Spatial Resolutions of On-Axis and Off-Axis Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Methods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. TKD

3. Results and Discussion

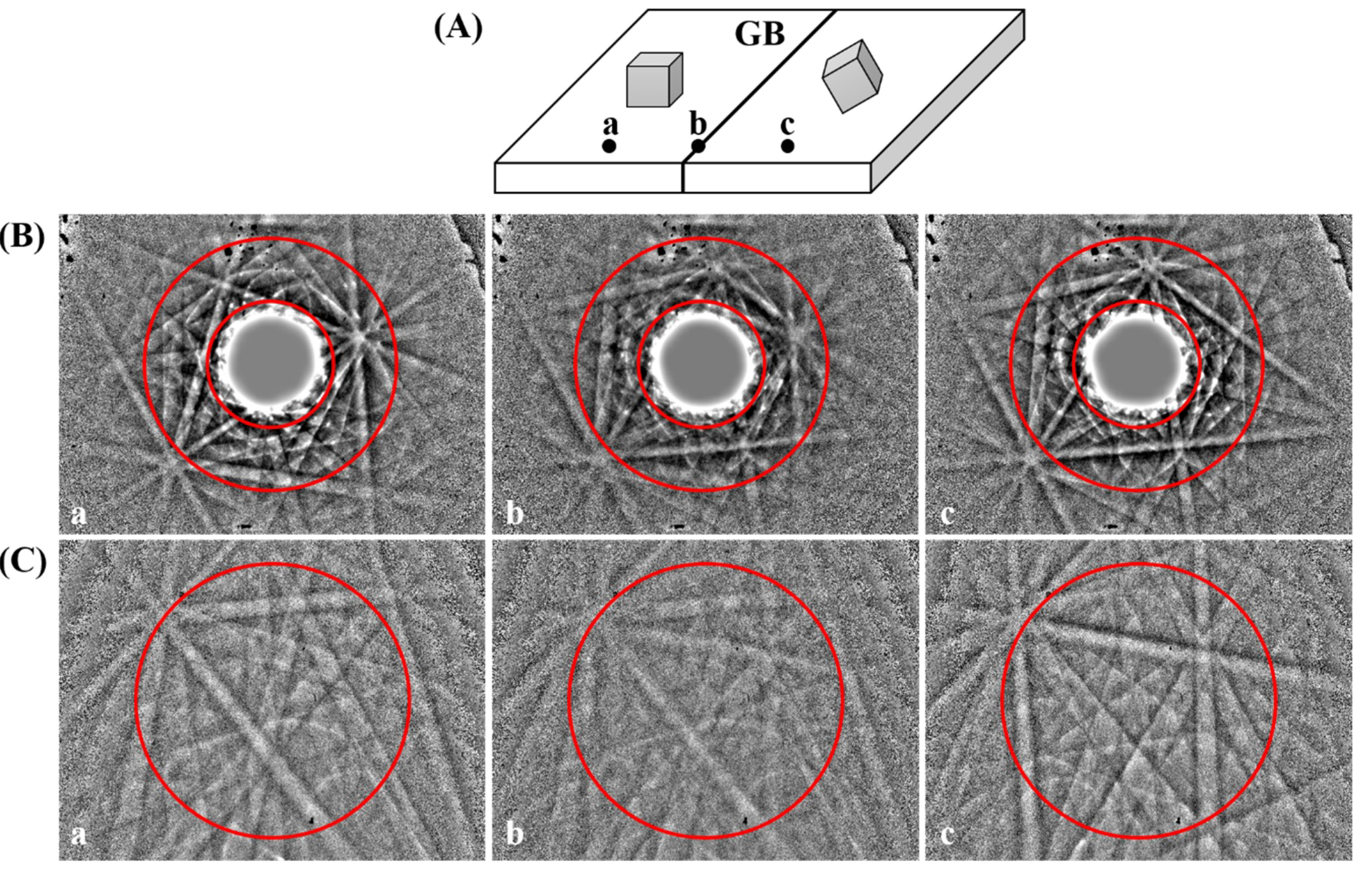

3.1. Quantitative Evaluation of the Spatial Resolution

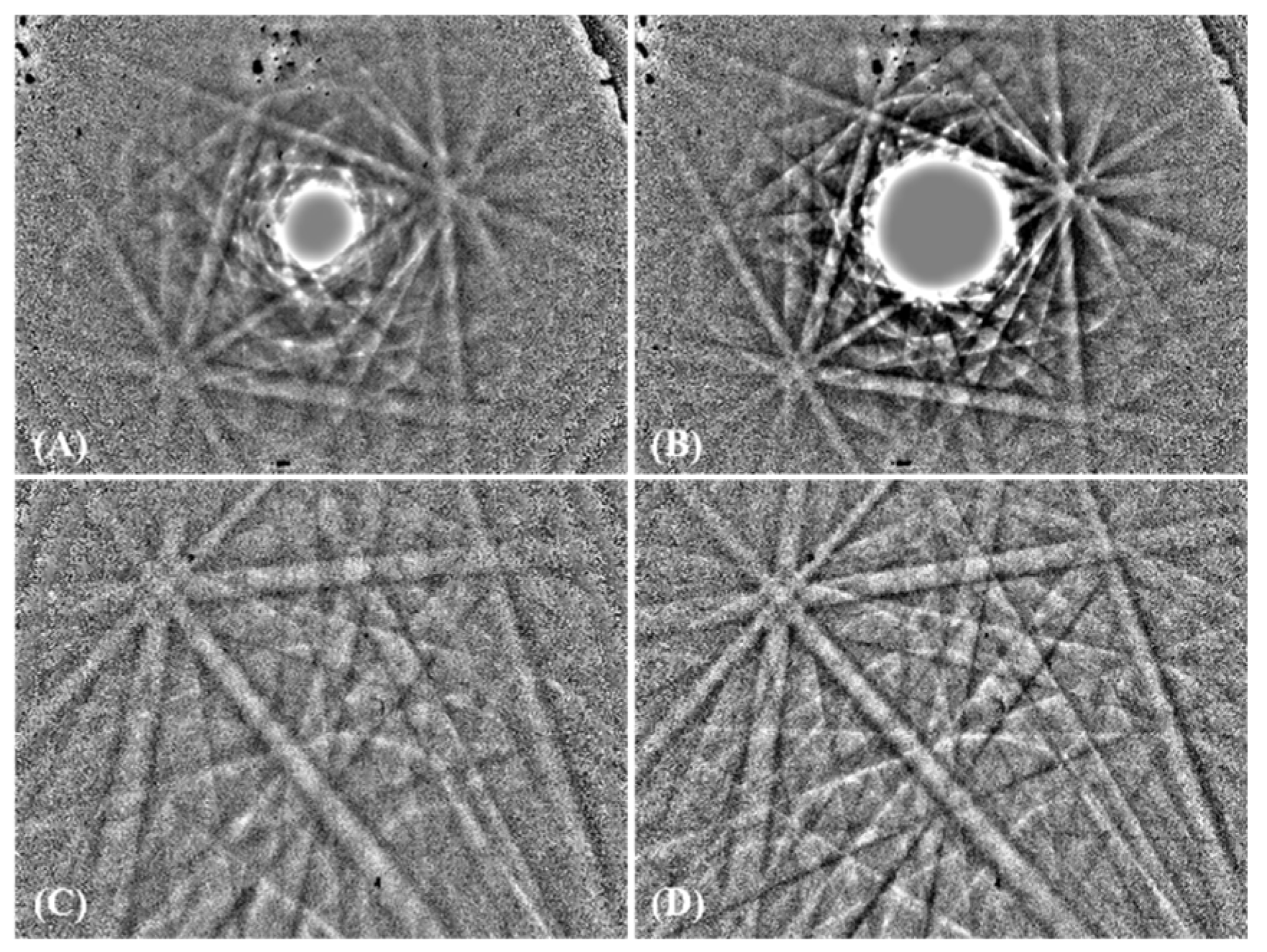

3.2. Difference in Spatial Resolution between the On-Axis and Off-Axis TKD Methods

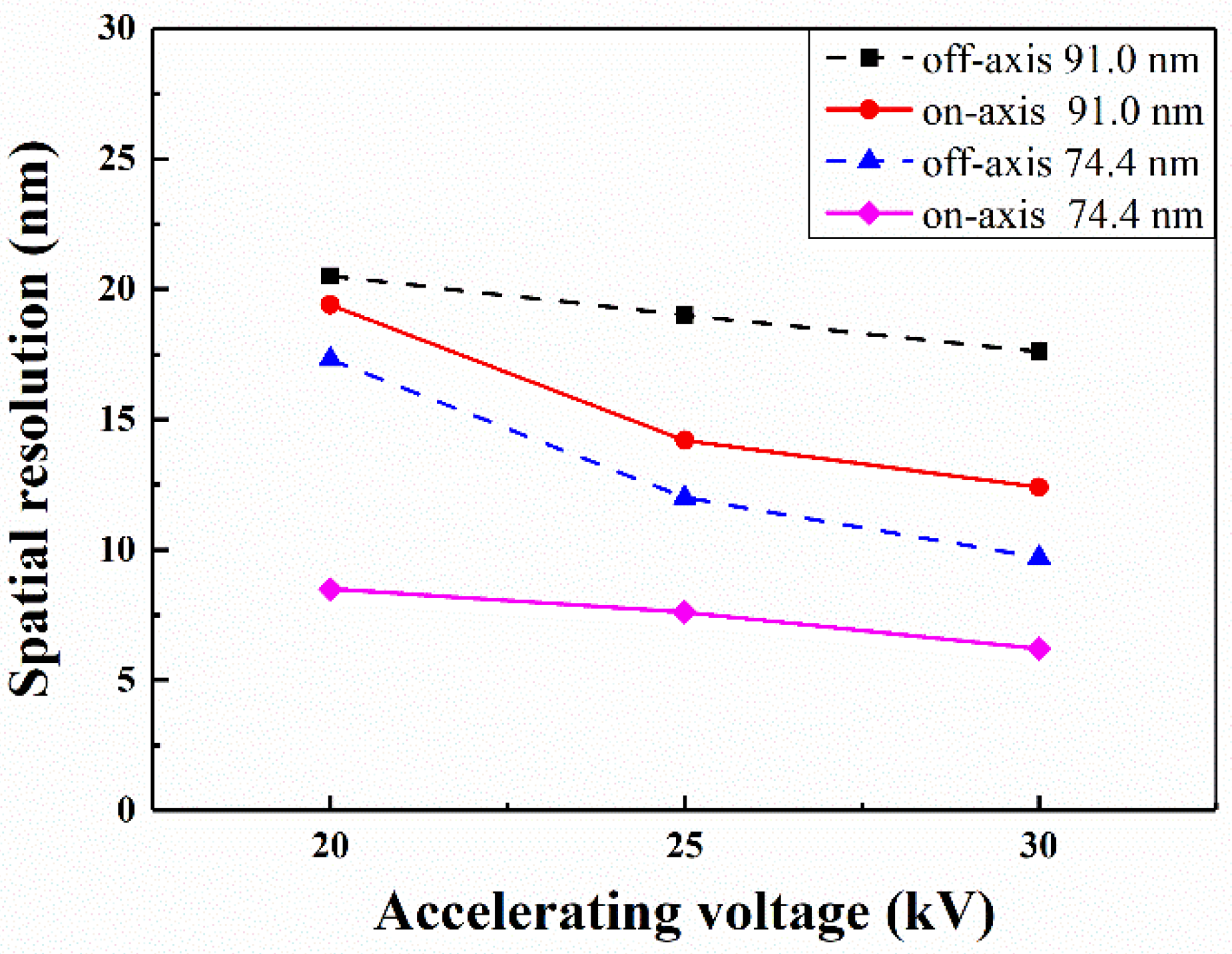

3.3. Effects of the Accelerating Voltage and Specimen Thickness on the On-Axis and Off-Axis TKDs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, S.I.; Nowell, M.M.; Lindeman, S.P.; Camus, P.P.; De Graef, M.; Jackson, M.A. Introduction and comparison of new EBSD post-processing methodologies. Ultramicroscopy 2015, 159, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keller, R.R.; Geiss, R.H. Transmission EBSD from 10 nm domains in a scanning electron microscope. J. Microsc. 