Vaccine Champions Training Program: Empowering Community Leaders to Advocate for COVID-19 Vaccines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

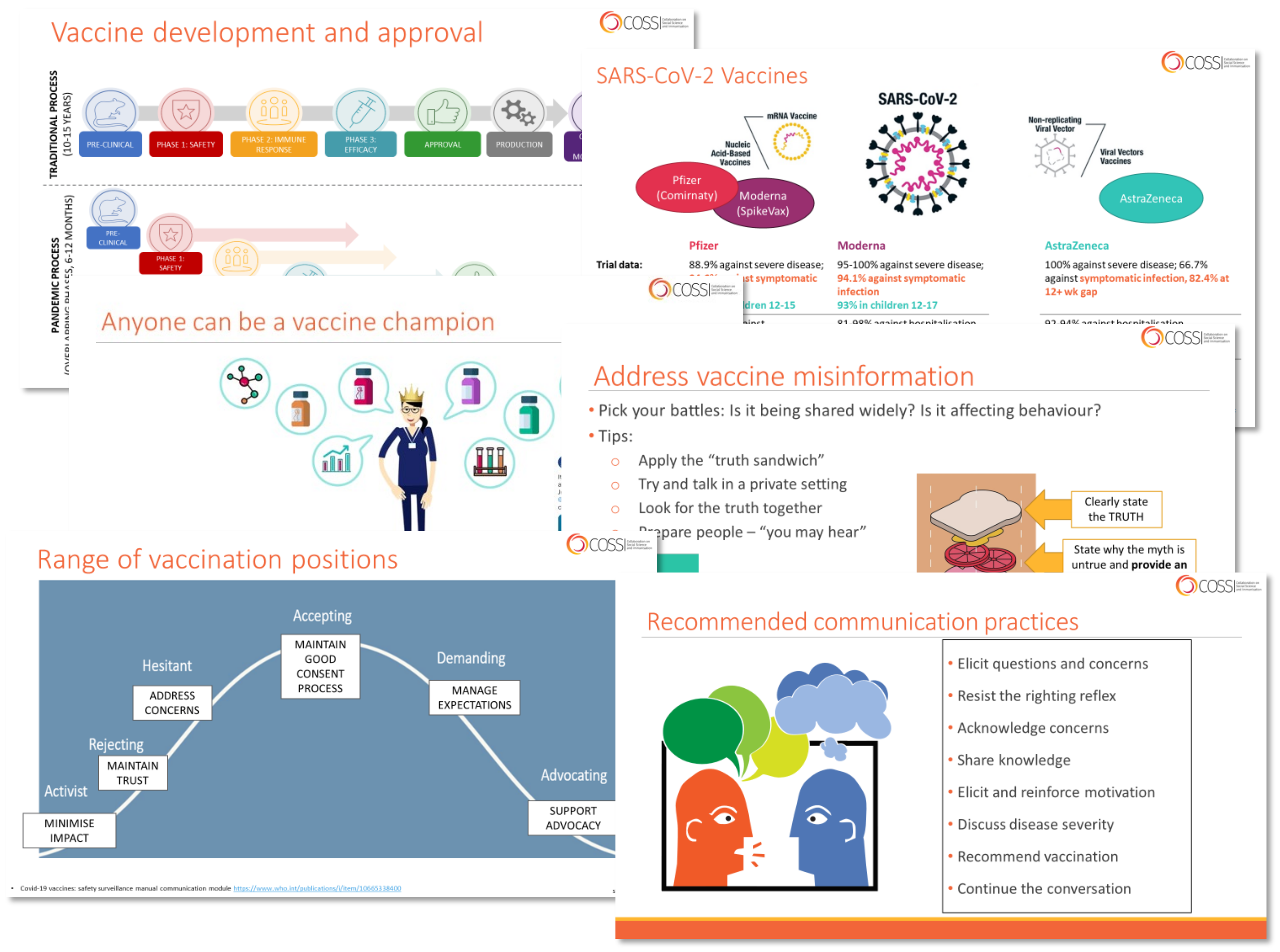

Overview of the Vaccine Champions Program

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Confidence and Satisfaction

3.3. Training Experience and Feedback

3.3.1. Content

“The role play was really good… they did a really good job addressing how to be open and have a chat with people, because everyone has different concerns, so I thought the session was quite useful.”

“The graph that showed the protection of the booster shot…we used that in our social media for the multicultural communities, it was a really good way for them to understand the impact.”

