Production and Role of Nitric Oxide in Endometrial Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Endometrial Cancer

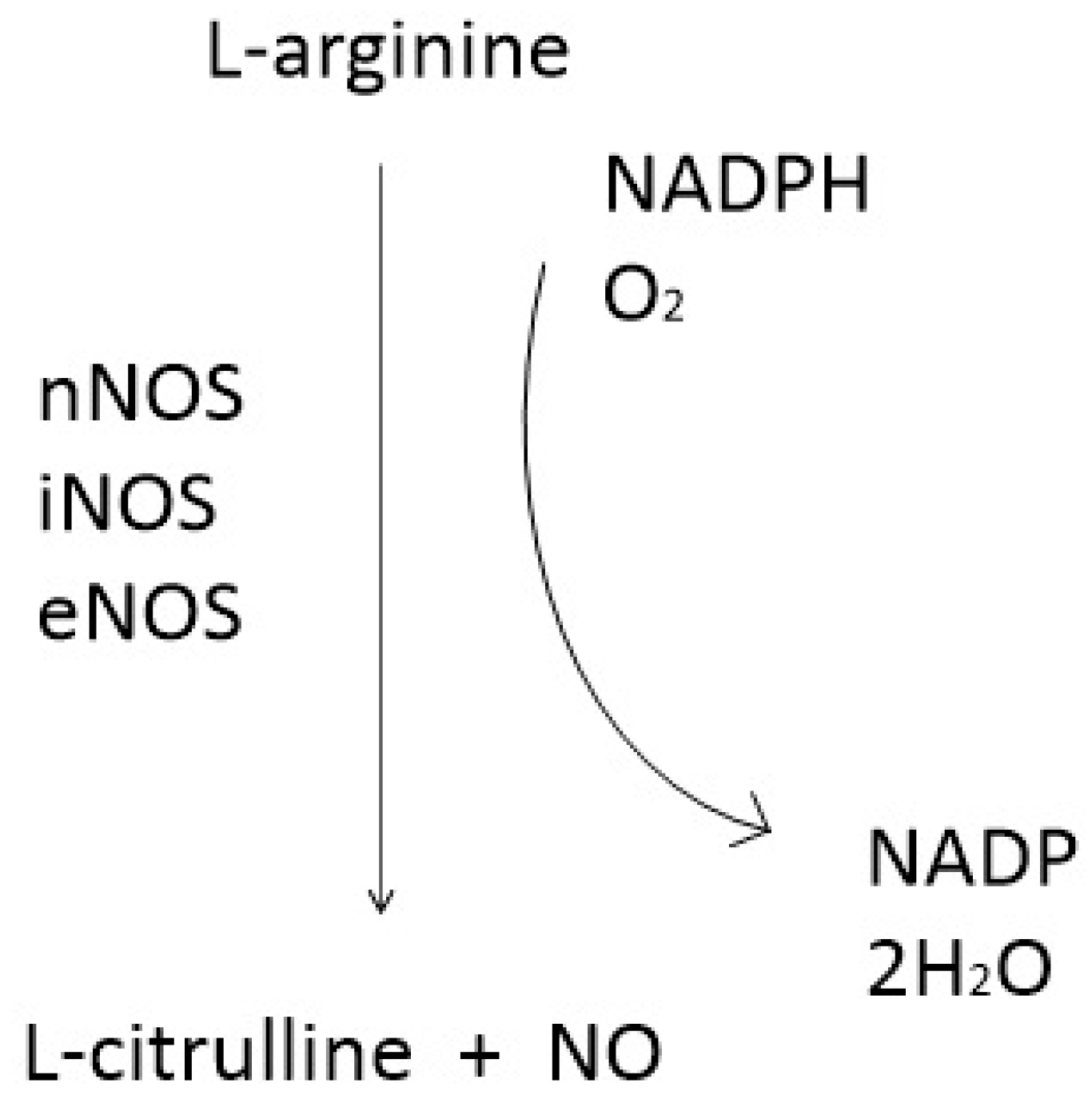

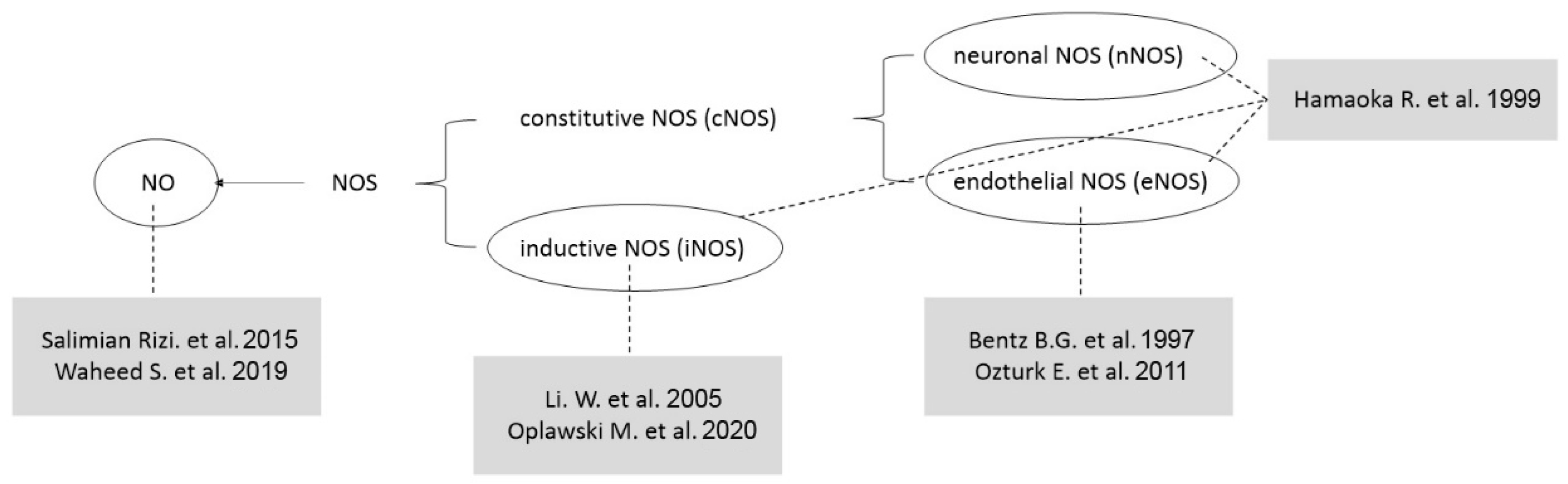

1.2. NO and Nitric Oxide Synthase

1.2.1. NO and Tumors

1.2.2. NO and Gynaecological Cancer

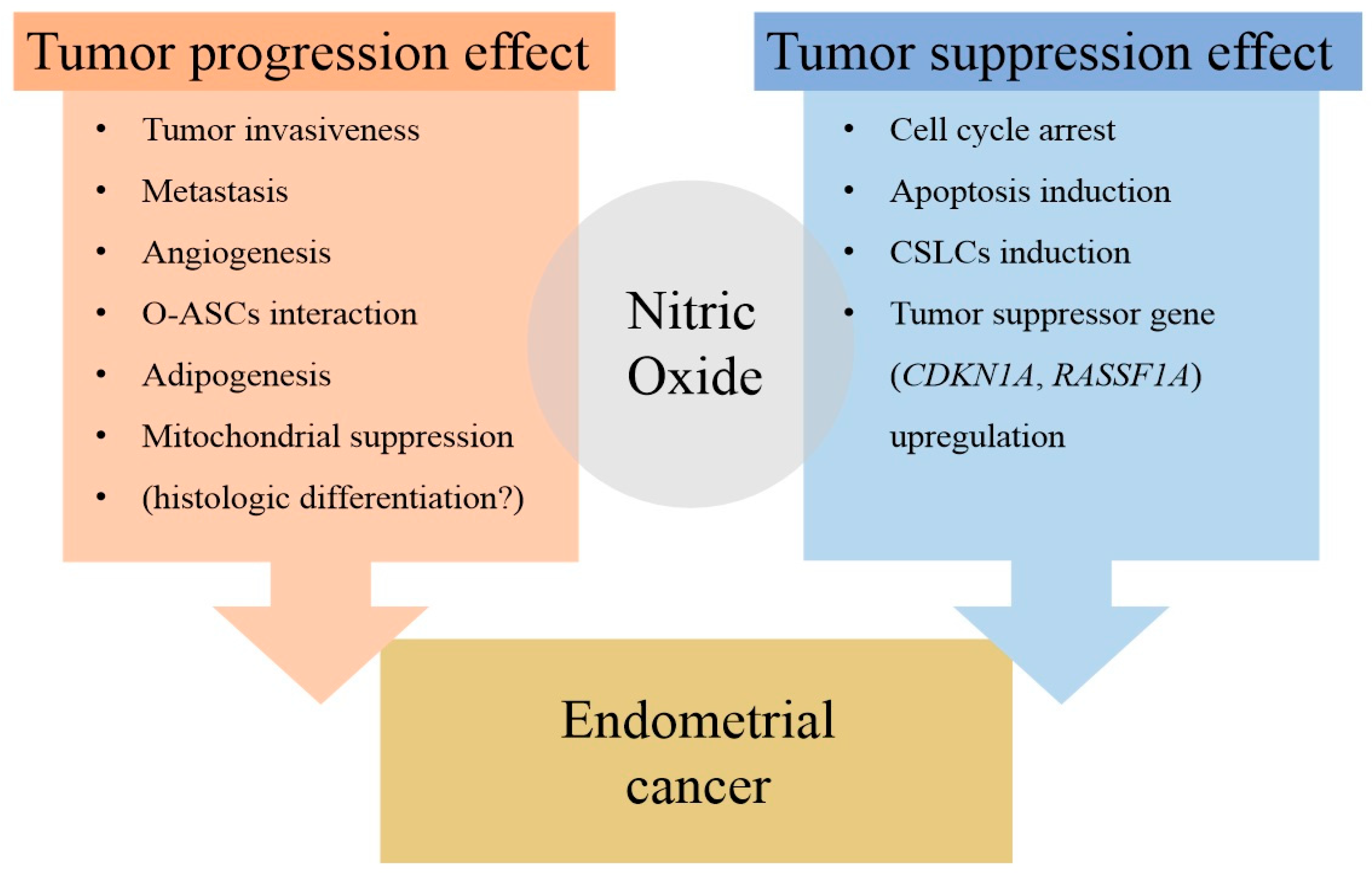

2. NO in Endometrial Cancer

2.1. Studies on the Role of NO in the Initiation of Endometrial Cancer

2.1.1. eNOS

2.1.2. iNOS

2.1.3. iNOS, eNOS, and nNOS

2.1.4. NO

2.2. Studies on the Antitumor Effects of NO in Endometrial Cancer

2.3. Integrating ProMisE Molecular Classification with NO Signaling Pathway

2.4. Summary

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holloway, R.W. Treatment options for endometrial cancer: Experience with topotecan. Gynecol. Oncol. 2003, 90, S28–S33. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. General Information About Endometrial Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/uterine/hp/endometrial-treatment-pdq#_1 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Resnick, K.E.; Hampel, H.; Fishel, R.; Cohn, D.E. Current and emerging trends in Lynch syndrome identification in women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 114, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, A.K.; Lindor, N.M.; Winship, I.; Tucker, K.M.; Buchanan, D.D.; Young, J.P.; Rosty, C.; Leggett, B.; Giles, G.G.; Goldblatt, J.; et al. Risks of colorectal and other cancers after endometrial cancer for women with Lynch syndrome. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermair, A.; Youlden, D.R.; Young, J.P.; Lindor, N.M.; Baron, J.A.; Newcomb, P.; Parry, S.; Hopper, J.L.; Haile, R.; Jenkins, M.A. Risk of endometrial cancer for women diagnosed with HNPCC related colorectal carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2678–2684. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D.D.; Tan, Y.Y.; Walsh, M.D.; Clendenning, M.; Metcalf, A.M.; Ferguson, K.; Arnold, S.T.; Thompson, B.A.; Lose, F.A.; Parsons, M.T.; et al. Tumor mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and DNA MLH1 methylation testing of patients with endometrial cancer diagnosed at age younger than 60 years optimizes triage for population-level germline mismatch repair gene mutation testing. