Enhanced Control Strategy for Three-Level T-Type Converters in Hybrid Power-to-X Systems

Abstract

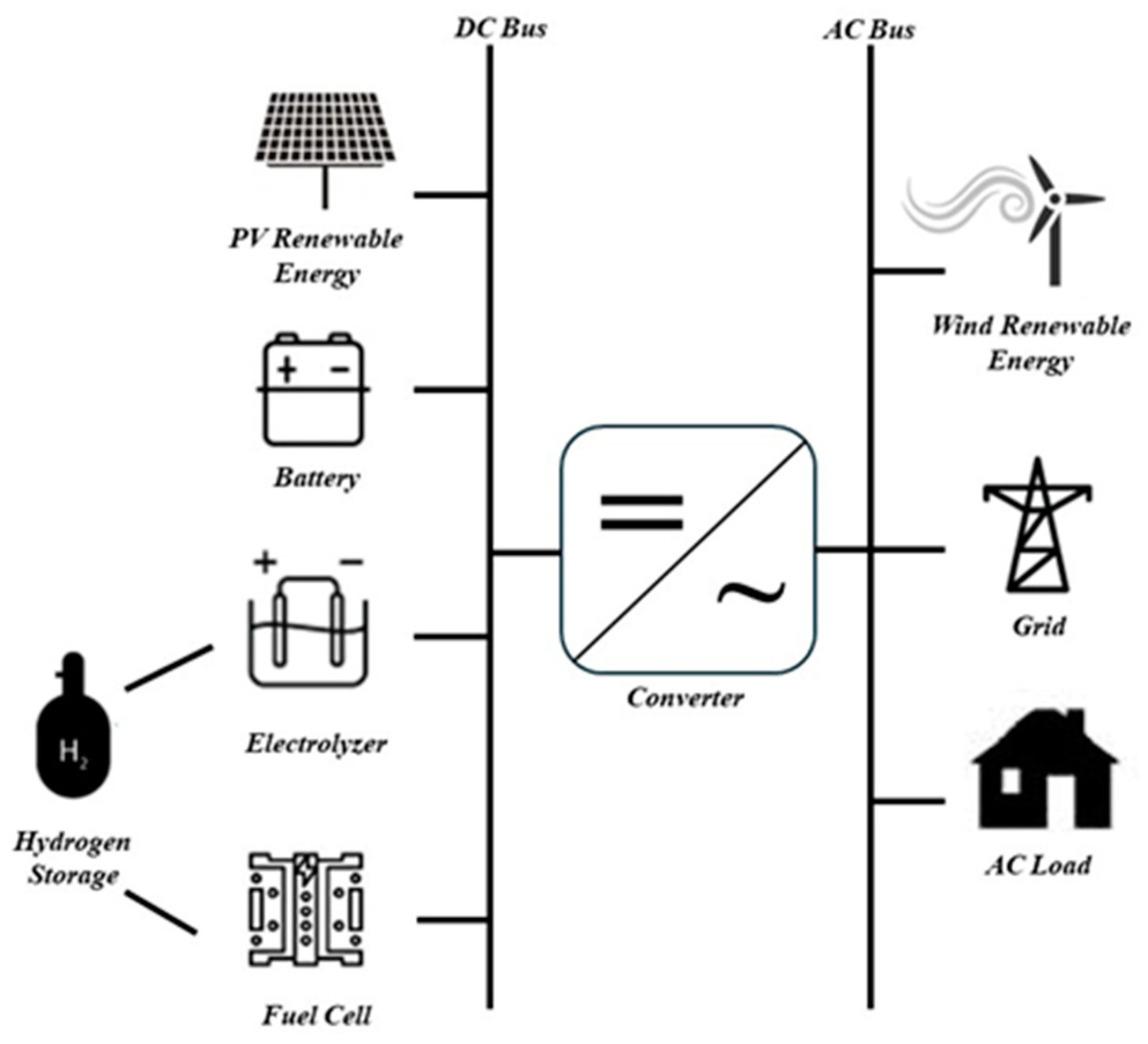

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Survey

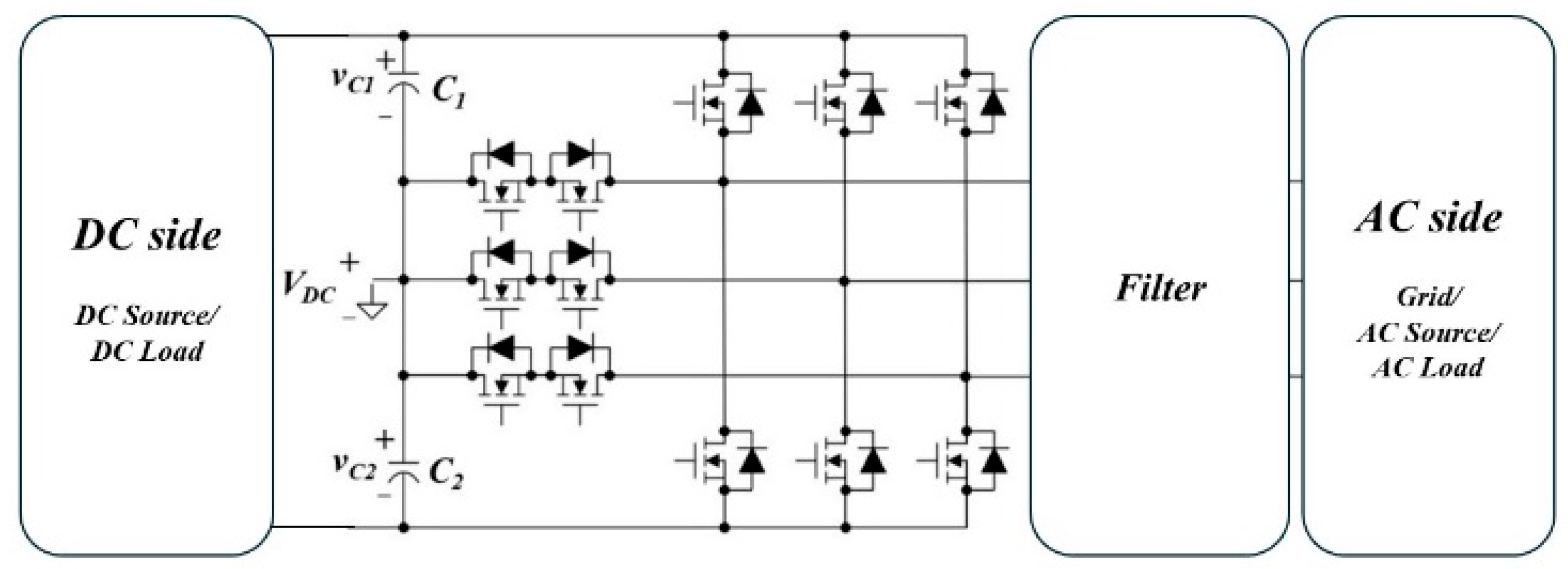

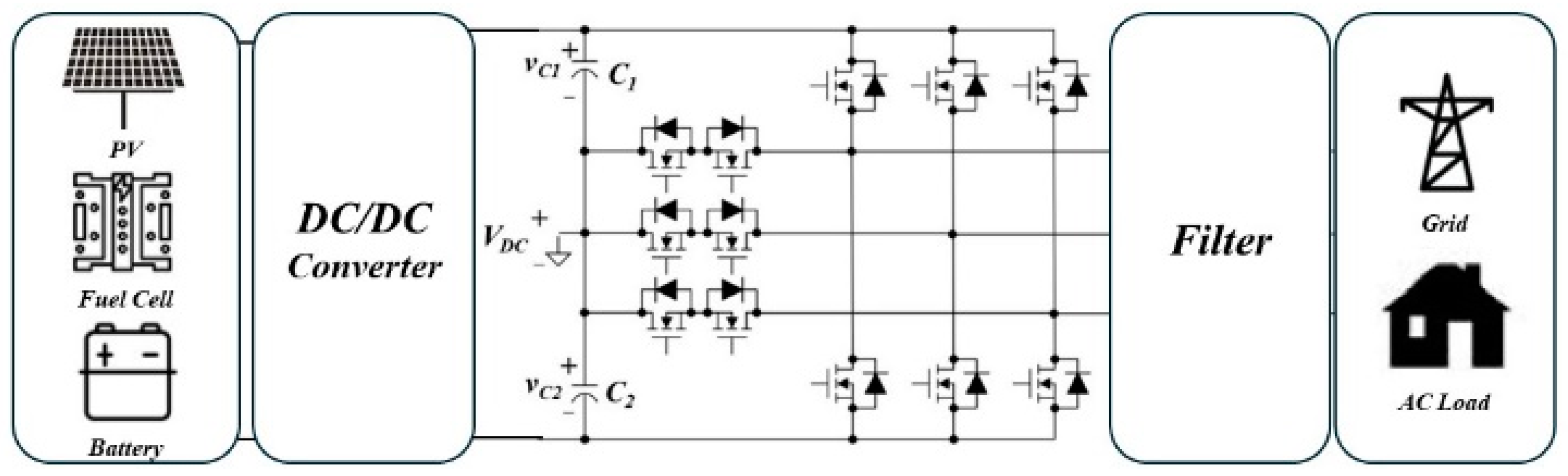

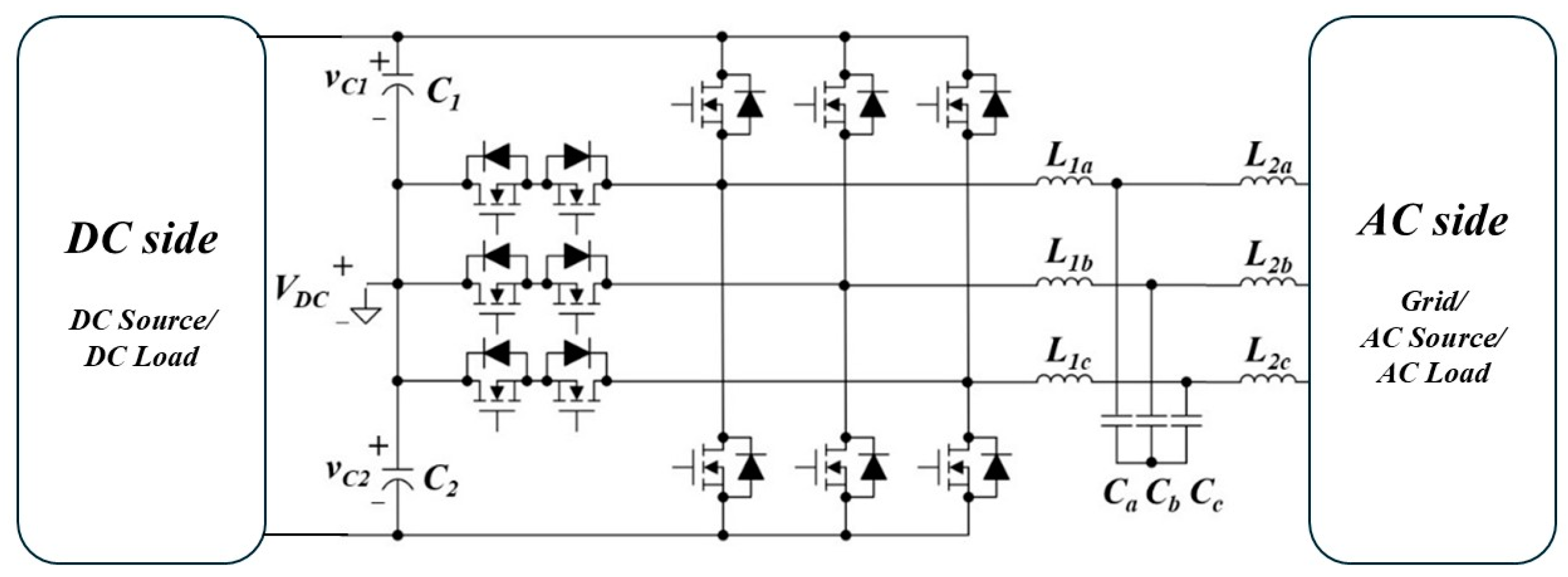

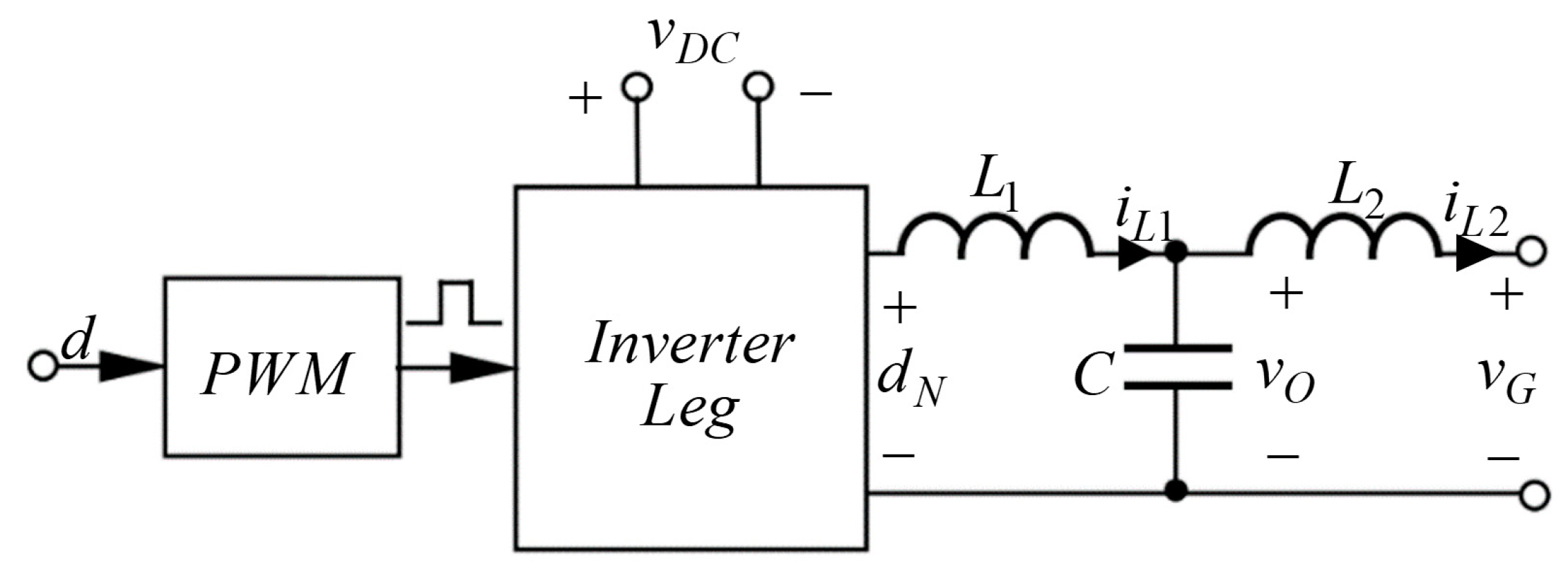

