Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Indonesia: Lessons from Multi-Site Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Development of the Questionnaire

2.2. Data Collection and Study Sites

2.3. Variable Definition and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

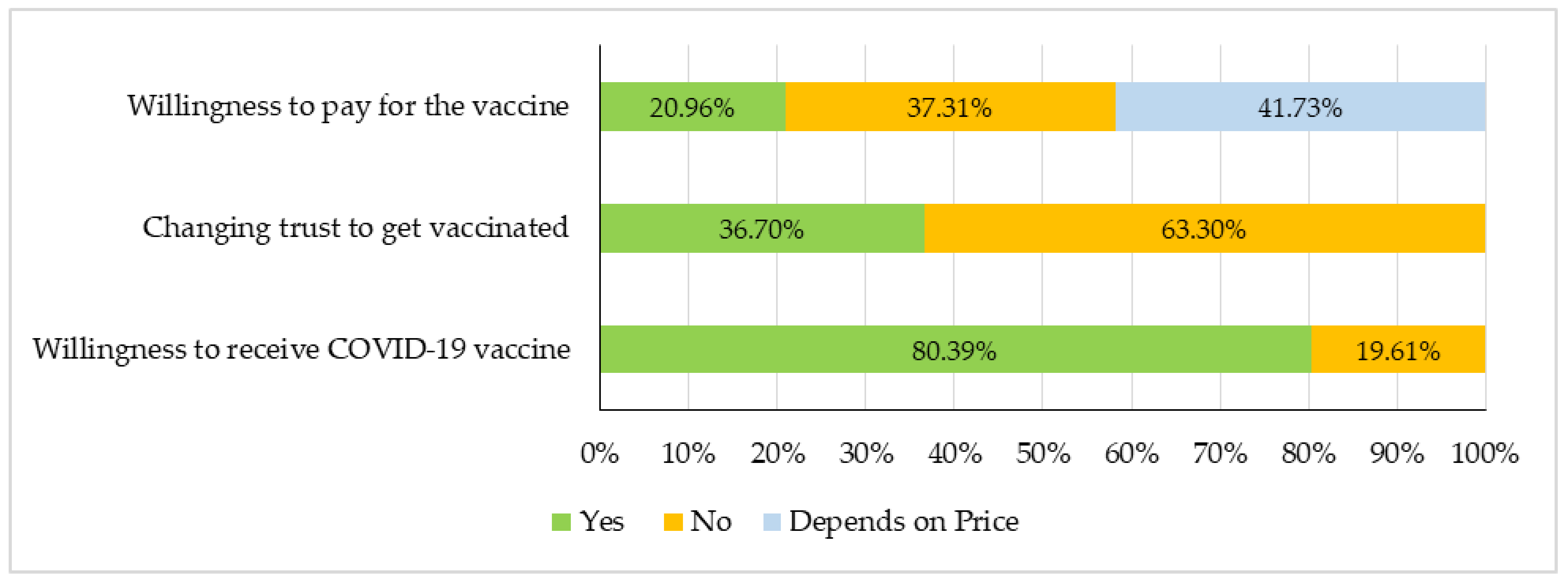

3.2. Willingness to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine and Trust in the Vaccination Programs

3.3. Reasons for Not Being Willing to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine

3.4. Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with the COVID-19 Vacciation Decision

