Abstract

Qualitative data analysis (QDA) tools are essential for extracting insights from complex datasets. This study investigates researchers’ perceptions of the usability, user experience (UX), mental workload, trust, task complexity, and emotional impact of three tools: Taguette 1.4.1 (a traditional QDA tool), ChatGPT (GPT-4, December 2023 version), and Gemini (formerly Google Bard, December 2023 version). Participants (N = 85), Master’s students from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science with prior experience in UX evaluations and familiarity with AI-based chatbots, performed sentiment analysis and data annotation tasks using these tools, enabling a comparative evaluation. The results show that AI tools were associated with lower cognitive effort and more positive emotional responses compared to Taguette, which caused higher frustration and workload, especially during cognitively demanding tasks. Among the tools, ChatGPT achieved the highest usability score (SUS = 79.03) and was rated positively for emotional engagement. Trust levels varied, with Taguette preferred for task accuracy and ChatGPT rated highest in user confidence. Despite these differences, all tools performed consistently in identifying qualitative patterns. These findings suggest that AI-driven tools can enhance researchers’ experiences in QDA while emphasizing the need to align tool selection with specific tasks and user preferences.

1. Introduction

In qualitative research, researchers typically use coding to label and group similar, non-numerical data to generate themes and concepts that allow for more manageable data analysis. Coding is a sophisticated process that involves reviewing the data, developing a set of codes that can accurately characterize each label, and classifying the data. Especially when dealing with large quantities of data, it is not surprising that researchers are looking for help in the field of digital technologies, where specialized software has been developed under the umbrella term qualitative data analysis (QDA) tools (e.g., [1,2]).

With the emergence of chatbots such as ChatGPT and Gemini (formerly named Google Bard) as a form of generative artificial intelligence (AI), qualitative data researchers have become interested in their usability in a coding process [3,4]. Therefore, researchers face the dilemma of choosing between specialized QDA tools and generative chatbots to find a solution that best fits the needs. To solve the dilemma, multiple material and non-material factors can influence the final decision. As qualitative researchers and educators, we were interested in finding an answer to the question of how, among many other factors, user experience (UX), usability, trust, affect, and mental load can be recognized as predictors of user perception when evaluating artificial intelligence-driven chatbots and traditional qualitative data analysis tools. Therefore, the strengths and weaknesses of chatbots compared to other digital technologies for the same tasks need to be carefully analyzed, including studies on the interaction between humans and computers.

The field of human-computer interaction (HCI) has been thoroughly researched, but studies combining HCI and chatbots, although numerous, are still at an early stage. What hinders practical researchers is also the fact that the functions and capacities that can influence the UX of chatbots change daily. Usability criteria such as effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction, for example, have been used to determine how successfully users can learn and use chatbots to achieve their goals and how satisfied users are with their use [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Comparative studies between tasks performed by chatbots and “traditional digital tools“ are even rarer, necessitating additional research [13].

Even though in the last five years, the number of publications in the field of evaluating the usability and UX of chatbots has started to increase, the existing literature reveals only a very limited number of studies that specifically analyze the usability of chatbots and the UX when using this type of technology for qualitative data analysis. This highlights the need for further research in this area. Our study aims to (1) identify and adapt standard measurement instruments for evaluating chatbots in the context of qualitative data analysis, and (2) evaluate and compare the usability and UX of chatbots for qualitative analysis and determine their (dis)advantage over non-AI-based tools. Based on previous research findings [5,7,9,10,11,12], our study aims to adapt and combine several different measurement instruments that will enable a more holistic analysis of the usability and UX of chatbots in the context of qualitative data analysis. At the same time, one of the goals of this study is to determine whether there are differences in usability and UX perceptions between chatbots and non-AI and natural language processing (NLP)-based QDA tools. This study may be regarded as piloting in HCI research by providing new insights into end users’ perceptions about the usability and UX of chatbots used in qualitative research. Additionally, based on the study’s results, validated measurement instruments provide the researchers with a tool for future research in this field.

The primary goal of the research is to analyze users’ perceptions of the usability and UX of AI-based and non-AI-based tools for qualitative data analysis. To accomplish this, the following research questions served as the foundation for our study design:

- RQ1.

- Are there significant differences in the usability and UX of chatbots and non-AI tools in the qualitative data analysis process?

- RQ2.

- Are there significant differences in trust, task difficulty, emotional affect evaluation, and mental workload experienced when using chatbots and non-AI tools in qualitative data analysis?

2. Backgrounds

2.1. Applications of AI-Powered Chatbots in Various Domains

Recent advances in AI, machine learning (ML) and NLP have contributed to the rapid rise in the popularity of chatbots [14]. Advanced AI models have recently emerged with a broader range of capabilities, including conversational AI and multi-modal functionalities, such as understanding text, images, and other media. AI systems like OpenAI’s GPT model [15], Gemini [16], and similar technologies make them suitable for tasks such as research, content generation, visual understanding, and complex decision-making, positioning them as multipurpose AI platforms.

ChatGPT [17], an example of a technology with high language production capacity, can be used in almost any real-world scenario, such as customer service and support, personal assistants, content creation, language translation, education and tutoring, creative writing and storytelling, mental health support, code writing and programming, healthcare and medical assistance, legal and compliance assistance, and medical imaging and radiology [3]. In programming, ChatGPT can help find errors and provide recommendations for code optimization, which can be helpful for programmers in understanding the errors and problems in the code [18]. A recent literature analysis revealed many potential benefits of using ChatGPT in education, including developing personalized and complex learning, specific teaching and learning activities, assessments, asynchronous communication, etc. [19]. Students find ChatGPT interesting, motivating, and helpful for study and work while also valuing its ease of use, human-like interface, well-structured responses, and clear explanations [20]. Chatbots can also be helpful in the classroom by giving students individualized practice materials, summaries, and explanations that can boost their performance and facilitate better learning opportunities [18,21]. Furthermore, students can enhance their critical thinking abilities, and gain more confidence by using ChatGPT in their studies [22]. ChatGPT has also become a valuable tool for research [23,24]. Using ChatGPT can improve (1) scientific writing with enhanced research equity and versatility, (2) dataset analysis efficiency, (3) code generation, (4) literature reviews, and (5) time efficiency in experimental design [25]. With little input, it can generate realistic writing indistinguishable from human-generated text and demonstrate critical thinking abilities to complete high-level cognitive tasks [26]. With proper precautions, ChatGPT can be a valuable tool for text analysis, increasing the effectiveness of theme analysis and providing more context for understanding qualitative data [24,27].

In summary, AI-powered chatbots have evolved into a kind of “technological Swiss Army knife”, providing user-friendly shortcuts to achieve satisfactory or even high-quality outcomes in certain contexts, though not universally. Like a Swiss Army knife, these tools are undeniably practical; however, this does not imply they can adequately replace specialized technologies (an example case study for mobile phones, see [28]). Thus, it is crucial not only to examine the differences in objective criteria, such as validity, reliability, and accuracy of responses between chatbots, humans, and other technologies but also to consider the UX, which is a distinctly subjective factor. The critical question highlighted here is whether people are willing to trade a higher-quality outcome, which demands effort and expertise in a specific technology, for a lesser-quality product provided by an automated system.

2.2. Qualitative Data Analysis Tools

Qualitative data analysis (QDA) software is a category of software, which has been developed since the 1980s and is designed to support qualitative research after the data gathering has been completed. The most common functions, included in QDA include assigning multiple codes to a single instance of data, cross-referencing the relationships among codes for pattern recognition, importing data as a means of comparing subgroups, tracking research ideas through data links and memos, and providing output in the form of exportable reports [29]. A plethora of commercial subscription-based QDA tools and packages exist, such as nVivo (https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/, accessed on 15 December 2024), ATLAS.ti (https://atlasti.com, accessed on 15 December 2024), Quirkos (https://www.quirkos.com, accessed on 15 December 2024), and MAXQDA (https://www.maxqda.com, accessed on 15 December 2024). On the other hand, only a few open-source software packages have been developed, and even fewer are maintained. Rampin and Rampin recognized that only four maintained open-sourced QDA tools and packages: Taguette (https://www.taguette.org, accessed on 15 December 2024), QualCoder (https://github.com/ccbogel/qualcoder, accessed on 15 December 2024), qcoder (https://docs.ropensci.org/qcoder/, accessed on 15 December 2024), and qdap (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/qdap/, accessed on 15 December 2024). The latter two are R-based and require advanced knowledge of end users [30]. QualCoder has a steep learning curve for first-time users. Taguette on the other hand offers a simple user experience also for the first time uses. It is available for MacOS and Windows, as a Docker image, and Python package and has reached more than 12 thousand downloads. The tool allows users to highlight sections of text and organize them in hierarchical tags, which can then be merged and recalled. It furthermore supports live user collaboration on a joint project [30]. The use of Taguette for qualitative data analysis has been widely reported in the existing body of literature (e.g., [31,32,33]).

2.3. Using Chatbots in Qualitative Research

AI has been applied in qualitative research since the 1980s, with early experiments focusing on developing expert systems that could understand natural language and was often used in professional settings like medical diagnostics to support or replace complex decision-making processes [34]. AI may have the power to disrupt the coding of data segments as a dominant paradigm for qualitative data analysis [35]. Although various AI-based tools can be used for qualitative data analysis, subscription fees are frequently required to utilize them entirely, making them unavailable to institutions and researchers with insufficient funding [24]. ChatGPT initially emerged as a language model. However, features like text shortening, interpretation, and detailed expression make it valuable for qualitative data analysis [36]. Using ChatGPT to analyse large quantities of qualitative data can significantly advance social studies and make it easier to incorporate AI-powered tools into standard social science research procedures [23].

ChatGPT is being investigated in various aspects and types of qualitative research, from transcription cleaning to theme generation through thematic analysis [24]. ChatGPT can accelerate the study of qualitative datasets, increase flexibility in comprehending and producing sociological knowledge, group codes into clusters, and help find patterns or connections [34]. ChatGPT is seen by qualitative researchers as a useful tool for thematic analysis, improving coding effectiveness, supporting preliminary data exploration, providing detailed quantitative insights, and supporting understanding by non-native speakers and non-experts [37]. Compared to conventional NLP techniques, which frequently call for in-depth programming expertise and complex coding processes, ChatGPT offers a strong substitute. Research outputs may be more effective and of higher quality because ChatGPT’s user-friendly, conversational interface streamlines the analytical process [38].

Thematic analysis, a qualitative research method for identifying and interpreting patterns in data, is one application that stands to benefit from tools like ChatGPT [24]. ChatGPT can improve current procedures, collect qualitative data through informal surveys, analyze and extract characteristics from massive volumes of unstructured data, provide valuable market intelligence, and save researchers time and effort by being able to recognize context and provide meaningful information [39].

A more recent study [38] examined ChatGPT’s ability to produce descriptive and thematically relevant codes, identify emerging patterns within a complex dataset, and conduct initial coding. This investigation demonstrated the model’s proficiency at navigating large volumes of textual data and offered a detailed perspective on thematic evolution across documents. When using ChatGPT for the qualitative analysis in systematic literature reviews, the tool can provide an overall 88% accuracy in article discarding and classification, where the results are also very close to the results given by experts [40].

Using ChatGPT in qualitative research provides many advantages, including increased productivity and time savings, enhanced data exploration and accuracy, reduction of bias, consistency and inter-rater reliability, generation of new insights, iterative and collaborative analysis, ability to identify patterns and trends in social data, facilitated natural language interaction with research participants, aided accurate behavior prediction [23]. By automating the coding and categorization process, researchers can concentrate on other crucial facets of their work [23]. However, it should be noted that when the coding is automated, the researcher is no longer as familiar with the input data that make up the concept, which can introduce the danger of oversimplification.

An explorative test of the suitability of ChatGPT for qualitative analysis [41] showed that ChatGPT is a valuable tool in qualitative analysis, provided that the researcher can ask appropriate questions (prompts). De Paoli investigated if ChatGPT can be used to perform thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with a focus on using the analysis results to write user personas. The study showed that the model could build basic user personas with acceptable quality, deriving them from themes and that the model can generate ideas for user personas [42]. Further investigations verified that conducting an inductive thematic analysis with large language models is feasible and provides a high level of validity [43]. The quality and timeliness of turning audio files into readable text are among the main inefficiencies in qualitative research. However, an existing study demonstrated that ChatGPT can be an efficient tool for qualitative researchers who must clean up interview transcriptions [44].

Although ChatGPT seems to be the most highlighted representative of AI-based chatbots, other emerging chatbots, such as Gemini and Copilot, are increasingly gaining traction as supporters in qualitative analysis. A study conducting health-related research interviews with human responders, ChatGPT and Gemini (Bard) concluded that Gemini exhibited less interpersonal variation than ChatGPT and human respondents [45]. Slotnick and Boeing studied the use of generative AI, focusing on Gemini and ChatGPT, to enhance qualitative research within higher education assessment. The results showed that Gemini has been less accommodating to text file conversions, though it could provide references in its responses (compared to ChatGPT, which gave general suggestions on how to find literature), and by default provided fewer recommendations in prompts [46].

Researchers have also raised several issues or difficulties with employing AI-based chatbots for qualitative research in the currently available literature. These challenges include the potential for missing subtle emotional cues or implicit themes (especially in human-centric research) [24], the fear of losing theoretical development [23], the reluctance of qualitative researchers to use AI because it conflicts with critical research approaches [34], the conflict between human judgment and AI in qualitative research (e.g., reflexivity and interpretation) [34], AI as a complementary tool (AI should assist but not replace human analysis) [24], non-reproducible results in qualitative analysis (AI variability) [34], AI lacks the ability to experience the world firsthand and interpret it through human interaction [24], concerns over the use of AI for coding sensitive data (restrictions on use with confidential transcripts) [24], and the lack of the researcher’s creativity and reflexivity as essential elements in qualitative data analysis [34].

2.4. Research on Chatbot Usability and User Experience

In the existing literature, a steep growth is observed in the number of publications evaluating the usability and UX of chatbot solutions (see Table 1). The first studies examining the value of contemporary chatbot solutions were published in 2019 and 2020. However, it is clear that, since 2021, interest in chatbot UX and usability research increased significantly. The body of literature currently provides a rich collection of scientific works investigating various aspects of usability, UX, and factors that significantly influence the acceptance and use of chatbot solutions in different domains or fields.

