Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

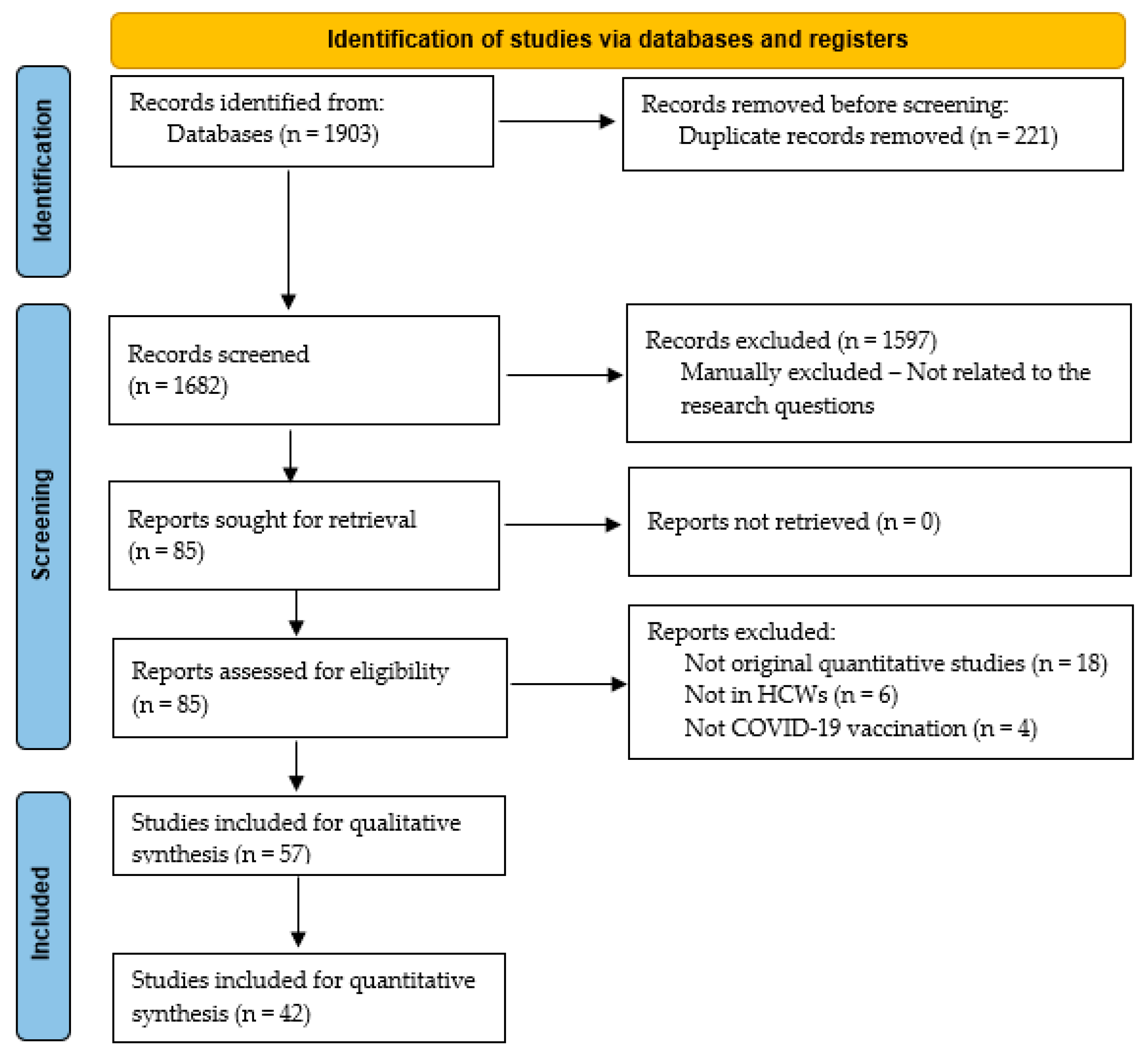

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Population: For this review, HCWs were defined as active professionals from all health-related professions (physicians, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, healthcare students, healthcare administration staff, etc.), with any vaccination status against COVID-19.

- Study design: Original quantitative studies were included.

- Outcomes: Articles that investigated the views and attitudes of HCWs towards mandatory COVID-19 vaccines of any type were included in this systematic review.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Population: Non HCW populations were not eligible for this systematic review. In addition, studies on retired HCWs did not meet the eligibility criteria.

- Study design: Studies of qualitative design were excluded.

- Outcomes: Studies that did not analyze data on HCWs’ views and attitudes towards mandatory COVID-19 vaccines of any type were not included.

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Individual Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Sub-Group Analysis

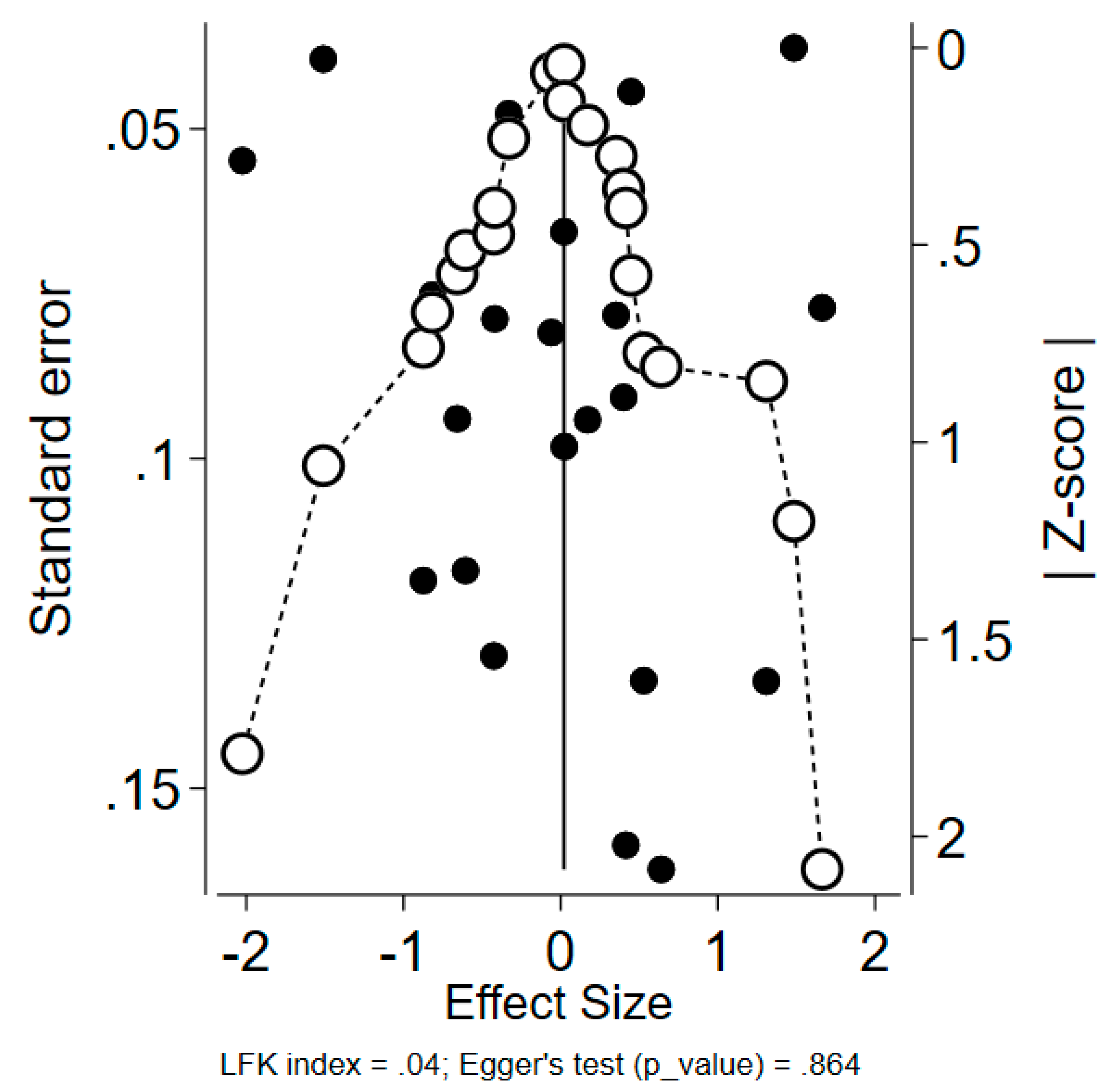

2.5. Publication Bias Risk Assessment

3. Results

3.1. HCWs’ Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Mandates for the General Population

3.1.1. Main Findings

3.1.2. Meta-Analysis

3.2. HCWs’ Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Mandates for HCWs

3.2.1. Main Findings

3.2.2. Meta-Analysis

3.3. Sub-Group and Sensitivity Analysis

3.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis and Comparison of the Meta-Analysis Results

