Recommended Interventions to Improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents: A Review of Quality Improvement Methodologies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Database Search

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Primary Outcome

2.4. Study Registration

3. Results

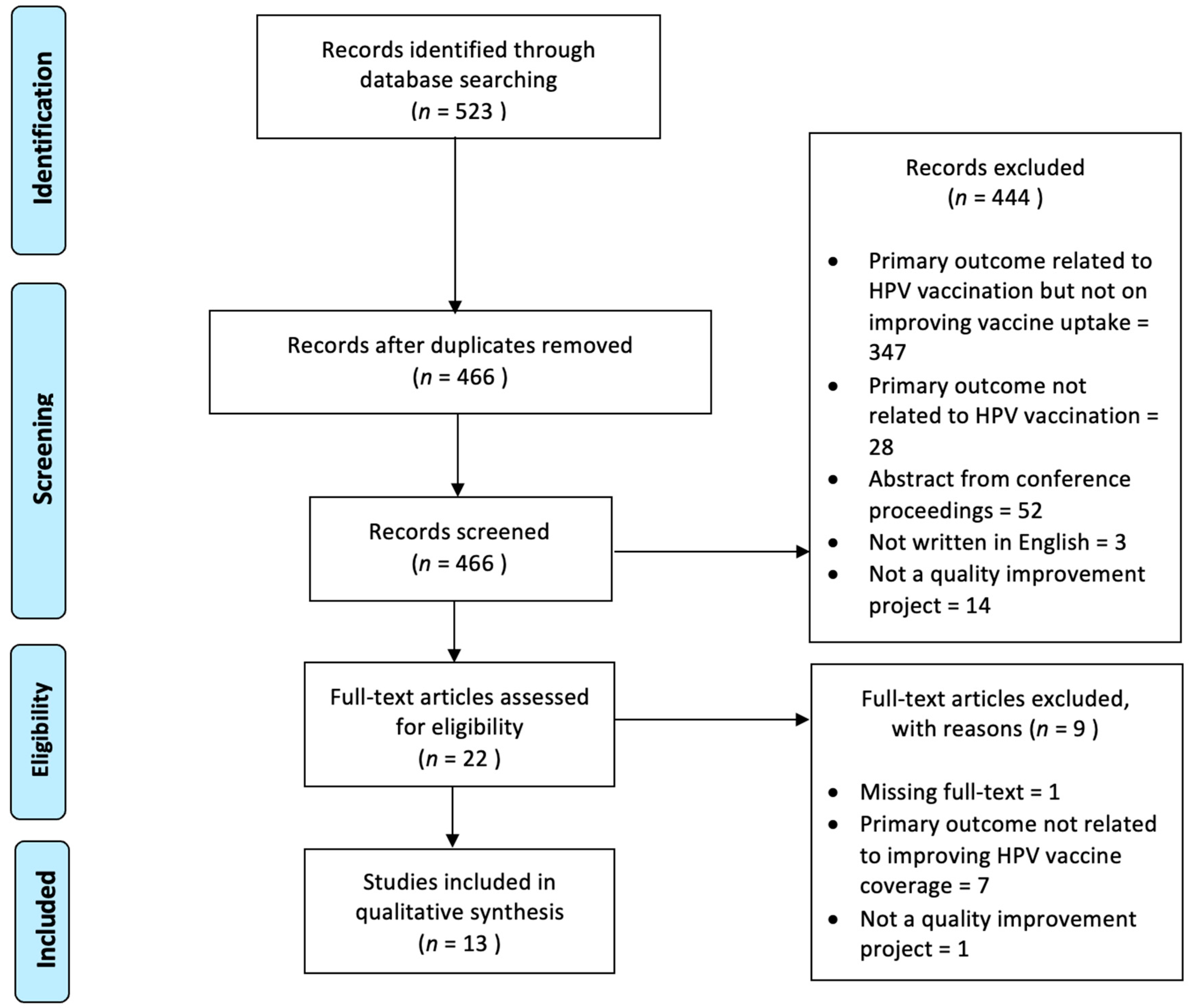

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Healthcare Provider-Targeted Empowerment Approach

3.3. Reshaping Adolescents’, Parents’, and/or Caregivers’ Perception of HPV Vaccination

3.4. Redesigning Healthcare Systems and Changing Policies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, K.R.; Norman, S.L.; Olson, B.G.; Demirel, S.; Taha, A.A. A Clinical Educational Intervention to Increase HPV Vaccination Rates Among Pediatric Patients Through Enhanced Recommendations. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2022, 36, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. HPV Vaccination Recommendations; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–2.