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S.E.; Aronson, M.; Pollett, A.; Eiriksson, L.R.; Oza, A.M.; Gallinger, S.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Alvandi, Z.; Bernardini, M.Q.; MacKay, H.J.; et al. Performance characteristics of screening strategies for Lynch syndrome in unselected women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer who have undergone universal germline mutation testing. Cancer 2014, 120, 3932–3939. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, P.J.; Billingsley, C.C.; Lankes, H.A.; Ali, S.; Cohn, D.E.; Broaddus, R.J.; Ramirez, N.; Pritchard, C.C.; Hampel, H.; Chassen, A.S.; et al. Combined Microsatellite Instability, MLH1 Methylation Analysis, and Immunohistochemistry for Lynch Syndrome Screening in Endometrial Cancers From GOG210: An NRG Oncology and Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4301–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.C.; Yang, E.J.; Muto, M.G.; Feltmate, C.M.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Horowitz, N.S.; Syngal, S.; Yurgelun, M.B.; Chittenden, A.; Hornick, J.L.; et al. Universal Screening for Mismatch-Repair Deficiency in Endometrial Cancers to Identify Patients With Lynch Syndrome and Lynch-like Syndrome. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2017, 36, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.S.; Scott, J.L.; Gilks, C.B.; Daniels, M.S.; Sun, C.C.; Lu, K.H. Testing women with endometrial cancer to detect Lynch syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, L.; Balaguer, F.; Lindor, N.; De La Chapelle, A.; Hampel, H.; Aaltonen, L.A.; Hopper, J.L.; Le Marchand, L.; Gallinger, S.; Newcomb, P.A.; et al. Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA 2012, 308, 1555–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Abeloff, M.D.; Armitage, J.O.; Niederhuber, J.E.; Kastan, M.B.; McKenna, W.G. Review of clinical oncology. Churchill Livingstone 2004, 61, 1281. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, D.; Filiaci, V.; Randall, M.E.; Mutch, D.; Steinhoff, M.M.; DiSilvestro, P.A.; Moxley, K.M.; Kim, Y.M.; Powell, M.A.; O’Malley, D.M.; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy plus Radiation for Locally Advanced Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2317–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, R.N.; Sill, M.W.; Beffa, L.; Moore, R.G.; Hope, J.M.; Musa, F.B.; Mannel, R.; Shahin, M.S.; Cantuaria, G.H.; Girda, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; Christensen, R.D.