3. Three-Phase T-Type Bidirectional Converter

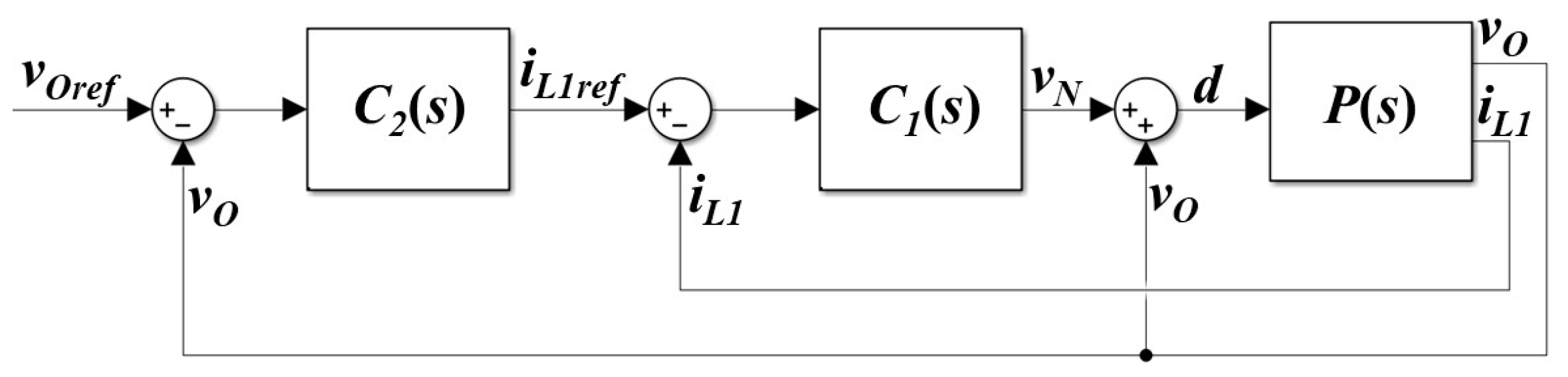

4. Proposed Control Design

4.1. Feed-Forward Capacitor Voltage Loop

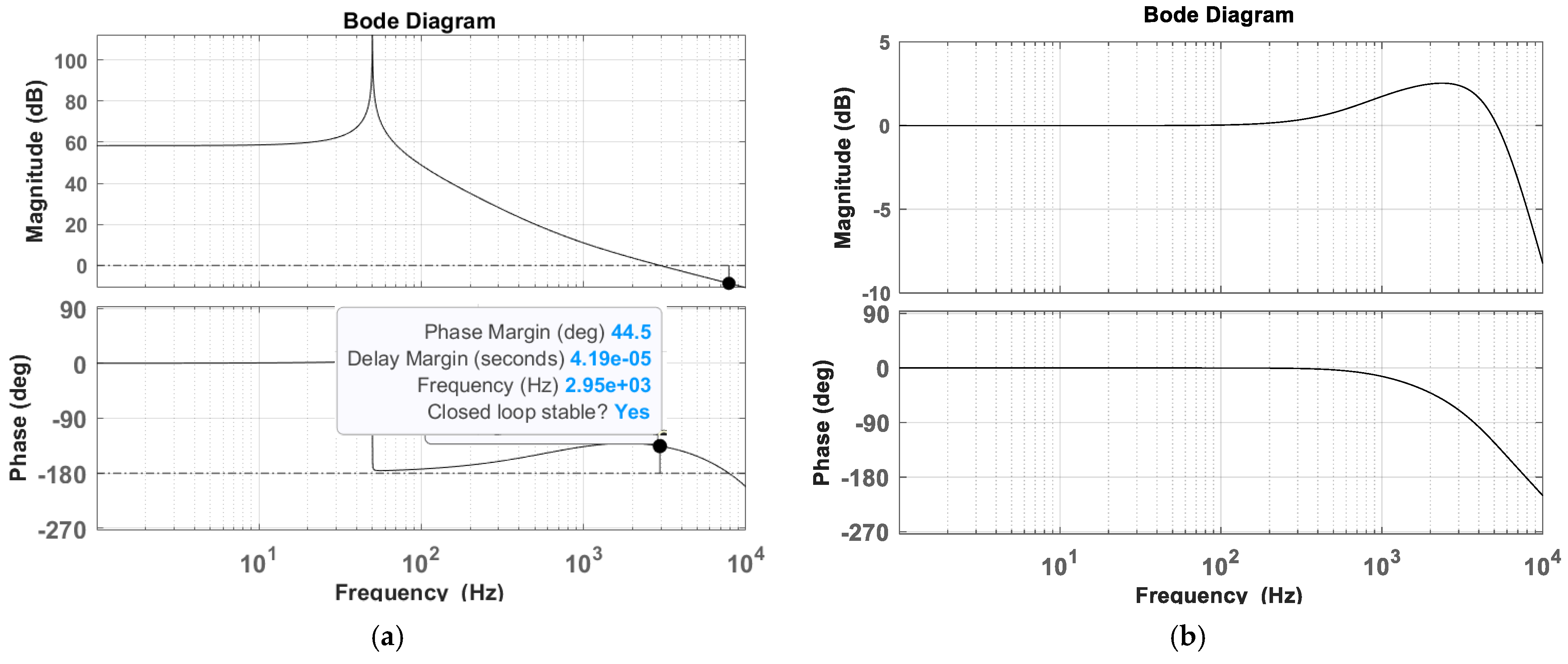

4.2. Inverter Side Inductor Inner Control Loop

- -

- Specify the target phase margin PM of the inner current loop;

- -