3.3.2. Sub-Group Analysis

Sub-Group Analysis by W.H.O. Region

By Year of Publication

By Occupational Status (Physicians and Other HCWs)

3.4. Main Findings of the Studies Not Included in Quantitative Synthesis of Evidence

3.4.1. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates as a Working Requirement

3.4.2. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates for Hesitant HCWs

3.4.3. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandate Acceptance/Agreement

| Study | Country | Participants | Gender (Female) | Age (Years) | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [73] | Jordan | n = 287 | 190 (66.2%) | mean: 26.8 ± 8.9 (SD) | Medical field workers |

| [74] | Saudi Arabia | n = 529 | 362 (68%) | - | Physicians: 88 (16.64%) Nurses: 223 (42.16%) Administrators: 41 (7.75%) Allied health professionals: 23 (4.35%) EMS: 1 (0.19%) Pharmacists: 16 (3.02%) Technicians: 28 (5.29%) Other: 109 (20.60%) |

| [84] | Oman | n = 346 | 156 (45%) | Male, mean age ± SD: 46.8 ± 9.2 Female, mean age ± SD: 40.3 ± 7.6 | Physicians: 165 (47.7%) Nurses: 181 (52.3%) |

| [80] | Italy | n = 244 | Female: 163 (68.2%) Male: 70 (29.3%) No answer: 6 (2.5%) | 22.3 years (range 19–35) | Medical Students |

| [77] | Italy | n = 1450 | 939 (64.7%) | Mean age: 46.3 ± 15.7 (SD) | Pharmacists: 1450 (100%) |

| [70] | USA | n = 12,875 | 9358 (73%) | 18–29: 2305 (18%) 30–49: 5750 (45%) 50–64: 3744 (29%) 65+: 919 (8%) | Healthcare personnel |

| [79] | Poland | n = 497 | - | median (Q1–Q3) age was 24 (21–28) | Non-medical staff: 8 (1.6%) Other medical staff: 14 (2.8%) Students: 333 (67.1%) Nurses: 108 (21.7%) Midwives: 19 (3.8%) Paramedics: 2 (0.4%) Doctors: 13 (2.6%) |

| [81] | Greece | n = 1591 | 1004 (63%) | < 30: 282 (17.7%) 31–40: 363 (22.8%) 41–50: 450 (28.3%) > 50: 496 (31.2%) | Physicians: 480 (31.6%) Nursing personnel: 607 (39.9%) Paramedical personnel: 171 (11.2%) Supportive personnel: 72 (4.7%), Administrative personnel: 191 (12.6%) |

| [78] | Pakistan | n = 331 | 175 (53%) | <30: 183 (55%) 30–40: 93 (28%) 41–50: 26 (8%) 50–60: 22 (7%) >60: 7 (2%) | Physicians: 94 (28%) Nurse/nursing assistants: 95 (29%) Technologists/technicians: 118 (36%) Medical social officers: 24 (7%) |

| [71] | Nigeria | n = 440 | 224 (50.9%) | <25: 296 (67.3%) >25: 144 (32.7%) | Doctors of medicine: 166 (37.7%) Pharmacy staff: 133 (30.2%) Nursing staff: 103 (23.4%) Others: 38 (8.6%) |

| [72] | USA | n = 1506 | 77.1% | 44.1 ± 13.3 | Radiology department employees: 1506 (100%) |

| [76] | Switzerland | n = 776 | Female: 651 (84%) Male: 102 (13%) Missing information: 23 (3%) | - | Nurses: 332 (43%) Auxiliary nursing staff: 34 (4%) Patient care technicians: 4 (1%) Administration staff: 95 (12%) Respiratory, physical, or speech therapist: 55 (7%) Social workers: 2 (0%) Other: 24 (3%) Missing information: 22 (3%) |

| [83] | Arab Countries | n = 5708 | 2537 (44.4%) | 30.6 years (±10) | HCWs |

| [64] | Mongolia | n = 238 | 195 (81.9%) | 18–25: 18 (7.6%) 26–35: 148 (62.2%) 36–45: 48 (20.2%) 46–55: 20 (8.4%) >55: 4 (1.7%) | Physicians: 162 (68.1%) Other: 76 (31.9%) |

| [82] | Slovakia | n = 1124 | 997 (78.1%) | mean age: 48.3 ± 12.6 (SD) | Physicians: 582 (52%) Non-physician HCWs: 542 (48%) |

| [75] | China | n = 618 | 581 | - | Physicians: 322 (55%) Nurses/midwives: 235 (40%) Laboratory staff and others: 61 (5%) |

| Study | Country | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| [73] | Jordan | Factors affecting the willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19; 25.4% answered: mandatory in schools, universities, and workplaces |

| [74] | Saudi Arabia | Vaccine mandates decreased the OR of vaccine acceptance by 27% |

| [84] | Oman | Male and older HCWS had a more supportive stance towards mandatory COVID-19 vaccination when compared to their female and younger counterparts |

| [80] | Italy | Healthcare students believed that COVID-19 vaccine mandates should be compulsory for the whole population, including students. Furthermore, the participants stated that students who refuse COVID-19 vaccination should be excluded from university (8–10 (Likert-type answers medians)) |

| [77] | Italy | A total of 64.3% of those who changed their opinion regarding COVID-19 vaccination did so due to vaccines mandates |

| [79] | Poland | Most of the participants agreed that COVID-19 vaccines should be mandatory for HCWs (median: 4, Q3–5) |

| [81] | Greece | HCWs who supported COVID-19 vaccine mandates for HCWs were more prone to being vaccinated (83.9%) against COVID-19 when compared to those who did not support COVID-19 vaccine mandates (19%) for HCWs |

| [78] | Pakistan | A total of 59% of the participants answered that official requirements were their reason for being vaccinated |

| [72] | USA | The majority of HCWs showed compliance with vaccine mandates. Almost no disruption in the operation capacity of healthcare settings was shown |

| [76] | Switzerland | Reasons that may change participants’ minds regarding COVID-19 vaccination: mandatory vaccination for certain situations (e.g., travel) (11/79 (14%)) |

| [70] | USA | A total of 90.5% of HCWs who faced working requirements had been vaccinated against COVID-19, as compared to 73.3% of HCWs without vaccination requirements (24% increased odds) |

| [71] | Nigeria | A total of 52.3% would undergo COVID-19 vaccination if mandated by the heads of institution |

| [83] | Arab-speaking HCWs | Only 16.2% of HCWs supported mandating the vaccine in some groups of people |

| [64] | Mongolia | A total of 95.8% of HCWs agreed with vaccine mandates as a working requirement |

| [82] | Slovakia | Profession (being a physician) or/and vaccination status (being vaccinated) were important factors in the acceptance of vaccine mandates |

| [75] | China | A total of 2% of vaccinated HCWs were unwilling to be vaccinated but followed the employers’ mandates |

