Modal-Energy-Based Neuro-Controller for Seismic Response Reduction of a Nonlinear Building Structure

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Motion Equation of a Nonlinear Building System

3. Modal-Energy-Based Neuro-Controller

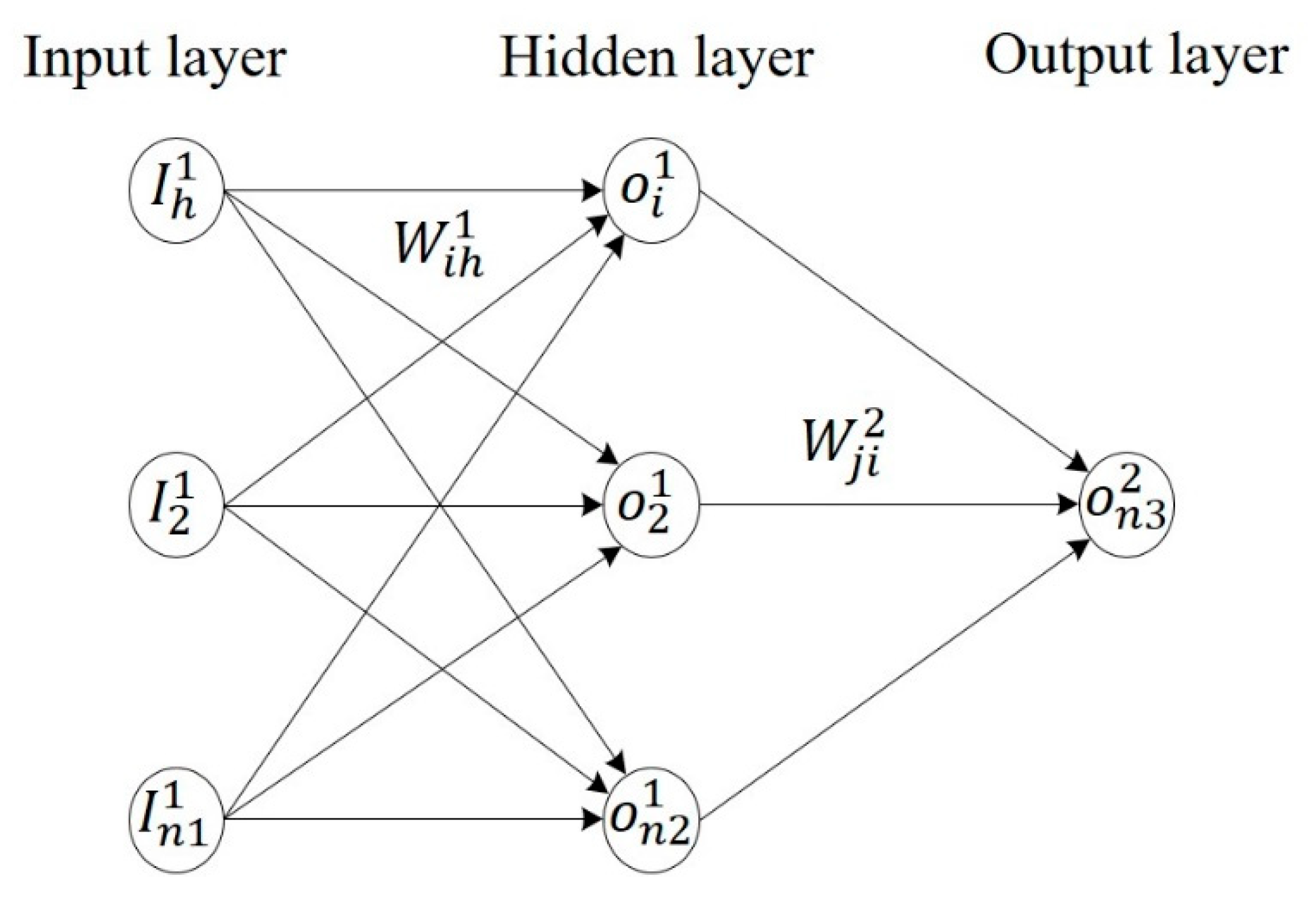

3.1. Multilayer Perceptron

3.2. Modal Energy and the Objective Function

3.3. Control Algorithm and Training Rule

4. Numerical Analysis

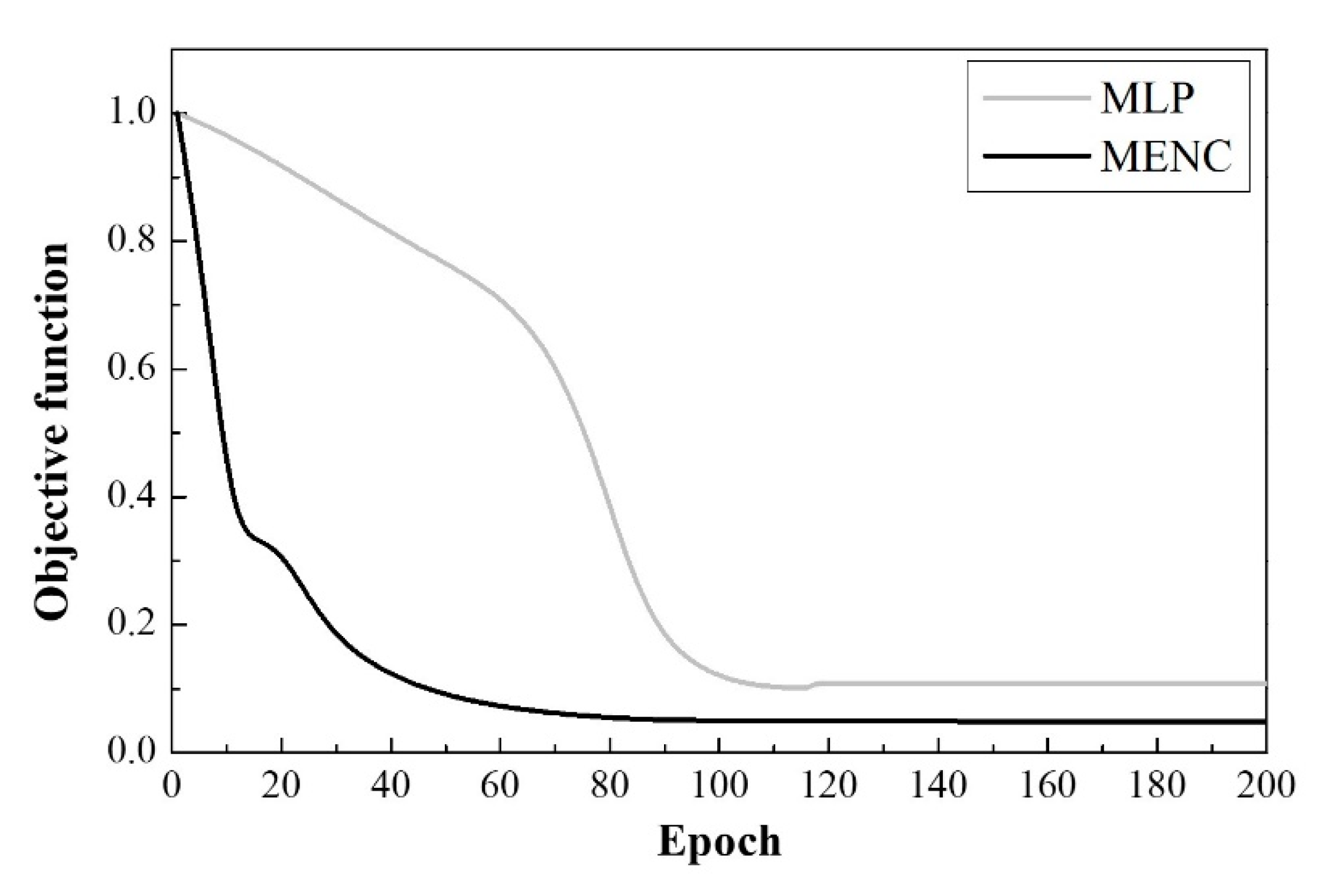

4.1. Training the Neuro-Controller

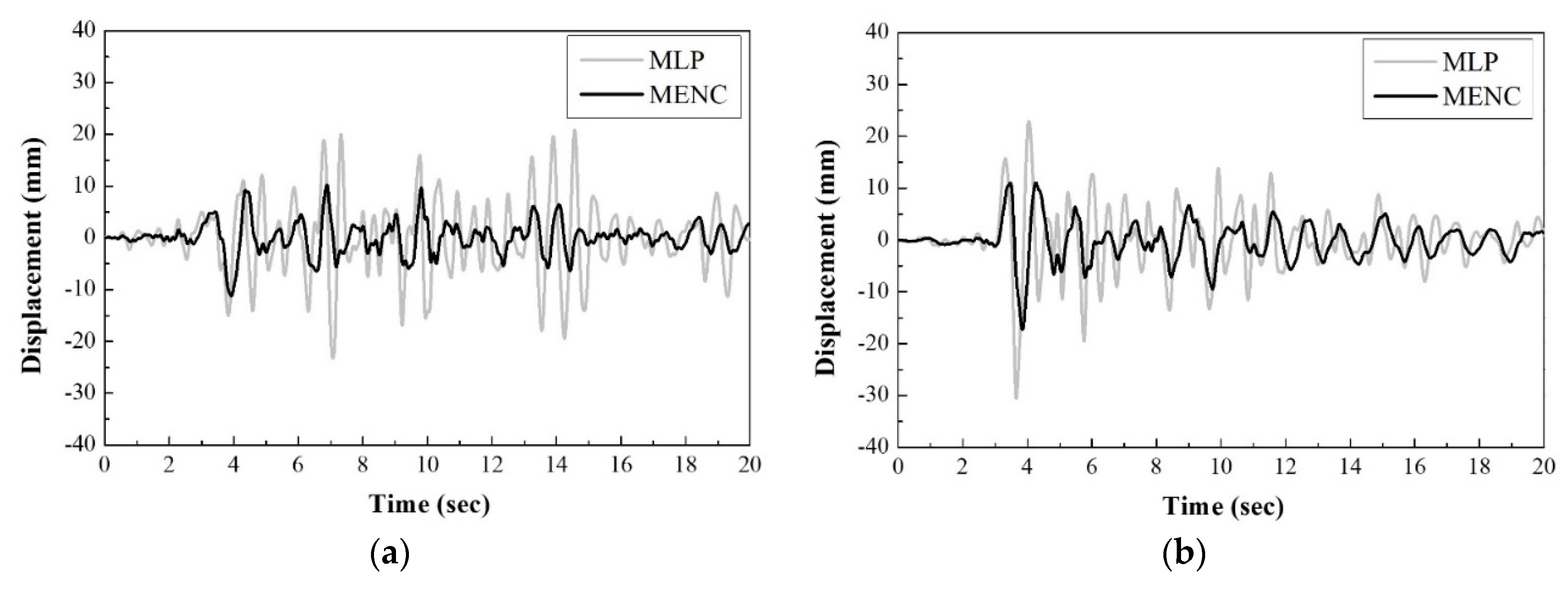

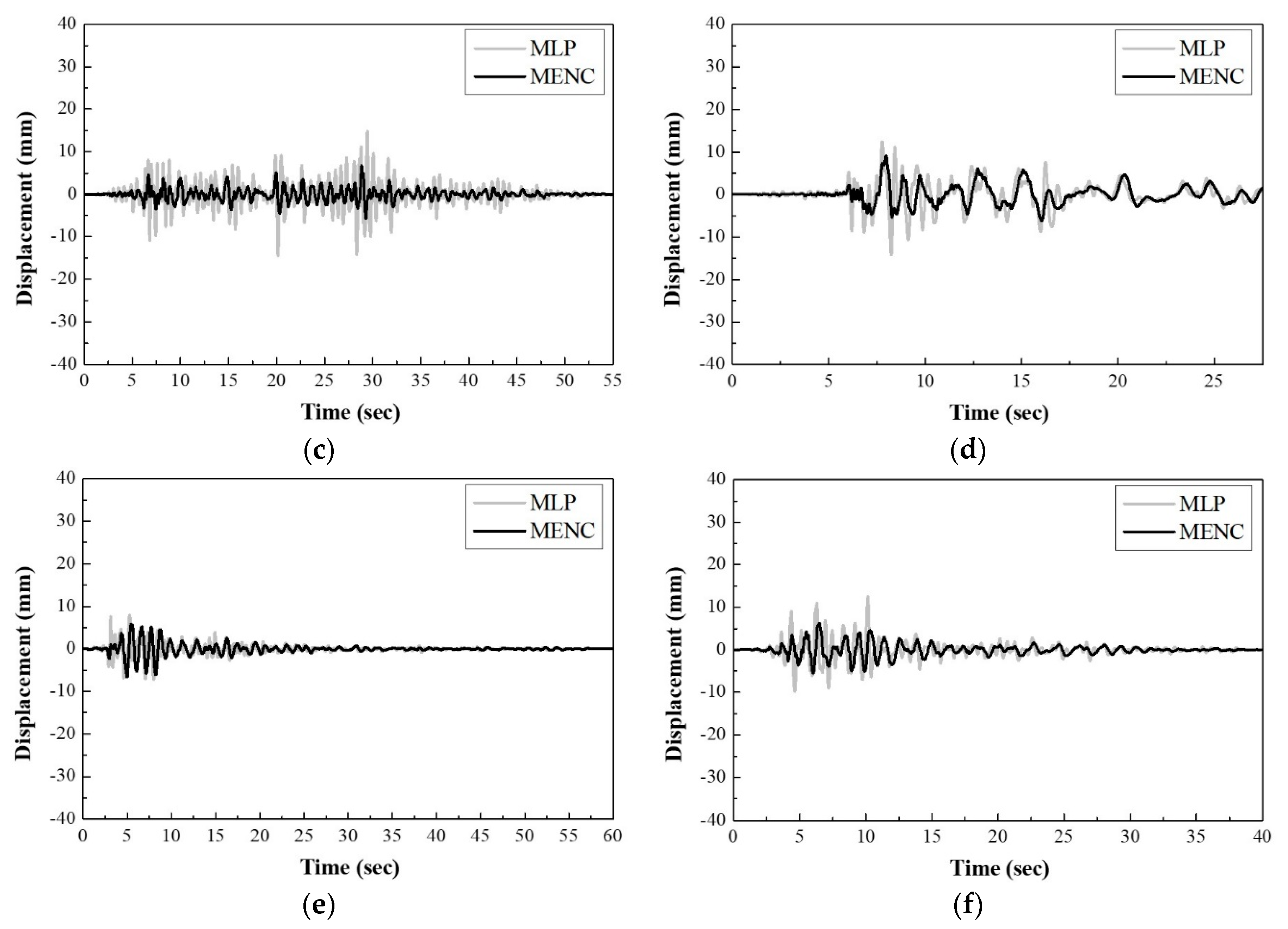

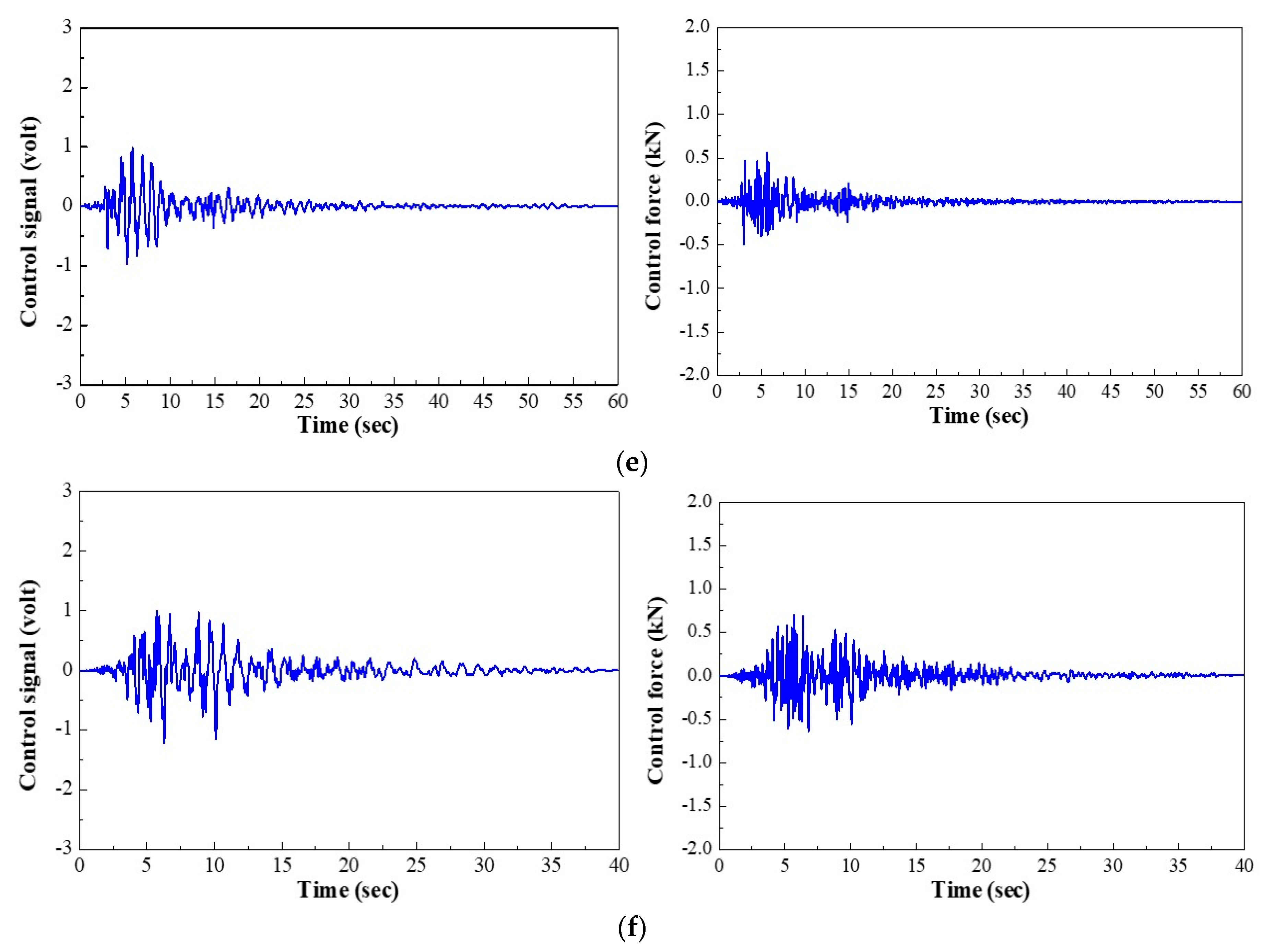

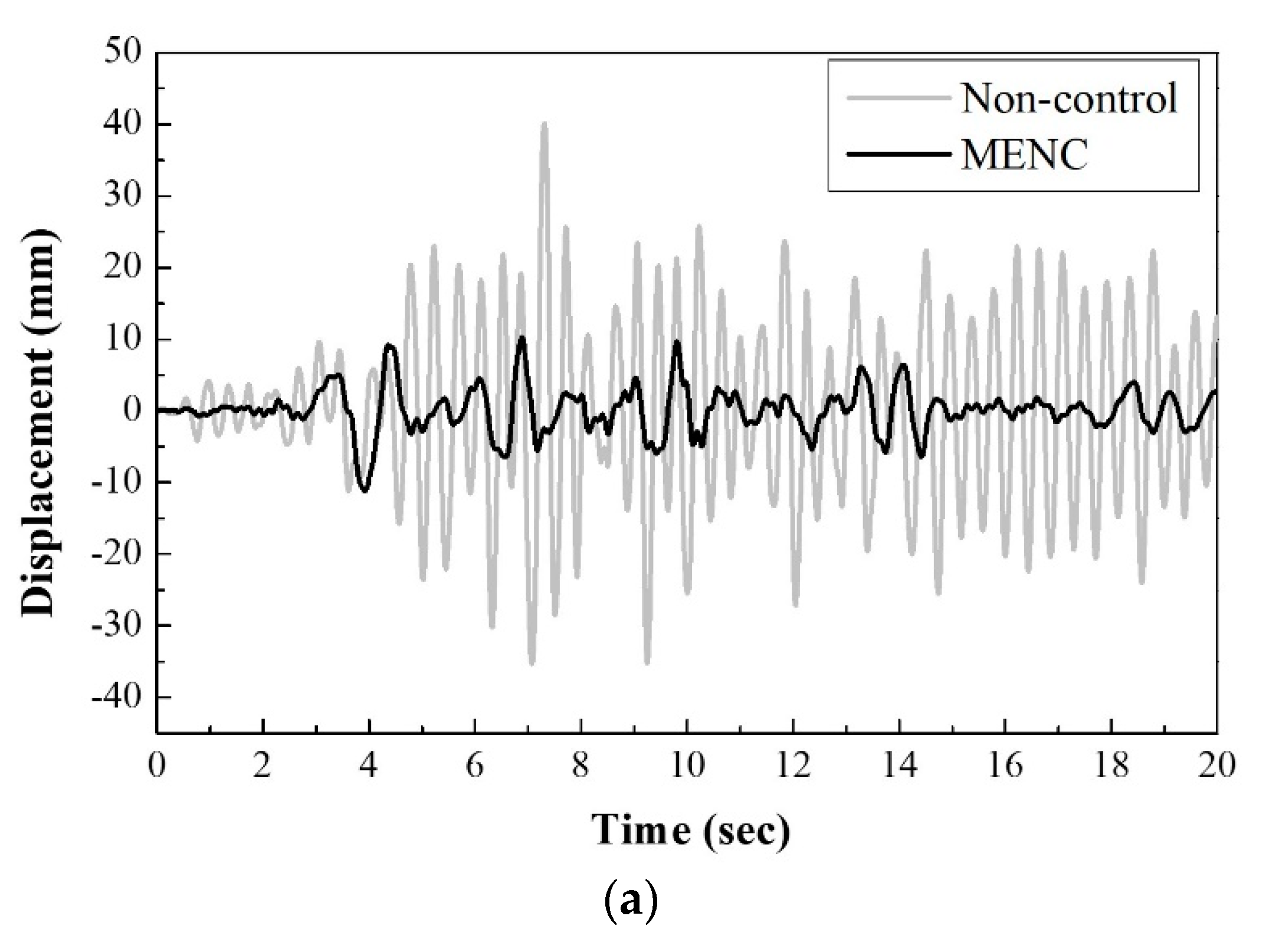