- Determine the delay value Td according to the switching frequency (Td~1.5 Ts);

- -

- Set the value of crossover frequency ωBI according to (18) and (20);

- -

- Set the value of ξ to be between 0.01–0.001;

- -

- Shape the controller and loop gain according to (12) and (13), respectively.

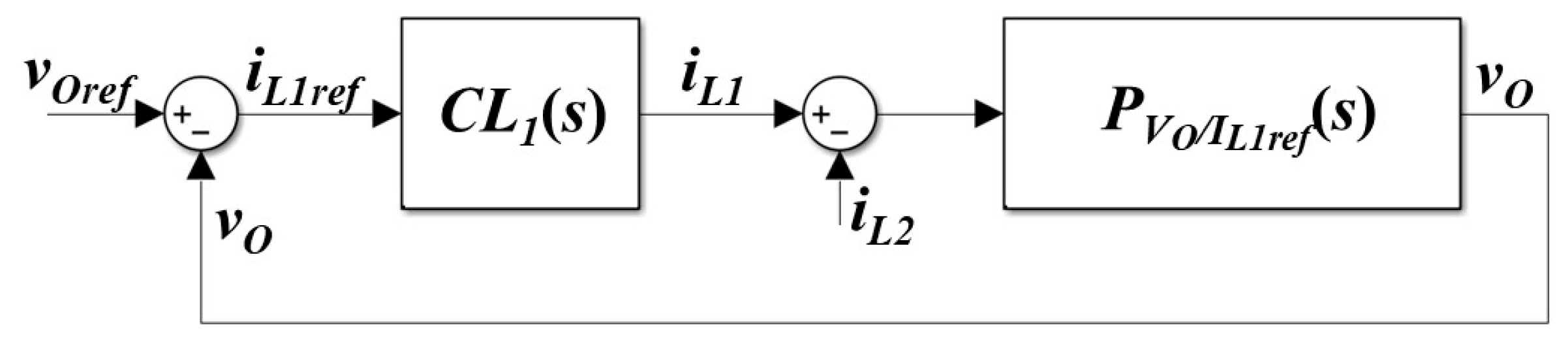

4.3. Output Voltage Outer Control Loop

- -

- Specify the target phase margin PM of the voltage loop;

- -

- Determine the delay value Td according to the Bode diagram of a current closed loop;

- -

- Set the value of crossover frequency ωBV according to (28) and (29);

- -

- Set the value of ξ to be between 0.01–0.001;

- -

- Shape the controller and loop gain according to (23) and (27), respectively.

