Vision-Based Damage Detection Method Using Multi-Scale Local Information Entropy and Data Fusion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

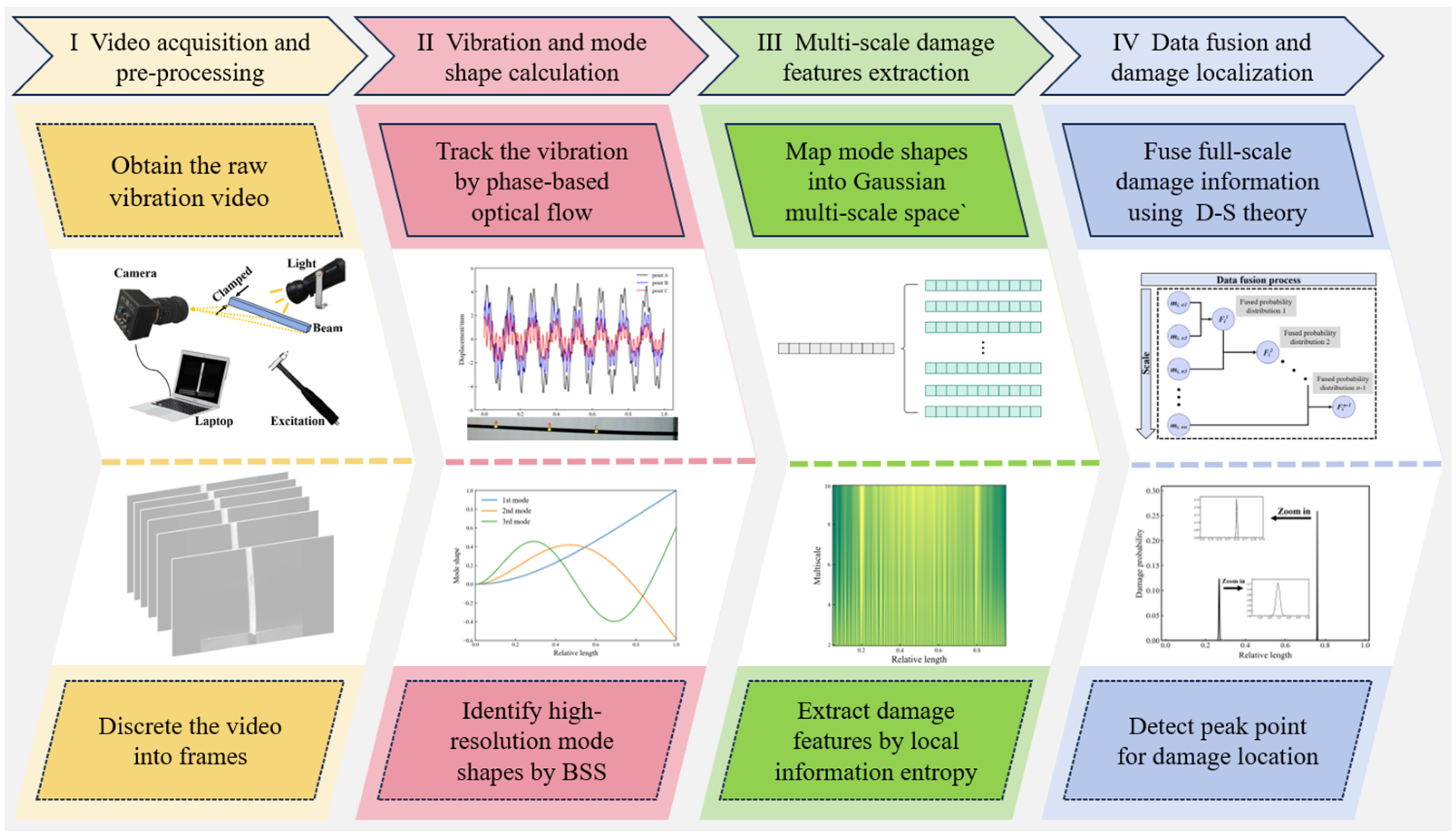

2. Methodology

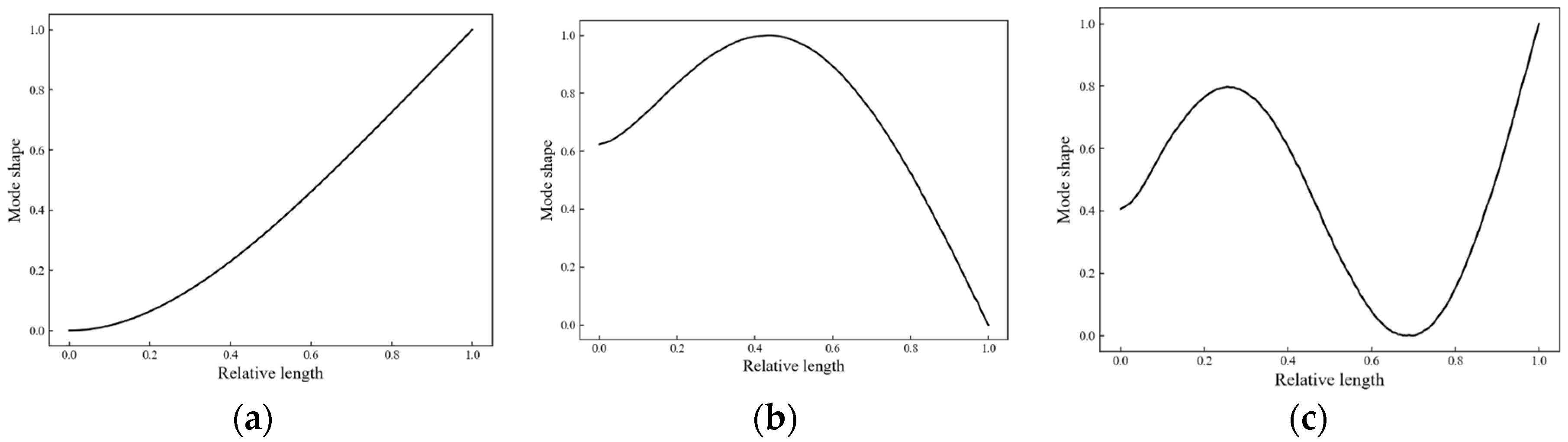

2.1. High-Spatial-Resolution Mode Shapes via Phase-Based Optical Flow Estimation

