Development, Experimental Assessment, and Application of a Vacuum-Driven Soft Bending Actuator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Development of a Vacuum-Powered Soft Bending Actuator Utilizing Thermoplastic Rubber Material

2.2. Design and Development of a Vacuum-Powered Soft Bending Actuator Utilizing Heat-Shrinkable Material

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

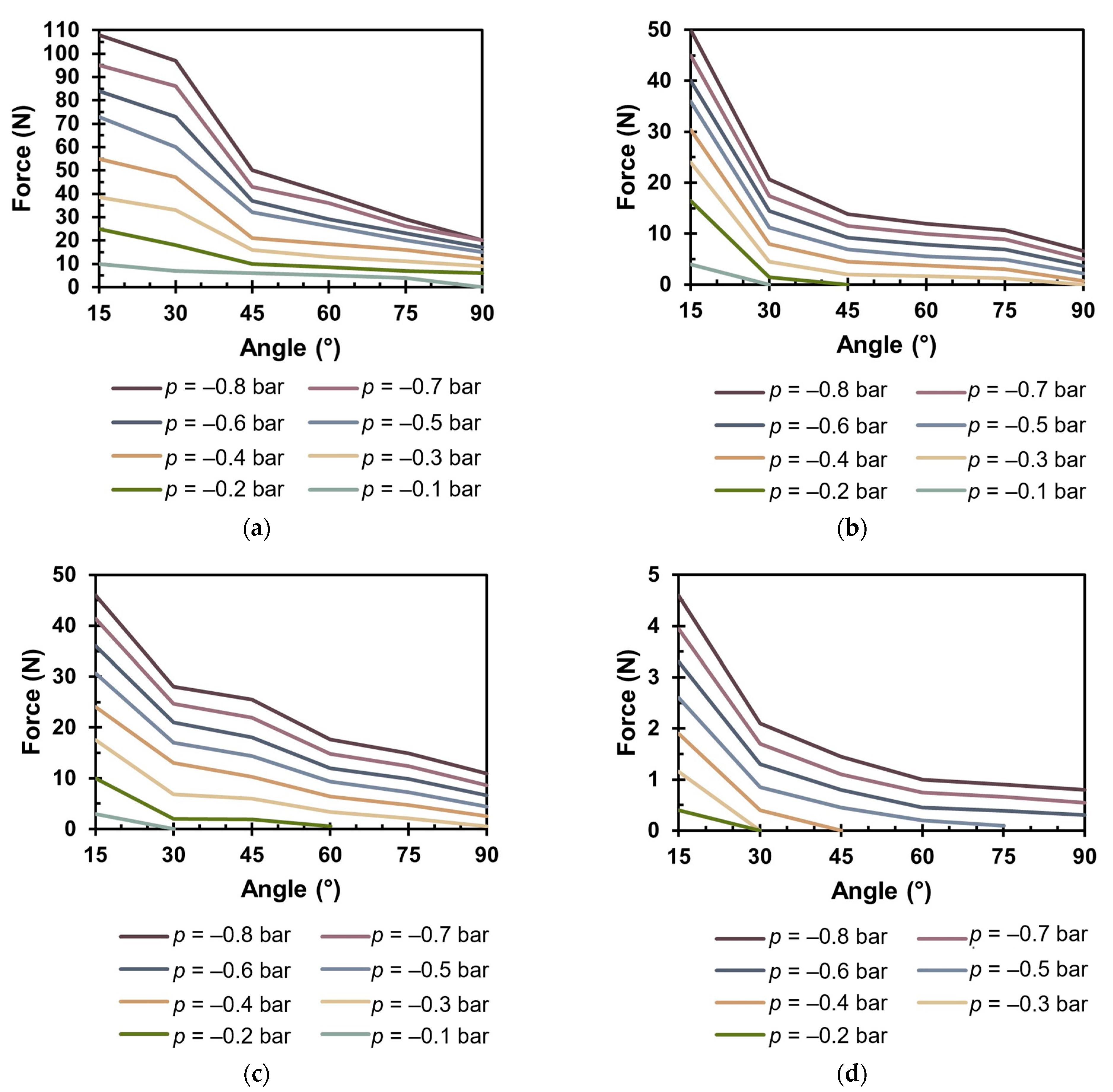

3.1. Experimental Assessment of a Maximum Blocking Force

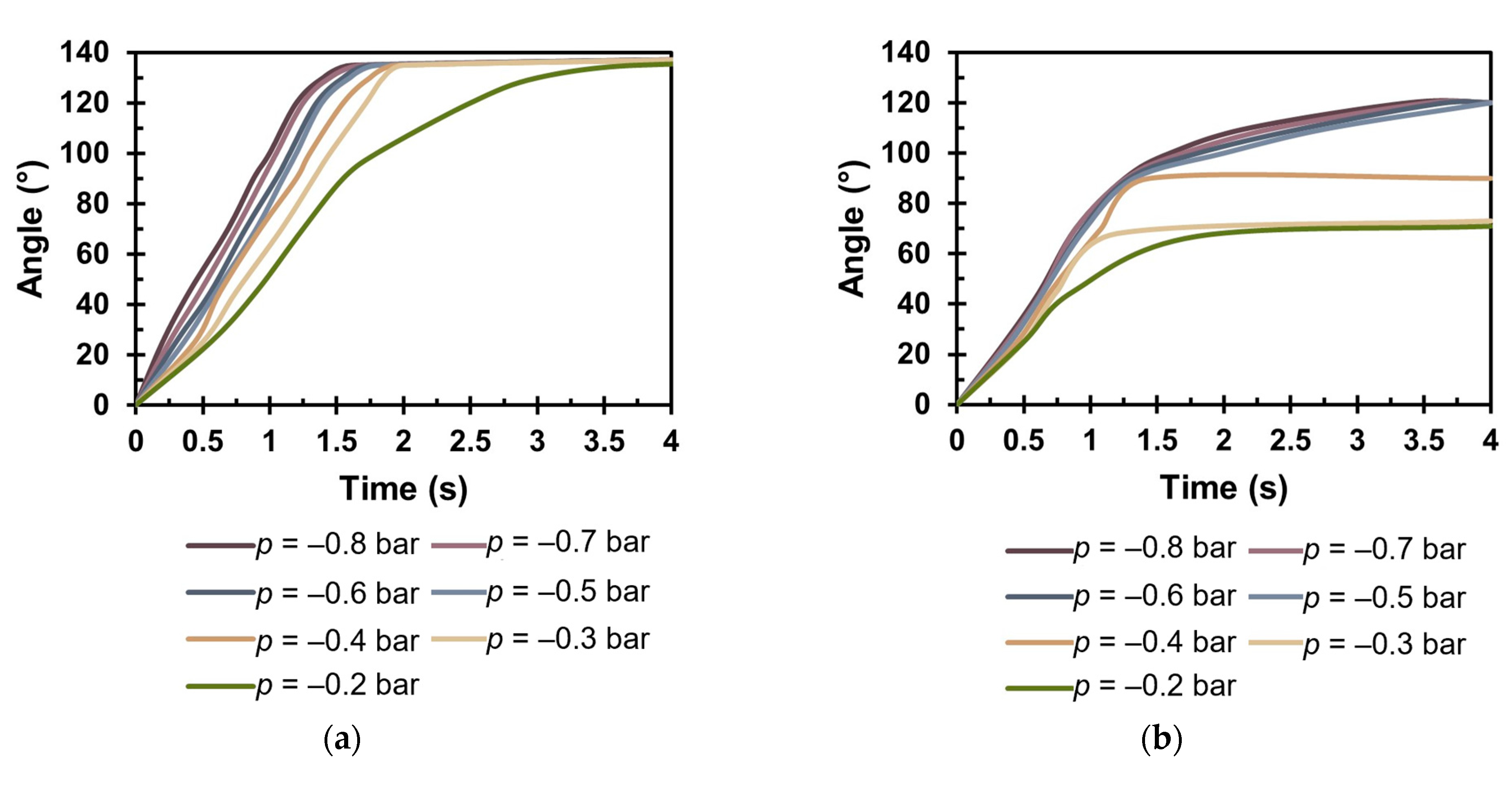

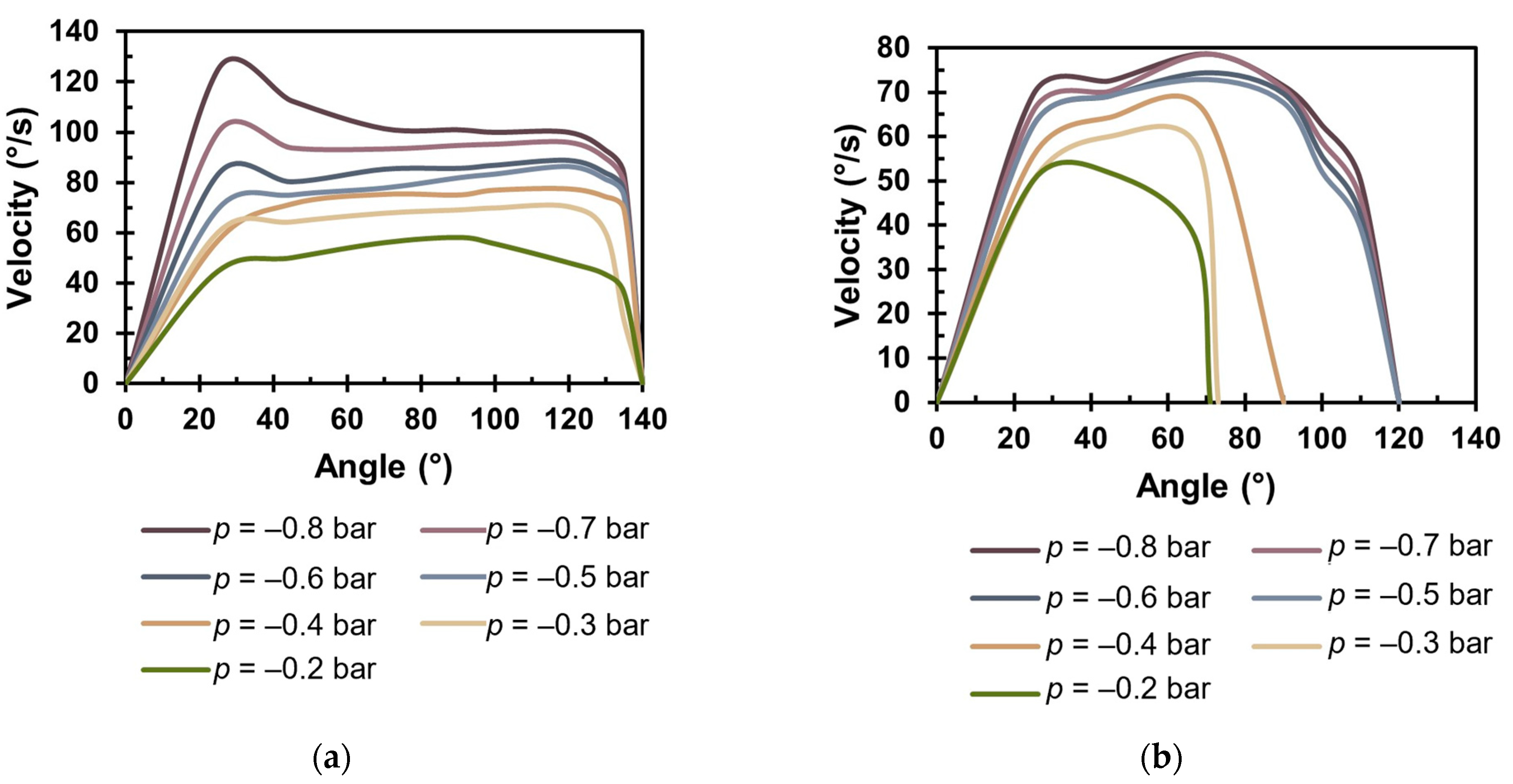

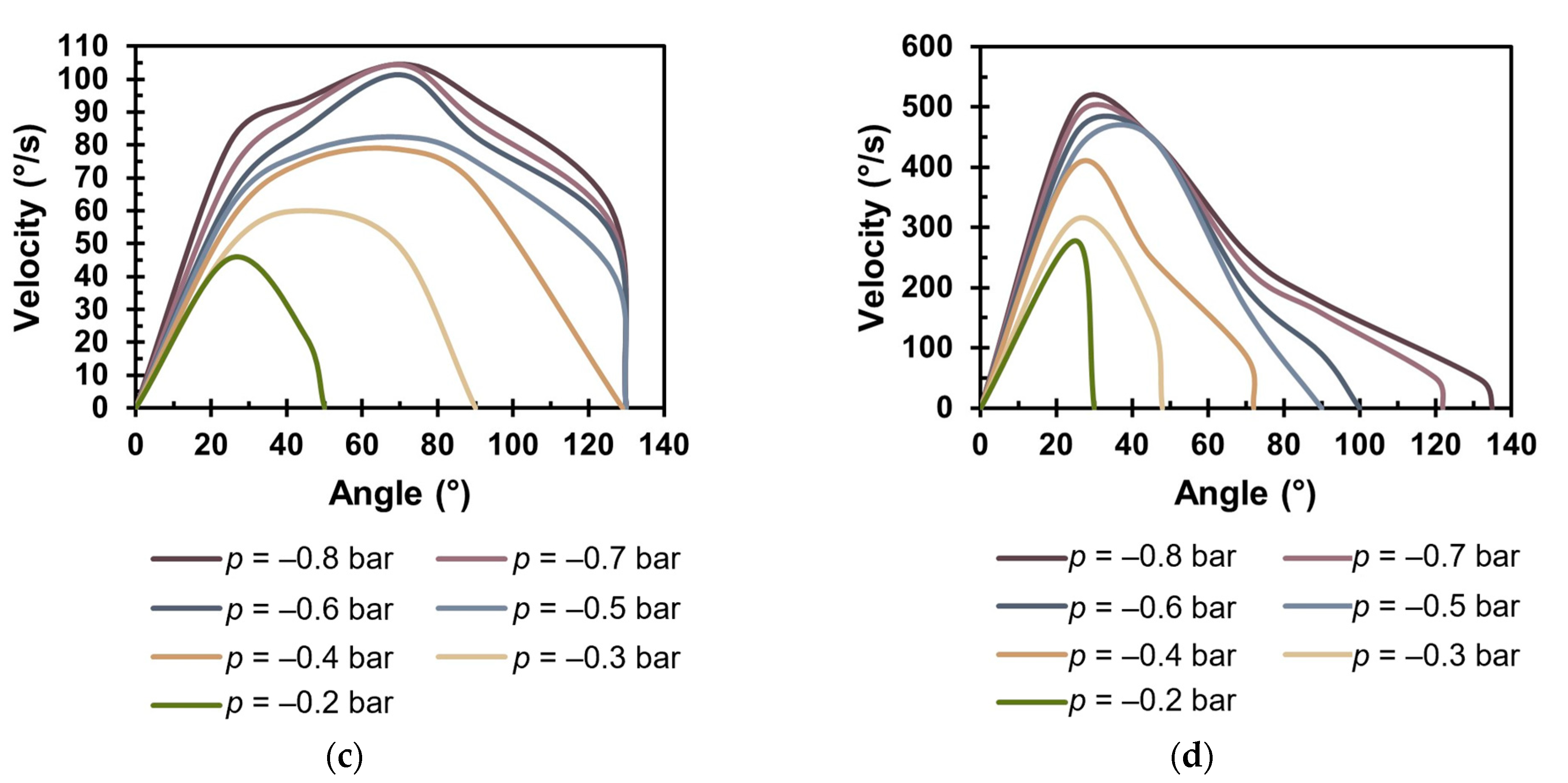

3.2. Experimental Assesment of Angular Velocity–Bending Angle Characteristic

4. Vacuum-Driven Soft Robotic Gripper Assembly

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoli, A.; Chapelle, F.; Corrales-Ramon, J.A.; Mezouar, Y.; Lapusta, Y. Review of soft fluidic actuators: Classification and materials modeling analysis. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021, 31, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Tawk, C.D.; Zolfagharian, A.; Pinskier, J.; Howard, D.; Young, T.; Lai, J.; Harrison, S.M.; Yong, Y.K.; Bodaghi, M.; et al. Soft pneumatic actuators: A review of design, fabrication, modeling, sensing, control and applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 59442–59485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawk, C.; Alici, G. A review of 3D-printable soft pneumatic actuators and sensors: Research challenges and opportunities. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Huang, J. Soft rehabilitation and nursing-care robots: A review and future outlook. