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Haddadi, H. Towards low-energy adaptive personalization for resource-constrained devices. In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Machine Learning and Systems, Athens, Greece, 22 April 2024; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, P.; Chatterjea, S.; Das, K.; Havinga, P. Wireless Industrial Monitoring and control networks: The journey so far and the road ahead. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2012, 1, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, L.; Paul, L.; McFadyen, A.; Rafferty, D.; Moseley, O.; Lord, A.C.; Bowers, R.; Mattison, P. The clinical- and cost-effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation and ankle-foot orthoses for foot drop in multiple sclerosis: A multicentre randomized trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R.; Tang, N.; Shafawati, N.; Phan, P.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Chew, E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of robotic exoskeleton versus conventional physiotherapy for stroke rehabilitation in Singapore from A Health System Perspective. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e095269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumbhar, S.; Khadtare, S.; Zoman, S.; Rane, D.; Patel, V.; Bhinge, S. Regulatory complexities in Mdsap: Challenges and pathways for implantable medical device approval. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Medical Devices. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2021, 60, 117–176. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32017R0745 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

| SCI Treatment Methods | Author + Year | Mechanisms of Action | Targeted Injury Level | Stage of Development | Success Metrics/Validity | Long-Term Viability | Safety and Side Effects | Challenges/Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FES Systems-Freehand and IST-12 | Cleveland FES Centre, 1992; Ho et al., 2014 [12] | Implanted receiver-stimulator with 8–12 channels; uses shoulder elevation and myoelectric signals for hand grasp control. | Cervical SCI, upper limb function restoration | Second-generation implants under development | Enhanced grasp movement in upper limbs using myoelectric control | Second-generation device improved function but lacked full implantation. | Wires protruding from device negatively impact quality of life. | Not fully implanted; external wiring is cumbersome and reduces patient satisfaction. |

| FES Cycling | Griffin et al., 2009; Functional Electrical Stimulation Cycling for Spinal Cord Injury, 2012 [13] | Electrically stimulates motor neurons and muscle fibres via pulses; tracks muscle power output during cycling. | SCI with lower limb impairment | Commercially available with ongoing improvements | Improves motor and sensory neurons (ASIA scores); effectiveness at 30–60 Hz for 30-min sessions. | Regular use is required to prevent muscle deterioration. | High costs of equipment; time-consuming for patients. | Intrusive lifestyle demands; limited results if sessions are skipped. High equipment and implantation costs. |

