Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response and Attention: A Systemic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

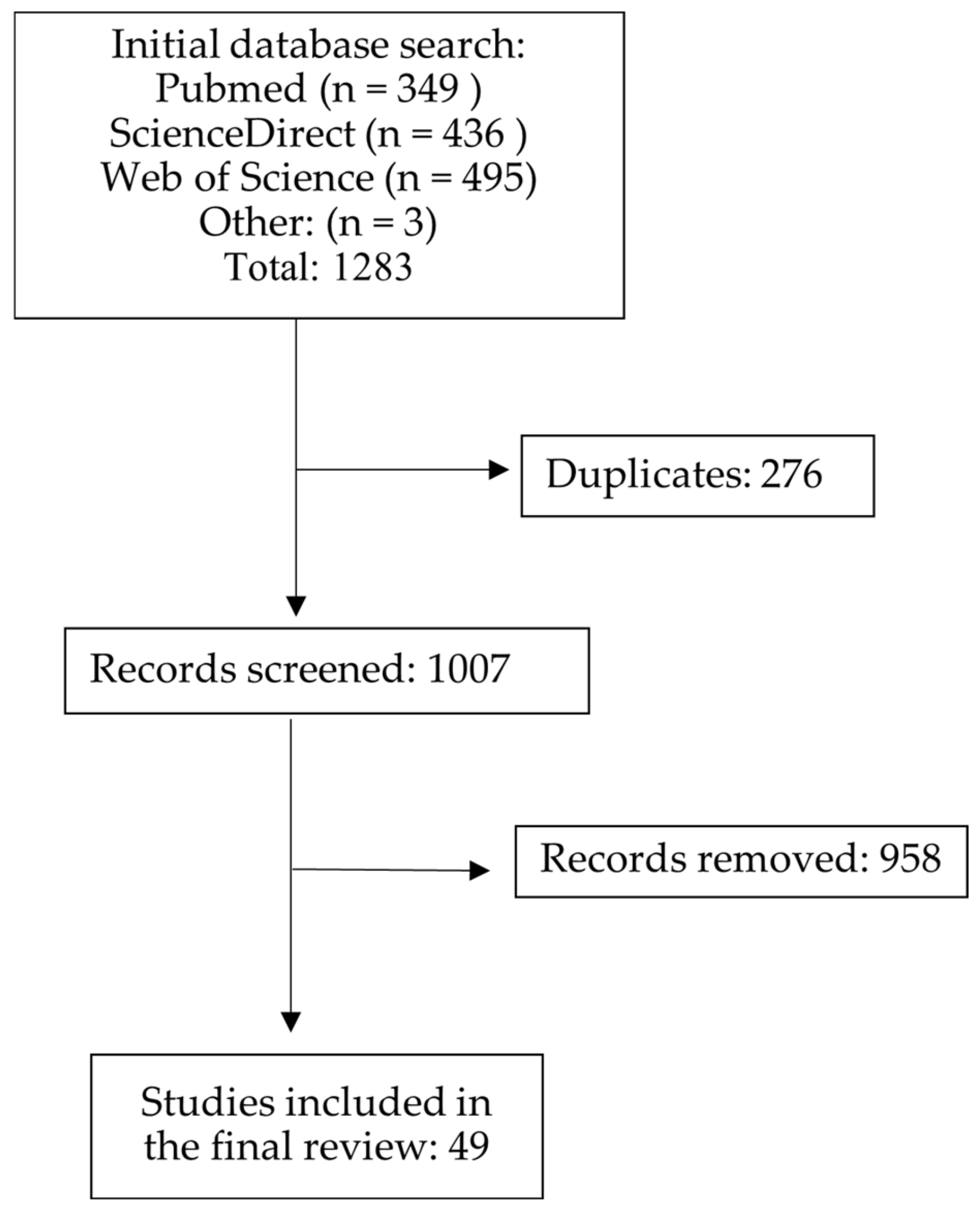

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Picton, T.W.; John, M.S.; Dimitrijevic, A.; Purcell, D. Human auditory steady-state responses: Respuestas auditivas de estado estable en humanos. Int. J. Audiol. 2003, 42, 177–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkelä, J.P.; Hari, R. Evidence for cortical origin of the 40 Hz auditory evoked response in man. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1987, 66, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, E.D.; Wouters, J.; Van Wieringen, A. Brain mapping of auditory steady-state responses: A broad view of cortical and subcortical sources. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 42, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, A.T.; Lins, O.; Van Roon, P.; Stapells, D.R.; Scherg, M.; Picton, T.W. Intracerebral sources of human auditory steady-state responses. Brain Topogr. 2002, 15, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmann, I.; Gutschalk, A. Potential fMRI correlates of 40-Hz phase locking in primary auditory cortex, thalamus and midbrain. NeuroImage 2011, 54, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.S.; O’Donnell, B.F.; Wallenstein, G.V.; Greene, R.W.; Hirayasu, Y.; Nestor, P.G.; Hasselmo, M.E.; Potts, G.F.; Shenton, M.E.; McCarley, R.W. Gamma Frequency–Range abnormalities to auditory stimulation in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Nagai, T.; Kirihara, K.; Koike, S.; Suga, M.; Araki, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Kasai, K. Differential alterations of auditory gamma oscillatory responses between Pre-Onset High-Risk individuals and First-Episode schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 26, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomura, S.; Onitsuka, T.; Tsuchimoto, R.; Nakamura, I.; Hirano, S.; Oda, Y.; Oribe, N.; Hirano, Y.; Ueno, T.; Kanba, S. Differentiation between major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder by auditory steady-state responses. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.W.; Rojas, D.C.; Reite, M.L.; Teale, P.D.; Rogers, S.J. Children and Adolescents with Autism Exhibit Reduced MEG Steady-State Gamma Responses. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, A.; Zarafshan, H.; Mohammadi, M.R. Visual and auditory steady-state responses in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 269, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.-H.; Mueller, N.E.; Spencer, K.M.; Mallya, S.G.; Lewandowski, K.E.; Norris, L.A.; Levy, D.L.; Cohen, B.M.; Öngür, D.; Hall, M.-H. Auditory steady state response deficits are associated with symptom severity and poor functioning in patients with psychotic disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 201, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, M.; Kirihara, K.; Koshiyama, D.; Fujioka, M.; Usui, K.; Uka, T.; Komatsu, M.; Kunii, N.; Araki, T.; Kasai, K. Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response as a neurophysiological marker for excitation and inhibition balance: A review for understanding schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2019, 51, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parciauskaite, V.; Pipinis, E.; Voicikas, A.; Bjekic, J.; Potapovas, M.; Jurkuvenas, V.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. Individual resonant frequencies at Low-Gamma range and cognitive processing speed. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, G.A.; Hsu, J.L.; Hsieh, M.H.; Meyer-Gomes, K.; Sprock, J.; Swerdlow, N.R.; Braff, D.L. Gamma band oscillations reveal neural network cortical coherence dysfunction in schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parciauskaite, V.; Voicikas, A.; Jurkuvenas, V.; Tarailis, P.; Kraulaidis, M.; Pipinis, E.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. 40-Hz auditory steady-state responses and the complex information processing: An exploratory study in healthy young males. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, M.; Price, G.; Lee, J.; Iyyalol, R.; Martin-Iverson, M. Dexamphetamine selectively increases 40 Hz auditory steady state response power to target and nontarget stimuli in healthy humans. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013, 38, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Briones, J.; Skosnik, P.D.; Mathalon, D.; Cahill, J.; Pittman, B.; Williams, A.; Sewell, R.A.; Ranganathan, M.; Roach, B.; Ford, J.; et al. Δ9-THC Disrupts Gamma (γ)-Band Neural Oscillations in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 2124–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktorin, V.; Griškova-Bulanova, I.; Voicikas, A.; Dojčánová, D.; Zach, P.; Bravermanová, A.; Andrashko, V.; Tylš, F.; Korčák, J.; Viktorinová, M.; et al. Psilocybin—Mediated attenuation of gamma band Auditory Steady-State responses (ASSR) is driven by the intensity of cognitive and emotional domains of psychedelic experience. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskova-Bulanova, I.; Griksiene, R.; Korostenskaja, M.; Ruksenas, O. 40 Hz auditory steady-state response in females: When is it better to entrain? Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2014, 74, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, U.; Binder, M. Low and medium frequency auditory steady-state responses decrease during NREM sleep. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 135, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Górska, U.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. 40 Hz auditory steady-state responses in patients with disorders of consciousness: Correlation between phase-locking index and Coma Recovery Scale-Revised score. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górska, U.; Binder, M. Low- and medium-rate auditory steady-state responses in patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness correlate with Coma Recovery Scale—Revised score. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 144, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäncke, L.; Mirzazade, S.; Shah, N.J. Attention modulates activity in the primary and the secondary auditory cortex: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in human subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 266, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Zatorre, R.J. Neural substrates for dividing and focusing attention between simultaneous auditory and visual events. NeuroImage 2006, 31, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomstein, S.; Yantis, S. Control of Attention Shifts between Vision and Audition in Human Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10702–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, J.; Gazzaley, A. Attention Distributed across Sensory Modalities Enhances Perceptual Performance. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12294–12302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, R.D.; Picton, T.W.; Hamel, G.; Campbell, K.B. Human auditory steady-state evoked potentials during selective attention. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1987, 66, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skosnik, P.D.; Krishnan, G.P.; O’Donnell, B.F. The effect of selective attention on the gamma-band auditory steady-state response. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 420, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzouni, L.; Ross, B.; Voss, P.; Lepore, F. Neuromagnetic auditory steady-state responses to amplitude modulated sounds following dichotic or monaural presentation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipinis, E.; Voicikas, A.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. Low and high gamma auditory steady-states in response to 440 Hz carrier chirp-modulated tones show no signs of attentional modulation. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 678, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, M.; Barbosa, C.; Valencia, M.; Pérez-Alcázar, M.; Iriarte, J.; Artieda, J. Effect of reduced attention on Auditory Amplitude-Modulation following responses: A study with Chirp-Evoked Potentials. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 25, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griskova-Bulanova, I.; Pipinis, E.; Voicikas, A.; Koenig, T. Global field synchronization of 40 Hz auditory steady-state response: Does it change with attentional demands? Neuroscience Letters 2018, 674, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, H.M.; Lee, A.K.C.; Shinn-Cunningham, B.G. Measuring auditory selective attention using frequency tagging. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, B.A.; Ren, X.; Longenecker, J.; Torrence, N.; Fishel, V.; Seebold, D.; Wang, Y.; Curtis, M.; Salisbury, D.F. Aberrant attentional modulation of the auditory steady state response (ASSR) is related to auditory hallucination severity in the first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 151, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, R.; Toffanin, P.; Harbers, M. Dynamic crossmodal links revealed by steady-state responses in auditory–visual divided attention. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2010, 75, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gander, P.E.; Bosnyak, D.J.; Wolek, R.; Roberts, L.E. Modulation of the 40-Hz auditory steady-state response by attention during acoustic training. Int. Congr. Ser. 2007, 1300, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, P.E.; Bosnyak, D.J.; Roberts, L.E. Acoustic experience but not attention modifies neural population phase expressed in human primary auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 2010, 269, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, P.E.; Bosnyak, D.J.; Roberts, L.E. Evidence for modality-specific but not frequency-specific modulation of human primary auditory cortex by attention. Hear. Res. 2010, 268, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskova-Bulanova, I.; Ruksenas, O.; Dapsys, K.; Maciulis, V.; Arnfred, S.M.H. Distraction task rather than focal attention modulates gamma activity associated with auditory steady-state responses (ASSRs). Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 122, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.P.; Bobilev, A.M.; Hayrynen, L.K.; Hudgens-Haney, M.E.; Oliver, W.T.; Parker, D.A.; McDowell, J.E.; Buckley, P.A.; Clementz, B.A. Stimulus train duration but not attention moderates γ-band entrainment abnormalities in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 165, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Weisz, N. Auditory cortical generators of the Frequency Following Response are modulated by intermodal attention. NeuroImage 2019, 203, 116185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, A.T. Neuroimaging evidence for Top-Down maturation of selective auditory attention. Brain Topogr. 2011, 24, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.; Purcell, D.W.; Carlyon, R.P.; Gockel, H.E.; Johnsrude, I.S. Attentional modulation of Envelope-Following responses at lower (93–109 Hz) but not higher (217–233 Hz) modulation rates. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2017, 19, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitel, C.; Schröger, E.; Saupe, K.; Müller, M.M. Sustained selective intermodal attention modulates processing of language-like stimuli. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 213, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitel, C.; Maess, B.; Schröger, E.; Müller, M.M. Early visual and auditory processing rely on modality-specific attentional resources. NeuroImage 2013, 70, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, Y.; Davis, C.; Kim, J. Attentional modulation of auditory Steady-State responses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manting, C.L.; Andersen, L.M.; Gulyas, B.; Ullén, F.; Lundqvist, D. Attentional modulation of the auditory steady-state response across the cortex. NeuroImage 2020, 217, 116930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manting, C.L.; Gulyas, B.; Ullén, F.; Lundqvist, D. Auditory steady-state responses during and after a stimulus: Cortical sources, and the influence of attention and musicality. NeuroImage 2021, 233, 117962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manting, C.L.; Gulyas, B.; Ullén, F.; Lundqvist, D. Steady-state responses to concurrent melodies: Source distribution, top-down, and bottom-up attention. Cereb. Cortex 2022, 33, 3053–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Schlee, W.; Hartmann, T.; Lorenz, I.; Weisz, N. Top-down modulation of the auditory steady-state response in a task-switch paradigm. