Identification and Description of Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Densmore’s Collection and Analysis of Native American Music

3. Outlier Identification and Description with Infrequent Contrast Patterns

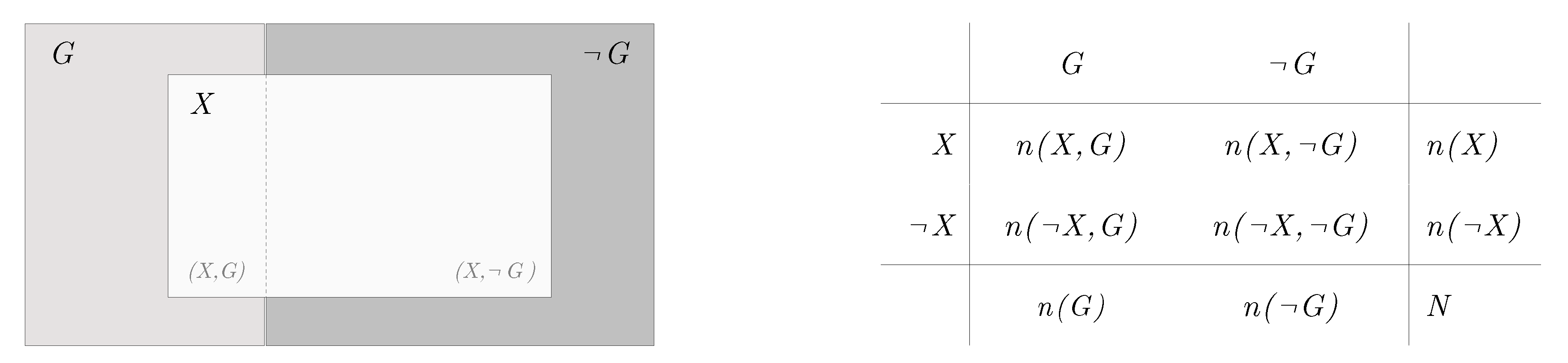

3.1. Data Representation and Organisation

3.2. Discovery of Significantly Infrequent Contrast Patterns

3.3. Pattern Pruning and Outlier Detection

4. Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music

4.1. Outlier Songs with Unusual Features

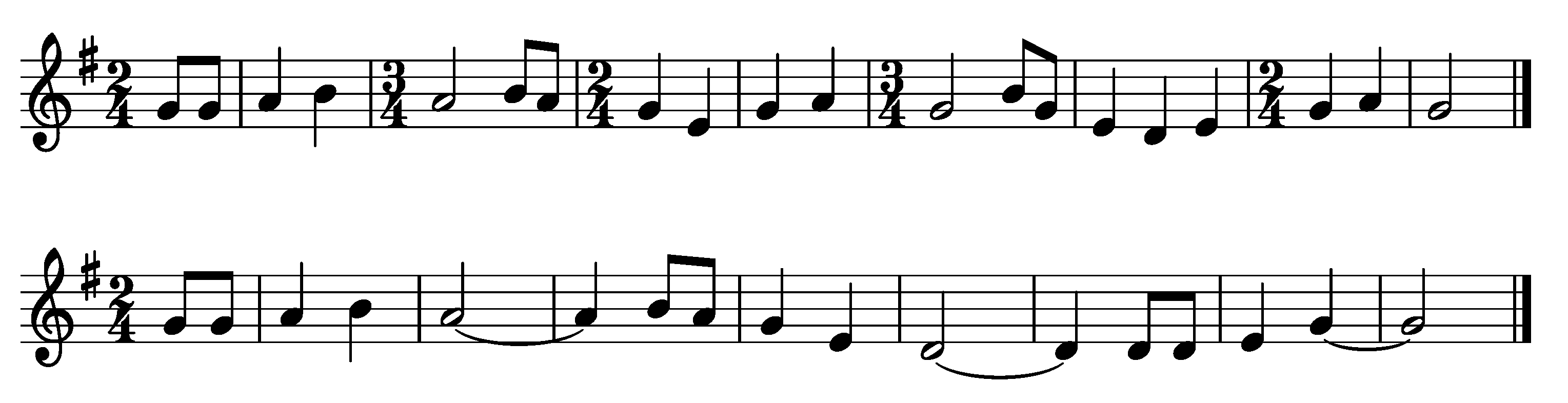

4.2. Outlier Songs with Unusual Feature Combinations

4.3. Performance and Encoding

4.4. Context

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tzanetakis, G.; Kapur, A.; Schloss, W.; Wright, M. Computational ethnomusicology. J. Interdiscip. Music Stud. 2007, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fewkes, J.W. On the use of the phonograph in the study of the languages of American Indians. Science 1890, 15, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickwire, W. Theories of ethnomusicology and the North American Indian: Retrospective and critique. Can. Univ. Music Rev. 1985, 25, 186–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densmore, F. The study of Indian music. In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1941; pp. 527–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, C. Frances Densmore and the music of the American Indian. J. Am. Folk. 1946, 59, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densmore, F. The study of Indian music. Music. Q. 1915, 1, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densmore, F. Chippewa Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 45: Washington, DC, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Chippewa Music II; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 53: Washington, DC, USA, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Teton Sioux Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 61: Washington, DC, USA, 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Northern Ute Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 75: Washington, DC, USA, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Mandan and Hidatsa Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 80: Washington, DC, USA, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Papago Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 90: Washington, DC, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Pawnee Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 93: Washington, DC, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Menominee Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 102: Washington, DC, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Yuman and Yaqui Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 110: Washington, DC, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Nootka and Quileute Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 124: Washington, DC, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Choctaw Music; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 136: Washington, DC, USA, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Music of Acoma, Isleta, Cochiti and Zuñi Pueblos; Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 165: Washington, DC, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Densmore, F. Music of the Indians in our Western states. J. Am. Folk. 1957, 70, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubarth, K.; Shanahan, D.; Conklin, D. Supervised descriptive pattern discovery in Native American music. J. New Music Res. 2018, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeck, W. Struktur und Ähnlichkeit. Methoden Automatisierter Melodienanalyse; Kieler Schriften zur Musikwissenschaft 25, Bärenreiter: Kassel, Germany; Basel, Switzerland; London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Toiviainen, P.; Eerola, T. A method for comparative analysis of folk music