Abstract

Background/Objectives: As zero-dose vaccination has become a global health concern, understanding the practice of self-paid immunizations in migrant and left-behind children in China is crucial to the prevention and control of infectious diseases. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in 1648 children and their caregivers in urban areas in Zhejiang Province and rural areas in Henan Province. The participants were then classified into four groups: urban local, migrant, non-left-behind, and left-behind. Results: Compared to urban local children, migrant (prevalence ratios: 1.29, 95% confidence intervals: 0.69–2.41), non-left-behind (4.72, 3.02–7.37), and left-behind (4.79, 3.03–7.56) children were more likely to be zero-dose vaccinated. Children aged 1–2 years (odds ratio: 1.60, 95% confidence intervals: 1.14–2.23) and born later (1.55, 1.12–2.14), with caregivers aged >35 years (1.49, 1.03–2.15) and less educated (elementary school or lower: 4.22, 2.39–7.45) were less likely to receive self-paid vaccinations, while caregivers other than parents (0.62, 0.41–0.94) and lower household income (0.67, 0.49–0.90) lowered the likelihood of zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines. For migrant and rural zero-dose children, the majority of caregivers reported they “didn’t know where to get a vaccination”, with responses ranging from 82.3% to 93.8%. Conclusions: Migrant and rural children should be prioritized in the promotion of self-paid immunization in order to accomplish the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030’s goal of “leaving no one behind”.

1. Introduction

Since the establishment of the National Immunization Program (NIP) in 1978, China has made enormous progress in the control of infectious diseases [1], with over 16 million infants vaccinated each year [2]. Despite the strong recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO), there are still a few vaccines to prevent infectious diseases that have not been included in the NIP in China [3]. These vaccines are voluntary and self-paid, contributing to wide vaccine inequity, with a considerable proportion of zero-dose children (receiving no vaccines) [4]. Over the past few decades, the substantial increase in population migration has generated two socioeconomically disadvantaged groups: migrant children in urban areas and left-behind children in rural areas in China [5,6]. In previous research, low self-paid vaccination rates were observed in these two growing groups of children [7]. To deliver targeted interventions for promoting the uptake of self-paid vaccines, more attention should be paid to the zero-dose vaccination population in migrant and left-behind families [8].

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the rate and associated factors of zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines and its potential factors among migrant and left-behind children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in urban areas in Zhejiang Province, with a large number of migrant families, and rural areas in Henan Province, with a large number of left-behind families. A total of 1648 children aged 1–6 years and their caregivers were divided into four groups based on their migration status: urban local, migrant, non-left-behind, and left-behind. Left-behind families refer to one or both parents migrating into cities for work, leaving their children in the rural communities with other caregivers (e.g., grandparents) for over six months [7], while non-left-behind families refer to rural local counterparts. Migrant families refer to parents migrating into cities to work together with their children for over six months [9]. Zhejiang University School of Public Health Medicine Ethics Committees approved this study protocol (ZGL202206-6, 1 July 2022).

2.2. Measures

Self-paid vaccines: hemophilus influenza b (Hib), varicella, rotavirus, enterovirus 71 (EV71), and 13-valent pneumonia (PCV 13) vaccine [10].

Knowledge of vaccination: seven items, including convenience, category, efficiency, continuity, time, schedule, and adverse events. This variable was then dichotomized into good (aware of all items) and poor (not aware of at least one item).

Experience of vaccination: nine items, including convenience, reminder, environment, consultation, skills, service quality, process, education, and time. This variable was then dichotomized into satisfied (satisfied with all items) and unsatisfied (not satisfied with at least one item).

Demographic characteristics: the socio-demographic characteristics of the child included age (1–2 years vs. >2 years), sex (boy vs. girl), and birth order (first-born vs. later-born). The socio-demographic characteristics of the caregiver included family role (parents vs. others), age (≤35 years vs. >35 years), sex (male vs. female), education level (elementary school or lower vs. middle school vs. junior college or higher), total household income (less than average vs. more than average), physical health (assessed by 12-Item Short Form Survey [SF-12]), and mental health (assessed by SF-12).

2.3. Data Analysis

The zero-dose prevalence of self-paid vaccines, knowledge and experience of vaccination, socio-demographic characteristics, and reasons for the zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines were described as a number (percentage).

Log-binomial regression models were used to calculate prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for zero-dose vaccination in different types of children, regarding local urban children as a reference. To explore the associated factors of zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines, socio-demographic characteristics were entered in a multivariable logistic regression model, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated to compare the association between the socio-demographic factors and zero-dose vaccination in the total sample and four migration types of children.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and R 3.6.1.