As can be seen in Table 1, a considerable part of the study related to the UX and usability of chatbots has been carried out in the health domain (e.g., [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]) and related areas such as mental health (e.g., [10,54,55,56,57]), digital health [58], and well-being [59]. Several chatbot UX and usability studies have also been conducted in the context of education (e.g., [14,51,60,61]) and higher education [62]. We can also find studies that evaluated chatbot solutions in other domains such as e-retailing [63], customer support services [8], customer relationship management [11], tourism [13], research in pharmacy [64], and others. Mulia, for example, evaluated the usability and users’ satisfaction when using ChatGPT for text generation [65].

Table 1.

Existing Chatbot UX and Usability Research.

Table 1.

Existing Chatbot UX and Usability Research.

| Study | Year | Focus | Chatbot | Domain | Metrics, Instruments | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | 2019 | Usability | iHelpr | Mental health | Chatbottest, SUS | SUS = 88.2 |

| [59] | 2019 | Usability | Weight-Mentor | Health care, wellbeing | Ease of task completion, task performance, usability errors | High Usability Scores |

| [47] | 2020 | UX | Chatbot-based questionnaire | Health care | UEQ | NA |

| [10] | 2020 | UX | Mood chatbot | Mental health | I-PANAS-SF, Affect Grid | NA |

| [63] | 2021 | Usability and adoption | Customer experience chatbot | E-retailing | Responsiveness, customer experience, customer satisfaction, and personality | Positive relationship between online experience and satisfaction |

| [55] | 2021 | UX | SERMO | Mental health | UEQ | Positive attractiveness, neutral hedonic qualities |

| [8] | 2021 | UX and HCI | Customer service chatbot | Customer service | PARADISE | NA |

| [48] | 2021 | Usability | MYA | Health | CUQ | NA |

| [60] | 2021 | UX and usability | Buddy Bot | Education | UEQ, SUS | NA |

| [64] | 2021 | UX and usability | Atreya | Chemistry, pharmacology | SUS, CUQ, UEQ | SUS = 80.7; CUQ = 78.14; UEQ = 2.379 |

| [49] | 2021 | Usability and acceptability | Ida | Health | SUS | SUS = 61.6 |

| [56] | 2022 | Usability, trust | ChatPal | Mental health | SUS, CUQ | SUS = 64.3; CUQ = 65 |

| [11] | 2022 | UX and usability | Finnair Messenger | CRM | BUS-15, UMUX-LITE | BUS-15 strongly correlates with UMUX-LITE |

| [61] | 2022 | Usability | myHardware | Education | SUS | SUS = 61.03 |

| [50] | 2022 | Usability | MYA | Health | CUQ | CUQ = 60.2 |

| [13] | 2022 | HCI and user satisfaction | Reservation Chatbot | Tourism | Perceived autonomy, perceived competence, cognitive load, performance satisfaction, and system satisfaction | NA |

| [9] | 2022 | Usability, usefulness, satisfaction, ease of use | Alex | Health | SUS, USE questionnaire | SUS scores between 75.0 and 85.5 |

| [51] | 2023 | Usability | Saytù Hemophilie | Health, Education | SUS | SUS = 81.7 |

| [12] | 2023 | UX and usability | Ten chatbots | Various | BUS-11 and UMUX-Lite | NA |

| [52] | 2023 | UX and usability | Ana | Health | Ease of use, usefulness, and satisfaction | Usefulness = 4.57; ease of use = 4.44; satisfaction = 4.38 |

| [57] | 2023 | UX, satisfaction, acceptability | TESS | Mental Health | UEQ, satisfaction questionnaire | High acceptability level |

| [66] | 2023 | Usability | Medicagent | Health | SUS | SUS = 78.8 |

| [14] | 2023 | Usability | Aswaja | Education | SUS | SUS = 64.0 |

| [65] | 2023 | Usability and user satisfaction | ChatGPT | Text Generating | SUS | SUS = 67.4 |

| [53] | 2023 | Usability | Vira | Health | CUQ | CUQ = 70.2 |

| [62] | 2024 | UX and usability | CAI Bing Chat | Higher education | Perceived usefulness, SUS, learnability, system reliability | Positive scores for usability |

| [58] | 2024 | Usefulness | Flapbot | Digital health | SUS | SUS = 68.0 |

Note: BUS, Bot Usability Scale; CUQ, Chatbot Usability Questionnaire; I-PANAS-SF, International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short Form; PARADISE, PARAdigm for DIalogue System Evaluation; SUS, System Usability Scale; UMUX-LITE, Usability Metric for User Experience LITE; UEQ, User Experience Questionnaire; USE, Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use.

Existing research on chatbot usability and UX covers a broad spectrum of applications, with studies examining factors like task completion, user satisfaction, effectiveness, and specific usability metrics such as the System Usability Scale (SUS) (e.g., [9,14,49,51,54,56,58,60,61,62,64,65,66]), the Chatbot Usability Questionnaire (CUQ) (e.g., [48,50,53,56,64]), the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) (e.g., [47,55,57,60,64]). The Usability Metric for User Experience LITE (UMUX-LITE) [67] offers a quick and reliable measure of usability with a strong correlation to the SUS. Borsci et al. validated the UMUX-LITE tool extensively in the context of chatbot usability, demonstrating its applicability and robustness for evaluating conversational systems and highlighting its advantages as a streamlined alternative to traditional usability scales [11,12]. We found only one study in which the authors built a measurement instrument based on the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Short-Form (I-PANAS-SF) [10]. Studies evaluating factors that affect chatbot UX and usability also include other metrics, such as attractiveness [55], cognitive load [13], customer satisfaction [63], ease of completing tasks [59], ease of use [9,52], learnability [62], perceived autonomy [13], perceived competence [13], satisfaction with operation [13], responsiveness [63], satisfaction with the system [13], satisfaction [57], system reliability [62], task performance [59], utility [9,52,62], utility errors [59], and others.

Existing research that used the SUS instrument for usability evaluation provided diverse results. Although not all articles reported final SUS scores (on a 0 to 100 scale), the analysis of SUS scores published in the existing literature reveals that the usability of chatbots varies significantly between the lowest score of 60.03 (for the chatbot myHardware [61] that is used in education) and the highest score of 88.2 (for the chatbot iHelpr used in mental health). For example, the WeightMentor chatbot for weight loss maintenance showed high ease of task completion and positive usability scores despite some usability errors [59]. Similarly, the mental health chatbot iHelpr received a high SUS score of 88.2, indicating high usability compared to industry standards [54]. In a healthcare setting, the chatbot-based questionnaire at a preoperative clinic was preferred over traditional computer questionnaires, even though completion times were similar [47]. Studies like that of ChatPal, a mental health chatbot, highlighted the chatbot’s usability (SUS = 64.3) and user satisfaction, showing a strong positive correlation between these metrics [56]. In the education domain, the myHardware chatbot received a SUS score of 61.0, indicating moderate usability [13], while the Aswaja chatbot for promoting Islamic values among youth scored 64.0 on the SUS, suggesting room for improvement [14]. Additionally, the Atreya chatbot for accessing the ChEMBL database in chemistry received a high SUS score of 80.7, demonstrating excellent usability in an academic research context [64]. The development of new evaluation tools like BUS-15 and BUS-11 for assessing chatbot-specific UX shows advancements in addressing the nuances of conversational agents, including aspects like conversational efficiency and accessibility [11,12].

The UEQ instrument has been used in chatbot research to evaluate UX, capturing both pragmatic and hedonic aspects of interaction. For example, in the evaluation of the SERMO chatbot, which applies cognitive behavioral therapy for emotional management, the UEQ highlighted positive user feedback on efficiency, perspicuity, and attractiveness while providing neutral scores for hedonic qualities like stimulation and novelty [55]. Similarly, the Differ chatbot, designed to facilitate student community building, was assessed using the UEQ, which revealed that although the overall UX was slightly above average, there was room for improvement in the areas of novelty and stimulation [60]. Additionally, a study on a COVID-19 telehealth chatbot by Chagas et al. used the UEQ to assess various facets of the UX, with the chatbot receiving high ratings for ease of use, user satisfaction, and the likelihood of being recommended to others [52]. These studies demonstrate that the UEQ is a valuable tool for providing a holistic view of UX by evaluating chatbot interactions’ functional and emotional characteristics.

Existing literature lacks standardized tools for evaluating user satisfaction with chatbots. Therefore, Borsci et al. developed a new instrument—the Bot Usability Scale (BUS-15), that evaluates chatbot-related aspects like conversational efficiency and accessibility, which are missing in traditional usability evaluation instruments. Their study demonstrated a strong reliability of the BUS-15 and a sound correlation with the UMUX-LITE instrument, making it a significant advancement for chatbot-specific usability assessment. The correlation was evaluated on a sample of 372 surveys; a strong and significant correlation was observed between the overall BUS-15 scale and UMUX-LITE. Bayesian Exploratory Factor Analysis revealed five factors of BUS-15 questionnaire: perceived accessibility to chatbot functions, perceived quality of chatbot functions, perceived quality of conversation and information provided, perceived privacy and security, and time response) [11]. In chatbot usage, both pragmatic (e.g., efficient assistance) and hedonic (e.g., entertainment value) factors can significantly impact UX with chatbots. Younger users may prioritize hedonic aspects, such as the chatbot’s entertainment value, while older users focus more on pragmatic elements, like efficiency and task performance. This indicates that user preferences for chatbot features can vary significantly based on demographic factors [8].

Several domain-specific chatbots that address specific needs have been studied recently, and the results reveal the increasing complexity of conversational agent-specific usability and UX research, creating new usability tools, and investigating chatbots in specialized fields where UX might have significant practical implications. For example, the Medicagent chatbot for hypertension self-management received a 78.8 SUS score, indicating that people managing chronic health issues can find it useful [66]. The Flapbot chatbot is an additional domain-specific tool that facilitates free-flap monitoring in the field of digital health. The study on Flapbot highlighted its average usability score of 68, with strong content validity ratings, by combining the SUS and content validity indices [58]. This shows that researchers are using more thorough evaluations in addition to typical usability criteria to make sure chatbots suit specific requirements (e.g., medical requirements in the case of the Flapbot).

2.5. Research on Chatbot Trust, Task Difficulty, Emotional Affect Evaluation and Mental Workload

User trust measurement in intelligent chatbots has already been observed in prior related work due to its central role in chatbot adoption and interaction outcomes through a single, universally accepted method for measuring trust has not yet been established. A study that included 607 respondents and their adoption of ChatGPT recognized trust as a critical component of chatbot adoption. It also highlighted the challenge of excessive user trust in chatbot responses in the health care domain [68]. Trust has been measured with various constructs in the existing body of research. A recent study conducted by Lee and Cha [69] focused on analyzing perceived trust and transparency in ChatGPT. The results indicated that predictability acts as a bridge between how transparent the AI system is and the trust users develop in it. Transparency (via accuracy and clarity) has been observed to positively influence trust (by reducing distrust in users). A meta study on trust in the general AI domain has confirmed a lack of research observing trust in AI systems. The study identified characteristics and abilities as factors in human trust and performance and attributes as factors in AI systems while also mentioning contextual factors, where team and task impact were recognized [70]. A previously mentioned study on mental health and the well-being chatbot [56] utilized a simpler measurement of trust score, a single question on a five-point Likert scale for each task (where 1 = very low level of trust, 5 = very high level of trust). All five responses were then summed for each user.

Task difficulty is a crucial metric for understanding the impact of different tools on the perception of a task’s execution difficulty. A previous study on healthcare chatbots [59] has used Single Ease Question as a method for gathering data on users’ prediction of the task difficulty (“On a scale of 1 to 7, how easy do you think it will be to complete this task?”) and for measuring it post-hoc (“On a scale of 1 to 7, how easy was it to complete this task?”). Use of ChatGPT in asynchronous video interviews showed that users perceived job interview task difficulty as lower on a seven-scale Likert scale when they used verbatim ChatGPT answers () or when they personalized ChatGPT responses (), compared to the group that had no access to it (). The measurement of task difficulty is not limited to perceived difficulty. A more objective approach to measuring difficulty based on the percentage of users that have successfully completed the task has also been reported [56].

Emotional Affect Evaluation examines users’ emotional responses and affective experiences during interactions with AI chatbots. A recent study compared responses in evoked sentiment in users when presented with ChatGPT-generated narratives and real tweets. The study observed 44 narratives about birth, death, hiring, and firing. The comparison of emotional affect was conducted using a full PANAS questionnaire. Narratives generated with ChatGPT reached higher sentimental values (in 72% of the observed cases) than tweets on the eleven PANAS groups. Sentiment levels of the content, generated with ChatGPT were statistically indiscernible from tweets only in about 9% of the cases [71]. Emotional affect can also be probed in semi-structured interviews, as shown in a study on users’ emotional reactions when using ChatGPT for the task of generating academic feedback on students’ (own) research proposals. It indicated two main emotional reactions: satisfaction, which was mostly related to tools paraphrasing and translation abilities, while dissatisfaction was observed with the received suggestions on mechanics [72].

