Research of Modal Analysis for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump

Abstract

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Modal Analysis of the Impeller

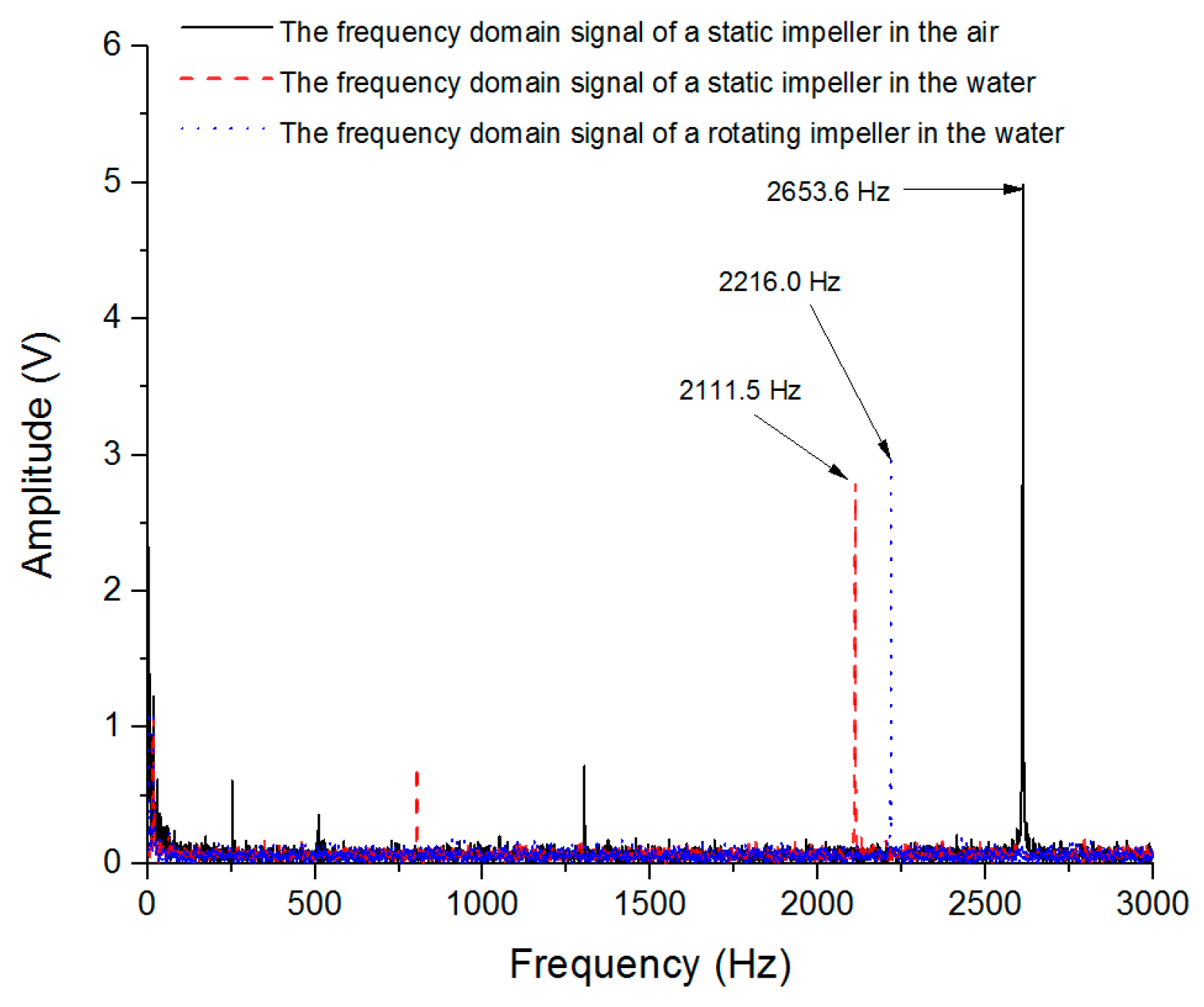

2.1. Modal Experiment

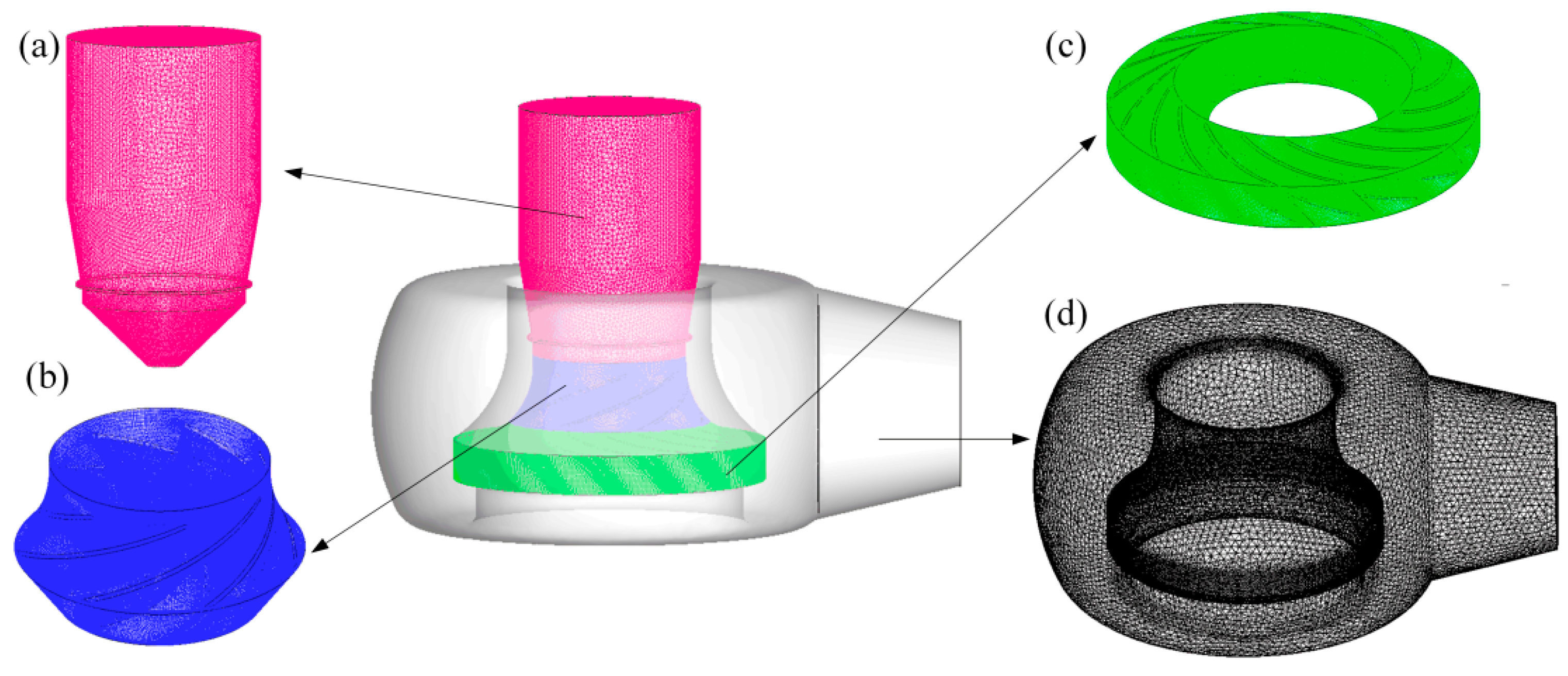

2.2. Modal Simulation