4. Discussion

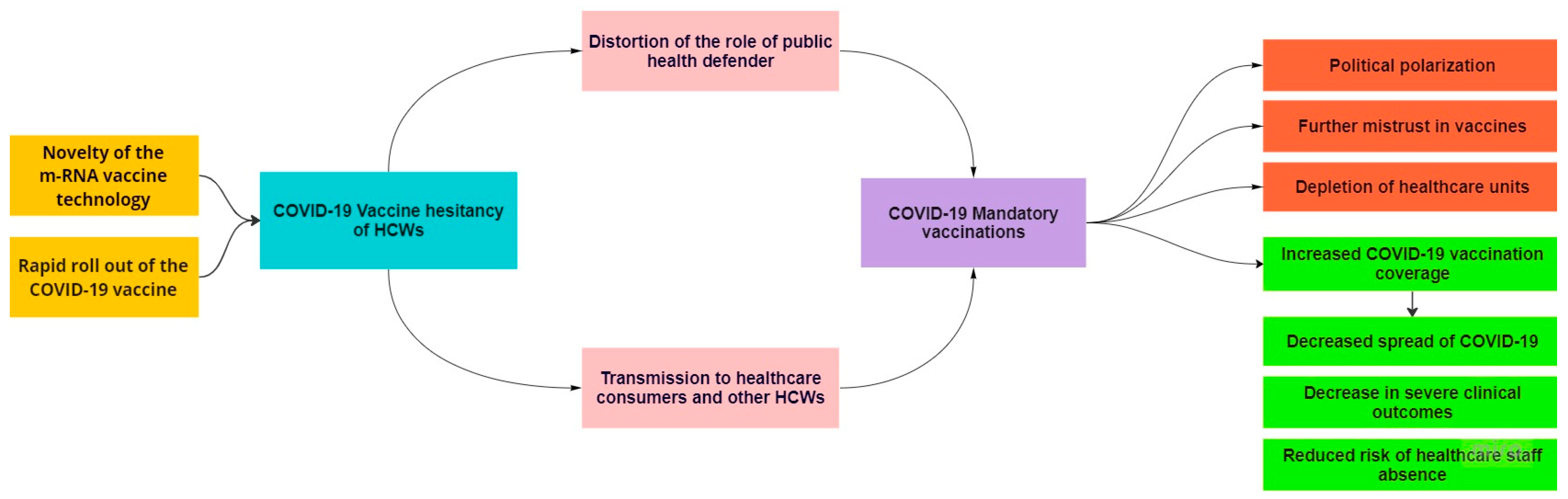

4.1. Origins of Controversy Regarding COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates

4.2. HCWs’ Moral Imperatives Regarding Vaccinations

4.3. The Relationship between COVID-19 Vaccination Status and/or Intention to Vaccinate against COVID-19 and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates

4.4. Other Vaccine Mandates

4.5. The Role of Top-Down Policies and Public Engagement

4.6. Societal Impacts of COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates

4.7. Novel Scientific Evidence during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.8. HCWs’ Attitude Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.9. Occupational Status and Acceptance of Vaccine Mandates

4.10. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Policy Implications and Recommendations

- Overall, 50% of HCWs opposed mandatory vaccination of the general population, and 36% of them opposed vaccine mandates for HCWs. These figures indicate that the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination of HCWs and the general population is a highly controversial topic among HCWs. In line with the W.H.O.s’ recommendations, our findings suggest that policy makers should prioritize other alternatives (e.g., information campaigns) over mandatory vaccination policies.

- We recognize the well-intentioned efforts of researchers to contribute to the scientific literature during emerging situations. In this context, policymakers should think critically before translating new evidence into policies, as our findings show that low-quality evidence with intriguing results tends to be published.

5.2. Suggestions for Future Research

- Further research is needed on the roles of different healthcare professionals regarding acceptance towards COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

- Understanding the relationship between vaccination status and/or intention to be vaccinated and the acceptance of vaccine mandates is expected to provide useful evidence for future vaccination policies.

- Our findings indicate that HCWs’ attitudes towards COVID-19 mandates may have changed during the pandemic. Determining the reasons for this change will inform policy makers as to the appropriate time of decision making.