Mental Workload assesses cognitive demands placed on users during interactions with AI chatbots. This dimension was analyzed as cognitive load in the previously mentioned study comparing chatbot interfaces to menu-based ones, where researchers reported higher cognitive load for the former systems [13]. A recent survey investigated human factors’ (including perceived workload, performance expectancy, and satisfaction) influence on trust in ChatGPT. Researchers reported a negative correlation between perceived workload and users’ trust level in the systems, as well as between workload and user satisfaction [73]. A limited set of NASA-TLX questionnaires has been used for measuring perceived workload in this study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

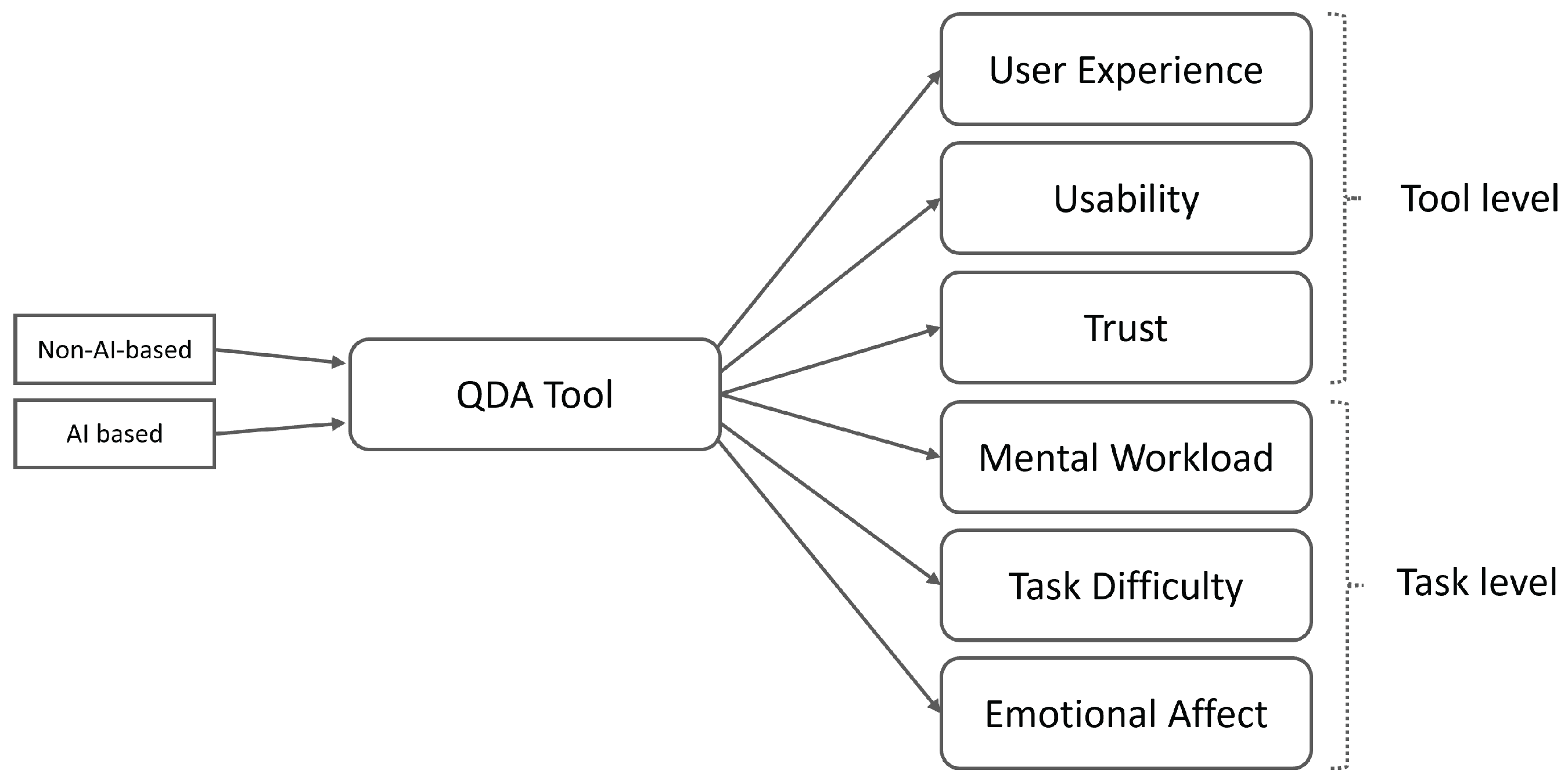

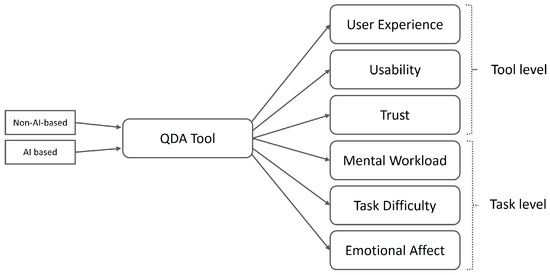

This study’s main goal was to compare how users’ perceived usability, ease of use, UX, mental effort, and trust between non-AI and AI-based tools differ when conducting qualitative data analysis. Simultaneously, we aimed to understand if user perceptions varied according to the kind of chatbot tool utilized. The basic conceptual model of the main variables that we aimed to investigate, evaluate, and compare with our research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of research.

This study used the Taguette tool as an example of a tool that does not use AI for qualitative data analysis. Taguette is a free QA tool that can be used to analyze qualitative data such as interview transcripts, survey responses, and open-ended survey questions by encoding different text data segments and allowing multiple tagging in text segments, making it easier to identify patterns or themes [20]. As examples of two AI-based tools in our study, we chose ChatGPT (version 3.5) and Gemini, which also proved to be tools with high accuracy, comprehensiveness, and self-correction capabilities [74].

The study’s main objective was to evaluate user perception of the observed AI-based chatbots and non-AI-based tools in the context of qualitative analysis. We focused primarily on the users’ perceptions of using a specific tool for qualitative data analysis. The goal was also to establish measurement instruments to capture quantitative data and compare users’ perceptions of different tools.

Participants in this research were set in the role of UX researchers and tasked with a qualitative evaluation using individual tools. Since the goal was not to compare tools directly, we provided users with different sets of qualitative data obtained in preliminary research about the content, UX, and structure of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics, University of Maribor website. The role of the participants in this study was to analyze the obtained qualitative data and to present both positive and negative aspects of the faculty’s website content, UX, and structure quality.

Participants were presented with three separate text documents (content.txt, ux.txt, and structure.txt), each containing 100 user responses. These responses were collected through an online survey designed to evaluate the faculty’s website https://feri.um.si/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2024). In the survey, 100 users, including students and faculty members (professors, teaching assistants, and others), answered three open-ended questions addressing weaknesses in the website’s content, user experience, and structure. The data gathered as part of a prior user study, served as the basis for the qualitative analysis conducted in our experiments.

Responses were mostly short and presented in separate lines. Examples of the responses included “Too much content at once”, “I find the content OK, as it is related to the study or fields of study”, “A lot of irrelevant content. The front page should not contain news/announcements", "Too few colours, page looks monochrome”, “Maybe someone can’t find what they’re looking for because they can’t find the relevant subcontent”, “I didn’t notice any shortcomings”, and so on. Data was organized into three separate documents to prevent participants from becoming overly familiar with a single dataset, which could have influenced their perception across the tools. By introducing a fresh dataset for each tool, we ensured that any differences in users’ perceptions were more reflective of the tool than prior knowledge of the data. The first file, content.txt, contained answers to questions concerning the quality of the content provided on the faculty website. The second file, ux.txt, included a set of answers to the open-coded question concerning the UX quality of the faculty’s website. Finally, the third file, structure.txt, included answers about user’s perceptions of the website’s structure quality.