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, H.; Stracke, H.; Bermudez, P.; Pantev, C. Sound Processing Hierarchy within Human Auditory Cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.T.; Bruce, I.C.; Bosnyak, D.J.; Thompson, D.C.; Roberts, L.E. Modulation of Electrocortical Brain Activity by Attention in Individuals with and without Tinnitus. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 127824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riels, K.M.; Rocha, H.A.; Keil, A. No intermodal interference effects of threatening information during concurrent audiovisual stimulation. Neuropsychologia 2020, 136, 107283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.E.; Bosnyak, D.J.; Thompson, D.C. Neural plasticity expressed in central auditory structures with and without tinnitus. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstroh, B.; Müller, M.; Heinz, A.; Wagner, M.; Berg, P.; Elbert, T. Modulation of auditory responses during oddball tasks. Biol. Psychol. 1996, 43, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbaugh, J.W.; Varner, J.L.; Paige, S.R.; Eckardt, M.J.; Ellingson, R.J. Event-related perturbations in an electrophysiological measure of auditory function: A measure of sensitivity during orienting? Biol. Psychol. 1989, 29, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrbaugh, J.W.; Varner, J.L.; Paige, S.R.; Eckardt, M.J.; Ellingson, R.J. Auditory and visual event-related perturbations in the 40 Hz auditory steady-state response. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990, 76, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbaugh, J.W.; Varner, J.L.; Paige, S.R.; Eckardt, M.J.; Ellingson, R.J. Event-related perturbations in an electrophysiological measure of auditory sensitivity: Effects of probability, intensity and repeated sessions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1990, 10, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, B.; Picton, T.W.; Herdman, A.T.; Pantev, C. The effect of attention on the auditory steady-state response. PubMed 2004, 2004, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, C.; Gupta, C.N.; Plis, S.M.; Damaraju, E.; Khullar, S.; Calhoun, V.D.; Bridwell, D.A. The influence of visuospatial attention on unattended auditory 40 Hz responses. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saupe, K.; Widmann, A.; Bendixen, A.; Müller, M.M.; Schröger, E. Effects of intermodal attention on the auditory steady-state response and the event-related potential. Psychophysiology 2009, 46, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saupe, K.; Schröger, E.; Andersen, S.K.; Müller, M.M. Neural mechanisms of intermodal sustained selective attention with concurrently presented auditory and visual stimuli. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saupe, K.; Widmann, A.; Trujillo-Barreto, N.J.; Schröger, E. Sensorial suppression of self-generated sounds and its dependence on attention. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 90, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szychowska, M.; Wiens, S. Visual load does not decrease the auditory steady-state response to 40-Hz amplitude-modulated tones. Psychophysiology 2020, 57, e13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szychowska, M.; Wiens, S. Visual load effects on the auditory steady-state responses to 20-, 40-, and 80-Hz amplitude-modulated tones. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 228, 113240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Ross, B.; Kuriki, S.; Harashima, T.; Obuchi, C.; Okamoto, H. Neurophysiological evaluation of Right-Ear advantage during dichotic listening. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, L.; Bharadwaj, H.M.; Shinn-Cunningham, B.G. Evidence against attentional state modulating scalp-recorded auditory brainstem steady-state responses. Brain Res. 2015, 1626, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicikas, A.; Niciute, I.; Ruksenas, O.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. Effect of attention on 40 Hz auditory steady-state response depends on the stimulation type: Flutter amplitude modulated tones versus clicks. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 629, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, N.; Lecaignard, F.; Müller, N.; Bertrand, O. The modulatory influence of a predictive cue on the auditory steady-state response. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 33, 1417–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekindt, A.; Kaiser, J.; Abel, C. Attentional modulation of the inner ear: A combined otoacoustic emission and EEG study. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 9995–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagura, H.; Tanaka, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Watanabe, H.; Motomura, S.; Sudoh, K.; Nakamura, S. Selective attention measurement of experienced simultaneous interpreters using EEG Phase-Locked response. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 581525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, Y.; Naruse, Y. Phase coherence of auditory steady-state response reflects the amount of cognitive workload in a modified N-back task. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 100, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Miyamoto, A.; Naruse, Y. Estimation of Human Workload from the Auditory Steady-State Response Recorded via a Wearable Electroencephalography System during Walking. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Gong, Q. Background Suppression and its Relation to Foreground Processing of Speech Versus Non-speech Streams. Neuroscience 2018, 373, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruhara, A.; Hayashi, S.; Arake, M.; Yokota, Y.; Naruse, Y.; Hashimoto, A. P-11 Estimation of pilot proficiency during simulator trainings: An auditory steady-state response study. Ningen Kōgaku/Ningen Kougaku 2017, 53 (Suppl. S2), S720–S721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeig, S.; Müller, M.M.; Rockstroh, B. Effects of voluntary movements on early auditory brain responses. Exp. Brain Res. 1996, 110, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Syn. Meth. 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | Sample Size (Age, Males) | Tasks/Conditions | Stimuli (Frequency; Type; Stimuli Presentation) | ASSR Measures and Site | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albrecht et al., 2013 [16] | Healthy: 44 (19–48 years; 26 males) | Counting targets (20%, 20 Hz, or 40 Hz) | 20/40 Hz click trains | EEG, 32 channels; Power and PLI (FCz) | PLI and power increased with attention for both 20 Hz and 40 Hz ASSR |