- Important societal benefits are expected to arise as a result of clarifying the complex interactions between the different types of policy implementation and the role of the public engagement in the decision-making process during an epidemic/pandemic.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- COVID-19 and Mandatory Vaccination: Ethical Considerations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policybrief-Mandatory-vaccination-2022.1 (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Rimmer, A. COVID vaccination to be mandatory for NHS staff in England from spring 2022. BMJ 2021, 375, n2733. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n2733 (accessed on 16 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, G. COVID-19: How prepared is England’s NHS for mandatory vaccination? BMJ 2022, 376, o192. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/376/bmj.o192.full.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J. COVID-19: France and Greece make vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 374, n1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterlini, M. COVID-19: Italy makes vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 373, n905. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/373/bmj.n905.full.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, K.; Forman, R.; Mossialos, E.; Ndebele, P.; Hyder, A.A.; Nasir, K. COVID-19 vaccine mandate for healthcare workers in the United States: A social justice policy. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 21, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.J.; Lee, B.; Nugent, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers—A Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozek, L.S.; Jones, P.; Menon, A.R.; Hicken, A.; Apsley, S.; King, E.J. Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy in the Context of COVID-19: The Role of Trust and Confidence in a Seventeen-Country Survey. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 636255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeta, B.; Mulugeta, T.; Mamo, G.; Alemu, S.; Berhanu, N.; Milkessa, G.; Mengistu, B.; Melaku, T. An analysis of COVID-19 information sources. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özüdoğru, O.; Acer, Ö.; Bahçe, Y.G. Risks of catching COVID-19 according to vaccination status of healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant dominant period and their clinical characteristics. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3706–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulescu, J. Good reasons to vaccinate: Mandatory or payment for risk? J. Med. Ethics 2021, 47, 78–85. Available online: https://jme.bmj.com/content/47/2/78 (accessed on 4 February 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaivanov, A.; Kim, D.; Lu, S.E.; Shigeoka, H. COVID-19 vaccination mandates and vaccine uptake. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giubilini, A.; Savulescu, J.; Pugh, J.; Wilkinson, D. Vaccine mandates for healthcare workers beyond COVID-19. J. Med. Ethic. 2022, 49, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K.; de Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandatory Vaccinations for Health and Social Care Workers: Nuffield Council on Bioethics Urges Government to Gather More Evidence and Explore Other Options More Thoroughly before Introducing Coercive Measures; The Nuffield Council on Bioethics: London, UK. Available online: https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/news/mandatory-vaccinations-for-health-and-social-care-workers-nuffieldcouncil-on-bioethics-urges-government-to-gather-more-evidence-and-explore-other-options-more-thoroughlybefore-introducing-coercive-measures (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loney, P.L.; Chambers, L.W.; Bennett, K.J.; Roberts, J.G.; Stratford, P.W. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: Prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis. Can. 1998, 19, 170–176. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10029513/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Ryan, R. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: Data Synthesis and Analysis; Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; Available online: http://cccrg.cochrane.org (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17; StataCorp LLC.: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; Harris, R.; Bradburn, M.; Deeks, J.; Harbord, R.; Altman, D.; Steichen, T.; Sterne, J.; Higgins, J. METAN: Stata Module for Fixed and Random Effects Meta-Analysis; Statistical Software Components S456798; Boston College Department of Economics: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane.org. Chapter 10: Analysing Data and Undertaking Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Schwarzer, G.; Rücker, G. Meta-Analysis of Proportions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2345, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data Extraction for Ordinal Outcomes [Internet]. Cochrane.org. Available online: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_7/7_7_4_data_extraction_for_ordinal_outcomes.htm (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Barker, T.H.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Falavigna, M.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.P.; Saratzis, A.; Sutton, A.J.; Boucher, R.H.; Sayers, R.D.; Bown, M.J. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Barendregt, J.J.; Doi, S.A. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. Int. J. Evid.-Based Health 2018, 16, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, A.M.N.; Alshareef, N.; Alsharqi, O.; Al Rahahleh, N.; Chirwa, G.C.; Al-Hanawi, M.K. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vac-cine Among Healthcare Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 644300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noushad, M.; Nassani, M.Z.; Alsalhani, A.B.; Koppolu, P.; Niazi, F.H.; Samran, A.; Rastam, S.; Alqerban, A.; Barakat, A.; Almoallim, H.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Intention among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temsah, M.-H.; Aljamaan, F.; Alenezi, S.; Alhasan, K.; Alrabiaah, A.; Assiri, R.; Bassrawi, R.; Alhaboob, A.; Alshahrani, F.; Alarabi, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant: Exploring Healthcare Workers’ Awareness and Perception of Vaccine Effectiveness: A National Survey During the First Week of WHO Variant Alert. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 878159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldosary, A.H.; Alayed, G.H. Willingness to vaccinate against Novel COVID-19 and contributing factors for the acceptance among nurses in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 6386–6396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giannakou, K.; Kyprianidou, M.; Christofi, M.; Kalatzis, A.; Fakonti, G. Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination for Healthcare Professionals and Its Association With General Vaccination Knowledge: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey in Cyprus. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 897526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncel, S.; Alvur, M.; Çakıcı, Ö. Turkish Healthcare Workers’ Personal and Parental Attitudes to COVID-19 Vaccination From a Role Modeling Perspective. Cureus 2022, 14, e22555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurttas, B.; Poyraz, B.C.; Sut, N.; Ozdede, A.; Oztas, M.; Uğurlu, S.; Tabak, F.; Hamuryudan, V.; Seyahi, E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among pa-tients with rheumatic diseases, healthcare workers and general population in Turkey: A web-based survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gönüllü, E.; Soysal, A.; Atıcı, S.; Engin, M.; Yeşilbaş, O.; Kasap, T.; Fedakar, A.; Bilgiç, E.; Tavil, E.B.; Tutak, E.; et al. Pediatricians’ COVID-19 experiences and views on the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional survey in Turkey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2389–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Maillard, A.; Bodelet, C.; Claudel, A.-L.; Gaillat, J.; Delory, T.; on behalf of the ACV Alpin Study Group. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Multi-Centric Survey in France. Vaccines 2021, 9, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, K.; Gogoi, M.; Martin, C.A.; Papineni, P.; Lagrata, S.; Nellums, L.B.; McManus, I.C.; Guyatt, A.L.; Melbourne, C.; Bryant, L.; et al. workers’ views on mandatory SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the UK: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods analysis from the UK-REACH study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, A.-K.; Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Eitenberger, M.; Gabriel, M.; Klager, E.; Kletecka-Pulker, M.; Klomfar, S.; Teufel, A.; Wochele-Thoma, T. Employer impact on COVID-19 vaccine uptake among nursing and social care employees in Austria. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1023914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikonja, N.K.; Hussein, M.; Verdenik, I.; Velikonja, V.G.; Erjavec, K. COVID-19 vaccination intention at the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic in Slovenia. Slov. Med. J. 2022, 91, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Vavrickova, L.; Micopulos, C.; Suchanek, J.; Pilbauerova, N.; Perina, V.; Kapitan, M. COVID-19 among Czech Dentistry Students: Higher Vaccination and Lower Prevalence Compared to General Population Counterparts. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F.; Ranzieri, S. Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines 2021, 9, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papini, F.; Mazzilli, S.; Paganini, D.; Rago, L.; Arzilli, G.; Pan, A.; Goglio, A.; Tuvo, B.; Privitera, G.; Casini, B. Healthcare Workers Attitudes, Practices and Sources of Information for COVID-19 Vaccination: An Italian National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirotto, L.; Crescitelli, M.E.D.; De Panfilis, L.; Caselli, L.; Serafini, A.; De Fiore, L.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Costantini, M. Italian health professionals on the mandatory COVID-19 vaccine: An online cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1015090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelekar, A.K.; Lucia, V.C.; Afonso, N.M.; Mascarenhas, A.K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among dental and medical students. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2021, 152, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J. Public Health 2020, 43, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, A.K.; Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. Dental students’ attitudes and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, K.; Sobers, N.; Kumar, A.; Ojeh, N.; Scott, A.; Cave, C.; Gupta, S.; Bradford-King, J.; Sa, B.; Adams, O.P.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine intent among health care professionals of queen elizabeth hospital, barbados. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3309–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, S.; Nassar, D.K.; Nassar, M.K.; Saad, A.M.; Hamdy, F. Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers: A cross sectional study from Egypt. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbadawi, M.H.; Altayib, L.S.; Birier, A.B.; Ali, L.E.; Hasabo, E.A.; Esmaeel, M.A.; Elmahi, O.K. Beliefs and barriers of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among Sudanese healthcare workers in Sudan: A cross sectional study. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2132082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craxì, L.; Casuccio, A.; Amodio, E.; Restivo, V. Who Should Get COVID-19 Vaccine First? A Survey to Evaluate Hospital Workers’ Opinion. Vaccines 2021, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regazzi, L.; Marziali, E.; Lontano, A.; Villani, L.; Paladini, A.; Calabrò, G.E.; Laurenti, P.; Ricciardi, W.; Cadeddu, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward COVID-19 vaccination in a sample of Italian healthcare workers. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2116206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruch, M.; Toscani, P.; Grassi, N.; Zamagni, G.; Monasta, L.; Radaelli, D.; Livieri, T.; Manfredi, A.; D’errico, S. Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, K.; Dadouli, K.; Avakian, I.; Bogogiannidou, Z.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Gogosis, K.; Speletas, M.; Koureas, M.; Lagoudaki, E.; Kokkini, S.; et al. Factors Associated with Healthcare Workers’ (HCWs) Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccinations and Indications of a Role Model towards Population Vaccinations from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Greece, May 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Rahiotis, C.; Tseroni, M.; Madianos, P.; Tzoutzas, I. Attitudes toward Vaccinations and Vaccination Coverage Rates among Dental Students in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Tseroni, M.; Drositis, I.; Gamaletsou, M.N.; Koukou, D.M.; Bolikas, E.; Peskelidou, E.; Daflos, C.; Panagiotaki, E.; Ledda, C.; et al. Vaccination coverage rates and attitudes towards mandatory vaccinations among healthcare personnel in tertiary-care hospitals in Greece. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarre, C.; Roy, P.; Ledochowski, S.; Fabre, M.; Esparcieux, A.; Issartel, B.; Dutertre, M.; Blanc-Gruyelle, A.-L.; Suy, F.; Adelaide, L.; et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in French hospitals. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałucka, S.; Kusideł, E.; Głowacka, A.; Oczoś, P.; Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. Pre-Vaccination Stress, Post-Vaccination Adverse Reactions, and Attitudes towards Vaccination after Receiving the COVID-19 Vaccine among Health Care Workers. Vaccines 2022, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabert, B.K.; Gilkey, M.B.; Huang, Q.; Kong, W.Y.; Thompson, P.; Brewer, N.T. Primary care professionals’ support for COVID-19 vaccination mandates: Findings from a US national survey. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayan, D.; Nguyen, K.; Keisler, B. National attitudes of medical students towards mandating the COVID-19 vaccine and its association with knowledge of the vaccine. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, S.M.; Burrowes, S.A.B.; Hall, T.; Dobbins, S.; Ma, M.; Bano, R.; Yarrington, C.; Schechter-Perkins, E.M.; Garofalo, C.; Drainoni, M.-L.; et al. Healthcare workers’ attitudes on mandates, incentives, and strategies to improve COVID-19 vaccine uptake: A mixed methods study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2144048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J.; Bagot, K.L.; Hoq, M.; Leask, J.; Seale, H.; Biezen, R.; Sanci, L.; Manski-Nankervis, J.-A.; Bell, J.S.; Munro, J.; et al. Factors Influencing Australian Healthcare Workers’ COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions across Settings: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, A.; Dickinson, H.; Dimov, S.; Shields, M.; McAllister, A. The COVID-19 vaccine intentions of Australian disability support workers. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbat, B.; Sharavyn, B.; Tsai, F.-J. Attitudes towards Mandatory Occupational Vaccination and Intention to Get COVID-19 Vaccine during the First Pandemic Wave among Mongolian Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumari, R.; Singh, S.; Kandpal, S.D.; Kaushik, A. The dilemma of COVID-19 vaccination among Health Care Workers (HCWs) of Uttar Pradesh. Indian J. Community Health 2021, 33, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; Saurabh, S.; Kumar, P.; Verma, M.K.; Goel, A.D.; Gupta, M.K.; Bhardwaj, P.; Raghav, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students in India. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Fatima, L.; Ahmed, A.M.; Ali, S.A.; Memon, R.S.; Afzal, M.; Saeed, U.; Gul, S.; Ahmad, J.; Malik, F.; et al. Perception, Willingness, Barriers, and Hesistancy Towards COVID-19 Vaccine in Pakistan: Comparison between Healthcare Workers and General Population. Cureus 2021, 13, 19106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.; Qiu, H.; Chien, W.T.; Wong, J.C.; Chalise, H.N.; Hoang, H.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Chan, P.K.; Wong, M.C.; Cheung, A.W.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Willingness and Related Fac-tors Among Health Care Workers in 3 Southeast Asian Jurisdictions. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2228061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konje, E.T.; Basinda, N.; Kapesa, A.; Mugassa, S.; Nyawale, H.A.; Mirambo, M.M.; Moremi, N.; Morona, D.; Mshana, S.E. The Coverage and Acceptance Spectrum of COVID-19 Vaccines among Healthcare Professionals in Western Tanzania: What Can We Learn from This Pandemic? Vaccines 2022, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.T.; Hu, S.S.; Zhou, T.; Bonner, K.E.; Kriss, J.L.; Wilhelm, E.; Carter, R.J.; Holmes, C.; de Perio, M.A.; Lu, P.-J.; et al. Employer requirements and COVID-19 vaccination and attitudes among healthcare personnel in the U.S.: Findings from National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module, August–September 2021. Vaccine 2022, 40, 7476–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustapha, M.; Lawal, B.K.; Sha’aban, A.; Jatau, A.I.; Wada, A.S.; Bala, A.A.; Mustapha, S.; Haruna, A.; Musa, A.; Ahmad, M.H.; et al. Factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among University health sciences students in Northwest Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poyiadji, N.; Tassopoulos, A.; Myers, D.T.; Wolf, L.; Griffith, B. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates: Impact on Radiology Depart-ment Operations and Mitigation Strategies. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2022, 19, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloweidi, A.; Bsisu, I.; Suleiman, A.; Abu-Halaweh, S.; Almustafa, M.; Aqel, M.; Amro, A.; Radwan, N.; Assaf, D.; Abdullah, M.Z.; et al. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 Vaccines: An Analytical Cross–Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.I.; Aldukhail, A.M.; Albaqami, M.D.; Silvano, R.C.; Titi, M.A.; Arif, B.I.; Amer, Y.S.; Wahabi, H. Predictors of healthcare workers’ intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: A cross sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 29, 2314–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shen, P.; Xu, B.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Dai, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.-H. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among healthcare workers in obstetrics and gynecology during the first three months of vaccination campaign: A cross-sectional study in Jiangsu province, China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4946–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirolo, A.; Posfay-Barbe, K.M.; Rohner, D.; Wagner, N.; Blanchard-Rohner, G. Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccine Among Hospital Employees in the Department of Paediatrics, Gynaecology and Obstetrics in the University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Graziano, G.; Bonaccorso, N.; Conforto, A.; Cimino, L.; Sciortino, M.; Scarpitta, F.; Giuffrè, C.; Mannino, S.; Bilardo, M.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Vaccination Acceptance/Hesitancy among the Community Pharmacists of Palermo’s Province, Italy: From Influenza to COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, F.B.; Nasim, A.; Saleem, S.; Jafarey, A.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health service providers: A single cen-tre experience from Karachi, Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Sarzyńska, K.; Czwojdziński, E.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Dudek, K.; Piwowar, A. Attitude of Health Care Workers and Medical Students towards Vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, R.; Lantieri, F.; Barranco, R.; Tettamanti, C.; Bonsignore, A.; Ventura, F. A Survey on Undergraduate Medical Stu-dents’ Perception of COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Pavli, A.; Dedoukou, X.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Raftopoulos, V.; Drositis, I.; Bolikas, E.; Ledda, C.; Adamis, G.; Spyrou, A.; et al. Determinants of intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 among healthcare personnel in hospitals in Greece. Infect. Dis. Health 2021, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulbrichtova, R.; Svihrova, V.; Tatarkova, M.; Hudeckova, H.; Svihra, J. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare and Non-Healthcare Workers of Hospitals and Outpatient Clinics in the Northern Region of Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qunaibi, E.; Basheti, I.; Soudy, M.; Sultan, I. Hesitancy of Arab Healthcare Workers towards COVID-19 Vaccination: A Large-Scale Multinational Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badahdah, A.M.; Al Mahyijari, N.; Badahdah, R.; Al Lawati, F.; Khamis, F. Attitudes of Physicians and Nurses in Oman To-ward Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination. Oman Med. J. 2022, 37, e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, D.; Blackshaw, B.P. COVID-19 Vaccination Should not be Mandatory for Health and Social Care Workers. New Bioeth. 2022, 28, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomhwange, T.; Wariri, O.; Nkereuwem, E.; Olanrewaju, S.; Nwosu, N.; Adamu, U.; Danjuma, E.; Onuaguluchi, N.; Enegela, J.; Nomhwange, E.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst healthcare workers: An assessment of its magnitude and determinants during the initial phase of national vac-cine deployment in Nigeria. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 50, 101499. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(22)00229-2/fulltext (accessed on 1 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-D.; Ding, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, J.-J.; Azkur, A.K.; Azkur, D.; Gan, H.; Sun, Y.-L.; Fu, W.; Li, W.; et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: A review. Allergy 2021, 76, 428–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolu, I.; Turhan, Z.; Dilcen, H.Y. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance is associated with Vaccine Hesitancy, Perceived Risk and Previous Vaccination Experiences. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 17, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, R.I. Mandatory vaccination of health care workers: Whose rights should come first? Pharm. Ther. 2009, 34, 615–618. [Google Scholar]