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, D.; Patel, V.; Banerjee, D. Nitric Oxide and S-Nitrosylation in Cancers: Emphasis on Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2020, 22, 1178223419882688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Soud, H.; Gachhui, R.; Raushel, F.M.; Stuehr, D.J. The ferrous-dioxy complex of neuronal nitric oxide synthase: Divergent effects of l-arginine and tetrahydrobiopterin on its stability. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 75, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kone, B.C.; Kuncewicz, T.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Z.-Y. Protein interactions with nitric oxide synthases: Controlling the right time, the right place, and the right amount of nitric oxide. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2003, 285, F178–F190. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking, J.; Xie, Q.W.; Nathan, C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Biological Role of Nitric Oxide. Acute Crit. Care 1998, 13, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Ljunggren-Rose, A.; Chandramohan, N.; Whetsell, W.O., Jr.; Sriram, S. In vitro and in vivo induction and activation of nNOS by LPS in oligodendrocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 229, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.K. Injury-coupled induction of endothelial eNOS and COX-2 genes: A paradigm for thromboresistant gene therapy. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 1998, 110, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yim, C.Y. Nitric Oxide and Cancer. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2010, 78, 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M.; Mutoh, M.; Kawamori, T.; Sugimura, T.; Wakabayashi, K. Altered expression of beta-catenin, inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoi, W.; Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Kokura, S.; Mizushima, K.; Takanami, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Tanimura, Y.; Hung, L.P.; Koyama, R.; et al. Regular exercise reduces colon tumorigenesis associated with suppression of iNOS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 399, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A. Chemoprevention with phytochemicals targeting inducible nitric oxide synthase. In Food Factors for Health Promotion; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 61, pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gochman, E.; Mahajna, J.; Shenzer, P.; Dahan, A.; Blatt, A.; Elyakim, R.; Reznick, A.Z. The expression of iNOS and nitrotyrosine in colitis and colon cancer in humans. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotti, A.W.; Fahey, J.F.; Korytowski, W. Role of nitric oxide in hyper-aggressiveness of tumor cells that survive various anti-cancer therapies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 179, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.M.; Girotti, A.W. Nitric oxide-mediated resistance to photodynamic therapy in a human breast tumor xenograft model: Improved outcomes with NOS2 inhibitors. Nitric Oxide 2017, 62, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick, R.; Girotti, A.W. Pro-survival and pro-growth effects of stress-induced nitric oxide in a prostate cancer photodynamic therapy model. Cancer Lett. 2014, 343, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, J.M.; Girotti, A.W. Accelerated migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells after a photodynamic therapy-like challenge: Role of nitric oxide. Nitric Oxide 2015, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, J.M.; Emmer, J.V.; Korytowski, W.; Hogg, N.; Girotti, A.W. Antagonistic effects of endogenous nitric oxide in a glioblastoma photodynamic therapy model. Photochem. Photobiol. 2016, 92, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girotti, A.W. Nitric oxide-mediated resistance to antitumor photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.P.; He, P.; Subleski, J.; Hofseth, L.J.; Trivers, G.E.; Mechanic, L.; Hofseth, A.B.; Bernard, M.; Schwank, J.; Nguyen, G.; et al. Nitric oxide is a key component in inflammation-accelerated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7130–7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenot, J.D.; Rudensky, A.Y. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: Regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, M.; Schultze, J.L. Regulatory T cells in cancer. Blood 2006, 108, 804–811. [Google Scholar]

