Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction, Analysis, and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Survey Characteristics

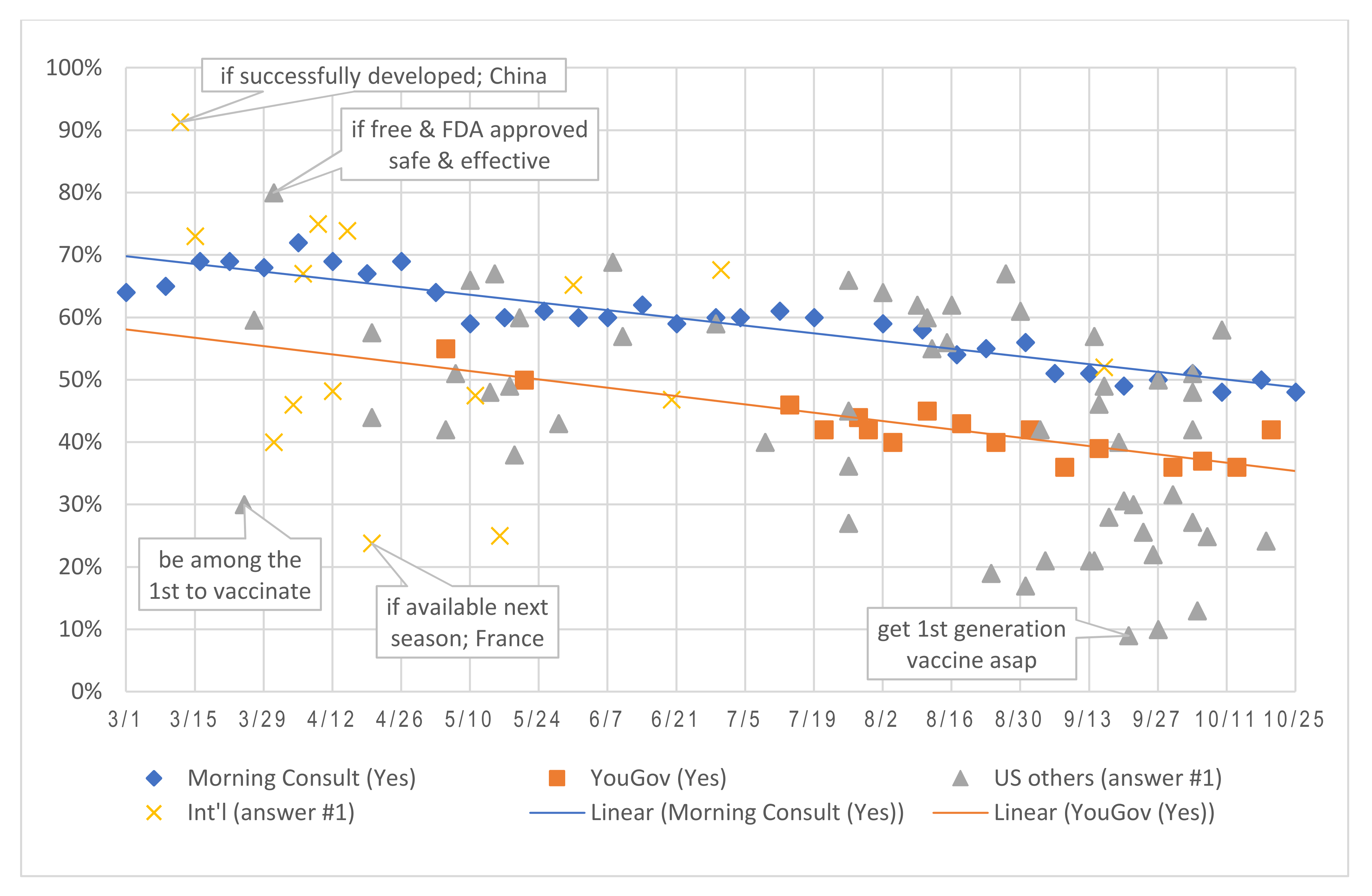

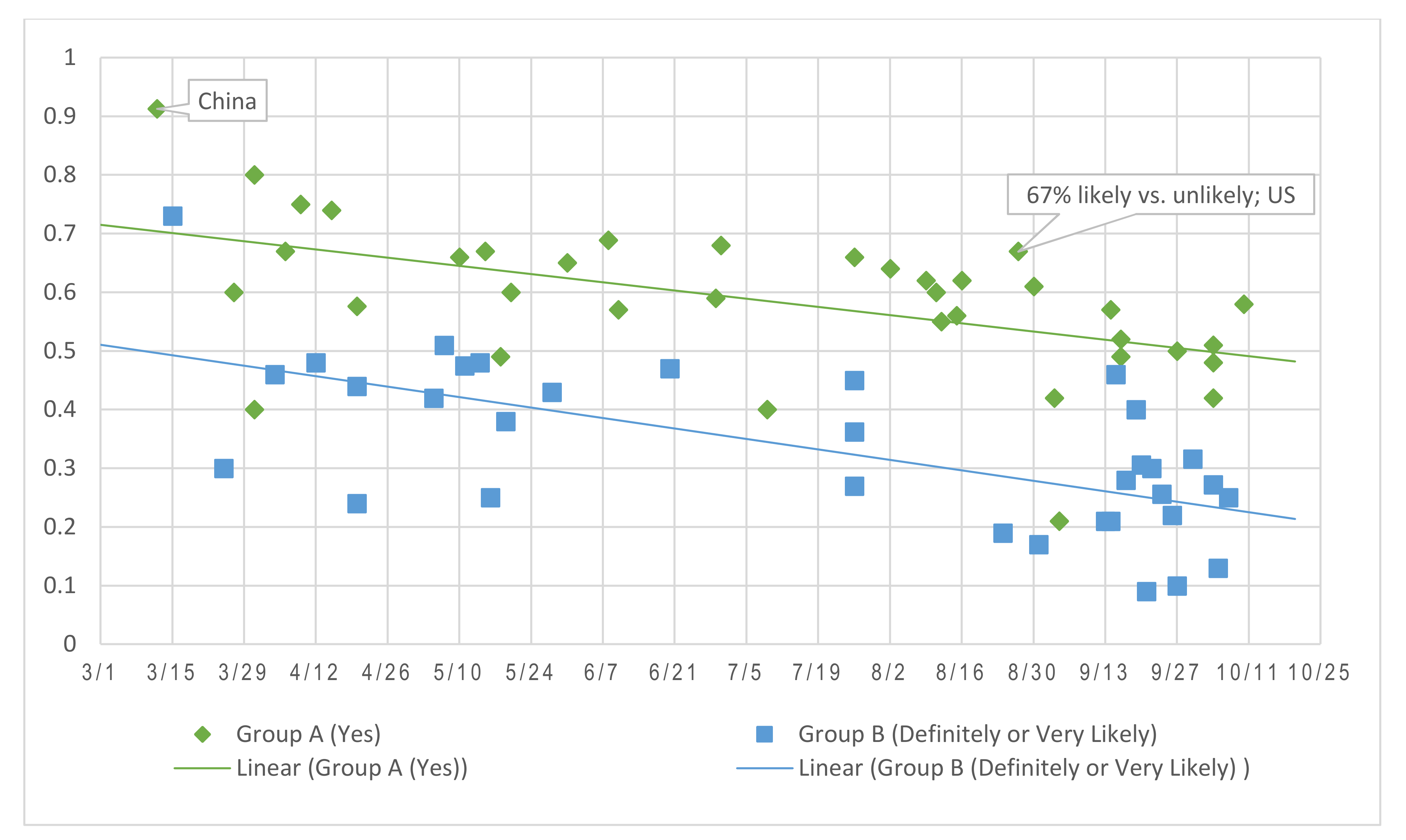

3.2. Trends in Vaccine Acceptance, Hesitancy, and Refusal

3.2.1. Demographics Variables

3.2.2. Vaccine Attributes and Individual Factors

3.3. Assessing the Impact of Survey Design

3.4. Contextual and COVID-19 Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Literature Search Strategy

| Set # | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “coronavirus”[MeSH Terms] OR “coronavirus”[All Fields] OR “coronaviruses”[All Fields] OR “covid 19”[All Fields] OR “SARS-2”[All Fields] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[All Fields] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[Supplementary Concept] OR “ncov”[All Fields] OR “2019 ncov”[All Fields] OR “sars cov 2”[All Fields] OR ((“coronavirus”[All Fields] OR “cov”[All Fields]) AND 2019/11/01:3000[Date—Publication]) | 80,867 |