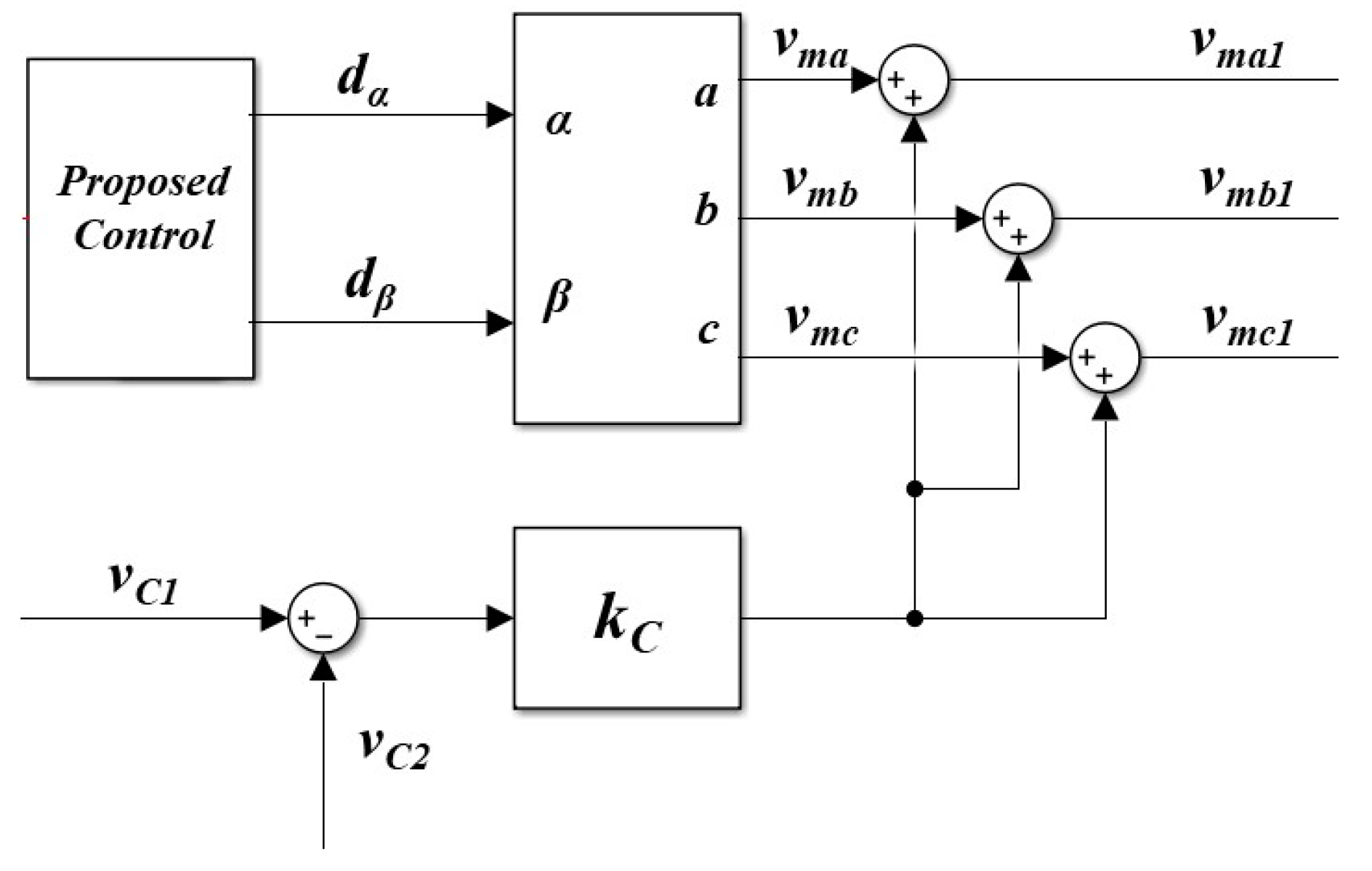

4.4. DC-Link Capacitors Voltage Balancing Control

5. Verification

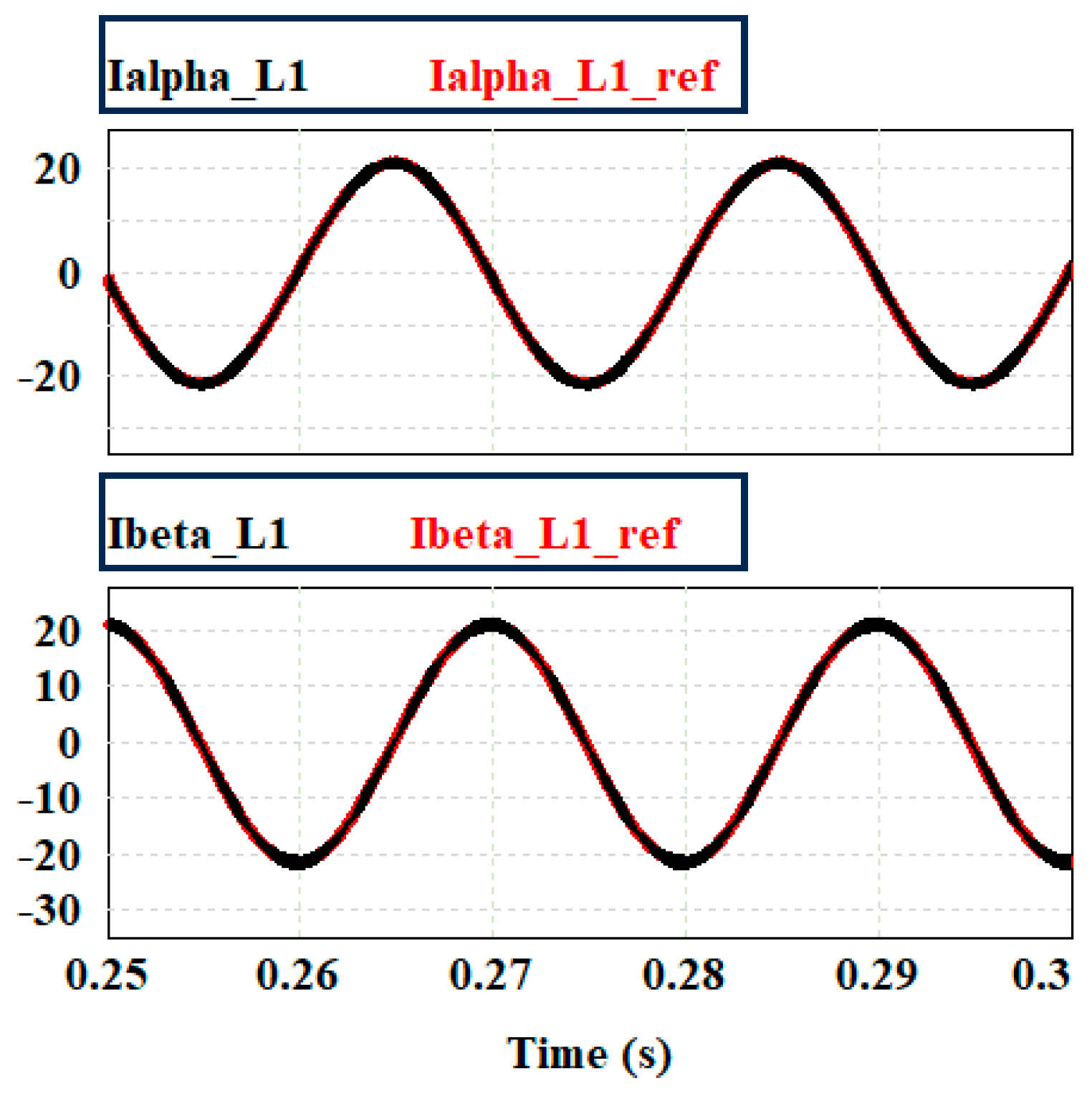

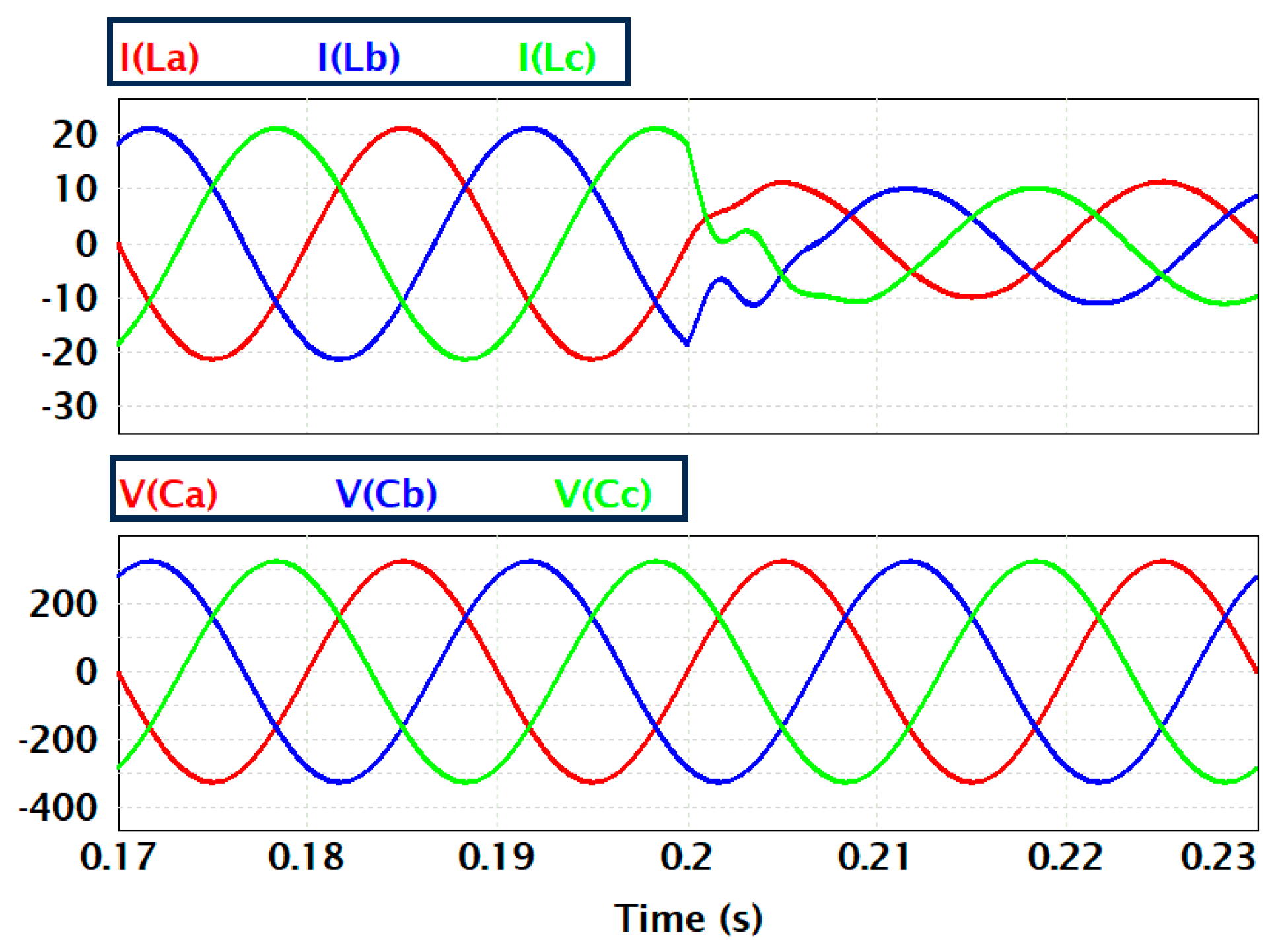

5.1. Simulation Validation

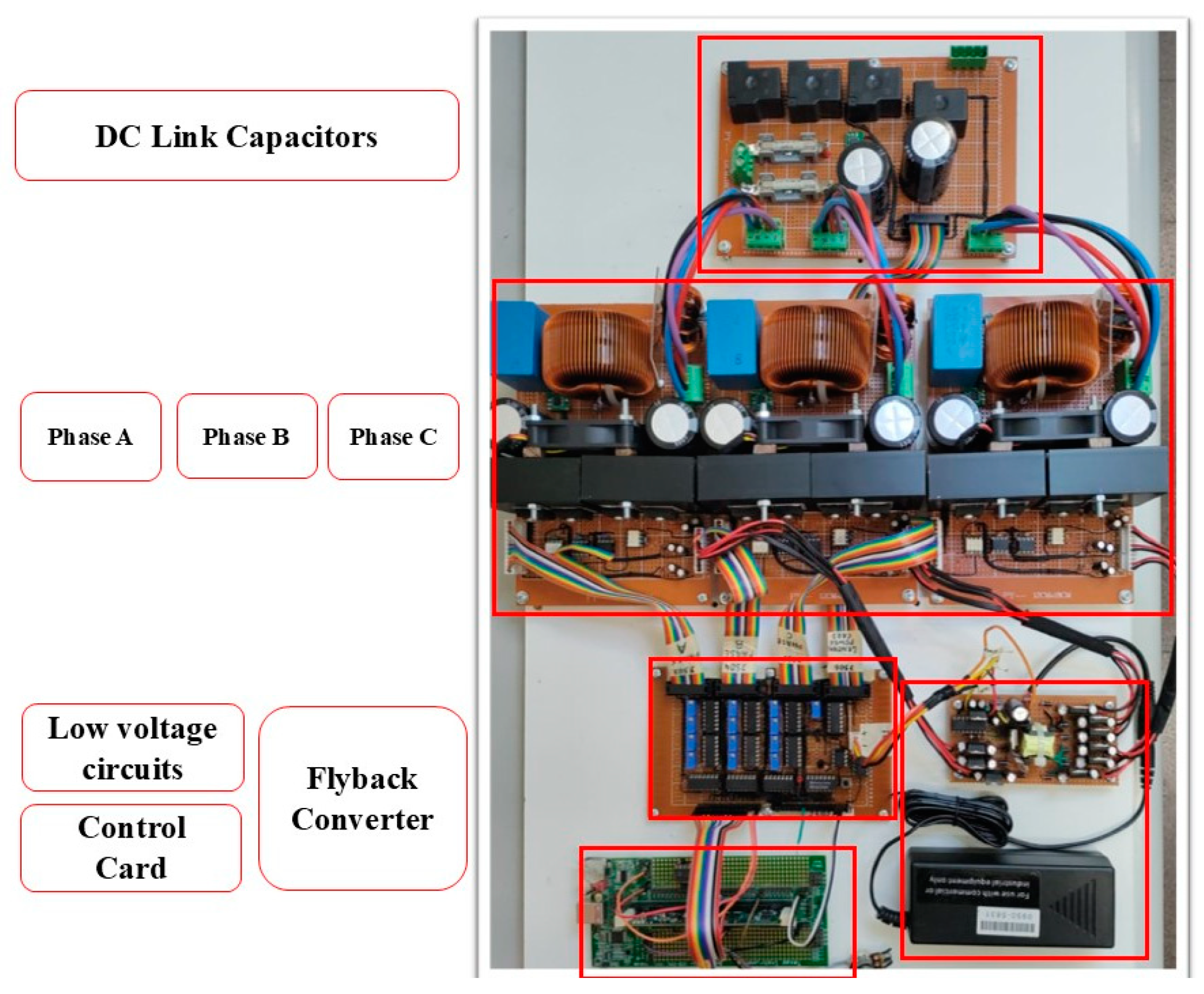

5.2. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Lu, Y. Control Strategy Based on the Flexible Multi-State Switch for Maximum Consumption of Distributed Generations in Distribution Network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M.; Khan, M.A.; Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M.; Jamal, M.A. Comprehensive techno-economic analysis of a standalone renewable energy system for simultaneous electrical load management and hydrogen generation for fuel cell electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 6255–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausell, E.; Navarro, G.; Lafoz, M.; Arnaltes, S.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Blanco, M. Analysis of using MMC topologies for the direct integration of renewable generation with modular electrolyzers. In Proceedings of the 2023 25th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’23 ECCE Europe), Aalborg, Denmark, 4–8 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chou, S.