- Njah, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Qiu, B.; Arumugam, S.; Raju, A.; Pobbati, A.V.; Lakshmanan, M.; Tergaonkar, V.; Thibault, G.; Wang, X.; et al. A Role of Agrin in Maintaining the Stability of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 during Tumor Angiogenesis. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 949–965. [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza, C.; Araos, J.; Naranjo, L.; Barros, E.; Subiabre, M.; Toledo, F.; Gutiérrez, J.; Chiarello, D.I.; Pardo, F.; Leiva, A.; et al. Nitric oxide and pH modulation in gynaecological cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshkin, S.J.; Greco, M.R.; Cardone, R.A. Role of pHi, and proton transporters in oncogenedriven neoplastic transformation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130100. [Google Scholar]

- Harguindey, S.; Arranz, J.L.; Polo Orozco, J.D.; Rauch, C.; Fais, S.; Cardone, R.A.; Reshkin, S.J. Cariporide and other new and powerful NHE1 inhibitors as potentially selective anticancer drugs—An integral molecular/biochemical/metabolic/clinical approach after one hundred years of cancer research. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Astekar, M.; Soi, S.; Manjunatha, B.; Shetty, D.; Radhakrishnan, R. pH gradient reversal: An emerging hallmark of cancers. Recent Pat. Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 244–258. [Google Scholar]