| 2 | “vaccines”[MeSH Terms] OR “vaccin”[All Fields] OR “vaccination”[MeSH Terms] OR “vaccination”[All Fields] OR “vaccinable”[All Fields] OR “vaccinal”[All Fields] OR “vaccinate”[All Fields] OR “vaccinated”[All Fields] OR “vaccinates”[All Fields] OR “vaccinating”[All Fields] OR “vaccinations”[All Fields] OR “vaccination’s”[All Fields] OR “vaccinator”[All Fields] OR “vaccinators”[All Fields] OR “vaccine s”[All Fields] OR “vaccined”[All Fields] OR “vaccines”[All Fields] OR “vaccine”[All Fields] OR “vaccins”[All Fields] OR “vaccin”[Supplementary Concept] | 394,922 |

| 3 | “surveys and questionnaires”[MeSH Terms] OR “survey”[All Fields] OR “surveys”[All Fields] OR “survey’s”[All Fields] OR “surveyed”[All Fields] OR “surveying”[All Fields] OR (“surveys”[All Fields] AND “questionnaires”[All Fields]) OR “surveys and questionnaires”[All Fields] OR (“questionnair”[All Fields] OR “questionnaire’s”[All Fields] OR “surveys and questionnaires”[MeSH Terms] OR (“surveys”[All Fields] AND “questionnaires”[All Fields]) OR “surveys and questionnaires”[All Fields] OR “questionnaire”[All Fields] OR “questionnaires”[All Fields]) OR “poll”[All Fields] | 1,705,583 |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 298 |

| 5 | Filters: from 2020/1/1 | 216 |

| Set # | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘covid 19’ OR ‘covid 19’/exp OR coronavirus OR coronavirus/exp OR ‘2019 ncov’ OR ‘2019 ncov’/exp OR ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’ OR ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’/exp OR ‘SARS-COV 2’ OR ‘SARS-COV 2′/exp | 86,215 |

| 2 | vaccine OR vaccine/exp OR vaccination OR vaccination/exp OR immunization OR immunization/exp | 603,926 |

| 3 | survey OR survey/exp OR questionnaire OR questionnaire/exp OR poll OR poll/exp | 2,177,885 |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 306 |

| AND [2020–2020]/py | 173 |

| Set # | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | covid-19 OR coronavirus OR 2019-ncov OR sars-cov-2 OR cov-19 | 2162 |

| 2 | vaccine OR vaccines OR vaccination OR immunization OR immunizations | 9407 |

| 3 | survey OR questionnaire OR poll | 709,844 |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 6 |

| Response Percentages | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Dates (# in Series) | Author or Organization [int’l Study] | Sample Size (n) † | Main Question | Answer Choices | Yes, Very Likely | Some-what Likely, Probably | Not Sure, Don’t Know | Some-what Unlikely, Probably Not | No, Not at All Likely, Very Unlikely | Key Findings and Relevant Factors |

| 2/28–3/1 (1 of 33) | Morning Consult [131] | 2020 | If a vaccine that protects from the coronavirus became available, would you get vaccinated or not? | Yes/don’t know/no | 64% | 25% | 11% | More likely to accept COVID vaccine: male, 18–29, Liberal, post-grad, higher income, work in government | ||

| March | Wang et al. [29] [China] | 2058 | If a COVID-19 vaccine is successfully developed and approved for listing in the future, would you accept vaccination? | Yes/no | 91% | 9% | 80% consider doctors’ recommendation, 60% said price important; 52% would get as soon as possible (ASAP) and 48% wait ‘til confirmed safe; 64% no preference for domestic vs. imported vaccine. More likely: male, married, high risk, pandemic large impact, convenient | |||

| March | Abdelhafiz et al. [17] [Egypt] | 559 † | If there is an available vaccine for the virus, I am willing to get it. | Strongly agree/ agree/neither agree or isagree/disagree/ strongly disagree | 73% | 15.6% | 4% | 2% | 5% | Younger group have higher COVID knowledge, male-female similar; 86% view COVID dangerous, 16.8% think media coverage exaggerated; 26.8% believe COVID designed as biological weapon; overall positive toward preventative measures |

| 3/24–3/25 | Morning Consult, NBC LX [132] | 2200 | If a vaccine for coronavirus—aka COVID-19—became available, how quickly would you get vaccinated, if you were to get vaccinated at all? | Among the first/ in the middle/ I don’t know/ among the last/ I would not get vaccinated | 30% | 34% | 15% | 11 | 9% | Asked if vaccine should be required, free, development accelerated skipping clinical trials, benefits outweigh risks. 74% likely to get if passes trials; 30% “be in a rush” to get FDA-approved vaccine. 66% believe vaccine more effective than social distancing to control spread |

| 3/17–3/27 | Romer et al. [86] | 1050 | If there were a vaccine that protected you from getting the coronavirus, how likely, if at all, would you be to decide to be vaccinated? | Very likely/likely/ not likely/not at all likely | 60% | 14.5% (3 + 4) | Assessed conspiracy theory impact: hesitancy increase predicted by earlier beliefs (“pharma created coronavirus to increase sales”, “MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine can cause neurological disorders”). Conservative and social media use positively related to conspiracy thinking | |||

| 2/26–3/31 | Wang et al. [7] [Hong Kong] | 806 † | Asked whether or not they intended to accept COVID vaccination when it is available. | Intend to accept/ not intend to accept (undecided) | 40% | 60% | Nurses. More likely: in public sector, 30–39, w/chronic condition, infection likelihood. Refusal reasons: efficacy/safety concerns, believed unnecessary, no time. Past flu vaccination strong predictor and lessened high hesitancy. Increased flu shot intent b/c COVID. | |||

| 3/24–3/31 | Thunstrom et al. [48] | 3133 | Would anyone in your family get the coronavirus vaccine (conditions: FDA approved, 60% effective, available today, free)? | Would/would not | 80% | 20% | Compared scenarios. Concerns: vaccine newness, side effects/efficacy. Less likely: female, believe in God, not had flu shots. Inconsistent risk messages (White House vs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)) deterrence. Those refused also won’t vaccinate their child. | |||

| 3/28–4/4 | Ali et al. [16] [Bahrain] | 5677 † | Suppose that a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine was available today. How likely are you to get yourself vaccinated? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ neutral/ somewhat unlikely/ very unlikely | 46% | 26.20% | 18% | 6.60% | 3% | Posted on social media. Most knowledgeable of COVID symptoms and preventive measures. More likely: younger (only 7.5% 18–34 year unlikely vs. 14.6% 35+), male, work/study in healthcare (51.7% very likely vs. 44.2% public)—also higher perceived infection risk. Main COVID info sources: social media and World Health Organization (WHO). |