| Alegre et al., 2008 [31] | Healthy: 12 (27.6 years; 8 males) | (1) Attend to the sound; (2) Read a novel | 1–120 Hz, 1200 Hz AM chirps; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 64 channels; PLI and power. (all channels, Fz) | Power decreased with distraction in the range of 80–120 Hz |

| Bharadwaj et al., 2014 [34] | Healthy: 10 (20–40 years; 8 males) | (1) Count the vowel (letter E); attention to the left or the right stream (signified with visual cues); (2) Ignore sounds and count the visual dot flickers | 35 Hz and 45 Hz AM vowels in different streams; dichotic stimuli presentation | MEG, 306 channels; PLI (whole-brain) and power (20 strongest sources in each auditory ROI) | Power and PLI of 35 or 45 Hz ASSR increased with attention in contralateral auditory cortical areas |

| Coffman et al., 2022 [35] | Healthy: 32 (24.7 years; 22 males) Schizophrenia: 25 (23.3 years; 15 males) | (1) Count auditory stimuli; button press on every 7th stimulus; (2) Ignore the stimuli and watch a video | 40 Hz click trains; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 61 channels; Evoked power and PLI (F1, Fz, F2, FC1, FCz, FC2) | Power and PLI of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention in healthy but not in SZ patients |

| De Jong et al., 2010 [36] | Healthy: 10 (21.1 years; 3 males) (9 reported) | (1) Detect visual (increase or decrease in the main brightness of the 24 Hz flicker) or/and auditory (increase or decrease in the mean loudness of the 40 Hz AM tone) target. Target probability—50%/50%; (2) Discriminate auditory and visual targets, indicate direction of change in volume or brightness. Five attention conditions for each task: Focused attention—100% auditory or 100% visual; divided attention—20%/80%, 50%/50%, 80%/20% of auditory/visual; button press | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM through loudspeaker | EEG, 70 channels; Mean amplitude (4 frontocentral electrodes with maximum amplitude and O9, Iz O10) | No significant effects |

| Gander et al., 2007 [37] | Healthy: 63 (20.6 years; 18 males) | For 31 subjects: (1) Passive listening with video; (2) Detect targets (amplitude change > 400 ms; 50/50%) in S1/S2 pair; button press; For 17 subjects: Passive listening with video; For 15 subjects: (1) Passive listening with video; (2) Passive listening without video | 40.96 Hz; 2000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 128 channels; Amplitude, phase and dipole orientation, 3D dipole location (Fz) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention. No effects for phase, dipole orientation, and dipole 3D location |