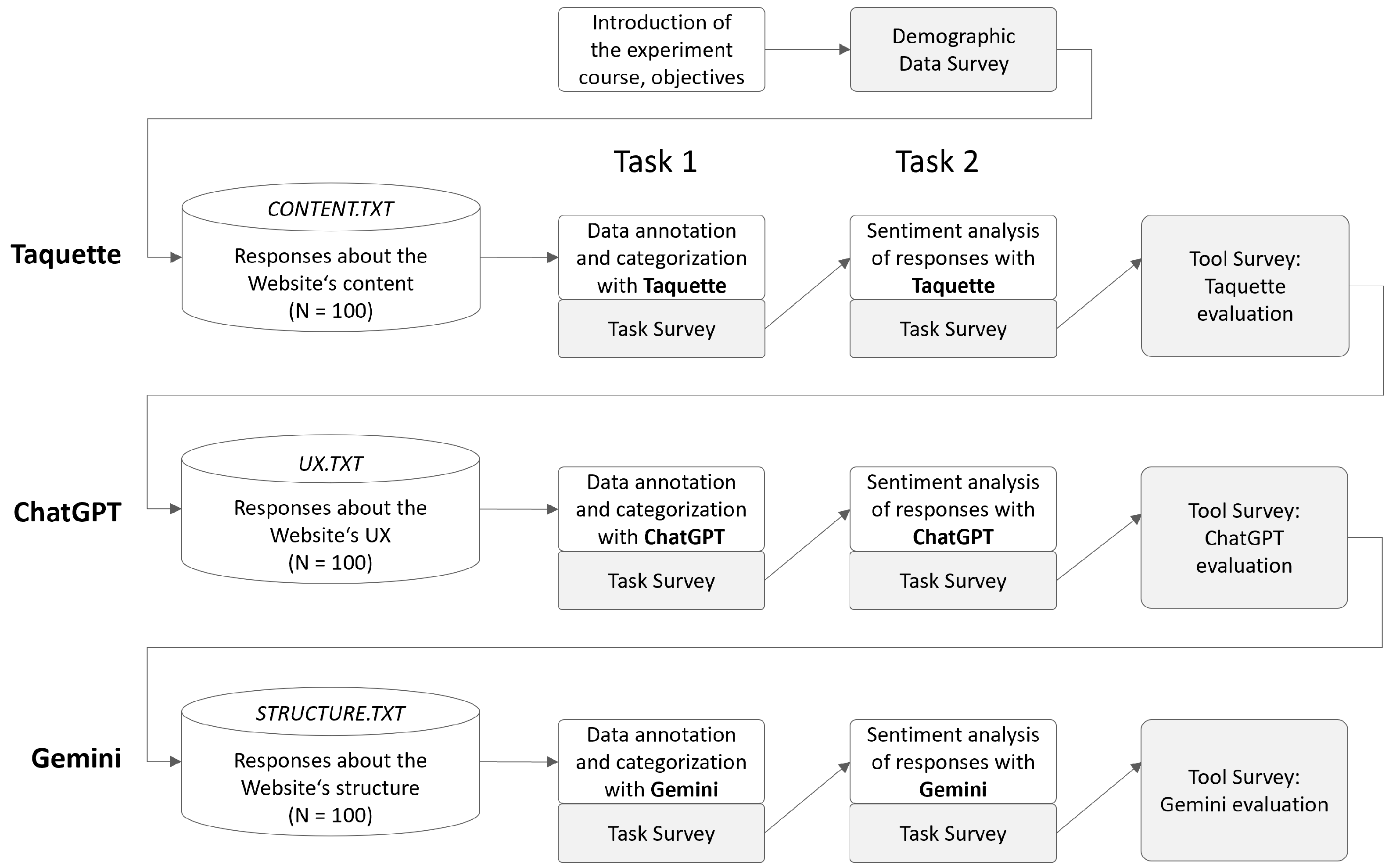

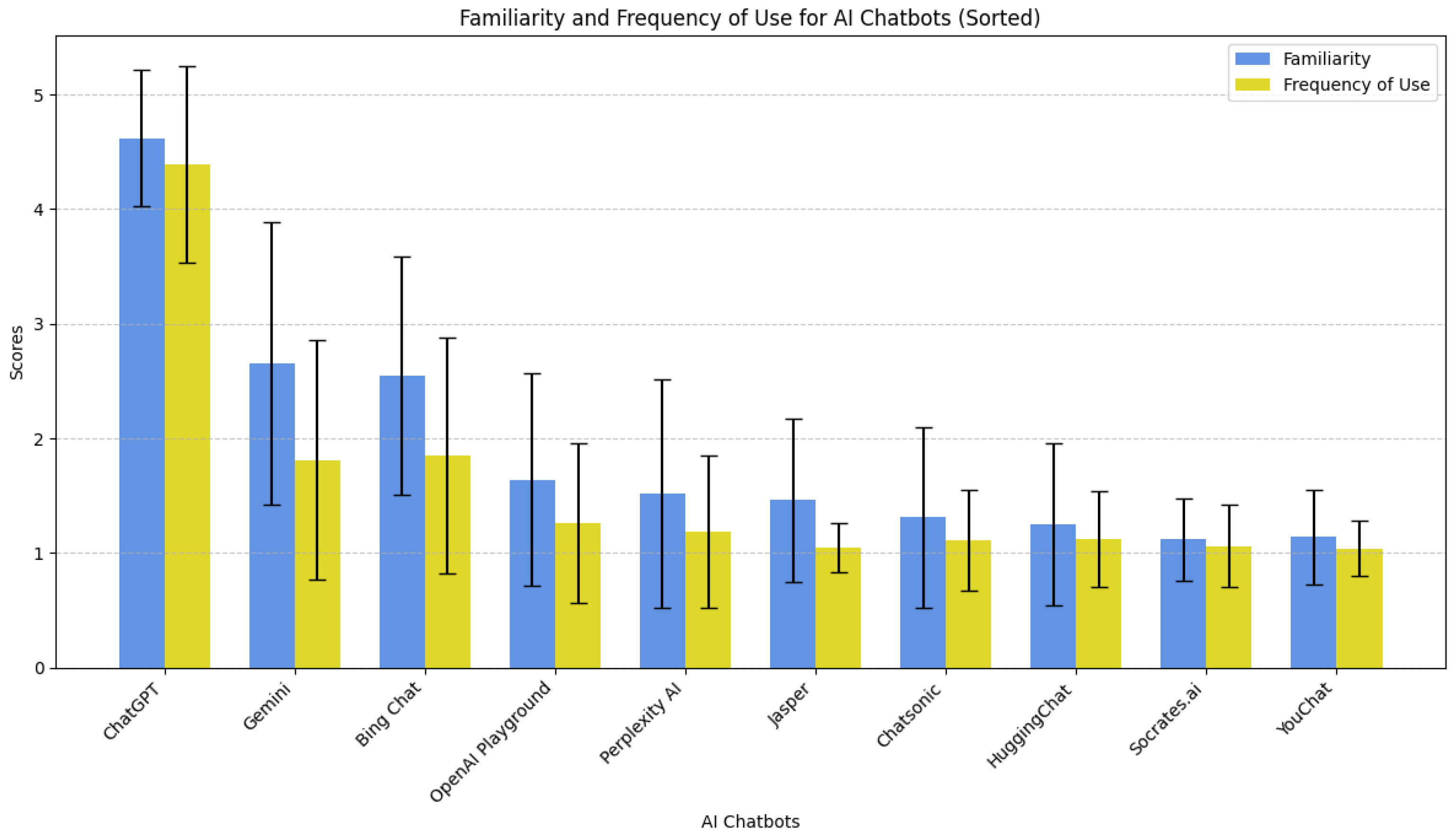

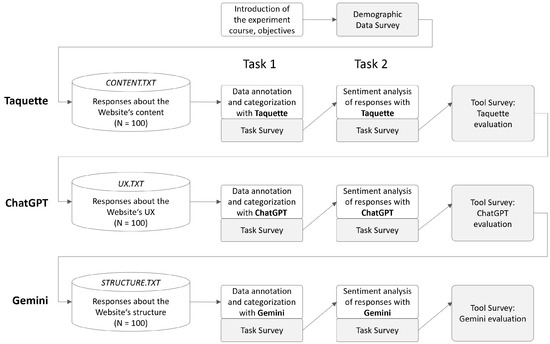

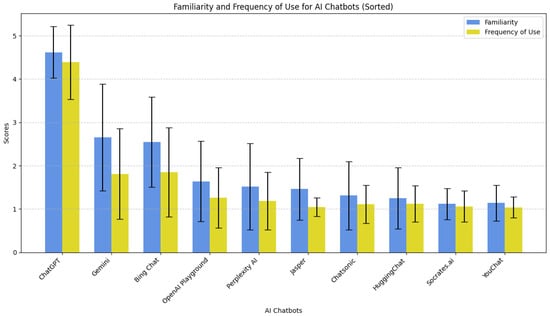

This study’s process involved several steps that included practical tasks as presented in Figure 2. In the beginning, we presented the basic purpose and goals of the experiment to the participants and briefly explained the basic steps (without a detailed explanation of the individual tasks). In this initial step, the participants signed a statement agreeing to participate in the research and use the data for further research. A short survey followed the introduction step, the aim of which was to collect basic demographic information about the participants of the experiment. This included information on participants gender, tool familiarity level and frequency of AI chatbot use. User familiarity with AI tools was assessed for ten of the most common AI-based chatbots available on the market at the time of the study (i.e., ChatGPT, Gemini, Bing Chat, OpenAI Playground, Jasper, Perplexity AI, HuggingChat, Chatsonic, YouChat, Socrates.ai). Five-point Likert scale with answers ranging from 1—Not familiar at all to 5—Very familiar was used. The frequency of the AI tool used was assessed on a similar five-point Likert scale (1—Never, 2—Very rarely, 3—Occasionally, 4—Frequently, 5—Very frequently). All aforementioned demographic data was self-reported. While user familiarity with a broader range of chatbots was assessed to contextualize participant experience, ChatGPT and Gemini were specifically selected for experimental tasks due to their advanced functionalities, alignment with the requirements of qualitative data analysis, and their popularity at the time of the study. Other chatbots listed in Table 2 were not included in the experiments as they did not fully meet the criteria for this study.

Figure 2.

Methodology for user evaluation of Taguette, ChatGPT, and Gemini.

Table 2.

Participants’ Familiarity and Frequency of Use for Various AI Chatbots.

After users had completed the demographic questionnaire, we presented the first task using the Taguette tool. In the first task, they were instructed to perform data annotation on the content.txt file—tagging the survey answers with the core challenges they highlighted. Participants were free to define as many tags as needed. The participants did not receive instructions or restrictions on how to name the tags. In this task, the participants had to identify and prepare a list of the top ten most crucial challenges related to the website’s content based on the qualitative data. When the participants were sure that they had completed the task, they had to submit the result or solution and fill in the questionnaire to assess the implementation of task 1 with the selected tool. In the second task, the participants were asked to categorize the answers in the same dataset based on their sentient as positive or negative. When the participants were sure they had completed the second task, they had to submit their solution via the online system and fill out a questionnaire to evaluate the implementation of task two with the selected tool. After participants completed and submitted both task results and answered the task-related surveys, users were asked to answer the tool survey. With the tool survey, we captured additional quantitative data on user perceptions of usability and UX when using the tool for qualitative data analysis. After completing the survey for evaluating the first tool (Taguette), the process continued with the same tasks and surveys for evaluating two selected AI-based tools. When users evaluated the ChatGPT tool, they conducted the qualitative data on the ux.txt file, and with the Gemini, participants conducted the qualitative data analysis of the data provided with the structure.txt file.

The tasks were designed to reflect key activities in QDA and align with the study objectives of comparing the usability and UX of AI-based and non-AI-based tools. The first task focused on data annotation, a foundational QDA activity (e.g., [2]). Participants categorised and tagged qualitative data based on themes or patterns, simulating realistic coding activities that require interpretation, pattern recognition, and thematic categorization. This task highlighted the tools’ flexibility and ability to support subjective judgment, which is critical in qualitative research. The second task introduced sentiment analysis, requiring participants to categorize data as either positive or negative. This task was chosen to test the tools’ efficiency and usability in guiding users through structured decision-making processes. Sentiment analysis reflects a common extension of QDA, where researchers analyze emotional tones in textual data (e.g., [7,24]). These tasks were intentionally chosen to examine the tools’ ability to handle open-ended and structured qualitative analysis, covering varying levels of cognitive complexity and decision-making processes. To ensure consistency and avoid familiarity bias, the datasets for each tool were specifically assigned: the content.txt file was analyzed using the traditional tool (Taguette; [30]), while the ux.txt and structure.txt files were analyzed using AI-based tools (ChatGPT and Gemini). The task design supports the study’s primary research questions, particularly comparing usability, UX, trust, and mental workload across different tools during realistic QDA scenarios. Relevant usability criteria, including effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction (e.g., [7,13]), informed the task design to ensure alignment with theoretical foundations and prior research.

3.2. Participants

Participants in this research’s experiments have been recruited at the University of Maribor, Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Participants were users who had previously performed UX evaluations at a basic to advanced level. Two groups of Master’s students in the Informatics and Data Technologies study program were included in this research. These individuals were chosen based on their prior experience in UX evaluations, ranging from basic to advanced levels, making them well-suited candidates for this experiment. Additionally, due to their prior academic background, participants possessed the requisite skills to meaningfully engage with the data coding tasks at hand. At the same time, their lack of prior exposure to the datasets used in the study ensured neutrality, reducing any potential bias stemming from familiarity with the data. Altogether, 85 students participated in the research, of whom 63 were male and 22 female. The first group consisted of 54 first-year Master’s students, and the second group of 31 second-year Master’s students.

All participants were familiar with intelligent chatbots based on large language models. The participants’ tool familiarity level was evaluated before the exercises. The results were included in the demographic presentation of the user sample, and user familiarity was checked for ten of the most common AI-based chatbots available on the market, on a five-point Likert scale (1—Not familiar, 5—Very familiar). The results are presented in Table 2. The highest mean familiarity was observed with ChatGPT ( = 4.62, Std = 0.60). All other chatbots reached lower mean familiarity levels, with Gemini ( = 2.65, Std = 1.23) and Bing ( = 2.55, Std = 1.04) reaching the subsequent highest mean familiarity as self-reported by participants.

Additionally, participants were asked to rate the frequency of their intelligent chatbot use on a scale of 1–5 (1—Never, 2—Very rarely, 3—Occasionally, 4—Frequently, 5—Very frequently). The results are presented in Table 2. Participants expressed a frequent use of ChatGPT ( = 4.39, Std = 0.86) rare use of Gemini ( = 1.85, Std = 1.02) and very infrequent use of other tools. Figure 3 visualizes the mean values for the participants’s familiarity level with AI chatbots and frequency of use level for the selected chatbots.

Figure 3.

Familiarity and Frequency of use for AI Chatbots.

3.3. Measures

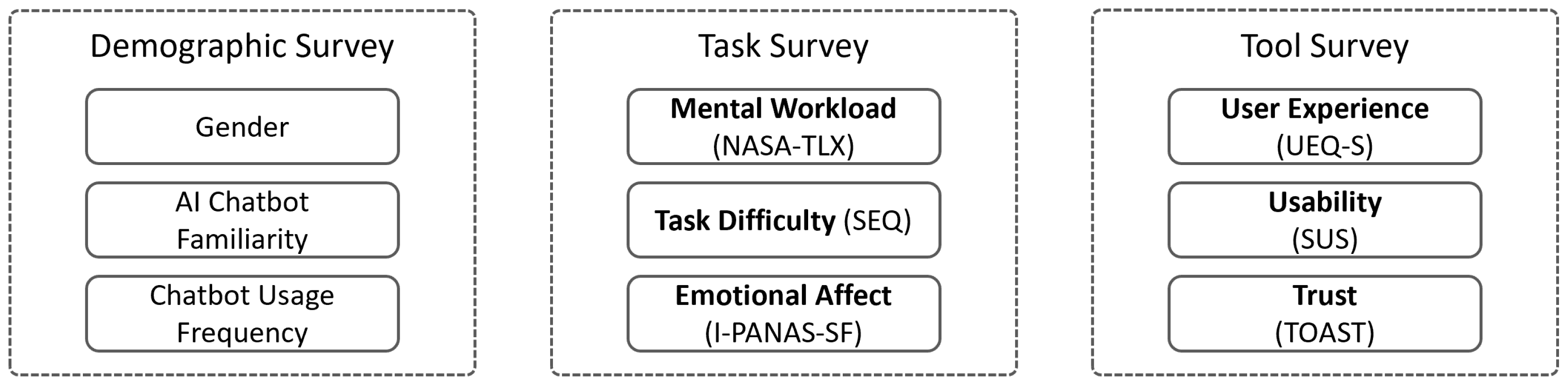

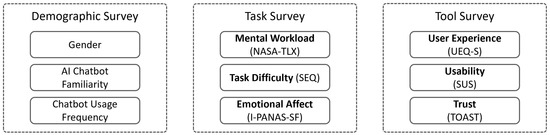

Evaluating the QDA tools involved a comprehensive assessment from two perspectives: the task’s complexity and the user experience (UX) during task completion. Each tool was assessed using standardized surveys designed to evaluate five dimensions: UX, usability, trust, mental workload, and task difficulty. To achieve this, three questionnaires were designed, each tailored to specific stages of the evaluation process. These surveys captured multiple aspects of UX and usability, and Figure 4 provides an overview of the evaluated factors and their corresponding measurement instruments.

Figure 4.

Surveys Used in the Experiment, Including Measured Factors and Corresponding Measurement Instruments.

The evaluations relied on self-reported scales, reflecting participants’ perceptions rather than objective behavior or cognitive process measures. It is important to note that reported trust levels may not directly correspond to trust exhibited in decision-making, and perceptions of workload or difficulty may diverge from actual task performance or cognitive load.

Participants’ general information, including gender, familiarity with chatbots, and the frequency of chatbot use, was collected using a concise Demographic Survey.

Following task completion, a second questionnaire (Task Survey) was administered to gather insights into users’ effort and experience while completing tasks. This survey measured three key factors: mental workload, perceived task difficulty, and emotional affect. The NASA-TLX instrument [75] was used to assess six dimensions of workload: mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration. Each subscale was rated on a 1–20 scale, with an overall score of 0–100 calculated as a simple sum (referred to as Raw TLX or RTLX [76]). Task difficulty was evaluated using the Single Ease Question (SEQ), a validated 7-point Likert scale that performs comparably to other task complexity measures [77]. Additionally, emotional responses were assessed using the I-PANAS-SF, a ten-item scale that measures both positive and negative affect [78].

A third survey (Tool Survey) focused on the usability, UX, and trust associated with each tool. UX was evaluated using the UEQ-S instrument, a shorter version of the User Experience Questionnaire [79]. This tool measures pragmatic and hedonic qualities with 8 items, on a scale ranging from −3 to +3 and allows benchmarking against reference values established from 468 studies [80]. Usability was assessed with the System Usability Scale (SUS), which provides scores ranging from 0 to 100 and allows comparisons with established benchmarks [81,82]. Furthermore, a net promoter score (NPS) was derived from the SUS results as a measure of user loyalty [83]. The final dimension, trust, was evaluated using the TOAST instrument [84], which features two subscales measuring performance trust and understanding trust. This tool uses a seven-point Likert scale. Higher scores on the performance subscale indicate that the user trusts the system to help them perform their tasks, while higher scores on the understanding subscale indicate users’ confidence in the appropriate calibration of their trust. Detailed translations and descriptions of the survey items are provided in the Supplementary Materials to ensure transparency and replicability.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

This study applied different statistical methods to analyze the collected data. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant familiarity and frequency of chatbot use, including means, standard deviations, ranges, and percentages. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for comparative analysis to assess differences between chatbots across factors such as mental workload, trust, and emotional affect. Where significant differences were found, Dunn’s post hoc test was used for pairwise comparisons between tools. Effect sizes were calculated using eta-squared () to measure the magnitude of these differences.

Additionally, reliability analyses were performed using Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement instruments. Correlation analysis, including Kendall’s tau-b and point-biserial correlation, was conducted to explore relationships between variables like task difficulty and mental workload. These statistical techniques provided a robust framework for analyzing the study’s data, enabling in-depth comparisons and validations across different tools and user perceptions.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Data Analysis Results

As presented in Section 3, participants performed QDA with three tools. For each tool, they were presented with a new dataset and two repeating tasks. The first task focused on data annotation and recognizing the repeating challenges. The second task focused on categorizing all instances within the dataset based on their sentient, which was positive or negative.

In the first task, participants recognized more than seventy differently worded categories of challenges. The overlap in recognized categories using synonyms and slightly different wording was significant. The most commonly identified categories were “Too much information”, “Too much irrelevant content”, “Confusing navigation”, “Too much text”, “Lack of content clarity”, “Missing information”, “Missing important information”, “Missing search function", and “No issues/No comments”.

In the second task, participants labeled the answers as positive or negative and submitted the number of recognized positive and negative responses and the ratio between them. Some participants also recognized selected responses as neutral. Not all users submitted valid responses; some only responded with the (private) hyperlink to the chat, which limited the data analysis. For Taguette, 80 valid responses were gathered, for ChatGPT 64 and for Gemini 58. The mean ratio between the positive and negative responses, as recognized by participants from the gathered results, was 36:74 for Taguette (Std = 14.2), 31:69 for ChatGPT (Std = 27.2), and 64:36 for Gemini (Std = 63.2). A larger standard deviation was observed with the use of AI tools. A categorization error was also recognized with this task; some users categorized results multiple times as the sum for their responses was higher than 100 (the sum of all analyzed answers). This error had low representation in the analysis conducted in Taguette (3 responses reported categorization values higher than initial data instances) and Gemini (4 incorrect responses), and higher with ChatGPT, where 16 out of 64 respondents (25% of them) made this error. Participants most likely continued their work in the same chat instance in which they conducted the first task, which led to duplicate counting due to instances in the first task being assigned multiple tags.