| 3/25–4/6 | Harapan et al. [63] [Indonesia] | 1068 | Whether they would be vaccinated with a new COVID-19 vaccine for each scenario (50% or 95% effective). | Yes/no | 67% (@50% efficacy) | 33% | Question premise: tested clinically, free and optional, 5% chance side effect. Compared scenarios: 93% accept @95% efficacy. More likely @95%: healthcare workers (HCW) (aOR: 2.01) and higher perceived risk (aOR: 2.21); retired less likely. If @50%: HCW (aOR: 1.57). | |||

| 3/26–4/9 | Dror et al. [62] [Israel] | 1941 | Would you vaccine yourself for COVID-19? | Yes/no | 75% | 25% | Compared w/HCW. 70% public and Drs had safety concern. More likely: male, higher perceived risk, doctors (78%), lost job due to COVID (96%). 70% public likely to vaccinate their child, vs. 60% Drs and 55% nurses. | |||

| 4/3–4/12 | Wong et al. [34] [Malaysia] | 1159 | If a vaccine against COVID-19 infection is available in the market, would you take it? | Definitely/ probably/possibly/probably not/ definitely not | 48% | 29.80% | 16% | 3.30% | 2.40% | Health Belief Model: benefit belief (OR: 2.51) and feel less worried having vaccine (OR: 2.19). High perceived infection risk and barriers (cost, if halal, inadequate info, safety/efficacy concerns). Avg willingness to pay US$30.66; 74.3% will wait to get vaccinated. |

| 4/13–4/14 | Earnshaw et al. [84] | 845 | When a vaccine becomes available for the coronavirus, how likely are you to get it? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/ unlikely/ not at all likely | 85.8% (1 + 2 + 3) | 14% (4 + 5) | Less likely: women, less edu, believed conspiracies (3.9 X less). 33% w/conspiracy beliefs: younger, Black and minorities, college edu, less COVID knowledge and policy support, medical mistrust, use social media. Drs are most trusted info source (90%). | |||

| 4/2–4/15 | Neumann-Bohme et al. [22] [7 European countries] | 7664 | If available, would you be willing to get vaccinated? (not exact wording) | Yes/unsure/no | 74% | 19% | 7% | 7 nations, willingness varied: France 62%—Denmark 80%; opposition 10% in Germany and France; largest unsure: France 28%. More likely: 55+, male; women reject 2X men. 55% concerned about side effects. | ||

| 2/26–4/20 | Detoc et al. [18] [France] | 2512 † | If a vaccine against the new coronavirus was available for next season, would you get vaccinated? | Yes, certainly/ yes, possibly/I don’t know/No, possibly/ Definitely no | 24% | 53.8% | 12.1% | 6.4% | 3.9% | More likely: men, older, fear COVID, perceived risk, HCW (81.5% vs. 73.7%). 74.7% fear COVID, 65.2% self-considered at risk. 47.6% would participate in clinical trials: older, men, HCW, higher perceived risk |

| 4/16–4/20 | Fisher et al. [1] | 1000 | When a vaccine for the coronavirus becomes available, will you get vaccinated? | Yes/not sure/no | 57.6% | 31.6% | 10.8% | Less likely: younger, female, Black/Hispanic, lower income/edu, larger household, rural, not had flu shot. Qualitative inquiry of reasons. Hesitant: specific vaccine concerns, antivaccine attitudes, not trusting entitles involved in vaccine dissemination. | ||

| 4/18–4/20(1st of 2) | The Harris Poll [133] | 2029 | How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ not very likely/ not at all likely | 44% | 29% | 16% | 12% | (Part of longitudinal study since 3/14 on other topics) 57% would likely get flu shot; 73% for COVID: 86% in Michigan, 72% in NY. Parent vs. non-parent similar likelihood (75% and 72%) | |

| 4/7–5/4 | Ward et al. [10] [France] | 5018 | whether they would agree to get vaccinated if a vaccine against the COVID-19 was available | Certainly/ probably/ probably not/ certainly not | 76% (1 + 2) | 16.1% | 8% | Asked partisan preferences, COVID concerns and diagnosis. More likely: Far Right parties, females, <35 year, high school edu. Refusal reasons: against vaccination in general, too rushed, thought useless. | ||

| 4/29–5/5 (1 of 2) | Pew Research Center [30] | 10,957 | If a vaccine were available today, I definitely/ probably ____ get it | Definitely/ probably/ probably not/ definitely not (no response) | 42% | 30% | 16% | 11% | More likely: male, Boomer+, postgrad, Democrat, Catholic. 74% White and Hispanic, 91% Asian, 54% Black; 74% Dem vs. 54% Rep said clinical trials important. 59% said benefits of allowing more people access outweigh risks. | |

| 5/4–5/5 (1 of 17) | YouGov, Yahoo News [40] | 1573 | If and when a coronavirus vaccine becomes available, will you get vaccinated? | Yes/not sure/no | 55% | 26% | 19% | When would be available: 51% believed in 2021, 24% in 2020. More likely: 18–29, Hispanic (62%), Democrat, suburb, higher income. Male 56% vs. female 54%. | ||

| 5/6–5/7 (1 of 2) | ABC News, Ipsos [66] | 532 | If a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine is developed, how likely would you be to get vaccinated? | Very/somewhat/ not very/not at all (no answer) | 51% | 24% | 14% | 11% | 77% concerned self or someone they know will be infected (66% in March). 64% view opening now not worth it b/c would lead to more deaths | |

| 5/10–5/16 (1 of 3) | CNN/SSRS [134] | 1112 | If a vaccine to prevent coronavirus infection was widely available at a low cost, would you, personally, try to get that vaccine, or not? | Yes/no/ no opinion | 66% | 33% | More likely: 65+, Trump disapproving, college grad, Democrat. 36% feel more comfortable if vaccine existed; 41% more comfortable returning to regular routine. | |||

| 5/4–5/11 | Freeman et al. [85] and compliance with government guidelines in England [England] | 2501 | Take a COVID-19 vaccine if offered? | Definitely/ probably/possibly/probably not/ definitely not | 47.5% | 22.1% | 18.4% | 7.3% | 4.8% | 50% endorse conspiracy beliefs. Higher conspiracy thinking: less adherence to all gov guidelines, less willingness to take tests or vaccine, more likely to share opinions, also connect to other mistrust. |

| May | Reiter et al. [2] | 2006 † | How willing would you be to get the COVID-19 vaccine if it was free or covered by health insurance? | Definitely not willing/probably not willing/ not sure/ probably willing/ definitely willing | 48% | 21% | 17% | 5% | 9% | Less likely: Black, low income, uninsured, conservative. 35% would pay $50+. Provider recommendation, perceived risk and severity, vaccine effectiveness (or harms) correlated w/acceptability |

| May | Malik et al. [9] | 672 | If a vaccine becomes available and is recommended for me, I would get it. | Agree/strongly agree/neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 67% | 33% | Compared US regions/states, between flu and COVID vaccine acceptance. Region 2-NY lowest (thought epicenter). Highest rates: ND, SD, MN, MT, WY, UT, CO. Less likely for both vaccines: Blacks, lower income/edu | |||

| May | Graffigna et al. [8] [Italy] | 1004 | Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 whenever the vaccine is available. | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/unlikely/not at all likely | 25% | 33% | 26% | 7% | 8% | Path Model: health engagement positively related to intention, mediated by general vaccine attitude, perceived severity and susceptibility; invariant across gender, parallel w/other nations (France, US, Poland) |