based on musical feature extraction and neural networks. In Proceedings of the VII International Symposium on Systematic and Comparative Musicology/III International Conference on Cognitive Musicology, Jyväskylä, Finland, 16–19 August 2001; pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, Z. A systematic comparison of different European folk music traditions using self-organizing maps. J. New Music Res. 2006, 35, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, P.E.; Brown, S. Mapping music: Cluster analysis of song-type frequencies within and between cultures. Ethnomusicology 2014, 58, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.; Gómez, F.; Gómez, E.; Díaz-Báñez, J.M. Melodic contour and mid-level global features applied to the analysis of flamenco cantes. J. New Music Res. 2016, 45, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllensiefen, D.; Frieler, K. Optimizing measures of melodic similarity for the exploration of a large folk song database. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR 2004), Barcelona, Spain, 10–14 October 2004; pp. 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, E.; Haro, M.; Herrera, P. Music and geography: content description of musical audio from different parts of the world. In Proceedings of the 10th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2009), Kobe, Japan, 26–30 October 2009; pp. 753–758. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, D. Multiple viewpoint systems for music classification. J. New Music Res. 2013, 42, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kranenburg, P.; Volk, A.; Wiering, F. A comparison between global and local features for computational classification of folk song melodies. J. New Music Res. 2013, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.L.; Silla, C.N., Jr. Irish traditional ethnomusicology analysis using decision trees and high level symbolic features. In Proceedings of the 12th Sound and Music Computing Conference (SMC 2015), Maynooth, Ireland, 26 July–1 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, D.; Anagnostopoulou, C. Comparative pattern analysis of Cretan folk songs. J. New Music Res. 2011, 40, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikrakis, A.; Gómez, F.; Oramas, S.; Díaz-Báñez, J.M.; Mora, J.; Escobar, F.; Gómez, E.; Salamon, J. Tracking melodic patterns in flamenco singing by analyzing polyphonic music recordings. In Proceedings of the 13th International Society of Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2012), Porto, Portugal, 8–12 October 2012; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranenburg, P.; Volk, A.; Wiering, F. On identifying folk song melodies employing recurring motifs. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition and the 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for Cognitive Sciences of Music (ICMPC/ESCOM 2012), Thessaloniki, Greece, 23–28 July 2012; pp. 1057–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, D. Antipattern discovery in folk tunes. J. New Music Res. 2013, 42, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Srinivasamurthy, A.; Kumar, M.; Murthy, H.A.; Serra, X. Discovery of syllabic percussion patterns in tabla solo recordings. In Proceedings of the 16th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2015), Malaga, Spain, 26–30 October 2015; pp. 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, D.; Weisser, S. Pattern and antipattern discovery in Ethiopian bagana songs. In Computational Music Analysis; Meredith, D., Ed.; Springer International: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 393–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bountouridis, D.; Koops, H.V.; Wiering, F.; Veltkamp, R.C. Music outlier detection using multiple sequence alignment and independent ensembles. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Similarity Search and Applications (SISAP 2016), Tokyo, Japan, 24–26 October 2016; pp. 286–300. [Google Scholar]

