Apitherapy and Periodontal Disease: Insights into In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

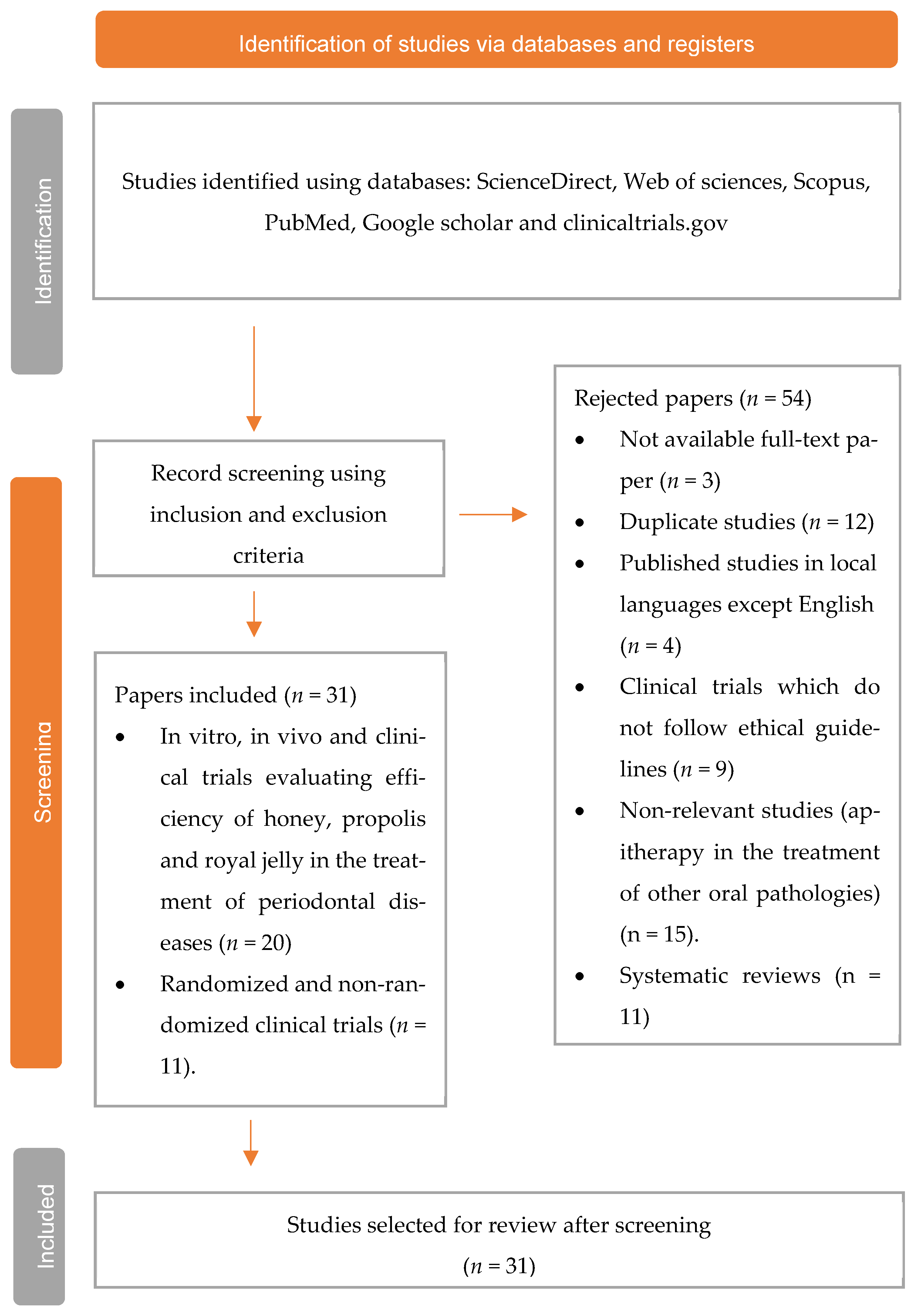

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (i)

- Studies that did not have full text available.

- (ii)

- Clinical trials that do not follow ethical guidelines.

- (iii)

- Published studies in local languages except for English.

- (iv)

- Nonrelevant studies (apitherapy in the treatment of other oral pathologies).

- (v)

- Systematic reviews.

- (i)

- In vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies evaluating the efficiency of honey, propolis, and royal jelly in the treatment of periodontal diseases.

- (ii)

- Findings published in English.

- (iii)

- Findings published within the period from 2016 to 2021.

