COVID-19 Vaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy in the Gaza Strip from a Cross-Sectional Survey in 2023: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Associations with Health System Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

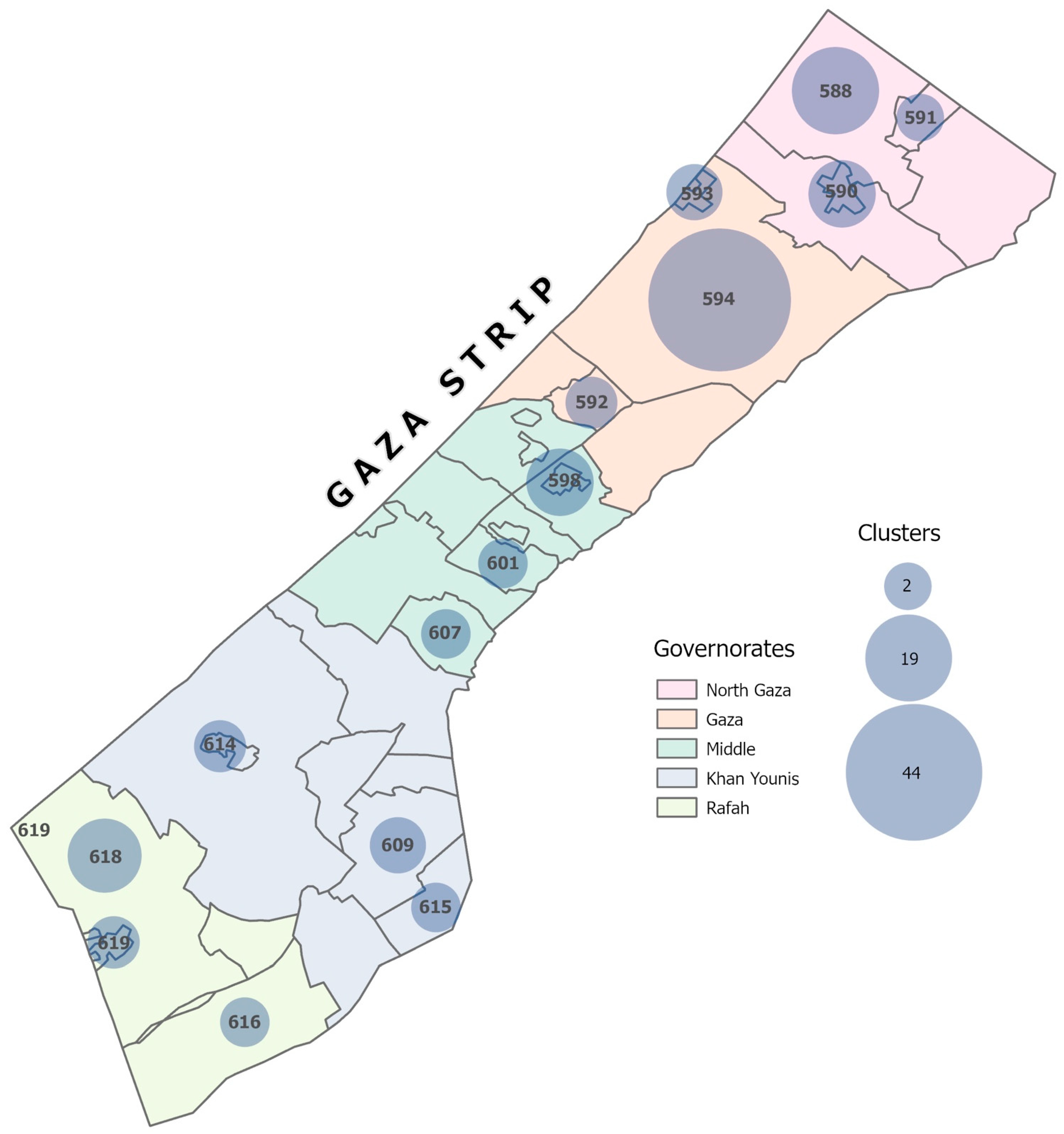

2.1. Sampling Design and Sample Size

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Survey Respondents

3.2. Vaccine Outcomes

3.2.1. Vaccination Status

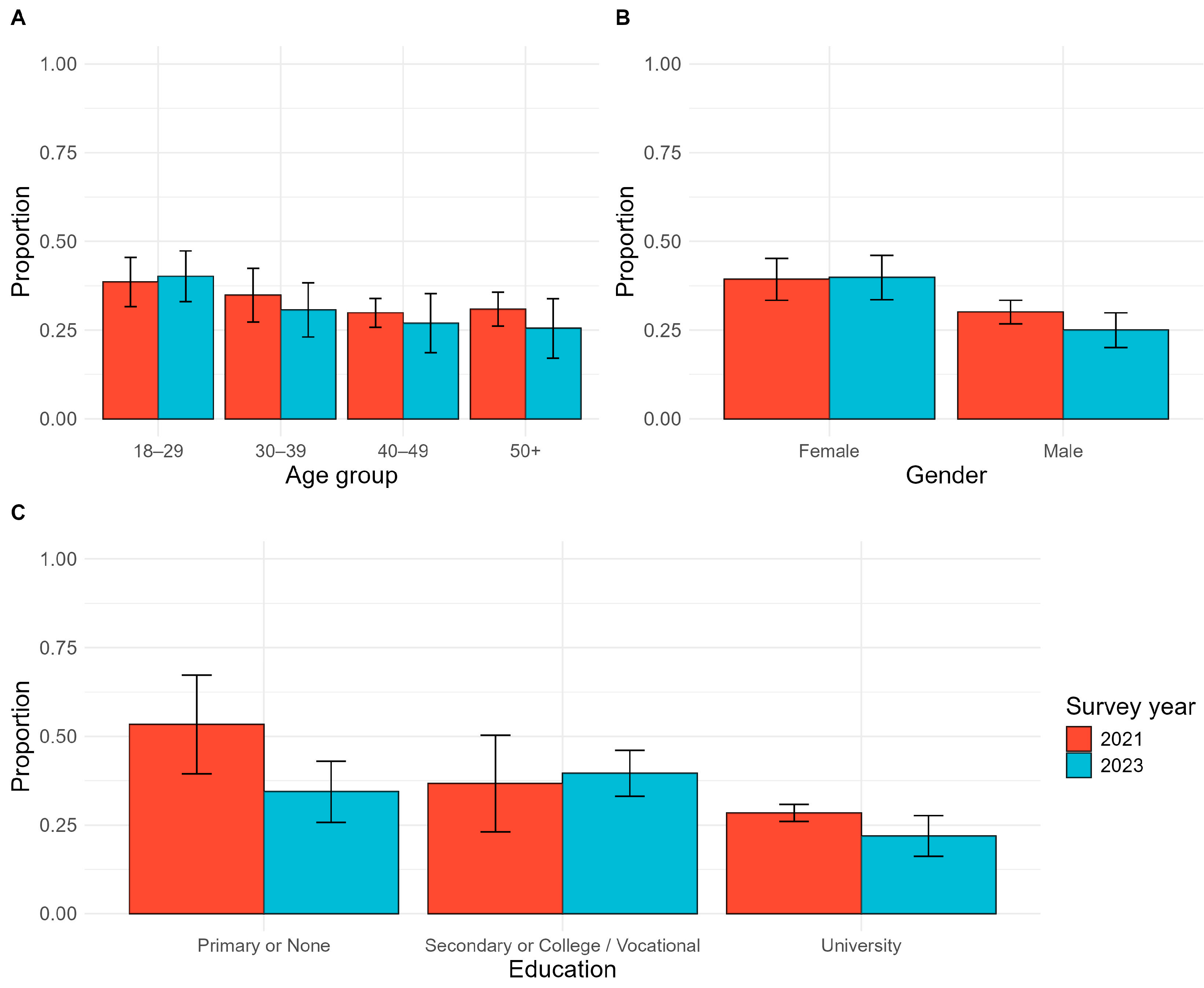

3.2.2. Vaccine Hesitancy

3.3. Exposure to Vaccine Promotion Activities

3.4. Trust in the Health System

3.5. Vaccine Acceptability

3.6. Risk Perception

3.7. Multivariable Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jamaluddine, Z.; Chen, Z.; Abukmail, H.; Aly, S.; Elnakib, S.; Barnsley, G.; Majorin, F.; Tong, H.; Igusa, T.; Campbell, O.M.R.; et al. Crisis in Gaza: Scenario-Based Health Impact Projections. Report One: 7 February to 6 August 2024; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Johns Hopkins University: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://aoav.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/gaza_projections_report.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- World Health Organization Occupied Palestinian Territory. oPt Emergency Situation Update—Issue 27 (7 October 2023–2 April 2024). Situation Report. 2 April 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/opt-emergency-situation-update-2apr24-who/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Beladiya, J.; Kumar, A.; Vasava, Y.; Parmar, K.; Patel, D.; Patel, S.; Dholakia, S.; Sheth, D.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Patel, C. Safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and randomized clinical trials. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link-Gelles, R.; Rowley, E.A.K.; DeSilva, M.B.; Dascomb, K.; Irving, S.A.; Klein, N.P.; Grannis, S.J.; Ong, T.C.; Weber, Z.A.; Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; et al. Interim Effectiveness of Updated 2023–2024 (Monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 Vaccines Against COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization among Adults Aged ≥18 Years with Immunocompromising Conditions—VISION Network, September 2023-February 2024. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.; Elhissi, J.H.; Mousa, N.; Kostandova, N. COVID-19 vaccination in the Gaza Strip: A cross-sectional study of vaccine coverage, hesitancy, and associated risk factors among community members and healthcare workers. Confl. Health 2022, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Leigh, J.P.; Hu, J.; El-Mohandes, A. