Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Respondents and Sampling

2.3. Instrument Development and Measures

2.4. Scoring System

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Cancer-Related Characteristics

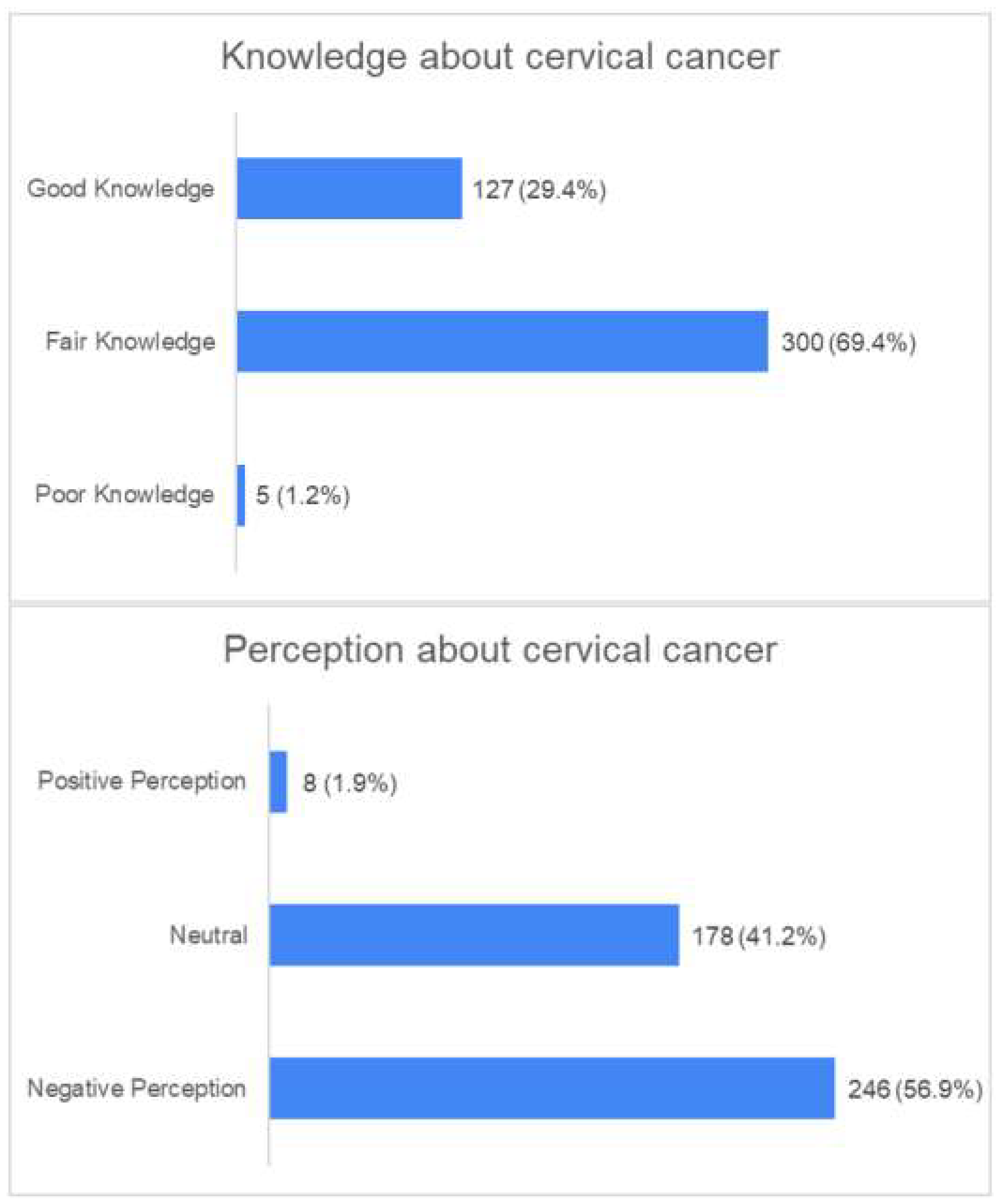

3.2. Participants’ Knowledge and the Associated Factors

3.3. Participants Perceptions and the Associated Factors

3.4. Facilitators and Barriers to HPV Vaccine Uptake

3.5. Correlation between Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Recommendation and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeferino, L.C.; Derchain, S.F. Cervical Cancer in the Developing World. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkour, K.; Alghuson, L.; Benabdelkamel, H.; Alhalal, H.; Alayed, N.; AlQarni, A.; Arafah, M. Cervical Cancer and Human Papillomavirus Awareness among Women in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2021, 57, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 370, 890–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report Saudi Arabia 2015; Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2018. Available online: https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/NCC/Activities/AnnualReports/2015%20E%20SCR%20final%206%20NOV.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.; De Sanjosé, S. Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in China; ICO/IARC HPV Information Centre, China. Summary Report. 2021. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/CHN.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Rijo, J.; Ross, H. The Global Economic Cost of Cancer; American Cancer Society: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hull1, R.; Mbele, M.; Makhafola, T.; Hicks, C.; Wang, S.M.; Reis, R.M.; Mehrotra, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.; Kibiki, G.; Bates, D.O.; et al. Cervical Cancer in Low and Middle.Income Countries (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeian, F.; Ghaemimood, S.; El-Khatib, Z.; Enayati, S.; Mirkazemi, R.; Reeder, B. Burden of Cervical Cancer in the Eastern Mediterranean Region During the Years 2000 and 2017: Retrospective Data Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, R. (Ed.) Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control. In Cervical Cancer—A Global Public Health Treatise; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al Madani, W.; Ahmed, A.E.; Arabi, H.; Al Khodairy, S.; Al Mutairi, N.; Jazieh, A.R. Modelling Risk Assessment for Cervical Cancer in Symptomatic Saudi Women. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatla, N.; Singhal, S. Primary HPV Screening for Cervical Cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 65, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldohaian, A.I.; Alshammari, S.A.; Arafah, D.M. Using the Health Belief Model to Assess Beliefs and Behaviors Regarding Cervical Cancer Screening among Saudi Women: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.M.; Qarah, A.B.; Alharbi, A.M.; Alomar, A.E.; Almubarak, S.A. Awareness and Practices Related to Cervical Cancer among Females in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endarti, D.; Kristina, S.A.; Farida, M.A.; Rahmawanti, Y.; Andriani, T. Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Women in Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, R.; Yadav, K. Cervical Cancer: Formulation and Implementation of Govt of India Guidelines for Screening and Management. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmeister, C.A.; Khan, S.F.; Schäfer, G.; Mbatani, N.; Adams, T.; Moodley, J.; Prince, S. Cervical Cancer Therapies: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 13, 200238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsbeih, G. HPV Infection in Cervical and Other Cancers in Saudi Arabia: Implication for Prevention and Vaccination. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, M.; Autier, P. Cancer Prevention: Cervical Cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jradi, H.; Bawazir, A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Saudi Women Regarding Cervical Cancer, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Corresponding Vaccine. Vaccine 2019, 37, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malibari, S. Knowledge about Cervical Cancer among Women in Saudi Arabia. Egypt J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 70, 1823–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnafisah, R.A.; Alsuhaibani, R.A.; Alharbi, M.A.; Alsohaibani, A.A.; Ismai, A.A. Saudi Women’s Knowledge and Attitude toward Cervical Cancer Screening, Treatment, and Prevention: A Cross-Sectional Study in Qassim Region (2018–2019). Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 2965–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajeh, M.; Alshammari, S. Awareness of human papillomavirus and its vaccine among patients attending primary care clinics at King Saud University Medical City. J. Nat. Sci. Med. 2020, 3, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.I.; Mohamed, R.A.; Alblawi, A.A. Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Cervical Cancer Screening and Human Papillomavirus (Hpv) Vaccine among Female Students in Jouf University. Int. Med. J. 2021, 28, 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Altamimi, T. Human Papillomavirus and Its Vaccination: Knowledge and Attitudes among Female University Students in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgzar, W.T.; Al-Thubaity, D.D.; Alshahrani, M.A.; Nahari, M.H.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Sayed, S.H.; El Sayed, H.A. Predictors of Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Attitude among Saudi Women in Najran City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2022, 26, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gerend, M.A.; Shepherd, J.E. Predicting Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in Young Adult Women: Comparing the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 44, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Wong, Y.L.; Low, W.Y.; Khoo, E.M.; Shuib, R. Knowledge and Awareness of Cervical Cancer and Screening among Malaysian Women Who Have Never Had a Pap Smear: A Qualitative Study. Singap. Med. J. 2009, 50, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, P.L.; Brewer, N.T.; Gottlieb, S.L.; McRee, A.L.; Smith, J.S. Parents’ Health Beliefs and HPV Vaccination of Their Adolescent Daughters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; El-Sayed, T.; Elsayed, R.; Aboushady, R. Effect of Tele-Nursing Instructions on Women Knowledge and Beliefs about Cervical Cancer Prevention. Assiut Sci. Nurs. J. 2021, 8, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18 to <30 y | 218 (51.8%) |

| 30 to <40 y | 105 (24.9%) | |

| 40 to <50 y | 98 (23.3%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 169 (40.1%) |

| Married | 231 (54.9%) | |

| Widow | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Divorced | 17 (4.0%) | |

| Education | School education | 101 (24%) |

| Bachelor degree | 273 (64.8%) | |

| Diploma degree | 39 (9.3%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 8 (1.9%) | |

| Employment status | Student | 158 (37.5%) |

| Employed | 86 (20.4%) | |

| Unemployed | 177 (42.1%) | |

| Region * | Northern Region | 163 (38.7%) |

| Southern Region | 135 (32.1%) | |

| Eastern Region | 19 (4.5%) | |

| Western Region | 50 (11.9%) | |

| Central Region | 54 (12.8%) | |

| Have a family history of cancer | 114 (27.2%) | |

| Cancer-related characteristics | Ever heard about cervical cancer | 332 (78.9%) |