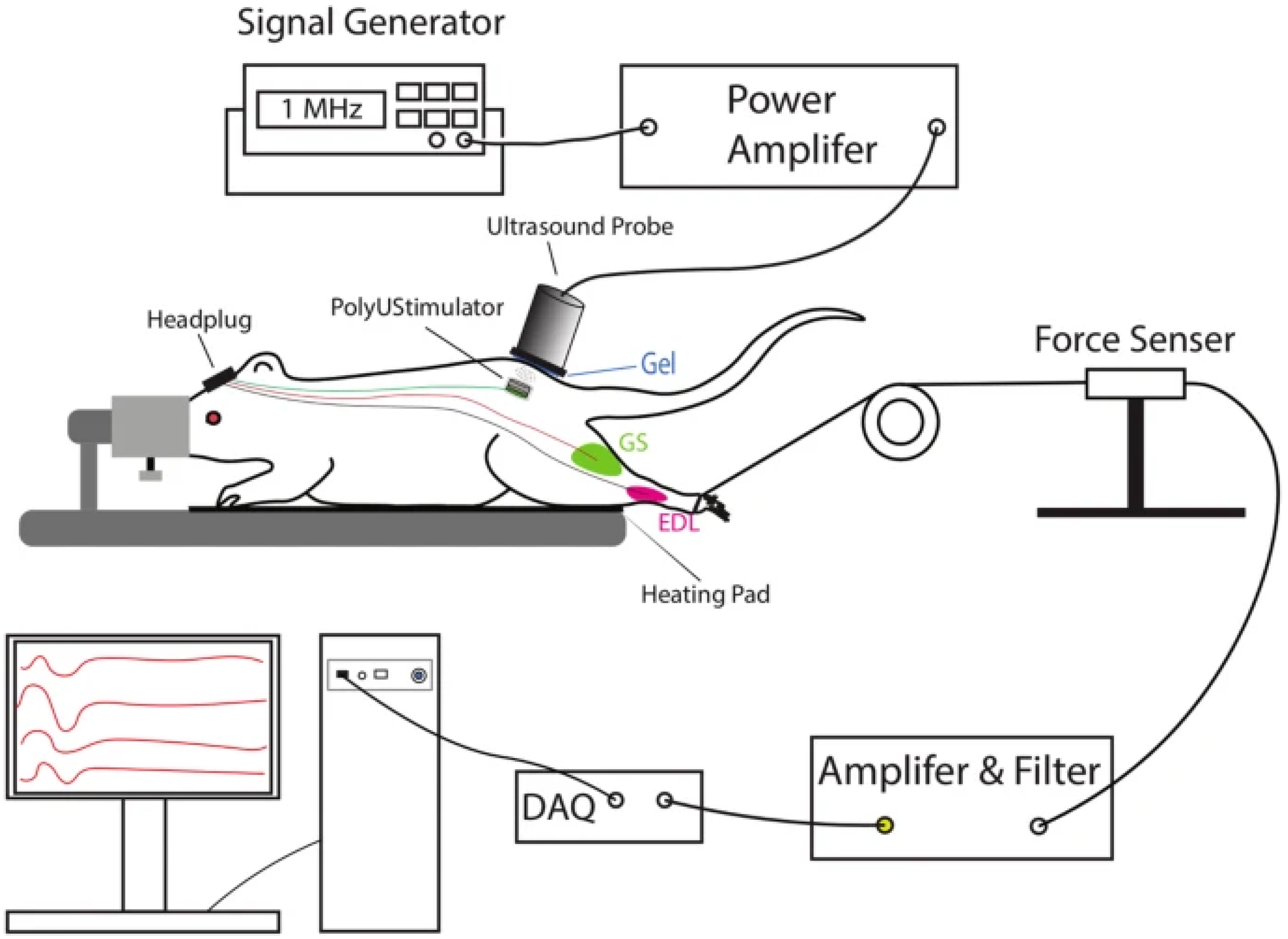

| Battery-freeUltrasonically Powered FES Device | Alam et al. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2019 [16] | Wireless stimulation using piezoelectric materials (e.g., PZT and BaTiO3) for targeted motor neuron restoration; powered via external ultrasound probe. | T7 spinal cord injuries (tested on rats) | Preclinical animal trials | Showed effective movement restoration in rat models; biocompatible materials used in implants. | Self-powered and wireless design reduces maintenance requirements. | Requires secondary implantation in the skull; risks displacement of ultrasonic probe. | Dependence on external probe; risks of inconsistent use. Mortality risks due to skull implantation. |

| Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) | Karamian et al. [17] | Electrical stimulation to activate muscles and promote neuroplasticity; implanted FES improves mobility and coordination; proposed wearable version integrates silver-threaded fabric | Varies by level of SCI; specific outcomes influenced by injury location and degree of paralysis. | Literature review with conceptual future directions. | FES highlighted as having highest neuroplastic benefit among stimulation; no original trial data included. | Implanted FES shows strong potential for long-term mobility and independence improvements. | No adverse effects reported, but no human trials for wearable version yet. | No experimental trials; individual variability due to SCI level: wearable FES requires future testing for efficacy and safety. |

| Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) using MyndMove | Balbinot et al. [20] | Application of FES to upper limb muscle via MyndMove device; uses pre-programmed protocols to stimulate muscle contraction and enhance motor control | Cervical SCI (upper extremity impairment) | Pilot study at tertiary SCI rehabilitation centre | Improvements in muscle strength, sustained voluntary contraction, and reduction in antagonist co-contraction; enhanced fine motor control. | Shows promise for restoring hand and arm function; not evaluated for long-term use or retention. | No major adverse effects reported, but small sample precludes full safety profile. | Small sample size limits generalisability: effectiveness may vary by SCI level; further trials needed for clinical translation. |