- Glunde, K.; Guggino, S.E.; Solaiyappan, M.; Pathak, A.P.; Ichikawa, Y.; Bhujwalla, Z.M. Extracellular acidification alters lysosomal trafficking in human breast cancer cells. Neoplasia 2003, 5, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zhoughbi, W.; Huang, J.; Paramasivan, G.S.; Till, H.; Pichler, M.; Guertl-Lackner, B.; Hoefler, G. Tumor macroenvironment and metabolism. Semin. Oncol. 2014, 41, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, T.; Hiasa, M.; Nagata, Y.; Okui, T.; White, F. Contribution of acidic extracellular microenvironment of cancer-colonized bone to bone pain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 2677–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liams, E.L.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Nitric oxide and metastatic cell behaviour. BioEssays 2005, 27, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Wang, L.; Mollica, M.; Re, A.T.; Wu, S.; Zuo, L. Nitric oxide in cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2014, 353, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G. Diagnosis and management of bacterial vaginosis and other types of abnormal vaginal bacterial flora: A review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2010, 65, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.K.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 15, 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykke, M.R.; Becher, N.; Haahr, T.; Boedtkjer, E.; Jensen, J.S.; Uldbjerg, N. Vaginal, Cervical and Uterine pH in Women with Normal and Abnormal Vaginal Microbiota. Pathogens 2021, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, B.G.; Barnes, M.N.; Haines, G.K.; Lurain, J.R.; Hanson, D.G.; Radosevich, J.A. Cytoplasmic Localization of Endothelial Constitutive Nitric Oxide Synthase in Endometrial Carcinomas. Tumor Biol. 1997, 18, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, E.; Dikensoy, E.; Balat, O.; Ugur, M.G.; Oguzkan Balci, S.; Aydin, A.; Kazanci, U.; Pehlivan, S. Association of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Gene Polymorphisms with Endometrial Carcinoma: A Preliminary Study. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2011, 12, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, R.-J.; Jiang, L.-H.; Shi, J.; Long, X.; Fan, B. Expression of Cyclooxygenase-2 and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Correlates with Tumor Angiogenesis in Endometrial Carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2005, 22, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oplawski, M.; Dziobek, K.; Zmarzły, N.; Grabarek, B.O.; Kiełbasiński, R.; Kieszkowski, P.; Januszyk, P.; Talkowski, K.; Schweizer, M.; Kras, P.; et al. Variances in the Level of COX-2 and INOS in Different Grades of Endometrial Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaoka, R.; Yaginuma, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Fujii, J.; Koizumi, M.; Seo, H.G.; Hatanaka, Y.; Hashizume, K.; Ii, K.; Miyagawa, J.-I.; et al. Different Expression Patterns of Nitric Oxide Synthase Isozymes in Various Gynecological Cancers. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 125, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimian Rizi, B.; Caneba, C.; Nowicka, A.; Nabiyar, A.W.; Liu, X.; Chen, K.; Klopp, A.; Nagrath, D. Nitric Oxide Mediates Metabolic Coupling of Omentum-Derived Adipose Stroma to Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, S.; Cheng, R.Y.; Casablanca, Y.; Maxwell, G.L.; Wink, D.A.; Syed, V. Nitric Oxide Donor DETA/NO Inhibits the Growth of Endometrial Cancer Cells by Upregulating the Expression of RASSF1 and CDKN1A. Molecules 2019, 24, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavida, B.; Garban, H. Nitric Oxide-Mediated Sensitization of Resistant Tumor Cells to Apoptosis by Chemo-Immunotherapeutics. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbik, M.; Szulc-Kielbik, I.; Nowak, M.; Sulowska, Z.; Klink, M. Evaluation of Nitric Oxide Donors Impact on Cisplatin Resistance in Various Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Toxicol. Vitr. 2016, 36, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Messeih, P.L.; Nosseir, N.M.; Bakhe, O.H. Evaluation of Inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress Markers in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Curative Radiotherapy. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 1, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Y. Nitric Oxide Donor-Based Cancer Therapy: Advances and Prospects. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7617–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, F.; Kashfi, K.; Nath, N. The Dual Role of INOS in Cancer. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.D.; Espey, M.G.; Ridnour, L.A.; Hofseth, L.J.; Mancardi, D.; Harris, C.C.; Wink, D.A. Hypoxic Inducible Factor 1α, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase, and P53 Are Regulated by Distinct Threshold Concentrations of Nitric Oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8894–8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaupel, P.; Kallinowski, F.; Okunieff, P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: A review. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 6449–6465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, J.R. Are cancer cells acidic? Br. J. Cancer 1991, 64, 425–427. [Google Scholar]