2.3. Result Analysis

3. Resonance Analysis of the RCP Impeller

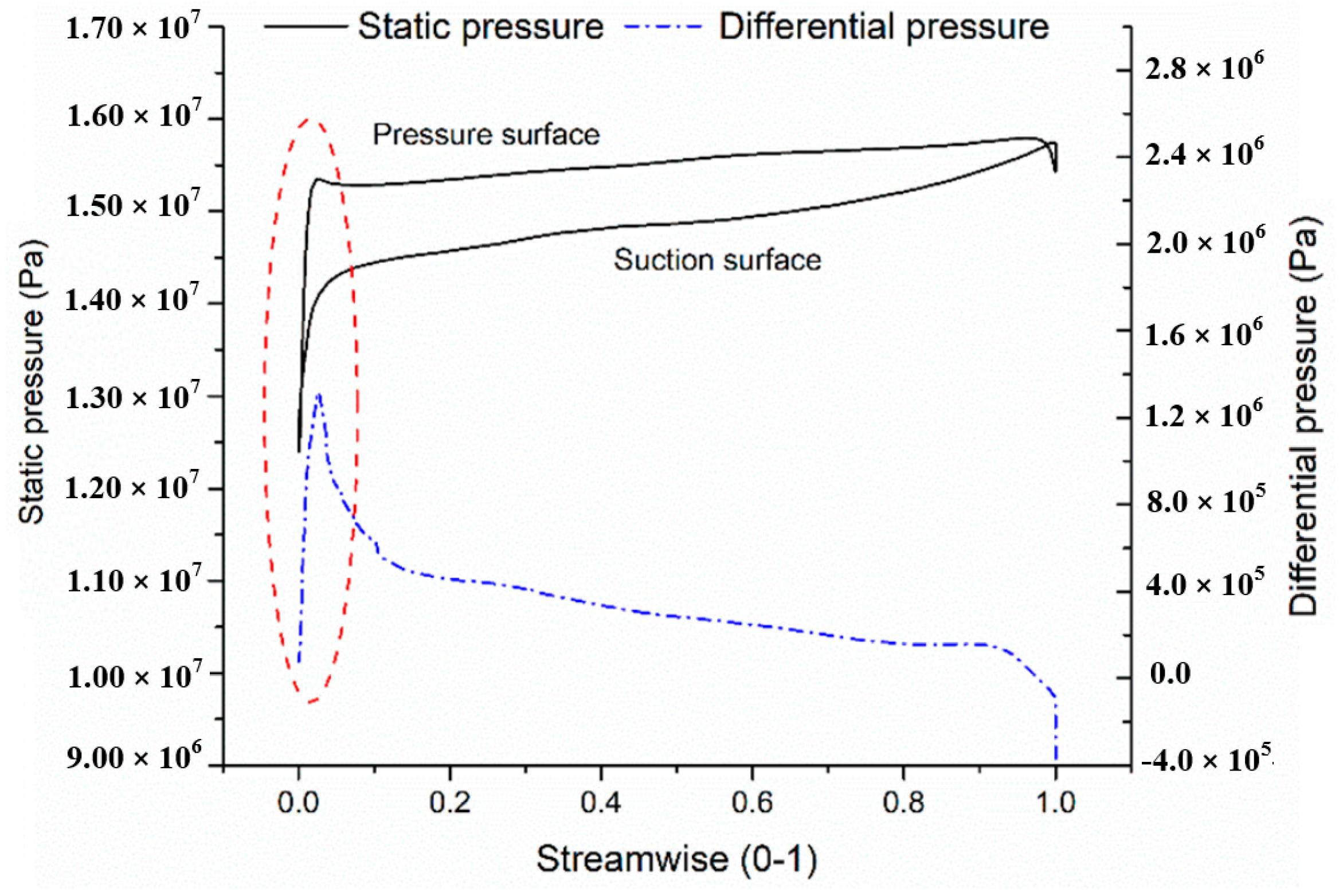

3.1. Flow Simulation of the RCP

3.2. Resonance Analysis of the Impeller

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Different Factors

4.2. Theoretical Expression of Natural Frequencies of the Impeller

