Design of a Stability Augmentation System for an Unmanned Helicopter Based on Adaptive Control Techniques

Abstract

:1. Introduction

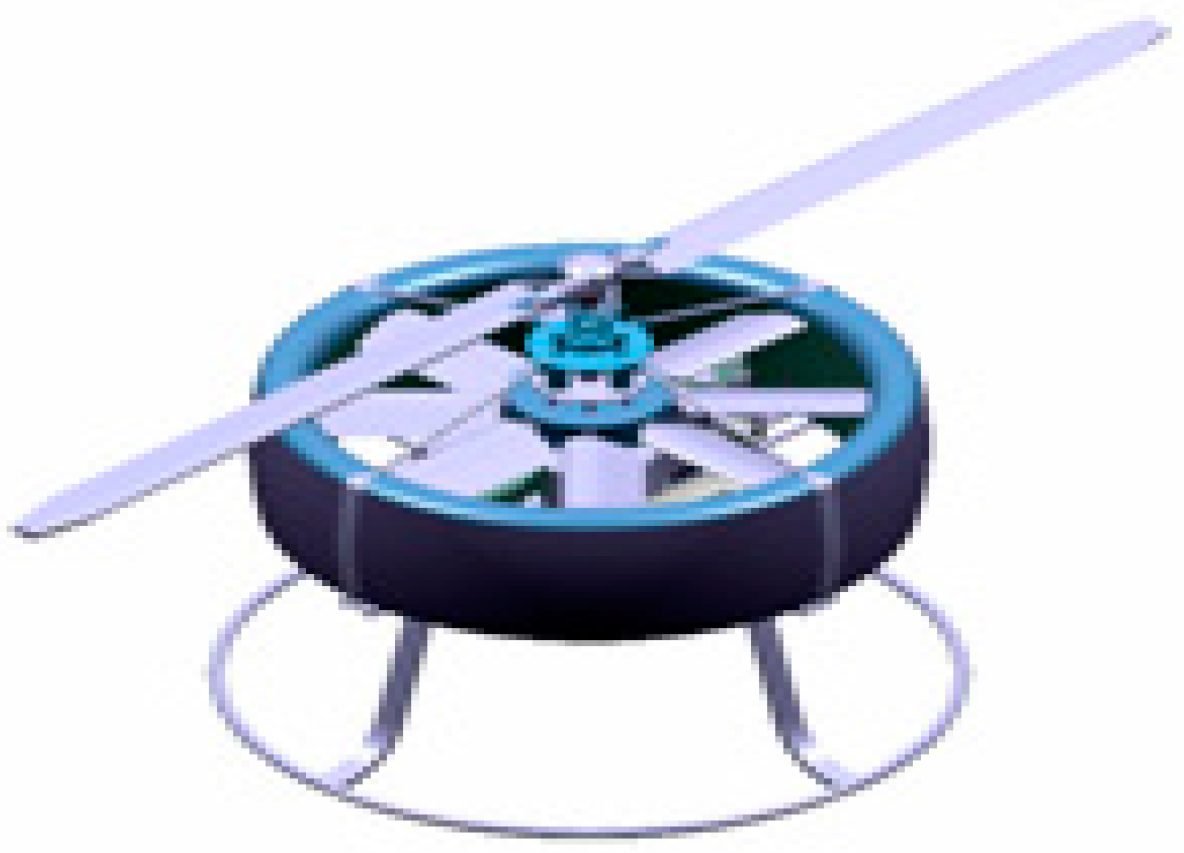

2. The Control Problem for the Prototype UH Stability Augmentation System

3. Design of the Stability Augmentation System Based on an Adaptive Model Feedback Control Algorithm

3.1. Theorem 1

3.2. Proof

3.3. Remarks

4. The Improvement and Application of the Adaptive Laws

5. Flight Tests

- (1)

- The model parameters: and ;

- (2)

- The initial values of adjustable parameters: and are assumed to equal zero, and ;

- (3)

- The time constant of the filter: ;

- (4)

- The parameters of the adaptive control laws: ; ; .

