Understanding the Role of Misinformation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Rural State

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

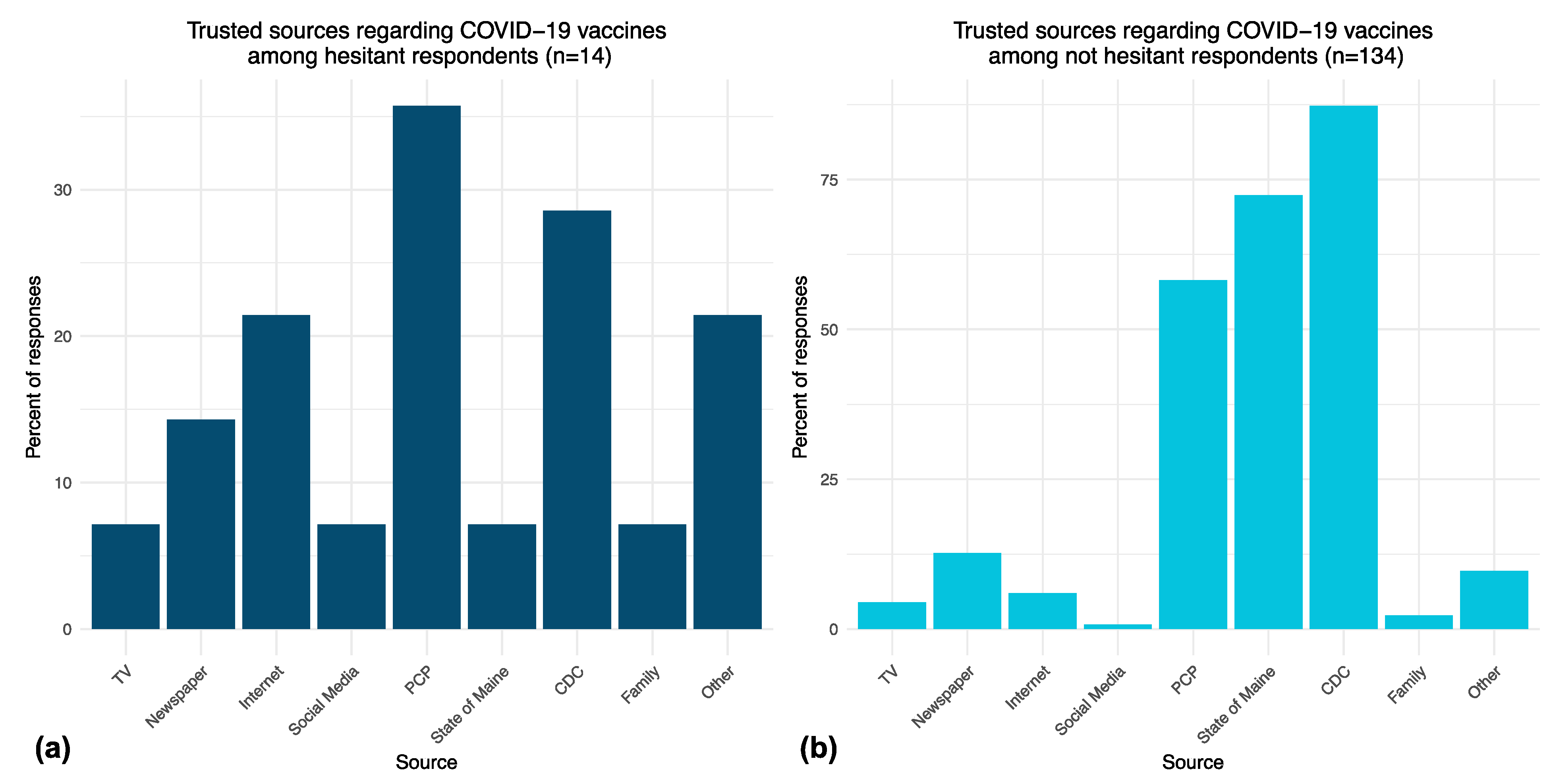

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Public Health Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker: United States COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Laboratory Testing (NAATs) by State, Territory, and Jurisdiction. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailydeaths (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Aschwanden, C. Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature 2021, 591, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, P.; Hartley, D.; Beck, A.F.; Oliver, G.H.; Sampath, B.; Roderick, T.; Miff, S. Rethinking Herd Immunity: Managing the Covid-19 Pandemic in a Dynamic Biological and Behavioral Environment. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.; Cho, H.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Bae, G.R.; Lee, S.G. Relationship between intention of novel influenza A (H1N1) vaccination and vaccination coverage rate. Vaccine 2010, 29, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.B.; Goodwin, R. Determinants of adults’ intention to vaccinate against pandemic swine flu. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khubchandani, J.; Sharma, S.; Price, J.H.; Wiblishauser, M.J.; Sharma, M.; Webb, F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors Associated with US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, S.R.; Eldredge, C.; Ersing, R.; Remington, C. Vaccine Hesitancy and Exposure to Misinformation: A Survey Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Fredricks, K.; Woc-Colburn, L.; Bottazzi, M.E.; Weatherhead, J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencin, C.T.; McClinton, A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call to Action to Identify and Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 7, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcendor, D.J. Targeting COVID Vaccine Hesitancy in Rural Communities in Tennessee: Implications for Extending the COVID-19 Pandemic in the South. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.J.; Pumkam, C.; Probst, J.C. Rural-urban differences in the location of influenza vaccine administration. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5970–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Bridges, C.B.; Euler, G.L.; Singleton, J.A. Influenza vaccination of recommended adult populations, U.S.; 1989–2005. Vaccine 2008, 26, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, M.; Maxwell, T.; Hill, S.; Patel, R.; Trower, J.; Wangui, L.; Truong, H.A. Exploring COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy at a rural historically black college and university. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogue, K.; Jensen, J.L.; Stancil, C.K.; Ferguson, D.G.; Hughes, S.J.; Mello, E.J.; Burgess, R.; Berges, B.K.; Quaye, A.; Poole, B.D. Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. Vaccines 2020, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. 2021. Available online: https://files.kff.org/attachment/TOPLINE-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-September-2021.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, P.; Dube, E. Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 era. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2020, 19, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Tyson, A. Growing Share of Americans Say They Plan to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine—Or Already Have. Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.; Paterson, P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razai, M.S.; Oakeshott, P.; Esmail, A.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Viswanath, K.; Mills, M.C. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The five Cs to tackle behavioural and sociodemographic factors. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, S.C.; Jamison, A.M.; An, J.; Hancock, G.R.; Freimuth, V.S. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: Results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine 2019, 37, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service. Urban Influence Codes. 2013. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Pietrobon, A.J.; Teixeira, F.M.E.; Sato, M.N. I mmunosenescence and Inflammaging: Risk Factors of Severe COVID-19 in Older People. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpman, M.; Zuckerman, S. Few Unvaccinated Adults Have Talked to Their Doctors about the COVID-19 Vaccines; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, N.E.; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total N (%) | Hesitant N (%) | Not Hesitant (N%) | Fisher Exact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | 148 | 14 | 134 | |

| Age Range | ||||

| 18 to 34 years | 26 (18%) | 3(21%) | 23(17%) | 0.01 |

| 35 to 54 years | 42 (28%) | 8(57%) | 34(25%) | |

| 55 to 64 years | 38 (26%) | 3(21%) | 35(26%) | |

| 65 and older years | 41 (28%) | 41(31%) | ||

| Unknown | 1(1%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 124 (84%) | 9(64%) | 115(86%) | 0.07 |

| Male | 19 (13%) | 4(29%) | 15(11%) | |

| Other or prefer not to answer | 5 (3%) | 1(7%) | 4(3%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 1.0 | |||

| White | 136 (92%) | 13(93%) | 123(92%) | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 3 (2%) | 3(2%) | ||

| Rurality (17 Counties) | ||||

| Metro | 76 (51%) | 4(29%) | 72(54%) | 0.09 |

| Non-Metro | 65 (44%) | 9(64%) | 56(42%) | |

| Education | 0.12 | |||

| High School Graduate or Less | 9 (6%) | 3(21%) | 6(4%) | |

| Some College | 19 (13%) | 2(14%) | 17(13%) | |

| Four Year Degree | 42 (28%) | 3(21%) | 39(29%) | |

| Post Graduate | 78 (53%) | 6(43%) | 72(54%) | |

| Political Affiliation | ||||

| Democrat | 88 (59%) | 88(66%) | <0.001 | |

| Republican | 13 (9%) | 2(14%) | 11(8%) | |

| Independent | 25 (17%) | 6(43%) | 19(14%) | |

| No Affiliation | 22 (15%) | 6(43%) | 16(12%) | |

| Vaccination Status | ||||

| Vaccinated or Plan to Be | 134 (84%) | |||

| Vaccine hesitant | 14 (9%) |

| Construct (5Cs) | Survey Category | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Source of Information | Info about Virus or Vaccine |

|

| Confidence Vaccine Plans | Vaccine Plans Self |

|

| Confidence | Family and Friend Vaccine Plans |

|

| Confidence Convenience | Concerns |

|

| Confidence | Type of Vaccine Matters |

|

| Complacency | Motivation |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hess, A.M.R.; Waters, C.T.; Jacobs, E.A.; Barton, K.L.; Fairfield, K.M. Understanding the Role of Misinformation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Rural State. Vaccines 2022, 10, 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050818

Hess AMR, Waters CT, Jacobs EA, Barton KL, Fairfield KM. Understanding the Role of Misinformation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Rural State. Vaccines. 2022; 10(5):818. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050818

Chicago/Turabian StyleHess, Ann Marie R., Colin T. Waters, Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Kerri L. Barton, and Kathleen M. Fairfield. 2022. "Understanding the Role of Misinformation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Rural State" Vaccines 10, no. 5: 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050818

APA StyleHess, A. M. R., Waters, C. T., Jacobs, E. A., Barton, K. L., & Fairfield, K. M. (2022). Understanding the Role of Misinformation in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Rural State. Vaccines, 10(5), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050818