High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Chlorophyll Isolation

2.3. Samples Description

2.4. High-Pressure Processing

2.5. Determination of Carotenoids, Vitamin E, and Chlorophyll

2.5.1. Extraction Procedure

2.5.2. Identification and Quantification of Carotenoids and Chlorophyll

HPLC-DAD

HPLC–MS/MS

2.5.3. Identification and Quantification of Vitamin E

2.5.4. Limits of Detection and Quantification

2.6. Antioxidant Capacity Assays

2.6.1. Extraction Procedure

2.6.2. The α-Tocopherol Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (αTEAC) Assay

2.6.3. Lipophilic Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (L-ORAC) Assay

2.7. In Vitro Digestion Model

2.7.1. Experimental Design

2.7.2. Isolation of Micellar Fraction

2.7.3. Extraction of Carotenoids and Vitamin E

2.7.4. Calculations

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results & Discussion

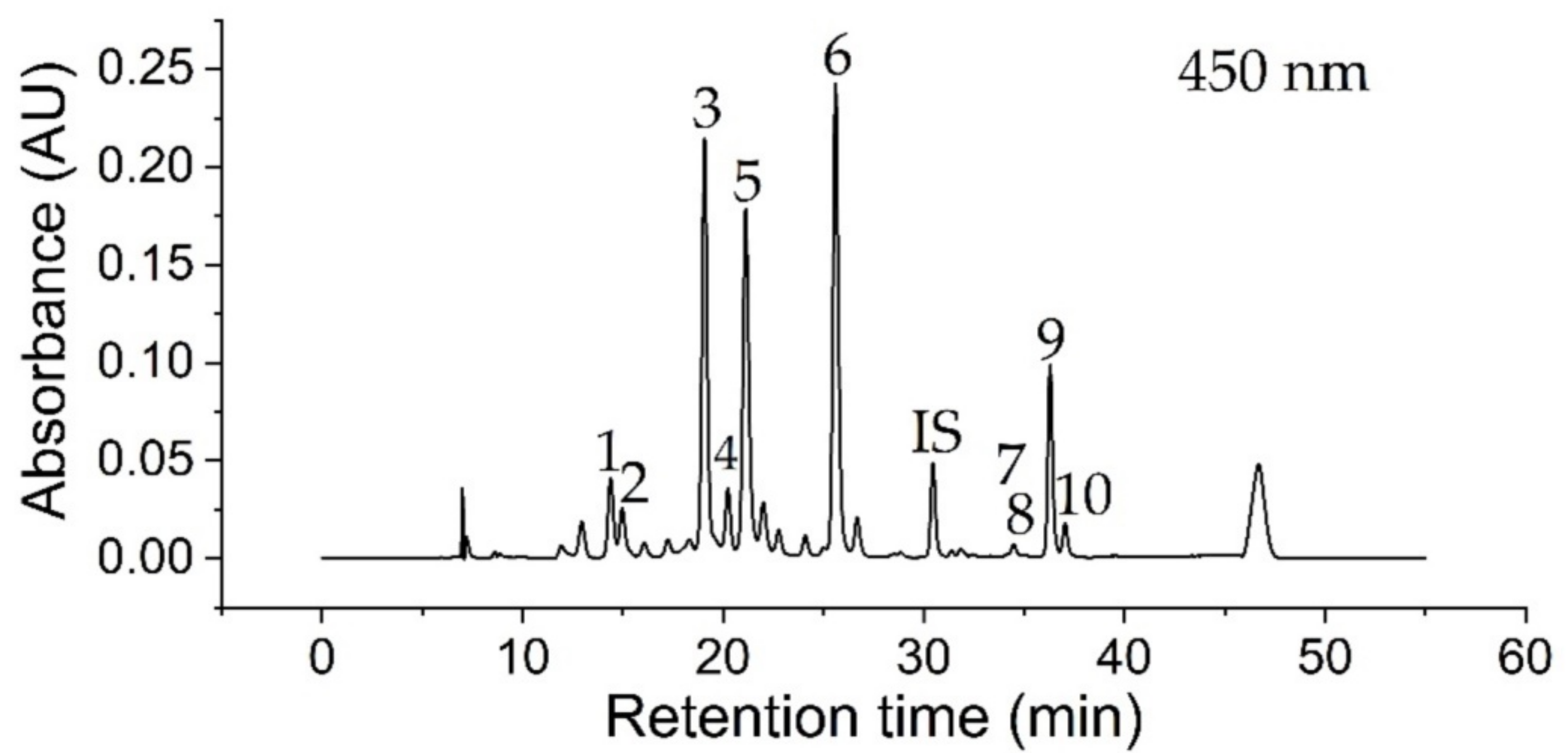

3.1. Identification of Compounds

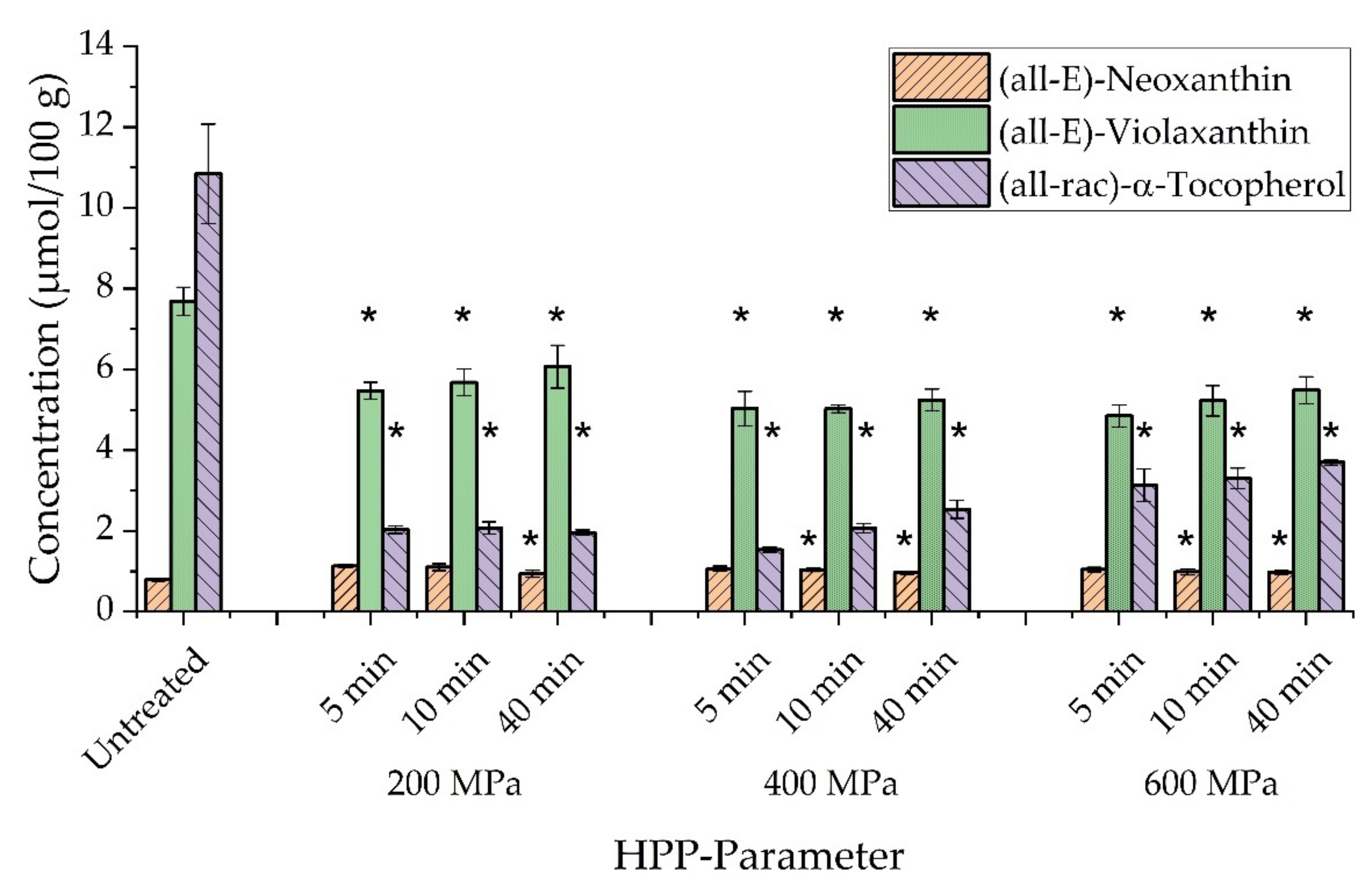

3.2. Extractability

3.3. In Vitro Digestion Assay

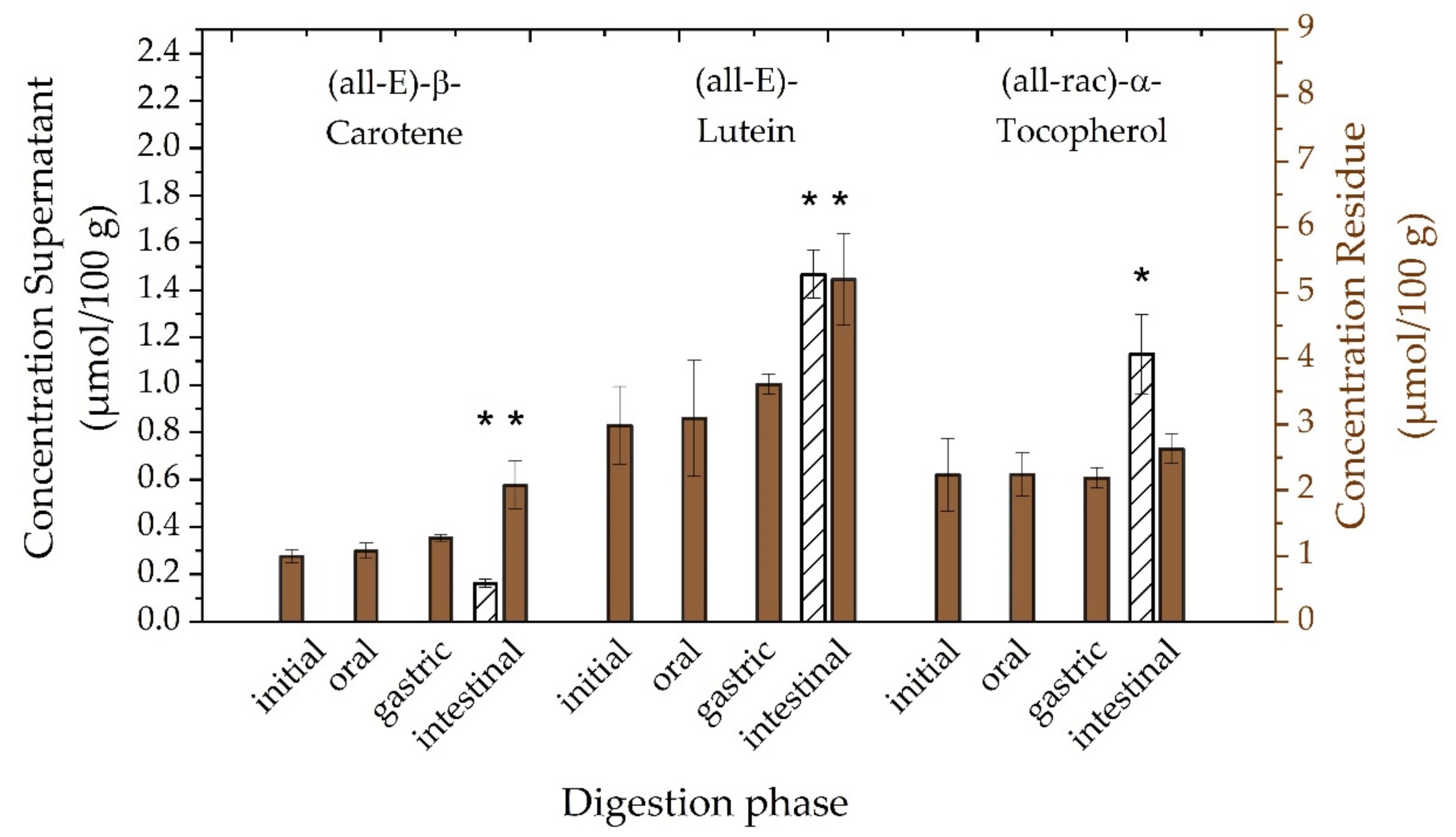

3.3.1. Effect of Oil Volume

3.3.2. Investigation of Digestion Phases

3.3.3. Filtration of Digest

3.3.4. Bioaccessibility

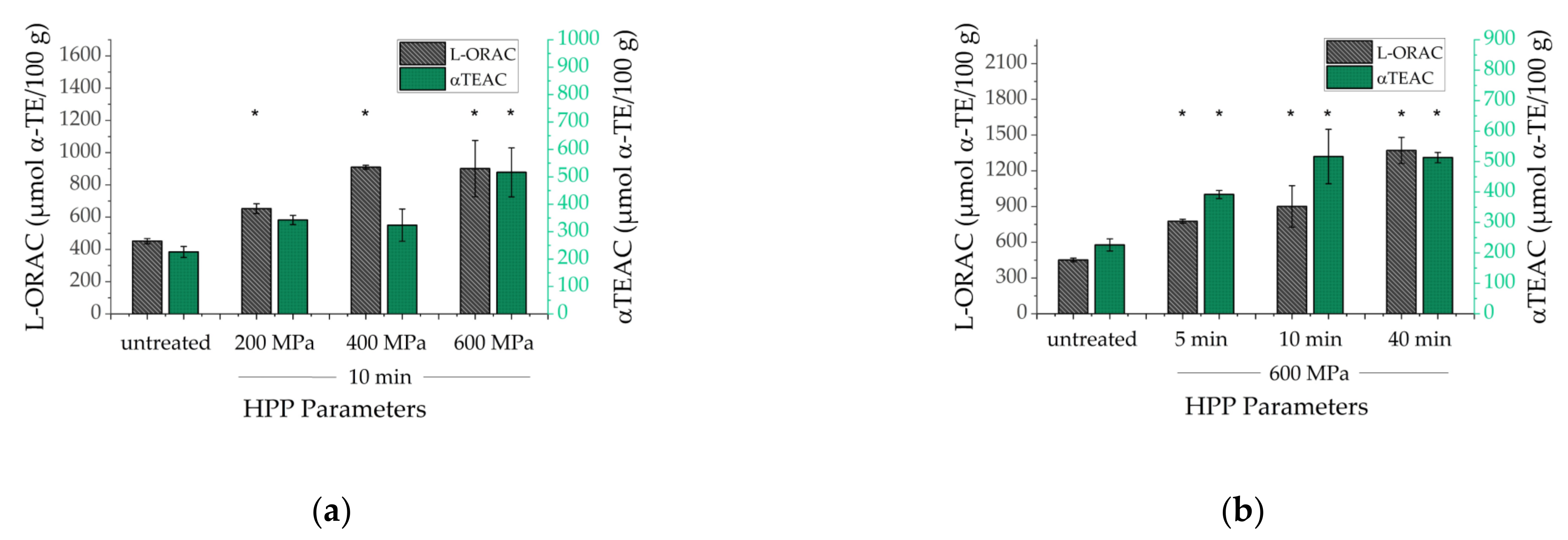