3.5. Attitude of Healthcare Workers towards the COVID-19 Vaccine and Vaccination

3.6. Other Factors Associated with the COVID-19 Vaccination Decision

3.7. Sources of Information on COVID-19, COVID-19 Vaccines and Vaccination, and Suitable Platforms for Communication

3.8. Information to Be Communicated for COVID-19 Vaccine Introduction in Indonesia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Livelihoods, Their Health and Our Food Systems. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people’s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: Overview. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. New COVID-19 Cases Worldwide. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Health Emergency Dashboard: COVID-19. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/id (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Purvis, R.S.; Moore, R.; Willis, D.E.; Hallgren, E.; McElfish, P.A. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine decision-making among hesitant adopters in the United States. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2114701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D.; Meyer-Weitz, A.; Govender, K. Factors Influencing the Intention and Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines on the African Continent: A Scoping Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Sami, W.; Alam, Z.; Acharya, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Songwathana, K.; Pham, N.T.; Respati, T.; Faller, E.M.; Baldonado, A.M.; et al. Hesitancy in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated factors among the general adult population: A cross-sectional study in six Southeast Asian countries. Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawas, G.T.; Zeidan, R.S.; Edwards, C.A.; El-Desoky, R.H. Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccines and Strategies to Improve Acceptability and Uptake. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 36, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, T.; Shiroma, K.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Xie, B.; Jia, C.; Verma, N.; Lee, M.K. Misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 2023, 41, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Sun, J.; Jang, S.; Connelly, S. Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Lima, G.; Cha, M.; Cha, C.; Kulshrestha, J.; Ahn, Y.-Y.; Varol, O. Misinformation, believability, and vaccine acceptance over 40 countries: Takeaways from the initial phase of the COVID-19 infodemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Nkambule, S.J.; Hlongwa, M.; Mhango, M.; Iradukunda, P.G.; Chitungo, I.; Dzobo, M.; Mapingure, M.P.; Chingombe, I.; Mashora, M.; et al. Risk Factors for COVID-19 Infection Among Healthcare Workers. A First Report from a Living Systematic Review and meta-Analysis. Saf. Health Work. 2022, 13, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO SAGE Roadmap for Prioritizing Uses of COVID-19 Vaccines: An Approach to Optimize the Global Impact of COVID-19 Vaccines, Based on Public Health Goals, Global and National Equity, and Vaccine Access and Coverage Scenarios. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-Vaccines-SAGE-Prioritization-2022.1 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Brauer, E.; Choi, K.; Chang, J.; Luo, Y.; Lewin, B.; Munoz-Plaza, C.; Bronstein, D.; Bruxvoort, K. Health Care Providers’ Trusted Sources for Information About COVID-19 Vaccines: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Infodemiology 2021, 1, e33330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, M.T.; De Giglio, O.; Napoli, C.; Fasano, F.; Diella, G.; Donnoli, R.; Caggiano, G.; Tafuri, S.; Lopalco, P.L.; Agodi, A.; et al. Adherence to Vaccination Policy among Public Health Professionals: Results of a National Survey in Italy. Vaccines 2020, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.J.; Lee, B.; Nugent, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers—A review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noushad, M.; Rastam, S.; Nassani, M.Z.; Al-Saqqaf, I.S.; Hussain, M.; Yaroko, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Kirfi, A.M.; Koppolu, P.; Niazi, F.H.; et al. A Global Survey of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Healthcare Workers. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 794673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awaidy, S.T.; Al Siyabi, H.; Khatiwada, M.; Al Siyabi, A.; Al Mukhaini, S.; Dochez, C.; Giron, D.M.; Langrial, S.U.; Mahomed, O. Assessing COVID-19 Vaccine’s Acceptability Amongst Health Care Workers in Oman: A cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Schulz, W.S.; Chaudhuri, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dubé, E.; Schuster, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Wilson, R.; The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, R.; Narendran, M.; Bindu, A.; Beevi, N.; Manju, L.; Benny, P.V. Public perception and preparedness for the pandemic COVID-19: A health belief model approach. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO; Ministry of Health; NITAG; Indonesia Report. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Survey in Indonesia. 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/media/7631/file/COVID-19%20Vaccine%20Acceptance%20Survey%20in%20Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Laranjo, L. Chapter 6—Social Media and Health Behavior Change. In Participatory Health Through Social Media; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.W.C.; Liow, Y.; Loh, V.W.K.; Liew, S.J.; Chan, Y.