3. Results

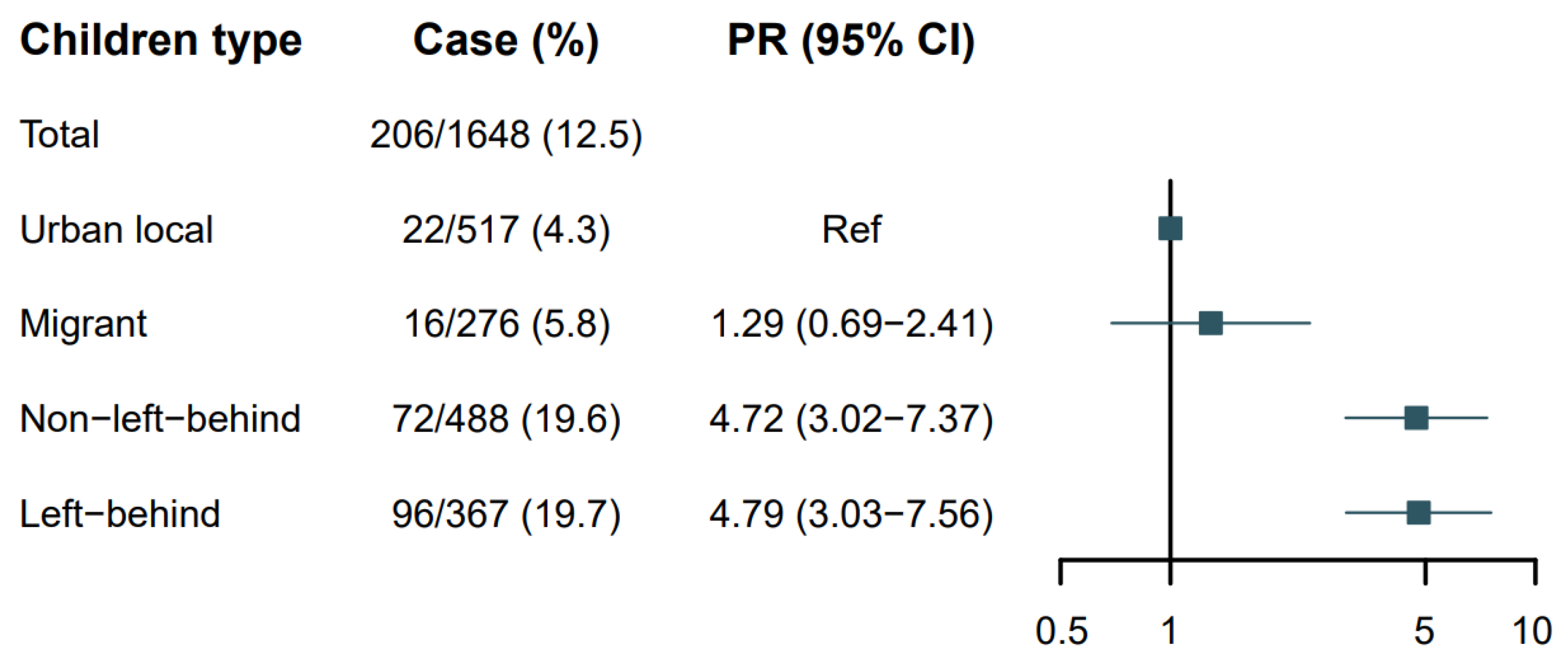

The overall prevalence of zero-dose vaccination was 12.5% (206/1648) in the included families. Specifically, the prevalence was 4.3% (22/517) among urban local children, 5.8% (16/276) among migrant children, 19.7% (96/488) among non-left-behind children, and 19.6% (72/367) among left-behind children. Setting urban local children as the reference, migrant [prevalence ratios (PRs): 1.29, 95% confidence intervals (CIs): 0.69–2.41], non-left-behind (4.72, 3.02–7.37), and left-behind (4.79, 3.03–7.56) children were more likely to be zero-dose vaccinated (Figure 1). The zero-dose prevalence and PRs for single self-paid vaccines are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The zero-dose prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of self-paid vaccines according to children type (n = 1648).

Table 1.

The zero-dose prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of five self-paid vaccines according to children type (n = 1648).