-F.; Blaabjerg, F.; Davari, P. Overview of power electronic converter topologies enabling large-scale hydrogen production via water electrolysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Lin, J.; Song, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Mu, S.; Hu, Q. Modeling and operation of the power-to-gas system for renewables integration: A review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 4, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nady, S.; El Fadil, H.; Koundi, M.; Hamed, A.; Giri, F. Power to X systems: State-of-the-art. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, E.; Brumana, G.; Franchini, G.; Aristolao, N.; Vedovati, G. The role of hydrogen storage and electric vehicles in grid-isolated hybrid energy system with high penetration of renewable. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibiloni, S.; Irimescu, A.; Martinez-Boggio, S.; Merola, S.; Curto-Risso, P. Mild Hybrid Powertrain for Mitigating Loss of Volumetric Efficiency and Improving Fuel Economy of Gasoline Vehicles Converted to Hydrogen Fueling. Machines 2024, 12, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuskanen, V.; Koponen, J.; Kosonen, A.; Hehemann, M.; Keller, R.; Niemelä, M.; Ahola, J. Power quality estimation of water electrolyzers based on current and voltage measurements. J. Power Sources 2020, 450, 227603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vule, Y.; Siton, Y.; Kuperman, A. Comprehensive modeling and formulation of split DC link capacitors balancing problem in three-phase three-level bidirectional AC/DC converters operating with arbitrary power factor. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 83, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, T.; Liu, C. An Islanding Signal-Based Smooth Transition Control in AC/DC Hybrid Micro-Grids. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, M.; Kolar, J.W. Design and implementation of a highly efficient threelevel T-type converter for low-voltage applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floricau, D.; Floricau, E.; Gateau, G. Three-level active NPC converter: PWM strategies and loss distribution. In Proceedings of the 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics (IEEE IEAC), Orlando, FL, USA, 10–13 November 2008; pp. 3333–3338. [Google Scholar]