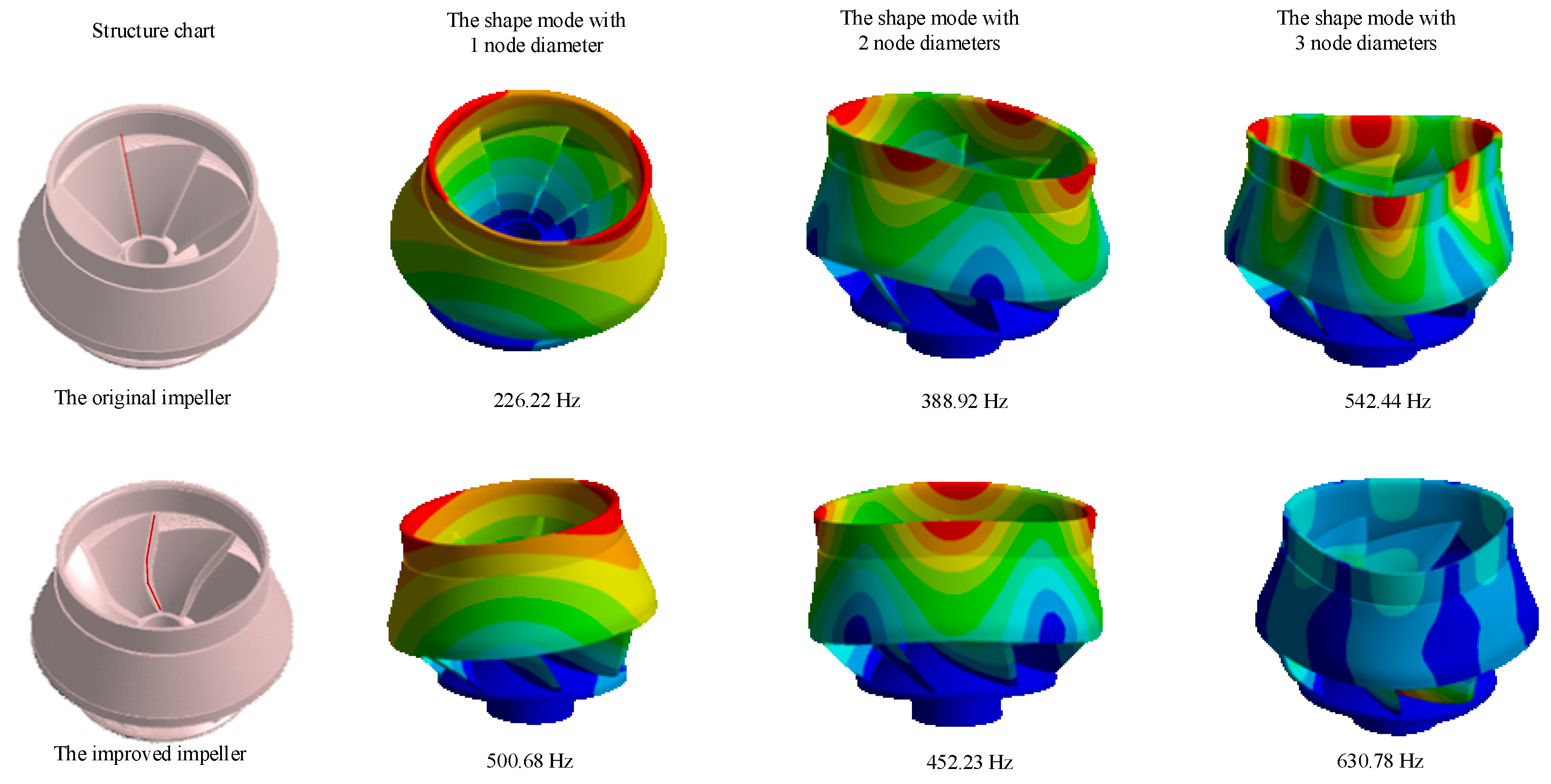

4.3. Improved Design of the RCP Impeller

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study provides a measure for testing vibration signals of an underwater rotator, and establishes a coupled simulation platform for modal analysis of the underwater impeller. Through comparative research, it is found that added mass and hydraulic load have a great influence on natural frequencies of the RCP impeller, but the impact of centrifugal force on them can be ignored. Therefore, it is necessary to take both added mass and hydraulic load into account for modal analysis of the impeller.