- Flexer, A.; Pampalk, E.; Widmer, G. Novelty detection based on spectral similarity of songs. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR 2005), London, UK, 11–15 September 2005; pp. 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, L.K.; Lehn-Schiøler, T.; Petersen, K.B.; Arenas-García, J.; Larsen, J.; Jensen, S.H. Learning and clean-up in a large scale music database. In Proceedings of the 15th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO 2007), Poznan, Poland, 3–7 September 2007; pp. 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Livshin, A.; Rodet, X. Purging musical instrument sample databases using automatic musical instrument recognition methods. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Proc. 2009, 17, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashevich, H.; Dittmar, C. Improving GMM classifiers by preliminary one-class SVM outlier detection: Application to automatic music mood estimation. In Classification as a Tool for Research; Locarek-Junge, H., Weihs, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 775–782. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.C.; Wu, C.W.; Lu, C.T.; Lerch, A. Automatic outlier detection in music genre datasets. In Proceedings of the 17th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2016), New York, NY, USA, 7–11 August 2016; pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Panteli, M.; Benetos, E.; Dixon, S. A computational study on outliers in world music. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.; Pei, J.; Bailey, J.; Dong, G. Mining multidimensional contextual outliers from categorical relational data. Intel. Data Anal. 2015, 19, 1171–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.K.; Lavrač, N.; Gamberger, D.; Krstačić, A. CSM-SD: methodology for contrast set mining through subgroup discovery. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009, 42, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzmüller, M. Subgroup discovery—Advanced review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2015, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Xu, X.; Huang, J.Z.; Deng, S. FP-Outlier: Frequent pattern based outlier detection. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2005, 2, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoting, A.; Otey, M.E.; Parthasarathy, S. LOADED: link-based outlier and anomaly detection in evolving data sets. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM 2004), Brighton, UK, 1–4 November 2004; pp. 387–390. [Google Scholar]

- Narita, K.; Kitagawa, H. Outlier detection for transaction databases using association rules. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Conference on Web-Age Information Management (WAIM 2008), Zhangjiajie, China, 20–22 July 2008; pp. 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, P.K.; Mahoney, M.V.; Arshad, M.H. A Machine Learning Approach to Anomaly Detection; Technical Report CS-2003-06; Florida Institute of Technology: Melbourne, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.; Schneider, J.; Neill, D.B. Anomaly pattern detection in categorical datasets. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’08), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 August 2008; pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Angiulli, F.; Fassetti, F.; Palopoli, L. Discovering characterizations of the behavior of anomalous sub-populations. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2013, 25, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulse, J.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Class noise detection using frequent itemsets. Intel. Data Anal. 2006, 10, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubarth, K.; Conklin, D. Contrast pattern mining in folk music analysis. In Computational Music Analysis; Meredith, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 393–424. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, D.; Shanahan, E. The Densmore collection of Native American songs: a new corpus for studies of effects of geography and social function in music. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference for Music Perception and Cognition (ICMPC 2014), Seoul, Korea, 4–8 August 2014; pp. 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, D.; Neubarth, K.; Conklin, D. Mining musical traits of social functions in Native American music. In Proceedings of the 17th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2016), New York, NY, USA, 7–11 August 2016; pp. 681–687. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, V.L. American Indian musics, past and present. In The Cambridge History of American Music; Nicholls, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Group | Location of Reservations | No. Songs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910/13 | Chippewa I/II | Minnesota (incl. 20 Sioux songs recorded by Chippewa) | 360 |