- (iv)

- Randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Scientific Studies Evaluating Honeybee Products in Periodontal Disease Treatment

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Studies

3.2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.3. Safety of Honeybee Products in Periodontal Disease Treatment

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Prakash, S.; Radha; Kumar, M.; Kumari, N.; Thakur, M.; Rathour, S.; Pundir, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Bangar, S.P.; Dhumal, S.; et al. Plant-Based Antioxidant Extracts and Compounds in the Management of Oral Cancer. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Prakash, S.; Radha; Kumari, N.; Pundir, A.; Punia, S.; Saurabh, V.; Choudhary, P.; Changan, S.; Dhumal, S.; et al. Beneficial role of antioxidant secondary metabolites from medicinal plants in maintaining oral health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasi, M.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, M.; Thapa, S.; Prajapati, U.; Tak, Y.; Changan, S.; Saurabh, V.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, A.; et al. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) bioactives and its role in alleviating oral pathologies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Walczyńska-Dragon, K.; Felitti, R.; Nitecka-Buchta, A.; Baron, S.; Olczyk, P. The Influence of Propolis on Dental Plaque Reduction and the Correlation between Dental Plaque and Severity of COVID-19 Complications-A Literature Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Propolis, Bee Honey, and Their Components Protect against Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review of In Silico, In vitro, and Clinical Studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahallawy, E.K.; Mohamed, Y.; Abdo, W.; El-Gohary, F.A.; Ahmed Awad Ali, S.; Yanai, T. New Insights into Potential Benefits of Bioactive Compounds of Bee Products on COVID-19: A Review and Assessment of Recent Research. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 7, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Valverde, N.; Pardal-Peláez, B.; López-Valverde, A.; Flores-Fraile, J.; Herrero-Hernández, S.; Macedo-De-sousa, B.; Herrero-Payo, J.; Ramírez, J.M. Effectiveness of Propolis in the Treatment of Periodontal Disease: Updated Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madianos, P.N.; Bobetsis, Y.A.; Offenbacher, S. Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) and periodontal disease: Pathogenic mechanisms. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40 (Suppl. S14), S170–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, K.; Wegner, N.; Yucel-Lindberg, T.; Venables, P.J. Periodontitis in RA-the citrullinated enolase connection. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalla, E.; Papapanou, P.N. Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: A tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2011, 7, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebschull, M.; Demmer, R.T.; Papapanou, P.N. “Gum Bug, Leave My Heart Alone!”—Epidemiologic and Mechanistic Evidence Linking Periodontal Infections and Atherosclerosis. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Genco, R.J.; Van Dyke, T.E. Prevention: Reducing the risk of CVD in patients with periodontitis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 479–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darveau, R.P. Periodontitis: A polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, B.M. Antibacterial agents in the control of supragingival plaque--a review. Br. Dent. J. 1999, 186, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.J.; Jeong, H.O.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Joo, J.Y.; Shin, Y.; Kang, J.; Park, A.K.; et al. Prediction of Chronic Periodontitis Severity Using Machine Learning Models Based on Salivary Bacterial Copy Number. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusleme, L.; Dupuy, A.K.; Dutzan, N.; Silva, N.; Burleson, J.A.; Strausbaugh, L.D.; Gamonal, J.; Diaz, P.I. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiao, Y.; Darzi, Y.; Tawaratsumida, K.; Marchesan, J.T.; Hasegawa, M.; Moon, H.; Chen, G.Y.; Núñez, G.; Giannobile, W.V.; Raes, J.; et al. Induction of bone loss by pathobiont-mediated Nod1 signaling in the oral cavity. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Liang, S.; Payne, M.A.; Hashim, A.; Jotwani, R.; Eskan, M.A.; McIntosh, M.L.; Alsam, A.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Lambris, J.D.; et al. A Low-Abundance Biofilm Species Orchestrates Inflammatory Periodontal Disease through the Commensal Microbiota and the Complement Pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Settem, R.P.; El-Hassan, A.T.; Honma, K.; Stafford, G.P.; Sharma, A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia Induce Synergistic Alveolar Bone Loss in a Mouse Periodontitis Model. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orth, R.K.H.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Dashper, S.G.; Reynolds, E.C. Synergistic virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola in a murine periodontitis model. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2011, 26, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikilitas, A.; Karaaslan, F.; Aydin, E.Ö.; Yigit, U.; Ertugrul, A.S. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in subjects with different stages of periodontitis according to the new classification. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2022, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nędzi-Góra, M.; Kowalski, J.; Górska, R. The Immune Response in Periodontal Tissues. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2017, 65, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochalska, M.; Potempa, J. Manipulation of Neutrophils by Porphyromonas gingivalis in the Development of Periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsantikos, E.; Lau, M.; Castelino, C.M.N.; Maxwell, M.J.; Passey, S.L.; Hansen, M.J.; McGregor, N.E.; Sims, N.A.; Steinfort, D.P.; Irving, L.B.; et al. Granulocyte-CSF links destructive inflammation and comorbidities in obstructive lung disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2406–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendyala, G.; Thomas, B.; Kumari, S. The challenge of antioxidants to free radicals in periodontitis. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2008, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, I.; Machado Moreira, E.A.; Filho, D.W.; De Oliveira, T.B.; Da Silva, M.B.S.; Fröde, T.S. Proinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers in Patients with Periodontal Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2007, 2007, 045794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Sulaiman, A.E.; Shehadeh, R.M.H. Assessment of Total Antioxidant Capacity and the Use of Vitamin C in the Treatment of Non-Smokers with Chronic Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Andrukhov, O.; Rausch-Fan, X. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant System in Periodontitis. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ara, S.A.; Ashraf, S.; Arora, V.; Rampure, P. Use of Apitherapy as a Novel Practice in the Management of Oral Diseases: A Review of Literature. J. Contemp. Dent. 2013, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Prakash, S.; Bhatia, R.; Negi, M.; Singh, J.