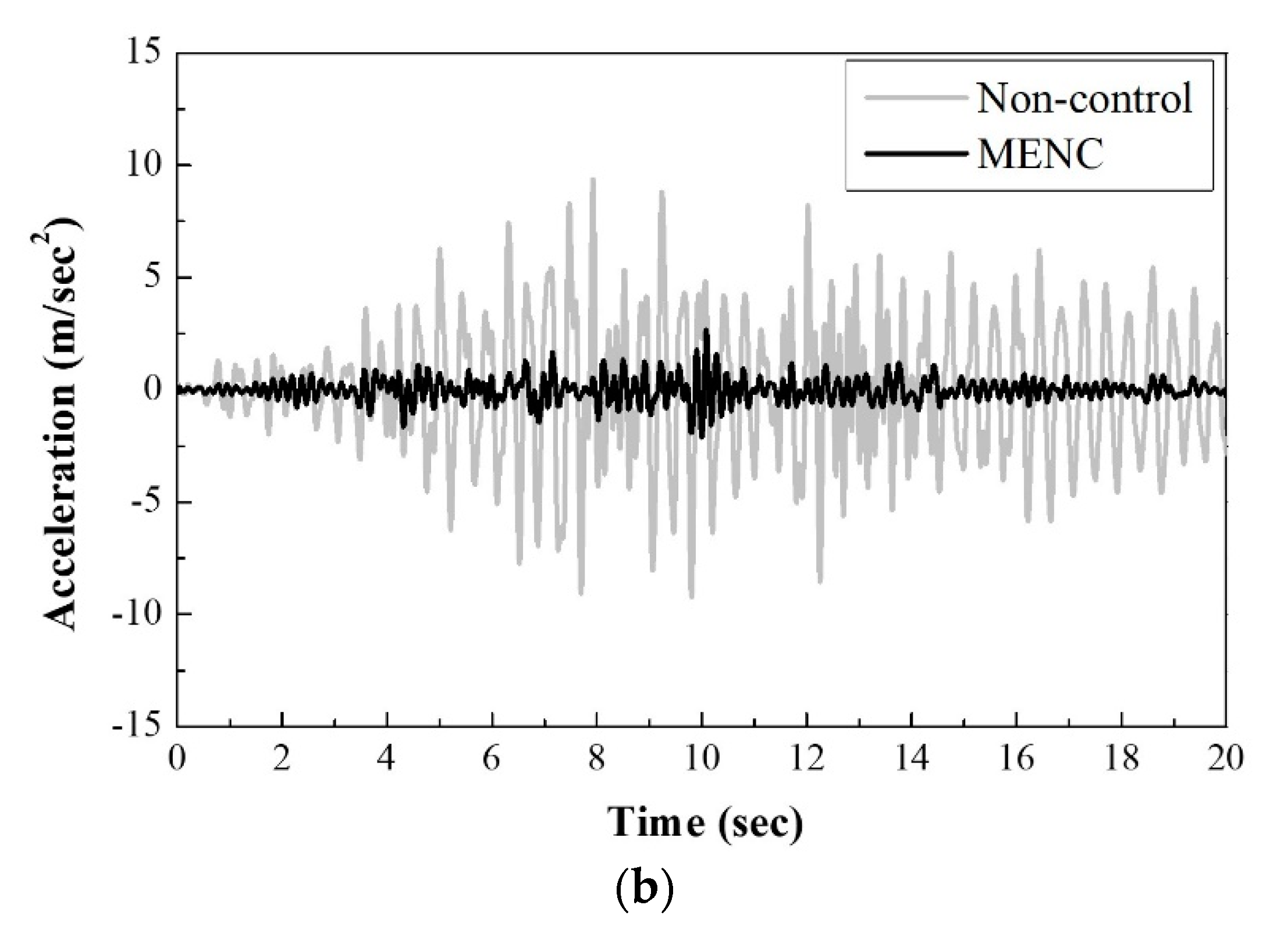

4.2. Comparison of Control Results

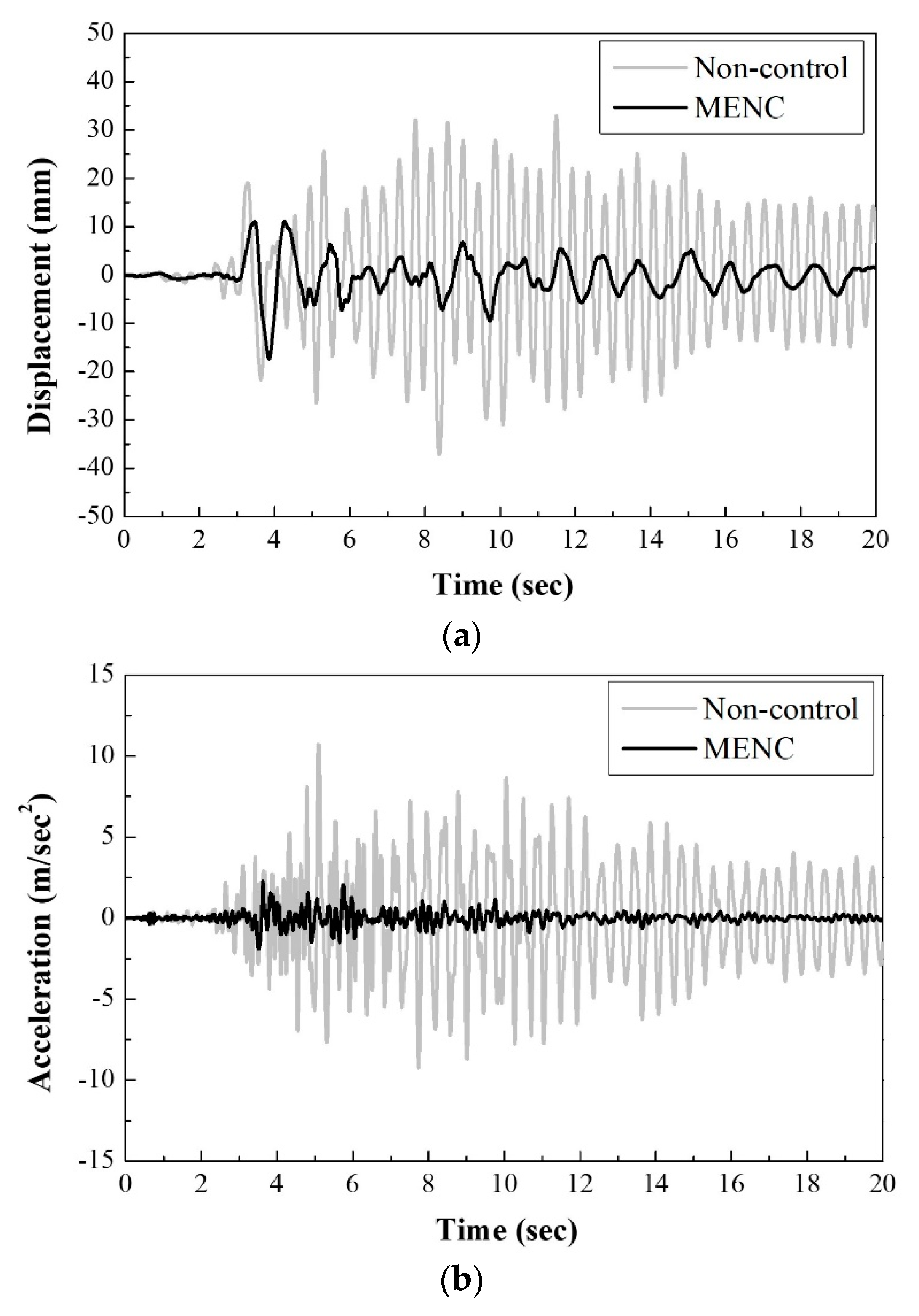

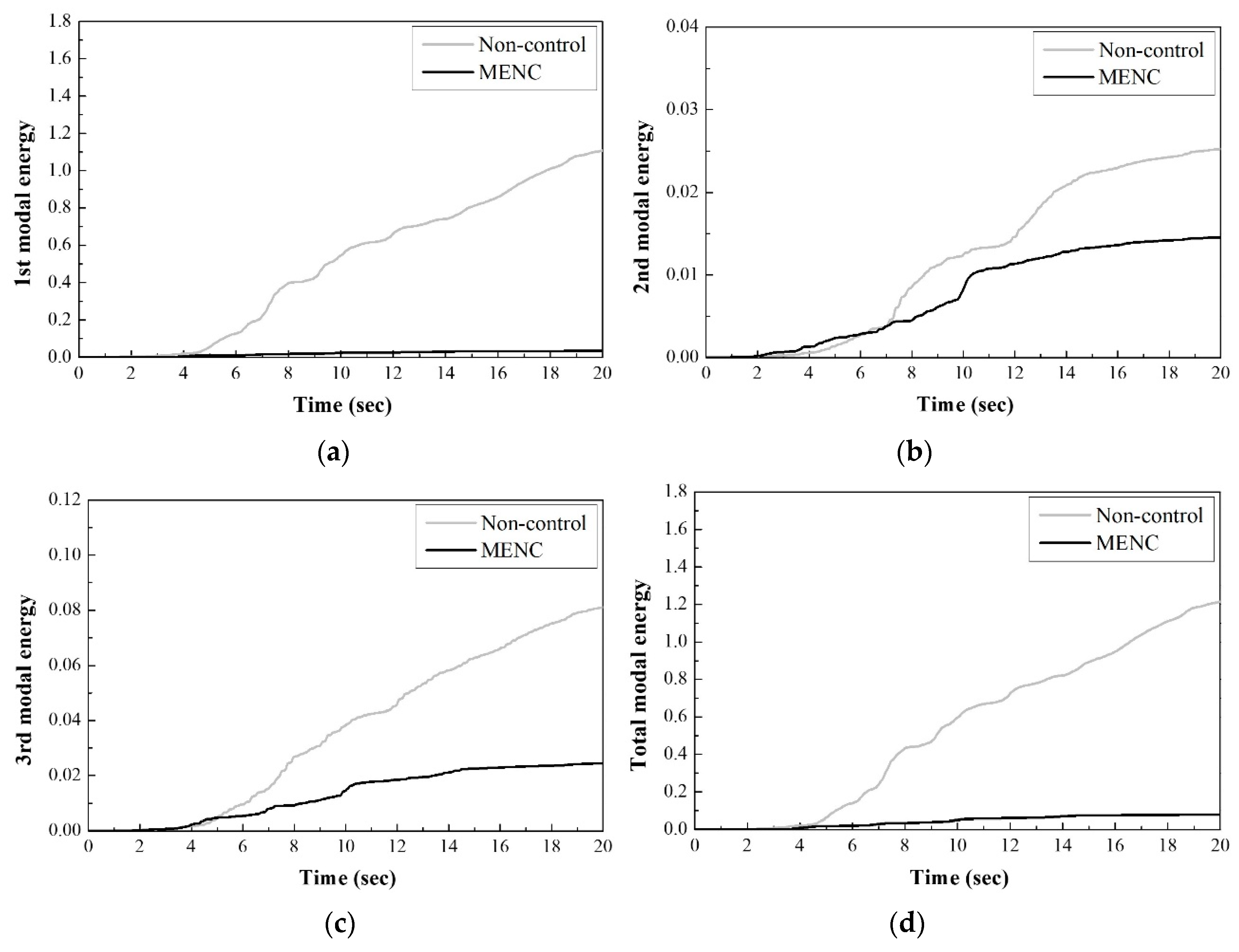

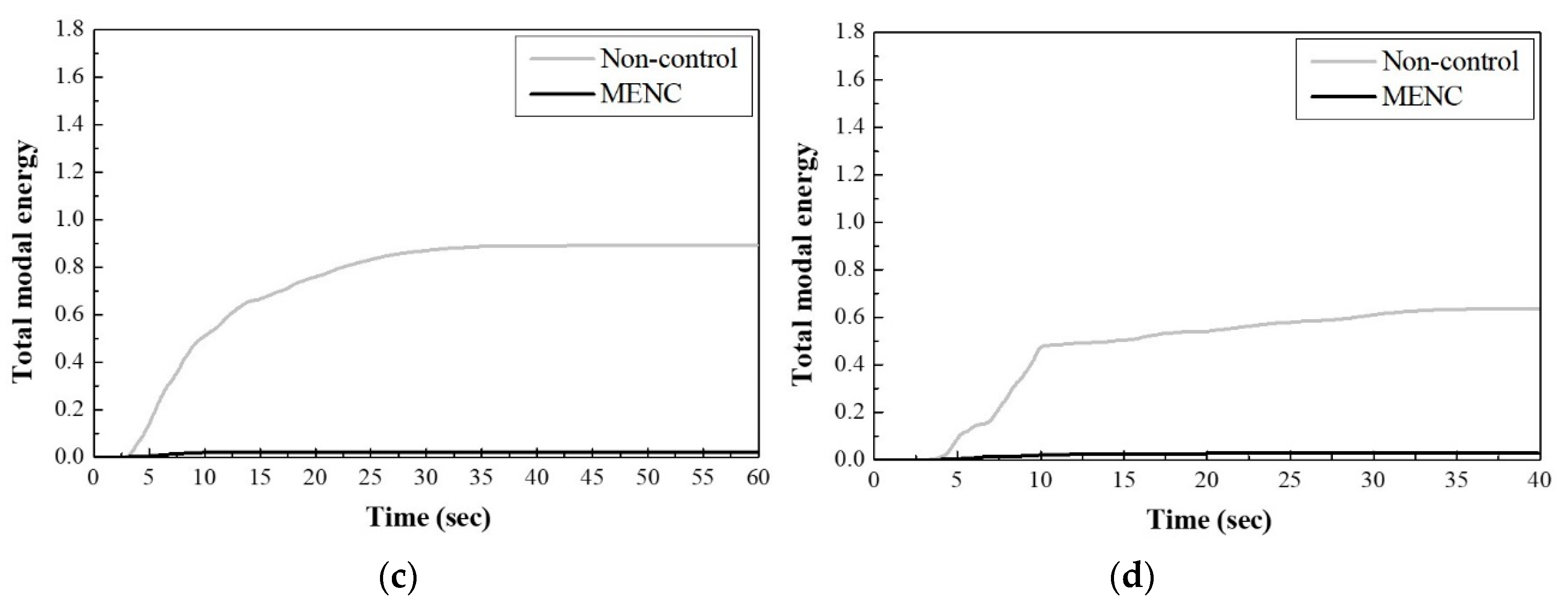

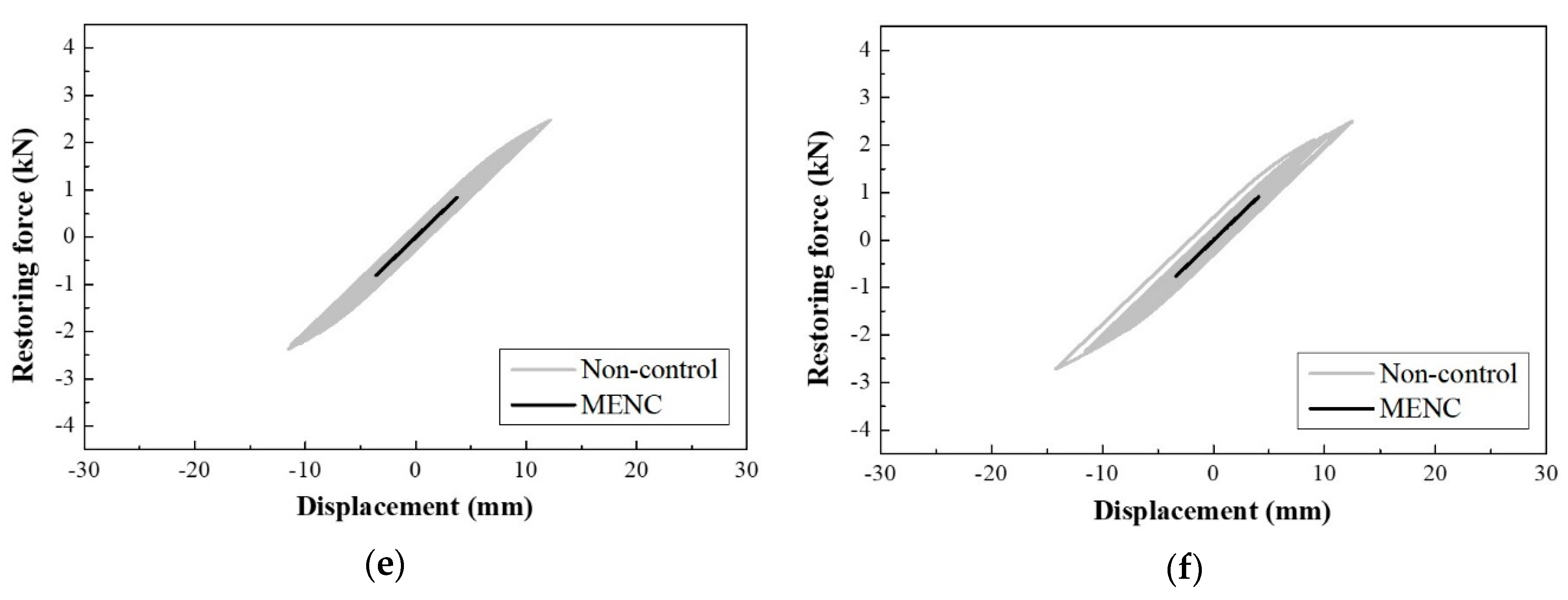

4.3. Numerical Analysis of Nonlinear Building Structures

5. Conclusions

- The proposed MENC algorithm was faster compared to the MLP algorithm in the training process to control the seismic load of an active mass damper.

- The proposed MENC algorithm is able to effectively reduce the structural responses under unknown earthquakes than conventional MLP.

- The proposed MENC algorithm was able to significantly reduce the structural response under all used seismic loads when applied to an AMD system.