3.3.2. Format

3.3.3. Experiences of Formal Vaccine Champions Delivering Vaccine Information Sessions

“There was a GP, a pathologist, and an infectious disease specialist…I ran through as if I’m asking the questions and they would answer…in the South Asian community it was more of a video to be shared through our WhatsApp channels and various social media channels as well.”

“I think it was probably too long for someone to sit in front of a screen for as well, in the evening. So, we looked at short messaging…we got a lot more engagement with those kinds of things.”

3.3.4. Experiences of Informal Vaccine Champions in the Community

“I think it’s not done yet, so I think the program needs to continue and have up-to-date information for us to just keep our heads around what’s relevant now.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

| Question | Response Options |

|---|---|

| Comparing your level of confidence before and after attending the session: | |

| How confident are you in your ability to find appropriate resources on COVID-19 vaccination information? |

|

| How confident are you in your ability to talk about the risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccines? |

|

| How confident are you in your ability to answer difficult questions about COVID-19 vaccines? |

|

| How likely are you to initiate a conversation about COVID-19 vaccines with a person who might be hesitant? |

|

| Please rate how satisfied you were with the following: The information about vaccine safety and effectiveness |

|

| The strategies for discussing vaccines with a hesitant person |

|

| The example conversation/s (role play) |

|

| The question and answer sections of the session |

|

| The quality of the presenters |

|

| How did you find the length of the session? |

|

| Which best describes the group or network through which you attended this training? |

|

| In General: |

|---|

| To do a quick round of introductions: tell me your first name, in what capacity you attended the session (e.g., a health care worker), roughly when you attended the session, and if you went on to deliver any sessions yourself? |

| Thinking about the initial session? |

| What community group/session did you attend? (both) Specific to health workers, general? Did you go to more than one session? Did you set up any other sessions afterwards? |

| How did you find the session? (both) What did you like? What could be improved? How did you find the presenter? Was there any information you wanted to know more about that wasn’t included? Did it meet your expectations? Did it give you what you needed? |

| What did you think about the content? (both) Was it pitched at the right level? Was it too complicated or too simple? What did you think about the information on vaccines? What did you think about the information about supporting vaccination and having discussions? What did you like? What could be improved? |

| What did you think about the format? (both) What about the slides? If it was held in person, would it have been different? How so? Did you refer back to the slides afterwards? That was all the questions I had about the session delivered by MCRI specifically. |

| Champions–delivering sessions and skills learnt |

| If you signed up to be a champion, what was your understanding of what would be involved? (champions) What made you decide to do it? |

| How did you find delivering your own sessions? (champions) What went well? What could be improved? Did you end up delivering a session? How many? Which community groups did you deliver the sessions to? If delivered a number of sessions-did they change over time? |

| Can you give an example of how the training session prepared you to deliver the program? Or how it didn’t prepare you? (champions) |

| Tell me about the materials? (champions) Did you have to adapt the session to work for you? Describe any changes you made? What materials could have made it better? Simpler slides? Flip charts? Role play? Lesson plan? How did you find the process of getting materials from Department? What did you like? What could be improved? |

| When talking about the practically of it all: (champions) How did the department book sessions for you? Were the sessions well organised? Who was there? Did you have any say over presenting? |

| Using skills |

| Tell me about any occasions, where you have applied the skills, strategies, or knowledge you learned from the training? (both) [Outside of the community sessions] If not, why do you think that is? Is there anything stopping you? Tell me an example of when you spoke to someone, or used skills, or changed someone’s mind. |

| What was most impactful thing you were involved in, from your perspective? (both) What made the biggest bang for buck? Was it having big sessions? One on one conversations? |

| Future |

| What aspects of this process should we carry forward? Or will you carry forward? (both) What do you hope to take forward? Would you use skills to talk about other vaccines? Benefits to future community sessions? Would you organise your own session if DH don’t? Should we continue to train people to talk to vaccine as we move out of covid/not? What is the legacy of this work? For yourself/for the department? |

| Is there anything else you would like to tell me, about the Vaccine Champions Training Session, that we haven’t covered? (both) |