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, Q.; Guo, X.; Shen, Z.; Tarimo, C.S.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Temporal changes in factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Chinese adults: Repeated nationally representative survey. SSM Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Chase, L.E.; Wagnild, J.; Akhter, N.; Sturridge, S.; Clarke, A.; Chowdhary, P.; Mukami, D.; Kasim, A.; Hampshire, K. Community health workers and health equity in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaniran, A.; Smith, H.; Unkels, R.; Bar-Zeev, S.; Broek, N.v.D. Who is a community health worker?—A systematic review of definitions. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1272223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, J.; Kaplan, L.C.; Sternberg, H. How to reduce vaccination hesitancy? The relevance of evidence and its communicator. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3964–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, A.; Stefanizzi, P.; Tafuri, S. Are we saying it right? Communication strategies for fighting vaccine hesitancy. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1323394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. Effective incentives for increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 3242–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Population Projections—Annual Statistics. Available online: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/803/default.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- CDC. Epi InfoTM 2022; Office of Public Health Data, Surveillance, and Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- UN-OCHA. KoboToolbox; UN-OCHA: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Lumley, T. “Survey: Analysis of complex survey samples”. R package version 4.4. or T. Lumley (2004) Analysis of complex survey samples. J. Stat. Softw. 2024, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg, D.D.; Whiting, K.; Curry, M.; Lavery, J.A.; Larmarange, J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the gtsummary Package. R J. 2021, 13, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (Palestine). Palestine Ministry of Health COVID-19 Surveillance System 2020–2022; Ministry of Health: Nablus, Palestine. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/palestine-ministry-health-covid-19-surveillance-system-2020-2022 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Li, C.; Islam, N.; Gutierrez, J.P.; Gutiérrez-Barreto, S.E.; Prado, A.C.; Moolenaar, R.L.; Lacey, B.; Richter, P. Associations of diabetes, hypertension and obesity with COVID-19 mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e012581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadogo, W.; Tsegaye, M.; Gizaw, A.; Adera, T. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for COVID-19-associated hospitalisations and death: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2022, 5, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Hamad, B.A.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Safadi, G.; Ragi, M.-E.; Ahmad, R.E.S.; Vamos, E.P.; Basu, S.; Yudkin, J.S.; Jawad, M.; Millett, C.; et al. The hypertension cascade of care in the midst of conflict: The case of the Gaza Strip. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2023, 37, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptoo, J.; Isiiko, J.; Yadesa, T.M.; Rhodah, T.; Alele, P.E.; Mulogo, E.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Assessing the prevalence, predictors, and effectiveness of a community pharmacy based counseling intervention. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K.; Civen, R.; Equils, O. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Misinformation and perceptions of vaccine safety. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1950504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desson, Z.; Kauer, L.; Otten, T.; Peters, J.W.; Paolucci, F. Finding the way forward: COVID-19 vaccination progress in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, V.; Keestra, S.M.; Hill, A. Global COVID-19 Vaccine Inequity: Failures in the First Year of Distribution and Potential Solutions for the Future. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 821117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M.; Gu, J.; Miao, Y.; Tarimo, C.S.; He, Y.; Xing, Y.; Ye, B. The pattern from the first three rounds of vaccination: Declining vaccination rates. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1124548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNRWA. UNRWA Situation Report #109 on the Situation in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, Including East Jerusalem. 24 May 2024. Available online: https://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/unrwa-situation-report-109-situation-gaza-strip-and-west-bank-including-east-Jerusalem (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Smith, L.E.; Amlôt, R.; Weinman, J.; Yiend, J.; Rubin, G.J. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6059–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reece, S.; CarlLee, S.; Scott, A.J.; Willis, D.E.; Rowland, B.; Larsen, K.; Holman-Allgood, I.; McElfish, P.A. Hesitant adopters: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among diverse vaccinated adults in the United States. Infect. Med. 2023, 2, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicken, A.; Jones, P.; Menon, A.; Rozek, L.S. Can endorsement by religious leaders move the needle on vaccine hesitancy? Vaccine 2024, 42, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Schmidt, B.-M.; Sambala, E.Z.; Swartz, A.; Colvin, C.J.; Leon, N.; Wiysonge, C.S. Factors that influence parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and practices regarding routine childhood vaccination: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, CD013265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavundza, E.J.; Cooper, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. A Systematic Review of Factors That Influence Parents’ Views and Practices around Routine Childhood Vaccination in Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Vaccines 2023, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenton, C.; Scheel, I.B.; Lewin, S.; Swingler, G.H. Can lay health workers increase the uptake of childhood immunisation? Systematic review and typology. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, P.; McCue, K.; Sabo, S.; Annorbah, R.; Jiménez, D.; Pilling, V.; Butler, M.; Celaya, M.F.; Rumann, S. Community health worker intervention improves early childhood vaccination rates: Results from a propensity-score matching evaluation. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafuri, S.; Gallone, M.S.; Cappelli, M.G.; Martinelli, D.; Prato, R.; Germinario, C. Addressing the anti-vaccination movement and the role of HCWs. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4860–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCready, J.L.; Nichol, B.; Steen, M.; Unsworth, J.; Comparcini, D.; Tomietto, M. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers and healthcare students worldwide: An Umbrella Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Ghazy, R.M.; Al-Salahat, K.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; AlHadidi, N.M.; Eid, H.; Kareem, N.; Al-Ajlouni, E.; Batarseh, R.; Ababneh, N.A.; et al. The Role of Psychological Factors and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs in Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy and Uptake among Jordanian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Outcome Measures and Determinants | Variable | Survey Question |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | ||