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K. Generation of structurally diverse pectin oligosaccharides having prebiotic attributes. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Radha; Devi, H.; Prakash, S.; Rathore, S.; Thakur, M.; Puri, S.; Pundir, A.; Bangar, S.P.; Changan, S.; et al. Ethnomedicinal plants used in the health care system: Survey of the mid hills of solan district, Himachal Pradesh, India. Plants 2021, 10, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellner, M.; Winter, D.; Von Georgi, R.; Münstedt, K. Apitherapy: Usage and Experience in German Beekeepers. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 5, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Silva, A.S. (Eds.) Nonvitamin and Nonmineral Nutritional Supplements; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Cui, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, B. Comparison of the nutrient composition of royal jelly and worker jelly of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Apidologie 2016, 47, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melliou, E.; Chinou, I. Chemistry and Bioactivities of Royal Jelly. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2014, 43, 261–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Campos, M.G.; Fratini, F.; Altaye, S.Z.; Li, J. New Insights into the Biological and Pharmaceutical Properties of Royal Jelly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bălan, A.; Moga, M.A.; Dima, L.; Toma, S.; Neculau, A.E.; Anastasiu, C.V. Royal Jelly—A traditional and natural remedy for postmenopausal symptoms and aging-related pathologies. Molecules 2020, 25, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Cilia, G.; Mancini, S.; Felicioli, A. Royal Jelly: An ancient remedy with remarkable antibacterial properties. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; Sheikh, B.Y.; Farag, M.A.; Saeed, A.; Larik, F.A.; Koca-Caliskan, U.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Hassan, M.; Wahabi, H.A.; et al. Bee Venom Composition: From Chemistry to Biological Activity. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2019, 60, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, R.; Frangieh, J.; Rima, M.; El Obeid, D.; Sabatier, J.M.; Fajloun, Z. Bee Venom: Overview of Main Compounds and Bioactivities for Therapeutic Interests. Molecules 2019, 24, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fratellone, P.M.; Tsimis, F.; Fratellone, G. Apitherapy products for medicinal use. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuğur-Samanc, A.E.; Kekeçoğlu, M. An evaluation of the chemical content and microbiological contamination of Anatolian bee venom. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Seedi, H.R.; Eid, N.; Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Rateb, M.E.; Afifi, H.S.; Algethami, A.F.; Zhao, C.; Al Naggar, Y.; Alsharif, S.M.; Tahir, H.E.; et al. Honeybee Products: Preclinical and Clinical Studies of Their Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, V.D. Propolis: A Wonder Bees Product and Its Pharmacological Potentials. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toreti, V.C.; Sato, H.H.; Pastore, G.M.; Park, Y.K. Recent progress of propolis for its biological and chemical compositions and its botanical origin. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 697390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.I.; Ullah, A.; Khan, K.A.; Attaullah, M.; Khan, H.; Ali, H.; Bashir, M.A.; Tahir, M.; Ansari, M.J.; Ghramh, H.A.; et al. Composition and functional properties of propolis (bee glue): A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Barboza, A.; Aitken-Saavedra, J.P.; Ferreira, M.L.; Fábio Aranha, A.M.; Lund, R.G. Are propolis extracts potential pharmacological agents in human oral health? -A scoping review and technology prospecting. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 271, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnakady, Y.A.; Rushdi, A.I.; Franke, R.; Abutaha, N.; Ebaid, H.; Baabbad, M.; Omar, M.O.M.; Al Ghamdi, A.A. Characteristics, chemical compositions and biological activities of propolis from Al-Bahah, Saudi Arabia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kocot, J.; Kiełczykowska, M.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Kurzepa, J.; Musik, I. Antioxidant Potential of Propolis, Bee Pollen, and Royal Jelly: Possible Medical Application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7074209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Adham, E.K.; Hassan, A.I.; Dawoud, M.M.A. Evaluating the role of propolis and bee venom on the oxidative stress induced by gamma rays in rats. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, T.; Starowicz, M.; Kłębukowska, L.; Hanus, P. The Profile of Polyphenolic Compounds, Contents of Total Phenolics and Flavonoids, and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Bee Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berretta, A.A.; Silveira, M.A.D.; Cóndor Capcha, J.M.; De Jong, D. Propolis and its potential against SARS-CoV-2 infection mechanisms and COVID-19 disease: Running title: Propolis against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, N.; Sartori, A.A.; Honorio, M.D.S.; Conte, F.L.; Tasca, K.I.; Santiago, K.B.; Sforcin, J.M. Propolis antiviral and immunomodulatory activity: A review and perspectives for COVID-19 treatment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodwad, V.; Kukreja, B. Propolis mouthwash: A new beginning. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2011, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halboub, E.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Al-Wesabi, M.; Al-Kamel, A.; Shamala, A.; Al-Sharani, A.; Koppolu, P. Efficacy of propolis-based mouthwashes on dental plaque and gingival inflammation: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, A. Honeybee propolis extract in periodontal treatment: A clinical and microbiological study of propolis in periodontal treatment. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2012, 23, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Rashid, M.; Tipu, H.N. Propolis, A Hope for the Future in Treating Resistant Periodontal Pathogens. Cureus 2016, 8, e682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshimasu, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Sakai, N.; Yagi, A.; Hirayama, S.; Morinaga, Y.; Furukawa, S.; Nakao, R. Rapid Bactericidal Action of Propolis against Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambur, Z.; Miljkovic-Selimovic, B.; Opacic, D.; Vukovic, B.; Malesevic, A.; Ivancajic, L.; Aleksic, E. Inhibitory effects of propolis and essential oils on oral bacteria. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary George, R.; Kasliwal, A.V. Effectiveness of Propolis, Probiotics and Chlorhexidine on Streptococcus Mutans and Candida Albicans: An In-Vitro Study. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P.A.; Jon, L.Y.; Torres, D.J.; Amaranto, R.E.; Díaz, I.E.; Medina, C.A. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and cytotoxic activities and chemical compositions of Peruvian propolis in an In vitro oral biofilm. F1000Research 2021, 10, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, S.L.F.; Damasceno, J.T.; Faveri, M.; Figueiredo, L.; da Silva, H.D.; de Alencar Alencar, S.M.; Rosalen, P.L.; Feres, M.; Bueno-Silva, B. Brazilian red propolis reduces orange-complex periodontopathogens growing in multispecies biofilms. Biofouling 2019, 35, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Figueiredo, K.A.; Da Silva, H.D.P.; Miranda, S.L.F.; Gonçalves, F.J.D.S.; de Sousa, A.P.; de Figueiredo, L.C.; Feres, M.; Bueno-Silva, B. Brazilian Red Propolis Is as Effective as Amoxicillin in Controlling Red-Complex of Multispecies Subgingival Mature Biofilm In vitro. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stähli, A.; Schröter, H.; Bullitta, S.; Serralutzu, F.; Dore, A.; Nietzsche, S.; Milia, E.; Sculean, A.; Eick, S. In vitro Activity of Propolis on Oral Microorganisms and Biofilms. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, A.B.S.; de Araújo Rodriguez, L.R.N.; Santos, R.K.B.; Marinho, R.R.B.; Abreu, S.; Peixoto, R.F.; de Vasconcelos Gurgel, B.C. Antifungal activity of propolis against Candida species isolated from cases of chronic periodontitis. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Arimatsu, K.; Minagawa, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Sato, K.; Takahashi, N.; Nakajima, T.; Yamazaki, K. Brazilian propolis mitigates impaired glucose and lipid metabolism in experimental periodontitis in mice. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soekanto, S.A.; Safitri, Y.N.; Zeid, H.; Gultom, F.P.; Djais, A.A.; Darwita, R.R.; Sahlan, M. Effectiveness of propolis gel on Mus musculus (Swiss Webster) periodontitis model with ligature silk thread application. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2344, 040008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.-J.; Kang, K.-M.; Lee, K.-H.; Yoo, S.-Y.; Kook, J.-K.; Lee, D.S.; Yu, S.-J. Effect of Garcinia mangostana L. and propolis extracts on the inhibition of inflammation and alveolar bone loss in ligature-induced periodontitis in rats. Int. J. Oral Biol. 2019, 44, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Saleh, Z.; Jalal, J. Effect of local propolis irrigation in experimental periodontitis in rats on inflammatory markers (IL-1β and TNF-α) and oxidative stress. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, D.; Karibasappa, S.N.; Mehta, D.S. Royal Jelly Antimicrobial Activity against Periodontopathic Bacteria. J. Interdiscip. Dent. 2018, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, A.; Gupta, S.J.; Jain, A.; Shetty, D.C.; Sharma, N. Evaluation and comparison of the antimicrobial activity of royal jelly—A holistic healer against periodontopathic bacteria: An In vitro study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2020, 24, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, I.; Das, N.; Ranjan, P.; Sujatha, R.; Gupta, R.; Gupta, N. A Preliminary Study on the Evaluation of In-vitro Inhibition Potential of Antimicrobial Efficacy of Raw and Commercial Honey on Escherichia coli: An Emerging Periodontal Pathogen. Mymensingh Med. J. 2021, 30, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Sun, W.; Wu, T.; Lu, R.; Shi, B. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester attenuates lipopolysaccharide-stimulated proinflammatory responses in human gingival fibroblasts via NF-κB and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 794, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; An, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, W.H.; Gwon, M.G.; Kim, H.J.; Han, S.M.; Park, I.S.; Park, S.C.; Leem, J.; et al. Bee venom attenuates Porphyromonas gingivalis and RANKL-induced bone resorption with osteoclastogenic differentiation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 129, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.H.; An, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Gwon, M.G.; Gu, H.; Park, J.B.; Sung, W.J.; Kwon, Y.C.; Park, K.D.; Han, S.M.; et al. Bee Venom Inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis Lipopolysaccharides-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines through Suppression of NF-κB and AP-1 Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2016, 21, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; An, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Gwon, M.G.; Gu, H.; Jeon, M.; Kim, M.K.; Han, S.M.; Park, K.K. Anti-inflammatory effect of melittin on Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS-stimulated human keratinocytes. Molecules 2018, 23, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakao, R.; Senpuku, H.; Ohnishi, M.; Takai, H.; Ogata, Y. Effect of topical administration of propolis in chronic periodontitis. Odontology 2020, 108, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, S.; Birang, R.; Jamshidian, N. Effect of Propolis mouthwash on clinical periodontal parameters in patients with gingivitis: A double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Serrano, J.; López-Pintor, R.M.; Serrano, J.; Torres, J.; Hernández, G.; Sanz, M. Short-term efficacy of a gel containing propolis extract, nanovitamin C and nanovitamin E on peri-implant mucositis: A double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. J. Periodontal Res. 2021, 56, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, R.; Siddibhavi, M.; Sankeshwari, R.; Patil, P.; Jalihal, S.; Ankola, A. Effectiveness of three mouthwashes—Manuka honey, Raw honey, and Chlorhexidine on plaque and gingival scores of 12–15-year-old school children: A randomized controlled field trial. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2018, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Ko, K.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Oh, J.W.; Lim, H.C.; Lee, D.W.; Choi, S.H.; Cha, J.K. Clinical and Immunological Efficacy of Mangosteen and Propolis Extracted Complex in Patients with Gingivitis: A Multi-Centered Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisbona-González, M.J.; Muñoz-Soto, E.; Lisbona-González, C.; Vallecillo-Rivas, M.; Diaz-Castro, J.; Moreno-Fernandez, J. Effect of Propolis Paste and Mouthwash Formulation on Healing after Teeth Extraction in Periodontal Disease. Plants 2021, 10, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparabombe, S.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Tosco, V.; Orilisi, G.; Hosein, A.; Ferrante, L.; Putignano, A.; Orsini, G. Efficacy of an All-Natural Polyherbal Mouthwash in Patients with Periodontitis: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammarinaro, E.; Marconcini, S.; Genovesi, A.; Poli, G.; Lorenzi, C.; Covani, U. Propolis as an adjuvant to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A clinical study with salivary antioxidant capacity assessment. Minerva Stomatol. 2018, 67, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, S.; Nagarajappa, R.; Ramesh, G.; Bapat, K. Effect of propolis mouth rinse on oral microorganisms—A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 6139–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machorowska-Pieniążek, A.; Morawiec, T.; Olek, M.; Mertas, A.; Aebisher, D.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Advantages of using toothpaste containing propolis and plant oils for gingivitis prevention and oral cavity hygiene in cleft lip/palate patients. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Abtahi, M.; Hasanzadeh, N.; Farahzad, Z.; Noori, M.; Noori, M. Effect of Propolis mouthwash on plaque and gingival indices over fixed orthodontic patients. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bee Products/Country of Origin | Bacterial Strain/Yeast Strain/Cell Line | Obtained Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial studies | |||