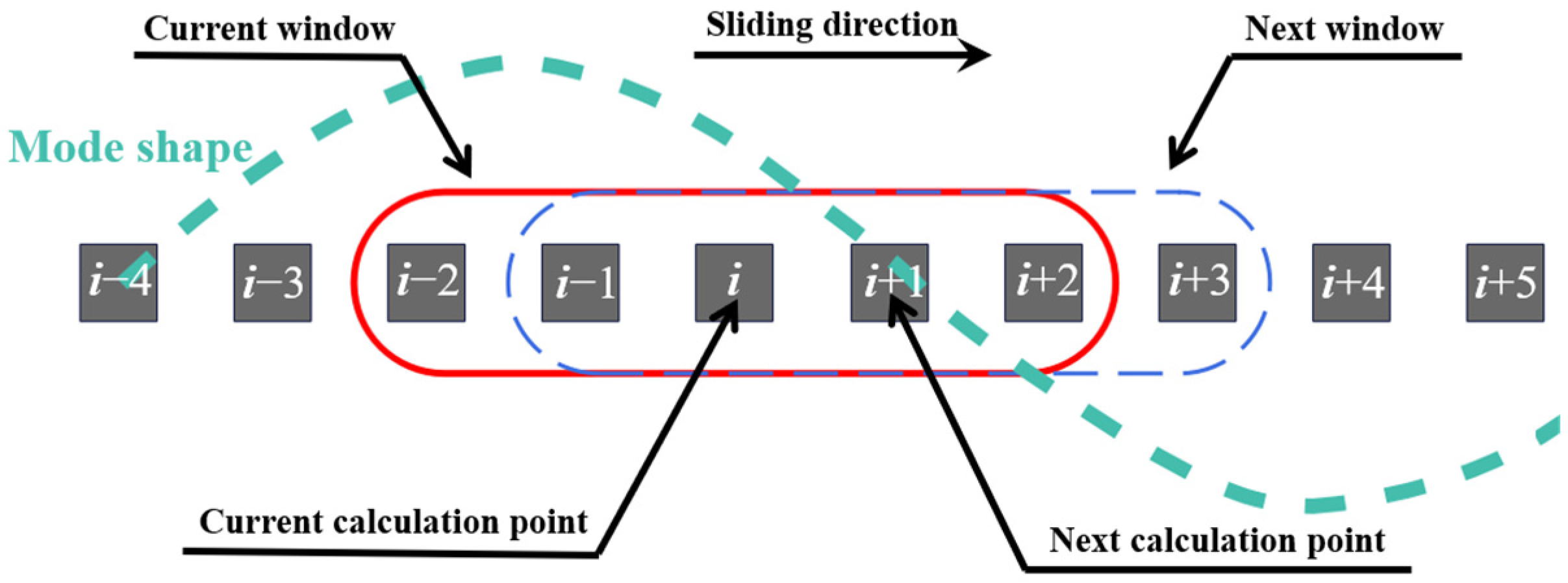

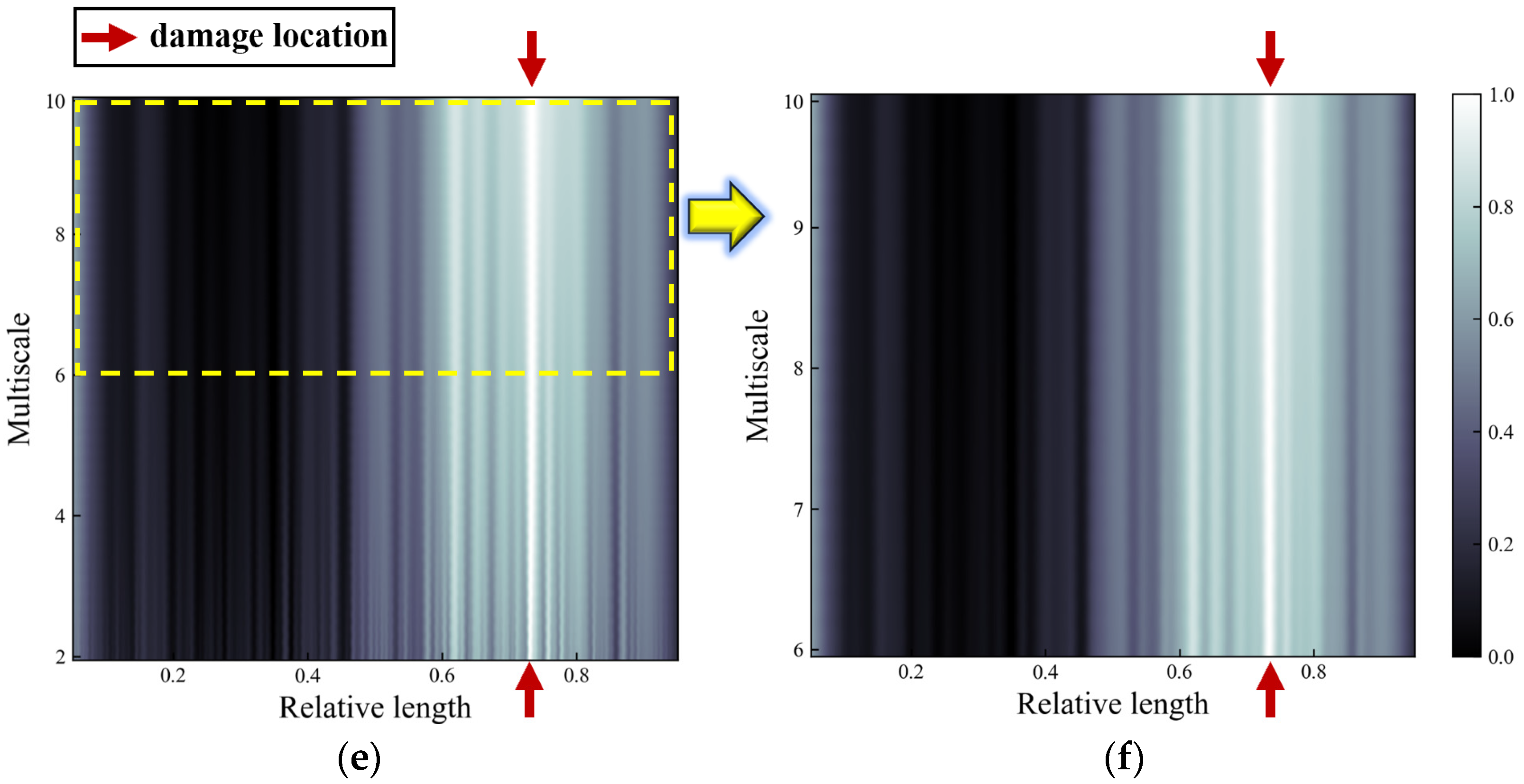

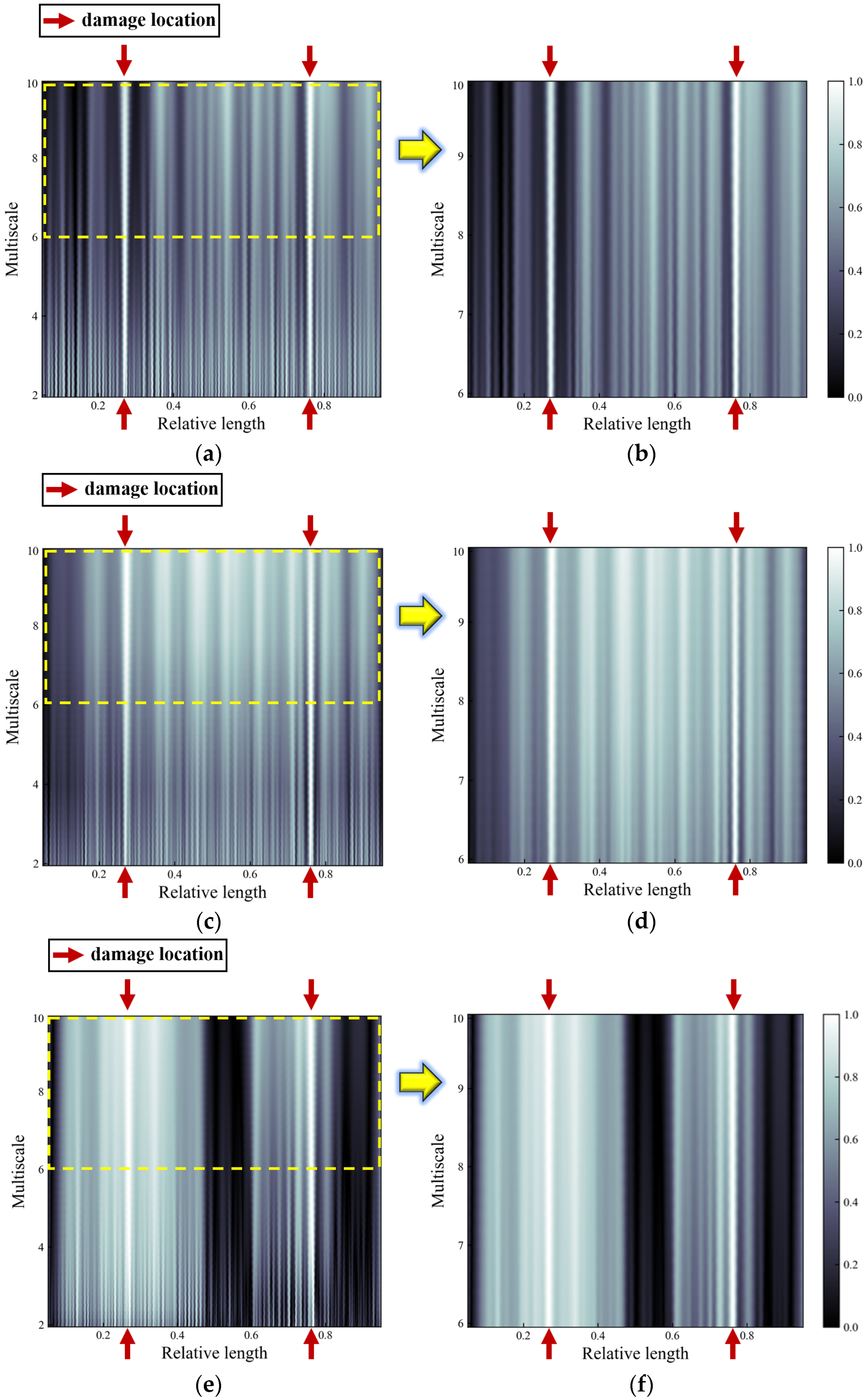

2.2. A Novel Damage Index: MS-LIE

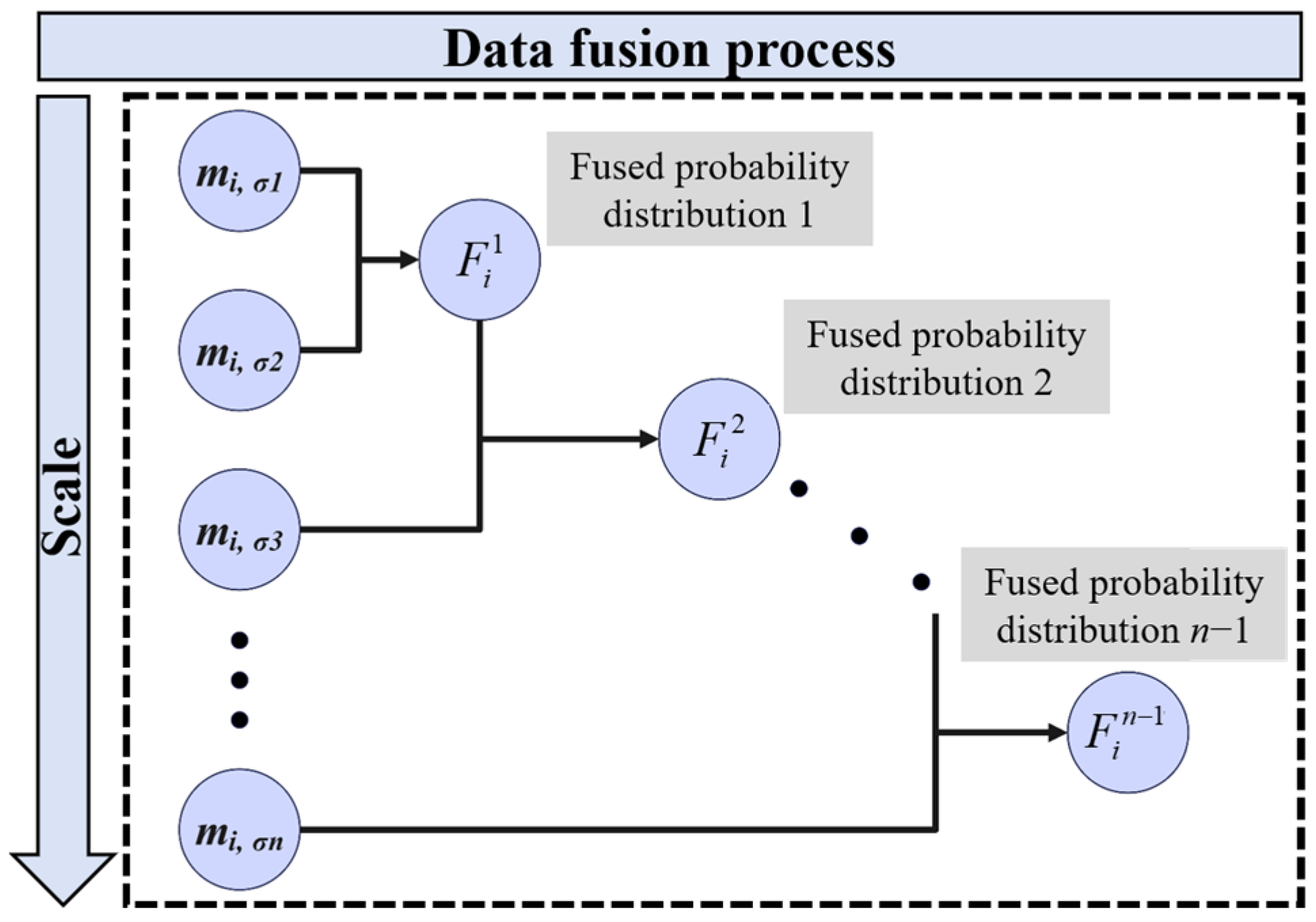

2.3. Data Fusion for Multi-Scale Damage Information

3. Numerical Investigations of the Methodology

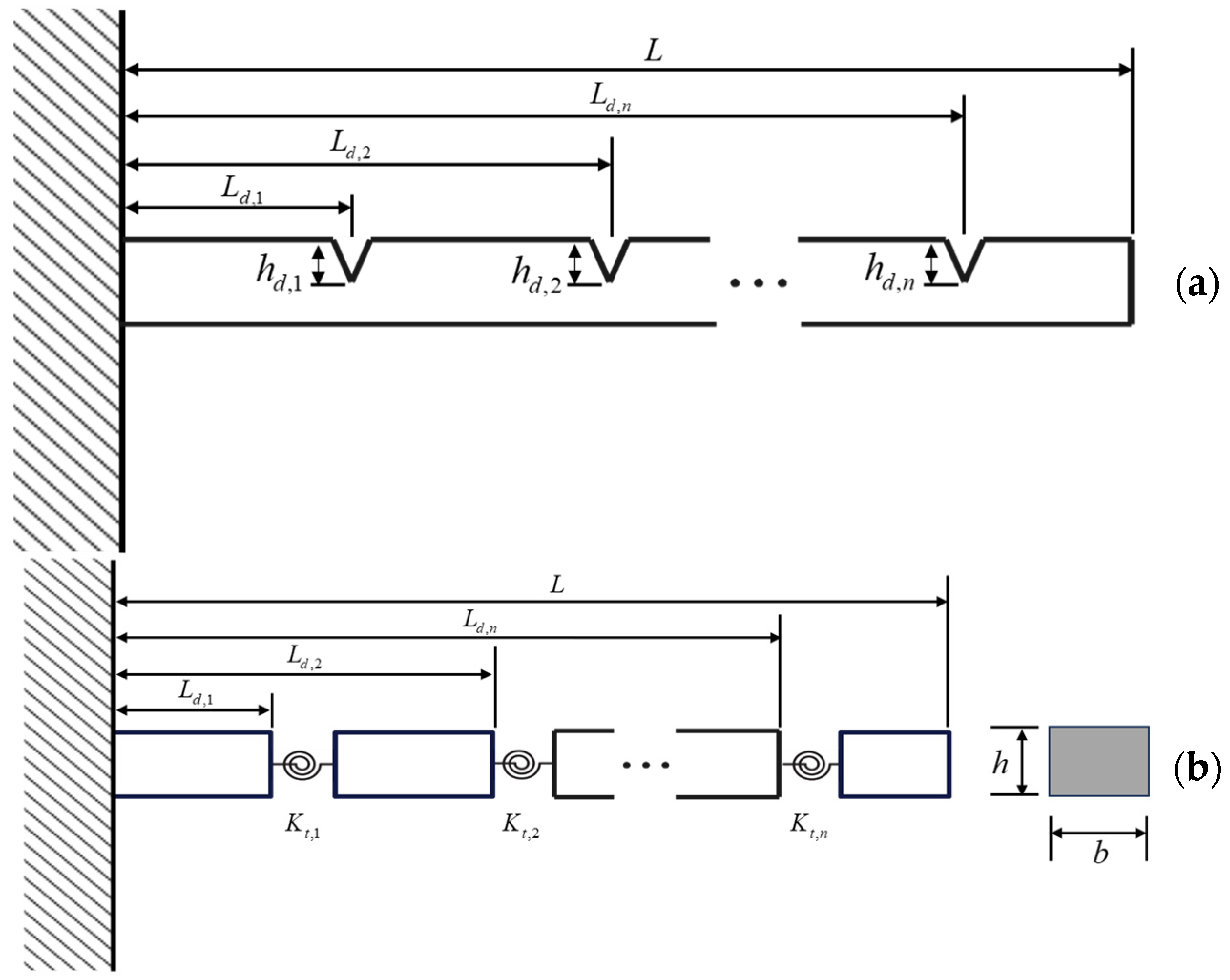