- Boedtkjer, E.; Bunch, L.; Pedersen, S.F. Physiology, pharmacology and pathophysiology of the pH regulatory transport proteins NHE1 and NBCn1: Similarities, differences and implications for cancer therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 1345–1371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boedtkjer, E.; Pedersen, S.F. The Acidic Tumor Microenvironment as a Driver of Cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author [Reference] | Study Design | Species and/or Sample | Detection Method | Target Gene(s) or Pathway(s) Associated with NOS | Results/Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentz B.G. et al. (1996) [51] | Human sample study | 50 patients (42 endometrioid adenocarcinomas, 4 serous papillary carcinomas, 2 clear cell carcinomas, 2 adenosquamous carcinomas) | ecNOS immunostaining, H&E staining | ecNOS | Normal and hyperplastic endometrial glands exhibited moderate cytoplasmic and weak nuclear ecNOS staining in a small percentage of cells. There was a broad range of ecNOS expression in endometrial carcinomas, predominantly in the cytoplasm and nuclei. Endometrioid tumors invading more than 1/2 of myometrial thickness (n = 18), had significantly higher cytoplasmic staining than those tumors limited to the inner 1/2 of myometrium. And Moreover, patients with higher ecNOS staining tended to have shorter disease-free survival. Cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of ecNOS was found in endometrial carcinoma. Increased cytoplasmic ecNOS staining intensity was correlated with increased myometrial invasion. Patients with higher ecNOS staining tended to have shorter disease-free survival. |

| Ozturk E. et al. (2011) [52] | Human sample study | 89 patients diagnosed with the endometrioid type of endometrial carcinoma. | PCR, RFLP | eNOS | An analysis of eNOS gene polymorphisms in a Turkish population revealed that frequencies of the BB genotype of the VNTR intron 4 polymorphism and the TT genotype of the c.894G>T polymorphism were significantly higher in the endometrial cancer group. c.894G>T and VNTR intron 4 polymorphisms in the eNOS gene could be intriguing susceptibility factors that modulate an individual’s risk of endothelial cancer. |

| Wei Li et al. (2005) [53] | Human sample study | 30 patients with primary endometrial carcinoma | Immunohistochemistry, microvessel counting | iNOS | COX-2 and iNOS positivity rates in samples from primary endometrial carcinoma were 66.7% and 73.3, respectively. The percentage of iNOS positivity was higher in patients with deep myometrial invasion than in patients with no or less than 50% myometrial invasion. Both COX-2 and iNOS were significantly correlated with microvessel density. Combined expression of COX-2 and iNOS may play an important role in the development and invasion of endometrial cancer, possibly through modulation of angiogenesis by COX-2 and iNOS, at least in part. |

| Oplawski M. et al. (2020) [54] | Human sample study | 45 women with endometrial cancer divided according to the degree of histological differentiation (G1, 17; G2, 15; G3, 13.) Control, 15 | Immunohistochemical staining, light microscopy | iNOS | The optical density of iNOS immunostaining in endometrial cancer samples was increased by 147%, 243% and 241% relative to controls in well-differentiation (G1), moderately differentiated (G2) and poorly differentiated (G3) cancers, respectively, with COX-2 expression following a similar pattern. Expression of COX-2 and iNOS may be useful in predicting the progression of endometrial cancer and treatment effectiveness. |

| Hamaoka R. et al. (1998) [55] | Human sample study | 24 cases of ovarian cancer, 12 uterocervical cancers, and 27 endometrial cancers; 22 uninvolved tissues from cervical and endometrial cancer. | RT-PCR, southern blotting, SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting | NOSⅠ (nNOS), NOSⅡ (eNOS) | All clear-cell adenocarcinomas and most serous-type adenocarcinomas expressed both NOS1 and NOS2, whereas most uterine squamous carcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas expressed only NOS2. There was no correlation between the frequency of NOS expression and patients’ age or clinical stage of the disease. Because NO increases vascular permeability and blood flow, the high frequency of NOS expression in gynecological cancers may serve to stimulate and promote tumor growth. |