| Gander et al., 2010a [38] | Exp 1: Healthy: 63 (20.6 years; 18 males) | For 31 subjects: (1) Detect targets (amplitude change; one of the 78 AM pulses was the target); button press; (2) Passive listening with video; (3) Passive listening without video; For 17 subjects: Passive listening without video; For 15 subjects: Passive listening with video | 40.96 Hz, 2000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 128 channels; Amplitude, phase, dipole moments (Fz), 3D location, total field power (all channels) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention. No effect for phase, dipole orientation, and 3D location |

| Exp 2: Healthy: 18 (21.9 years; 8 males) | (1) Detect targets (amplitude change; 2/3 of stimuli contained a single amplitude enhanced 40 Hz pulse); button press; (2) Passive listening | 40.96 Hz; 2000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 128 channels; Amplitude and phase, dipole orientation, 3D dipole location (Fz) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention. No effect for phase, dipole orientation, and 3D location | |

| Gander et al., 2010b [39] | Exp 1: Healthy: 34 (21.2 years; 14 males); divided into groups: 21 subjects in ‘1 s’ group, 13 in ‘2 min’ group | Simultaneous visual (16 Hz) and auditory streams. (1) Response to visual target (increase in the intensity); mouse click/button press; (2) Response to auditory target (increase in the intensity); mouse click/button press; (3) Passive condition (maintain focus on the fixation cross) | 40.96 Hz, 2000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 128 channels; Amplitude, phase, dipole power (FCz) | Amplitude and dipole power of 40 Hz ASSR increased when attention was required for 1 s to corresponding modality but not for 2 min intervals. No effects for phase |

| Exp 2: Healthy: 39 (22.0 years; 17 males); divided into groups: 15 subjects in ‘1 s’ group, 24 in ‘2 min’ group | Simultaneous auditory streams. (1) Detect targets (increase in the amplitude); mouse click/button press; (2) Passive condition (maintain focus on the fixation cross) | 40.96 Hz and 36.57 Hz simultaneously, 250 and 4100 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | No significant effects | ||

| Griskova-Bulanova et al., 2011 [40] | Healthy: 11 (22.8 years; 6 males) | (1) Count 20 Hz stimuli, (2) Count 40 Hz stimuli; (3) Eyes closed; (4) Eyes open; (5) Read; (6) Visual search-task | 20/40 Hz click trains; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 32 channels;PLI, evoked amplitude, total intensity (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz and P4) | PLI and amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR decreased with distraction tasks compared to closed eyes condition. No effect for total intensity of 40 Hz ASSR |

| Griskova-Bulanova et al., 2018 [32] | Healthy: 27 (23.2 years; 27 males) | (1) Count stimuli; (2) Read; (3) Eyes closed | 40 Hz click trains; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 64 channels; Global field synchronization (all channels) | GFS of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention and closed eyes. GFS of 40 Hz ASSR decreased with distraction |

| Hamm et al., 2015 [41] | Healthy: 18 (40.8 years; 11 males); Schizophrenia: 18 (45.6 years; 9 males) | (1) Detect targets (10%, unmodulated tones); button press; (2) Passive listening | 40 Hz, 500/1000/2000 Hz AM;binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 211 channels; Power (all channels) | No significant effects |

| Hartmann et al., 2019 [42] | Healthy: 38 (mean 24.4 years; 19 males) (34 reported, 24.4 years; 15 males) | Detect deviant auditory or visual stimuli; button press | 114 Hz, /da/sound; | MEG, 306 channels); Power (102 magnetometers) | Power of 114 Hz ASSR increased with attention to the auditory domain |

| Herdman 2011 [43] | Healthy: 13 adults (22 years; 6 males) (10 reported, 5 males) | Attend to relevant deviant (175 ms)/standard (500 ms) 1200 Hz AM tones and detect targets (10%, 1200 Hz, 175 ms); button press. Ignore irrelevant deviant (175 ms)/standard (500 ms) 800 Hz AM | 40 Hz, 800/1200 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | MEG; 151 channels; Amplitude | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Holmes et al., 2017 [44] | Healthy: 30 (24 reported, 20.5 years; 12 males) | (1) Detect deviant stimulus within the attended stream (low-, high-frequency); button press; (2) Attend to visual stimuli and ignore auditory | 93/99/109 Hz, 1027/1343/2913 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG (Cz); EFR phase coherence, SNR, amplitude | Amplitude, phase coherence, and SNR of 93 Hz and 109 Hz ASSR increased with attention to tone stream |

| Keitel et al., 2011 [45] | Healthy: 16 (13 reported, 24.6 years; 6 males) | Perform auditory or visual lexical decision task (words 50%); button press | 40 Hz AM multi-speech babble; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG. 64 channels; Maximum amplitude (Fz, FCz, F1, F2, FC1, FC2) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention to the auditory stream |

| Keitel et al., 2013 [46] | Healthy: 18 (16 reported, 26 years; 10 males) | Perform auditory or visual lexical decision task (words 50%); button press | 40 Hz AM multi-speech babble; binaural stimuli presentation | MEG and EEG, 306 and 60 channels; Amplitude (EEG—T7, T9, TP7, FT7, C5 T8, T10, TP8, FT8, C6; MEG—lateral temporal sites) | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR decreased when attention was shifted from audition to vision for EEG data but not MEG |

| Lazzouni et al., 2010 [29] | Healthy: 15 (26 years; 7 males) | Detect targets (10%, 950 Hz AM); button press | 39 Hz, 1000 Hz AM to the right ear; 41 Hz, 1000 Hz AM to the left ear; monoaural/dichotic stimuli presentation | MEG, 275 channels; Amplitude (left/right temporal areas) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased in the right hemisphere with attention (at the onset of carrier change during dichotic stimuli presentation) |

