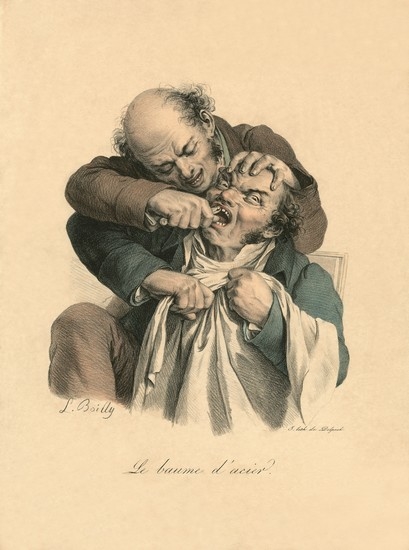

Faces of Pain during Dental Procedures: Reliability of Scoring Facial Expressions in Print Art

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measurement Instrument

2.3. Training

2.4. Reliability Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intra-Observer Reliability

3.2. Inter-Observer Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lipton, J.A.; Ship, J.A.; Larach-Robinson, D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1993, 124, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, R.; Klasser, G.D. Diagnosis and Management of TMDs. In Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management, 5th ed.; de Leeuw, R., Ed.; Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.: Hanover Park, IL, USA, 2013; pp. 127–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Weijenberg, R.A.; Scherder, E.J. Topical review: Orofacial pain in dementia patients. A diagnostic challenge. J. Orofac. Pain 2011, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Delwel, S.; Weijenberg, R.A.F.; Scherder, E.J.A. Orofacial pain and mastication in dementia. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; Achterberg, W.P.; Rijkmans, W.E.; Tukker-van Vuuren, S.A.; Delwel, S.; de Vet, H.C.; Lobbezoo, F.; de Waal, M.W. Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC): Content validity of the Dutch version of a new and universal tool to measure pain in dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delwel, S.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Maier, A.B.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Lobbezoo, F.; Scherder, E.J.A. Psychometric evaluation of the Orofacial Pain Scale for Non-Verbal Individuals as a screening tool for orofacial pain in people with dementia. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van de Rijt, L.J.; Weijenberg, R.A.; Feast, A.R.; Delwel, S.; Vickerstaff, V.; Lobbezoo, F.; Sampson, E.L. Orofacial pain during rest and chewing in dementia patients admitted to acute hospital wards: Validity testing of the orofacial pain scale for non-verbal individuals. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2019, 33, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, M.; de Waal, M.W.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Lobbezoo, F.; Sampson, E.L.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; Defrin, R.; Invitto, S.; Konstantinovic, L.; et al. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta-tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simon, L. Overcoming Historical Separation between Oral and General Health Care: Interprofessional Collaboration for Promoting Health Equity. AMA J. Ethics 2016, 18, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schade, G.J. Tandheelkunde in de Prentkunst, 1st ed.; Uitgeverij THOTH: Bussum, The Netherlands, 2014; p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- Schade, G.J. The History of Dentistry: In 256 Prints, 1470–1870; Uitgever Gert Schade: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ohrbach, R.; Borner, J.; Jezewski, M.; John, M.T.; Lobbezoo, F. Guidelines for Establishing Cultural Equivalency of Instruments; University at Buffalo: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- LOCOmotion, PAIC 15—Herken Pijn Bij Dementie. Available online: https://www.free-learning.nl/modules/paic15/start.html (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, M.W.; Visscher, C.; Delwel, S.; van der Steen, J.T.; Pieper, M.J.; Scherder, E.J.; Achterberg, W.P.; Lobbezoo, F. Orofacial pain during mastication in people with dementia: Reliability testing of the Orofacial Pain Scale for Non-Verbal Individuals (OPS-NVI). Behav. Neurol. 2016, 2016, 3123402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Waal, M.W.M.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Konstantinovic, L.; de Tommaso, M.; Fischer, T.; Lukas, A.; Kunz, M.; Lautenbacher, S.; et al. Observational pain assessment in older persons with dementia in four countries: Observer agreement of items and factor structure of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Obs. 1 | Obs. 2 | Expert | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facial expressions | |||

| Frowning | 0.907 | 0.915 | 0.970 |

| Narrowing of the eyes | 0.866 | 0.924 | 0.955 |

| Raising the upper lip | 0.748 | 0.771 | 0.908 |

| Tense impression | 0.857 | 0.914 | 0.875 |

| Body movements | |||

| Freezing | 0.833 | 0.845 | 0.875 |

| Guarding | 0.933 | 0.988 | 0.933 |

| Resisting care | 0.887 | 0.991 | 0.899 |

| Rubbing | * | * | * |

| Restlessness | * | * | * |

| Obs. 1 vs. Obs. 2 | Obs. 1 vs. Expert | Obs. 2 vs. Expert | Obs. 1 vs. Gold Standard | Obs. 2 vs. Gold Standard | Expert vs. Gold Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial expressions | ||||||

| Frowning | 0.657 | 0.886 | 0.827 | 0.853 | 0.855 | 0.970 |

| Narrowing of the eyes | 0.940 | 0.861 | 0.858 | 0.795 | 0.873 | 0.943 |

| Raising the upper lip | 0.604 | 0.650 | 0.884 | 0.789 | 0.718 | 0.856 |

| Tense impression | 0.766 | 0.656 | 0.722 | 0.782 | 0.836 | 0.884 |

| Body movements | ||||||

| Freezing | 0.448 | 0.416 | 0.452 | 0.347 | 0.000 | 0.630 |

| Guarding | 0.895 | 0.651 | 0.805 | 0.933 | 0.957 | 0.811 |

| Resisting care | 0.596 | 0.703 | 0.754 | 0.722 | 0.708 | 0.779 |

| Rubbing | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Restlessness | * | * | * | * | * | * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lobbezoo, F.; Lam, X.M.; de la Mar, S.; van de Rijt, L.J.M.; Kunz, M.; van Selms, M.K.A. Faces of Pain during Dental Procedures: Reliability of Scoring Facial Expressions in Print Art. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091207

Lobbezoo F, Lam XM, de la Mar S, van de Rijt LJM, Kunz M, van Selms MKA. Faces of Pain during Dental Procedures: Reliability of Scoring Facial Expressions in Print Art. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(9):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091207

Chicago/Turabian StyleLobbezoo, Frank, Xuan Mai Lam, Savannah de la Mar, Liza J. M. van de Rijt, Miriam Kunz, and Maurits K. A. van Selms. 2021. "Faces of Pain during Dental Procedures: Reliability of Scoring Facial Expressions in Print Art" Brain Sciences 11, no. 9: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091207

APA StyleLobbezoo, F., Lam, X. M., de la Mar, S., van de Rijt, L. J. M., Kunz, M., & van Selms, M. K. A. (2021). Faces of Pain during Dental Procedures: Reliability of Scoring Facial Expressions in Print Art. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091207