| 1918 | Teton Sioux | North and South Dakota | 240 |

| 1922 | Northern Ute | Utah | 110 |

| 1923 | Mandan and Hidatsa | North Dakota | 110 |

| 1929 | Papago | Arizona | 167 |

| 1929 | Pawnee | Oklahoma | 86 |

| 1932 | Menominee | Wisconsin | 140 |

| 1932 | Yuman and Yaqui | California (Yuma, Mohave); Arizona (Cocopa, Yaqui) | 130 |

| 1939 | Nootka and Quileute | Washington | 210 |

| 1943 | Choctaw | Mississippi | 65 |

| 1957 | Pueblos | New Mexico (recorded in Washington and Wisconsin) | 82 |

| Attribute | Description | Attribute | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| tonality | tonality (third above keynote) | structure | relation between accented tones |

| firstReKey | first tone relative to keynote | firstDir | direction of first melodic progression |

| lastReKey | last tone relative to keynote | firstMetr | metrical position of first tone |

| lastReCompass | last tone relative to compass | initMetre | metre of first measure |

| compass | compass of song | metreChange | change of metre (measure-lengths) |

| material | tone material, scale | rhythmUnit | repeated rhythmic unit(s) |

| accidentals | chromatic alterations |

| Group | Outlier Description | Outliers | Group | Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papago | {firstReKey: third_or_fifth_above_octave} | 1 | ||

| Choctaw | {compass: nine_to_twelve_tones} | 2 | ||

| Papago | {firstReKey: octave, lastReKey: keynote} | 2 | ||

| Pueblos | {metreChange: no} | 2 | ||

| Teton Sioux | {compass: four_or_less_tones} | 2 | ||

| Chippewa | {lastReKey; irregular} | 3 | ||

| Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: third_or_fifth_above_octave} | 3 | ||

| Yuman and Yaqui | {compass: nine_to_twelve_tones} | 3 | ||

| Chippewa | {firstReKey: keynote} | 8 | ||

| Choctaw | {firstMetr: unaccented} | 8 | ||

| Mandan and Hidatsa | {lastReCompass: containing_lower} | 9 | ||

| Papago | {structure: harmonic} | 9 | ||

| Nootka and Quileute | {structure: melodic_with_harmonic_framework} | 10 | ||

| Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: octave} | 12 | ||

| Menominee | {compass: five_to_eight_tones, firstDir: up} | 14 |

| Song | Group | Outlier Description |

|---|---|---|

| ID857 | Mandan and Hidatsa | {lastReCompass: containing_lower} “The ascent of a semitone to the final tone is somewhat unusual.” ([11], p. 136) |

| ID907 | Mandan and Hidatsa | {lastReCompass: containing_lower} “In this song there is no ascending sequence between accented tones, though the final interval is an ascending interval.” ([11], p. 152) |

| ID1027 | Papago | {structure: harmonic} “The song is harmonic in structure, which is unusual in the present series.” ([12], p. 112) |

| ID1241 | Yuman and Yaqui | {compass: nine_to_twelve_tones} “This song has a compass of 10 tones, which is larger than any other song under present analysis.” ([15], p. 196) |

| ID1303 | Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: octave}, {structure:melodic_with_harmonic_framework} |

| ID1337 | Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: third_or_fifth_above_octave} “It is a lively, interesting melody, with a compass of 10 tones, and begins on the highest tone of the compass, which is unusual.” ([16], p. 93) |

| ID1345 | Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: third_or_fifth_above_octave} “This song has a compass of 10 tones, beginning on the highest tone of the compass and ending on the lowest.” ([16], p. 326) |

| ID1474 | Nootka and Quileute | {firstReKey: octave}, {structure: melodic_with_harmonic_framework} |

| ID1907 | Pueblos | {metreChange: no} |

| ID2357 | Choctaw | {compass: nine_to_twelve_tones} “This song has a compass of 11 tones, which is the largest in the Choctaw songs.” ([17], p. 140) |