-H.; Young, D. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among primary healthcare workers in Singapore. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.M.; Ismail, S.A.; Ojo-Aromokudu, O.; Naqvi, H.; Coghill, Y.; Donovan, H.; Letley, L.; Paterson, P.; Mounier-Jack, S. COVID-19 vaccination beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours among health and social care workers in the UK: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, N.J.; Tfaily, N.K.; Moumneh, M.B.M.; Boutros, C.F.; Elharake, J.A.; Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Galal, B.; Yildirim, I.; Khoshnood, K.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy Among Health Care Workers in Lebanon. J. Epidemiology Glob. Health 2023, 13, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Dauby, N.; Adedzi, K.A.; Gobert, C.; Bergeat, M.; Gagneur, A.; Dubé, E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: A survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2002047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudenda, S.; Daka, V.; Matafwali, S.K.; Skosana, P.; Chabalenge, B.; Mukosha, M.; Fadare, J.O.; Mfune, R.L.; Witika, B.A.; Alumeta, M.G.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Lusaka, Zambia; Findings and Implications for the Future. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzaji, M.K.; Kamenga, J.D.D.; Lungayo, C.L.; Bene, A.C.M.; Meyou, S.F.; Kapit, A.M.; Fogarty, A.S.; Sessoms, D.; MacDonald, P.D.; Standley, C.J.; et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Hamayoun, M.; Farid, M.; Al-Umra, U.; Shube, M.; Sumaili, K.; Shamalla, L.; Malik, S.M.M.R. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy in Health Care Workers in Somalia: Findings from a Fragile Country with No Previous Experience of Mass Adult Immunization. Vaccines 2023, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieurin, J.; Brandén, G.; Magnusson, C.; Hergens, M.-P.; Kosidou, K. A population-based cohort study of sex and risk of severe outcomes in covid-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Circular Letter Number:, HK.01.07/Menkes/169/2020 Regarding the Designation of Referral Hospitals for the Management of Certain Emerging Infectious Diseases (In Indonesian: Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor HK.01.07/Menkes/169/2020 Tentang Penetapan Rumah Sakit Rujukan Penanggulangan Penyakit Infeksi Emerging Tertentu). 2020. Available online: https://setkab.go.id/menkes-tetapkan-132-rs-rujukan-penanggulangan-penyakit-infeksi-emerging-tertentu/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Office of the Assistant to Deputy Cabinet Secretary for State Documents & Translation. Gov’t to Use Certified Halal Vaccines for Muslims. 2022. Available online: https://setkab.go.id/en/govt-to-use-certified-halal-vaccines-for-muslims/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Machmud, P.B.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Gottschick, C. Understanding hepatitis B vaccination willingness in the adult population in Indonesia: A survey among outpatient and healthcare workers in community health centers. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiwada, M.; Nugraha, R.R.; Harapan, H.; Dochez, C.; Mutyara, K.; Rahayuwati, L.; Syukri, M.; Wardoyo, E.H.; Suryani, D.; Que, B.J.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Indonesia. Going Digital to Boost Children’s Immunization. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/health/stories/going-digital-to-boost-childrens-immunization#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Ministry%20of,Aceh%20received%20complete%20basic%20immunization.&text=Mohd%20Ichsan%2C%20a%20Data%20Coordinator,data%20gathered%20in%20the%20field (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Vo, T.Q.; et al. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indonesian Ministry of Health. The Decree of the General Directorate of Infection Prevention and Control MoH no. HK.02.02/4/1/2021 on Technical Guidelines of Vaccination for Management of the Corona Virus Disease Pandemic 2019 (COVID-19); Indonesian Ministry of Health: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portoghese, I.; Siddi, M.; Chessa, L.; Costanzo, G.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Perra, A.; Littera, R.; Sambugaro, G.; Del Giacco, S.; Campagna, M.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Italian Healthcare Workers: Latent Profiles and Their Relationships to Predictors and Outcome. Vaccines 2023, 11, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Concerns, Attitudes, and Intended Practices of Healthcare Workers toward COVID-19 Vaccination in the Caribbean. Document Number: PAHO/CPC/COVID-19/21-0001. 2021. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/54964 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Paterson, P.; Meurice, F.; Stanberry, L.R.; Glismann, S.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6700–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Coppeta, L.; Olesen, O.F. Vaccine Hesutancy among Healthcare workers in Europe: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Kagan, N.; Critchlow, C.; Hillard, A.; Hsu, A. The Danger of Misinformation in the COVID-19 Crisis. Mo. Med. 2020, 117, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Socio-Demographic Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Province (University) | ||