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arenas-Jal, M.; Suñé-Negre, J.M.; Pérez-Lozano, P.; García-Montoya, E. Trends in the food and sports nutrition industry: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2405–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Lefevre, M.; Beecher, G.R.; Gross, M.D.; Keen, C.L.; Etherton, T.D. Bioactive compounds in nutrition and health-research methodologies for establishing biological function: The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids on atherosclerosis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsędek, A. Natural antioxidants and antioxidant capacity of brassica vegetables: A review. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a superfood: Review of the scientific evidence behind the statement. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.S. Nutritional quality and health benefits of vegetables: A review. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 3, 1354–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dias, J.S. Major Classes of phytonutriceuticals in vegetables and health benefits: A review. J. Nutr. Ther. 2012, 1, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, S.; Karwe, M.V. Effect of high-pressure processing on bioactive compounds. In High Pressure Processing of Food; Balasubramaniam, V.M., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Lelieveld, H.L.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 479–507. ISBN 978-1-4939-3233-7. [Google Scholar]

- Knorr, D. Effects of high-hydrostatic-pressure processes on food safety and quality. Food Technol. 1993, 47, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, E.; Martínez, G.; Ceberio, B.; Rodrigo, D.; López, A. High pressure treatment in foods. Foods 2014, 3, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tewari, S.; Sehrawat, R.; Nema, P.K.; Kaur, B.P. Preservation effect of high pressure processing on ascorbic acid of fruits and vegetables: A review. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoukis, P.S.; Panagiotidis, P.; Stoforos, N.G.; Butz, P.; Fister, H.; Tauscher, B. Kinetics of vitamin C degradation under high pressure–moderate temperature processing in model systems and fruit juices. In High Pressure Food Science, Bioscience and Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 310–316. ISBN 978-1-85573-823-2. [Google Scholar]

- Eshtiaghi, M.N.; Knorr, D. Potato cubes response to water blanching and high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Sci. 1993, 58, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, G.B.; Gravina, R.; Paperi, R.; Paoletti, F. Effect of high pressure treatments on peroxidase activity, ascorbic acid content and texture in green peas. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1996, 29, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrén, E.; Diaz, V.; Svanberg, U. Estimation of carotenoid accessibility from carrots determined by an in vitro digestion method. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reboul, E.; Richelle, M.; Perrot, E.; Desmoulins-Malezet, C.; Pirisi, V.; Borel, P. Bioaccessibility of carotenoids and vitamin E from their main dietary sources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8749–8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—An international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulueta, A.; Esteve, M.J.; Frígola, A. ORAC and TEAC assays comparison to measure the antioxidant capacity of food products. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Theile, K.; Böhm, V. In vitro antioxidant activity of tocopherols and tocotrienols and comparison of vitamin E concentration and lipophilic antioxidant capacity in human plasma. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Deemer, E.K. Development and validation of oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay for lipophilic antioxidants using randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin as the solubility enhancer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Oki, T.; Takebayashi, J.; Yamasaki, K.; Takano-Ishikawa, Y.; Hino, A.; Yasui, A. Improvement of the lipophilic-oxygen radical absorbance capacity (L-ORAC) method and single-laboratory validation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Böhm, V. Bioaccessibility of carotenoids and vitamin E from pasta: Evaluation of an in vitro digestion model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, G.; Liaaen-Jensen, S.; Pfander, H. Carotenoids: Handbook; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2004; ISBN 978-3-7643-6180-8. [Google Scholar]

