Attitudes of Healthcare Workers in Israel towards the Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Study Tool

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Attitudes toward the Fourth COVID-19 Vaccine Dose (Second Booster)

3.3. Attitudes toward Vaccination of Children, Acceptance of a Hypothetical Yearly Booster Vaccine, and Reported Adverse Effects following a Prior COVID-19 Vaccination

3.4. Perception of the Risk and Benefit of the Fourth Dose Significantly Predict HCWs’ Willingness to Get the Fourth Dose of the COVID-19 Vaccine

4. Discussion

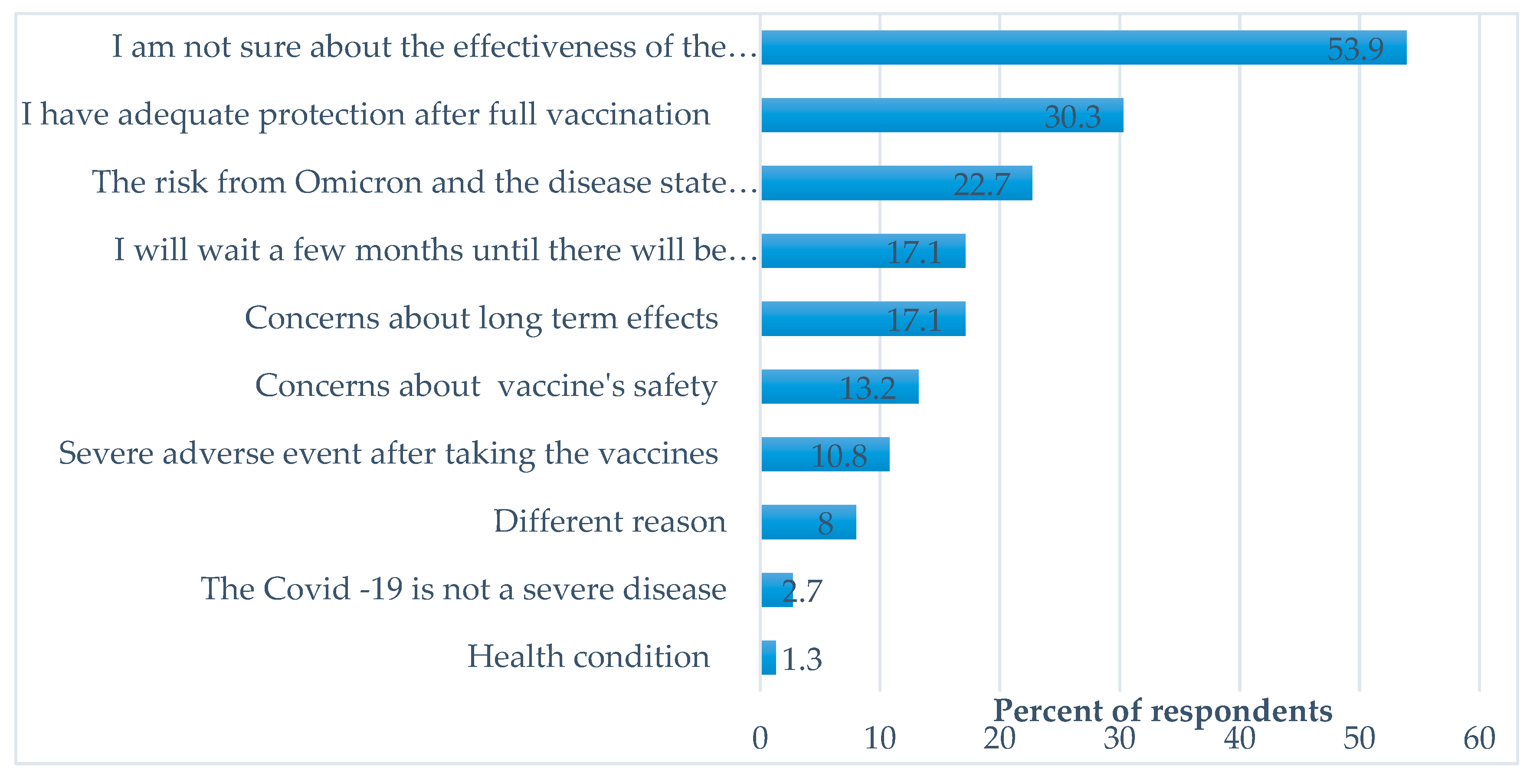

4.1. Reasons for Hesitation to Receive a Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine

4.2. Demographic Factors

4.3. Perceptions of the Fourth Dose

4.4. Trust, Willingness to Vaccinate Children, and the Acceptance of Hypothetical Yearly Booster Vaccine

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, N.A.; Al-Thani, H.; El-Menyar, A. The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variant (Omicron) and increasing calls for COVID-19 vaccine boosters-The debate continues. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 45, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Israeli, A. Israel’s rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A. A Picture of the Nation. Israel’s Society and Economy in Figures; Taub Center for Social Policy Studies: Israel, Jerusalem, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clarfield, A.M.; Manor, O.; Nun, G.B.; Shvarts, S.; Azzam, Z.S.; Afek, A.; Basis, F.; Israeli, A. Health and health care in Israel: An introduction. Lancet 2017, 389, 2503–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Israeli, A.; Hartal, M.; Davidovitch, N. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and access barriers to achieve persistent progress in Israel’s COVID-19 vaccination program. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Margalit, R.; Strahilevitz, J.; Paltiel, O. Questioning the justification for a fourth SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbel, R.; Sergienko, R.; Friger, M.; Peretz, A.; Beckenstein, T.; Yaron, S.; Netzer, D.; Hammerman, A. Effectiveness of a second BNT162b2 booster vaccine against hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in adults aged over 60 years. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1486–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) Statement on COVID-19 Vaccinations in 2022. 21 February 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation-statement-on-covid-19-vaccinations-in-2022/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation-jcvi-statement-on-covid-19-vaccinations-in-2022-21-february-2022 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Second Booster Dose of Two COVID-19 Vaccines for Older and Immunocompromised Individuals; Food and Drug Administration: Sillver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

- COVID-19 Tracker. Available online: https://datadashboard.health.gov.il/COVID-19/general (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- WHO. World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Aw, J.; Seng, J.J.B.; Seah, S.S.Y.; Low, L.L. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy-A Scoping Review of Literature in High-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, C.S.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Mirza, M.S.; Chaudhry, B.; Khan, S.J. Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Systematic Review of Associated Social and Behavioral Factors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; Eguchi, A.; Yoneoka, D.; Kawashima, T.; Tanoue, Y.; Murakami, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Maruyama-Sakurai, K.; Gilmour, S.; Shi, S.; et al. Reasons for being unsure or unwilling regarding intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Japanese people: A large cross-sectional national survey. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 14, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velan, B. Vaccine hesitancy as self-determination: An Israeli perspective. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2016, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutman, A.; Yoeli, N. Influenza vaccination motivators among healthcare personnel in a large acute care hospital in Israel. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2016, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebmann, T.; Wright, K.S.; Anthony, J.; Knaup, R.C.; Peters, E.B. Seasonal influenza vaccine compliance among hospital-based and nonhospital-based healthcare workers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2012, 33, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Badarna Keywan, H. Physicians’ Perspective on Vaccine-Hesitancy at the Beginning of Israel’s COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign and Public’s Perceptions of Physicians’ Knowledge When Recommending the Vaccine to Their Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 855468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.J.; Lee, B.; Nugent, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers-A Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babicki, M.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. Attitudes of Poles towards the COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Dose: An Online Survey in Poland. Vaccines 2022, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klugar, M.; Riad, A.; Mohanan, L.; Pokorná, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Hesitancy (VBH) of Healthcare Workers in Czechia: National Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Shekhar, R.; Kottewar, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Pathak, D.; Kapuria, D.; Barrett, E.; Sheikh, A.B. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Attitude toward Booster Doses among US Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramot, S.; Tal, O. Attitudes of healthcare workers and members of the public toward the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur-Arie, R.; Davidovitch, N.; Rosenthal, A. Intervention hesitancy among healthcare personnel: Conceptualizing beyond vaccine hesitancy. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 2022, 40, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Palaian, S.; Shankar, P.R.; Subedi, N. Risk Perception and Hesitancy Toward COVID-19 Vaccination Among Healthcare Workers and Staff at a Medical College in Nepal. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrissian, A.A.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Patel, P.; Lawrence Beeson, W.; Loo, L.K.; Tavakoli, S.; Dubov, A. Impact of COVID-19 vaccine-associated side effects on health care worker absenteeism and future booster vaccination. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3174–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Variant of the Virus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fvariants%2Fomicron-variant.html (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- WHO. Statement for Healthcare Professionals: How COVID-19 Vaccines Are Regulated for Safety and Effectiveness (Revised March 2022). Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-05-2022-statement-for-healthcare-professionals-how-covid-19-vaccines-are-regulated-for-safety-and-effectiveness (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Spinewine, A.; Pétein, C.; Evrard, P.; Vastrade, C.; Laurent, C.; Delaere, B.; Henrard, S. Attitudes towards COVID-19 Vaccination among Hospital Staff-Understanding What Matters to Hesitant People. Vaccines 2021, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Poniedziałek, B.; Fal, A. Willingness to Receive the Booster COVID-19 Vaccine Dose in Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Vallières, F.; Bentall, R.P.; Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.; Mason, L.; Gibson-Miller, J.; et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D.; Shao, L.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Intention to COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth-Manikowski, S.M.; Swirsky, E.S.; Gandhi, R.; Piscitello, G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Wang, R.; Tao, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Acceptance of a Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine and Associated Factors in China Based on Health Belief Model: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.B.; Fried, R.L.; Cochran, P.; Eichelberger, L.P. Evolving perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines among remote Alaskan communities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2022, 81, 2021684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-Y.S.; Burgdorf, C.E.; Gaysynsky, A.; Hunter, C.M. COVID-19 Vaccination Communication: Applying Behavioral and Social Science to Address Vaccine Hesitancy and Foster Vaccine Confidence; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020.