- Wallace-Brodeur, R.; Li, R.; Davis, W.; Humiston, S.; Albertin, C.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Rand, C.M. A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates in Local Health Department Clinics. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, C.; Yankey, D.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Markowitz, L.E.; Williams, C.L.; Fredua, B.; McNamara, L.A.; Stokley, S.; Singleton, J.A. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2021, 70, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, B.; Morgan, H. Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in the Family Practice Setting. J. Nurse Pract. 2019, 15, e123–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Saraiya, M.; Bhatt, A. Increasing HPV Vaccination Rates Through National Provider Partnerships. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. Action Plan—Towards the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in Malaysia 2021–2030, 1st ed.; Abdul Samad, S., Ed.; Ministry of Health, Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021.

- Kamzol, W.; Jaglarz, K.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Puskulluoglu, M.; Krzemieniecki, K. Assessment of Knowledge about Cervical Cancer and Its Prevention among Female Students Aged 17–26 Years. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 166, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michail, G.; Smaili, M.; Vozikis, A.; Jelastopulu, E.; Adonakis, G.; Poulas, K. Female Students Receiving Post-Secondary Education in Greece: The Results of a Collaborative Human Papillomavirus Knowledge Survey. Public Health 2014, 128, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimagambetova, G.; Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Issanov, A. What Factors Are Associated with Attitudes towards HPV Vaccination among Kazakhstani Women? Exploratory Analysis of Cross-Sectional Survey Data. Vaccines 2022, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkey, M.B.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Gerend, M.A.; Kornides, M.L.; Perkins, R.B.; Saslow, D.; Sienko, J.; Zimet, G.D.; Brewer, N.T. Getting Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Back on Track: Protecting Our National Investment in Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the COVID-19 Era. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 633–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiter, M.; Rositch, A.; Levinson, K.; Stone, R.; Fader, A.; Ferriss, J.; Wethington, S.; Beavis, A. The Gynecologic Oncologist as the HPV Champion: Missed Opportunities for Cancer Prevention. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, S292–S293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, T.A.; Broome, M.; Millman, J.; Epstein, J.; Derouin, A. Promoting Strategies to Increase HPV Vaccination in the Pediatric Primary Care Setting. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2022, 36, e36–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkey, M.B.; Parks, M.J.; Margolis, M.A.; McRee, A.-L.; Terk, J.V. Implementing Evidence-Based Strategies to Improve HPV Vaccine Delivery. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20182500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.K.; Thompson, K.; Abdulwahab, A.; Huntington, M.K. A Simple Intervention to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in a Family Medicine Practice. S. D. Med. 2019, 72, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mathur, M.; Campbell, S. Statewide Pediatric Quality Improvement Collaborative for HPV Vaccine Initiation. Wis. Med. J. 2019, 118, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- McGaffey, A.; Lombardo, N.P.; Lamberton, N.; Klatt, P.; Siegel, J.; Middleton, D.B.; Hughes, K.; Susick, M.; Lin, C.J.; Nowalk, M.P. A “Sense”-Ational HPV Vaccination Quality Improvement Project in a Family Medicine Residency Practice. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2019, 111, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, M.; Kerkvliet, J.L.; Polkinghorn, A.; Pugsley, L. Increasing Rates of Human Pipillomavirus Vaccination in Family Practice: A Quality Improvement Project. S. D. Med. 2019, 72, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliver, K.; McCorkell, C.; Pister, I.; Majid, N.; Benkel, D.H.; Zucker, J.R. Improving HPV Vaccine Delivery at School-Based Health Centers. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1870–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.B.; Foley, S.; Hassan, A.; Jansen, E.; Preiss, S.; Isher-Witt, J.; Fisher-Borne, M. Impact of a Multilevel Quality Improvement Intervention Using National Partnerships on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. Increasing Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus among Young Adults. J. Nurse Pract. 2022, 18, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smajlovic, A.; Toth, C.D. Quality Improvement Project to Increase Human Papillomavirus Two-Dose Vaccine Series Completion by 13 Years in Pediatric Primary Care Clinics. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, S.; Darville-Sanders, G.; Vu, T.; Carter, A.; Treend, K.; Raunio, C.; Vasavada, A. Multi-Level Quality Improvement Strategies to Optimize HPV Vaccination Starting at the 9-Year Well Child Visit: Success Stories from Two Private Pediatric Clinics. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2163807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskevaidis, E.; Athanasiou, A.; Paraskevaidi, M.; Bilirakis, E.; Galazios, G.; Kontomanolis, E.; Dinas, K.; Loufopoulos, A.; Nasioutziki, M.; Kalogiannidis, I.; et al. Cervical Pathology Following HPV Vaccination in Greece: A 10-Year HeCPA Observational Cohort Study. In Vivo 2020, 34, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasoulis, G.; Pouliakis, A.; Michail, G.; Kottaridi, C.; Spathis, A.; Kyrgiou, M.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Daponte, A. Alterations of HPV-Related Biomarkers after Prophylactic HPV Vaccination. A Prospective Pilot Observational Study in Greek Women. Cancers 2020, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, X. Understanding Health Empowerment from the Perspective of Information Processing: Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e27178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handayani, P.W.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Budi, I. User Acceptance Factors of Hospital Information Systems and Related Technologies: Systematic Review. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2018, 43, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askelson, N.M.; Ryan, G.; Seegmiller, L.; Pieper, F.; Kintigh, B.; Callaghan, D. Implementation Challenges and Opportunities Related to HPV Vaccination Quality Improvement in Primary Care Clinics in a Rural State. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.B.; Brogly, S.B.; Adams, W.G.; Freund, K.M. Correlates of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Rates in Low-Income, Minority Adolescents: A Multicenter Study. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, J. Disparities in HPV Vaccination Rates and HPV Prevalence in the United States: A Review of the Literature. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, H.W.; Meites, E.; Ekwueme, D.U.; Saraiya, M.; Markowitz, L.E. Updated Medical Care Cost Estimates for HPV-Associated Cancers: Implications for Cost-Effectiveness Analyses of HPV Vaccination in the United States. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahumud, R.A.; Alam, K.; Keramat, S.A.; Ormsby, G.M.; Dunn, J.; Gow, J. Cost-Effectiveness Evaluations of the 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine: Evidence from a Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, F.; Batalden, P.; Stevens, D.; Ogrinc, G.; Mooney, S. Publication Guidelines for Quality Improvement in Health Care: Evolution of the SQUIRE Project. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2008, 17 (Suppl. S1), i3–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | First Author, Year | Intervention Focus Group | Mode of Intervention | Primary Outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Berstein, 2022 [13] | System/policy |