3.1. Analytical Model of Cracked Beam

3.2. Noise Immunity Evaluations

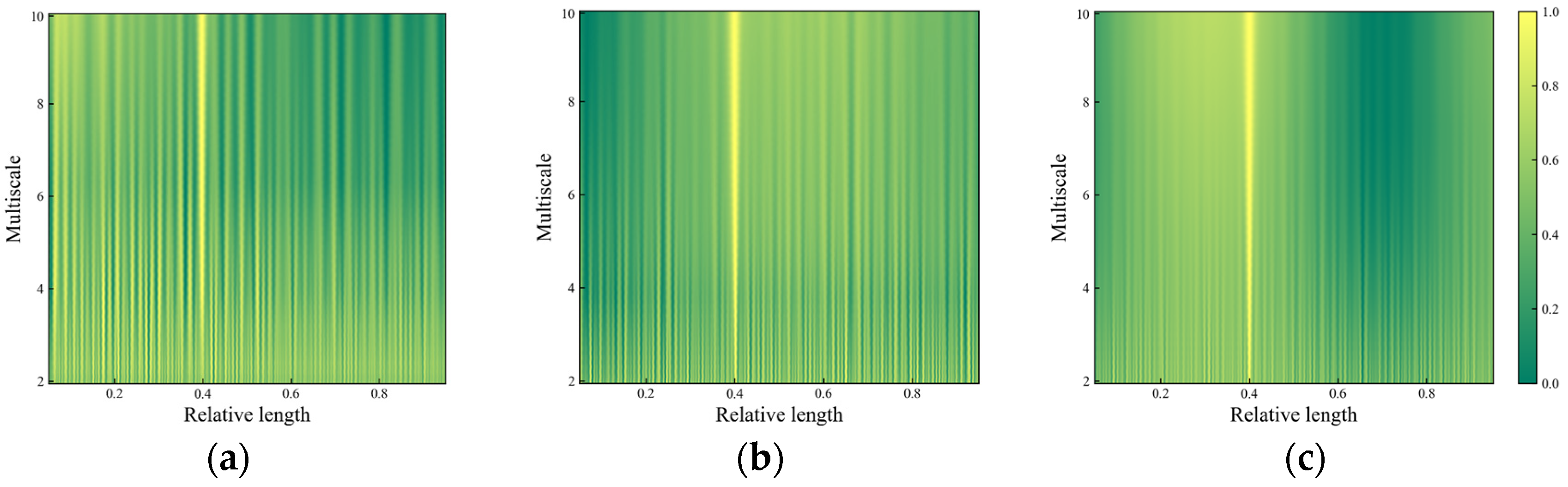

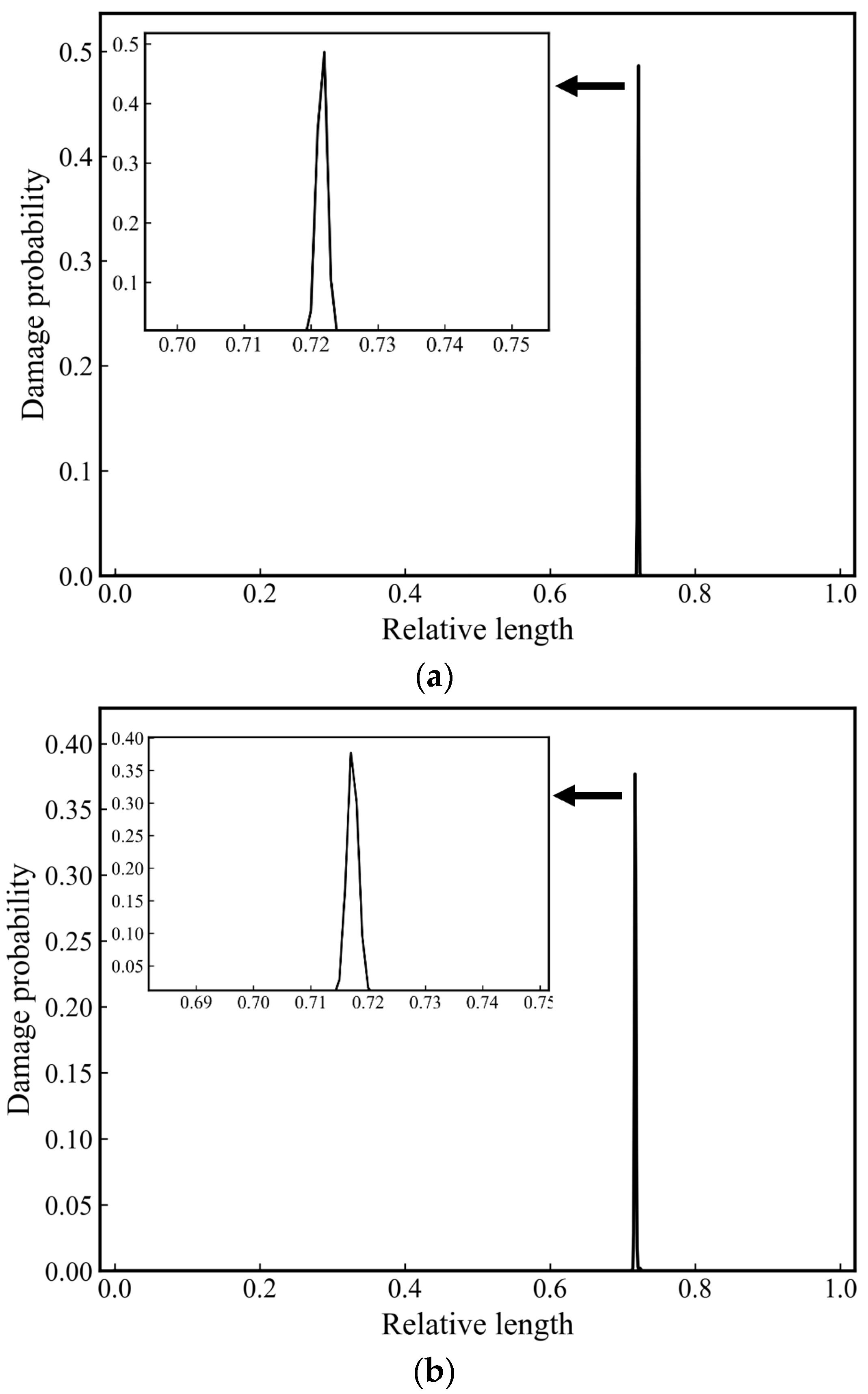

3.2.1. Evaluations on Single Damage

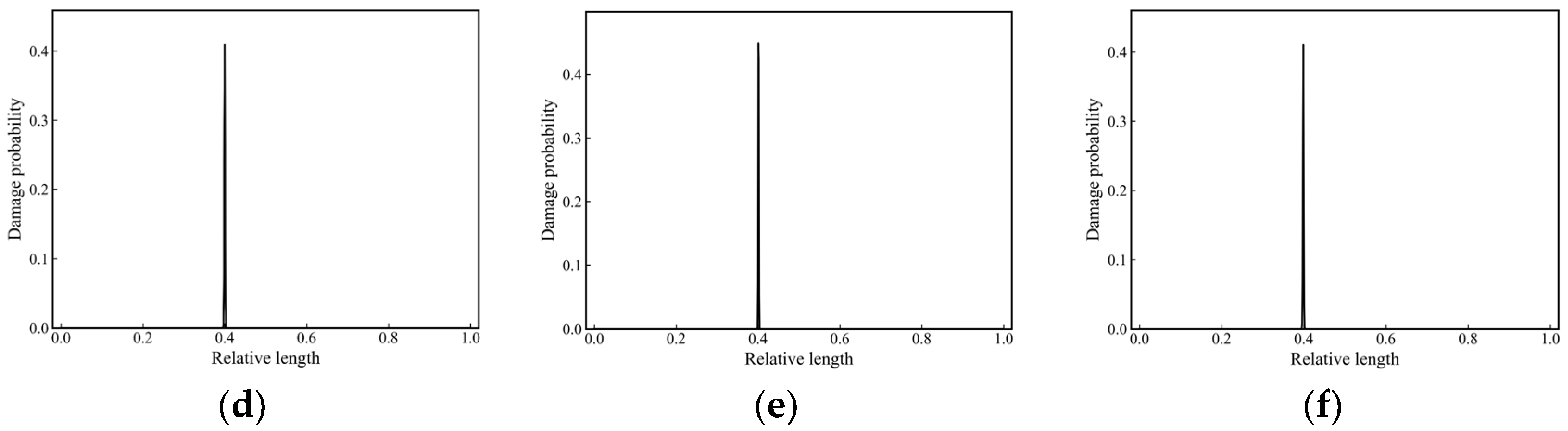

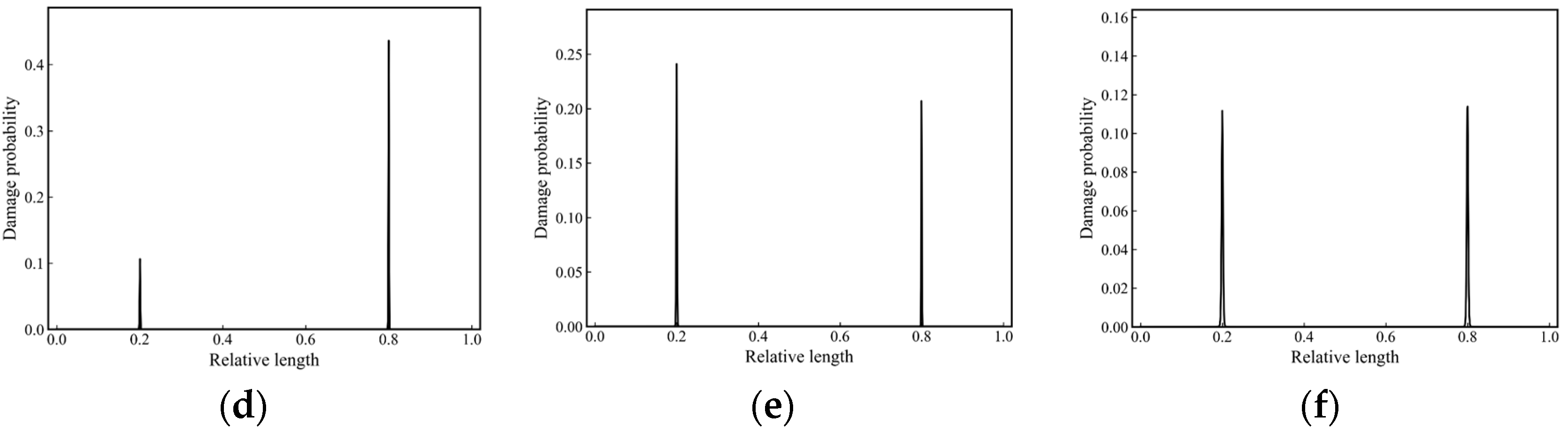

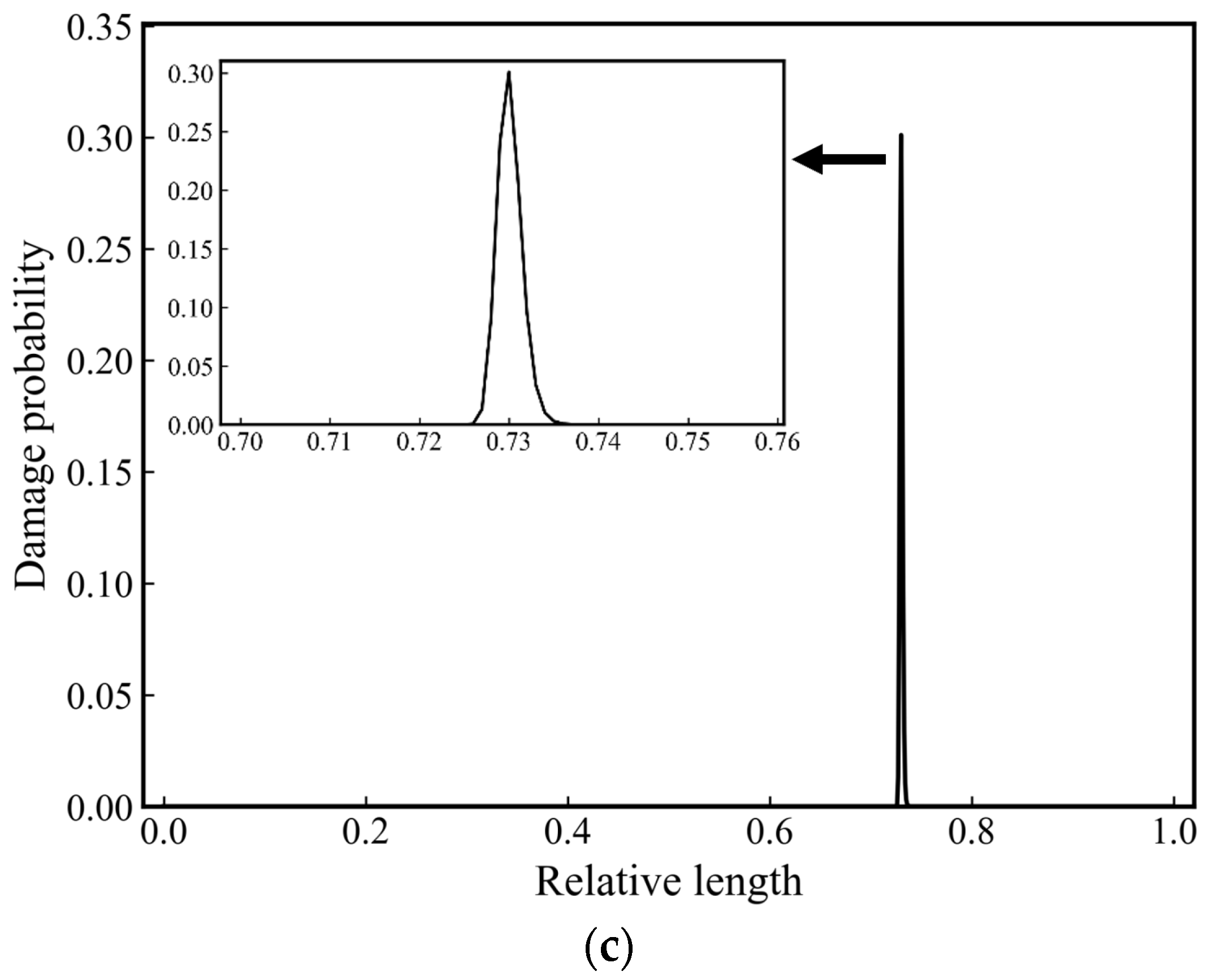

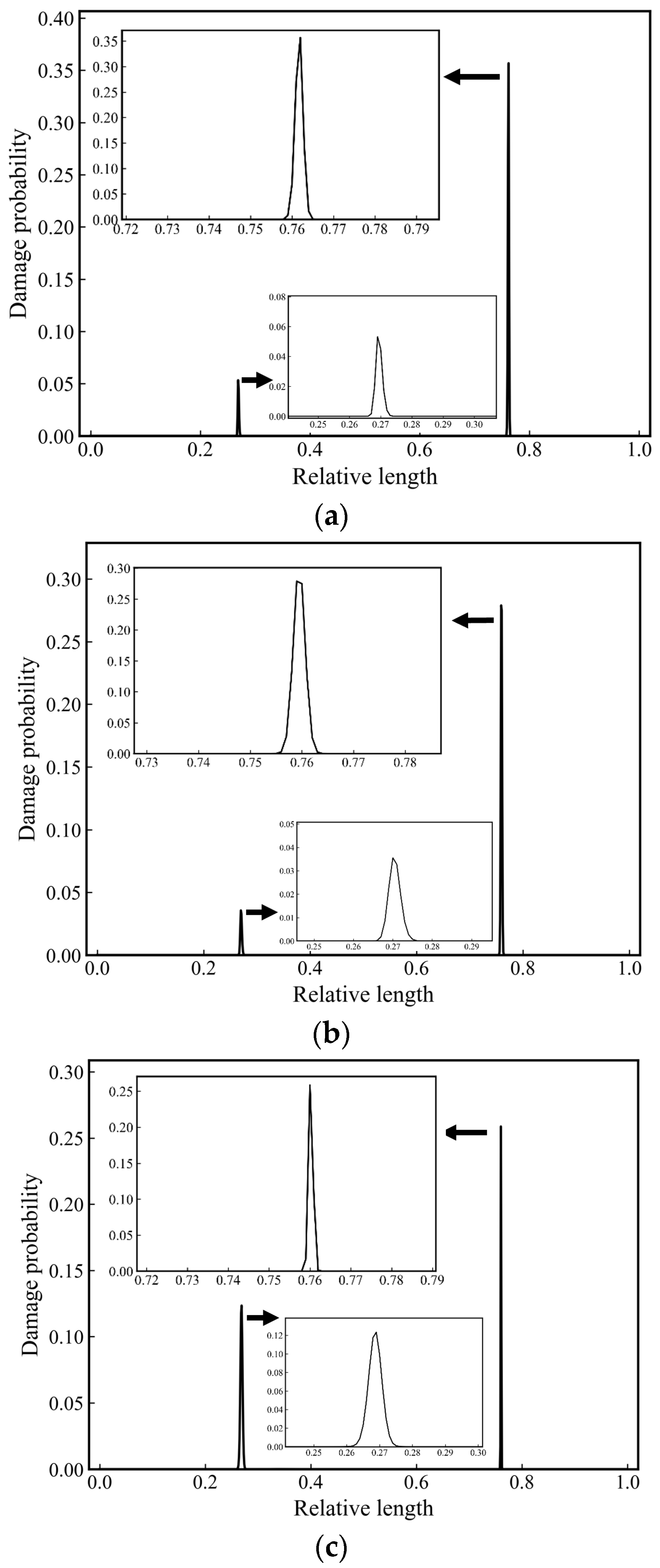