- Nabae, A.; Takahashi, I.; Akagi, H. A new neutral-point-clamped PWM inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1981, IA-17, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbi, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Poorfakhraei, A.; Vahedi, H.; Guse, M.; Trabelsi, M.; Abdelrahem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Fahad, M.; Lin, C.-H.; et al. Common DC-Link Multilevel Converters: Topologies, Control and Industrial Applications. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2023, 4, 512–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimel, D.; Barbie, E.; Bronshtein, S.; Sitbon, M.; Aharon, I.; Kuperman, A. High power T-type-based multi-level inverter for electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2023, 9 (Suppl. S12), 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulmrharj, S.; Khaidar, M.; Bakhouya, M.; Ouladsine, R.; Siniti, M.; Zine-Dine, K. Performance assessment of a hybrid system with hydrogen storage and fuel cell for cogeneration in buildings. Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkayam, M.; Kuperman, A. Optimized design of multiresonant AC current regulators for single-phase grid-connected photovoltaic inverters. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2019, 9, 1815–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, M.; Schacham, S.; Kuperman, A. Disturbance Observer-Based Voltage Regulation of Current-Mode-Boost-Converter-Interfaced Photovoltaic Generator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 5776–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busada, C.A.; Jorge, S.G.; Leon, A.E.; Solsona, J.A. Current controller based on reduced order generalized integrators for distributed generation systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 2898–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Dou, S.; Gillbanks, J.; Zhao, X. Active Disturbance Rejection Control Based on an Improved Topology Strategy and Padé Approximation in LCL-Filtered Photovoltaic Grid-Connected Inverters. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg; Teodorescu, R.; Liserre, M.; Timbus, A. Overview of control and grid synchronization for distributed power generation systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2006, 53, 1398–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Turégano, J.; Sala, A.; Blasco-Gimenez, R.; Blanes, C. Operation of DR–HVdc-Connected Grid-Forming Wind Turbine Converters Using Robust Loop-Shaping Controllers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman, A. Synchronous frame current controllers design based on desired stationary frame transient performance. Electron. Lett. 2015, 51, 1769–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Ishizuka, T.; Nezu, K.; Kataoka, T. A new control strategy for voltage-type PWM rectifiers to realize zero steady-state control error to input current. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1998, 34, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmood, D.; Holmes, D.; Bode, G. Frequency domain analysis of three-phase linear current regulators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2001, 37, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmood, D.; Holmes, G. Stationary frame current regulation of PWM inverters with zero steady-state error. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2003, 18, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Xue, B.; Zhou, M.; Fu, M.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Resonant Frequency Tracking Scheme for LLC Converter Based on Large and Small Signal Combined Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83390–83399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.; Lipo, T.; McGrath, B.; Kong, W. Optimized design of stationary frame three phase AC current regulators. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L.; Newman, M.; Zmood, D.; Holmes, D. A comparative analysis of multiloop voltage regulation strategies for single and three-phase UPS systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2005, 18, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Lu, D.; Agelidis, V. Current control of grid-connected boost inverter with zero steady-state error. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 2825–2834. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.; Thacker, T.; Fei, R.B.W.; Boroyevich, D. On zero steady-state error voltage control of single-phase PWM inverters with different load types. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 3285–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, H.; Watanabe, E.H.; Aredes, M. Instantaneous Power Theory and Applications to Power Conditioning; El-Hawari, M.E., Ed.; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoguang, Z.; Qingyao, H. Digital Feed-Forward Control Based on Motor Closed-Loop System Identification. In Proceedings of the 2010 Second International Conference on Computer Modeling and Simulation, Sanya, China, 22–24 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman, A. Proportional-resonant current controllers design based on desired transient performance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 5341–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkayam, M.; Kolesnik, S.; Basha, Y.; Kuperman, A. Loop shaping by single-resonant controllers for prescribed tracking of sinusoidal references. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 11352–11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, H.; Hatada, T. Voltage balancing control for a three-level diode-clamped converter in a medium-voltage transformer less hybrid active filter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbría, F.; Gordillo, F.; Gómez-Estern, F.; Salas, F.; Portillo, R.C.; Vázquez, S. Voltage balancing in three-level neutral-point-clamped converters via Luenberger observer. Control Eng. Pract. 2014, 25, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelovits, S.; Kadirkamanathan, Q.-C.Z.V.; Kuperman, A. UDE-based controller equipped with a multi-band-stop filter to improve the voltage quality of inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 7433–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Switching and sampling frequency, Ts−1 | 50 | kHz |

| Filter inductors, L1x | 340 | μH |

| AC side inductors, L2x | 9.43 | μH |

| Filter capacitors, Cx | 10 | μF |

| DC link capacitors, C1, C2 | 460 | μF |

| Fundamental frequency, f0 | 50 | Hz |

| Fundamental frequency, ω0 | 100π | rad/s |

| DC voltage, VDC | 800 | V |

| Damping factor, ζ | 0.001 | |

| Proportional gain, kC | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sassonker Elkayam, M.; Vinnikov, D. Enhanced Control Strategy for Three-Level T-Type Converters in Hybrid Power-to-X Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052409

Sassonker Elkayam M, Vinnikov D. Enhanced Control Strategy for Three-Level T-Type Converters in Hybrid Power-to-X Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(5):2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052409

Chicago/Turabian StyleSassonker Elkayam, Moria, and Dmitri Vinnikov. 2025. "Enhanced Control Strategy for Three-Level T-Type Converters in Hybrid Power-to-X Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 5: 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052409

APA StyleSassonker Elkayam, M., & Vinnikov, D. (2025). Enhanced Control Strategy for Three-Level T-Type Converters in Hybrid Power-to-X Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052409