| 5/14–5/18 | The Associated Press, Univ of Chicago, AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research [49] | 1056 | If a vaccine against the coronavirus becomes available, do you plan to get vaccinated? | Yes/not sure/no | 49% | 31% | 20% | Top concern: side effect. 55% of those worried self/family get infected would vaccinate. 61% believe it will be available in 2021. Acceptance reasons: protect self and family, feel safe around others, best way to avoid getting seriously ill. | ||

| 5/13–5/19 | Reuters, IPSOS [135] | 4428 | How interested would you be in getting a coronavirus/COVID-19 vaccine, if at all? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ unsure/ not very likely/ not at all likely | 38% | 27% | 11% | 10% | 14% | 48% worried vaccine coming out quickly, 42% concerned risks; most be more interested if there was large scientific study to confirm safety. Refusal reasons: newness, risks outweighing benefits. More interest if developed in US vs. Europe or China |

| 5/17–5/20 (1 of 2) | Beacon Research, Shaw and Co Research, Fox News [136] | 1207 | Do you plan to get a vaccine shot against coronavirus when a vaccine becomes available, or not? | Yes/don’t know/no | 60% | 16% | 23% | 61% “very” concerned about spread of coronavirus in US (also compared swine flu vaccine opinions in 2009). | ||

| 5/23–5/28 | Washington Post, ABC News [67] | 1001 | If a vaccine that protected you from the coronavirus was available for free to everyone who wanted it, would you get it? | Definitely/ probably/ probably not/ definitely not | 43% | 28% | 12% | 15% | Refusal reasons: lack of trust, thought unnecessary. 57% believed more important to control pandemic even if it hurts the economy | |

| 3/26–5/31 | Goldman et al. [19] [Canada, Israel, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, US] | 1541 † | There is no vaccine/ immunization currently available for Coronavirus (COVID-19). If a vaccine was available today, would you give it to your child? | Yes/no | 65% | 33% | Asked caregiver (mostly parents) willingness to vaccinate their child; w/follow-up open questions. More likely: older age of children and caregiver, up-to-date on vaccination, no chronic illness, father surveyed, more concerned about child than self having COVID. Intent: protect child; common refusal b/c vaccine novelty | |||

| 5/28–6/8 | Callaghan et al. [42] | 5009 | Scientists around the world are working on developing a vaccine to protect individuals against the coronavirus. If a vaccine is developed, would you pursue getting vaccinated for the coronavirus? | Yes/no | 68.9% | 31.1% | Compared and hypothesized hesitancy reasons across subgroups. Blacks 40% more likely to refuse b/c lack of trust in safety, efficacy, and financial resources. Less likely: women, conservatives, those see vaccines unimportant/ineffective, Trump voters, religious. Those been tested for COVID 68% less likely to refuse vaccination. | |||

| 5/29–6/10 | Tufts Univ Research Group on Equity in Health, Wealth and Civic Engagement [33] | 1267 | If a vaccine were available today, would you be willing to get it? (not exact wording) | Yes/don’t know/no | 57% | 24% | 18% | Examined hesitation in equity context. More likely: Whites, Hispanics, Democrats, more formal edu, higher income. Further widened “the gap in health outcomes” | ||

| 6/16–6/20 | Lazarus et al. [21] [19 countries] | 13,426 | If a COVID-19 vaccine is proven safe and effective and is available to me, I will take it. | Completely agree/ somewhat agree/ neutral/ somewhat disagree/ completely disagree | 47% | 24.7% | 6.1% | 8% | Compare globally. Highest: China 88.6%, Brazil 85.4%, S Africa 81.6% (US 75%); lowest—Russia 54.9%. Highest refusal: Russia 27.3%. 61.4% would follow employer recommendations. More likely: trust gov, higher income/edu, older (18–24 least), women slightly more, higher national case and mortality rates. Younger more likely to accept if employer suggest. | |

| 6/19–6/29(1 of 2) | YouGov, Univ of Texas [91] | 1200 | If a vaccine to prevent coronavirus infection were widely available at a low cost, would you try to get that vaccine, or not? | Yes/no opinion/no | 59% | 20% | 21% | Texas. 75% believe gov should require parents to have their children vaccinated against infectious diseases, 14% disagreed | ||

| 3/26–6/30 | Goldman et al. [20] [Canada, Israel, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, US] | 2557 † | Would you vaccinate your child against COVID-19 if a vaccine existed today? | Yes/no | 68% | 32% | 43% willing to accept less strict standards of development and approval; More likely to vaccinate their child: if father surveyed (compared to mother), child have followed recommended vaccination schedule, concerned about having COVID-19 | |||

| 7/9 | Kreps et al. [53] | 1971 | How likely to receive a (scenario 1) vaccine with 50% efficacy, a 1-year protection duration, was approved under an FDA EUA, and developed in China? | (model estimated willingness) | 40% | Compare scenarios. More likely: increased efficacy and protection duration, decreased in adverse effect; had regular flu shots, favorable attitudes toward pharma. Less willing: female, Black, personal contact w/someone tested positive, believe pandemic would worsen; if FDA EUA or non-US-made; if endorsed by Trump (vs. CDC/WHO). | ||||

| 7/10–7/26 (1 of 2) | COVID-19 Consortium for Understanding the Public’s Policy Preferences Across States, PureSpectrum [24] | 19,058 | If a vaccine against COVID-19 was available to you, how likely would you be to get vaccinated? | Extremely likely/somewhat likely/neither likely nor unlikely/somewhat likely/extremely unlikely | 45% | 21% | 15% | 6% | 12% | Compare 50 states @30–50–70–90% effectiveness. Top factors: safety, effectiveness, side effects, protect self/family, Dr. recommend. 66% would vaccinate their children. Associated w/mask-wearing. >60%: AL, AR, LA, MS, MO, OH, OK, SD, WV, WY. 70%+: AZ, CA, Iowa, MD, MA, MN, ND, NY, RI, UT, WA, DC. More likely: Asian, male, 65+, Democrat |

| 7/20–7/26 (1 of 6) | Gallup [40] | 7632 | If an FDA-approved vaccine to prevent coronavirus/ COVID-19 was available right now at no cost, would you agree to be vaccinated? | Yes/no | 66% | 34% | Compared ethnicities “whites” and “non-whites”: 67% vs. 59%. 83% Democrats vs. 46% Republicans; men (67%) and women (65%) relatively equally likely. Least likely: middle age (vs. 76% 18–29 and 70% senior) | |||

| 7/24–7/26 | Lending Tree, Value Penguin [54] | 1010 | Once the coronavirus vaccine is available to the public, do you plan to get vaccinated? | Yes/only if covered by insurance/ depends on circumstances/definitely not (I don’t know) | 36.2% | 17.1% (if with insurance) | 25.9% (depends) | 13.9% | 42% would wait at least weeks before getting vaccinated. 51% believe public schools should require; 45% parents would definitely vaccinate their child. ~40% more likely to get flu shot b/c of COVID | |

| 7/24–7/26 | Politico, Morning Consult [57] | 1997 | If the US were to develop a vaccine for the coronavirus that was available to Americans, how quickly would you get vaccinated, if you were to get vaccinated at all? | Among the first/in the middle/ I don’t know/ among the last/ I would not get vaccinated | 27% | 31% | 11% | 14% | 17% | 23% would decline if China-made vs. 17% if US-made, especially among Trump supporters. 64% believe US should prioritize fully testing even if delaying availability and continued COVID spread. 44% trust Biden more to oversee development (vs. 33% Trump) |