- (2)

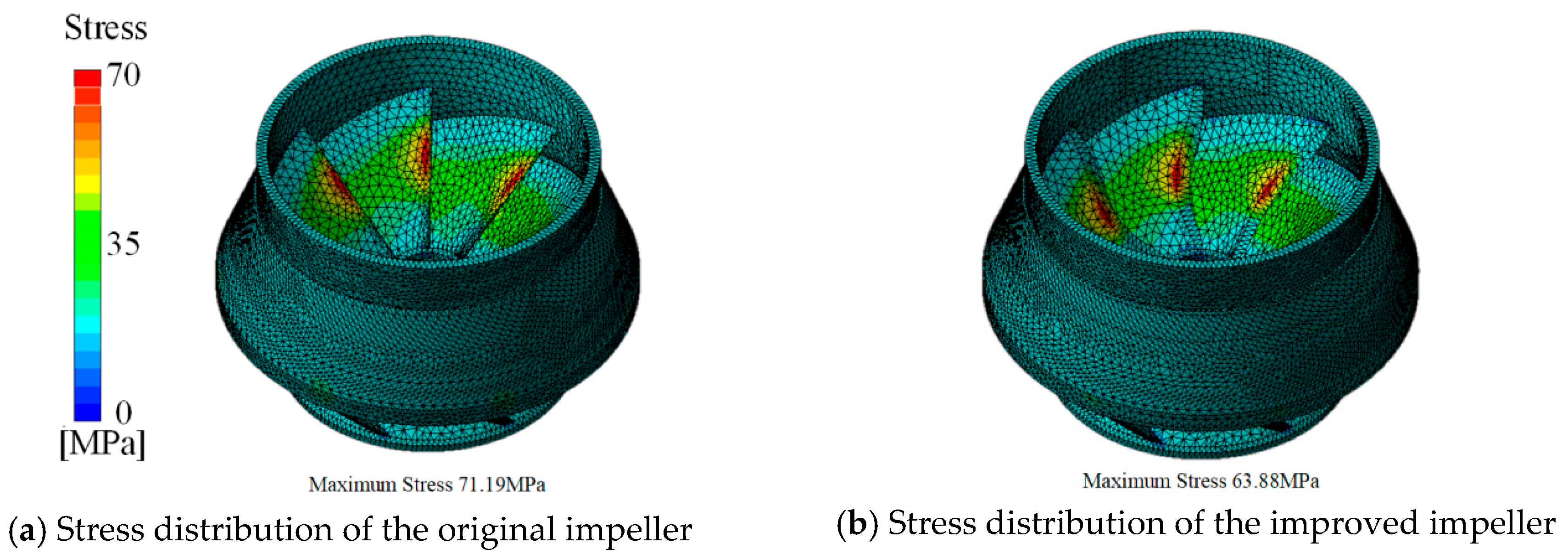

- Since hydraulic load stress concentration occurs in the middle of inlet edges, a solution of cutting inlet edges of blades is proposed to change natural frequencies the impeller. Without affecting hydraulic performance significantly, the measure can prevent hydraulic resonance and enhance structural strength. This indicates that it is feasible to alter the self-vibration mode of the impeller by hydraulic load redistribution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, H.; Gao, F.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Cao, X. Transient flow analysis in reactor coolant pump systems during flow coastdown period. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 2, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.F.; Zhao, G.; Xu, S.L.; Ye, Z. Numerical Analysis of Pressure Fluctuations Caused by Impeller-Diffuser Interaction in a Mixed Flow Reactor Coolant Pump. In Proceedings of the 2011 Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Wuhan, China, 25–28 March 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Ruan, X.; Xu, Z.; Fu, X. Analysis of pressure pulsation induced by rotor-stator interaction in nuclear reactor coolant pump. Shock Vib. 2017, 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.M. Irradiation swelling, creep, thermal shock and thermal cycling fatigue analysis of cylindrical controlled thermonuclear reactor first wall. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1974, 1, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Thakur, B.K.; Sullivan, W.E.; Donald, G. Resonance Identification for Impellers. In Proceedings of the 32nd Turbomachinery Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 8–11 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Valero, C.; Huang, X.; Egusquiza, E.; Farhat, M.; Avellan, F. Modal behavior of a reduced scale pump turbine impeller. Part II: Numerical simulation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ Sci. 2010, 12, 012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.W.; Rodríguez, C.G.; Egusquiza, E.; Escaler, X.; Avellan, F. Modal Response of Hydraulic Turbine Runners. In Proceedings of the 23rd IAHR Symposium on Hydraulic Machinery and Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 17–21 October 2006; pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Modal and Response Analysis of Rotating Blade. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, X.L.; Li, R.G. Experimental research on nature frequency of prestressed concrete beams. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2007, 2, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F. Investigation on Effect of Adhesive Water Condition to Wet Modal Response of Nuclear Coolant Pump Impeller. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; He, X.; Sun, T.; Wang, X. Research of Damping and Dynamic Stress for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump. In Proceedings of the ISROMAC 2017 (International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery), Maui, HI, USA, 16–21 December 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, M. Measurement experiment, using NI USB-6008 data acquisition. J. Electr. Electr. Eng. 2009, 1, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Ewins, D.J.; Saunders, H. Modal Testing: Theory and Practice; Research Studies Press: Letchworth, UK, 1984; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni, J.; Randall, R.B. The spectral kurtosis: Application to the vibratory surveillance and diagnostics of rotating machines. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2006, 2, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trethewey, M.W.; Friell, J.C.; Chandra, M.J.; Lebold, M.S. A spectral simulation approach to evaluate probabilistic measurement precision of a reactor coolant pump torsional vibration shaft crack monitoring system. J. Sound Vibr. 2008, 4, 1036–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.H.; Fink, K.D. Numerical Methods with MATLAB; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, D.; Wang, P.; Wong, X.; Wu, X. Design and Numerical Simulation on Guide Vane of AP1000 Reactor Coolant Pump. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2011; pp. 4016–4019. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. Railway Noise and Vibration: The Use of Appropriate Models to Solve Practical Problems. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Sound and Vibration, Beijing, China, 13–17 July 2014; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tan, X.; Xu, Z.; Ruan, X. Research on the non-uniform inflow characteristics of the canned nuclear coolant pump. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2018, 115, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jie, H.E. Effect of boric acid concentration on reactor coolant pump performance in PWRs. Nucl. Power Eng. 2011, 4, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Cao, H.; Ma, Q.; Yi, F.; Du, S. Relationship between rotor/vanes blade number and modal diameter number of bladed-disk coupling vibration. J. Aerosp. Power. 2019, 1, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gerolymos, G.A.; Michon, G.J.; Neubauer, J. Analysis and application of chorochronic periodicity in turbomachinery rotor/stator interaction computations. J. Propuls. Power. 2002, 6, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montante, G.; Lee, K.C.; Brucato, A.; Yianneskis, M. Numerical simulations of the dependency of flow pattern on impeller clearance in stirred vessels. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 12, 3751–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.E.D.; Johnson, D.C. The Mechanics of Vibration; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Beards, C. Structural Vibration: Analysis and Damping; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 58–69. [Google Scholar]

| Nodal Diameters | A. Static Impeller in the Air [Hz] | B. Static Impeller in Water [Hz] | C. Rotating Impeller in Water [Hz] (100 r/min) | D. Rotating Impeller in the Air [Hz] (1800 r/min) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3942 | 3152.6 | −20.0% | 3363.6 | −14.7% | 3942 | 0% |

| 1 | 2520.3 | 1974.2 | −21.7% | 2045.8 | −18.8% | 2517.7 | +0.001% |

| 2 | 5817.7 | 5003.4 | −14.0% | 5604.2 | −3.7% | 5812.7 | +0.001% |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Turbulence model | K-epsilon |

| Convergence precision | <1 × 10−5 |

| Rated speed of impeller | 1800 r/min |

| Inlet volume flowrate | 17,886 m3/h |

| Outlet static pressure | 15.5 MPa |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Ruan, X.; Xu, Z.; Fu, X. Research of Modal Analysis for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214551

Wang J, Wang P, Zhang X, Ruan X, Xu Z, Fu X. Research of Modal Analysis for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(21):4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214551

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiaming, Pengfei Wang, Xu Zhang, Xiaodong Ruan, Zhongbin Xu, and Xin Fu. 2019. "Research of Modal Analysis for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump" Applied Sciences 9, no. 21: 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214551

APA StyleWang, J., Wang, P., Zhang, X., Ruan, X., Xu, Z., & Fu, X. (2019). Research of Modal Analysis for Impeller of Reactor Coolant Pump. Applied Sciences, 9(21), 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9214551