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahillah, M.; Oh, N.; Rodrigue, H. A novel soft bending actuator using combined positive and negative pressures. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yao, J.; Zhou, P.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y. High-force soft pneumatic actuators based on novel casting method for robotic applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 306, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariya, N.; Kumar, P.; Singh, T. Experimental study on a bending type soft pneumatic actuator for minimizing the ballooning using chamber-reinforcement. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.; Rueben, J.; Volkenburg, T.V.; Hemleben, S.; Grimm, C.; Simonsen, J.; Mengüç, Y. Using an environmentally benign and degradable elastomer in soft robotics. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2017, 1, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, J.; Somwanshi, A.A.; Stancati, F.; Tyagi, G.; Patel, A.; Bhatt, N.; Rizzo, J.; Atashzar, S.F. What Happens When Pneu-Net Soft Robotic Actuators Get Fatigued? In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–21 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Vogt, D.M.; Rus, D.; Wood, R.J. Fluid-driven origami-inspired artificial muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13132–13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, W.; Robertson, M.A.; Paik, J. Modeling vacuum bellows soft pneumatic actuators with optimal mechanical performance. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Livorno, Italy, 24–28 April 2018; pp. 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Ying, C.; Xie, H.; Chen, J.; E, S. Origami-Inspired Vacuum-Actuated Foldable Actuator Enabled Biomimetic Worm-like Soft Crawling Robot. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, T.; Ohkura, S.; Azami, O.; Miyazaki, T.; Kawase, T.; Kawashima, K. Model of a coil-reinforced cylindrical soft actuator. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, Y.; Naniwa, K.; Nakanishi, D.; Osuka, K. Length control of a McKibben pneumatic actuator using a dynamic quantizer. Robomech J. 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mori, Y.; Hirai, S.; Kawamura, S.; Wang, Z. An empirical model of soft bellows actuator. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.; Rodrigue, H. Origami-based vacuum pneumatic artificial muscles with large contraction ratios. Soft Robot. 2019, 6, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, H.; Ma, T.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, P. A review of soft actuator motion: Actuation, design, manufacturing and applications. Actuators 2022, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Xie, R.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, X.; Huang, D.; Guan, Y.; Zhu, H. Pneumatic soft actuator with anisotropic soft and rigid restraints for pure in-plane bending motion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, D. Modeling and analysis of soft pneumatic network bending actuators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 26, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, R.; Sawada, Y. Design and grasping control of rib-reinforced bending soft actuators by vacuum driven. In Proceedings of the 2021 21st International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 12–15 October 2021; pp. 406–411. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Xie, C.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, K.; Wang, Z.; Hu, D.; Ding, R.; Jiao, Z. A new vacuum-powered soft bending actuator with programmable variable curvatures. Mater. Des. 2025, 250, 113641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himaruwan, S.; Tennakoon, C.L.; Kulasekera, A.L. Development and characterization of an origami-based vacuum-driven bending actuator for soft gripping. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Singapore, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori, H.; Hiyoshi, K.; Kimura, S.; Ishiguri, N.; Iwata, T. A self-deformation robot design incorporating bending-type pneumatic artificial muscles. Technologies 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Gong, W.; Feng, K.; Wang, X.; Xi, S. Design and motion analysis of soft robotic arm with pneumatic-network structure. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 095038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sut, D.J.; Sethuramalingam, P. Design optimisation and an experimental assessment of soft actuator for robotic grasping. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2024, 8, 758–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ge, Z.; Fan, P.; Zou, W.; Jiang, T.; Dong, L. Design and manufacture of a flexible pneumatic soft gripper. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Hu, D.; Chen, W.; Yang, G.; Han, X. Design, characterization and optimization of multi-directional bending pneumatic artificial muscles. J. Bionic Eng. 2021, 18, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Hao, W.; Xiao, F.; Chen, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Soft pneumatic actuator from particle reinforced silicone rubber: Simulation and experiments. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tong, L. Optimal design and experimental validation of 3D printed soft pneumatic actuators. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 115010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torzini, L.; Puggelli, L.; Volpe, Y.; Governi, L.; Buonamici, F. Characterization of fatigue behavior of 3D printed pneumatic fluidic elastomer actuators. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregov, G.; Ploh, T.; Kamenar, E. Design, development and experimental assessment of a cost-effective bellow pneumatic actuator. Actuators 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.; Ogawa, A.; Nakamoto, H.; Sonoura, T.; Eto, H. Suction pad unit using a bellows pneumatic actuator as a support mechanism for an end effector of depalletizing robots. ROBOMECH J. 2020, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, A.; Bone, G.M. Origami-inspired soft pneumatic actuators: Generalization and design optimization. Actuators 2023, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregov, G.; Pincin, S.; Šoljić, A.; Kamenar, E. Position Control of a Cost-Effective Bellow Pneumatic Actuator Using an LQR Approach. Actuators 2023, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Pressure | p (Bar) | θ (°) | F (N) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPE | Positive | 3 | 340 | - | [31] |