- De Azevedo, C.H.; Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Carotenoid composition of kale as influenced by maturity, season and minimal processing. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefsrud, M.; Kopsell, D.; Wenzel, A.; Sheehan, J. Changes in kale (brassica oleracea l. var. acephala) carotenoid and chlorophyll pigment concentrations during leaf ontogeny. Sci. Hort. 2007, 112, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H. Determination of the carotenoid content in selected vegetables and fruit by HPLC and photodiode array detection. Eur. Food Res. Technol. A 1997, 204, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, C.W.; Popp, M.; Scherz, H.; Bonn, G.K. Development and evaluation of a new method for the determination of the carotenoid content in selected vegetables by HPLC and HPLC-MS-MS. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2000, 38, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.-Y.; Choi, S.R.; Lim, S.-H.; Yeo, Y.; Kweon, S.J.; Bae, Y.-S.; Kim, K.W.; Im, K.-H.; Ahn, S.K.; Ha, S.-H.; et al. Identification and quantification of carotenoids in paprika fruits and cabbage, kale, and lettuce leaves. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2014, 57, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Moreno, A.; Alanís-Garza, P.A.; Mora-Nieves, J.L.; Mora-Mora, J.P.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Kale: An excellent source of vitamin C, pro-vitamin A, lutein and glucosinolates. CyTA J. Food 2014, 12, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilich, A.C.; Tsau, G.J.; Brown, A.; Howard, L.; Klein, B.P.; Jeffery, E.H.; Kushad, M.; Wallig, M.A.; Juvik, J.A. Carotene, tocopherol, and ascorbate contents in subspecies of brassica oleracea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, I.; Van der Plancken, I.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Does high pressure processing influence nutritional aspects of plant based food systems? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Applications and opportunities for pressure-assisted extraction. In High Pressure Processing of Food: Principles, Technology and Applications; Food Engineering Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 173–191. ISBN 978-1-4939-3233-7. [Google Scholar]