3.2.2. Evaluations on Double Damages

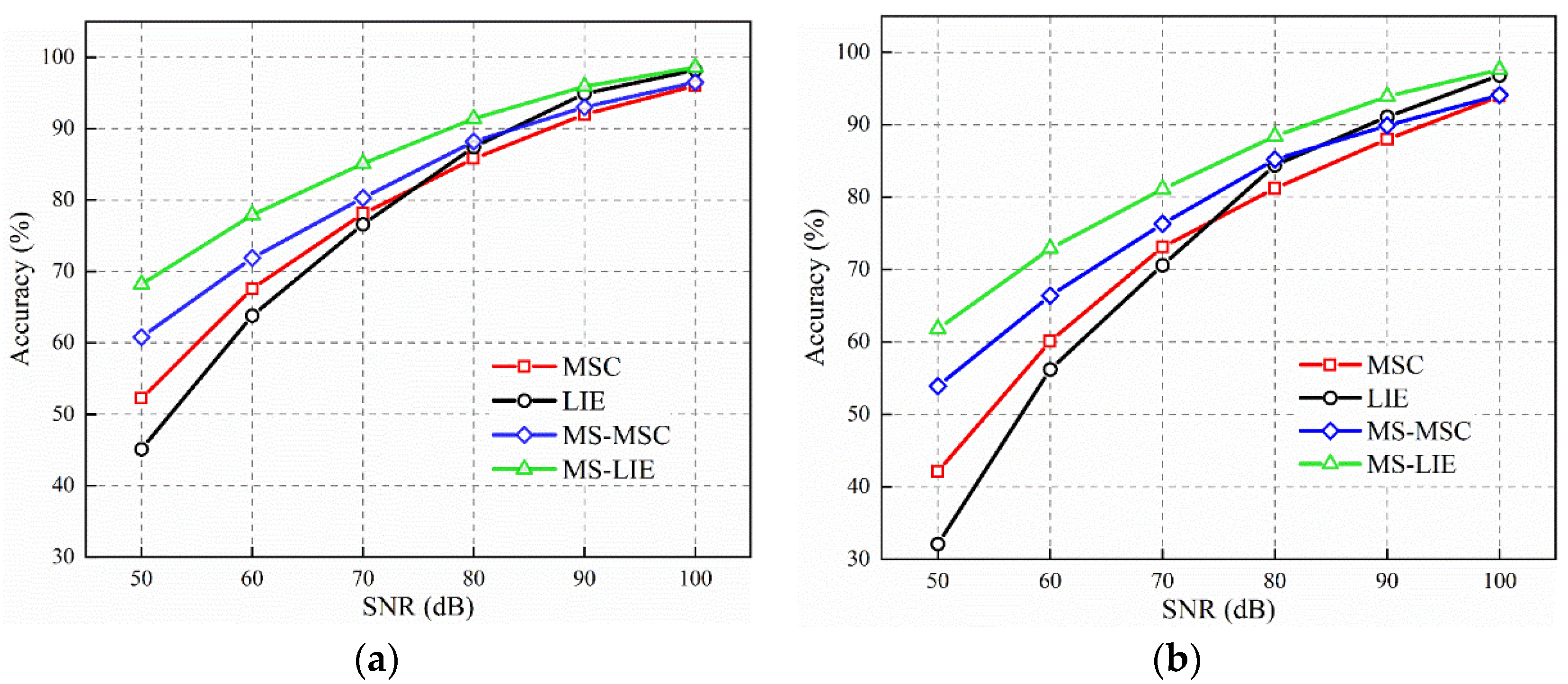

3.2.3. Compared with Other Methods

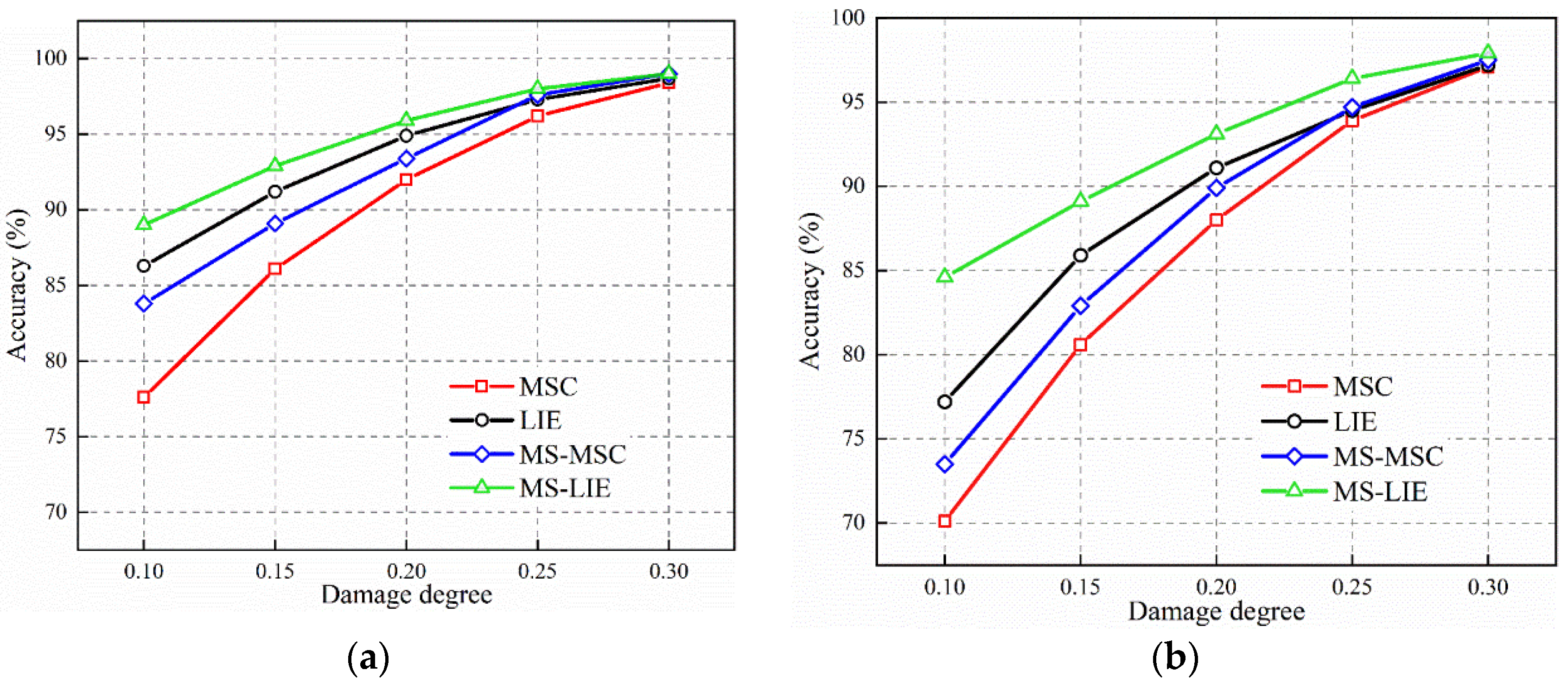

3.3. Ablation Study

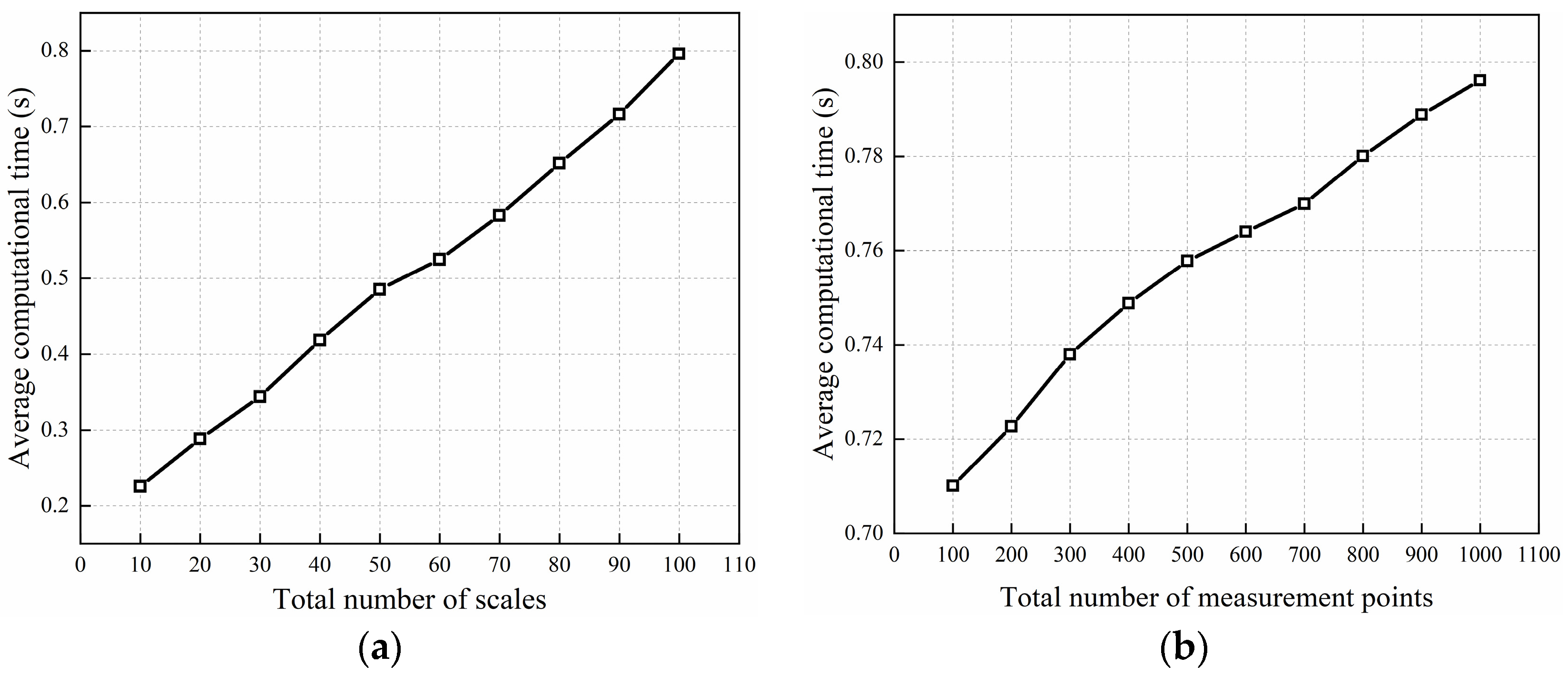

3.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

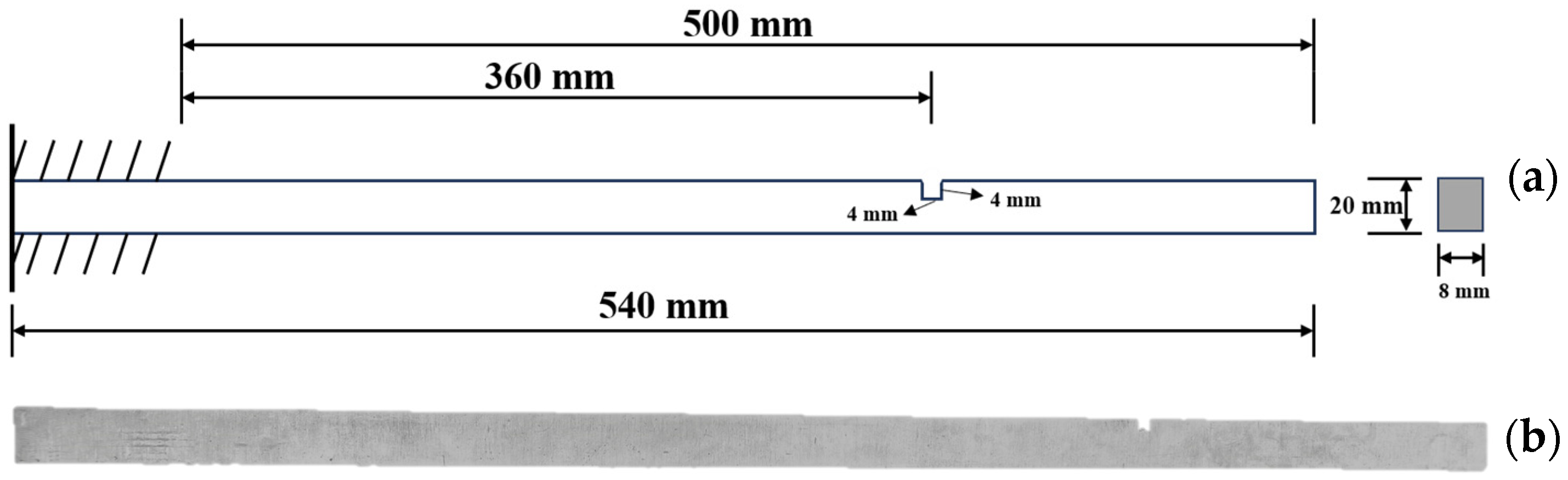