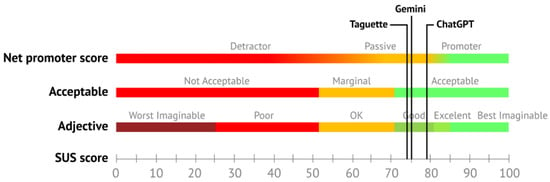

4.2. Usability Evaluation

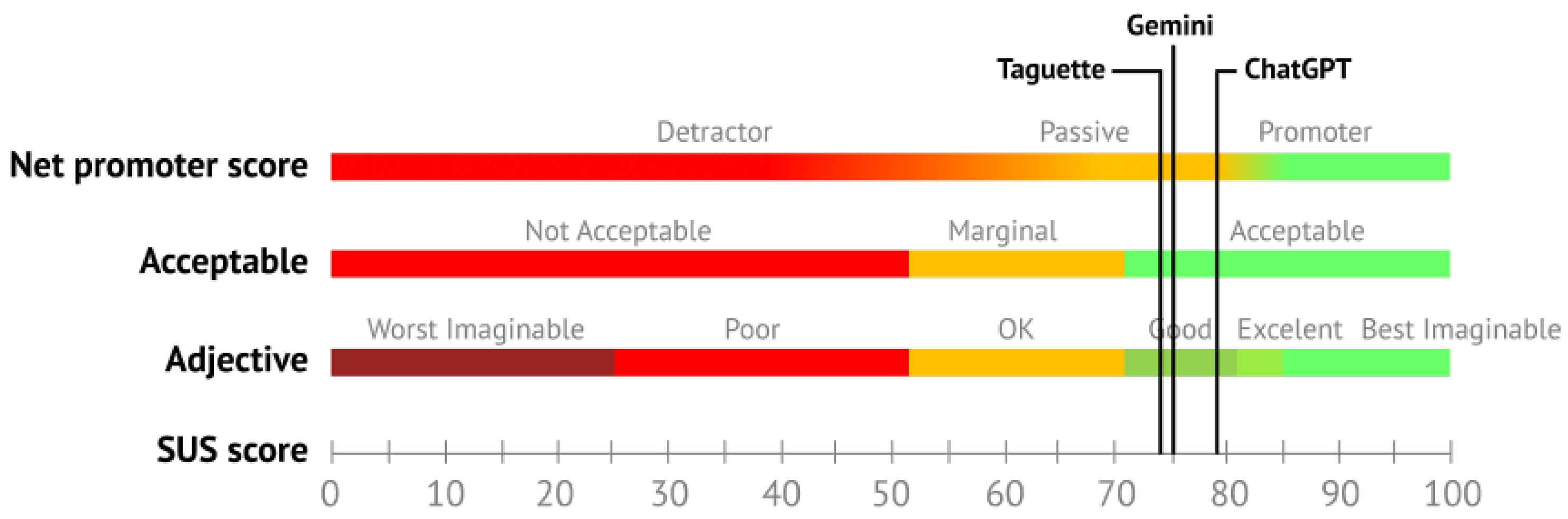

Usability was evaluated using the SUS questionnaire. The results of the SUS score are presented in Table 3. ChatGPT obtained the highest SUS score (SUS = 79.03). Taguette and Gemini achieved similar results with SUS values of 74.95 and 75.08, respectively. Based on the scale’s benchmark, all usability scores are acceptable and can be categorized as good. Based on some interpretations of the lower limits, ChatGPT could also be considered a promotor. Detailed SUS interpretation for all tools is visualized in Figure 5. The reliability of the results obtained with the SUS questionnaire was measured with Cronbach’s alpha and reached = 0.814, indicating very good levels of reliability. Before analysis, all negatively stated items were reversed to avoid negative alpha values. Detailed analysis of reliability for SUS showed very good reliability for ChatGPT and Gemini and an acceptable level of reliability for Taguette. Detailed results are presented in Table 3. Overall, the usability of all three evaluated tools can be considered good, although some positive variance was observed in the ChatGPT score.

Table 3.

Detailed SUS scores of observed tools.

Figure 5.

SUS score interpretation of the tools, interpretation based on [82].

The difference in SUS scores between the tools was tested with the Kruskall–Wallis H Test, which showed no significant difference in the observed tools with , , with a rather small effect size (). An additional pairwise comparison between the SUS scores of the three tools with the Dunn’s Test showed a significant difference between the SUS scores of Taguette and ChatGPT (). No other differences were statistically significant. Results are presented in Table 4. This further indicates that there was no statistical difference between the usability of the AI tools used for the observed two UX evaluation tasks.

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of SUS scores for tools with Dunn’s Test procedure.

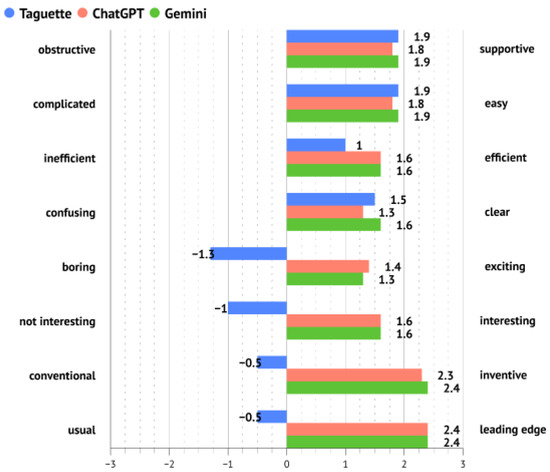

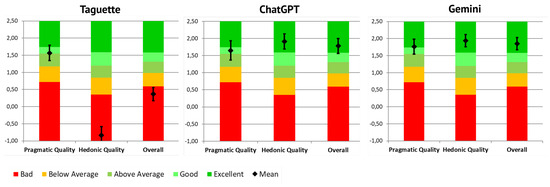

4.3. User Experience Evaluation

As presented in Section 3, UX was evaluated with the UEQ-S tool. Initially, 82 responses were received for Taguette, 83 for ChatGPT, and 84 for Gemini. The results of the pragmatic and hedonic scales and the overall results are presented in Table 5. They indicate an overall positive evaluation, except for Taguette, which was negatively evaluated in hedonic quality (slightly suppressing the benchmark of <0.8). Taguette tool was evaluated as neutral overall, while ChatGPT and Gemini achieved a positive overall evaluation.

Table 5.

Results of UEQ Scales for observed tools.

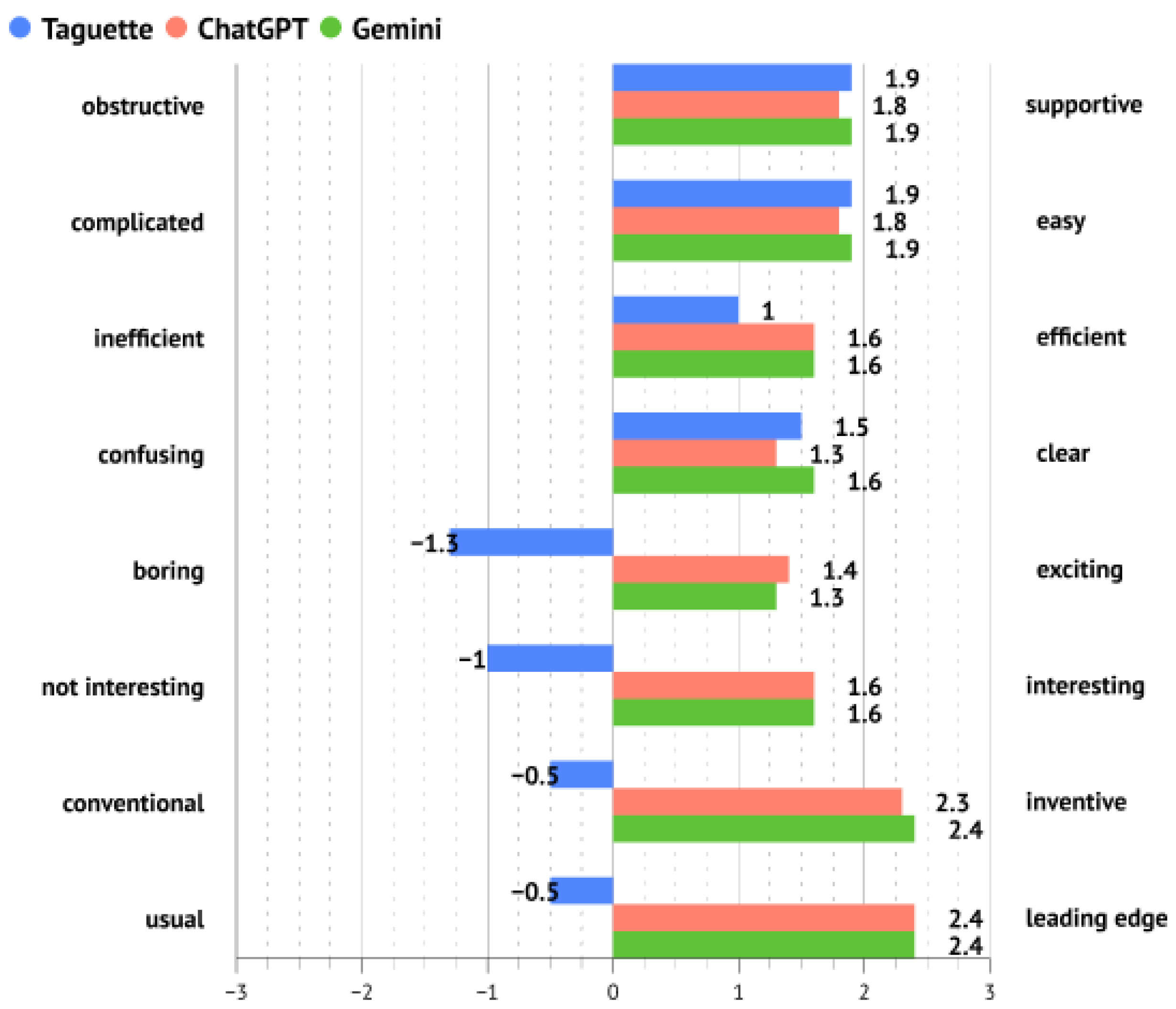

Mean values per UEQ-S item are presented in Figure 6. They show very similar results for ChatGPT and Gemini and some disparities for Taguette. Taguette tool was perceived as similarly supportive, easy, and clear as other tools, but less efficient than them. The previously mentioned, the difference in hedonic quality items is visible; users evaluated Taguette as more boring, not interesting, more conventional and usual compared to the other two tools. Cronbach’s Alpha values were analyzed separately for pragmatic and hedonic scales. They reached = 0.814 and = 0.803 in the whole sample. In the Taguette sample, they reached = 0.70 and = 0.80, in the ChatGPT sample they reached = 0.90 and = 0.82, and on the Gemini sample they reached = 0.82 and = 0.80. All values indicate good to very good consistency.

Figure 6.

Mean values of UEQ-S items per observed tool.

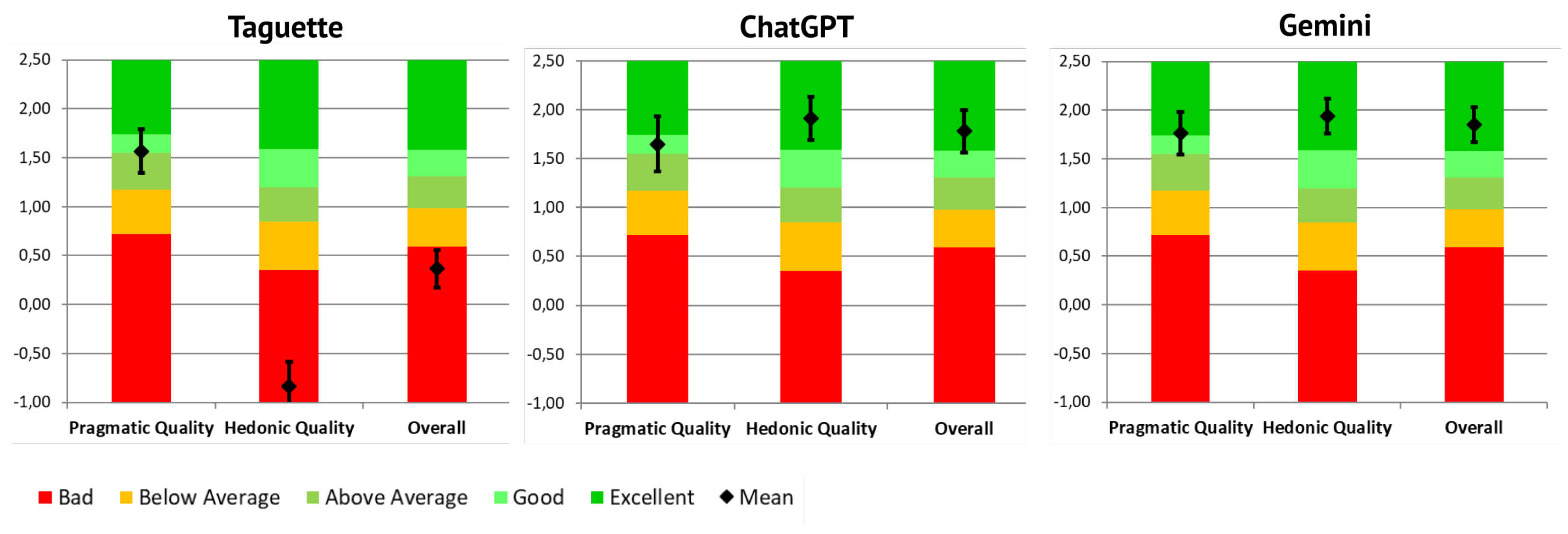

The results of all three observed tools compared to the benchmark values are presented in Figure 7. The pragmatic quality of the Taguette and ChatGPT tool is considered ’Good’, while Gemini reached the threshold for ’Excellent’ quality. The hedonic quality of the Taguette tool was evaluated as ’bad’, which is placed in the range of the 25% worst results. On the contrary, ChatGPT and Gemini were positioned as ’Excellent’, i.e., in the range of the 10% best results. The difference in the hedonic value for the Taguette tool is also reflected in its positioning of the overall scale.

Figure 7.

Benchmarked values of UEQ-S scales per tool.