| Epidural Electrical Stimulation (EES) | Chalif et al.; Dimitrijevic et al., Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2024 [22] | Implantation of an epidural stimulator in the lumbar region to release electrical impulses, activating motor circuits and voluntary responses. CPGs enhance rhythmic locomotor patterns. | Lumbar SCI (lower limbs) | Clinical trials and patient studies | High success in restoring locomotor function; electrode positioning critical for effectiveness | Requires battery replacement every ~5 years; could support long-term functional improvement. | Risks of surgery include infection and human error. Implanted pulse generator may require replacement surgery every 5 years. | Battery life limitations requiring repeated surgeries; risks from electrode attachment and implantation of pulse generator impacting mortality. |

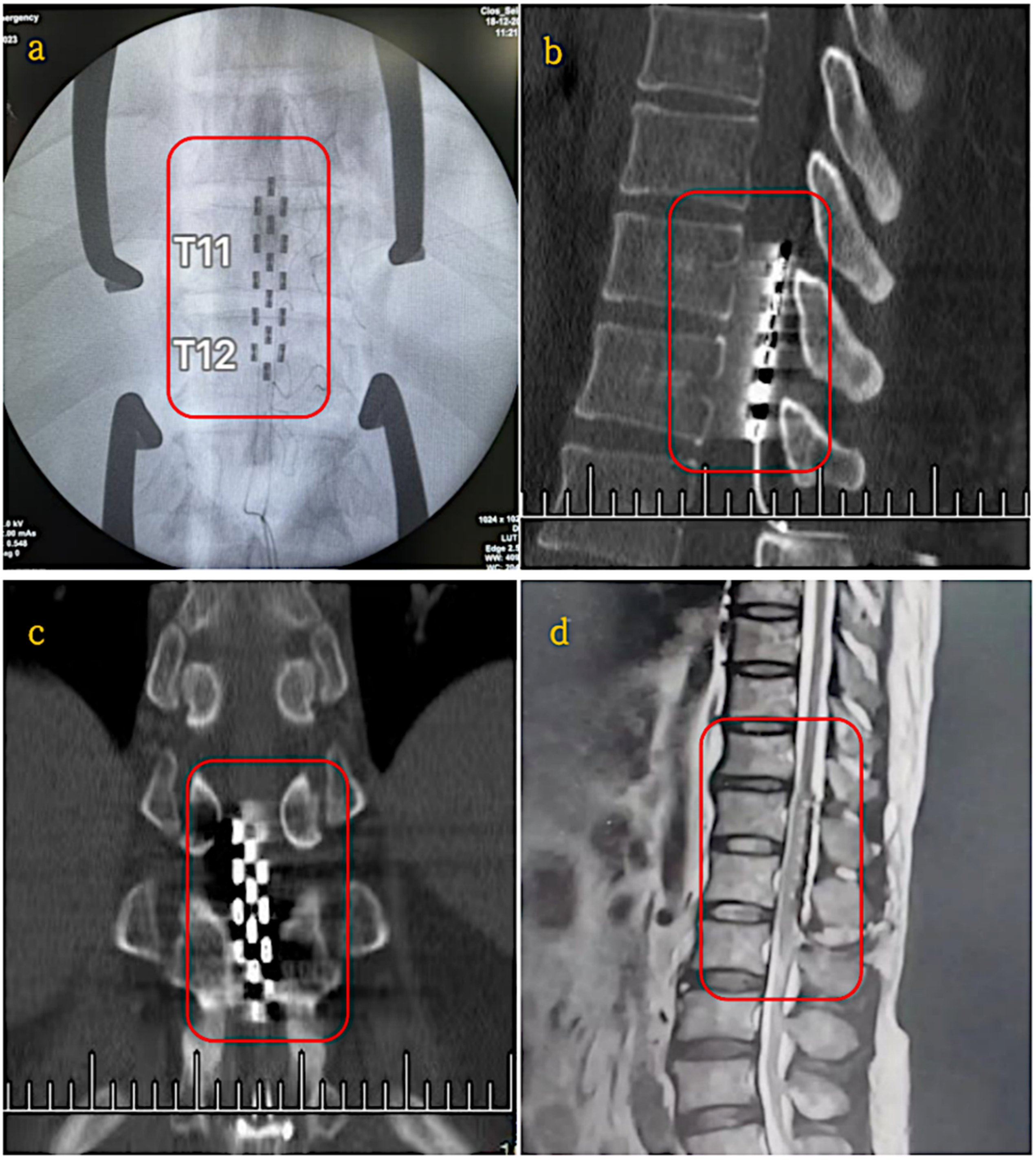

| Epidural Electrical Stimulation (EES) | Yihang Ren et al. [24] | Electrical stimulation via implanted electrodes to activate neural pathways and enhance motor function. | Incomplete SCI (Lumbar region, T11–T12) | Clinical Trial (19–25 month study period) | Significant improvements in sensory function (p < 0.01), muscle plasticity reductions (p < 0.0001), urinary functions in 6/11 patients and neuropathic pain relief in 4/5 patients. | Battery life limited to 5 years, requiring replacement surgery | Surgical risks include implantation complications, infection and device dependency. | Small sample size limits generalisability, effectiveness varies with SCI severity, requires wireless improvements to enhance usability. |