| 7/24–7/27 | Axios, Ipsos-Knowledge Panel [137] | 1076 | How much of a risk to your health and well-being do you think the following activities are right now—taking the 1st generation COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it’s available? | No risk/ small risk/ moderate risk/ large risk | 8% | 29% | 43% | 19% | 63% wear mask at all time, 24% sometimes. 69% thought participating in vaccine trial moderate or large risk, 71% thought sending child to school in fall risky. (Many questions on how things/life have changed, social distancing, work/business closing, access to food and healthcare, trust in public figures and institutions/gov.) | |

| 8/3–8/11 (1 of 2) | NPR and PBS NewsHour, The Marist Poll [138] | 1261 | If a vaccine for coronavirus is made available to you, will you choose to be vaccinated or not? | Yes/not sure/no | 60% | 5% | 35% | More likely: Democrat, college degree, 18–29 and 60+; similar percentages compared to 2009 H1N1 vaccine willingness | ||

| 8/9–8/12 (2 of 2) | Beacon Research, Shaw and Co Research, Fox News [139] | 1000 | Do you plan to get a vaccine shot against coronavirus when a vaccine becomes available, or not? | Yes/don’t know/no | 55% | 20% | 26% | Declined willingness from May to August; higher rates compared to earlier swine flu vaccination opinions | ||

| 8/12–8/15 (2 of 3) | CNN/SSRS [140] | 1108 | If a vaccine to prevent coronavirus infection were widely available at a low cost, would you, personally, try to get that vaccine, or not? | Yes/no | 56% | 40% | 40% thought worst of COVID is behind us, 55% though yet to come. 68% felt the way US respond to COVID embarrassed (other choice “proud” 28%). Willingness decreased since May; 62% confident that ongoing trials properly balancing safety and speed | |||

| 8/21–8/24 (1 of 5) | Ipsos/Axois [45] | 1084 | How likely, if at all, are you to get the first generation COVID-19 vaccine, as soon as it’s available? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ not very likely/ not at al likely (no answer) | 19% | 29% | 22% | 29% | 76% social distanced (staying home avoided others) the past week; 68% and 22% wear mask all the time or sometimes; 54% and 37% keep 6-ft from people all the time or sometimes | |

| 8/7–8/26 (2 of 2) | COVID-19 Consortium for Understanding Public’s Policy Preferences Across States, Pure Spectrum [37] | 21,196 | If a vaccine against COVID-19 was available to you, how likely would you be to get vaccinated? | Extremely likely/ somewhat likely/ neither likely nor unlikely/ somewhat likely/ extremely unlikely | 59% (1 + 2) | Trust were lower than in April for every institution/figure (Biden, Trump, CDC, Fauci, News media, social media, state gov, police, etc); trust scientists/ researchers much more than president. 73% Democrats who trust Trump and 84% of Republicans who trust Biden would vaccinate their children. | ||||

| 8/25–8/27 (1 of 2) | STAT/The Harris Poll [75] | 2067 | How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available? | Likely/unlikely | 67% | 33% | 82% Democrats worry vaccine approval more driven by politics than science (vs. 72% Republicans). 46% trust president or WH for accurate COVID info; 68% confident FDA will only endorse a vaccine that is safe | |||

| 8/28–9/3 | Kaiser Family Foundation [141] | 1199 | If a coronavirus vaccine was approved by the U.S. FDA before the presidential election in November and was available for free to everyone who wanted it, do you think you would want to get vaccinated, or not? | Yes/don’t know/no | 42% | 4% | 54% | 62% very/somewhat worried FDA will rush to approve without making sure it’s safe and effective due to political pressure from Trump administration; 81% do not think vaccine will be widely available before election | ||

| 9/2–9/4 | YouGov, CBS News [68] | 2493 | If a coronavirus vaccine became available this year, at no cost to you, would you…? | Get one as soon as possible/consider one/never get one | 21% | 58% | 21% | 75% think president (whoever) should publicly take vaccine to show it is safe; White Democrats 2x more likely than Black. 65% believe vaccine announced this year would be rushed or not had enough testing | ||

| 9/8–9/13 (2 of 2) | Pew Research Center [47] | 10,093 | Asked if they would get a COVID 19 vaccine if it were available today. | Definitely/ probably/probably not/ definitely not | 21% | 30% | 25% | 24% | 72% Asian, 56% Hispanic, 52% White, 32% Black; 44% Rep vs. 58% Dem (72% in May; “definitely” dropped 42% to 21%). 76% concern about side effects—major reason; 77% thought likely it will be approved before fully known safe and effective; 78% concern moving too fast vs. 20% too slow. | |

| 9/11–9/14 | Univ of Chicago School of Public Policy, AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research [142] | 1053 | If a vaccine against the coronavirus becomes available, do you plan to get vaccinated? | Yes/no | 57% | 41% | 58% said US should keep any vaccine it develops for US first vs. 39% believe should make available to others. 52% would get if US-made; 46% would take non-US-developed. 75% Democrat (vs. 39% Republican) thought WHO should have major role in vaccine development | |||

| 9/11–9/14 (1 of 6) | Suffolk Univ, USA Today [23] | 500 | When a federally approved COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you… | Take it as soon as you can/ wait awhile until others have taken it/undecided/ not take it | 21% | 51% (wait) | 4% | 24% | North Carolina. 48.8% would vaccinate If mandated by federal gov (42.2% would not, 8.6% undecided) | |

| Sep-tember | Brigham Young Univ. [5] | 316 | How do you feel about the following statement: I am likely to be vaccinated when a vaccine for COVID-19 becomes available. | Strongly agree/ agree/ neither agree or disagree/disagree/strongly disagree | 46% | 22% | 16% | 7.00% | 9% | Compared scenarios: available timing, @50–75–99% effectiveness, frequency needed. 66% would get if available in 30 days, 74.38% if 6 months; 6–12 months testing be more comfortable. 45.5% concern over safety; more felt comfortable if US-made than other locations. Income/edu and insurance satisfaction positively correlated with intent |

| 9/11–9/16 | Grech et al. [55] [Malta] | 1002 | Based on this info (describe 3-phase development for efficacy and safety). The COVID vaccine that will arrive in Malta will have gone through these Phases and will be approved and licensed, how likely are you to take the COVID-19 vaccine? | Likely/ undecided/unlikely | 52% | 22% | 26% | Surveyed HCWs. More likely: male (64% vs. 45% female), oldest group, doctors. Hesitancy for influenza vaccine: safety, perceived low disease risk, low priority, access, general anti-vaccine | ||

| 9/11–9/16 (2 of 2) | NPR and PBS NewsHour, The Marist Poll [143] | 1152 | If a vaccine for the coronavirus is made available to you, will you choose to be vaccinated or not? | Yes/unsure/no | 49% | 7% | 44% | Declined confidence (60% in August); 13% drop in Independents and 10% Republicans. More likely: Democrat, higher income, college grad, White, over 74, suburban area. 52% were likely to get H1N1 vaccine in 2009. | ||

| 9/14–9/17 | Selzer and Co, DesMoines Register [74] | 803 | When a federally approved vaccine is available, will you take it as soon as you can, wait awhile until others have taken it, or not take the vaccine? | As soon as possible/ wait until others have taken it/ not sure/ not take it | 28% | 45% (wait) | 6% | 21% | Iowa. 45% plan to wait until others have taken it. 6% Democrats won’t take vs. 28% Republicans. Quote from respondent: “I’m 76 years old. I sure don’t want to get this virus. I’m figuring it’s going to be OK. It may not be the best vaccine, but I think it’ll be good.” | |