| Vaccination status | Vaccinated | “Have you already received the COVID-19 vaccine?” Adult members of the household 18 years or older who received at least one dose of any COVID-19 vaccine prior to the survey were classified as vaccinated. |

| Vaccine hesitancy | Vaccine hesitant: Lack of intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine | “If you could get a COVID-19 vaccine this week, would you get it?” Non-vaccinated individuals were classified as hesitant if they responded “no” or “unsure”, while all vaccinated individuals were classified as non-hesitant. |

| Exposure to vaccine promotion activities | ||

| Referral | Referred by a healthcare provider to take the vaccine | “Did IMC partner healthcare organizations or CBOs refer you to take the vaccine?” |

| Information | Received information from a healthcare provider about the vaccine | “Did you receive any information about the vaccine from IMC partner healthcare organizations or CBOs?” |

| Determinants | ||

| Demographic variables | Sex Age Governorate Highest level of education | Respondent gender (female/male/other/prefer not to say) Respondent age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+) Governorate (North, Gaza, Middle, Khan Younis, Rafah) “What is the highest educational grade/level that you have completed?” (none, primary, secondary, vocational, university) |

| Trust in the health system | Believe the health system can safely administer the vaccine to the population Health workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine Community health workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | “Do you think your health system can safely administer the COVID-19 vaccine to the population?” “Which source do you trust?” [to provide information about the COVID-19 vaccine] Respondents were asked to report yes/no for each of the following: HCWs at health clinics; CHWs; community leaders, radio, television, newspapers, mass events, and local leaders. |

| Vaccine acceptability | Considers vaccine safe or somewhat safe Concerned about the risk of side effects Believe there are better ways to prevent COVID-19 than vaccination Think it is better to get COVID-19 and develop natural immunity than to get the vaccine | “Do you consider the COVID-19 vaccines safe?” “Are you concerned about any risks or side effects with the COVID-19 vaccine?” “Do you believe that there are other (better) ways to prevent COVID-19 instead of the vaccine?” “Do you think it is better to get COVID-19 and develop natural immunity than to get the vaccine?” |

| Perceived risk | Self-perceived risk to get COVID-19 infection Self-perceived risk to develop severe disease following COVID-19 infection | “Do you think you are at risk to get COVID-19?” “Do you think you can get seriously ill, hospitalized or die if you get COVID-19?” |

| Variable | Frequency (N = 894) | % 1 (95% CI) 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 279 | 31.7 (27.8–35.6) |

| 30–39 | 230 | 24.4 (20.8–28.0) |

| 40–49 | 185 | 19.8 (16.3–23.3) |

| 50+ | 200 | 24.2 (20.3–28.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 365 | 45.0 (40.8–49.1) |

| Male | 528 | 55.0 (50.9–59.2) |

| Highest Education | ||

| Primary or None | 190 | 18.9 (15.7–22.2) |

| Secondary or College/Vocational | 347 | 41.9 (37.6–46.1) |

| University | 357 | 39.2 (35.0–43.4) |

| Governorate | ||

| Gaza | 317 | 34.2 (32.1–36.3) |

| Khan Younis | 172 | 19.8 (16.8–22.8) |

| Middle | 125 | 13.6 (10.4–16.8) |

| North | 176 | 20.0 (18.4–21.5) |

| Rafah | 104 | 12.5 (11.7–13.2) |

| Strata | ||

| Camp | 309 | 12.6 (10.9–14.3) |

| Rural | 104 | 4.5 (3.6–5.4) |

| Urban | 481 | 82.9 (80.9–84.9) |

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 894 | Camp, N = 309 | Rural, N = 104 | Urban, N = 481 | p-Value 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 1 | % (95% CI) 2 | n 1 | % (95% CI) 2 | n 1 | % (95% CI) 2 | n 1 | % (95% CI) 2 | ||

| Vaccine outcomes | |||||||||

| Received Vaccine | 597 | 63.5 (59.4–67.5) | 236 | 73.9 (68.1–79.7) | 71 | 71.2 (62.3–80.2) | 290 | 61.5 (56.7–66.3) | 0.001 |

| Vaccine Hesitant | 248 | 31.7 (27.8–35.6) | 56 | 18.5 (13.5–23.4) | 26 | 22.0 (13.8–30.1) | 166 | 34.2 (29.5–38.9) | <0.001 |