4. Experimental Verifications of the Methodology

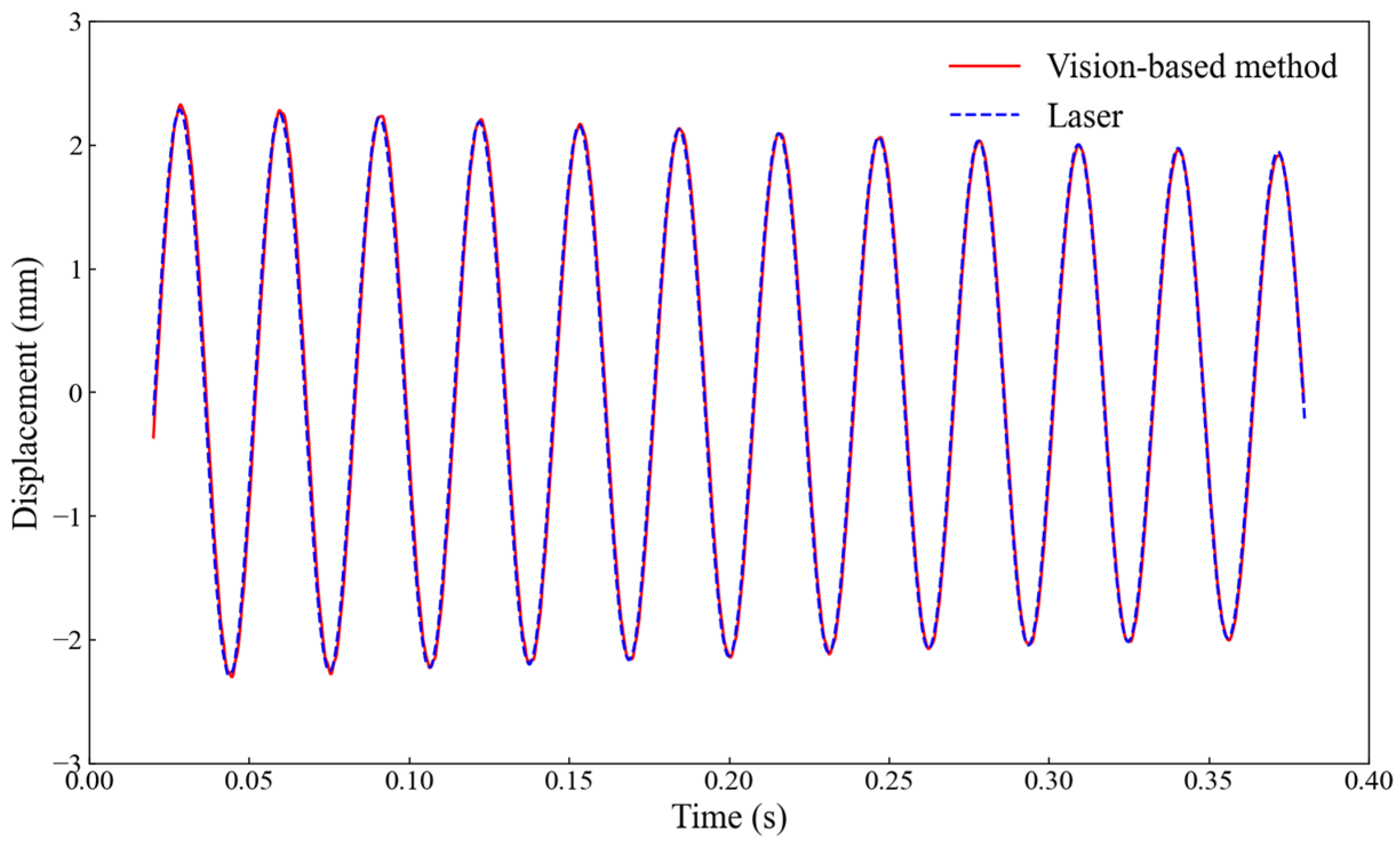

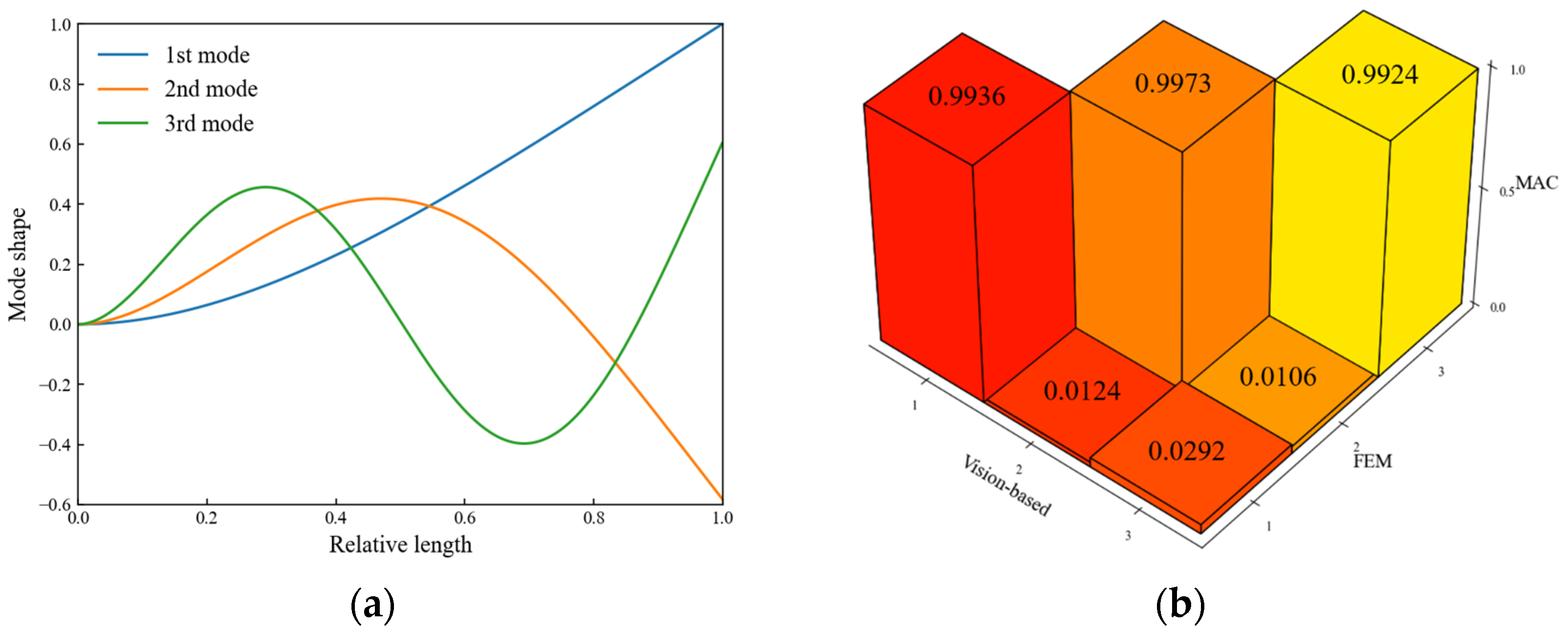

4.1. The Accuracy of Vibration Measurement

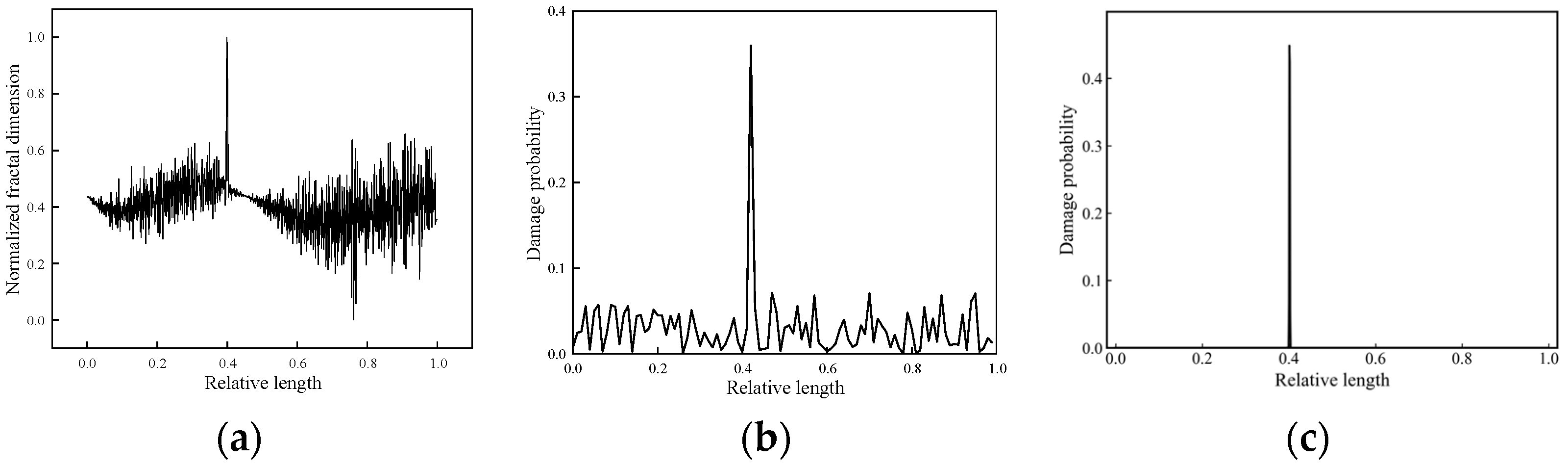

4.2. Detection of Single Damage

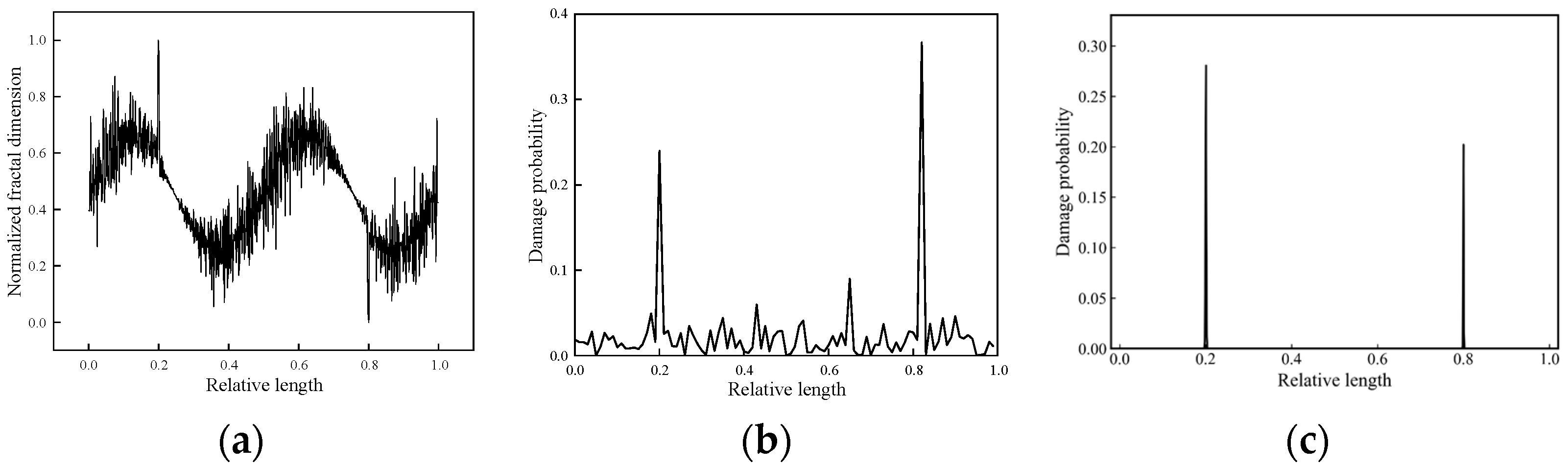

4.3. Detection of Double Damages

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The vibration signals obtained by phase-based optical flow estimation show good agreement with those from the laser vibrometer and FEM in terms of displacement, frequency, and mode shapes. This indicates that the vision-based method can deliver precise vibration measurements obviating the need for speckle patterns or high-contrast markers on the surface, and the high-spatial-resolution mode shapes provided by the vision-based method are reliable. The utilization of the phase-based optical flow estimation technique facilitates the implementation of a non-contact, non-destructive monitoring approach that can be applied to a diverse range of structures.