| Epidural Electrical Stimulation (EES) | Choi et al. [25] | Implanted electrodes on the dorsal lumbosacral dura matter deliver electrical impulses, activating spinal networks and voluntary motor responses; combined with training. | Chronic SCI | Systemic review of 64 studies with 306 patients | Improvements in locomotion (stepping, standing), cardiovascular and autonomic function; standing/walking in complete SCI patients. | Pulse generator enables long-term stimulation, yet battery life of 5 years limits extended viability without revision. | Device migration, infection risk, and post-implant complications observed; additional balance support often required. | Required surgery; battery needs replacement; variability in patient outcomes; need for standardisation and training parameters for optimal results. |

| SMART Spinal Implant | Barri et al., 2022; University of Pittsburgh Swansea, UK [31] | Self-aware metamaterial implant using triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) to convert body motion into energy and collect real-time data. | Spinal cord injuries and spinal fusion | Preclinical testing on synthetic and cadaveric spinal models | Successfully generated up to 9.2 V and 4.9 nA; monitored bone healing. Mechanical fatigue testing showed durability concerns (elastic modulus reduced from 1.76 MPa to 1.4 MPa; voltage dropped from 2.69 V to ~1 V after 40,000 cycles). | Self-powered, eliminating reliance on external power; continuous real-time monitoring; durability requires improved fabrication methods. | No direct safety issues noted in preclinical testing, but mechanical fatigue affects performance. | Cannot wirelessly log data; adaptation to patient-specific movements is limited. Larger human clinical trials and personalised designs are needed. |