| 9/18–9/19 (2 of 2) | ABC News, Ipsos [73,144] | 528 | If a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine is developed, how likely would you be to get vaccinated? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/unlikely/not at all likely | 40% | 24% | 19% | 17% | Majority have confidence in Fauci, CDC, WHO, FDA, HHS to confirm safe and effective; 41% confident in Biden and 27% in Trump, 62% in Fauci. | |

| 9/18–9/22 | Ipsos/Newsy [64] | 2010 | Once a COVID-19 vaccine has been developed, if it were approved for use by the FDA, how interested would you be in getting the vaccine? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/unlikely/not at all likely | 30% | 26% | 14% | 20% | 55% say pandemic made them more likely to support increased federal funding for vaccine development and testing, 48% more likely to support Medicare for all (21% less likely) | |

| 9/24–9/26 (2 of 2) | The Harris Poll [51] | 1971 | How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/unlikely/ not at all likely | 22% | 31% | 25% | 21% | 58% would vaccinate kids ASAP. 61% say should only made available abroad once US orders delivered. 42% confident gov approval not motivated by politics; 79% concerned over safety. 33% confident FDA will only approve if safe; 46% say US is prepared to deliver; 47% would use foreign-made. 45% will get flu shot | |

| 9/14–9/27 (6 of 6) | Gallup [12,40] | 2730 | If an FDA-approved vaccine to prevent coronavirus/ COVID-19 was available right now at no cost, would you agree to be vaccinated? | Yes/no | 50% | 50% | 53% Democrats vs. 47% Republicans; 56% men and 44% women; 62% ages 18–34, 44% ages 35–54. Overall observed decline from last survey in August (series started in July) | |||

| 9/25–10/4 (2 of 2) | YouGov, Univ of Texas [26] | 1200 | If a vaccine to prevent coronavirus infection were widely available at a low cost, would you try to get that vaccine, or not? | Yes/no opinion/no | 42% | 21% | 36% | Texas. 41% believe COVID vaccine will be made available before proven safe; decline in vaccine willingness since June survey | ||

| 9/30–10/4 | Goucher College [43,145] | 1002 | If an FDA-approved vaccine to prevent coronavirus was available right now at no cost, would you agree to be vaccinated? | Yes/don’t know/no | 48% | 2% | 49% | Maryland. 69% very or somewhat concerned about self/family contracting COVID. 40% though worst is yet to com. 23% thought reopened too quickly and 58% thought about right. Black more likely to distrust a potential vaccine. | ||

| 10/1–10/4 (3 of 3) | CNN/SSRS [65] | 1205 | If a vaccine to prevent coronavirus infection were widely available at a low cost, would you, personally, try to get that vaccine, or not? | Yes/no | 51% | 45% | Willingness declined since July; shift in willingness for Democrats but Republicans/Trump supporters have remained consistent at 41%. 61% say somewhat-very confident that ongoing trials properly balancing speed and safety. | |||

| 10/1–10/5 (5 of 5) | Ipsos/Axois [72] | 1004 | How likely, if at all, are you to get the first generation COVID-19 vaccine, as soon as it’s available? | Very likely/ somewhat likely/ likely/unlikely/ not at all likely | 13% | 25% | 31% | 31% | 30% likely to get 1st gen ASAP, 55% if it has been on the market for months, 65% if been proven safe/effective by public health officials; 18% likely to get if released before election. 26% would get 1st G if they were paid $100 incentive,33% if paid $500, 45% if paid $1000 (54% not likely). | |

| 9/24–10/7 | YouGov, St. Louis Univ [146] | 931 | If the following FDA approved vaccines were available today for free, you would get it? | Definitely/ probably/ probably not/ definitely not | 25% | 26% | 24% | 26% | Missouri. Higher trust in CDC, Missouri Department of Health and local public health departments vs. FDA; more trust in FDA in Democrats (82% vs. 66%). Democratic 15% more likely to get the vaccine. | |

| 10/7–10/10 (2 of 2) | STAT/The Harris Poll [147] | 2050 | How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available? | Likely/unlikely | 58% | 48% | Declined from 69% in August. 59% Whites and 43% Blacks. 40% more likely to get vaccine once Trump tested positive for COVID, 41% said their opinions had not changed | |||

| 10/16–10/18 (33 of 33) | Morning Consult [31] | 2200 | If a vaccine that protects from the coronavirus became available, would you get vaccinated or not? | Yes/don’t know/no | 50% | 25% | 25% | 55% (64% Blacks) very and 28% somewhat concerned about coronavirus; 56% very and 26% somewhat believed mask effective in preventing spread (older age stronger belief). 26% had family/friend tested positive; 15% know someone personally died from COVID | ||

| 10/15–10/19 (6 of 6) | Suffolk Univ, USA Today [82] | 500 | When a federally approved COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you… | Take it as soon as you can/wait awhile until others have taken it/undecided/ not take it (refuse to answer) | 24.2% | 45.5% (wait) | 7.8% | 22.2% | Pennsylvania. 45.6% get most news from TV, 10.6% newspaper, 7.4% social media, 24.2% online news. (all others were political/election questions) | |

| 10/18–10/20 (17 of 17) | YouGov, The Economist[28] | 1500 | If and when a coronavirus vaccine becomes available, will you get vaccinated? | Yes/not sure/no | 42% | 32% | 26% | Willingness increased from last week’s 36%. 24% Black and 44% Hispanic, 36% female and 48% male; income: 37% for <50 k vs. 51% 100 k+; 48% Dem vs. 34% Rep. More likely: male, college grad, 65+, higher income, West, liberal. 40% believe available by summer 2021; 40% very and 35% somewhat concerned about safety of fast-tracked (declined from last survey). | ||