- (2)

- The novel damage index MS-LIE integrates the multi-scale analysis component and the entropy analysis component, addressing both the issue of detection sensitivity and noise immunity, thereby showcasing enhanced performance. The MS-LIE effectively reveals damage features in Gaussian multi-scale space, even in the presence of noise. Benefiting from utilizing damage evidence across all scales through data fusion technique, the proposed method demonstrates robustness in detecting damage under various noisy environments. The final damage probability distributions accurately identify instances of single and multiple damages without the necessity of a baseline data set as a reference.

- (3)

- The results of the ablation study have demonstrated the utility of entropy-based and multi-scale analysis-based approaches in SHM. It can inform future research by encouraging the exploration of other entropy measures for damage detection and promoting the integration of advanced multi-scale analysis-based data fusion techniques to further enhance detection capabilities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nick, H.; Ashrafpoor, A.; Aziminejad, A. Damage identification in steel frames using dual-criteria vibration-based damage detection method and artificial neural network. Structures 2023, 51, 1833–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, A.; Hussain, Z.; Akbar, M.; Rabczuk, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, S.; Ahmed, B. Towards vibration-based damage detection of civil engineering structures: Overview, challenges, and future prospects. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2024, 20, 591–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, S.; Yang, B.; Wüchner, R.; Pan, L.; Zhu, H. Real-time structural health monitoring system based on streaming data. Smart Struct. Syst. 2021, 28, 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo, D.; Lara-Valencia, L.A.; Brito, J. Frequency-based methods for the detection of damage in structures: A chronological review. Dyna 2021, 88, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Ramakrishnan, K.R.; Singh, H.K. A novel method of vibration modes selection for improving accuracy of frequency-based damage detection. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 159, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, G.; Radzieński, M.; Cao, M.; Ostachowicz, W. A novel method for single and multiple damage detection in beams using relative natural frequency changes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 132, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Sha, G.; Gao, Y.; Ostachowicz, W. Structural damage identification using damping: A compendium of uses and features. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzarin, M.; Feng, M.Q.; Franchetti, P.; Soyoz, S.; Modena, C. Damage detection based on damping analysis of ambient vibration data. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2010, 17, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei Alavijeh, M.; Soorgee, M.H. A novel damping based feature for rich resin defect detection in a four layer composite plate using S0 Lamb mode. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2021, 36, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Wu, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z. Damage detection in a novel deep-learning framework: A robust method for feature extraction. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 19, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Wahab, M.A. Damage detection in slab structures based on two-dimensional curvature mode shape method and Faster R-CNN. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 176, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooya, S.M.H.; Massumi, A. A novel and efficient method for damage detection in beam-like structures solely based on damaged structure data and using mode shape curvature estimation. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 91, 670–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Xia, Y. Review on the new development of vibration-based damage identification for civil engineering structures: 2010–2019. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 491, 115741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ge, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, B.; Yan, K.; Fu, Y.; Yu, Q. Defects localization using the data fusion of laser Doppler and image correlation vibration measurements. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 160, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, I.; Damjanović, D.; Bartolac, M.; Skender, A. Mode shape-based damage detection method (MSDI): Experimental validation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Choi, J.; Sohn, H. Continuous bridge displacement estimation using millimeter-wave radar, strain gauge and accelerometer. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 197, 110408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Tang, W.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, D.; Huang, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, W.; Ma, S. The construction and comparison of damage detection index based on the nonlinear output frequency response function and experimental analysis. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 427, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K. Structural damage identification using mode shape slope and curvature. J. Eng. Mech. 2017, 143, 04017110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, A.; Jane Regita, J.; Rane, B.; Lau, H.H. Structural health monitoring using wireless smart sensor network—An overview. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 163, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dorn, C.; Mancini, T.; Talken, Z.; Theiler, J.; Kenyon, G.; Farrar, C.; Mascareñas, D. Reference-free detection of minute, non-visible, damage using full-field, high-resolution mode shapes output-only identified from digital videos of structures. Struct. Health Monit. 2018, 17, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.B.; Chen, X.F.; Xie, Y.; Miao, H.-H.; Gao, J.-J.; Qi, K.-Z. Hybrid two-step method of damage detection for plate-like structures. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2016, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Xu, Z. Structural health monitoring using DOG multi-scale space: An approach for analyzing damage characteristics. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Cai, E. Structural displacement estimation by a hybrid computer vision approach. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 204, 110754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Niu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhong, Z.; Huang, J.; Shan, M. Fast and accurate visual vibration measurement via derivative-enhanced phase-based optical flow. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 209, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Kong, Y.; Nam, H.; Lee, S.; Park, G. Phase-based vibration imaging for structural dynamics applications: Marker-free full-field displacement measurements with confidence measures. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 198, 110418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, S. Damage detection of structures from motion videos using high-spatial-resolution mode shapes and data fusion. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Li, D.; Chen, W.; Deng, L.; Jiang, X. Mode shape–aided cable force determination using digital image correlation. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 20, 2430–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqersad, J.; Niezrecki, C.; Avitabile, P. Extracting full-field dynamic strain on a wind turbine rotor subjected to arbitrary excitations using 3D point tracking and a modal expansion technique. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 352, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chan, I.; Brilakis, I. Shifting research from defect detection to defect modeling in computer vision-based structural health monitoring. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Nishio, M. Review for vision-based structural damage evaluation in disasters focusing on nonlinearity. Smart Struct. Syst. 2024, 33, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jin, T.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W. A review of computer vision-based structural deformation monitoring in field environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q. Optimal aperture and digital speckle optimization in digital image correlation. Exp. Mech. 2021, 61, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Pan, B. Overview of High-temperature Deformation Measurement Using Digital Image Correlation. Exp. Mech. 2021, 61, 1121–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dorn, C.; Mancini, T.; Talken, Z.; Kenyon, G.; Farrar, C.; Mascareñas, D. Blind identification of full-field vibration modes from video measurements with phase-based video motion magnification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 85, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, S.; Dare, T. Accuracy of phase-based optical flow for vibration extraction. J. Sound Vib. 2022, 535, 117112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Wadhwa, N.; Cha, Y.-J.; Durand, F.; Freeman, W.T.; Buyukozturk, O. Modal identification of simple structures with high-speed video using motion magnification. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 345, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrafi, A.; Mao, Z.; Niezrecki, C.; Poozesh, P. Vibration-based damage detection in wind turbine blades using Phase-based Motion Estimation and motion magnification. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 421, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Qin, M.; He, M.; Xu, Z. An approach for damage detection in noisy environments using DOG multi-scale space and fractal dimension. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2023, 38, 767–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Nagarajaiah, S. Blind modal identification of output-only structures in time-domain based on complexity pursuit. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2013, 42, 1885–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, S.F.; Modarres, M.; Bruck, H.A. A new method for detecting fatigue crack initiation in aluminum alloy using acoustic emission waveform information entropy. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 223, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, T. Scale-space theory: A basic tool for analyzing structures at different scales. J. Appl. Stat. 1994, 21, 225–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Ju, Y.; Bao, J.; Lyu, W. Multisensor fusion method based on the belief entropy and DS evidence theory. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 7917512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamnios, Y.; Douka, E.; Trochidis, A. Crack identification in beam structures using mechanical impedance. J. Sound Vib. 2002, 256, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Radzieński, M.; Xu, W.; Ostachowicz, W. Identification of multiple damage in beams based on robust curvature mode shapes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2014, 46, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1st Frequency/Hz | FEM | 33.96 |

| Laser | 33.44 | |

| Vision | 33.36 | |

| 2nd Frequency/Hz | FEM | 213.32 |

| Laser | 212.45 | |

| Vision | 212.55 | |

| 3rd Frequency/Hz | FEM | 597.48 |

| Laser | 596.46 | |

| Vision | 596.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.; Xin, C. Vision-Based Damage Detection Method Using Multi-Scale Local Information Entropy and Data Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020803

Zhang Y, Xu Z, Li G, Xin C. Vision-Based Damage Detection Method Using Multi-Scale Local Information Entropy and Data Fusion. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(2):803. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020803

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yiming, Zili Xu, Guang Li, and Cun Xin. 2025. "Vision-Based Damage Detection Method Using Multi-Scale Local Information Entropy and Data Fusion" Applied Sciences 15, no. 2: 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020803

APA StyleZhang, Y., Xu, Z., Li, G., & Xin, C. (2025). Vision-Based Damage Detection Method Using Multi-Scale Local Information Entropy and Data Fusion. Applied Sciences, 15(2), 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020803