| Jawa Barat (West Java) | 1140 | 41.9 |

| Aceh | 764 | 28.0 |

| Nusa Tenggara Barat (West Nusa Tenggara) | 460 | 16.9 |

| Maluku | 360 | 13.2 |

| Educational Level | ||

| Bachelors/MD degree | 1702 | 63.0 |

| Diploma | 502 | 18.6 |

| Doctorate | 48 | 1.8 |

| Masters | 289 | 10.7 |

| Sub-Specialists | 47 | 1.7 |

| Others | 112 | 4.1 |

| Job Title | ||

| Physician | 1498 | 55.0 |

| Nurse/Nursing staff | 896 | 32.9 |

| Pharmacist | 27 | 1.0 |

| Midwives | 94 | 3.4 |

| Others (clinical psychologist, medical technician, public health staff, nutritionist, physical therapists) | 211 | 7.7 |

| Healthcare facility type | ||

| Primary care (private practice, clinics, primary health care (puskesmas, posbindu, emergency facilities), treatment center, delivery home) | 2016 | 74.0 |

| Secondary care (hospitals including emergency hospitals, both public-owned and private) | 434 | 16.0 |

| Others | 271 | 10.0 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 158 | 5.8 |

| 26–35 | 1637 | 60.5 |

| 36–45 | 643 | 23.7 |

| 46–55 | 196 | 7.2 |

| 56–65 | 74 | 2.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1063 | 39.3 |

| Female | 1643 | 60.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 697 | 25.8 |

| Married | 2008 | 74.2 |

| Religion | ||

| Islam | 2184 | 80.7 |

| Hinduism | 85 | 3.1 |

| Christianity | 424 | 15.7 |

| Buddhism | 12 | 0.4 |

| Others | 2 | 0.1 |

| Average monthly household expenditure (Indonesian Rupiah) | ||

| ˂1 million | 64 | 2.4 |

| 1- < 5 million | 1105 | 40.9 |

| 5- < 10 million | 916 | 33.9 |

| 10- < 20 million | 284 | 10.5 |

| ≥20 million | 90 | 3.3 |

| Prefer not to say | 242 | 9.0 |

| Type of health insurance you/your family have | ||

| National health insurance | 2240 | 82.4 |

| Personal/private insurance | 77 | 2.8 |

| Both insurance | 272 | 10.0 |

| No insurance | 128 | 4.8 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine Yes/No n (%) | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine Yes vs. No | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-Value | OR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Province (N = 2695) | ||||

| Jawa Barat | 1032 (91.3)/98 (8.7) | 0.84 | <0.001 ** | 2.32 (1.69–3.18) |

| Aceh | 455 (60.7)/295 (39.3) | −1.07 | <0.001 ** | 0.34 (0.26–0.45) |

| Maluku | 309 (86.8)/47 (13.2) | 0.37 | 0.06 | 1.45 (0.98–2.14) |

| Nusa Tenggara Barat | 376 (81.9)/83 (18.1) | Ref | ||

| Educational Level (N = 2671) | ||||

| Bachelors/MD Degree | 1367 (81.0)/320 (19.0) | Ref | ||

| Diploma | 371 (75.1)/123 (24.9) | −0.35 | 0.004 ** | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) |

| Doctorate (PhD) | 43 (91.5)/4 (8.5) | 0.92 | 0.08 | 2.52 (0.90–7.06) |

| Masters/Specialty | 250 (87.7)/35 (12.3) | 0.51 | 0.007 * | 1.67 (1.15–2.43) |

| Others | 83 (74.1)/29 (25.9) | −0.40 | 0.07 | 0.67 (0.43–1.04) |

| Sub-Specialists | 38 (74.1)/8 (17.4) | 0.11 | 0.79 | 1.11 (0.51–2.40) |

| Job Title (N = 2698) | ||||

| Physician | 1263 (85.0)/223 (15.0) | 0.43 | 0.10 | 1.53 (0.91–2.56) |

| Nurse/Nursing staff | 640 (72.4)/244 (27.6) | −0.34 | 0.19 | 0.71 (0.42–1.19) |