As for the associated factors, children aged 1–2 years [odds ratio (OR): 1.60, 95% CI: 1.14–2.23] and born later (1.55, 1.12–2.14), and caregivers aged >35 years (1.49, 1.03–2.15) and less educated (elementary school or lower: 4.22, 2.39–7.45) were less likely to receive self-paid vaccination. Caregivers other than parents (0.62, 0.41–0.94) and with lower household income (0.67, 0.49–0.90) was more likely to receive self-paid vaccination. However, the above-mentioned associations attenuated to non-significance in specific family types. For example, the higher likelihood of zero-dose vaccination was only observed among caregivers of urban local children with lower educational levels (middle school, 2.88, 1.10–7.54), and no characteristics significantly influenced the zero-dose vaccination in migrant children. For non-left-behind children, caregivers with poor knowledge of immunization (0.57, 0.32–0.99) were more likely to get their children vaccinated with ≥1 self-paid vaccine. For left-behind families, the later-born children experienced higher likelihood of zero-dose immunization (1.91, 1.09–3.36) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The associations between socio-demographic characteristics of children and caregivers, and zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines among the four children types.

Table 3 shows the reasons for zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines. For urban local zero-dose families, the main reasons for zero-dose vaccination were “never heard this vaccine” (40.9%) and “heard of negative information of vaccination” (31.08%). In the other three families, a large proportion of caregivers reported that they “didn’t know where to get a vaccination”, with responses ranging from 82.3% to 93.8%. In addition, nearly half of the caregivers of rural children reported the reasons “the efficacy of self-paid vaccines is concerning”, “having no time to get the children vaccinated”, and “there is no risk of contracting the disease”.

Table 3.

Reasons for the zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines among the four children types.

4. Discussion

The growing number of zero-dose children has been well recognized by global health strategies. For example, the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 [11] and the Gavi Strategy 5.0 [12] set out the goal of “leaving no one behind” [9] and put core focus on reaching zero-dose children and increasing equitable use of vaccines. Although China has made many efforts to promote nationwide vaccination over decades, many children still do not receive any self-paid vaccines. This study not only observed a difference in zero-dose vaccination coverage between urban and rural areas but also found that the rates of zero-dose vaccination of urban migrant children, rural non-left-behind, and left-behind children were higher than those of urban local children. Compared to urban local children, the other three types of children are at a socioeconomic disadvantage, with poorer sanitation and lower utilization of health services [13,14]. Therefore, reducing or eliminating the equity on self-paid vaccination should be focused on migrant children and rural children.

For non-left-behind families, the probability of zero-dose vaccination was higher for families of children aged 1–2 years and caregivers aged >35 years. These findings suggested that self-paid vaccination promotion should be delivered as soon as possible for families with age-eligible children, and younger family members should be encouraged to participate in the decision-making process of self-paid vaccination. However, the knowledge level of immunization was reversely associated with zero-dose vaccination of self-paid vaccines, which may be due to the bias of information sources in rural areas [15]. For left-behind children, those born later were more likely to be unvaccinated than those born first. One possible explanation was that the first-born children gained more attention and support from family members, while those born later had limited access to parental time and supervision [16,17]. Caregivers who were not parents (mainly grandparents) and with lower household income were more likely to vaccinate their children, perhaps suggesting grandparent–grandchild cohesion theory, which refers to the intimate emotional bond between children and their grandparents [18]. It also highlights the need to consider the structure and socioeconomic status of left-behind families when policymakers and vaccinators implement non-NIP vaccination promotion programs. Flexible vaccination promotion programs, including mobile vaccination units or school-based vaccination programs, also have high practical value. Future studies are also needed to explore whether logistic factors, such as distance to healthcare facilities, availability of health professionals, or vaccination costs, impede self-paid vaccine uptake.

The reasons for zero-dose self-paid vaccination among the four children types were also analyzed. The main reasons included “don’t know where to get vaccinated”, “have no time”, “think no risk of contracting the disease”, and “concern about the efficacy”. These findings provided primary workers imperatives for standardizing the vaccination process and alternating vaccination service hours (e.g., off-peak services). Health education, including knowledge of target diseases, the safety and efficacy of each self-paid vaccine, and the local vaccination process, can help promote self-paid vaccination.