| Ever heard about HPV vaccination | 131 (31.1%) | |

| Ever heard about screening | 276 (65.6%) | |

| Ever screened against CC | 35 (8.3%) | |

| Ever vaccinated against CC | 46 (10.9%) | |

| Having family who have been screened | 85 (20.2%) | |

| Having family who have been vaccinated | 53 (12.6%) |

| Parameter | Knowledge | Perception |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum, Maximum | 20.0, 46.0 | 12.0, 44.0 |

| Mean ± SD | 34.7 ± 3.7 | 33.1 ± 5.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 35.0 (33.0, 37.0) | 33.0 (30.0, 36.0) |

| Parameter | Category | Univariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | Intercept | p | ||

| Age | 18 to <30 y | - | - | |

| 30 to <40 y | 0 | 33 | 0.302 | |

| 40 to <50 y | 0 | 33 | 0.747 | |

| Marital status | Single | - | - | |

| Married | 0 | 33 | 0.48 | |

| Widow * | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Divorced * | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Education | School education | - | - | |

| Bachelor degree | 0 | 33 | 0.524 | |

| Diploma degree | 0 | 33 | 0.776 | |

| Postgraduate degree * | −3 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | Student | - | - | |

| Unemployed | 0 | 33 | 0.643 | |

| Employed | 0 | 33 | 0.771 | |

| Region | Northern Region | - | - | |

| Southern Region | 0 | 33 | 0.535 | |

| Eastern Region * | −1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Western Region * | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Central Region * | −1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Have a family history of cancer * | No | - | - | |

| Yes | −1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Ever heard about cervical cancer * | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Ever heard about HPV vaccination | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0 | 33 | 0.169 | |

| Ever heard about screening * | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 32 | <0.001 | |

| Ever screened against CC | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0 | 33 | 0.451 | |

| Ever vaccinated against CC * | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Having family who have been screened * | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 33 | <0.001 | |

| Having family who have been vaccinated | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0 | 33 | 0.238 | |

| Parameter | Category | Univariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | Intercept | p | ||

| Age | 18 to <30 y | - | - | |

| 30 to <40 y | −1 | 30 | <0.001 | |

| 40 to <50 y | 1 | 29 | 0.006 | |

| Marital status | Single | - | - | |

| Married | 1 | 29 | 0.002 | |

| Widow | −2 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Divorced | −1 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Education | School education | - | - | |

| Bachelor degree | −1 | 30 | 0.007 | |

| Diploma degree | 1 | 29 | 0.705 | |

| Postgraduate degree | −1 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | Student | - | - | |

| Unemployed | −1 | 30 | <0.001 | |

| Employed | 0 | 29 | 0.009 | |

| Region | Northern Region | - | - | |

| Southern Region | 1 | 29 | 0.012 | |

| Eastern Region | 0 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Western Region | 1 | 29 | 0.244 | |

| Central Region | −1 | 30 | <0.001 | |

| Have a family history of cancer | No | - | - | |

| Yes | −0.5 | 29.5 | 0.003 | |

| Ever heard about cervical cancer | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Ever heard about HPV vaccination | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Ever heard about screening | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 0.5 | 29 | <0.001 | |

| Ever screened against CC | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | 0.604 | |

| Ever vaccinated against CC | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | 0.121 | |

| Having family who have been screened | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | 0.028 | |

| Having family who have been vaccinated | No | - | - | |

| Yes | 1 | 29 | 0.281 | |

| Knowledge | Perception | Accepts to Take HPV Vaccine/Screening | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Spearman Correlation | 1 | 0.318 | 0.177 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Perception | Spearman Correlation | 0.318 | 1 | 0.476 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Accepts to take HPV vaccine/screening | Spearman Correlation | 0.177 | 0.476 | 1 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rezq, K.A.; Algamdi, M.; Alanazi, R.; Alanazi, S.; Alhujairy, F.; Albalawi, R.; Al-Zamaa, W. Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071188

Rezq KA, Algamdi M, Alanazi R, Alanazi S, Alhujairy F, Albalawi R, Al-Zamaa W. Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2023; 11(7):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071188

Chicago/Turabian StyleRezq, Khulud Ahmad, Maadiah Algamdi, Raghad Alanazi, Sarah Alanazi, Fatmah Alhujairy, Radwa Albalawi, and Wafa Al-Zamaa. 2023. "Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study" Vaccines 11, no. 7: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071188

APA StyleRezq, K. A., Algamdi, M., Alanazi, R., Alanazi, S., Alhujairy, F., Albalawi, R., & Al-Zamaa, W. (2023). Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and Screening for Cervical Cancer among Saudi Females: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines, 11(7), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071188