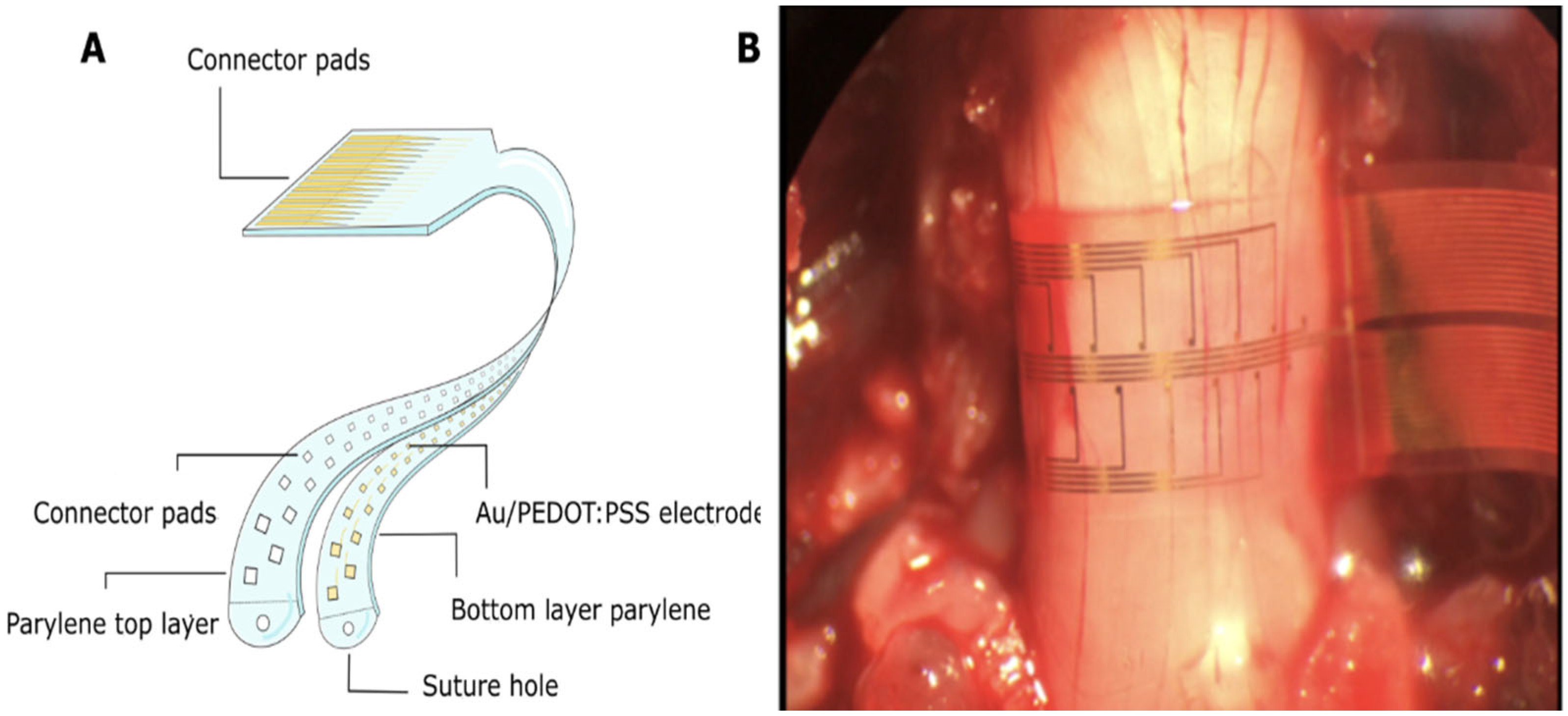

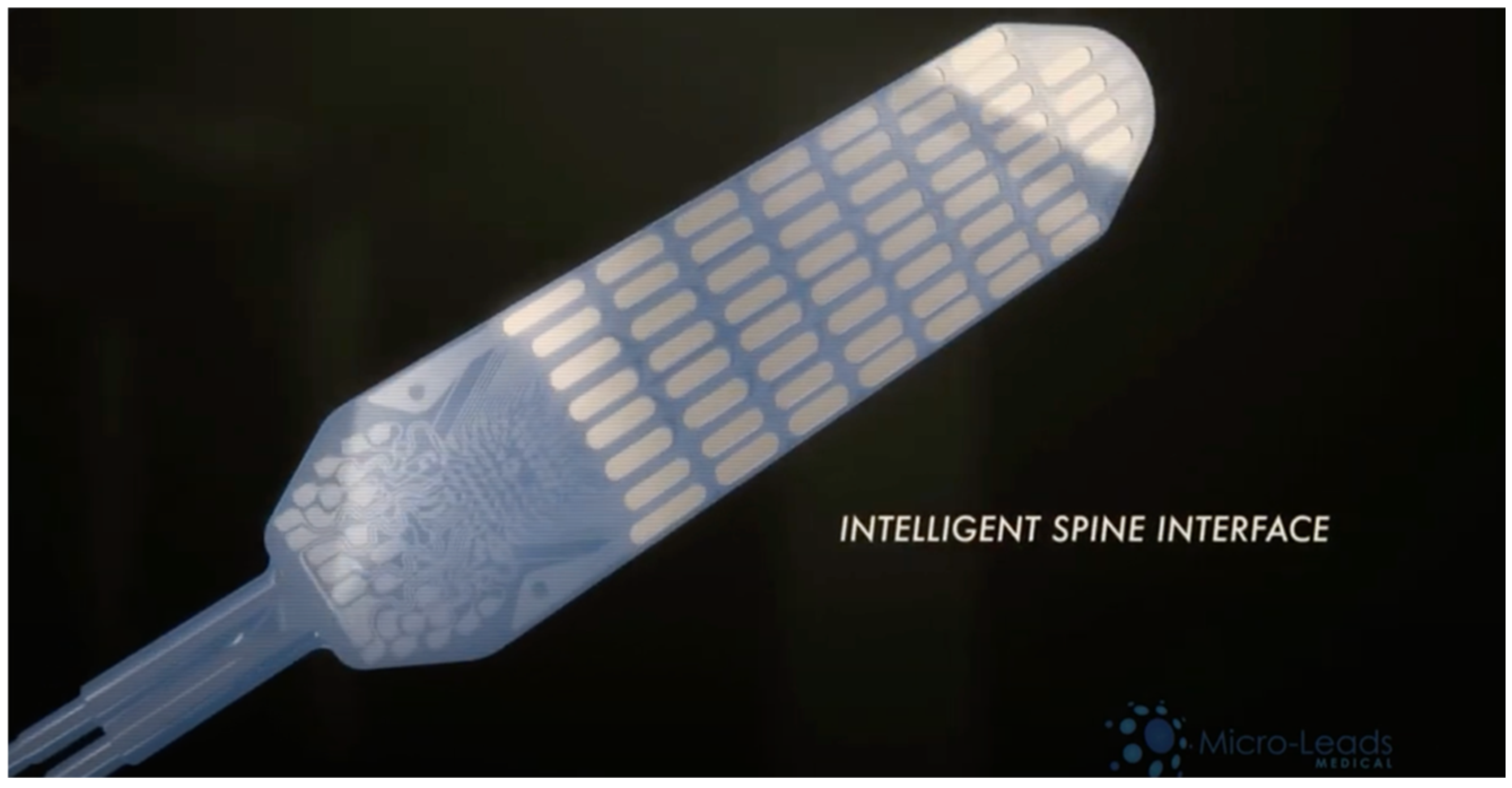

| SMART-Flexible Circumferential Spinal Cord Implant (i360) | Woodington et.al. University of Cambridge Research Team [32] | 32-electrode array providing 360-degree stimulation and signal recording; ventral stimulation enhances muscle activation | Tested on rats and human cadavers (potential for human trials) | Preclinical stage (No human clinical trials yet conducted) | Low latency observed in stimulating limb movement in rats, showing potential for human use. | Longevity and durability not yet tested; no mention of device power source. | No brain surgery required, reducing patient risk; unknown long term safety profile. | Lack of human trials, unknown long-term viability, potential wiring complexity, and no wireless data logging, limiting device adaptability. |

| Exoskeletons for SCI | Font-Llagunes et al., 2020; Spain, Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics [35] | Robotic orthoses with motor-harmonic drive actuation for knee flexion/extension; powered by backpack with computer boards, motor drives, and battery. | T11 spinal cord injury | Clinical testing on a female SCI patient | Increased gait symmetry and walking capability in patients with hip flexion control but no knee/ankle control. | Limited by bulky design; battery requires frequent charging, creating downtime when equipment is unavailable. | No significant side effects reported, but the bulkiness may negatively impact quality of life. | Bulky structure; limited transportability; requires frequent battery recharging, reducing continuous use and patient convenience. |