2012, 245, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundenberger, J.J.; Bouzy, E.; Goran, D.; Guyon, J.; Yuan, H.; Morawiec, A. Orientation mapping by transmission-SEM with an on-axis detector. Ultramicroscopy 2016, 161, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Brodu, E.; Chen, C.; Bouzy, E.; Fundenberger, J.J.; Toth, L.S. On-axis versus off-axis Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction technique: Application to the characterisation of severe plastic deformation-induced ultrafine-grained microstructures. J. Microsc. 2017, 267, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niessen, F.; Burrows, A.; Fanta, A.B.d.S. A systematic comparison of on-axis and off-axis transmission Kikuchi diffraction. Ultramicroscopy 2018, 186, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodu, E.; Bouzy, E.; Fundenberger, J.-J.; Guyon, J.; Guitton, A.; Zhang, Y. On-axis TKD for orientation mapping of nanocrystalline materials in SEM. Mater. Charact. 2017, 130, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimby, P.W. Orientation mapping of nanostructured materials using transmission Kikuchi diffraction in the scanning electron microscope. Ultramicroscopy 2012, 120, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodusch, N.; Demers, H.; Gauvin, R. Nanometres-resolution Kikuchi patterns from materials science specimens with transmission electron forward scatter diffraction in the scanning electron microscope. J. Microsc. 2013, 250, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimby, P.W.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Hemker, K.J.; Lian, J.; Liao, X.; Rottmann, P.; Samudrala, S.; Sun, J.; et al. Characterizing deformed ultrafine-grained and nanocrystalline materials using transmission Kikuchi diffraction in a scanning electron microscope. Acta Mater. 2014, 62, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Hua, J.J.; Lin, C.C.; Jiang, C.F.; Zeng, Y. Application of Transmission Electron Backscattered Diffraction in Nanomaterials Research. J. Inorg. Mater. 2015, 30, 833–837. [Google Scholar]