5.1. Task 1: Numerical Simulation

5.2. Task 2: Flight Tests

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, G.; Chen, B.M.; Lee, T.H. Unmanned Rotorcraft Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; Ge, S.S.; Chen, C.; Fua, C.H.; Lee, T.H. Modeling, Control and Coordination of Helicopter Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.V. Flight Dynamics Principles: A Linear Systems Approach to Aircraft Stability and Control, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler, B. Identification Modeling and Characteristics of Miniature Rotorcraft, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, D.H.; Kim, H.J.; Sastry, S. Control System Design for Rotorcraft-Based Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Time-Domain System Identification. In Control Applications, Proceedings of the 2000 IEEE International Conference on, Anchorage, AK, USA, 25–27 September 2000; pp. 808–813.

- Takahashi, M.; Schulein, G.; Whalley, M. Flight Control Law Design and Development for an Autonomous Rotorcraft. In Proceedings of the 64th Annual Forum of the American Helicopter Society, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 29 April–1 May 2008; pp. 1652–1671.

- How, J.; Bethke, B.; Frank, A.; Dale, D.; Vian, J. Real time indoor autonomous vehicle test environment. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2008, 28, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.H.; Kim, H.J.; Sastry, S. Decentralized Nonlinear Model Predictive Control of Multiple Flying Robots. In Decision and Control, Proceedings of 42nd IEEE Conference on, Maui, HI, USA, December 2003; pp. 3621–3626.

- Buskey, G.; Wyeth, G.; Roberts, J. Autonomous Helicopter Hover Using an Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seoul, Korea, 21–26 May 2001; pp. 1635–1640.

- Garcia, R.; Valavanis, K. The implementation of an autonomous helicopter testbed. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2009, 54, 423–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerlas, A.J.; Walker, D.J.; Postlethwaite, I.; Strange, M.E.; Howitt, J.; Gubbels, A.W. Evaluating H∞ controllers on the NRC Bell 205 fly-by-wire helicopter. Control Eng. Pract. 2001, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.J. Multivariable control of the longitudinal and lateral dynamics of a fly-by-wire helicopter. Control Eng. Pract. 2003, 11, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadewadikar, J.; Lewis, F.; Subbarao, K.; Chen, B.M. Structured H-infinity command and control-loop design for unmanned helicopters. J. Guid. Control Dynam. 2008, 31, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dytek, Z.T. Adaptive Control of Unmanned Aerial Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krupadanam, A.S.; Annaswamy, A.M.; Mangoubi, R.S. Multivariable adaptive control design with applications to autonomous helicopters. J. Guid. Control Dynam. 2002, 25, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, G. Modeling and model reference adaptive control of aircraft with asymmetric damage. J. Guid. Control Dynam. 2010, 33, 1500–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, J.C.; Faulwasser, T.; Lorenz, S.; Findeisen, R. Optimization-Based Feed Forward Path Following for Model Reference Adaptive Control of an Unmanned Helicopter. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 19–22 August 2013.

- Rusnak, I.; Weiss, H.; Barkana, I. Improving the performance of existing missile autopilot using simple adaptive control. Int. J. Adapt Control Signal Process. 2014, 28, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neild, S.A.; Yang, L.; Wagg, D.J. A modified model reference adaptive control approach for systems with noise or unmodelled dynamics. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part I: J. Syst. Control Eng. 2008, 222, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanZwieten, T.; Gilligan, E.; Wall, J.; Orr, J.; Miller, C.; Hanson, C. Adaptive Augmenting Control Flight Characterization Experiment on an F/A-18. In Proceedings of American Astronautical Society Guidance & Control Conference, Breckenridge, CO, USA, 31 January–5 February 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–17.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheng, S.; Sun, C. Design of a Stability Augmentation System for an Unmanned Helicopter Based on Adaptive Control Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2015, 5, 575-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/app5030575

Sheng S, Sun C. Design of a Stability Augmentation System for an Unmanned Helicopter Based on Adaptive Control Techniques. Applied Sciences. 2015; 5(3):575-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/app5030575

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheng, Shouzhao, and Chenwu Sun. 2015. "Design of a Stability Augmentation System for an Unmanned Helicopter Based on Adaptive Control Techniques" Applied Sciences 5, no. 3: 575-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/app5030575

APA StyleSheng, S., & Sun, C. (2015). Design of a Stability Augmentation System for an Unmanned Helicopter Based on Adaptive Control Techniques. Applied Sciences, 5(3), 575-586. https://doi.org/10.3390/app5030575