| Propolis (Margalla hills, Islamabad) | Prevotella melaninogenica, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Porphyromonas asaccharolytica and Prevotella intermedia | EEP (30% w/v concentration) shows an inhibitory effect on periodontal bacteria with zone of inhibition 18.3 ± 0.64 mm for P. melaninogenica, 18.9 ± 0.05 mm for P. gingivalis, 22.8 ± 0.28 mm for P. asaccharolytica, and 22.8 ± 0.18 mm for P. intermedia. | [62] |

| Propolis (Minas Gerais State, Brazil) | Porphyromonas gingivalis | Result of both assays reported the MIC value of 64 μg/mL (broth) and 128 μg/mL (agar). | [63] |

| EEP inhibited P. gingivalis activity and induced cell death within 30 min by increasing membrane permeability. | |||

| Ursolic acid inhibited bactericidal activity with membrane rupture. Baccharin and artepillin C show bacteriostatic activities with membrane blebbing. | |||

| Propolis (Kopaonik, Serbia) | Periodontopathic bacteria: Fusobacterium nucleatum, Eikenella corrodens and Actinomyces odontolyticus and oral carcinogenic bacteria: Streptococcus mitis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis | Propolis with MIC value of 12.5 μg/mL inhibits all periodontopathic bacteria and oral carcinogenic bacteria except L. acidophilus with a MIC value of 6.3 μg/mL. | [64] |