- Proust, G.; Trimby, P.; Piazolo, S.; Retraint, D. Characterization of Ultra-fine Grained and Nanocrystalline Materials Using Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, C.; Basinger, J.A.; Nowell, M.M.; Fullwood, D.T. Five-Parameter Grain Boundary Inclination Recovery with EBSD and Interaction Volume Models. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, 4165–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaefferer, S. On the formation mechanisms, spatial resolution and intensity of backscatter Kikuchi patterns. Ultramicroscopy 2007, 107, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Kuo, J.-C.; Wu, W.-T. Effect of microscopic parameters on EBSD spatial resolution. Ultramicroscopy 2011, 111, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isabell, T.C.; Dravid, V.P. Resolution and sensitivity of electron backscattered diffraction in a cold field emission gun SEM. Ultramicroscopy 1997, 67, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingley, D. Progressive steps in the development of electron backscatter diffraction and orientation imaging microscopy. J. Microsc. Oxf. 2004, 213, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.X.; Kenik, E.A.; Alexander, K.B.; Goyal, A. Exploring spatial resolution in electron back-scattered diffraction experiments via Monte Carlo simulation. Microsc. Microanal. 1998, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kuo, J.-C. The Effect of Atomic Mass on the Physical Spatial Resolution in EBSD. Microsc. Microanal. 2013, 19, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Kong, M.G.; Liu, Z.W.; Lin, C.C.; Zeng, Y. Effect of microscope parameter and specimen thickness of spatial resolution of transmission electron backscatter diffraction. J. Microsc. 2016, 264, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.-W.; Kuo, K.-W.; Kuo, J.-C.; Kuo, T.-Y. Effects of accelerating voltage and specimen thickness on the spatial resolution of transmission electron backscatter diffraction in Cu. Ultramicroscopy 2017, 177, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-W.; Kuo, J.-C.; Wang, S.-C. Resolution of transmission electron backscatter diffraction in aluminum and silver: Effect of the atomic number. Ultramicroscopy 2018, 193, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneddon, G.C.; Trimby, P.W.; Cairney, J.M. Transmission Kikuchi diffraction in a scanning electron microscope: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2016, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bremen, R.; Ribas Gomes, D.; de Jeer, L.T.H.; Ocelik, V.; De Hosson, J.T.M. On the optimum resolution of transmission-electron backscattered diffraction (t-EBSD). Ultramicroscopy 2016, 160, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, K.P.; Keller, R.R.; Stoykovich, M.P. Specimen-thickness effects on transmission Kikuchi patterns in the scanning electron microscope. J. Microsc. 2014, 254, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Went, M.R.; Winkelmann, A.; Vos, M. Quantitative measurements of Kikuchi bands in diffraction patterns of backscattered electrons using an electrostatic analyzer. Ultramicroscopy 2009, 109, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Miao, H. Spatial Resolutions of On-Axis and Off-Axis Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Methods. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214478

Shen Y, Xu J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang J, Yu B, Zeng Y, Miao H. Spatial Resolutions of On-Axis and Off-Axis Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Methods. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214478

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Yitian, Jingchao Xu, Yongsheng Zhang, Yongzhe Wang, Jimei Zhang, Baojun Yu, Yi Zeng, and Hong Miao. 2019. "Spatial Resolutions of On-Axis and Off-Axis Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Methods" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4478. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214478