The difference in the UEQ Scale scores between tools was analyzed with a Kruskall–Wallis H test. The results showed a significant difference in overall UEQ score, , with a very large effect size (). Taguette reached the lowest mean rang with 58.43, followed by ChatGPT with 149.09 and Gemini with 160.48. An additional pairwise comparison conducted with the Dunn’s Test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in overall UEQ score between Taguette and ChatGPT () and between Taguette and Gemini (). There was no statistically significant difference between the observed AI tools. The results of the Dunn’s Test are presented in Table 6. They confirm the previously indicated difference in UX of the AI and non-AI tools in this context.

Table 6.

Pairwise comparison of UEQ-S scores for tools with Dunn’s Test procedure.

4.4. Cognitive Load and Emotion Correlation

We further explored the relationship between cognitive load and emotional response to understand how workload influenced users’ emotions. No meaningful correlation between positive emotion and NASA-TLX scores (workload, frustration, and others) was identified (). Correlation estimates for individual tools also showed no significant correlation between the workload and positive emotions for Taguette (, ), ChatGPT (), and Gemini (). However, a statistically significant moderate to strong positive correlation existed between negative emotion and NASA-TLX (). This result suggests that higher cognitive demands, effort, and frustration are associated with increased negative emotions. QDA tools that lead to higher cognitive demands and effort tend to evoke more negative emotions in users.

There were significant correlations between NASA-RTLX scores and negative emotions such as nervousness (), upset (), hostility (, ), and guilt (). These correlations suggest that as users’ workload and effort increase, they tend to report higher negative emotional states, such as feeling more nervous, upset, or hostile. There were weak and primarily negative correlations between positive emotions, such as determination () and inspiration (). These results indicate that a higher workload is associated with lower positive emotions like determination and inspiration, although the correlations are weaker than those with negative emotions. The analysis reveals a clear emotional response associated with perceived workload, particularly for negative emotions like nervousness, frustration, hostility, and guilt, which increase with higher workload scores. On the other hand, emotions like determination and inspiration decrease with increased workload, showing that cognitive and emotional load affect the user’s emotional experience. While some emotions, like alertness and attention, are less affected, the overall trend suggests that workload negatively impacts users’ emotional state.

4.5. Trust Evaluation

As presented in the methodology Section 3, trust was evaluated with the TOAST questionnaire. Altogether, 249 valid responses were obtained (three participants did not finish the trust survey—two responses were missing for Taguette evaluation and one for ChatGPT). Results were analyzed according to the two recognized subscales; performance and understanding. The reliability of the obtained results was measured with Cronbach’s alpha and reached = 0.779 for items in the understanding subscale (items one, three, four, and eight of the questionnaire) and = 0.805 for items in the performance subscale (items two, five, six, seven, and nine of the questionnaire). Reliability remained high after observing the results per tools—for performance subscale = 0.805, = 0.853, = 0.805, and understanding subscale = 0.735, = 0.826, = 0.813. All the observed reliability values range from good to acceptable.

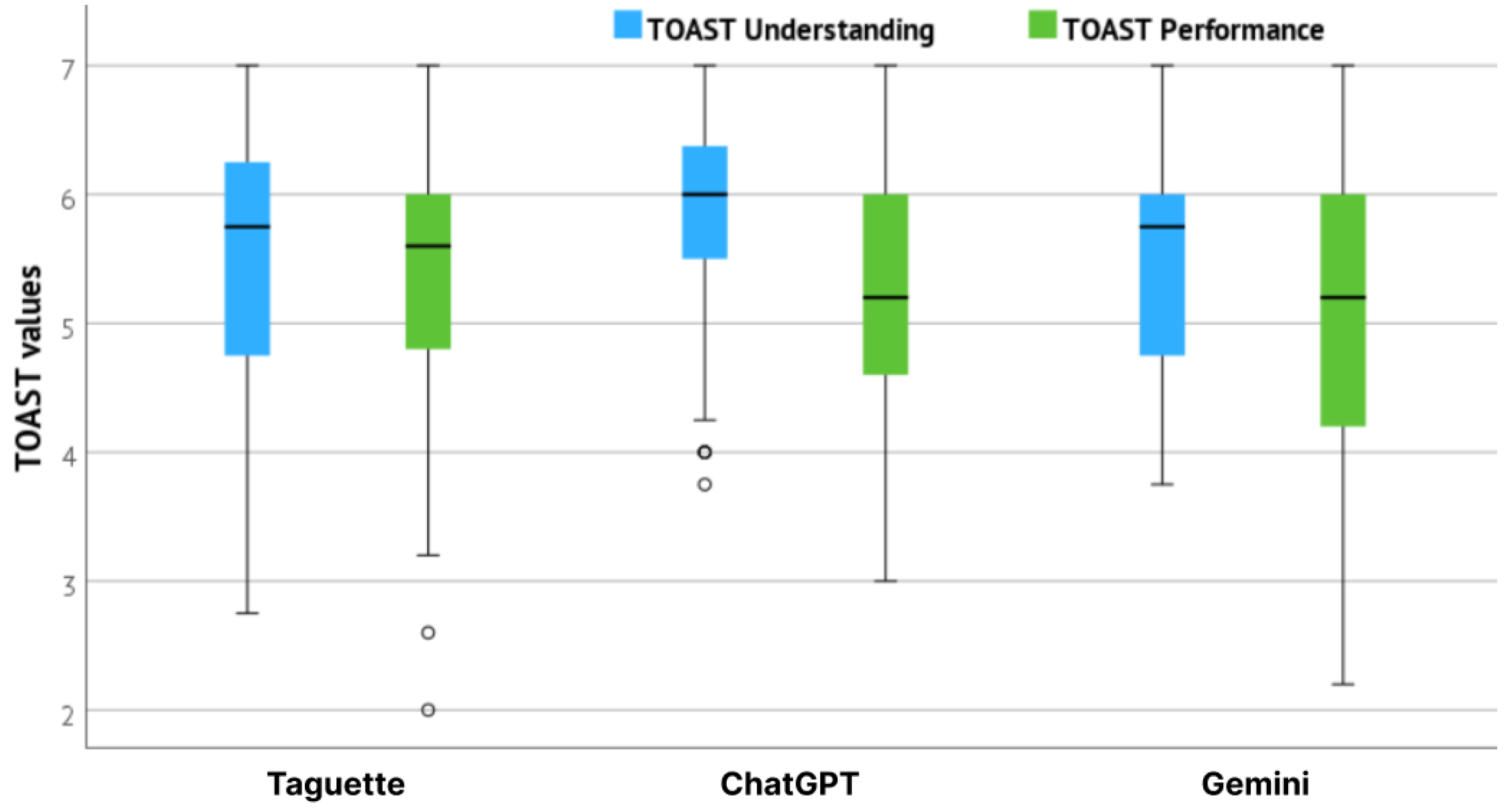

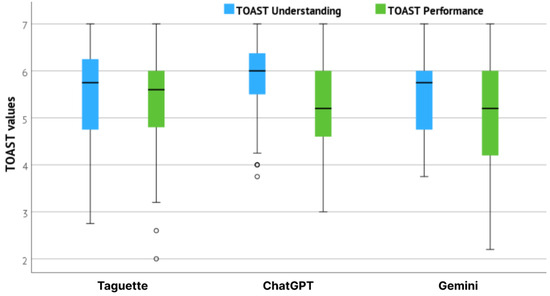

The results of TOAST understanding and performance subscales per tools are presented in Figure 8. Observing the performance subscale, which indicates users’ trust that the system will help them perform their task; Taguette reached the highest mean value with 5.38 (Std = 1.00), followed by ChatGPT with 5.17 (Std = 0.96), and Gemini with 5.10 (Std = 1.05). Therefore, users trusted Taguette the most to help them perform their UX evaluation tasks. Observing the understanding subscale, which indicates users’ confidence about the calibration of their trust, ChatGPT reached the highest mean value with 5.88 (Std = 0.80), followed by Gemini with 5.53 (Std = 0.89), and Taguette with 5.47 (Std = 1.03). The results of understanding subscale are correlated with the participants’ familiarity and frequency of use for AI tools, which was highest for ChatGPT and followed by Gemini in both cases (data previously presented in Table 2). The users had previous experience with these two tools, which allowed them to calibrate their trust.

Figure 8.

TOAST values for Taguette, ChatGPT and Gemini.

The difference in both trust subscales between the tools was tested with a Kruskall–Wallis H test, which showed that there was a statistically significant difference in understanding subscale scores between the observed tool, , , with a mean rank 143.58 for ChatGPT, 116.60 for Taguette, and 114.85 for Gemini. Additionally, Dunn’s Test for pairwise comparison was performed, results of which are presented in Table 7 and showed a statistically significant difference in understanding subscale between the ChatGPT and Gemini () and Taguette and ChatGPT (), meaning users were more sure in the calibration of their trust when using ChatGPT compared to Gemini and to Taguette, separately. No significant difference was observed between Taguette and Gemini. Kruskall–Wallis H test additionally showed a statistically significant difference on the performance subscale with , and mean rank 138.48 for Taguette, 120.95 for ChatGPT, and 115.85 for Gemini. Dunn’s Test showed a statistically significant difference on a performance subscale between Gemini and Taguette (), meaning users trusted Taguette more to help perform their tasks, compared to Gemini. The effect size of both Kruskall–Wallis tests was quite small with and .

Table 7.

Pairwise comparison of TOAST scores for tools with Dunn’s Test.

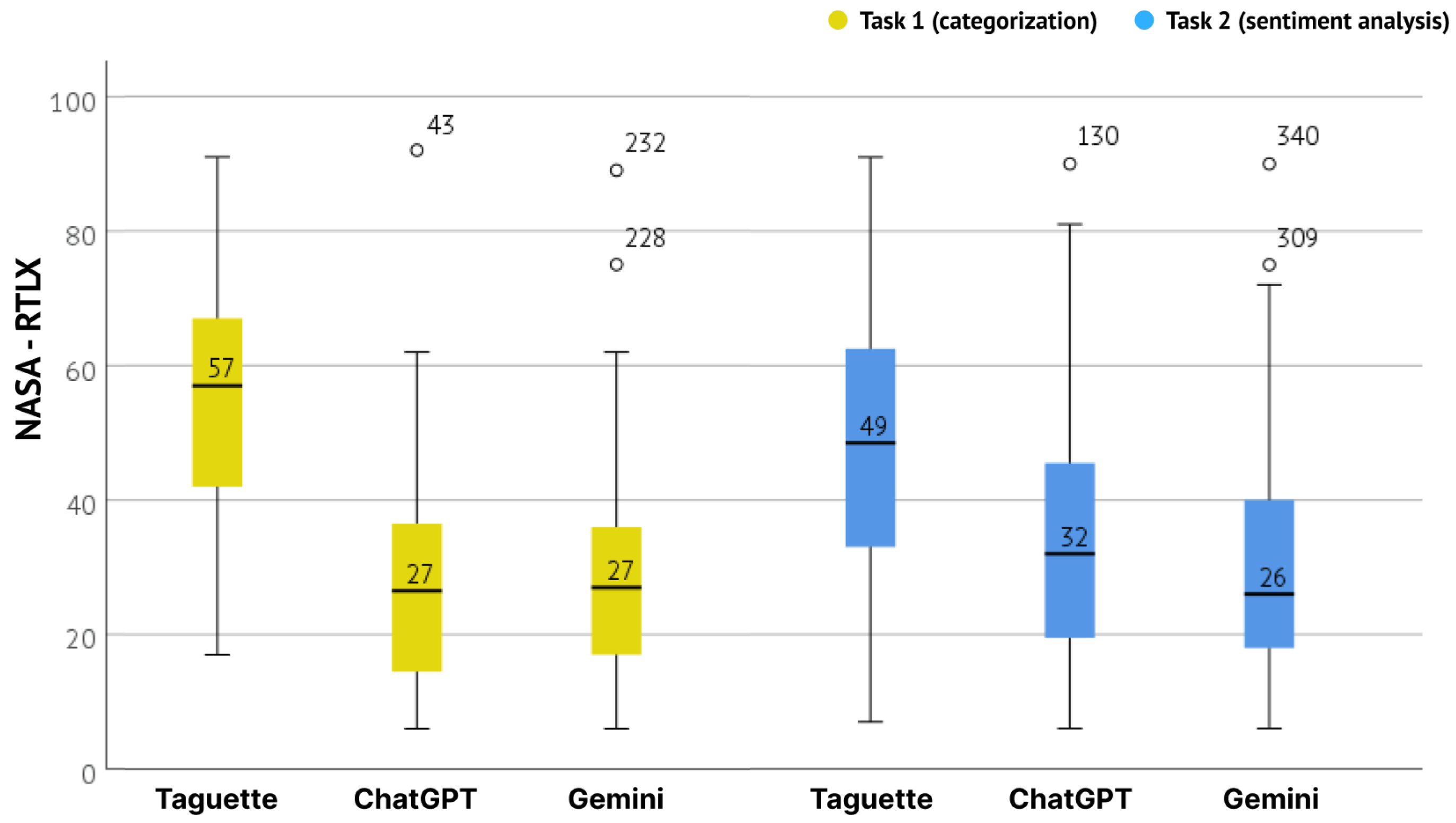

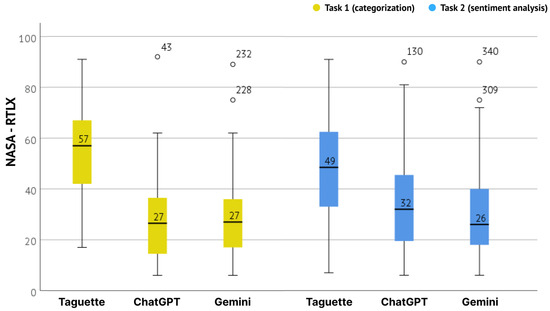

4.6. Mental Workload Evaluation

Mental models were evaluated separately for both tasks (categorization and sentiment analysis) using the NASA-RTLX. An overview of the resulting values (sum values of six subscales) by tools and tasks is presented in Figure 9. It is visible that users reported a higher mental workload when using the Taguette tool in both tasks. The mean NASA-RTLX value for Taguette was 57 () for the first task and 49 () for the second. Meanwhile, the mean value for other tools was between 26 and 32 for both tasks (). The mean values for the tools remained quite consistent between the first and second tasks. The difference between them for observed tools was further confirmed with a Kruskall–Wallis H test. It showed a statistically significant difference in the NASA-RTLX score between the different tools used for the UX evaluation on both tasks.