| Pharmacist | 20 (76.9)/6 (23.1) | −0.10 | 0.84 | 0.90 (0.32–2.54) |

| Others | 175 (84.1)/33 (15.9) | 0.36 | 0.25 | 1.43 (0.77–2.66) |

| Midwives | 74 (78.7)/20 (21.3) | Ref | ||

| Healthcare facility type (N = 2694) | ||||

| Primary care | 1572 (78.6)/429 (21.4) | −0.52 | 0.005 * | 0.59 (0.41–0.85) |

| Secondary care | 368 (86.0)/60 (14.0) | −0.005 | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.64–1.55) |

| Others | 228 (86.0)/37 (14.0) | Ref | ||

| Age (N = 2678) | ||||

| 18–25 | 128 (81.5)/29 (18.5) | −0.44 | 0.28 | 0.64 (0.29–1.44) |

| 26–35 | 1317 (81.1)/306 (18.9) | −0.47 | 0.19 | 0.62 (0.31–1.27) |

| 36–45 | 495 (78.0)/140 (22.0) | −0.67 | 0.07 | 0.51 (0.25–1.06) |

| 46–55 | 155 (80.7)/37 (19.3) | −0.50 | 0.21 | 0.61 (0.28–1.33) |

| 56–65 | 62 (87.3)/9 (12.7) | Ref | ||

| Gender (N = 2678) | ||||

| Male | 898 (85.4)/154 (14.6) | 0.53 | <0.001 ** | 1.70 (1.38–2.09) |

| Female | 1259 (77.4)/367 (22.6) | Ref | ||

| Marital status (N = 2676) | ||||

| Single | 578 (83.4)/115 (16.6) | 0.26 | 0.03 * | 1.29 (1.03–1.62) |

| Married | 1577 (79.5)/406 (20.5) | Ref | ||

| Religion (N = 2678) | ||||

| Islam | 1681 (77.9)/478 (22.1) | Ref | ||

| Hinduism | 80 (95.2)/4 (4.8) | 1.282 | <0.001 ** | 5.69 (2.07–15.60) |

| Christianity | 382 (90.7)/39 (9.3) | 1.02 | <0.001 ** | 2.78 (1.97–3.93) |

| Others | 14 (100.0)/0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Monthly household expenditure (N = 2673) | ||||

| Low | 45 (72.6)/17 (27.4) | Ref | ||

| Medium | 1607 (80.3)/395 (19.7) | 0.43 | 0.14 | 1.54 (0.87–2.71) |

| High | 315 (84.7)/57 (15.3) | 0.74 | 0.02 * | 2.09 (1.12–3.90) |

| Prefer not to say | 186 (78.5)/51 (21.5) | 0.32 | 0.32 | 1.38 (0.73–2.61) |

| Type of health insurance (N = 2688) | ||||

| National health insurance | 1757 (79.4)/455 (20.6) | −0.06 | 0.78 | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) |

| Private health insurance | 68 (88.3)/9 (11.7) | 0.61 | 0.15 | 1.83 (0.81–4.17) |

| Both insurance | 238 (87.8)/33 (12.2) | 0.56 | 0.054 | 1.75 (0.99–3.09) |

| No insurance | 103 (80.5)/25 (19.5) | Ref | ||

| Characteristics | Frequency | Willingness to Get Vaccinated | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine: Yes vs. No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Infected with SARS-CoV-2 (N = 2698) | ||||||