- Sprengholz, P.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, L.D.; Dyzel, V.; Sterkenburg, P.S. COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions amongst Healthcare Workers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, K.; Sen, A.; Goel, P.; Satapathy, P.; Jain, L.; Vij, J.; Patro, B.K.; Kar, S.S.; Chakrapani, V.; Singh, R.; et al. Community health workers willingness to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trials and intention to vaccinate: A cross-sectional survey in India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 17, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Corradi, A.; Voglino, G.; Catozzi, D.; Olivero, E.; Corezzi, M.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Healthcare Workers’ (HCWs) attitudes to-wards mandatory influenza vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 901–914. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X20316558 (accessed on 2 January 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberis, I.; Myles, P.; Ault, S.K.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Martini, M. History and evolution of influenza control through vaccination: From the first monovalent vaccine to universal vaccines. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2016, 57, E115–E120. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, L.G.; Lüthy, A.; Ramanathan, P.L.; Baldesberger, N.; Buhl, A.; Thurneysen, L.S.; Hug, L.C.; Suggs, L.S.; Speranza, C.; Huber, B.M.; et al. Healthcare profes-sional and professional stakeholders’ perspectives on vaccine mandates in Switzerland: A mixed-methods study. Vaccine 2022, 51, 7397–7405. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35164988/ (accessed on 1 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Seale, H.; Leask, J.; Macintyre, C.R. Do they accept compulsory vaccination? Awareness, attitudes and behaviour of hospital health care workers following a new vaccination directive. Vaccine 2009, 27, 3022–3025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19428914/ (accessed on 7 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Pitts, S.I.; Maruthur, N.M.; Millar, K.; Perl, T.M.; Segal, J. A Systematic Review of Mandatory Influenza Vaccination in Healthcare Personnel. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randi, B.A.; Sejas, O.N.E.; Miyaji, K.T.; Infante, V.; Lara, A.N.; Ibrahim, K.Y.; Lopes, M.H.; Sartori, A.M.C. A systematic review of adult tetanus-diphtheria-acellular (Tdap) coverage among healthcare workers. Vaccine 2019, 37, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buse, K.; Mays, N.; Walt, G. Making Health Policy, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data. Political Participation. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/political-participation-eiu?country=ARG~AUS~BWA~CHN (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI). Political Transformation. BTI 2022. Available online: https://bti-project.org/en/index/political-transformation (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Mouter, N.; Hernandez, J.I.; Itten, A.V. Public participation in crisis policymaking. How 30,000 Dutch citizens advised their government on relaxing COVID-19 lockdown measures. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartaxo, A.N.S.; Barbosa, F.I.C.; Bermejo, P.H.D.S.; Moreira, M.F.; Prata, D.N. The exposure risk to COVID-19 in most affected countries: A vulnerability assessment model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, S.; Malla, K.P.; Adhikari, R. Current scenario of COVID-19 pandemics in the top ten worst-affected countries based on total cases, recovery, and death cases. Appl. Sci. Technol. Ann. 2020, 1, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Khan, A.; Khan, J.; Khatoon, N.; Arshad, S.; Escalante, P.D.L.R. Death caused by COVID-19 in top ten countries in Asia affected by COVID-19 pandemic with special reference to Pakistan. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e248281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. Global Parliamentary Report 2022—Public Engagement in the Work of Parliament. Available online: https://www.ipu.org/impact/democracy-and-strong-parliaments/global-parliamentary-report/global-parliamentary-report-2022-public-engagement-in-work-parliament (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). Enhancing Public Trust in COVID-19 Vaccination: The Role of Governments. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/enhancing-public-trust-in-COVID-19-vaccination-the-role-of-governments-eae0ec5a/ (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Morens, D.M.; Folkers, G.K.; Fauci, A.S. The Concept of Classical Herd Immunity May Not Apply to COVID-19. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schryver, A.; Lambaerts, T.; Lammertyn, N.; François, G.; Bulterys, S.; Godderis, L. European survey of hepatitis B vaccina-tion policies for healthcare workers: An updated overview. Vaccine 2020, 38, 2466–2472. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32057571/ (accessed on 23 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. The end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13782. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35342941/ (accessed on 23 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Chu, H.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z. The effect of publication bias magnitude and direction on the certainty in evidence. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 84–86. Available online: https://ebm.bmj.com/content/23/3/84?fbclid=IwAR1J_pEWygbT7E8YfRw-Ae9X1Mxs8FPMiuONCl-eHgqfsuIZSJWkzHmsfHU (accessed on 20 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Langan, D. Assessing heterogeneity in random-effects meta-analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2345, 67–89. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34550584/ (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlinarić, A.; Horvat, M.; Smolčić, V.Š. Dealing with the positive publication bias: Why you should really publish your negative results. Biochem. Med. 2017, 27, 030201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The importance of no evidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Petri, H.; Bienzeisler, N.; Beseler, A. Effects of politicization on the practice of science. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 188, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciurti, A.; Baccolini, V.; Renzi, E.; Migliara, G.; De Vito, C.; Marzuillo, C.; Villari, P. Attitudes of university students towards mandatory COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional survey: Antonio Sciurti. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32 (Suppl. S3), ckac131-344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenik, D.; Węgrzyn, M. Public Policy Timing in a Sustainable Approach to Shaping Public Policy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelli, S.; Chaimani, A. Challenges in meta-analyses with observational studies. Évid. Based Ment. Health 2020, 23, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Participants | Gender (Female) | Age (Years) | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | Saudi Arabia | n = 334 | - | - | HCWs |