| Robotic Exoskeleton Gait Training (RGT) | Suhalka et al. [36] | Exoskeleton-assisted movement training to stimulate neuroplasticity and improve walking ability. | Motor-incomplete SCI (obtained within 6 moths of injury) | Clinical Trial (144 patients, 9-month assessment period) | High frequency RGT sessions led to significant improvements in walking ability, gait speed, independence, and neuroplasticity compared to control group. | Battery required charging downtime, limiting continuous use. | No major reported adverse effects, yet long-term impacts remain unknown | Small sample size, short term follow up, effectiveness in complete SCI unknown, battery limitations causing downtime. |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Katarzyna Leszczyńska and Juliusz Huber, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland, 2023 [39] | Non-invasive cortical stimulation through magnetic pulses; techniques include single-pulse TMS, paired-pulse TMS, and rTMS for motor cortex modulation. | Incomplete SCI (iSCI) | Evaluated for iSCI therapy through clinical trials. | Demonstrated potential for improved motor function through personalised stimulation of the motor cortex; used MagPro R30/X100 stimulators. | Not a long-term solution due to dependency on repeated sessions; quality of life may be impacted by treatment schedule. | No major safety concerns reported, but treatment requires careful intensity calibration to avoid exceeding RMT. | Limited success rate for long-term outcomes; dependency on frequent sessions; not effective for deeper brain regions without specialised coils. |

| Negative Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (nTMS) | Jung et al. Kings College London [40] | Uses magnetic stimulation to enhance neuroplasticity and muscle activation through various TMS protocols (PAS, iTBS, tsDCS). | Incomplete and traumatic SCI | Clinical research review (Evaluated 9 studies) | Majority of studies showed improvement in lower extremity motor score (LEMS), muscle activation patterns, and neuroplasticity. | Requires standardised protocols for clinical integration. | No major safety concerns reported, but effectiveness caries based on stimulation protocols. | Variability in protocols, short trial duration (4–8 weeks), and small participant groups (11–115) limit generalisability. |

| Repetitive TMS (rTMS) combined with BWSTT | Norgueira et al. [41] | Non-invasive rTMS modulates cortical excitability via magnetic pulses over primary motor cortex; BWSTT promotes gait cycle and initiates central pattern generator activation | Chronic incomplete SCI (iSCI), primarily cervical or thoracic | Pilot randomised clinical trial | Real rTMS group showed greater motor function and neuromuscular activation versus placebo group after 12 sessions. | Effects are temporary; dependent on session frequency and device power; no implant ensure no long term sustained impact. | No serious adverse effects reported; well tolerated by participants. | Small sample size; short study duration (4 weeks); non-implantable benefits require on going use; battery charging gaps may interrupt therapeutic gains. |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) | DARPA, USA, 2015 [45] | 64-channel electrode collects signals from the brain, processes them via machine learning, and relays them across spinal damage using electrodes. | SCI (general) | Prototype demonstrated; preclinical trials. | Demonstrated bidirectional flow of information across spinal cord damage; uses machine learning for motor/sensory decoding. | Not yet viable for long-term use due to external wires and lack of embedded wireless or battery-powered operation. | External wires pose infection risk and reduce usability; no significant safety concerns with current setup. | Requires battery-powered implant and wireless connection for greater usability; current design has external components, reducing practicality. |

| Brain Computer Interface (BCI) NEO Device | Liu et al. Tsinghua University and Xuanwu Hospital [46] | Wireless device (NEO) implanted in the brain; electrode adaptors record and stimulate neural signals via near-field coupling (power supply) and Bluetooth (signal transmission). | Complete C4 SCI | Early development stage (Single patient trial) | 100% object transfer success rate, high grasping score over 9-months, significant functional gains (ARAT improvement) | Battery-free design allows for longer usability, yet long-term stability remains untested. | Minimally invasive, yet still requires brain surgery, risk of infection and device migration. | Single patient trial limits generalisability, clinical implantation not yet feasible, further trials needed for validation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wallana, T.; Banitsas, K.; Balachandran, W. Reviewing Breakthroughs and Limitations of Implantable and External Medical Device Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15158488

Wallana T, Banitsas K, Balachandran W. Reviewing Breakthroughs and Limitations of Implantable and External Medical Device Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(15):8488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15158488

Chicago/Turabian StyleWallana, Tooba, Konstantinos Banitsas, and Wamadeva Balachandran. 2025. "Reviewing Breakthroughs and Limitations of Implantable and External Medical Device Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury" Applied Sciences 15, no. 15: 8488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15158488

APA StyleWallana, T., Banitsas, K., & Balachandran, W. (2025). Reviewing Breakthroughs and Limitations of Implantable and External Medical Device Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury. Applied Sciences, 15(15), 8488. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15158488