| Linden et al., 1987 [27] | Exp 1 Healthy: 8 (27–40 years; 6 males) | (1) Read; (2) Count targets (intensity increments) | 40 Hz; 500 Hz AM; monoaural stimuli presentation | EEG, Cz; Amplitude, phase | No significant effects |

| Exp 2 Healthy: 10 (22–38 years; 5 males) | (1) Read; (2) Count targets (AM change from 500 Hz to 535 Hz, and from 1000 Hz to 1050 Hz) | 37 Hz to one ear, 41 Hz to the other; 500/1000 Hz AM; dichotic stimuli presentation | EEG; Fz, Cz, Pz; Amplitude, phase | No significant effects | |

| Mahajan et al., 2014 [47] | Healthy: 23 (22–35 years; 13 males) | Detect target in a cued ear (15% congruent, 15% incongruent; for 16/23.5 Hz changed to 40 Hz; for 32.5/40 Hz changed to 12.5 Hz); button press | 16/23.5 Hz and 32.5/40 Hz; white noise AM; dichotic stimuli presentation | EEG, 64 channels; Power (T7, T8) | No significant effects for 32.5/40 ASSR |

| Manting et al., 2020 [48] | Healthy: 29 (27 reported, 28.6 years; 18 males) | Listen to three melody streams of different pitches, attend to lowest (39 Hz) or highest (43 Hz); report the latest pitch direction; button press | 43 Hz, 196–329 Hz AM; 41 Hz, 147–294 Hz AM; 39 Hz, 131–220 Hz AM; diotic stimuli presentation | MEG; 306 channels; Power; ERF amplitude (all gradiometer sensors) | Power and ERF amplitude of 39 Hz and 43 Hz increased with attention to corresponding frequency |

| Manting et al., 2021 [49] | Healthy: 29 (28.6 years; 20 males) (27 reported) | Listen to three melody streams of different pitches, attend to lowest (39 Hz) or highest (43 Hz); report the latest pitch direction; button press | 43 Hz AM 329–523 Hz; 41 Hz AM 175–349 Hz; 39 Hz AM, 131–220 Hz; diotic stimuli presentation | MEG; 306 channels; Power (all gradiometer sensors) | Power of 39 Hz and 43 Hz ASSR increased with attention to corresponding frequency when the stimulus was present |

| Manting et al., 2022 [50] | Healthy: 28 (28.6 years; 19 males) (25 reported) | Listen to two overlapping melody streams of different pitches, attend to low (39 Hz) or high (43 Hz); report the latest pitch direction; button press | 43 Hz, 329–523 Hz AM; 39 Hz, 131–220 Hz AM; diotic stimuli presentation | MEG; 306 channels; Power (all sensors) | Power of 39 Hz and 43 Hz increased with attention to corresponding frequency |

| Müller et al., 2009 [51] | Healthy:15 (25 years; 9 males) (13 reported) | Detect target in a cued ear (10%, amplitude modulation changes to 12.5/25 Hz); button press | 20 Hz to one ear and 45 Hz to another ear 655 Hz AM; dichotic stimuli presentation | MEG, 148 channels; Power (left/right temporal sources) | No significant effects for 45 Hz ASSR |

| Okamoto et al., 2011 [52] | Healthy: 16 (26.2 years; 8 males) | (1) Detect auditory targets (10%, shift in carrier frequency) presented simultaneously with 8000 Hz white noise of different power (2) Ignore auditory stimulation presented simultaneously with 8000 Hz white noise of different power and detect visual targets; button press | 40 Hz, 1000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | MEG, 275 channels; Source strength | Source strength of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention and decreased with loud masking noises |

| Paul et al., 2014 [53] | Healthy/tinnitus: 30/30 Healthy: (16 reported, 64 years; 5 males and 11 reported, 53.9 years, 8 males); Tinnitus: 17 reported, 62.0 years; 10 males and 11 reported, 48.6 years, 7 males) | (1) Detect targets (~50%, amplitude-enhanced pulse); button press; (2) Passive listening (ignore stimulation) | 40.96 Hz, 500 and 5000 Hz AM binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 128 channels; Total field power (all electrodes) | Total field power of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Pipinis et al., 2018 [30] | Healthy: 20 (21.8 years; 20 males) | (1) Read; (2) Count stimuli | 1–120 Hz/120–1 Hz, 440 Hz AM chirps; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 64 channels; PLI and evoked amplitude (Fz, FCz, Cz) | No significant effects |

| Riels et al., 2020 [54] | Healthy 30 (mean 19 years; 7 males) | Exp 1. Detect transient tone amplitude reduction during rapid serial visual presentation of emotional images; button press | 40.8 Hz, 600 Hz AM; through speakers | EEG; 129 channels; Amplitude, SNR (12 central and frontal channels) | No significant effects |

| Exp 2. Passive viewing and listening task with anticipation of aversive white noise burst | No significant effects | ||||

| Roberts et al., 2012 [55] | Healthy/tinnitus: 12/12 (Healthy: 11 reported, 53.9 years; 6 males; Tinnitus: 11 reported, 48.6 years; 7 males) | (1) Detect targets (66%, pulse of increased amplitude); button press (2) Passive listening | 40.96 Hz; 5000 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 128 channels; Total field power, phase, amplitude (all channels) | Amplitude of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention. No effect on phase |