| Salimian R. et al. (2015) [56] | Tissue samples and cell lines study | O-ASC (omental adipose stromal cells), human ovarian and endometrial carcinoma cell lines, OVCAR429, HEC-1A | Quantitative analysis of NO (Sievers NO analyzer), cell viability analysis (hemocytometer counting), UPLC | NO | Co-culture of O-ASCs with cancer cell increased NO synthesis and enhanced proliferation of cancer cells compared with cancer cells cultured alone. Treatment with the NOS inhibitor, L-NAME, attenuated the proliferation-potentiating effect of O-ASC co-culture, suggesting that the effect of O-ASCs on cancer cell proliferation is mediated by NO signaling. In parallel experiments, a low concentration of the NO donor, SNAP, increased growth of cancer cells, whereas higher concentrations exerted cytotoxic effects. The increase in NO synthesis in cancer cells induced by co-culture with O-ASCs resulted in suppression of cancer cell mitochondrial respiration. Adipogenesis in O-ASCs was also increased by co-culture with cancer cells, an effect mediated through secreted citrulline. Addition of L-arginase (the substrate for NOS) or L-NAME increased chemosensitivity of cancer cells to paclitaxel. Patient-derived O-ASCs increase NO levels in ovarian and endometrial cancer cells and promote their proliferation. O-ASCs upregulate glycolysis and reduce ROS in cancer cells by increasing NO levels through paracrine secretion of metabolites. O-ASC-mediated chemoresistance in cancer cells can be deregulated by altering NO homeostasis through L-arginase or L-NAME. |

| Waheed S. et al. (2019) [57] | Cell line study | 4 endometrial cancer cell lines (AN3CA, KLE, HEC-1B, Ishikawa) | Cell-cycle analysis, Hoechst dye efflux assay, transcriptome profiling by RNA-Seq, first phase in-house data analysis, second phase data analysis, western blot analysis, cell proliferation assay, cell invasion assay, soft-agar colony formation assay, knockdown of RASSF1/CDKN1A | DETA/NO | DETA/NO treatment of endometrial cancer cells attenuated endometrial cancer cell proliferation in associated with a marked increase in the proportion of G2/M phase cells, reflecting an arrest of cells in the G1 phase and accumulation of a sub-G1 (G0) apoptotic population. In addition, DETA/NO treatment significantly reduced the percentage of CSLCs (cancer stem-like cells). From a mechanistic standpoint, an RNA-seq analysis suggested the possible involvement of upregulation of CDKN1A and RASSF1A, the latter of which downregulated the expression of cyclins. DETA/NO exerts antitumor effects through inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, G2/M arrest, attenuation of CSLS number, reduced expression of CSLS markers, and induction of tumor suppressor genes. These results suggest the potential use of DETA/NO as an effective antitumor treatment for endometrial cancer patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeo, S.G.; Oh, Y.J.; Lee, J.M.; Yeo, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Park, D.C. Production and Role of Nitric Oxide in Endometrial Cancer. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14030369

Yeo SG, Oh YJ, Lee JM, Yeo JH, Kim SS, Park DC. Production and Role of Nitric Oxide in Endometrial Cancer. Antioxidants. 2025; 14(3):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14030369

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeo, Seung Geun, Yeon Ju Oh, Jae Min Lee, Joon Hyung Yeo, Sung Soo Kim, and Dong Choon Park. 2025. "Production and Role of Nitric Oxide in Endometrial Cancer" Antioxidants 14, no. 3: 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14030369

APA StyleYeo, S. G., Oh, Y. J., Lee, J. M., Yeo, J. H., Kim, S. S., & Park, D. C. (2025). Production and Role of Nitric Oxide in Endometrial Cancer. Antioxidants, 14(3), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14030369