| [49] | Sudan | n = 930 | 626 (67.3%) | Mean age: 28.7 ± 6.7 (SD) | Anesthesiologist: 2 (0.2%) Dentist: 92 (9.9%) Doctor: 585 (62.9%) Medical laboratory: 70 (7.5%) Nurse: 27 (2.9%) Pharmacist: 118 (12.7%) Physiotherapist: 4 (0.4%) Radiologist: 6 (0.6%) Staff in medical university: 26 (2.8%) |

| [43] | Italy | n = 4677 | Female: 3132 (67.0%) Male: 1475 (31.5%) Not specified: 65 (1.4%) Other: 5 (0.1%) | 18–30: 389 (8.3) 31–40: 866 (18.5) 41–50: 1169 (25.0) 51–60: 1380 (29.5) >60: 873 (18.7) | Health professionals: 2474 (52.9%) Nursing health professionals: 1230 (26.3%) Obstetric health professionals: 79 (1.7%) Rehabilitation health professionals: 482 (10.3%) Technical health professionals: 179 (3.8%) Prevention health professionals: 29 (0.6%) Health operators: 204 (4.4%) |

| [32] | Cyprus | n = 504 | 320 (63%) | Mean age: 36.7 ± 9.6 (SD) | Physicians: 62 (13.3%) Nursing staff: 223 (48%) Pharmacists: 76 (16.3%) Non-medical professionals: 62 (13.3%) Physiotherapists: 31 (6.7%) |

| [35] | Turkey | n = 506 | 297 (58%) | 26–35: 169 (33%) 36–44: 168 (33) 45–60: 153 (30%) >60: 16 (4%) | Pediatricians: 506 (100%) |

| [36] | France | n = 4349 | 2806 (77.4%) | <25: 202 (5.6%) 25–40: 1675 (46.2%) 41–50: 908 (25.1%) >50: 838 (23.1%) Missing: 29 (16.7%) | Frontline caregivers: 1940 (53.6%) Other caregivers: 1018 (28.1%) Administrative and non-caregiver staff: 624 (17.3%) Unclassified: 35 (1.0%) Missing: 730 (16.8%) |

| [44] | USA | n = 415 | - | - | Medical students: 163 (39%) Dental students: 245 (59%) |

| [47] | Barbados | n = 343 | 260 (76%) | 18–34: 144 (42%) >35: 199 (58%) | Medical Doctors: 119 (34.7%) Nurses: 144 (42%) Allied health/Admin: 80 (23.3%) |

| [45] | USA | n = 168 | 96 (57%) | - | Medical students: 168 (100%) |

| [46] | USA | n = 248 | - | Mean age: 26.3 ± 3.8 (SD) | Dental students: (100%) |