Figure 9.

NASA-RTLX values for Taguette, ChatGPT, and Gemini, per tasks.

For the first task, this was confirmed with (2) = 36.607, , with a mean NASA-RTLX score of 69.99 for ChatGPT, 103.20 for Gemini and 189.16 for Taguette. The effect size, calculated using eta-squared was 0.136, indicating a small effect. And for the second with , with a mean NASA-RTLX score of 114.18 for ChatGPT, 99.90 for Gemini, and 164.90 for Taguette. The effect size for the second task was very large (), indicating a substantial difference in perceived workload across the three systems. Additional pairwise comparison, conducted with Dunn’s Test indicated a clear difference between the AI and non-AI tools. For both tasks, the difference was statistically significant in comparison of ChatGPT and Taguette (, ) and in comparison of Gemini and Taguette (, ). The results of Dunn’s Test are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Pairwise comparison of NASA-RTLX scores for tools with Dunn’s Test procedure.

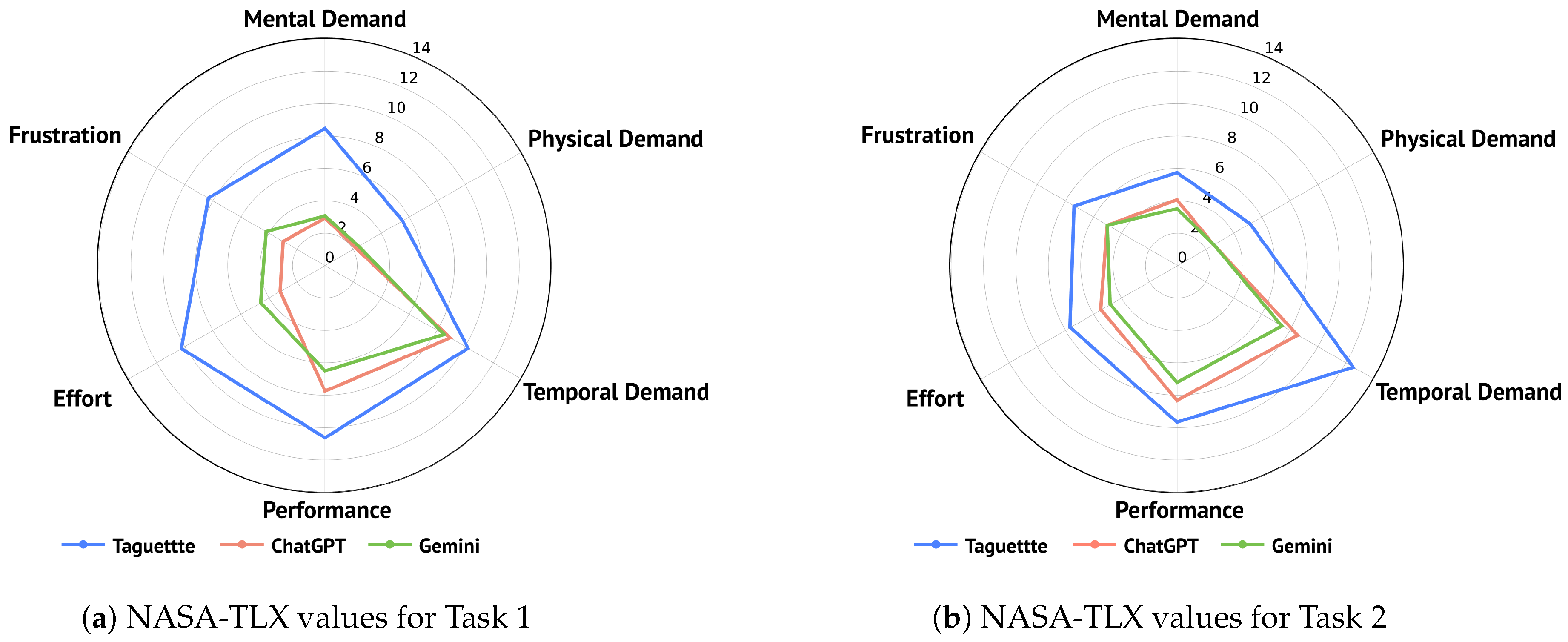

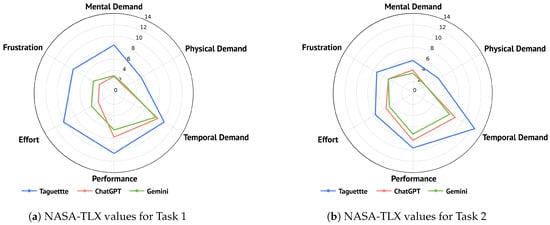

The detailed overview of the subscale values is presented in Table 9. Taguette consistently shows higher mental demand compared to the AI tools, especially in the first task (). Both ChatGPT and Gemini present significantly lower mental demands, with ChatGPT reaching the lowest mean value for the first and Gemini for the second task (). With the use of Taguette users experienced higher temporal demands, particularly in the second task, suggesting that AI tools helped them in managing perceived time pressure better (the experiment had no time restraints for tasks). The subscale performance revealed that users were more satisfied with their performance when using Taguette in the first task, though this satisfaction slightly decreased in the second task, while the satisfaction with their performance when using AI tools improved. However, Taguette reached the highest mean values for perceived performance in both tasks (). The effort required to complete the task was quite higher for Taguette tool, especially in the first task (), compared to the use AI tools (). This could indicate that the use of AI tools could aid efficiency. Observing the frustration subscale, Taguette, users experience higher frustration levels across both tasks. With the use of AI tools for the tasks, particularly ChatGPT, users showed much lower frustration levels (e.g., for the first task ). Mean NASA-TLX values for each tool are visualized in Figure 10, with Figure 10a representing the results for Task 1 and Figure 10b representing the results for Task 2.

Table 9.

NASA-TLX values Taguette, ChatGPT, and Gemini, per tasks.

Figure 10.

NASA-TLX values for Taguette, ChatGPT, and Gemini, per dimension, for Task 1 (a) and Task 2 (b).

Kruskall–Wallis H tests were used to analyze the difference between the tools for each subscale and task. The results are also reported in Table 9. The test indicated a significant difference between tools in all six subscales. Observing the first task, for mental demand, , Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 186.43, followed by Gemini with 104.26 and ChatGPT with 98.64. For physical demand, , , Taguette also reached the highest mean rank with 167.84, followed by Gemini with 113.92 and ChatGPT with 107.21. For temporal demand, , Taguette also reached the highest mean rank with 146.62, followed by ChatGPT with 121.36 and Gemini with 120.83. The results were similar for the performance subscale, , where Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 161.35, followed by ChatGPT with 119.63 and Gemini with 108.40. A significant difference was also observed for effort, , as Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 190.41, followed by Gemini with 110.93 and ChatGPT with 87.54. Lastly, for frustration, , Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 173.35, followed by Gemini with 118.93 and ChatGPT with 96.35. Similar results were observed for the second task, with slight changes in mean rank order for ChatGPT and Gemini. For mental demand, , Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 152.32, followed by ChatGPT with 118.98 and Gemini with 107.80. For physical demand, , Taguette also reached the highest mean rank with 155.31, followed by ChatGPT with 114.90 and Gemini with 109.09. The results were similar for temporal demand, , as Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 159.75, followed by ChatGPT with 116.36 and Gemini with 102.91. For performance in the second task, , Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 141.17, followed by ChatGPT with 125.01 and Gemini with 112.89. For effort, , Taguette again reached the highest mean rank with 155.00, followed by ChatGPT with 119.44 and Gemini with 104.53. Lastly, for frustration, , Taguette reached the highest mean rank with 149.20, while ChatGPT and Gemini reached similar values with 115.29 and 115.01, respectively. The effect sizes observed in the first task indicate large effect sizes for most of the observed subscales (). A small effect size was observed only on the subscale for temporal demand (), while a medium effect size was observed on the performance subscale (). For the second task, most subscales indicated a medium effect size (). A small effect size was observed for performance () and frustration subscales ().

As both NASA-RTLX and SEQ measure the required effort to complete the task (at least in some form), the correlation between these tools was further analyzed. A Kendall’s tau-b correlation was run to determine their relationship on the entire sample of answers (all tasks, with all tools). There was a strong, positive correlation between SEQ and NASA-RTLX, used for measuring the perceived workload, which was statistically significant (). Additionally, Point-Biserial Correlation was used to analyze the errors recognized in the second task with NASA-RTLX responses, which proved insignificant (r). Correlation between the error rates in the second task and SEQ was analyzed with Pearson Chi-Square, though again, no statistically significant association between them was observed ).

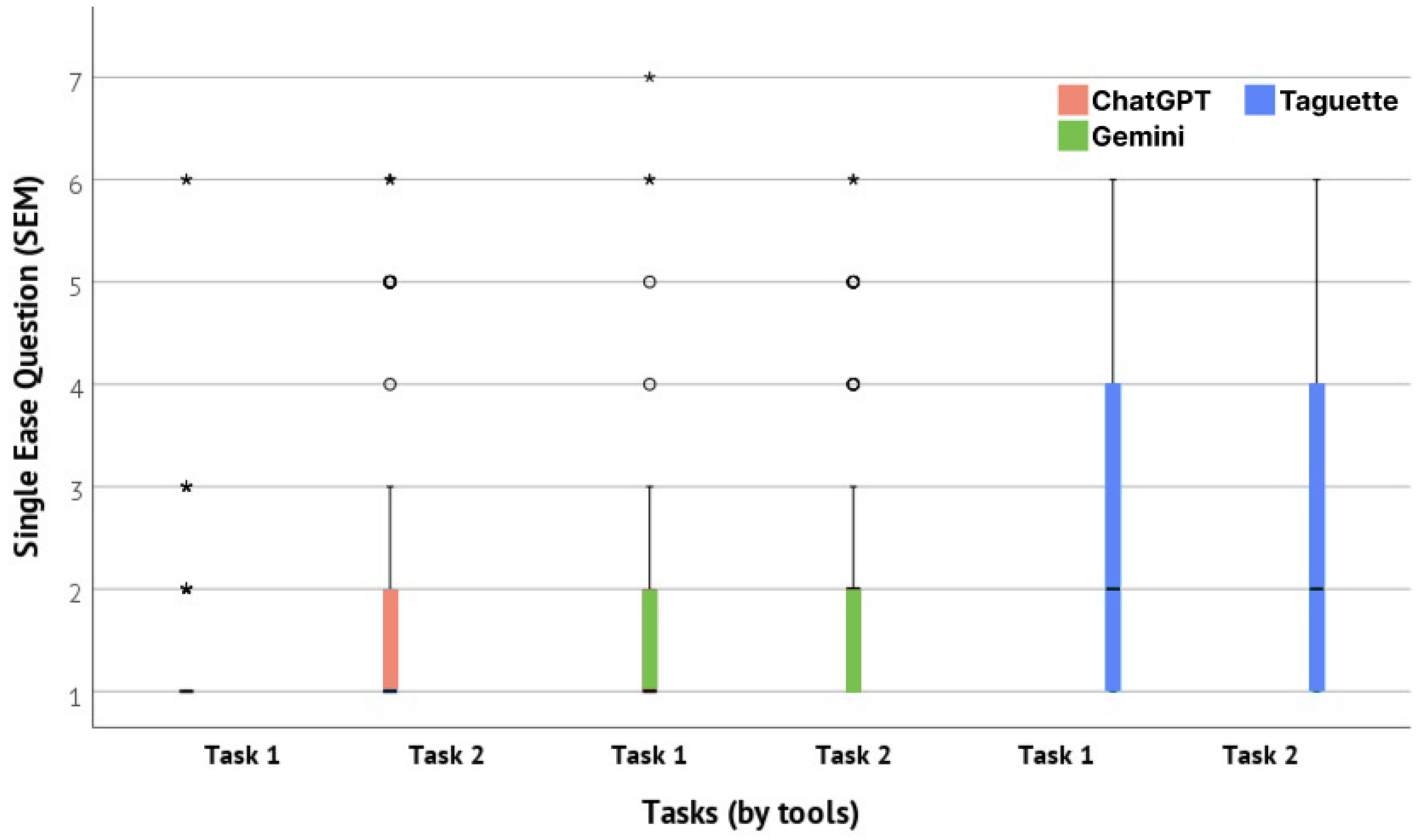

4.7. Task Dificulty

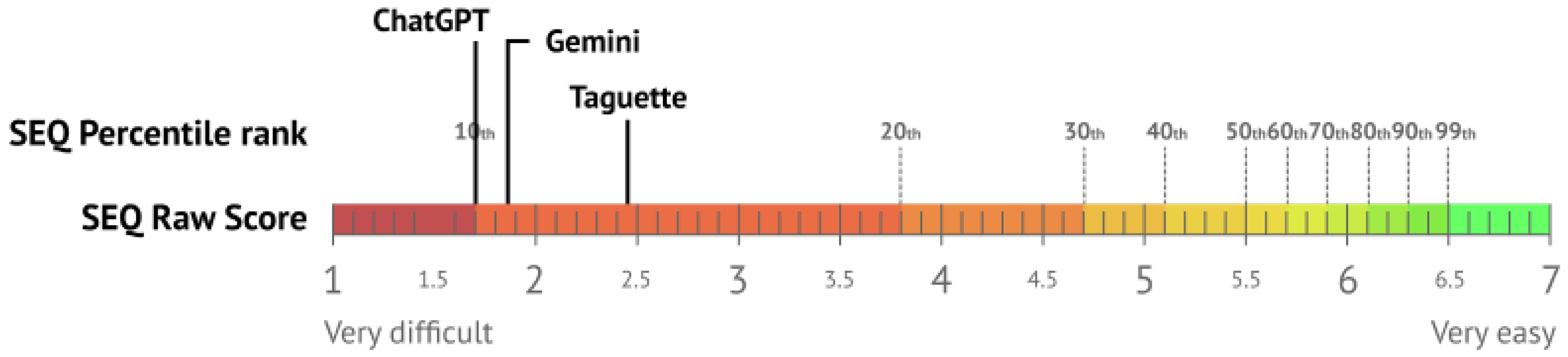

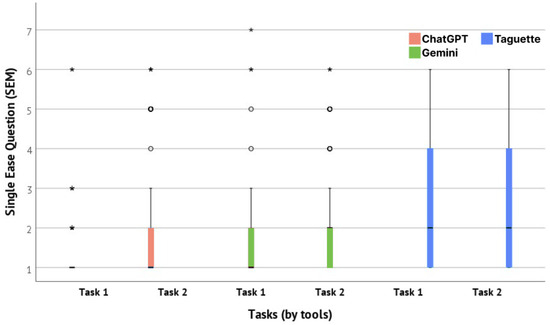

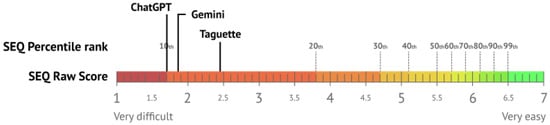

Task difficulty was determined with The Single Ease Question (SEQ), a seven-point rating scale (1—Very Difficult, 7—Very Easy) used to assess how difficult users found the task. SEQ was administered after each task. For Task 1, Taguette scored a mean SEQ of 2.66 (Std = 1.48), ChatGPT had a mean of 1.38 (Std = 0.92), and Gemini had a mean of 1.71 (Std = 1.22). In Task 2, Taguette again reached the highest mean of 2.26 (Std = 1.51), ChatGPT had a mean of 2.05 (Std = 1.51), and Gemini scored a mean of 2.02 (Std = 1.37). Mean values and data distribution are presented in Figure 11. The visualization indicates that Taguette consistently showed higher mean SEQ scores across both tasks, suggesting it was perceived as more challenging to use. These results highlight that the use of ChatGPT generally eased the complexity of the tasks conducted in this study. The overall mean SEQ scores for all three observed tools based on the reference values presented by [85] are visualized in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Distribution of the SEQ values, per task per tool.