| Ecoflex-30 | Positive | 0.6 | 150 | 1 | [19] |

| Dragon skin 30 | Positive | 0.6 | 151 | 1.2 | [20] |

| Dragon skin 20 | Negative | −0.89 | - | 2.9 | [21] |

| Silicon rubber | Negative | −0.8 | 171.5 | - | [22] |

| PVC/TPU | Negative | −0.6 | 84 | 1.8 | [23] |

| PLA | Posit. and Negat. | 0.6 and −0.6 | 34.7 | 150 | [6] |

| VSBA-1 | VSBA-2 | VSBA-3 | VSBA-4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p (bar) | 0 (kg) | 0.5 (kg) | 0 (kg) | 0.5 (kg) | 0 (kg) | 0.5 (kg) | 0 (kg) | 0.1 (kg) |

| −0.8 | 140 | 135 | 120 | 90 | 130 | 110 | 135 | 90 |

| −0.7 | 140 | 135 | 120 | 90 | 130 | 90 | 120 | 70 |

| −0.6 | 140 | 135 | 120 | 75 | 130 | 70 | 100 | 60 |

| −0.5 | 140 | 135 | 120 | 45 | 130 | 70 | 90 | 45 |

| −0.4 | 140 | 115 | 90 | 45 | 110 | 44 | 50 | 45 |

| −0.3 | 140 | 80 | 73 | 24 | 90 | 24 | 45 | 25 |

| −0.2 | 140 | 40 | 71 | 24 | 50 | 24 | 24 | 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gregov, G.; Vuković, T.; Gašparić, L.; Pongrac, M. Development, Experimental Assessment, and Application of a Vacuum-Driven Soft Bending Actuator. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052557

Gregov G, Vuković T, Gašparić L, Pongrac M. Development, Experimental Assessment, and Application of a Vacuum-Driven Soft Bending Actuator. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(5):2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052557

Chicago/Turabian StyleGregov, Goran, Tonia Vuković, Leonardo Gašparić, and Matija Pongrac. 2025. "Development, Experimental Assessment, and Application of a Vacuum-Driven Soft Bending Actuator" Applied Sciences 15, no. 5: 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052557

APA StyleGregov, G., Vuković, T., Gašparić, L., & Pongrac, M. (2025). Development, Experimental Assessment, and Application of a Vacuum-Driven Soft Bending Actuator. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15052557