| Propolis (Bangalore, India) | Streptococcus mutans (bacterial strain) and Candida albicans (yeast strain) | Propolis with a concentration of 50 μl shows 15.6 mm mean zone of inhibition for Candida albicans as compared to probiotics 12 mm and chlorhexidine 14 mm. | [65] |

| For Streptococcus mutans, mean zone of inhibition was 9.4 mm for probiotics, 14 mm for chlorhexidine, and 14.6 mm for propolis. | |||

| Propolis (Andean regions, Peru) | Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus gordonii | Treatment of methanolic fraction of propolis (chloroform partition) formed lower than average thickness biofilms of F. nucleatum and S. gordonii with concentrations of 1.563 mg/mL (7.37 ± 1.620 μm and 9.24 ± 0.679 μm) and 0.78 mg/mL (6.84 ± 1.68 µm and 8.02 ± 1.6 μm). | [66] |

| Cytotoxic assay of propolis (chloroform partition) on human gingival fibroblast cell line (HGF-1) at the 0.78 mg/mL dilution shows cell viability of 92.64%. | |||

| Antimicrobial study of methanolic fraction of propolis (chloroform residue) shows significant inhibition of F. nucleatum and S. gordonii bacteria with zone of inhibition, 12.15 ± 0.19 mm and 12.55 ± 0.19 mm in comparison to propolis combined with chlorhexidine (14.33 ± 0.19 mm and 14.55 ± 0.19 mm). | |||

| Propolis (City of Maceio, Alagoas State, north-eastern Brazil) | Periodontal pathogens present in multispecies biofilm | Propolis with a concentration of 1600 μg/mL shows no significant difference to sample treated with chlorohexidine and decreased the metabolic activity by 45%. | [67] |

| Propolis (City of Maceio, Alagoas State, north-eastern Brazil) | Periodontal pathogens present in multispecies biofilm | Propolis with a concentration of (400, 800, and 1600 μg/mL) was found to be effective in reducing metabolic activity of multispecies biofilms (7 days old) by 57, 56, and 56%, respectively, in comparison to 65% reduction with treatment of amoxicillin. | [68] |

| Propolis (South America) | Bacteria causing periodontal diseases (Porphyromonas gingivalis), yeast causing candida infections (Candida albicans), and bacteria causing dental caries (Streptococcus mutans) | MIC value of European EEP reported for P. gingivalis was 0.2 mg/mL, for C. albicans was 6.25 mg/mL, and for S. mutans was 0.2 mg/mL. | [69] |

| Periodontal biofilm containing bacterial counts 8.99 log10 CFU biofilm formation after 4 h was reduced to 3.21 log10 CFU by propolis with concentration of 100 mg/mL after 4 h treatment. | |||

| Carcinogenic control biofilm containing 7.99 log10 CFU biofilm formation after 4 h was reduced to bacterial count of 2.21 log10 CFU by propolis with concentration of 100 mg/mL after 4 h treatment. | |||

| Candida biofilm containing bacterial counts 7.74 log10 CFU biofilm formation after 4 h was reduced to 3.65 log10 CFU by propolis with concentration of 100 mg/mL after 4 h treatment. | |||

| Propolis (Belo Horizonte, Brazil) | Yeast strain—Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata | Propolis shows fungicidal and fungistatic activity on various Candida species, respectively, for C. albicans MIC values were 64–152 and 32–64 μg/mL, for C. tropicalis were 64 and 32–64 μg/mL, and for C. glabrata were 64–256 and 64 μg/mL. | [70] |

| Propolis (Okayama, Japan) | P. gingivalis W83 and C57BL/6 mice | Propolis treatment inhibited upregulation of serum endotoxin levels and downregulated P. gingivalis induced hepatic steatosis. | [71] |

| Propolis (Gwangju, Republic of Korea) | P. gingivalis KCOM 2804 and Wistar rats (weighing 250–400 g) | Finding shows MEC administration (L + LPS from P. gingivalis + MEC 1:34 group) showed significant reduction in alveolar bone loss and downregulated the expression levels of COX-2, COX-1, MMP- 8, iNOS, PGE2, and IL-8. | [73] |

| Propolis (Haj Umran city, Iraq) | Wistar rats (weighing 250–300 g) | Propolis irrigation after scaling root planning shows downregulation in TNF-α, IL-1β, and MDA serum levels as compared to control group with statistically significant difference of p < 0.05 | [74] |

| Royal jelly (RHF, Singapore.) | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Royal jelly with concentration range of 12.5–100 μg/mL shows inhibitory effects on periodontopathic bacteria. | [75] |

| Royal jelly (Uttar Pradesh, India) | Periodontopathic bacteria in subgingival plaque | Royal jelly with higher concentrations of 12.5 and 25 μg/mL shows inhibitory effects for anaerobic and aerobic periodontopathic bacteria. | [76] |

| Raw honey (Kanpur, India) | Escherichia coli | Zone of inhibition (ZI) for raw honey against patient isolated Escherichia coli with concentration of 75% and 100% is found to be 23 ± 0.666 and 27 ± 1.154 mm which was equivalent to standard tetracycline. | [77] |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | |||