| [29] | Saudi Arabia | n = 674 | 324 (48.1%) | 18–29: 392 (58.2%) 30–49: 251 (37.2%) 50–64: 27 (4%) >64: 4 (0.6%) | Medical doctors: 76 (11.3%) Dentists: 191 (28.3%) Nurses: 41 (6.1%) Pharmacists: 29 (4.3%) Dental assistants/Hygienists: 6 (0.9%) Dental technicians: 6 (0.9%) Healthcare students: 238 (35.3%) Other health professionals: 87 (12.9%) |

| [33] | Turkey | n = 1808 | 1227 (68.1%) | 18–35: 780 (43.3%) 36–50: 664 (36.9%) >50: 357 (19.8%) | Physicians: 927 (51.5%), Nurses and midwives: 479 (24.6%) Medical technicians: 80 (4.4%) Aides or helpers: 93 (5.2%) Other: 222 (12.3%) |

| [42] | Italy | n = 2137 | 1528 (71.70%) | <31: 190 (8.92%) 31–40: 440 (20.65%) 41–50: 571 (26.79%) 51–60: 700 (32.85%) >60: 230 (10.79%) | Medical Doctors: 634 (29.91%) Nurses: 894 (42.17%) Auxiliary nurses: 100 (4.72%) Technicians: 189 (8.92%) Pharmacists: 24 (1.13%) Territorial medicine: 74 (3.50%) Administration: 111 (5.26%) Other: 64 (3.03%) |

| [28] | Saudi Arabia | n = 673 | 268 (39.82%) | 18–29: 147 (21.84%) 30–39: 305 (45.32%) 40–49: 141 (20.95%) 50–59: 56 (8.32%) ≥60: 24 (3.57%) | Frontline healthcare worker: • Yes: 327 (48.59%) • No: 346 (51.41%) |

| [41] | Italy | n = 166 | 99 (59.6%) | Mean age: 49.1 ± 10.7 (SD) <50: 106 (63.9%) >50: 60 (36.1%) | Occupational Physicians: 166 (100%) |

| [38] | Austria | n = 612 | Female: 444 (73.15%) Male: 160 (26.36%) Diverse: 3 (0.49%) | Mean age: 42.7 ± 10.56 (SD) | Nursing and social care employees: 100% |

| [40] | Czech Republic | n = 240 | 73.75% | 20–23 years: 58.3% 24–29 years: 41.7% | Dental students: 240 (100%) |

| [30] | Saudi Arabia | n = 1285 | 822 (64%) | 25–34: 434 (33.8%) 35–44: 477 (37.1%) 45–54: 273 (21.2%) ≥55: 101 (7.9%) | Physician: 162 (68.1%) Other: 76 (31.9%) |

| [48] | Egypt | n = 455 | 367 (80.7%) | 18–24: 51 (11.2%) 25–35: 182 (40%) 36–45: 132 (29%) 46–60: 86 (18.9%) >60: 4 (0.9%) | Physicians: 118 (25.9%) Nurses: 172 (37.8%) Dentists: 6 (1.3%) Pharmacists: 10 (2.2%) Administrators: 46 (10.1%) Radiology or laboratory technicians: 20 (4.4%) Workers or security officers: 24 (5.3%) Other: 59 (13%) |

| [39] | Slovenia | n = 832 | - | - | HCWs |

| [37] | United Kingdom | n = 3235 | 2705 (74.3%) | 16–40: 1020 (31.5%) 40–55: 1239 (38.3%) >55: 963 (29.8%) | Medical staff: 778 (24.1%) Nursing staff: 698 (21.6%) Allied health professionals: 917 (28.4%) Pharmacy staff: 62 (1.9%) Healthcare scientists: 146 (4.5%) Ambulance staff: 94 (2.9%) Dental staff: 93 (2.9%) Optical staff: 82 (2.5%) Admin/estates/other staff: 184 (5.7%) Missing: 103 (3.2%) |

| [34] | Turkey | n = 320 | 232 | Mean age: 37.0 ± 10.0 (SD) | HCWs |

| Study | Country | Participants | Gender (Female) | Age (Years) | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | USA | n = 209 | Female: 170 (81%) Male: 37 (18%) Transgender/non-binary: 2 (1%) | 18–35: 85 (41%) 36–45: 58 (28%) 46–55: 44 (21%) ≥56: 23 (10%) | Advanced practice providers (NP, CNM, PA): 14 (7%) Emergency medical technicians/paramedics: 18 (9%) Medical or patient care assistants: 14 (7%) Nurses (RN, LPN): 38 (18%) Physicians: 71 (34%) Social workers/mental health specialists: 14 (7%) Other: 40 (19%) |

| [50] | Italy | n = 465 | 225 (48%) | Mean age: 51 ± 9 (SD) | Physicians: 212 (45.6%) Nurses: 120 (25.8%) Healthcare technicians: 41 (8.8%) Administrative/other: 92 (19.8) |

| [49] | Sudan | n = 930 | 626 (67.3%) | Mean age: 28.7 ± 6.7 (SD) | Anesthesiologists: 2 (0.2%) Dentists: 92 (9.9%) Doctors: 585 (62.9%) Medical laboratory staff: 70 (7.5%) Nurses: 27 (2.9%) Pharmacists: 118 (12.7%) Physiotherapists: 4 (0.4%) Radiologists: 6 (0.6%) Staff in medical universities: 26 (2.8%) |

| [53] | Greece | n = 1132 | 804 | Mean age: 43.1 | Physicians: 428 (38%) Nurses: 515 (45%) Other: 189 (17%) |

| [43] | Italy | n = 4677 | Female: 3132 (67.0%) Male: 1475 (31.5%) Not specified: 65 (1.4%) Other: 5 (0.1%) | 18–30: 389 (8.3%) 31–40: 866 (18.5%) 41–50: 1169 (25%) 51–60: 1380 (29.5%) >60: 873 (18.7%) | Health professionals: 2474 (52.9%) Nursing health professionals: 1230 (26.3%) Obstetric health professionals: 79 (1.7%) Rehabilitation health professionals: 482 (10.3%) Technical health professionals: 179 (3.8%) Prevention health professionals: 29 (0.6%) Health operators: 204 (4.4%) |

| [32] | Cyprus | n = 504 | 320 (63%) | Mean age: 36.7 ± 9.6 (SD) | Physicians: 62 (13.3%) Nursing staff: 223 (48%) Pharmacists: 76 (16.3%) Non-medical professionals: 62 (13.3%) Physiotherapists: 31 (6.7%) |

| [58] | USA | n = 1047 | 515 (49%) | - | Physicians: 747 (71%) Other: 300 (29%) |

| [66] | India | n = 1068 | 519 (48%) | - | Medical students: 1068 (100%) |

| [36] | France | n = 4349 | 2806 (77.4%) | <25: 202 (5.6%) 25–40: 1675 (46.2%) 41–50: 908 (25.1%) >50: 838 (23.1%) Missing: 29 (16.7%) | Frontline caregivers: 1940 (53.6%) Other caregivers: 1018 (28.1%) Administrative and non-caregiver staff: 624 (17.3%) Unclassified: 35 (1.0%) Missing: 730 (16.8%) |

| [57] | Poland | n = 1051 | 830 (77%) | Mean age: 26.8 ± 9.7 (SD) 19–26: 815 (75.5%) >27: 260 (24.1%) Missing: 5 (0.5%) | Medical doctors: 135 (12.5%) Nurses and midwives: 128 (11.8%) Medical students: 423 (39.2%) Students of nursing and midwifery: 394 (36.5%) |

| [67] | Pakistan | n = 208 | 118 (57%) | Mean age: 27.78 ± 11.19 | HCWs |

| [62] | Australia | n = 3074 | 2532 (82%) | 18–49: 1643 (55.4%) >50: 1321 (44.6%) | Medical Doctors: 171 (5.6%) Nurses: 2071 (67.4%) Pharmacists: 53 (1.7%) Allied health professionals: 232 (7.5%) Personal support staff: 66 (2.1%) Ambulance staff: 124 (4.0%) Other: 357 (11.6%) |