References

- Edwards, B.; Biddle, N.; Gray, M.; Sollis, K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: Correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J.; Bagot, K.L.; Hoq, M.; Leask, J.; Seale, H.; Biezen, R.; Sanci, L.; Manski-Nankervis, J.A.; Bell, J.S.; Munro, J.; et al. Factors Influencing Australian Healthcare Workers’ COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions across Settings: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Hoq, M.; Measey, M.A.; Danchin, M. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Murphy, S.; Mau, V.; Bryant, R.; O’Donnell, M.; McMahon, T.; Nickerson, A. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst refugees in Australia. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1997173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.; Rutherford, S.; Borkoles, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Younger Women in Rural Australia. Vaccines 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Tuckerman, J.; Bonner, C.; Durrheim, D.N.; Trevena, L.; Thomas, S.; Danchin, M. Parent-level barriers to uptake of childhood vaccination: A global overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, K.J.; Dodd, R.H.; Cvejic, E.; Ayrek, J.; Batcup, C.; Isautier, J.M.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Pickles, K.; Nickel, B.; et al. Health literacy and disparities in COVID-19-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours in Australia. Public Health Res. Pract. 2020, 30, e30342012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.; Pan, D.; Nevill, C.R.; Gray, L.J.; Martin, C.A.; Nazareth, J.; Minhas, J.S.; Divall, P.; Khunti, K.; Abrams, K.R.; et al. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. COVID-19 Mortality in Australia: Deaths Registered Until 30 June 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/covid-19-mortality-australia-deaths-registered-until-30-june-2022 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Graham, S.; Blaxland, M.; Bolt, R.; Beadman, M.; Gardner, K.; Martin, K.; Doyle, M.; Beetson, K.; Murphy, D.; Bell, S.; et al. Aboriginal peoples’ perspectives about COVID-19 vaccines and motivations to seek vaccination: A qualitative study. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, E. Mastering the art of persuasion during a pandemic. Nature 2022, 610, S34–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, K.; Freeman, M. I Immunise: An evaluation of a values-based campaign to change attitudes and beliefs. Vaccine 2015, 33, 6235–6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duru, J.I.; Usman, S.; Adeosun, O.; Stamidis, K.V.; Bologna, L. Contributions of Volunteer Community Mobilizers to Polio Eradication in Nigeria: The Experiences of Non-governmental and Civil Society Organizations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, L. Encouraging covid vaccine uptake and safe behaviours-an uphill struggle against government complacency. BMJ 2021, 375, n2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeppe, J.; Cheadle, A.; Melton, M.; Faubion, T.; Miller, C.; Matthys, J.; Hsu, C. The Immunity Community: A Community Engagement Strategy for Reducing Vaccine Hesitancy. Health Promot. Pract. 2017, 18, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Attwell, K.; Hauck, Y.; Leask, J.; Omer, S.B.; Regan, A.; Danchin, M. Designing a multi-component intervention (P3-MumBubVax) to promote vaccination in antenatal care in Australia. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2021, 32, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollier, A.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Saad-Harfouche, F.G.; Widman, C.A.; Mahoney, M.C. HPV vaccination: Pilot study assessing characteristics of high and low performing primary care offices. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U.S.). How to Build COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in the Workplace. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/108253 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bocian, K.; Baryla, W.; Kulesza, W.M.; Schnall, S.; Wojciszke, B. The mere liking effect: Attitudinal influences on attributions of moral character. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, J.; Carlson, S.J.; Attwell, K.; Clark, K.K.; Kaufman, J.; Hughes, C.; Frawley, J.; Cashman, P.; Seal, H.; Wiley, K.; et al. Communicating with patients and the public about COVID-19 vaccine safety: Recommendations from the Collaboration on Social Science and Immunisation. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215, 9–12.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, J.; Kinnersley, P.; Jackson, C.; Cheater, F.; Bedford, H.; Rowles, G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: A framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, D.J.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Health literacy: Communication strategies to improve patient comprehension of cardiovascular health. Circulation 2009, 119, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berkhof, M.; van Rijssen, H.J.; Schellart, A.J.; Anema, J.R.; van der Beek, A.J. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: An overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, J.N.; Anshu Chhatwal, J.; Gupta, P.; Singh, T. Teaching and Assessing Communication Skills in Medical Undergraduate Training. Indian Pediatr. 2016, 53, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. COVID-19 Vaccine Roll-Out: 21 September 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/09/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-update-23-september-2022-this-presentation-delivered-on-23-september-2022-contains-an-update-to-australia-s-covid-19-vaccine-rollout_2.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Independent Pandemic Management Advisory Committee. Review of COVID-19 Communications in Victoria: September 2022; Independent Pandemic Management Advisory Committee: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2022.