- The structural responses and modal energy were suppressed effectively by the MENC algorithm. In addition, the first modal energy affected the whole structure’s energy because the first mode is dominant in this structure’s case.

- From the restoring force results, the non-controlled structural responses exhibited nonlinear hysteretic behaviors. This nonlinear behavior almost disappeared after control by the proposed MENC algorithm. Therefore, when the structure is in the nonlinear state, the proposed MENC algorithm can effectively reduce the seismic response by the control signal in real time depending on the structural responses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.M.; Tsai, K.H.; Qi, G.Z.; Yang, C.S.; Amini, F. Neural network for structure control. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 1995, 9, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaboussi, J.; Joghataie, A. Active control of structure using neural networks. J. Eng. Mech. ASCE 1995, 121, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Hani, K.; Ghaboussi, J. Nonlinear structural control using neural networks. J. Eng. Mech. ASCE 1998, 124, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Hani, K.; Ghaboussi, J. Neural networks for structural control of a benchmark problem, active tendon system. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 1998, 27, 1225–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liut, D.A.; Matheu, E.E.; Singh, M.P.; Mook, D.T. Neural-network control of building structures by a force-matching training scheme. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 1999, 28, 1601–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, I.W. Neuro-control of seismically excited steel structure through sensitivity evaluation scheme. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 2001, 30, 1361–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.C.; Fadali, M.S.; Saiidi, M.S.; Lee, K.S. Neural network active control of structures with earthquake excitation. Int. J. Control Autom. 2005, 3, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Madan, A. Vibration control of building structures using self-organizing and self-learning neural networks. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 287, 759–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. Neural Network-Based Structural Vibration Control System. Ph.D. Thesis, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A.D. The Maximum Principle of Pontryagin in Control and in Optimal Control; Queen’s University: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubczyk, B.; Sontag, E. Controllability of nonlinear discrete-time systems: A lie-algebraic approach. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1990, 28, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanov, M.J.; Sharifov, Y.A. Pontryagin’s maximum principle for the optimal control problems with multipoint boundary conditions. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2015, 2015, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greydanus, S.; Dzamba, M.; Yosinski, J. Hamiltonian neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01563. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.D.; Dey, B.; Chakraborty, A. Symplectic ODE-Net: Learning Hamiltonian dynamics with control. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.12077. [Google Scholar]