| [63] | Australia | n = 252 | 178 (70%) | 18–29: 26 (11.7%) 30–49: 73 (32.9%) 50–64: 109 (49.1%) >65: 14 (6.3%) | Disability support workers: 252 (100%) |

| [44] | USA | n = 415 | - | - | Medical students: 163 (39%) Dental students: 245 (59%) |

| [69] | Tanzania | n = 811 | 388 (48%) | Mean age: 35 ± 9.04 | Cadre Medical attendants: 105 (12.9%) Nurses/clinical officers: 419 (51.7%) Doctors/specialists: 287 (35.4%) |

| [45] | USA | n = 168 | 96 (57%) | - | Medical students: 168 (100%) |

| [54] | Greece | n = 134 | 92 (68%) | - | Dental students: 134 (100%) |

| [55] | Greece | n = 1284 | 816 (63%) | ≤30: 214 (16.7%) 31–40: 317 (24.7%) 41–50: 384 (29.9%) >50: 367 (28.6%) | Physicians: 402 (31.3%) Nursing personnel: 470 (36.6%) Paramedical personnel: 142 (11.1%) Administrative personnel: 170 (13.2%) Supportive personnel: 94 (7.3%) Unknown: 6 (0.5%) |

| [46] | USA | n = 248 | - | Mean age: 26.3 ± 3.8 (SD) | Dental students: (100%) |

| [59] | USA | n = 1899 | 1221 (64.3%) | <25: 649 (34.18%) 25–29: 1091 (57.45%) >30: 159 (8.37%) | Medical students: 1899 (100%) |

| [56] | France | n = 1964 | 1532 (78%) | 18–29: 306 (16%) 30–49: 1.118 (57%) >50: 540 (27%) | Physicians: 423 (21.5%) Paramedical staff: 876 (44.6%) Administrative workers: 432 (22.0%) Technical staff: 213 (10.8%) Other: 20 (1.0%) |

| [52] | Italy | n = 130 | 97 (74.6%) | ≤30: 24 (18.5%) 31–40: 29 (22.3%) 41–50: 34 (26.2%) 51–60: 39 (30.0%) >60: 4 (3.1%) | Physicians: 38 (29%) Nurses: 58 (44%) Other HCWs: 34 (27%) |

| [51] | Italy | n = 2142 | Female: 1125 (52.5%) Male: 1007 (47.0%) Not specified: 10 (0.5%) | 15–25: 40 (1.9%) 26–35: 327 (15.3%) 36–45: 299 (14.0%) 46–55: 399 (18.6%) 56–65: 601 (28.0%) 66–75: 436 (20.3%) 76–85: 36 (1.7%) 86–95: 4 (0.2%) | Physicians: 1538 (71.8%) Dentists: 171 (8.0%) Nurses: 275 (12.8%) Chemists: 3 (0.1%) Healthcare assistants: 19 (0.9%) Other: 136 (6.4%) |

| [40] | Czech Republic | n = 240 | 73.75% | 20–23: 58.3% 24–29: 41.7% | Dental students: 240 (100%) |

| [60] | USA | n = 3479 | Female: 2598 (75%) Male: 864 (25%) Trans/Gender non-binary/not specified above: 7 (0.2%) Do not wish to reply: 10 (0.3%) | 18–30: 816 (23%) 31–40: 1061 (30%) 41–50: 686 (20%) 51–60: 571 (16%) 61–70: 326 (9.4%) >70: 19 (0.5%) | Direct Patient Care Providers (DPCPs): 1573 (45%) Direct medical providers (DMPs): 1207 (35%) Administrative staff working in hospitals without direct patient contact: 295 (8.5%) Others without direct patient contact: 404 (12%) |

| [65] | India | n = 254 | 72 (28.3%) | - | Medical doctors: 172 (67.7%) Paramedical workers: 82 (32.3%) |

| [48] | Egypt | n = 455 | 367 (80.7%) | 18–24: 51 (11.2%) 25–35: 182 (40%) 36–45: 132 (29%) 46–60: 86 (18.9%) more than 60: 4 (0.9%) | Physicians: 118 (25.9%) Nurses: 172 (37.8%) Dentists: 6 (1.3%) Pharmacists: 10 (2.2%) Administrators: 46 (10.1%) Radiology or laboratory technicians: 20 (4.4%) Workers or security officers: 24 (5.3%) Other: 59 (13%) |

| [64] | Mongolia | n = 238 | 195 (81.9%) | 18–25: 18 (7.6%) 26–35: 148 (62.2%) 36–45: 48 (20.2%) 46–55: 20 (8.4%) >55: 4 (1.7%) | Physicians: 162 (68.1%) Other: 76 (31.9%) |

| [68] | Hong Kong, Nepal, Vietnam | n = 3396 | 2589 (76.2%) | 18–29: 560 (16.5%) 30–39: 1058 (31.2%) 40–49: 834 (24.6%) ≥50: 928 (27.3%) | Nurses: 2636 (77.6%) Doctors: 760 (22.4%) |

| [37] | United Kingdom | n = 3235 | 2705 (74.3%) | 16–40: 1020 (31.5%) 40–55: 1239 (38.3%) >55: 963 (29.8%) | Medical staff: 778 (24.1%) Nursing staff: 698 (21.6%) Allied health professionals: 917 (28.4%) Pharmacy staff: 62 (1.9%) Healthcare scientists: 146 (4.5%) Ambulance staff: 94 (2.9%) Dental staff: 93 (2.9%) Optical staff: 82 (2.5%) Admin/estates/other staff: 184 (5.7%) Missing: 103 (3.2%) |

| HCWs for the General Population | HCWs for HCWs | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | 50% (95% CI: 38%, 61%) | 64% (95% CI: 55%, 72%) |

| Alternative dichotomization—sensitivity analysis | 56% (95% CI: 43%, 67%) | 68% (95% CI: 59%, 75%) |

| Risk of bias assessment—sensitivity analysis | 45% (95% CI: 30%, 60%) | 55% (95% CI: 41%, 69%) |

| Sub-Groups | Percentage (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| By W.H.O. regions for HCWs | |

| African and Eastern Mediterranean Region | 57% (33%, 78%) |

| Western Pacific and South-East Asia Region | 67% (57%, 75%) |

| European Region | 59% (40%, 76%) |

| Region of the Americas | 70% (54%, 82%) |

| By W.H.O. regions for the general population | |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 63% (47%, 76%) |

| Region of the Americas | 46% (32%, 60%) |

| European Region | 44% (28%, 62%) |

| By year of publication for HCWs | |

| 2021 | 56% (47%, 65%) |

| 2022 | 69% (54%, 80%) |

| By year of publication for the general population | |

| 2021 | 48% (34%, 63%) |

| 2022 | 51% (34%, 68%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Politis, M.; Sotiriou, S.; Doxani, C.; Stefanidis, I.; Zintzaras, E.; Rachiotis, G. Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2023, 11, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040880

Politis M, Sotiriou S, Doxani C, Stefanidis I, Zintzaras E, Rachiotis G. Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2023; 11(4):880. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040880

Chicago/Turabian StylePolitis, Marios, Sotiris Sotiriou, Chrysoula Doxani, Ioannis Stefanidis, Elias Zintzaras, and Georgios Rachiotis. 2023. "Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Vaccines 11, no. 4: 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040880

APA StylePolitis, M., Sotiriou, S., Doxani, C., Stefanidis, I., Zintzaras, E., & Rachiotis, G. (2023). Healthcare Workers’ Attitudes towards Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines, 11(4), 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040880

_Rachiotis.png)