Digital Media Exposure and Health Beliefs Influencing Influenza Vaccination Intentions: An Empirical Research in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research and Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

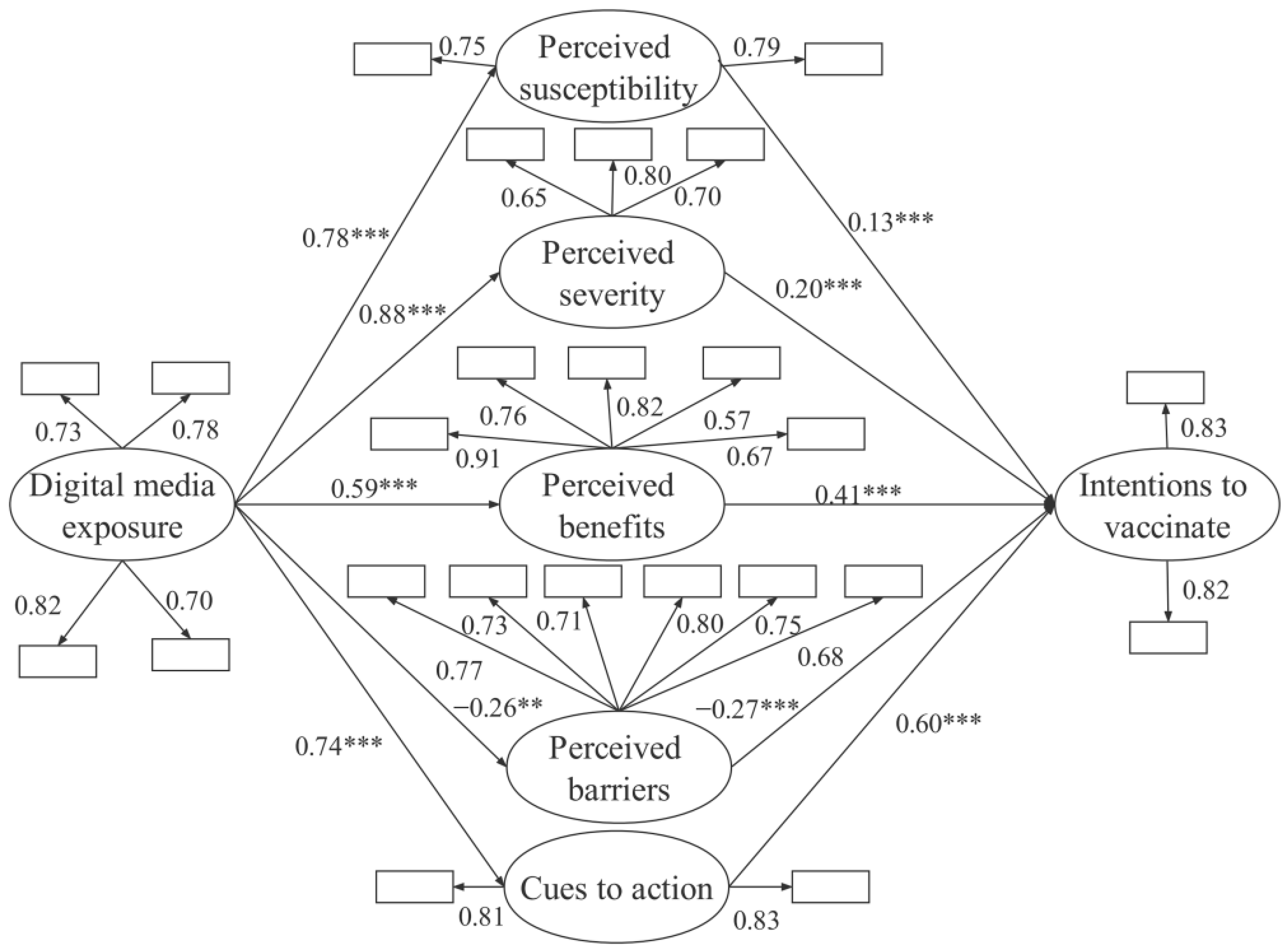

3.1. Factor Load Analysis & The Measurement Model

3.2. The Structural Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fall, E.; Izaute, M.; Chakroun-Baggioni, N. How can the health belief model and self-determination theory predict both influenza vaccination and vaccination intention? A longitudinal study among university students. Psychol. Health 2017, 33, 746–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichol, K.L.; Heilly, S.D.; Ehlinge, E. Colds and Influenza-Like Illnesses in University Students: Impact on Health, Academic and Work Performance, and Health Care Use. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.N.; Wu, P.; Peng, Z.B.; Wang, X.L.; Chen, T.; Wong, J.Y.T.; Yang, J.; Bond, H.S.; Wang, L.J.; et al. Influenza-associated excess respiratory mortality in China, 2010–2015: A population-based study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e473–e481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, Z.; Zhu, A.; Ren, M.; Geng, M.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Feng, L.; Peng, Z.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Mainland China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Harris, K.M. Perceived seriousness of seasonal and A(H1N1) influenzas, attitudes toward vaccination, and vaccine uptake among U.S. adults: Does the source of information matter? Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, C.E.; Riphagen-Dalhuisen, J.; Looijmans-van den Akker, I.; Frijstein, G.; Van der Geest-Blankert, A.D.J.; Danhof-Pont, M.B.; de Jager, H.J.; Bos, A.A.; Smeets, E.; de Vries, M.J.T.; et al. Determination of factors required to increase uptake of influenza vaccination among hospital-based healthcare workers. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, D. The Power of Social Media for HPV Vaccination–Not Fake News! Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2019, 39, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Health Information Sources and the Influenza Vaccination: The Mediating Roles of Perceived Vaccine Efficacy and Safety. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Akinwunmi, B.; Zhang, C.J.P.; Ming, W.K. The Impact of Public Health Events on COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Chinese Social Media: National Infoveillance Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e32936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, C.; Maietti, E.; Di Valerio, Z.; Montalti, M.; Fantini, M.P.; Gori, D. Vaccine hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination: Investigating the role of information sources through a mediation analysis. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2021, 13, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Riccio, M.; Bechini, A.; Buscemi, P.; Bonanni, P.; Working Group DHS; Boccalini, S. Reasons for the Intention to Refuse COVID-19 Vaccination and Their Association with Preferred Sources of Information in a Nationwide, Population-Based Sample in Italy, before COVID-19 Vaccines Roll Out. Vaccines 2022, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, M.A.; Brewer, N.T.; Shah, P.D.; Calo, W.A.; Gilkey, M.B. Stories about HPV vaccine in social media, traditional media, and conversations. Prev. Med. 2018, 118, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, P.H. Social media and COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy: Mediating role of the COVID-19 vaccine perception. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, C.; Graziano, G.; Bonaccorso, N.; Conforto, A.; Cimino, L.; Sciortino, M.; Mazzucco, W. Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Vaccination Acceptance/Hesitancy among the Community Pharmacists of Palermo’s Province, Italy: From Influenza to COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanasekaran, S.K.; Finkelstein, J.A.; Hohman, K.; O’Brien, M.; Kruskal, B.; Lieu, T.A. Parental Perspectives on Influenza Vaccination among Children with Asthma. Public Health Rep. 2006, 121, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.K.; Holland, M.L.; Bhattacharya, J.; Phelps, C.E.; Szilagyi, P.G. Effects of Mass Media Coverage on Timing and Annual Receipt of Influenza Vaccination among Medicare Elderly. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 45, 1287–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M.P.S.; Lam, F.L.Y.; Coker, R. Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in adults: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2016, 38, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Boggiano, V.; Nguyen, L.H.; Latkin, C.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, T.T.; Le, H.T.; Vu, T.T.M.; Ho, C.S.H.; Ho, R. Media representation of vaccine side effects and its impact on utilization of vaccination services in Vietnam. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1717–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, F. COVID-19 Vaccines on TikTok: A Big-Data Analysis of Entangled Discourses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, T.; Lin, F. The Digital Divide Is Aging: An Intergenerational Investigation of Social Media Engagement in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Liu, S. Understanding consumer health information-seeking behavior from the perspective of the risk perception attitude framework and social support in mobile social media websites. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 105, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.L.; Krupat, E.; Bell, R.A.; Kravitz, R.L.; Haidet, P. Beliefs about control in the physician-patient relationship. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DaCosta DiBonaventura, M.; Chapman, G.B. Moderators of the intention–behavior relationship in influenza vaccinations: Intention stability and unforeseen barriers. Psychol. Health 2005, 20, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. SAGE J. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.M.; Lau, J.T.; Ma, Y.L.; Lau, M.M. Prevalence and associated factors of seasonal influenza vaccination among 24- to 59-month-old children in Hong Kong. Vaccine 2015, 33, 3556–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue, C.L.; Valley, J. Predictors of Influenza Vaccine: Acceptance Among Healthy Adult Workers. AAOHN J. 2002, 50, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. China’s new demographic reality: Learning from the 2010 census. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2013, 39, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, M. Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Igbaria, M.; Guimaraes, T.; Davis, G.B. Testing the determinants of microcomputer usage via a structural equation model. J. Manage. Inform. Syst. 1995, 11, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The health belief model. Health Behav. Health Educ. 2008, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hollmeyer, H.G.; Hayden, F.; Poland, G.; Buchholz, U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals—A review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3935–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Chu, S.L.; Sickler, H.; Shaw, J.; Nadeau, J.A.; McNutt, L.-A. Low uptake of influenza vaccine among university students: Evaluating predictors beyond cost and safety concerns. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1659–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, M.; Pandya, P. Finding response times in a real-time system. Comput. J. 1986, 29, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Chen, A.; Cui, B.; Liao, W. Exploring public perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine online from a cultural perspective: Semantic network analysis of two social media platforms in the United States and China. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scognamiglio, F.; Fantini, M.P.; Reno, C.; Montalti, M.; Di Valerio, Z.; Soldà, G.; Salussolia, A.; la Fauci, G.; Capodici, A.; Gori, D. Vaccinations and Healthy Ageing: How to Rise to the Challenge Following a Life-Course Vaccination Approach. Vaccines 2022, 10, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietti, E.; Greco, M.; Reno, C.; Rallo, F.; Trerè, D.; Savoia, E.; Fantini, M.P.; Scheier, L.M.; Gori, D. Assessing the Role of Trust in Information Sources, Adoption of Preventive Practices, Volunteering and Degree of Training on Biological Risk Prevention, on Perceived Risk of Infection and Usage of Personal Protective Equipment Among Italian Medical Students During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 746387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Renkewitz, F.; Betsch, T.; Ulshöfer, C. The Influence of Vaccine-critical Websites on Perceiving Vaccination Risks. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Atkins, K.E.; Feng, L.Z.; Pang, M.F.; Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, X.X.; Cowling, B.J.; Yu, H.J. Seasonal influenza vaccination in China: Landscape of diverse regional reimbursement policy, and budget impact analysis. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5724–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Media Exposure | I have been exposed to information about the influenza vaccine on News websites/apps (Toutiao, Tengxun News, People’s Daily, etc.). | [21] |