- De Ancos, B.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Pilar Cano, M.; Zacarías, L. Effect of high-pressure processing applied as pretreatment on carotenoids, flavonoids and vitamin C in juice of the sweet oranges “Navel” and the red-fleshed “Cara Cara”. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carrión, M.; Vázquez-Gutiérrez, J.L.; Hernando, I.; Quiles, A. Impact of high hydrostatic pressure and pasteurization on the structure and the extractability of bioactive compounds of persimmon “Rojo Brillante”. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C32–C38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, F.; Edge, R.; Land, E.J.; McGarvey, D.J.; Truscott, T.G. Carotenoids enhance vitamin E antioxidant efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Esteve, M.J.; Frigola, A. Impact of high-pressure processing on vitamin E (α-, γ-, and δ-tocopherol), vitamin D (cholecalciferol and ergocalciferol), and fatty acid profiles in liquid foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3763–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silveira, T.F.F.; Cristianini, M.; Kuhnle, G.G.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Filho, J.T.; Godoy, H.T. Anthocyanins, non-anthocyanin phenolics, tocopherols and antioxidant capacity of açaí juice (euterpe oleracea) as affected by high pressure processing and thermal pasteurization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 55, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, A.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. Effects of high pressure processing on bioactive compounds in spinach and rosehip puree. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.; Bickel, H.; Buchholz, B.; Soll, J. Photosynthesis: Proceedings of the fifth International Congress on Photosynthesis, 7–13 September 1980, Halkidiki, Greece; Akoyunoglou, G., Ed.; Balaban International Science Services: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-0-86689-012-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mene-Saffrane, L. Vitamin E biosynthesis and its regulation in plants. Antioxidants 2017, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mokrosnop, V.M. Functions of tocopherols in the cells of plants and other photosynthetic organisms. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2014, 86, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.; Chen, F.; Hu, X. Microstructural and morphological behaviors of asparagus lettuce cells subject to high pressure processing. Food Res. Int. 2015, 71, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, J.K.; Seccafien, C.A.; Stewart, C.M.; Bird, A.R. Effects of high pressure processing on antioxidant activity, and total carotenoid content and availability, in vegetables. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. Carotenoids and chlorophylls in processed xanthophyll-rich food. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Popović, V.; Koutchma, T.; Warriner, K.; Zhu, Y. Effect of thermal, high hydrostatic pressure, and ultraviolet-C processing on the microbial inactivation, vitamins, chlorophyll, antioxidants, enzyme activity, and color of wheatgrass juice. J. Food Process. Eng. 2020, 43, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Baranda, A.B.; Martínez de Marañón, I. The effect of high pressure and high temperature processing on carotenoids and chlorophylls content in some vegetables. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinco, C.M.; Szczepańska, J.; Marszałek, K.; Pinto, C.A.; Inácio, R.S.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Effect of high-pressure processing on carotenoids profile, colour, microbial and enzymatic stability of cloudy carrot juice. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, L.; Van der Plancken, I.; Grauwet, T.; Verlinde, P.; Matser, A.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Thermal versus high pressure processing of carrots: A comparative pilot-scale study on equivalent basis. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeż, M.; Błaszczak, W.; Zielińska, D.; Wiczkowski, W.; Białobrzewski, I. Carotenoids and lipophilic antioxidant capacities of tomato purées as affected by high hydrostatic pressure processing. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Martínez-Monteagudo, S.I.; Cooperstone, J.L.; Riedl, K.M.; Schwartz, S.J.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Impact of thermal and pressure-based technologies on carotenoid retention and quality attributes in tomato juice. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2017, 10, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Jernstedt, J.A.; Slaughter, D.C.; Barrett, D.M. Influence of cell integrity on textural properties of raw, high pressure, and thermally processed onions. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, E409–E416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serment-Moreno, V.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Torres, J.A.; Welti-Chanes, J. Microstructural and physiological changes in plant cell induced by pressure: Their role on the availability and pressure-temperature stability of phytochemicals. Food Eng. Rev. 2017, 9, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; del Cuéllar-Villarreal, M.R.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Ramos-Parra, P.A.; Hernández-Brenes, C. Nonthermal processing technologies as elicitors to induce the biosynthesis and accumulation of nutraceuticals in plant foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 60, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Peng, D.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xie, B.; Sun, Z. Effect of mild high hydrostatic pressure treatments on physiological and physicochemical characteristics and carotenoid biosynthesis in postharvest mango. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 172, 111381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Parra, P.A.; García-Salinas, C.; Rodríguez-López, C.E.; García, N.; García-Rivas, G.; Hernández-Brenes, C.; Díaz de la Garza, R.I. High hydrostatic pressure treatments trigger de novo carotenoid biosynthesis in papaya fruit (carica papaya cv. maradol). Food Chem. 2019, 277, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panozzo, A.; Lemmens, L.; Van Loey, A.; Manzocco, L.; Nicoli, M.C.; Hendrickx, M. Microstructure and bioaccessibility of different carotenoid species as affected by high pressure homogenisation: A case study on differently coloured tomatoes. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 4094–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Rivas, E. Processing Effects on Safety and Quality of Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4200-6115-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chedea, V.S.; Jisaka, M. Lipoxygenase and carotenoids: A co-oxidation story. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 2786–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biacs, P.A.; Daood, H.G. Lipoxygenase-catalysed degradation of carotenoids from tomato in the presence of antioxidant vitamins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2000, 28, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Rao, L.; Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. High pressure processing combined with selected hurdles: Enhancement in the inactivation of vegetative microorganisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1800–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Failla, M.L. Impact of fatty acyl composition and quantity of triglycerides on bioaccessibility of dietary carotenoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8950–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Du, H.; McClements, D.J.; Tang, Z.; Xiao, H. Exploring the effects of carrier oil type on in vitro bioavailability of β-carotene: A cell culture study of carotenoid-enriched nanoemulsions. LWT 2020, 134, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberdi-Cedeño, J.; Ibargoitia, M.L.; Guillén, M.D. Study of the in vitro digestion of olive oil enriched or not with antioxidant phenolic compounds. Relationships between bioaccessibility of main components of different oils and their composition. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría, A.; Garcia-Llatas, G.; Cilla, A. Static digestion models: General introduction. In The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models; Verhoeckx, K., Cotter, P., López-Expósito, I., Kleiveland, C., Lea, T., Mackie, A., Requena, T., Swiatecka, D., Wichers, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-3-319-16104-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tyssandier, V.; Lyan, B.; Borel, P. Main factors governing the transfer of carotenoids from emulsion lipid droplets to micelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2001, 1533, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel, P.; Grolier, P.; Armand, M.; Partier, A.; Lafont, H.; Lairon, D.; Azais-Braesco, V. Carotenoids in biological emulsions: Solubility, surface-to-core distribution, and release from lipid droplets. J. Lipid Res. 1996, 37, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Goñi, I.; Saura-Calixto, F. Determination of β-carotene and lutein available from green leafy vegetables by an in vitro digestion and colonic fermentation method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2936–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, B.; Horton, P.; Pascal, A.A.; Ruban, A.V. Insights into the molecular dynamics of plant light-harvesting proteins in vivo. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado-Lorencio, F.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Herrero-Barbudo, C.; Pérez-Sacristán, B.; Blanco-Navarro, I.; Blázquez-García, S. Comparative in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids from relevant contributors to carotenoid intake. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6387–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulks, R.M.; Southon, S. Challenges to understanding and measuring carotenoid bioavailability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1740, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mène-Saffrané, L.; DellaPenna, D. Biosynthesis, regulation and functions of tocochromanols in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwischer, M.; Porfirova, S.; Bergmüller, E.; Dörmann, P. Alterations in tocopherol cyclase activity in transgenic and mutant plants of arabidopsis affect tocopherol content, tocopherol composition, and oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Courraud, J.; Berger, J.; Cristol, J.-P.; Avallone, S. Stability and bioaccessibility of different forms of carotenoids and vitamin A during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopec, R.E.; Gleize, B.; Borel, P.; Desmarchelier, C.; Caris-Veyrat, C. Are lutein, lycopene, and β-carotene lost through the digestive process? Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, L. Analytical sample preparation: The use of syringe filters. Filtr. Sep. 2009, 46, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortak, M.; Caltinoglu, C.; Sensoy, I.; Karakaya, S.; Mert, B. Changes in functional properties and in vitro bioaccessibilities of β-carotene and lutein after extrusion processing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B.; Kimura, M. HarvestPlus Handbook for Carotenoid Analysis; HarvestPlus Technical Monograph 2; HarvestPlus: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: https://www.harvestplus.org/node/536 (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Eriksen, J.N.; Luu, A.Y.; Dragsted, L.O.; Arrigoni, E. Adaption of an in vitro digestion method to screen carotenoid liberation and in vitro accessibility from differently processed spinach preparations. Food Chem. 2017, 224, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte-Real, J. Bioavailability of Carotenoids—Impact of High Mineral Concentrations (BIOCAR); Technische Universität Kaiserslautern: Kaiserslautern, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C.M. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Components: Effects of Innovative Processing Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-805257-0. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven, C.; Matser, A.M.; van den Berg, R.W. Inactivation of soybean trypsin inhibitors and lipoxygenase by high-pressure processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashurabad, P.C.; Palika, R.; Jyrwa, Y.W.; Bhaskarachary, K.; Pullakhandam, R. Dietary fat composition, food matrix and relative polarity modulate the micellarization and intestinal uptake of carotenoids from vegetables and fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halliwell, B. How to characterize a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1990, 9, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlček, J.; Juríková, T.; Škrovánková, S.; Paličková, M.; Orsavová, J.; Mišurcová, L.; Hlaváčová, I.; Sochor, J.; Sumczynski, D. Polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of fruit and vegetable beverages processed by different technology methods. Potravinarstvo 2016, 10, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Qin, W.; Ma, L.; Xu, F.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y. Effect of high pressure processing and thermal treatment on physicochemical parameters, antioxidant activity and volatile compounds of green asparagus juice. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Marín, E.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Lloría, R.; de Ancos, B.; Cano, M.P. Onion high-pressure processing: Flavonol content and antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, P.; Edenharder, R.; García, A.F.; Fister, H.; Merkel, C.; Tauscher, B. Changes in functional properties of vegetables induced by high pressure treatment. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.-C. Evaluation of processing qualities of tomato juice induced by thermal and pressure processing. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, P.; Fernández García, A.; Lindauer, R.; Dieterich, S.; Bognár, A.; Tauscher, B. Influence of ultra high pressure processing on fruit and vegetable products. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Compound Name | tR (min) | λmax 1 (nm) | λmax 2 (nm) | λmax 3 (nm) | m/z [M + H]+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (all-E)-Violaxanthin | 14.39 | 415.0 | 439.0 | 469.0 | 601.3 1 |