- Batra, K.; Sharma, M.; Dai, C.L.; Khubchandani, J. COVID-19 Booster Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Multi-Theory-Model (MTM)-Based National Assessment. Vaccines 2022, 10, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.P.S.; Feng, S.; Janani, L.; Cornelius, V.; Aley, P.K.; Babbage, G.; Baxter, D.; Bula, M.; Cathie, K.; Chatterjee, K.; et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines given as fourth-dose boosters following two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2 and a third dose of BNT162b2 (COV-BOOST): A multicentre, blinded, phase 2, randomised trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubet, P.; Launay, O. What a second booster dose of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines tells us. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1092–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Goldberg, Y.; Mandel, M.; Bodenheimer, O.; Amir, O.; Freedman, L.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Ash, N.; Huppert, A.; Milo, R. Protection by a Fourth Dose of BNT162b2 against Omicron in Israel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.W.C.; Tan, H.M.; Lee, W.H.; Mathews, J.; Young, D. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers: A Retrospective Observational Study in Singapore. Vaccines 2022, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limiñana-Gras, R.M.; Sánchez-López, M.P.; Saavedra-San Román, A.I.; Corbalán-Berná, F.J. Health and gender in female-dominated occupations: The case of male nurses. J. Men’s Stud. 2013, 21, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at A Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heyerdahl, L.W.; Dielen, S.; Nguyen, T.; Van Riet, C.; Kattumana, T.; Simas, C.; Vandaele, N.; Vandamme, A.M.; Vandermeulen, C.; Giles-Vernick, T.; et al. Doubt at the core: Unspoken vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 12, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Walter, N.; Green, M.S. Health care workers--part of the system or part of the public? Ambivalent risk perception in health care workers. Am. J. Infect. Control 2014, 42, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | NegP4D N = 76 | Vaccinated N = 48 | All N = 124 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 36.3 (7.35) | 38.5 (8.35) | 37.18(7.8) | 0.129 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.022 | |||

| Male | 22 (47.8%) | 24 (54.2%) | 46 (37.09%) | |

| Female | 54 (69.2%) | 24 (30.8%) | 78 (62.9%) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.118 | |||

| Married/living with a partner | 57 (59.4%) | 39 (40%) | 96 (77.4%) | |

| Single | 18 (75%) | 6 (25%) | 24 (19.4%) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 4 (3.22%) | |

| Number of children, mean (SD) | 1.68 (1.87) | 1.64 (1.57) | 1.66 (1.75) | 0.906 |

| * Profession | 0.046 | |||

| Physician | 41 (53.9%) | 35 (46.1%) | 76 (61.8%) | |

| Nurse | 15 (83.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 18 (14.6%) | |

| Other healthcare professional | 20 (69%) | 9 (31%) | 29 (23.6%) | |

| Perceived health status *, mean (SD) | 9.08 (1.2) | 8.72 (1.5) | 8.94 (1.35) | 0.153 |

| Undergoes screening tests regularly **, mean (SD) | 6.3 (2.8) | 6 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.8) | 0.662 |

| COVID-19 vaccination history, n (%) | ||||

| 1 + 2 dose only | 10 (83.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 12 (9.7 %) | 0.123 |

| 1 + 2 + 3 doses | 64 (58.2%) | 46 (41.8%) | 110 (88.7%) | |

| Engaged in research **, mean (SD) | 4.21 (2.94) | 4.09 (2.59) | 4.16 (2.8) | 0.815 |