References

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, P.; Pennell, M.; Katz, M. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, A.M.; Markel, H. The History Of Vaccines And Immunization: Familiar Patterns, New Challenges. Health Aff. 2005, 24, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Orgnization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pogue, K.; Jensen, J.L.; Stancil, C.K.; Ferguson, D.G.; Hughes, S.J.; Mello, E.J.; Burgess, R.; Berges, B.K.; Quaye, A.; Poole, B.D. Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. Vaccines 2020, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, K.; Goldstein, S. Giving Vaccines a Shot? American Enterprise Institute (AEI): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Ho, K.F.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, S.Y.S. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7049–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Palamenghi, L.; Boccia, S.; Barello, S. Relationship between Citizens’ Health Engagement and Intention to Take the COVID-19 Vaccine in Italy: A Mediation Analysis. Vaccines 2020, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinical Med. 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.K.; Alleaume, C.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Launay, O.; Raude, J.; Verger, P.; Beck, F.; et al. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, G. 48% of U.S Adults Now Say They’d Get a COVID-19 Vaccine, a New Low; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, L. Americans’ Readiness to Get COVID-19 Vaccine Falls to 50%. Gallup, 12 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Axios. Axios-Ipsos Poll: Americans won’t Take Trump’s Word on Vaccine. Axios, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informedguidance to conduct rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemol. 2020, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, K.F.; Whitebridge, S.; Jamal, M.H.; Alsafy, M.; Atkin, S.L. Perceptions, Knowledge, and Behaviors Related to COVID-19 Among Social Media Users: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhafiz, A.S.; Mohammed, Z.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Ziady, H.H.; Alorabi, M.; Ayyad, M.; Sultan, E.A. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Attitude of Egyptians Towards the Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). J. Community Health 2020, 45, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Frappe, P.; Tardy, B.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7002–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, R.D.; Yan, T.D.; Seiler, M.; Parra Cotanda, C.; Brown, J.C.; Klein, E.J.; Hoeffe, J.; Gelernter, R.; Hall, J.E.; Davis, A.L.; et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: Cross sectional survey. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7668–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.D.; Marneni, S.R.; Seiler, M.; Brown, J.C.; Klein, E.J.; Cotanda, C.P.; Gelernter, R.; Yan, T.D.; Hoeffe, J.; Davis, A.L.; et al. Caregivers’ Willingness to Accept Expedited Vaccine Research During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 2124–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk University/USA Today Poll—North Carolina; Suffolk University: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Perlis, R.H.; Lazer, D.; Ognyanova, K.; Baum, M.; Santillana, M.; Druckman, J.; Volpe, J.D.; Quintana, A.; Chwe, H.; Simonson, M. The State of the Nation: A 50-State Covid-19 Survey Report #9: Will Americans Vaccinate Themselves and Their Children against Covid-19? Open Science Framework: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk Univeristy/USA Today Poll—Arizona; Suffolk University: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- University of Texas. University of Texas/Texas Tribune Poll—October 2020; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #200409; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. The Economist/YouGov Poll—20 October. YouGov, 20 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thigpen, C.; Funk, C. Most Americans expect a COVID-19 vaccine within a year; 72% say they would get vaccinated. Pew Research Center, 21 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #201087; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, M. Seven in 10 Americans Willing to Get COVID-19 Vaccine, Survey Finds; Medical Xpress: Douglas, Isle of Man, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tufts University’s Research Group on Equity in Health, Wealth and Civic Engagement. Only 57 Percent of Americans Say They Would Get COVID-19; Tufts University: Medford, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.-F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S. One in Three Americans Would Not Get COVID-19 Vaccine; Gallup: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, M. A Trend That Worries Health Experts: As U.S. Gets Closer to COVID-19 Vaccine, Fewer People Say They’d Get One; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ognyanova, K.; Lazer, D.; Baum, M. The State of the Nation: A 50-State Covid-19 Survey, Report #13: Public Trust in Institutions and Vaccine Acceptance; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2020; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #2009146; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–460. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. Yahoo! News Coronavirus. YouGov, 6 May 2020; 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/308222/coronavirus-pandemic.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- YouGov. The Economist/YouGov Poll 29 July; YouGov: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan, T.; Moghtaderi, A.; Lueck, J.A.; Hotez, P.J.; Strych, U.; Dor, A.; Franklin Fowler, E.; Motta, M. Correlates and Disparities of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020; p. 20, ID 3667971. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M. Poll: Half of Marylanders say they wouldn’t get COVID-19 vaccine. Herald Mail Media, 13 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #200572; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–643. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Axios/Ipsos Poll—Wave 22. Ipsos, 24 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. The Economist/YouGov Poll 25 August; YouGov: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–339. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, A.; Johnson, C.; Funk, C. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine. Pew Research, 17 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thunstrom, L.; Ashworth, M.; Finnoff, D.; Newbold, S. Hesitancy Towards a COVID-19 Vaccine and Prospects for Herd Immunity. SSRN J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expectations for a COVID-19 Vaccine. AP-NORC; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimungal, C. Concerns over fast-tracked COVID-19 vaccine has Americans unsure about vaccination. YouGov, 15 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Harris Poll. The Harris Poll—Wave 31, 26 September 2020, p. 262. Available online: https://mailchi.mp/1cf34288e711/the-insight-latest-trends-from-the-harris-poll-304510 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Bean, M. 71% of Americans would likely get COVID-19 vaccine, survey finds. Becker’s Hospital Review, 1 June 2020. Available online: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/public-health/57-of-americans-say-controlling-virus-is-more-important-than-reopening-economy.html (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors Associated With US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, S. 79% of Americans Considering Getting Coronavirus Vaccine—With Some Strings Attached. ValuePenguin, 10 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grech, V.; Gauci, C.; Agius, S. Vaccine hesitancy among Maltese healthcare workers toward influenza and novel COVID-19 vaccination. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsos. Coronavirus misinformation and reckless behavior linked. Ipsos, 20 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #200797. Morning Consult, 29 July 2020; 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk University/USA Today Poll—Florida. Suffolk University/USA Today, 6 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. A survey of the American general population. Ipsos, 25 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ax, J.; Steenhuysen, J. Exclusive: A quarter of Americans are hesitant about a coronavirus vaccine—Reuters/Ipsos poll. Reuters, 21 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, G. Nearly 2 in 5 Adults Say They’ve Gotten a Flu Shot, and Another 1 in 4 Plan to Get One. Morning Consult, 27 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos. Newsy/Ipsos Poll—25 Septmeber 2020. Ipsos, 25 September 2020; 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. A CNN-SSRS poll—5 October 2020. CNN/SSRS Research, 5 October 2020; 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. ABC News/Ipsos Poll—7 May 2020. Scribd, 7 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Post. Washington Post-ABC News poll—1 June 2020. Washington Post, 1 June 2020; 13. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. CBS News Battleground Tracker—2–4 September 2020. YouGov, 2–4 September 2020; 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Axios/Ipsos Poll—Wave 26. Ipsos, 27 September 2020; 47. [Google Scholar]