|

|

|

| Patients |

| ||||

| HCP |

| ||||

| 2 | Davis, 2022 [1] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 3 | Gilkey, 2019 [14] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 4 | Mackey, 2019 [15] | HCP |

|

|

|

| Patients |

| ||||

| 5 | Mathur, 2019 [16] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 6 | McGaffey, 2019 [17] | HCP |

|

|

|

| Patients |

| ||||

| System/policy |

| ||||

| 7 | Nissen, 2019 [18] | Patients |

|

|

|

| HCP |

| ||||

| 8 | Oliver, 2020 [19] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 9 | Perkins, 2021 [20] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 10 | Singh, 2022 [21] | Patients |

|

|

|

| HCP |

| ||||

| 11 | Smajlovic, 2023 [22] | Patients |

|

|

|

| HCP |

| ||||

| System |

| ||||

| 12 | Wallace-Brodeur, 2020 [3] | HCP |

|

|

|

| 13 | Zorn, 2023 [23] | HCP |

|

|

|

| Setting/system |

| ||||

| Patients |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khalid, K.; Lee, K.Y.; Mukhtar, N.F.; Warijo, O. Recommended Interventions to Improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents: A Review of Quality Improvement Methodologies. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081390

Khalid K, Lee KY, Mukhtar NF, Warijo O. Recommended Interventions to Improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents: A Review of Quality Improvement Methodologies. Vaccines. 2023; 11(8):1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081390

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhalid, Karniza, Kun Yun Lee, Nur Farihan Mukhtar, and Othman Warijo. 2023. "Recommended Interventions to Improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents: A Review of Quality Improvement Methodologies" Vaccines 11, no. 8: 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081390

APA StyleKhalid, K., Lee, K. Y., Mukhtar, N. F., & Warijo, O. (2023). Recommended Interventions to Improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents: A Review of Quality Improvement Methodologies. Vaccines, 11(8), 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081390