| Rockstroh et al., 1996 [56] | Exp 1 Healthy: 45 (22.2 years; 45 males) (37 reported) | Detect targets (shift to 500 Hz AM or 2000 Hz AM, 30%); button press | 40 Hz; 1000 Hz AM; monoaural stimuli presentation to the right ear | EEG; Fz, Cz, Pz; Amplitude | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR decreased after frequency shift; at 350–400 ms more after shift to target. Amplitude recovery more pronounced after shift to standard |

| Exp 2 Healthy: 10 (26.3 years; 5 males) (8 reported) | (1) Detect targets (shift to 500 Hz AM, 30%, for two subjects target was 2000 Hz AM in further sessions) button press; (2) Count targets | 41 Hz; 1000 Hz AM; monoaural stimuli presentation to the right ear | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR decreased to targets with active response; no effect with passive counting | ||

| Rohrbaugh et al., 1989 [57] | Healthy: 6 (27 years; 1 male) | (1) Count targets: easy (±200 Hz)/hard (±20 Hz); (2) Passive listening (80 tone bursts of 400 Hz or 600 Hz) | Background: 41 Hz pips, 1000 Hz AM; Foreground: 400 to 600 Hz tone bursts; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; ASSR recording site −2 cm anterior from Cz; ERP (Fz, Cz, Pz); Peak-by-peak latency, amplitude | Latency reduction after the foreground stimulus in hard condition compared to passive. No effects for amplitude |

| Rohrbaugh et al., 1990a [58] | Healthy: 4 (23–28 years; 3 males) | (1) Count auditory targets: easy (±200 Hz)/difficult (±20 Hz); (2) Count visual targets: easy (standard circle and elongated 20° ellipse discrimination)/difficult (standard circle and elongated 60° ellipse discrimination) | Background: 39/41/45 Hz, pips, 1000 Hz AM; Foreground: 400 to 600 Hz tone bursts; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; ASSR recording site −2 cm anterior from Cz; ERP from (Fz, Cz, Pz); Latency, peak-to-peak amplitude | Latencies and amplitude decreased within 200–300 ms after the auditory foreground stimulus |

| Rohrbaugh et al., 1990b [59] | Healthy: 4 (21–27 years; 2 males) | Count targets (30%): loud tone/soft tone | Background: 41 Hz pips, 1000 Hz AM; Foreground: 400 Hz tone bursts; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 2 cm anterior from Cz; Latency, peak-to-peak amplitude | Latency reduction after the foreground stimulus. No effect for amplitude |

| Ross et al., 2004 [60] | Healthy: 12 (23–54 years; 7 males) | (1) Discriminate target (10%, 30 Hz), button press; (2) Count visual stimuli, ignore sound | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM; monoaural stimuli presentation to the right ear | MEG; 151 channels; Dipole moment amplitude | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention, mostly in the left hemisphere |

| Roth et al., 2013 [61] | Healthy: 9 (21–40 years; 9 males) (8 reported) | (1) Play Tetris (easy/difficult levels); (2) Fixate on Tetris (keyboard disabled) while attending to the auditory stimuli (subtle variations in amplitude) | 40 Hz; click trains; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 8 channels (F3, Fz, F4, Cz, P3, P4, O1, O2); Amplitude; SNR (channel with largest SNR) | SNR of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention, and decreased with visuospatial task difficulty |

| Saupe et al., 2009a [62] | Healthy: 15 (7 males) (12 reported, 27.2 years; 7 males) | (1) Detect auditory target (30 Hz; 5 targets and 43 standards); button press; (2) Detect visual target (fixation cross change; 13 times); button press | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 32 channels; Amplitude (Fz, FC1, FC2) | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Saupe et al., 2009b [63] | Healthy: 17 (9 males) (14 reported, 25.5 years, 8 males) | (1) Detect auditory target (30 Hz; 50%); (2) Detect visual target (letter, 50%) | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 64 channels; Amplitude (two adjacent frontocentral electrodes with the largest amplitude) | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Saupe et al., 2013 [64] | Healthy: 15 (19–30 years; 23.5 years; 5 males) | (1) Active listening (press a button when stimulus onset asynchronies were <1.8 s or >5 s long); (2) Passive listening; (3) Self-generation (press a button to start stimuli); (4) Motor-control (no tone generated by button press) | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 61 channels; Amplitude (Fz, FCz, F1, F2, FC1, FC2) | Amplitudes of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Skosnik et al., 2007 [28] | Healthy: 15 (n/a; 5 males) | Count targets (20%, 20/40 Hz, counterbalanced) | 20/40 Hz; click trains, binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 12 channels; Power (F7, F8, Fz, C3, C4, Cz), PLF (Cz) | Power and PLF to 40 Hz increased with attention |

| Szychowska and Wiens 2020a [65] | Exp 1. Healthy: 43 (25.7 years; 20 males) | Respond to visual features of a cross (targets 20%): (1) low load—respond to red cross; (2) high load—respond to upright yellow and inverted green crosses; button press | 40.96 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 6 channels; Amplitude and PLI (Fz, FCz) | No significant effects |

| Exp 2. Healthy: 45 (27.2 years; 21 males) | Respond to visual features of the letters (48 targets of 360) while ignoring the tone: (1) no-load (passive viewing); (2) low-load (color); (3) high load (color-name combinations); (4) very high load (combinations of name, color, and capitalization); button press | 40.96 Hz, 500 Hz AM;binaural stimuli presentation | No significant effects | ||