| I have contact information about the influenza vaccine on SNS websites/apps (WeChat, Weibo, Xiaohongshu, etc.). | [21] | |

| I have contact information about the influenza vaccine on online community websites/apps (Douban, Zhihu, Tianya, etc.). | [21] | |

| I have been exposed to flu vaccines on online video websites/short video apps (Bilibili, Douyin, Kuaishou, etc.). | [21] | |

| Perceived susceptibility | I am worried about catching the flu in the fall and winter. | [1] |

| I think I am more likely to get the flu than other people. | [26] | |

| Perceived severity | The flu is a severe illness to me. | [1] |

| If I get the flu, it will seriously affect my daily life, work, or study. | [26] | |

| If I get the flu accidentally, it will be a health threat to the whole family. | [1] | |

| Perceived benefits | Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent influenza. | [26] |

| Vaccination can alleviate the symptoms after infection, even if it can’t wholly avoid infection with the influenza virus. | [6] | |

| Vaccination can avoid the possible loss of work, time, energy, and economy caused by influenza. | [31] | |

| Vaccination against influenza can avoid the risk of my family catching influenza because of me. | [1] | |

| Vaccination can reduce my fear of catching influenza and play a significant role in psychological comfort. | [1] | |

| Perceived barriers | The flu virus keeps mutating, and I doubt the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine. | [1] |

| Healthy people can also prevent influenza with proper daily protection, and vaccination is not necessary. | [32] | |

| Getting an influenza vaccine is not conducive to the establishment of immunity and resistance to influenza. | [26] | |

| Influenza is not a severe and life-threatening illness, and patients usually recover within one to two weeks. | [26] | |

| I don’t know “I need to be vaccinated against influenza.” | [31] | |

| I don’t know how to apply for influenza vaccination. | [31] | |

| Cues to action | I have received messages from social media urging everyone to get an influenza vaccine. | [1] |

| The bad news about the flu epidemic on social media also influenced my decision to influenza vaccination. | [15] | |

| Vaccination intentions | If conditions permit, I am willing to vaccinate against influenza. | [31] |

| If conditions permit, I will make a plan for influenza vaccination in the future. | [31] |

| Construct | Item | Loading | M | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital media exposure | DMP1 | 0.73 | 3.29 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| DMP2 | 0.78 | ||||||

| DMP3 | 0.82 | ||||||

| DMP4 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Perceived susceptibility | PS1 | 0.75 | 3.33 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.59 |

| PS2 | 0.79 | ||||||

| Perceived severity | PSR1 | 0.65 | 3.38 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.52 |

| PSR2 | 0.80 | ||||||

| PSR3 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Perceived benefits | PB1 | 0.91 | 3.59 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.57 |

| PB2 | 0.76 | ||||||

| PB3 | 0.82 | ||||||

| PB4 | 0.57 | ||||||

| PB5 | 0.67 | ||||||

| Perceived barriers | PBR1 | 0.77 | 3.32 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.55 |

| PBR2 | 0.73 | ||||||

| PBR3 | 0.71 | ||||||

| PBR4 | 0.80 | ||||||

| PBR5 | 0.75 | ||||||

| PBR6 | 0.68 | ||||||

| Cues to action | CTA1 | 0.81 | 3.42 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.67 |

| CTA2 | 0.83 | ||||||

| Intentions to vaccinate | ATV1 | 0.83 | 3.31 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.68 |

| ATV2 | 0.82 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Yin, H.; Guo, D. Digital Media Exposure and Health Beliefs Influencing Influenza Vaccination Intentions: An Empirical Research in China. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111913

Zhao Q, Yin H, Guo D. Digital Media Exposure and Health Beliefs Influencing Influenza Vaccination Intentions: An Empirical Research in China. Vaccines. 2022; 10(11):1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111913

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qingting, Hao Yin, and Difan Guo. 2022. "Digital Media Exposure and Health Beliefs Influencing Influenza Vaccination Intentions: An Empirical Research in China" Vaccines 10, no. 11: 1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111913

APA StyleZhao, Q., Yin, H., & Guo, D. (2022). Digital Media Exposure and Health Beliefs Influencing Influenza Vaccination Intentions: An Empirical Research in China. Vaccines, 10(11), 1913. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111913