- Jalloh, M.F.; Wilhelm, E.; Abad, N.; Prybylski, D. Mobilize to vaccinate: Lessons learned from social mobilization for immunization in low and middle-income countries. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeterdal, I.; Lewin, S.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Glenton, C.; Munabi-Babigumira, S. Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 19, CD010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Ames, H.; Bosch-Capblanch, X.; Cartier, Y.; Cliff, J.; Glenton, C.; Lewin, S.; Muloliwa, A.M.; Oku, A.; Oyo-Ita, A.; et al. The comprehensive ‘Communicate to Vaccinate’ taxonomy of communication interventions for childhood vaccination in routine and campaign contexts. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, J.; Tuckerman, J.; Danchin, M. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Can Australia reach the last 20 percent? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Gender | Role/s | Formal Champion? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Female | Nurse | No |

| 02 | Female | Pharmacist | Yes |

| 03 | Female | Community health/engagement officer | Yes |

| 04 | Female | Community health/engagement officer | No |

| 05 | Female | Community health/engagement officer | No |

| 06 | Female | Disability organization representative | Yes |

| 07 | Male | General practitioner | Yes |

| 08 | Female | Multicultural group representative | No |

| 09 | Female | Multicultural group representative | Yes |

| 10 | Female | Community health/engagement officer | Yes |

| 11 | Male | Community health/engagement officer and multicultural group representative | Yes |

| 12 | Female | General practitioner | Yes |

| Measure | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| How confident are you in your ability to talk about the risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccines? | ||

| More confident | 118 | 94% |

| About the same | 7 | 6% |

| Less confident | 0 | 0% |

| Missing | 0 | |

| How confident are you in your ability to find appropriate resources on COVID-19 vaccination information? | ||

| More confident | 112 | 90% |

| About the same | 12 | 10% |

| Less confident | 1 | 1% |

| Missing | 0 | |

| How likely are you to initiate a conversation about COVID-19 vaccines with a person who might be hesitant? | ||

| Very likely/likely | 116 | 94% |

| Neutral | 6 | 5% |

| Not very likely/not likely at all | 1 | 1% |

| Missing | 2 | |

| Please rate how satisfied you were with the following: | ||

| The information about vaccine safety and effectiveness | ||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 123 | 99% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 1 | 1% |

| Not at all/not very satisfied | 0 | 0% |

| Missing | 1 | |

| The strategies for discussing vaccines with a hesitant person | ||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 121 | 97% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 2 | 2% |

| Not at all/not very satisfied | 2 | 2% |

| Missing | 0 | |

| The example conversations (role play) | ||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 113 | 92% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 8 | 7% |

| Not at all/not very satisfied | 2 | 2% |

| Missing | 2 | |

| The question and answer sections of the session | ||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 122 | 98% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 2 | 2% |

| Not at all/not very satisfied | 0 | 0% |

| Missing | 1 | |

| The quality of the presenters | ||

| Satisfied/very satisfied | 123 | 100% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 0 | 0% |

| Not at all/not very satisfied | 0 | 0% |

| Missing | 2 | |

| How did you find the length of the session? | ||

| Too short | 1 | 1% |

| About the right length | 122 | 98% |

| Too long | 2 | 2% |

| Missing | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaufman, J.; Overmars, I.; Leask, J.; Seale, H.; Chisholm, M.; Hart, J.; Jenkins, K.; Danchin, M. Vaccine Champions Training Program: Empowering Community Leaders to Advocate for COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111893

Kaufman J, Overmars I, Leask J, Seale H, Chisholm M, Hart J, Jenkins K, Danchin M. Vaccine Champions Training Program: Empowering Community Leaders to Advocate for COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines. 2022; 10(11):1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111893

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaufman, Jessica, Isabella Overmars, Julie Leask, Holly Seale, Melanie Chisholm, Jade Hart, Kylie Jenkins, and Margie Danchin. 2022. "Vaccine Champions Training Program: Empowering Community Leaders to Advocate for COVID-19 Vaccines" Vaccines 10, no. 11: 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111893

APA StyleKaufman, J., Overmars, I., Leask, J., Seale, H., Chisholm, M., Hart, J., Jenkins, K., & Danchin, M. (2022). Vaccine Champions Training Program: Empowering Community Leaders to Advocate for COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines, 10(11), 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111893