| Szychowska and Wiens 2020b [66] | Healthy: 33 (27.09 years; 13 male) | Respond to visual features of the letters (48 targets of 247) while ignoring the tone: (1) no-load (passive viewing); (2) low-load (color); (3) high load (color-name combinations); button press | 20.48/40.96/81.92 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 6 channels; Amplitude and PLI (Fz, FCz) | No significant effects |

| Tanaka et al., 2021 [67] | Healthy: 18 (22.9 years; 18 male) | (1) Write down heard AM two-syllable words: to left, right, or both ears; (2) passive listening and watching a silent movie | 35 and 45 Hz AM two-syllable words; diotic/dichotic stimuli presentation | MEG; 204 channels; Amplitude | Amplitude of 35 Hz and 45 Hz ASSRs increased with attention |

| Varghese et al., 2017 [68] | Exp 1. Healthy: 10 (18–28 years; 4 males) (9 reported) | Listen to streams of spoken digits and respond whenever two consecutive, increasing digits were heard in the attended ear (1) during monaural presentation; (2) while ignoring digits presented to the other ear in a dichotic listening; button press | 97/113 Hz, click trains (vocoding) monaural/dichotic stimuli presentation | EEG, 32 channels; PLV (20 channels = 14 channels in common among all subjects + 6 random for each) | No significant effects |

| Exp 2. Healthy: 13 (20–29 years; 3 males) (12 reported) | Attend to (1) a monaural digit stream; (2) to one stream in a dichotic listening; (3) to a visual digit stream during a monaural presentation; button press | 97/113 Hz; click trains (vocoding); monaural/dichotic stimuli presentation | No significant effects | ||

| Voicikas et al., 2016 [69] | Healthy: 22 (22.6 years; 22 males) | (1) Count stimuli; (2) Eyes closed; (3) Read | 40 Hz, 440 Hz AM, and click trains, binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 64 channels; PLI, evoked amplitude (Fz, Cz) | PLI, peak PLI, and peak EA of 40 Hz ASSR elicited by click trains increased with attention versus distraction. No effects on ASSR evoked by AM |

| Weisz et al., 2012 [70] | Healthy: 11 (24–38 years; 5 males) | Define which ear stimulus is presented after the cue: informative (75%) or uninformative (50%). Indicate the side on which the target was perceived | 19/42 Hz; 500/1300 or 1300/500 Hz AM; dichotic stimuli presentation | MEG; 275 channels; Power | Power of 42 Hz ASSR decreased in the right primary auditory cortex with the cue to focus on the right ear (target presented to the ipsilateral ear) |

| Wittekindt et al., 2014 [71] | Healthy: 23 (20–39 years; 10 males) | Detect target in cued stream (visual angle or auditory intensity change); button press | 40 Hz; AM tones: f1 and f2 1000–2000 Hz, f2/f1 ratio 1.21; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG; 41 channels; Power (all channels) | Power of 40 Hz ASSR increased with attention |

| Yagura et al., 2021 [72] | Healthy: 22 (0 males); translators 7 experts (56.71 years) and 15 beginners (51.2 years) | (1) Simultaneous translation from Japanese to English; (2) Shadowing Japanese | 40 Hz, click trains and speech sounds | EEG, 29 channels; PLI (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz P4) | PLI of 40 Hz ASSR increased in experts during the translation condition compared to the shadowing condition |

| Yokota and Naruse 2015 [73] | Healthy: 16 (20–23 years; 8 males). | Visual N-back task: 3 levels of difficulty, and no-load | 40 Hz click trains | MEG, 148 channels; Power and PLI, SNR (all channels) | Power and PLI of 40 Hz ASSR decreased with increased task difficulty |

| Yokota et al., 2017 [74] | Healthy: 15 (20–35 years; 7 males). | Visual N-back task: 3 levels of difficulty, and no-load; walking on a treadmill | 40 Hz, 500 Hz AM; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 8 channels; PLI (Fpz, FC3, FCz, FC4, O1, Oz, O2) | PLI of 40 Hz ASSR decreased with increased task difficulty |

| Zhang et al., 2018 [75] | Healthy: 15 (24 years; 9 males) | Detect targets (rising from 122 to 146 Hz; 100 stimuli): (1) in speech blocks target—vowels; (2) in non-speech—complex tones; both presented with or without a background noise (40 Hz AM); button press | 40 Hz, 0.5–4 k Hz AM noise; binaural stimuli presentation | EEG, 60 channels; Amplitude, PLI (F3, FC3, C3, F4, FC4, C4)) | PLI of 40 Hz ASSR decreased with speech and non-speech stimuli in both hemispheres, and amplitude after speech stimuli only on the left, after non-speech in both |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matulyte, G.; Parciauskaite, V.; Bjekic, J.; Pipinis, E.; Griskova-Bulanova, I. Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response and Attention: A Systemic Review. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14090857

Matulyte G, Parciauskaite V, Bjekic J, Pipinis E, Griskova-Bulanova I. Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response and Attention: A Systemic Review. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(9):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14090857

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatulyte, Giedre, Vykinta Parciauskaite, Jovana Bjekic, Evaldas Pipinis, and Inga Griskova-Bulanova. 2024. "Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response and Attention: A Systemic Review" Brain Sciences 14, no. 9: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14090857

APA StyleMatulyte, G., Parciauskaite, V., Bjekic, J., Pipinis, E., & Griskova-Bulanova, I. (2024). Gamma-Band Auditory Steady-State Response and Attention: A Systemic Review. Brain Sciences, 14(9), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14090857