- Zizouni, K.; Fali, L.; Sadek, Y.; Bousserhane, I.K. Neural network control for earthquake structural vibration reduction using MRD. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 9, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Pozo, F.; Bahar, A. Force-derivative feedback semi-active control of base-isolated buildings using large-scale MR fluid dampers. Struct. Control Health 2012, 19, 120–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.; Dumne, S.; Shrimali, M. Earthquake response of asymmetric building with MR damper. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2014, 13, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattulli, V.; Lepidi, M.; Potenza, F. Seismic protection of frame structures via semi-active control: Modeling and implementation issues. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2009, 8, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Botto, M.A.; Morais, P.; Suleman, A. Semi-active structural vibration control of base-isolated buildings using magnetorheological dampers. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2017, 37, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Duan, C. Experimental investigation on semi-active control of base isolation system using magnetorheological dampers for concrete frame structure. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, D.; Nikitas, N. A novel hybrid semi-active mass damper configuration for structural applications. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, J. Active vibration control of rib stiffened plate by using decentralized velocity feedback controllers with inertial actuators. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Semi-Active Structural Motion Control by Transfer of Modal Energy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Emad, N.A. Acceleration Behavior of Semi-Active Structural Motion Control by Transfer of Modal Energy. Master’s Thesis, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benavent-Climent, A.; Morillas, L.; Escolano-Margarit, D. Seismic performance and damage evaluation of a reinforced concrete frame with hysteretic dampers through shake-table tests. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 2014, 43, 2399–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enrıquez-Zarate, J.; Abundis-Fong, H.F.; Velazquez, R.; Gutierrez, S. Passive vibration control in a civil structure: Experimental results. Meas. Control 2019, 52, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, T.T.; Wen, Y.K. Random vibration of hysteretic degrading systems. J. Eng. Mech. Div. ASCE 1981, 107, 1069–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Geoffrey, E.H.; Williams, R.J. Learning Internal Representations by Error Propagation; ICS Report; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center. Available online: https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu/site (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Tu, J.; Lin, X.; Tu, B.; Xu, J.; Tan, D. Simulation and experimental tests on active mass damper control system based on model reference adaptive control algorithm. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 4826–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q. Seismic performance assessment of electric power systems subjected to spatially correlated earthquake excitations. Struct. Infrastruct. E 2019, 15, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plodpradit, P.; Dinh, V.N.; Kim, K.D. Coupled Analysis of Offshore Wind Turbine Jacket Structures with Pile-Soil-Structure Interaction Using FAST v8 and X-SEA. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Quantity | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mass of each floor | 200 kg | |

| Mass of AMD | 18 kg | |

| Stiffness coefficient of each floor | 2.25 × 105 N/m | |

| Damping ratio of first mode | 0.6% | |

| Damping ratio of second mode | 0.7% | |

| Damping ratio of third mode | 0.3% | |

| Valve gain | 321.4 × 102 m3/s | |

| Valve gain | 0.28 × 10−6 m3/s | |

| Time constant | 0.1 | |

| Piston effective area | 1.52 × 10−3 m2 | |

| Volume of the cylinder | 4.56 × 10−4 m3 | |

| Leakage coefficient | 1.0 × 10−11 | |

| Compressibility coefficient | 2.1 × 109 | |

| Contribution to restoring force (for nonlinear) | 0.5 | |

| Constant (for nonlinear) | 0.01 | |

| Constant of hysteretic behavior | 1.0 | |

| Constant of hysteretic behavior | 0.5 | |

| Constant of hysteretic behavior | 0.5 | |

| Constant of hysteretic behavior | 5 |

| MLP Algorithm | MENC Algorithm | Decreasing Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| California earthquake | 23.20 mm | 11.17 mm | 51.84% |

| Northridge earthquake | 30.54 mm | 17.31 mm | 43.32% |

| Landers earthquake | 14.89 mm | 6.72 mm | 54.83% |

| Cape earthquake | 14.15 mm | 9.04 mm | 36.09% |

| San Simeon earthquake | 7.92 mm | 6.60 mm | 16.77% |

| Loma Prieta earthquake | 12.56 mm | 6.34 mm | 49.55% |

| Max. Displacement (mm) | Max. Acceleration (m/s2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Control | Control by MENC | Decreasing Rate | Non-Control | Control by MENC | Decreasing Rate | |

| California earthquake | 40.10 | 11.17 | 72.14% | 9.38 | 2.66 | 71.64% |

| Northridge earthquake | 37.06 | 17.31 | 53.29% | 10.71 | 2.29 | 78.62% |

| Landers earthquake | 28.11 | 6.73 | 76.06% | 7.39 | 1.62 | 78.09% |

| Cape earthquake | 28.85 | 9.04 | 68.67% | 8.23 | 1.85 | 77.52% |

| San Simeon earthquake | 25.96 | 6.60 | 74.58% | 7.12 | 0.82 | 88.48% |

| Loma Prieta earthquake | 28.97 | 6.34 | 78.12% | 7.12 | 1.08 | 84.83% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, S.; Sung, D. Modal-Energy-Based Neuro-Controller for Seismic Response Reduction of a Nonlinear Building Structure. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9204443

Chang S, Sung D. Modal-Energy-Based Neuro-Controller for Seismic Response Reduction of a Nonlinear Building Structure. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(20):4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9204443

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Seongkyu, and Deokyong Sung. 2019. "Modal-Energy-Based Neuro-Controller for Seismic Response Reduction of a Nonlinear Building Structure" Applied Sciences 9, no. 20: 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9204443