This study had some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precluded us from exploring the longitudinal effects of the associated factors. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to offer insights into how associated factors influence zero-dose vaccination over time. Second, this study only focused on self-paid vaccines. Including data on government-provided vaccines would present a more comprehensive picture of vaccine equity, particularly in vulnerable populations. Third, our findings should be generalized with caution because the study participants were from two provinces in China. However, these two provinces are the major labor-importing or labor-exporting provinces in China, and the simple random sampling method was used to select participants. Therefore, serious bias is impossible. Fourth, due to the small sample size, the sample of some categories of variables were too small (e.g., age and birth order of children and caregivers) to further conduct subgroup analyses. Future large studies focusing on those aged 1–2 years and born later are warranted to yield targeted intervention strategies.

5. Conclusions

The rate of zero-dose self-paid vaccination was higher among urban migrant, non-left-behind, and left-behind children in rural areas than among urban local children. The socio-demographic characteristics of children and caregivers (e.g., educational level) were associated with zero-dose self-paid vaccination, and caregivers reported their lack of time, information, and knowledge on self-paid vaccines. Migrant children and rural children should be optimized in the promotion of self-paid vaccination (e.g., targeted health education) to achieve the goal of “leaving no one behind”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and H.D.; methodology, X.X., S.T. and H.D.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z., X.X., H.D., S.C. and S.T.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z., S.C. and X.X.; resources, Y.Z. and X.X.; data curation, Y.Z. and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.X., H.D., S.C. and S.T.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, X.X. and S.T.; project administration, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-034554).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by Zhejiang University School of Public Health Medicine Ethics Committees (protocol code ZGL202206-6).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants and the team members who contributed to this study. The work reported in this publication is part of the research program entitled “Innovation Lab of Vaccine Delivery Research”, hosted at Duke Kunshan University and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-034554). The work is also supported in part by a research grant from the Investigators Studies Research Program of MSD. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the investigators and do not necessarily represent those of MSD.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, W.; Lee, L.A.; Liu, Y.; Scherpbier, R.W.; Wen, N.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, X.; Ning, G.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; et al. Vaccine-preventable disease control in the People’s Republic of China: 1949–2016. Vaccine 2018, 36, 8131–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G. A 60-Year History of Disease Prevention and Control in China; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Ying, X.; Tang, S. The coverage and challenges of increasing uptake of non-National Immunization Program vaccines in China: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Hou, Z.; Fang, H.; Meng, Q. Are providers’ recommendation and knowledge associated with uptake of optional vaccinations among children? A multilevel analysis in three provinces of China. Vaccine 2019, 37, 4133–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X. China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science 2011, 333, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Cui, L. Acculturation and adjustment among rural migrant children in urban China: A longitudinal study. Applied Psychology. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics, Office of the Seventh National Population Census Leading Group of the State Council. Seventh National Census Bulletin (7), Urban and Rural Population and the Foating Population Situation. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202302/t20230206_1902007.html (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Utazi, C.E.; Aheto, J.M.K.; Wigley, A.; Tejedor-Garavito, N.; Bonnie, A.; Nnanatu, C.C.; Wagai, J.; Williams, C.; Setayesh, H.; Tatem, A.J.; et al. Mapping the distribution of zero-dose children to assess the performance of vaccine delivery strategies and their relationships with measles incidence in Nigeria. Vaccine 2023, 41, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Cao, Y.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y.; Long, Q.; Zhang, Z.; An, C.; Xu, X. Immunization coverage, knowledge, satisfaction, and associated factors of non-National Immunization Program vaccines among migrant and left-behind families in China: Evidence from Zhejiang and Henan provinces. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonodi, C.; Farrenkopf, B.A. Defining the Zero Dose Child: A Comparative Analysis of Two Approaches and Their Impact on Assessing the Zero Dose Burden and Vulnerability Profiles across 82 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/immunization/immunization_agenda_2030/en/ (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Gavi the Vaccine Alliance. Gavi Strategy 5.0, 2021–2025. 2020. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/strategy/phase-5-2021-2025 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Ke, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Tang, W. Inequality in health service utilization among migrant and local children: A cross-sectional survey of children aged 0–14 years in Shenzhen, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellmeth, G.; Rose-Clarke, K.; Zhao, C.; Busert, L.K.; Zheng, Y.; Massazza, A.; Sonmez, H.; Eder, B.; Blewitt, A.; Lertgrai, W.; et al. Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 392, 2567–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Tiefengraber, D.; Wiedermann, U. Towards understanding vaccine hesitancy and vaccination refusal in Austria. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Family size and the quality of children. Demography 1981, 18, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, J. Number of siblings and educational attainment. Science 1989, 245, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J. The longitudinal associations among grandparent-grandchild cohesion, cultural beliefs about adversity, and depression in Chinese rural left-behind children. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).