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (Saint Louis, MO, USA) | P. gingivalis and human gingival fibroblasts | CAPE in a dose-dependent manner inhibits LPS induced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), interleukins (IL-8 and IL-6) production and inhibits protein kinase B (AKT) and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) phosphorylation. | [78] |

| Result of Western blot assay shows that lipopolysaccharide stimulated nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and TLR4/MyD88 activation was suppressed by CAPE treatment. | |||

| Purified bee venom (Suwon, Korea) | P. gingivalis, Balb/C mice and Mouse monocyte/macrophage RAW 264.7 cells | Purified bee venom (100 μg/kg) treatment reduces inflammatory bone loss related periodontitis by P. gingivalis and reduced expression of IL-1β and TNF-α in vivo. | [79] |

| Purified bee venom treatment suppressed osteoclast specific gene expression of TRAP, cathepsin K, integrin αVβ3, and NFATc1 and suppressed multinucleated osteoclast differentiation induced by RANKL. | |||

| Purified bee venom (Suwon, Korea) | P. gingivalis and HaCaT cell line | PGLPS upregulate expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, and TLR-4, in addition induced signaling pathway activation of inflammatory cytokines related transcription factors, AP-1, and NF-kB. | [80] |

| Further the treatment of bee venom (100 ng/mL) inhibited the pro-inflammatory cytokines by downregulation of AP-1 and NF-kB signaling pathways. | |||

| Melittin (Farmingdale, NY, USA) | P. gingivalis and HaCaT cell line | Melittin treatment with concentration of 1 μg/mL downregulated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine by suppressing signaling pathway activation of NF-kB, Akt, and ERK. | [81] |

| Bee Product/Country of Study | Participants | Interventions | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propolis (Matsudo, Japan) | Total participants (n = 24) Four groups: Group I—placebo (n = 6) Group II—propolis (n = 6) Group III—curry leaf (n = 6) Group IV—minocycline (n = 6) | Propolis ointment was given three times with a 1 month interval to tooth having periodontal pocket ≥ 5mm. | With propolis treatment P. gingivalis is significantly reduced in gingival crevicular fluid and improvement in score of clinical attachment level in propolis (1.67 ± 1.22 mm) is observed. | [82] |

| Propolis (Isfahan, Iran) | Total participants (n = 32) Two groups: Group I—propolis (n = 16) Group II—control (n = 16) | The propolis mouthwash (30 drops mixed with 20 mL water) was given to patients twice a day (gargle 1 min) with a 12-hour interval. | Results shows that there is no significant difference (p = 0.91) in plaque index (PI) score of propolis (85.19 ± 51.6%) in comparison to placebo group (83.93 ± 36.1%). | [83] |

| Result of papillary bleeding index (PBI) shows significant reduction in PBI of propolis group in comparison with placebo group with significant difference of p < 0.001 between two groups. | ||||

| Propolis (South-East, South Korea) | Patients were selected with at least one implant with PM. Total participants (n = 46) Two groups: Group I—propolis test group (n = 23) Group II—control test group (n = 23) | The test group were advised to use gel as toothpaste for 1 month 3 times/day. | In the test group a significant reduction is reported in probing depths (p = 0.27), plaque index score (p = 0.03), and bleeding on probing (p = 0.04) compared to control groups. | [84] |

| From baseline to 1 month follow up significant statistical reduction in Porphyromonas gingivalis (p = 0.05) and Tannerella forsythia (p = 0.02) was observed in the test group in comparison with the control group. | ||||

| Honey (Belagavi, Karnataka) | Total participants (n = 135) Three groups: Group I—manuka honey (n = 45) Group II—raw honey (n = 45) Group III—control (chlorhexidine) (n = 45) | Instructed to use 10 mL of honey mouthwash twice/day for the course of 21 days. | The GI score of raw honey mouthwash reduced from baseline 1.465 ± 0.17 to 22nd day 0.927 ± 0.26, score of manuka honey mouthwash reduced from baseline 1.457 ± 0.18 to 22nd day 0.976 ± 0.15. | [85] |

| The PI score of raw honey mouthwash reduced from baseline 1.525 ± 0.2 to 22nd day 0.723 ± 0.11, score of manuka honey mouthwash reduced from baseline 1.525 ± 0.2 to 22nd day 0.72 ± 0.12. | ||||

| Propolis (Seoul, South Korea) | Total participants (n = 80) Two groups: Group I—PME (n = 41) Group II—control or placebo (n = 39) | Patients diagnosed with incipient periodontitis or gingivitis was selected and the patients were advised to take 194 mg of PME capsule daily for the course of 8 weeks. | Result shows significant difference of p = 0.0406 in modified GI between test and control groups during 4 and 8 weeks. | [86] |

| Results of test group also reported that increase in salivary matrix metalloproteinase-9 and reduction in IL-6 was observed after 8 weeks. | ||||