| Exposure to vaccine promotion by health workers | |||||||||

| Referred to get vaccine | 430 | 50.1 (45.8–54.4) | 147 | 43.8 (38.1–49.4) | 53 | 51.3 (41.1–61.6) | 230 | 51.0 (45.9–56.1) | 0.2 |

| Received information on vaccine | 514 | 58.5 (54.3–62.7) | 184 | 57.0 (50.8–63.1) | 61 | 62.4 (52.4–72.4) | 269 | 58.5 (53.6–63.5) | 0.7 |

| Trust in health system | |||||||||

| Believe the health system can safely administer the vaccine to the population | 770 | 82.3 (78.9–85.7) | 289 | 92.2 (88.2–96.2) | 98 | 92.1 (85.7–98.4) | 383 | 80.3 (76.3–84.3) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 683 | 76.7 (73.3–80.0) | 250 | 82.3 (77.5–87.1) | 90 | 87.8 (81.2–94.4) | 343 | 75.2 (71.3–79.2) | 0.005 |

| Community health workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 338 | 37.1 (33.2–40.9) | 109 | 42.4 (36.5–48.2) | 51 | 56.8 (47.0–66.6) | 178 | 35.2 (30.6–39.8) | <0.001 |

| Vaccine acceptability | |||||||||

| Considers vaccine safe or somewhat safe | 673 | 72.9 (69.1–76.6) | 253 | 80.7 (75.6–85.8) | 80 | 77.6 (69.2–86.0) | 340 | 71.4 (67.0–75.9) | 0.015 |

| Concerned about risk of side effects | 627 | 70.4 (66.6–74.1) | 227 | 72.9 (67.3–78.4) | 79 | 75.3 (66.3–84.3) | 321 | 69.7 (65.3–74.2) | 0.4 |

| Believe there are better ways to prevent COVID-19 than vaccination | 500 | 63.9 (59.9–67.9) | 119 | 40.6 (34.6–46.6) | 58 | 49.7 (39.5–59.8) | 323 | 68.2 (63.6–72.8) | <0.001 |

| Think it is better to get COVID-19 and develop natural immunity than to get the vaccine | 551 | 68.1 (64.0–72.1) | 129 | 48.5 (42.4–54.6) | 73 | 67.6 (57.9–77.2) | 349 | 71.0 (66.3–75.8) | <0.001 |

| Risk perception | |||||||||

| Think you are at risk to get COVID-19 | 711 | 76–83 | 266 | 88.6 (85.1–92.2) | 80 | 84.3 (78.3–90.3) | 365 | 78.1 (74.3–81.9) | <0.001 |

| Think you can get seriously ill, hospitalized, or die if you get COVID-19 | 253 | 30–38 | 55 | 23.7 (17.7–29.8) | 27 | 29.8 (20.1–39.5) | 171 | 36.0 (31.2–40.8) | 0.005 |

| Characteristic | Unadjusted (N = 894) | Adjusted (N = 876) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | 95% CI | p-Value | aOR 2 | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Exposure to vaccine promotion by health workers | ||||||

| Referred to get vaccine | 5.58 | 3.79, 8.21 | <0.001 | 4.20 | 2.59, 6.83 | <0.001 |

| Received information on vaccine | 4.20 | 2.88, 6.12 | <0.001 | — | — | — |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex | 0.001 | |||||

| Female | — | — | — | — | ||

| Male | 1.80 | 1.27, 2.57 | 1.80 | 1.12, 2.91 | 0.016 | |

| Age | 0.006 | |||||

| 18–39 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 40+ | 1.68 | 1.16, 2.43 | 1.87 | 1.10, 3.18 | 0.021 | |

| Highest education | <0.001 | |||||

| Primary or None | — | — | — | — | ||

| Secondary or College/Vocational | 0.69 | 0.43, 1.09 | 0.78 | 0.39, 1.53 | 0.46 | |

| University | 1.74 | 1.07, 2.84 | 2.81 | 1.42, 5.54 | 0.003 | |

| Trust in health system | ||||||

| Believe the health system can safely administer the vaccine to the population | 4.25 | 2.49, 7.27 | <0.001 | |||