- Newsroom, K.F.F. Poll: Most Americans Worry Political Pressure Will Lead to Premature Approval of a COVID-19 Vaccine. Half Say They Would Not Get a Free Vaccine Approved Before Election Day. In KFF; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Trump COVID diagnosis does little to change Americans’ behavior around the virus. Ipsos, 6 October 2020. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/axios-ipsos-coronavirus-index (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Ipsos. Axios/Ipsos Poll wave 27 (Oct 5)-Topline and Methodology. Ipsos. 2020. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-10/topline-axios-wave-27.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Ipsos. Two in three Americans likely to get coronavirus vaccine. Ipsos. 2020. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/abc-coronavirus-vaccine-2020 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Leys, T. Iowa Poll: Iowans are wearing masks more often to ward off the coronavirus, especially if they’re Democrats. Des. Moines Register, 26 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ed, S. Poll: Most Americans believe the Covid-19 vaccine approval process is driven by politics, not science. STAT News, 31 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. How the Coronavirus Outbreak Is Impacting Public Opinion; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #2008107; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–721. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. The Economist/YouGov Poll—12 October 2020. YouGov, 12 October 2020; 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pransky, N. Poll: Less Than a Third of America Will Rush to Get Coronavirus Vaccine. NBC San Diego, 2 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, G. Anthony Fauci’s Vaccine Guidance Most Likely to Encourage Voters to Get Vaccinated; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk University/USA Today Poll—Minnesota. Suffolk University, 24 September 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk University/USA Today Poll—Pennsylvania. Suffolk University, 19 October 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Suffolk University. Suffolk University/Boston Globe Poll—Maine. Boston Globe, 21 September 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.-L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol Med. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABC News. Reopening the country seen as greater risk among most Americans: POLL. ABC News, 8 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. Yahoo! News Coronavirus—14 July 2020. YouGov, 14 July 2020, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/1k48xabxox/20200714_yahoo_coronavirus_toplines.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Galvin, G. Over 1 in 4 Adults Say FDA’s COVID-19 Decisions Are Politically Influenced as Agency Faces Scrutiny; Morning Consult: Washintong, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov. Yahoo! News Coronavirus—30 July 2020. YouGov, 30 July 2020, pp. 1–185. Available online: https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/l9txxcxdi3/20200730_yahoo_coronavirus_crosstabs.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Tribune, P. University of Texas/Texas Tribune Poll—June 2020; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H.J.; de Figueiredo, A.; Xiahong, Z.; Schulz, W.S.; Verger, P.; Johnston, I.G.; Cook, A.R.; Jones, N.S. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine 2016, 12, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prematunge, C.; Corace, K.; McCarthy, A.; Nair, R.C.; Pugsley, R.; Garber, G. Factors influencing pandemic influenza vaccination of healthcare workers—A systematic review. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4733–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnich, A.; Cambiaggi, M.; Vasco, A.; Maraniello, L.; Ansaldi, F.; Baldo, V.; Bonanni, P.; Calabrò, G.E.; Costantino, C.; de Waure, C.; et al. Attitudes and Beliefs on Influenza Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from a Representative Italian Survey. Vaccines 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, L.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Cooper, L.A. Historical Insights on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, and Racial Disparities: Illuminating a Path Forward. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. COVID-19 hospitalization and death by race/ethnicity. In Centers for Disease Control. and Prevention; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, R.B.; Charles, E.J.; Mehaffey, J.H. Socioeconomic Status and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Related Cases and Fatalities. Public Health 2020, 189, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimuth, V.S.; Quinn, S.C.; Thomas, S.B.; Cole, G.; Zook, E.; Duncan, T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, B.R.; Mathis, C.C.; Woods, A.K. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. J. Cult. Divers. 2007, 14, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.; Gostin, L.O.; Williams, M.A. Is It Lawful and Ethical to Prioritize Racial Minorities for COVID-19 Vaccines? JAMA 2020, 324, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.R.; Valle, S.Y.D. A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Gender and Protective Behaviors in Response to Respiratory Epidemics and Pandemics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bish, A.; Yardley, L.; Nicoll, A.; Michie, S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: A systematic review. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6472–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, S.; Kwong, J.C.; Buckeridge, D.L. The determinants of 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 influenza vaccination: A systematic review. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgaertner, B.; Ridenhour, B.J.; Justwan, F.; Carlisle, J.E.; Miller, C.R. Risk of disease and willingness to vaccinate in the United States: A population-based survey. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, G.L.; Clark, S.J.; Butchart, A.T.; Singer, D.C.; Davis, M.M. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brooks, D.J.; Saad, L. The COVID-19 Responses of Men vs. Women. Gallup, 7 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bish, A.; Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol 2010, 15, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martin, R. FDA COVID-19 Vaccine Process Is ‘Thoughtful And Deliberate,’ Says Former FDA Head. NPR, 23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.; Wu, K.J.; Thomas, K. Tells States How to Prepare for Covid-19 Vaccine by Early November. The New York Times, 3 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, W. Officials gird for a war on vaccine misinformation. Science 2020, 369, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, P. Anti-vaccine movement could undermine efforts to end coronavirus pandemic, researchers warn. Nature 2020, 581, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Weiland, N.; LaFraniere, S. Pharma Companies Plan Joint Pledge on Vaccine Safety. The New York Times, 4 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bulik, B.S. Pharma’s reputation gains persist through pandemic, bolstered by vaccine makers’ pledge: Harris Poll. FiercePharma, 24 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A. GlaxoSmithKline CEO Walmsley: COVID-19 is pharma’s chance for redemption. FiercePharma, 30 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, C.; Cotton, D.; Moyer, D.V. COVID-19 Vaccine: What Physicians Need to Know. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAteer, J.; Yildirim, I.; Chahroudi, A. The VACCINES Act: Deciphering Vaccine Hesitancy in the Time of COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis 2020, 71, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Vigue, D. US government slow to act as anti-vaxxers spread lies on social media about coronavirus vaccine. CNN, 13 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, O.; Berry, C.; Kumar, N. Addressing Parental Vaccine Hesitancy towards Childhood Vaccines in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review of Communication Interventions and Strategies. Vaccines 2020, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttenheim, A.M. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Acceptance: We May Need to Choose Our Battles. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-J.; Mesch, G.S. The Adoption of Preventive Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China and Israel. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, N.; Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H.; Gunaratne, K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer DeRoo, S.; Pudalov, N.J.; Fu, L.Y. Planning for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program. JAMA 2020, 323, 2458–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostler, T.J.; Wood, C.; Armitage, C.J. The influence of emotional cues on prospective memory: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Cogn. Emot. 2018, 32, 1578–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. The Impact of Narrative Strategy on Promoting HPV Vaccination among College Students in Korea: The Role of Anticipated Regret. Vaccines 2020, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The University of British Columbia. Research Guides: Grey Literature for Health Sciences: Google and Google Scholar. Available online: https://guides.library.ubc.ca/greylitforhealth/greyliterature/advancedgoogle (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Freeman, C. Library Guides: Grey Literature: Finding Grey Literature. Monash University. Available online: https://guides.lib.monash.edu/grey-literature/findinggreyliterature (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Es, M.v. LibGuides: Grey Literature: Using Google to Get Started. University of Otago. Available online: https://otago-med.libguides.com/greylit/google (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Wieber, F.; Thürmer, J.L.; Gollwitzer, P.M. Promoting the translation of intentions into action by implementation intentions: Behavioral effects and physiological correlates. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #200271; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–353. [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult. National Tracking Poll #200395; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 133. Harris Poll. Harris Poll Covid-19 Survey Wave 8. Harris Poll, 20 April 2020; 1–257.

- CNN. A CNN-SSRS poll—12 May 2020. SSRS, 12 May 2020; 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters/Ipsos. Reuters/Ipsos Core Political: Coronavirus Tracker. Ipsos, 22 March 2020; 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaran, V. 6 in 10 voters say they’ll get a coronavirus vaccine shot when it’s available, Fox News Poll finds. Fox News, 27 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. Axios/Ipsos Poll wave 18—Topline and Methodology. Ipsos, 27 July 2020; 33. [Google Scholar]

- 138. NPR/PBS NewsHour. NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll: 3–11 August. The Marist Poll, 14 October 2020; 1–63.

- Fox News. Fox News Poll—13 August 2020. Fox News, 13 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. A CNN-SSRS poll—19 August 2020. CNN, 19 August 2020; 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- KFF. KFF Health Tracking Poll—September 2020. KFF, 10 September 2020; 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Chicago Harris Public Policy. Americans Split on U.S. Role in Combatting Coronavirus and Relationship with Russia; The Associated Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- NPR/PBS NewsHour. NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll Results: Election 2020 & President Trump—11–16 September. NPR/PBS NewsHour, 18 September 2020; 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. ABC News/Ipsos Poll-Topline & Methodology, 19 September. Ipsos, 19 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goucher College. Goucher College Poll results: Maryland residents divided on taking a coronavirus vaccine; Majority support pace of reopening, but concerns over contracting virus remain. Goucher College, 13 October 2020; 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Warren, K.; Rhinesmith, E. Top. Line Results for October 2020 SLU/YouGov Poll; Saint Louis University: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, E. STAT-Harris Poll: The share of Americans interested in getting COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible is dropping. STAT News, 19 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016

Lin C, Tu P, Beitsch LM. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines. 2021; 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Cheryl, Pikuei Tu, and Leslie M. Beitsch. 2021. "Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review" Vaccines 9, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016

APA StyleLin, C., Tu, P., & Beitsch, L. M. (2021). Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines, 9(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016