| 2 | (all-E)-Neoxanthin | 14.97 | 413.0 | 436.0 | 465.0 | 601.3 2,4 |

| 3 | (all-E)-Lutein | 19.07 | 422.0 | 445.0 | 473.0 | 569.2 3 |

| 4 | (all-E)-Zeaxanthin | 20.23 | 428.0 | 451.0 | 478.0 | 569.2 |

| 5 | Chlorophyll b | 21.12 | 457.0 | 589.0 | 644.0 | 907.3 |

| 6 | Chlorophyll a | 25.60 | 432.0 | 618.0 | 662.0 | 893.3 |

| 7 | (15Z)-β-Carotene | 34.13 | 339.0 | 449.0 | 474.0 | 537.3 |

| 8 | (13Z)-β-Carotene | 34.46 | 338.0 | 446.0 | 470.0 | 537.3 |

| 9 | (all-E)-β-Carotene | 36.29 | - | 453.0 | 479.0 | 537.3 |

| 10 | (9Z)-β-Carotene | 37.04 | - | 447.0 | 473.0 | 537.3 |

| Compound | Untreated | 200 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min | 400 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min | 600 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration in µmol/100 g | ||||||||||

| (all-E)-β-Carotene | 9.83 ± 0.53 | 9.66 ± 0.69 | 9.36 ± 0.33 | 10.20 ± 0.90 | 8.81 ± 0.52 | 8.53 ± 0.23 | 8.60 ± 0.37 | 8.14 ± 0.16 | 8.73 ± 0.78 | 9.67 ± 0.83 |

| (9Z)-β-Carotene | 1.90 ± 0.15 | 2.11 ± 0.12 | 2.06 ± 0.18 | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 1.73 ± 0.09 | 1.76 ± 0.04 | 1.81 ± 0.08 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 1.85 ± 0.01 | 2.03 ± 0.12 |

| (13Z)-β-Carotene | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | 1.05 ± 0.05 |

| (15Z)-β-Carotene | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.03 * |

| (all-E)-Lutein | 14.51 ± 0.75 | 13.11 ± 0.75 | 14.00 ± 1.06 | 12.49 ± 0.33 | 12.05 ± 0.85 | 11.79 ± 0.25 | 12.09 ± 0.57 | 11.44 ± 0.35 | 12.19 ± 0.84 | 12.64 ± 0.63 |

| (all-E)-Zeaxanthin | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 1.02 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.03 * | 0.96 ± 0.08 * | 0.97 ± 0.12 * | 0.87 ± 0.06 * | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.03 |

| Chlorophyll a | 77.99 ± 5.28 | 64.93 ± 2.04 * | 65.31 ± 2.00 * | 69.62 ± 6.52 | 57.04 ± 1.47 * | 58.87 ± 3.69 * | 61.08 ± 3.51 * | 56.94 ± 2.53 * | 62.14 ± 4.84 * | 63.19 ± 2.81 * |

| Chlorophyll b | 27.78 ± 2.42 | 22.71 ± 0.42 * | 24.44 ± 2.62 | 23.31 ± 0.73 | 20.84 ± 1.43 * | 20.79 ± 0.64 * | 22.02 ± 1.48 * | 19.23 ± 1.46 * | 21.05 ± 1.87 * | 21.60 ± 0.23 * |

| Filter Material | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | CA | MCE | PA | PP | PTFE | PVDF |

| Concentration in Filtered Supernatant (µmol/100 g) | ||||||

| (all-E)-β-Carotene | 0.19 ± 1.5 × 10−5 | 0.20 ± 2.3 × 10−3 | 0.17 ± 7.0 × 10−4 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 7.8 × 10−4 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| (all-E)-Lutein | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 7.6 × 10−4 | 0.44 ± 3.6 × 10−3 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.01 |

| α-Tocopherol | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.02 |

| Compound | Un- treated | 200 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min | 400 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min | 600 MPa 5 min | 10 min | 40 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility in % | ||||||||||

| β-Carotene | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.4 |

| α-Toco- pherol | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 11.3 ± 4.2 | 14.0 ± 5.6 | 14.7 ± 2.9 | 16.7 ± 5.9 | 17.4 ± 3.8 | 20.1 ± 6.2 | 17.9 ± 3.3 | 19.1 ± 4.3 | 21.0 ± 2.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmidt, M.; Hopfhauer, S.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Böhm, V. High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111688

Schmidt M, Hopfhauer S, Schwarzenbolz U, Böhm V. High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants. 2021; 10(11):1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111688

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmidt, Mario, Sofia Hopfhauer, Uwe Schwarzenbolz, and Volker Böhm. 2021. "High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity" Antioxidants 10, no. 11: 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111688

APA StyleSchmidt, M., Hopfhauer, S., Schwarzenbolz, U., & Böhm, V. (2021). High-Pressure Processing of Kale: Effects on the Extractability, In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids & Vitamin E and the Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants, 10(11), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111688