| Propolis (Granada, Spain) | Total participants (n = 40) Four groups: Group I—placebo or control mouthwash (n = 10), Group II—0.2% chlorhexidine containing mouthwash (n = 10), Group III—2% propolis containing mouthwash (n = 10) and Group IV—0.2% chlorhexidine + 2% propolis (n = 10) | Patients for propolis mouthwash study was advised to use mouthwash 3 times/day for 2 days. | Result of propolis mouthwash assay shows reduction in bacterial proliferation, especially the mouthwash formulation of 0.2% chlorhexidine + 2% propolis reported < 105 CFU. | [87] |

| Result of propolis paste assay reported 90% of complete healing in periodontal sockets in comparison with control paste which shows 13.4% complete healing after 3 days of surgery. | ||||

| Propolis (Milan, Italy) | Total participants (n = 40) Two groups: Group I—test (phytoherbal group) (n = 20) Group II—control (placebo mouthwash) (n = 20) | Test group was instructed to rinse with mouthwash for 2 min, twice/day for the course of 3 months. | Both control group and test group show a statistically significant reduction from baseline to 3 months in the score of P.D. (CG p = 0.011, TG p = 0.001), FMPS (CG p = 0.003, TG p = 0.001), CAL (CG p = 0.020, TG p < 0.001), and FMBS (CG p = 0.002, TG p = 0.001). | [88] |

| Propolis (Pisa, Italy) | Total participants (n = 40) Two groups: Group I—control group (chlorhexidine gel formula + NSPT) Group II—test group (antioxidant gel formula + NSPT) | Propolis and herbs (antioxidant gel) as adjunctive therapy to non-standard periodontal treatment (NSPT). | Test group show better oxidation stress reduction results as compared to placebo group. | [89] |

| Propolis (Udaipur, India) | Total participants (n = 120) Four groups: Group I—hot EEP (n = 30), Group II—cold EEP (n = 30), Group III—0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate (n = 30) and Group IV—placebo (distilled water) (n = 30) | Advised to use mouthrinse twice a day for the course of 3 months. | Result shows decline in S. mutans concentration after use of mouth rinse p < 0.05. | [90] |

| The cell count of S. mutans and L. acidophilus is found to be decreased in comparison to baseline with use of chlorhexidine mouthwash (5.8 × 102) and hot ethanolic propolis mouthwash (5.5 × 102). | ||||

| Significant reduction in plaque scores was observed after the course of 3 months in cold ethanolic propolis (0.46), hot ethanolic propolis (0.47), and chlorhexidine (0.45) mouthwash groups. | ||||

| Propolis (Katowice, Poland) | Total participants (n = 50) Two groups: Group I—test group (active ingredient) (n = 25) Group II—control group (placebo) (n = 25) | Patients advised to brush teeth with propolis toothpaste 3 times/day for 3 min over the course of 35 days. | In group A (used toothpaste with propolis and plant oils) for gingival condition, GBI was significantly decreased for molars p = 0.0017, for incisors p = 0.007, and total GBI p = 0.002. | [91] |

| Significant improvement in oral hygiene index (OHI) was observed p = 0.011. | ||||

| Propolis (Mashhad, Iran) | Total participants (n = 40) Two groups: Group I—test group (propolis mouthwash) (n = 20) Group II—control group (chlorhexidine mouthwash) (n = 20) | Test group was advised to use propolis mouthwash for 3 weeks after brushing their teeth twice/day consecutively. | A statistically significant difference between the score of periodontal index (p = 0.005), PI (p < 0.001) and GI (p = 0.006) in the test group is observed. | [92] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, M.; Prakash, S.; Radha; Lorenzo, J.M.; Chandran, D.; Dhumal, S.; Dey, A.; Senapathy, M.; Rais, N.; Singh, S.; et al. Apitherapy and Periodontal Disease: Insights into In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050823

Kumar M, Prakash S, Radha, Lorenzo JM, Chandran D, Dhumal S, Dey A, Senapathy M, Rais N, Singh S, et al. Apitherapy and Periodontal Disease: Insights into In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies. Antioxidants. 2022; 11(5):823. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050823

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Manoj, Suraj Prakash, Radha, José M. Lorenzo, Deepak Chandran, Sangram Dhumal, Abhijit Dey, Marisennayya Senapathy, Nadeem Rais, Surinder Singh, and et al. 2022. "Apitherapy and Periodontal Disease: Insights into In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies" Antioxidants 11, no. 5: 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050823

APA StyleKumar, M., Prakash, S., Radha, Lorenzo, J. M., Chandran, D., Dhumal, S., Dey, A., Senapathy, M., Rais, N., Singh, S., Kalkreuter, P., Damale, R. D., Natta, S., Vishvanathan, M., Sathyaseelan, S. K., Rajalingam, S., Viswanathan, S., Murugesan, Y., Muthukumar, M., ... Mekhemar, M. (2022). Apitherapy and Periodontal Disease: Insights into In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Studies. Antioxidants, 11(5), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050823