| Yes | 370 | 239 (64.6) | 131 (35.4) | 0.98 | <0.001 ** | 2.68 (2.11–3.40) |

| No | 2328 | 1933 (83.0) | 395 (17.0) | Ref | ||

| Contacts with suspected COVID-19 patients at work (N = 2685) | ||||||

| Yes | 2353 | 1898 (80.7) | 455 (19.3) | −0.05 | 0.71 | 0.95 (0.71–1.26) |

| No | 332 | 265 (79.8) | 67 (20.2) | Ref | ||

| Have chronic disease (N= 2663) | ||||||

| Yes | 442 | 317 (71.7) | 125 (28.3) | 0.62 | <0.001 ** | 1.85 (1.46–2.34) |

| No | 2221 | 1831 (82.4) | 390 (17.6) | Ref | ||

| Received Flu vaccine during the last 5 years (N = 2679) | ||||||

| Yes | 522 | 458 (87.7) | 64 (12.3) | 0.65 | <0.001 ** | 1.92 (1.45–2.55) |

| No | 2157 | 1700 (78.8) | 457 (21.2) | Ref | ||

| Treating COVID-19 patients (N = 2692) | ||||||

| Yes | 1699 | 1368 (80.5) | 331 (19.5) | 0.003 | 0.98 | 1.003 (0.82–1.22) |

| No | 993 | 800 (80.6) | 193 (19.4) | Ref | ||

| Recommend your patients take the COVID-19 vaccine (N = 2552) | ||||||

| Yes | 2050 | 1881 (91.8) | 169 (8.2) | 2.87 | <0.001 ** | 17.67 (13.92–22.44) |

| No | 502 | 194 (38.6) | 308 (61.4) | Ref | ||

| Recommend your family members and friends take the COVID-19 vaccine (N = 2552) | ||||||

| Yes | 2015 | 1904 (94.5) | 111 (5.5) | 3.59 | <0.001 ** | 36.40 (27.97–47.38) |

| No | 537 | 172 (32.0) | 365 (68.0) | Ref | ||

| Belief towards vaccines and vaccination changed after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (N = 2550) | ||||||

| Yes | 935 | 779 (83.3) | 156 (16.7) | 0.21 | 0.051 | 1.23 (0.99–1.52) |

| No | 1615 | 1295 (80.2) | 320 (19.8) | Ref | ||

| Awareness of phase III COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial in Indonesia (N = 2555) | ||||||

| Yes | 2132 | 1803 (84.6) | 329 (15.4) | 1.12 | <0.001 ** | 3.07 (2.44–3.87) |

| No | 423 | 271 (64.1) | 152 (35.9) | Ref | ||

| Characteristics | Frequencyn (%) | Willingness to Be Vaccinated | Intent to Be Vaccinated: Yes vs. No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Vaccine Efficacy (N = 2677) | ||||||

| I would take the COVID-19 vaccine if it is ≥80% effective. | 1717 (64.1) | 1333 (77.6) | 384 (22.4) | 1.59 | 0.001 ** | 4.90 (3.30–7.28) |

| I would like to take the COVID-19 vaccine if it is even 50–80% effective. | 584 (21.8) | 551 (94.3) | 33 (5.7) | 3.16 | <0.001 ** | 23.59 (14.09–39.52) |

| I would take the COVID-19 vaccine irrespective of the vaccine efficacy data. | 265 (9.9) | 228 (86.0) | 37 (14.0) | 3.66 | <0.001 ** | 8.70 (5.21–14.55) |

| Others | 111 (4.2) | 46 (41.4) | 65 (58.6) | Ref | ||

| Number of doses (N = 2650) | ||||||

| I would consider the number of doses as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 1957 (73.8) | 1634 (83.5) | 323 (16.5) | 0.65 | <0.001 ** | 1.92 (1.57–2.36) |

| I would not consider the number of doses as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 693 (26.2) | 502 (72.4) | 191 (27.6) | Ref | ||

| Willingness to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine (estimated price: IDR 200,000–IDR 500,000) (N = 2551) | ||||||

| Yes | 537 (21.1) | 500 (93.1) | 37 (6.9) | 2.02 | <0.001 ** | 7.52 (5.25–10.78) |

| Depends on the actual vaccine price. | 1069 (41.9) | 964 (90.2) | 105 (9.8) | 1.63 | <0.001 ** | 5.11 (4.02–6.51) |

| No | 945 (37.0) | 607 (64.2) | 338 (35.8) | Ref | ||

| Statements | Intent to Be Vaccinated: Yes vs. No | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | |

| All my activities will be disrupted if I get infected with SARS-CoV-2. | 0.54 | 0.02 * | 1.72 (1.06–2.78) |

| COVID-19 is a serious disease for me. | 0.99 | 0.001 ** | 2.71 (1.47–4.97) |

| COVID-19 is a serious disease for my family. | 1.42 | <0.001 ** | 4.14 (1.87–9.12) |

| The COVID-19 vaccine is the most effective tool to prevent COVID-19. | 2.28 | <0.001 ** | 9.82 (7.23–13.33) |

| I decided to be vaccinated because my workplace suggested so. | 1.92 | <0.001 ** | 6.81 (5.07–9.16) |

| I decided to be vaccinated because a close friend contracted COVID-19. | 2.13 | <0.001 ** | 8.39 (5.88–11.96) |

| I decided to be vaccinated because studies will prove the long-term safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination. | 3.07 | <0.001 ** | 21.53 (15.42–30.13) |

| One of the ways to prevent COVID-19 complications is through COVID-19 vaccination. | 3.31 | <0.001 ** | 27.52 (19.00–39.84) |

| I do not like injections in general. | −1.10 | <0.001 ** | 0.33 (0.26–0.42) |

| I am worried about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine. | −2.76 | <0.001 ** | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) |

| I do not need the COVID-19 vaccine because I am healthy. | −3.78 | <0.001 ** | 0.023 (0.016–0.033) |

| I am worried there will be side effects after COVID-19 vaccination. | −2.28 | <0.001 ** | 0.10 (0.06–0.18) |

| I prefer not to get vaccinated because of my religious beliefs. | −3.68 | <0.001 ** | 0.025 (0.018–0.036) |

| I believe that natural COVID-19 disease prevention is better than vaccination. | −3.10 | <0.001 ** | 0.045 (0.032–0.064) |

| I might still get COVID-19 even when I am vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine. | −1.43 | <0.001 ** | 0.24 (0.16–0.34) |

| My government provides transparent and up-to-date information on COVID-19 vaccine development and its introduction. | 2.25 | <0.001 ** | 9.46 (7.05–12.69) |

| I value the importance of vaccines and vaccination more now, after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. | 2.79 | <0.001 ** | 16.33 (10.54–25.30) |

| I valued the importance of vaccines and vaccination before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic as well. | 2.27 | <0.001 ** | 9.66 (6.47–14.45) |

| Information Sources | Mean Score |

|---|---|

| The rank of the main sources of information | |

| Social media (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter) | 2.27 |

| Radio, Newspaper, Television | 3.00 |

| Scientific Journals | 3.48 |

| Workplace | 3.59 |

| Ministry of Health and COVID-19 Task Force Website | 4.07 |

| Fellow Colleagues | 4.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khatiwada, M.; Nugraha, R.R.; Dochez, C.; Harapan, H.; Mutyara, K.; Rahayuwati, L.; Syukri, M.; Wardoyo, E.H.; Suryani, D.; Que, B.J.; et al. Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Indonesia: Lessons from Multi-Site Survey. Vaccines 2024, 12, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12060654

Khatiwada M, Nugraha RR, Dochez C, Harapan H, Mutyara K, Rahayuwati L, Syukri M, Wardoyo EH, Suryani D, Que BJ, et al. Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Indonesia: Lessons from Multi-Site Survey. Vaccines. 2024; 12(6):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12060654

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhatiwada, Madan, Ryan Rachmad Nugraha, Carine Dochez, Harapan Harapan, Kuswandewi Mutyara, Laili Rahayuwati, Maimun Syukri, Eustachius Hagni Wardoyo, Dewi Suryani, Bertha J. Que, and et al. 2024. "Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Indonesia: Lessons from Multi-Site Survey" Vaccines 12, no. 6: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12060654

APA StyleKhatiwada, M., Nugraha, R. R., Dochez, C., Harapan, H., Mutyara, K., Rahayuwati, L., Syukri, M., Wardoyo, E. H., Suryani, D., Que, B. J., & Kartasasmita, C. (2024). Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Indonesia: Lessons from Multi-Site Survey. Vaccines, 12(6), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12060654