| Healthcare workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 2.69 | 1.83, 3.96 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 1.02, 3.39 | 0.044 |

| Community health workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 1.71 | 1.18, 2.47 | 0.004 | |||

| Vaccine acceptability | ||||||

| Considers vaccine safe or somewhat safe | 16.4 | 9.55, 28.0 | <0.001 | 16.1 | 8.88, 29.2 | <0.001 |

| Concerned about risk of side effects | 0.32 | 0.21, 0.49 | <0.001 | |||

| Believe there are better ways to prevent COVID-19 than vaccination | 0.16 | 0.10, 0.24 | <0.001 | |||

| Think it is better to get COVID-19 and develop natural immunity than to get the vaccine | 0.14 | 0.08, 0.25 | <0.001 | |||

| Risk perception | ||||||

| Think you are at risk to get COVID-19 | 1.36 | 0.89, 2.06 | 0.15 | |||

| Think you can get seriously ill, hospitalized, or die if you get COVID-19 | 1.38 | 0.94, 2.02 | 0.10 | 1.75 | 1.01, 3.02 | 0.045 |

| Characteristic | Unadjusted (N = 894) | Adjusted (N = 873) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | 95% CI | p-Value | aOR 2 | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Exposure to vaccine promotion by health workers | ||||||

| Referred to get vaccine | 0.17 | 0.11, 0.25 | <0.001 | — | — | — |

| Received information on vaccine | 0.23 | 0.16, 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.20, 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Female | — | — | — | — | ||

| Male | 0.50 | 0.35, 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.30, 0.83 | 0.007 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–39 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 40+ | 0.63 | 0.43, 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.34, 1.15 | 0.13 | |

| Highest education | <0.001 | |||||

| Primary or None | — | — | — | — | ||

| Secondary or College/Vocational | 1.25 | 0.78, 2.01 | 1.26 | 0.60, 2.65 | 0.53 | |

| University | 0.54 | 0.32, 0.89 | 0.41 | 0.20, 0.87 | 0.021 | |

| Trust in health system | ||||||

| Believe the health system can safely administer the vaccine to the population | 0.22 | 0.13, 0.38 | <0.001 | |||

| Healthcare workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 0.33 | 0.22, 0.48 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 0.20, 0.72 | 0.003 |

| Community health workers are a trusted source of information on the vaccine | 0.44 | 0.29, 0.66 | <0.001 | |||

| Vaccine acceptability | ||||||

| Considers vaccine safe or somewhat safe | 0.06 | 0.04, 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.04, 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Concerned about risk of side effects | 3.08 | 1.94, 4.91 | <0.001 | |||

| Believe there are better ways to prevent COVID-19 than vaccination | 7.56 | 4.69, 12.2 | <0.001 | |||

| Think it is better to get COVID-19 and develop natural immunity than to get the vaccine | 6.49 | 3.47, 12.2 | <0.001 | |||

| Risk perception | ||||||

| Think you are at risk to get COVID-19 | 0.64 | 0.41, 0.98 | 0.039 | |||

| Think you can get seriously ill, hospitalized, or die if you get COVID-19 | 0.75 | 0.50, 1.11 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.30, 1.00 | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majer, J.; Elhissi, J.H.; Mousa, N.; John-Kall, J.; Kostandova, N. COVID-19 Vaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy in the Gaza Strip from a Cross-Sectional Survey in 2023: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Associations with Health System Interventions. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12101098

Majer J, Elhissi JH, Mousa N, John-Kall J, Kostandova N. COVID-19 Vaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy in the Gaza Strip from a Cross-Sectional Survey in 2023: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Associations with Health System Interventions. Vaccines. 2024; 12(10):1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12101098

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajer, Jennifer, Jehad H. Elhissi, Nabil Mousa, Jill John-Kall, and Natalya Kostandova. 2024. "COVID-19 Vaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy in the Gaza Strip from a Cross-Sectional Survey in 2023: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Associations with Health System Interventions" Vaccines 12, no. 10: 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12101098