| Song | Group | Outlier Description |

|---|---|---|

| ID930 | Papago | {firstReKey: octave, lastReKey: keynote} “The melodic formation of this song is unusual. The song begins with a half note on the highest tone of the compass. This tone is the keynote [octave] and does not occur again in the song.” ([12], p. 200) |

| ID954 | Papago | {firstReKey: octave, lastReKey: keynote} “The song has a range of an octave and a steadily descending trend.” ([12], p. 37) |

| ID1540 | Menominee | {compass: five_to_eight_tones, firstDir: up} “The ascent of an octave at the opening was changed to a major sixth in the repetition of the melody.” ([14], p. 206) |

| ID1607 | Menominee | {compass: five_to_eight_tones, firstDir: up} “The opening intervals are unusual and comprise an ascending whole tone followed by an ascending seventh.” ([14], p. 66) |

| ID1609 | Menominee | {compass: five_to_eight_tones, firstDir: up} “This song resembles others of the present group in having a compass of eight tones, lying partly above and partly below the keynote.” ([14], p. 67) |

| ID1632 | Menominee | {compass: five_to_eight_tones, firstDir: up} “It is interesting to note the ascent of an octave within three intervals at the opening of the song and in one interval, midway the length of the song.” ([14], p. 207) |

| Song | Group | Outlier Description |

|---|---|---|

| ID70 | Chippewa | {lastReKey: irregular} “The tonality of this song is obscure. […]” ([7], p. 80) |

| ID125 | Chippewa | {lastReKey: irregular} “[The song] is interesting in that the singer began the last half slightly too high, thus changing the key from C minor to C sharp minor.” ([7], p. 59) |

| ID194 | Chippewa | {lastReKey: irregular} “This song offers a distinct problem in tonality. The tones are those of the fourth five-toned scale on G flat, but the first part of the song affiliates only with the chords of the key of D flat and the last part only with the chords of the key of G flat. Neither key is well established by the melody.” ([7], p. 100) |

| ID820 | Mandan and Hidatsa | {lastReCompass: containing_lower} “The descent of an octave in the third measure from the last extends the compass of the song to 13 tones. The low tone [the only tone lower than the last tone] is short and was simply touched by the voice, as it was below the singer’s natural range.” ([11], p. 93) |

| ID2271 | Choctaw | {firstMetr: unaccented} “Two renditions of this song were recorded and both are presented […]. The first rendition contains an introductory phrase which is indicated as a rhythmic unit. This does not occur in the repetition of the song.” ([17], p. 169) |

| Song | Group | Outlier Description |

|---|---|---|

| ID102 | Chippewa | {firstReKey: keynote} “This lullaby is very old and is widely used among the Chippewa […].” ([7], p. 163) |

| ID280 | Chippewa | {firstReKey: keynote} “This melody contains three peculiarities which rarely occur in Chippewa songs. First, it begins and ends on the same tone [the keynote].” ([8], p. 139) |

| ID447 | Chippewa | {firstReKey: keynote} “This lullaby was first recorded at White Earth, Minnesota (Bulletin 45, p. 163). On comparing the two transcriptions it will be seen that the first four measures are identical and that the latter parts differ, though both renditions end on the same tone.” ([8], p. 241) |

| ID679 | Teton Sioux | {compass: four_or_less_tones} “This and song No. 204 [ID682] are the only songs in the present series having a compass of but four tones […].” ([9], p. 493) |

| ID682 | Teton Sioux | {compass: four_or_less_tones} “[…] the song having a compass of four tones.” ([9], p. 482) |

| ID1289 | Yuman and Yaqui | {compass: nine_to_twelve_tones} “The compass is nine tones, the only songs in this work which have a compass of more than an octave being this and No. 124 […].” ([15], p. 183) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neubarth, K.; Conklin, D. Identification and Description of Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030552

Neubarth K, Conklin D. Identification and Description of Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music. Applied Sciences. 2019; 9(3):552. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030552

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeubarth, Kerstin, and Darrell Conklin. 2019. "Identification and Description of Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music" Applied Sciences 9, no. 3: 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030552

APA StyleNeubarth, K., & Conklin, D. (2019). Identification and Description of Outliers in the Densmore Collection of Native American Music. Applied Sciences, 9(3), 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9030552