| Scale | NegP4D N = 76 Mean (SD) | Vaccinated N = 48 Mean (SD) | All N = 124 Mean (SD) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perception of using the fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose | 1–10 | 4.2 (2.7) | 2.2 (1.5) | 3.4 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Perceived benefit | 1–10 | 3.7(1.9) | 6.2 (2.1) | 4.7 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Subjective knowledge | 1–10 | 3.9(2.5) | 5.1(2.7) | 4.4 (2.6) | 0.014 |

| Novelty of health risk | 1–10 | 3.8(2.4) | 4.9(2.6) | 4.2 (2.5) | 0.014 |

| Severity of health risk involved with being vaccinated with the fourth dose | 1–10 | 4.3(2.3) | 2.6(1.3) | 3.6 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Perceived extent of knowledge that science has about the safety of the fourth dose | 1–10 | 4.1 (2.2) | 5.4 (2.5) | 4.6 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Booster safety | 1–10 | 5.8 (2.6) | 8.1 (1.8) | 6.7 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Booster effectiveness Protection from severe illness | 1–10 1–10 | 4.3 (2.5) 5.4 (2.6) | 5.8 (2.3) 7.6 (2) | 4.9 (2.5) 6.2 (2.6) | 0.001 <0.001 |

| More advantages than disadvantages Trust in the Ministry of Health | 1–10 1–10 | 4 (2.1) 4.1(2.4) | 7.7 (1.7) 6.9(2.3) | 5.4 (2.7) 5.2 (2.7) | <0.001 <0.001 |

| Trust in doctors Freedom of choice | 1–10 1–10 | 4.57 (2.5) 7.67 (3) | 7.7 (1.9) 6.02 (3.3) | 5.7 (2.8) 7 (3.2) | <0.001 0.005 |

Variable | b(se) | Model 1 OR [95% CI] | b(se) | Model 2 OR [95% CI] | b(se) | Model 3 OR [95% CI] | b(se) | Model 4 OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.58(0.45) | 1.79 [0.73, 4.36] | 0.59 (0.45) | 1.80 [0.73, 4.43] | 0.55 (0.56) | 1.74 [0.58, 5.23] | 0.3 (0.57) | 1.35 [0.43, 4.16] |

| Profession doctor | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Profession nurse (Ref. doctor) | −1.12 (0.7) | 0.32 [0.08, 1.29] | −1.10 (0.70) | 0.33 [0.08, 1.33] | −0.80 (0.83) | 0.44 [0.08, 2.27] | −0.56 (0.84) | 0.56 [0.11, 2.95] |

| Profession health care (Ref. doctor) | −0.25 (0.53) | 0.77 [0.27, 2.21] | −0.15 (0.54) | 0.86 [0.29, 2.50] | −0.22 (0.72) | 0.79 [0.19, 3.29] | −0.135 (0.78) | 0.87 [0.18, 4.03] |

| Health Related | ||||||||

| Prior COVID-19 vaccination | 1.17 (0.81) | 3.23 [0.65, 16.04] | 1.92 (1.16) | 6.82 [0.69, 66.849] | 1.93 (1.22) | 6.91 [0.62, 76.2] | ||

| Perceptions | ||||||||

| Total benefit | 0.95 (0.18) | 2.58 [1.81, 3.69]* | 0.84 (0.18) | 2.33 [1.62, 3.36] * | ||||

| Total risk | −0.47 (0.19) | 0.62 [0.43, 0.90] ** | ||||||

| Constant | −0.49 (0.35) | 0.612 | −1.60 (0.86) | 0.20 | −7.61 (1.76) | 0.00 | −5.51 (1.87) | 0.004 * |

| Model χ2 | 7.4 | 9.90 | 59.34, p < 0.001 | 66.57, p < 0.01 | ||||

| Step χ2 | 7.42 | 2.47 | 49.44, p < 0.001 | 7.22, p < 0.01 | ||||

| Naglekerke R2 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramot, S.; Tal, O. Attitudes of Healthcare Workers in Israel towards the Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines 2023, 11, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020385

Ramot S, Tal O. Attitudes of Healthcare Workers in Israel towards the Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines. 2023; 11(2):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020385

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamot, Shira, and Orna Tal. 2023. "Attitudes of Healthcare Workers in Israel towards the Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine" Vaccines 11, no. 2: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020385

APA StyleRamot, S., & Tal, O. (2023). Attitudes of Healthcare Workers in Israel towards the Fourth Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines, 11(2), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020385