Figure 12.

Interpretation of mean SEQ values per tool, based on [85].

The difference between the SEQ results for observed tools was further confirmed with a Kruskall–Wallis H test. It showed a statistically significant difference in the SEQ score between the different tools used for the evaluation of the first task with , with a mean rank SEQ score of 98.05 for ChatGPT, 119.37 for Gemini, and 171.19 for Taguette. Effect size, measured with indicated a large effect size with the value of 0.1972. No statistical difference was observed in the SEQ values between the tools for the second task, with the Kruskall–Wallis H test (). Additionally, a negligible effect size was observed with this test (). Further pairwise comparison, conducted with Dunn’s Test indicated a clear difference between the tools for the first task. The difference was statistically significant in comparison of ChatGPT and Taguette (), in comparison of Gemini and Taguette (), as well as in comparison of ChatGPT and Gemini (). The results of Dunn’s Test are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Pairwise comparison of SEQ scores for tools (Task 1) with Dunn’s Test.

4.8. Emotional Affect Evaluation

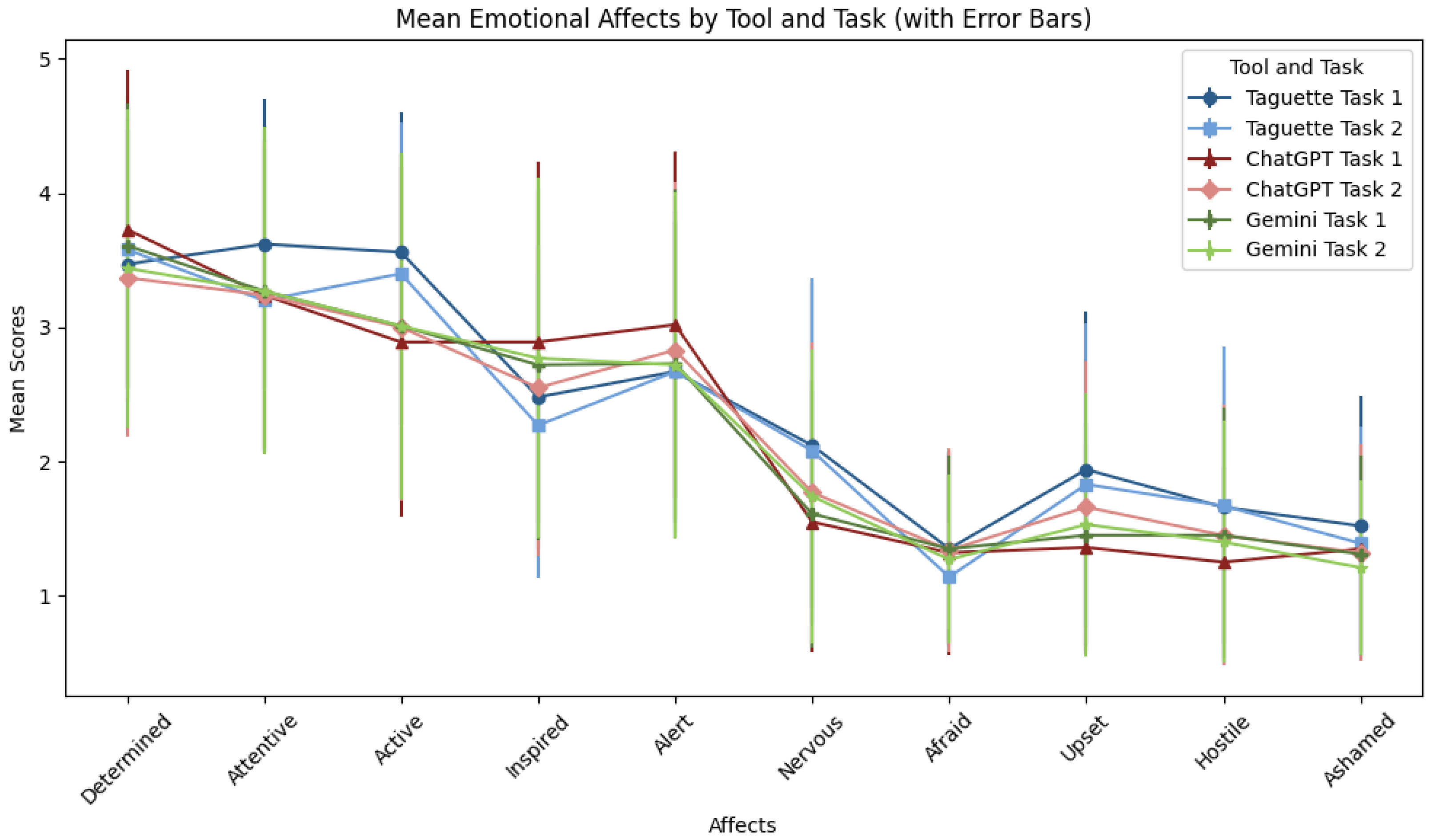

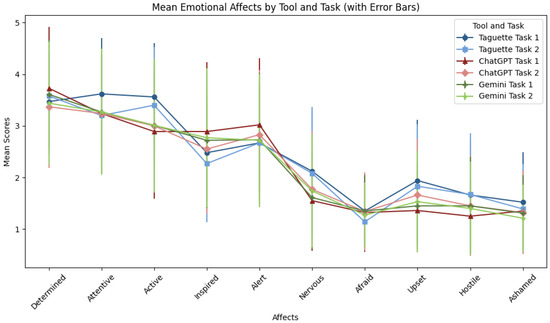

Table 11 shows the descriptive statistics of the I-PANAS-SF items for both tasks and all three tools (Figure 13). Regarding the determination, the average scores varied from 3.37 to 3.73 for each tool and task. Task 1’s ChatGPT tool had the highest average score, suggesting that users felt more determined when using this tool for their job. The Taguette had the highest mean value (3.62) for Task 1, indicating more attentiveness to this tool and task. The scores for attentiveness varied slightly. Using ChatGPT to solve Task 1 resulted in users being less active than Taguette, with a mean value of 3.56. The ChatGPT tool inspired users the most when they completed Task 1 (score of 2.89). With ratings ranging from 2.67 to 3.02, all three tools demonstrated a moderate level of awareness for each of the three tasks and tools.

Table 11.

Descriptives for I-PANAS-SF for all tools and tasks.

Figure 13.

Mean Emotional Affects By Tool And Task.

Users were the least nervous while completing Task 1 using the ChatGPT (1.55) and the most nervous when they had to complete Task 1 using the Taguette tool (2.12). The mean scores for all tools and tasks were quite low, indicating that users rarely felt afraid. Task 1 with the Taguette tool received the highest score for upset emotions (1.94), whereas in the case of other tools and tasks, the upset scores were lower. Hostility scores were modest, with slight variations among tasks and tools and the lowest score for ChatGPT in the case of solving Task 1 (1.25). Overall, feelings of humiliation were slight across all tools and tasks, with Gemini scoring the lowest (1.21) in the case of Task 2.

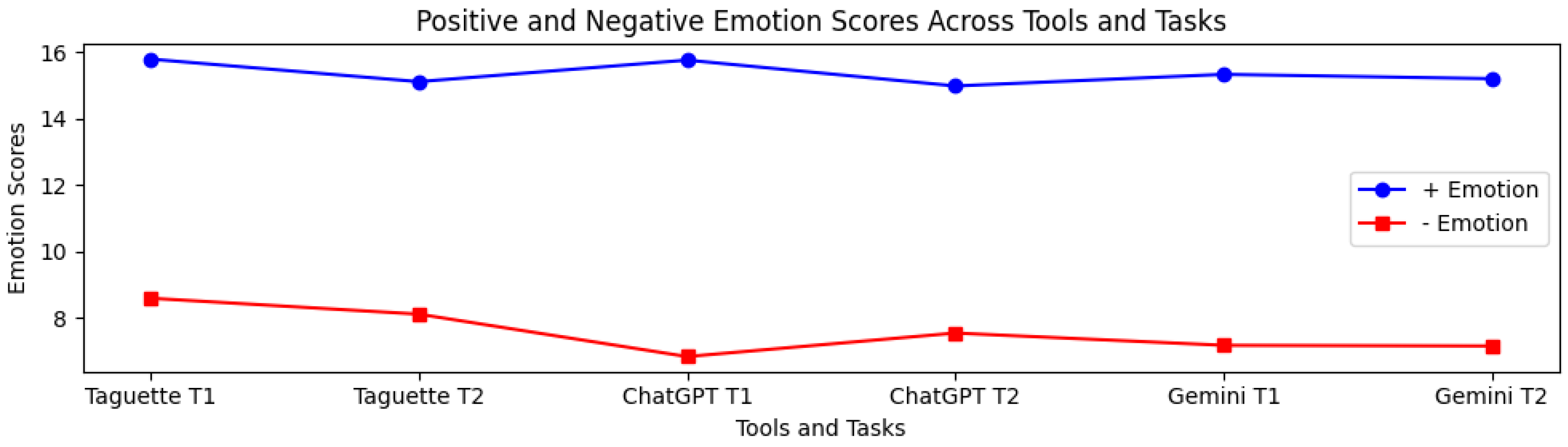

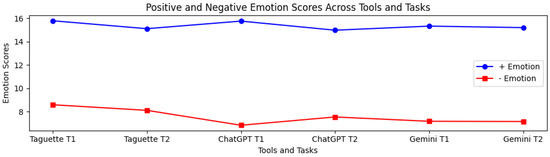

Positive emotion scores were relatively high across all tools and tasks, where the highest positive emotional response (15.77) was in the case of ChatGPT and Task 1, and the lowest score (14.99) was in the case of ChatGPT and Task 2 (see Table 12 and Figure 14). In the case of negative emotions, the instrument provided the highest negative emotions (8.59) for the Taguette tool and solving Task 1. At the same time, ChatGPT Task 1 produced the lowest negative emotional response (6.83), indicating that ChatGPT generally leads to lower negative emotional experiences.

Table 12.

Comparisson of emotional affects between tasks and QDA tools.

Figure 14.

Positive and Negative Emotion Scores per Tool And Task.

In the case of the Taguette tool, the positive emotion scores are relatively consistent, with Task 1 slightly higher than Task 2. Positive emotion estimates were relatively higher compared to other tools. In the case of ChatGPT, we noticed a slight drop in positive emotion from Task 1 to Task 2. However, the positive emotion scores for ChatGPT remained high overall, indicating that completing the tasks with ChatGPT performed consistently well. For Gemini, the positive emotion scores were also similar for both tasks, where Task 1 slightly outperformed Task 2. The emotions were moderately high but consistent between both tasks for the Taguette tool. In the case of the ChatGPT, the participants had the lowest negative emotion scores across both tasks. And in the case of Gemini, the scores for the emotions were slightly higher when compared to ChatGPT, but similar to Taguette.

Comparing emotional effects between tasks and tools (see Table 13) showed that while positive emotional experiences were comparable across tasks and tools, negative emotions varied more significantly, particularly between Taguette and the AI-based tools (ChatGPT and Gemini). For positive emotions, the statistical tests showed no significant differences in positive emotions between tasks or tools, meaning all tools and tasks generated similar levels of positive emotions. The Mann–Whitney U test estimates were small (e.g., −1.17, −0.33), and the p-values were higher than 0.05, indicating no significant differences between the compared groups. Positive emotion scores were also compared between all three tools with the Kruskal–Wallis H test, which resulted in nonsignificant values (), indicating no statistically significant difference between the three tools.

Table 13.

Comparisson of positive and negative effects between tasks and tools.

When we compared negative emotion scores between all three tools, significant differences were found in negative emotions between the tools. The Kruskal–Wallis H test yielded a more significant statistic (27.06) with a p-value , indicating significant differences in the negative emotion scores across all three tools. Comparison of negative scores between the two different tools provided results with higher values (e.g., −4.36, −4.51) and p-values , indicating significant differences between tools. The Mann–Whitney U test revealed significant differences between Taguette vs ChatGPT and Taguette vs Gemini () but no significant difference between ChatGPT vs Gemini.

To summarize, the ChatGPT tool generated higher positive and lower negative emotions, especially in the case of Task 1. Compared to ChatGPT, Taguette demonstrated good positive emotion scores, but, the tool triggered slightly stronger negative feelings, particularly in the case of Task 1, in which users felt more scared, agitated, and hostile. Though it produced more adverse emotions than ChatGPT, Gemini had comparatively balanced emotion scores for both tasks. According to the estimated scores, ChatGPT seems to be the tool of choice.

5. Discussion

This study examined significant differences in usability, UX, trust, task difficulty, emotional affect, and mental workload between chatbots and non-AI tools in qualitative data analysis, revealing key insights into how these tools impact user perception.