Abstract

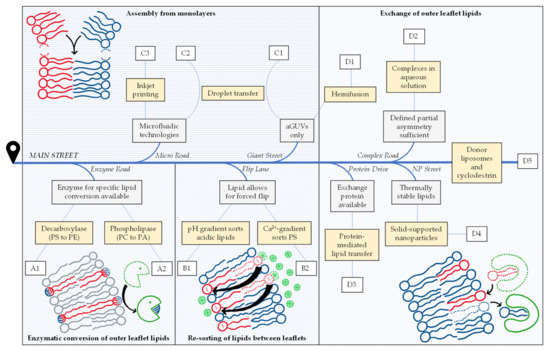

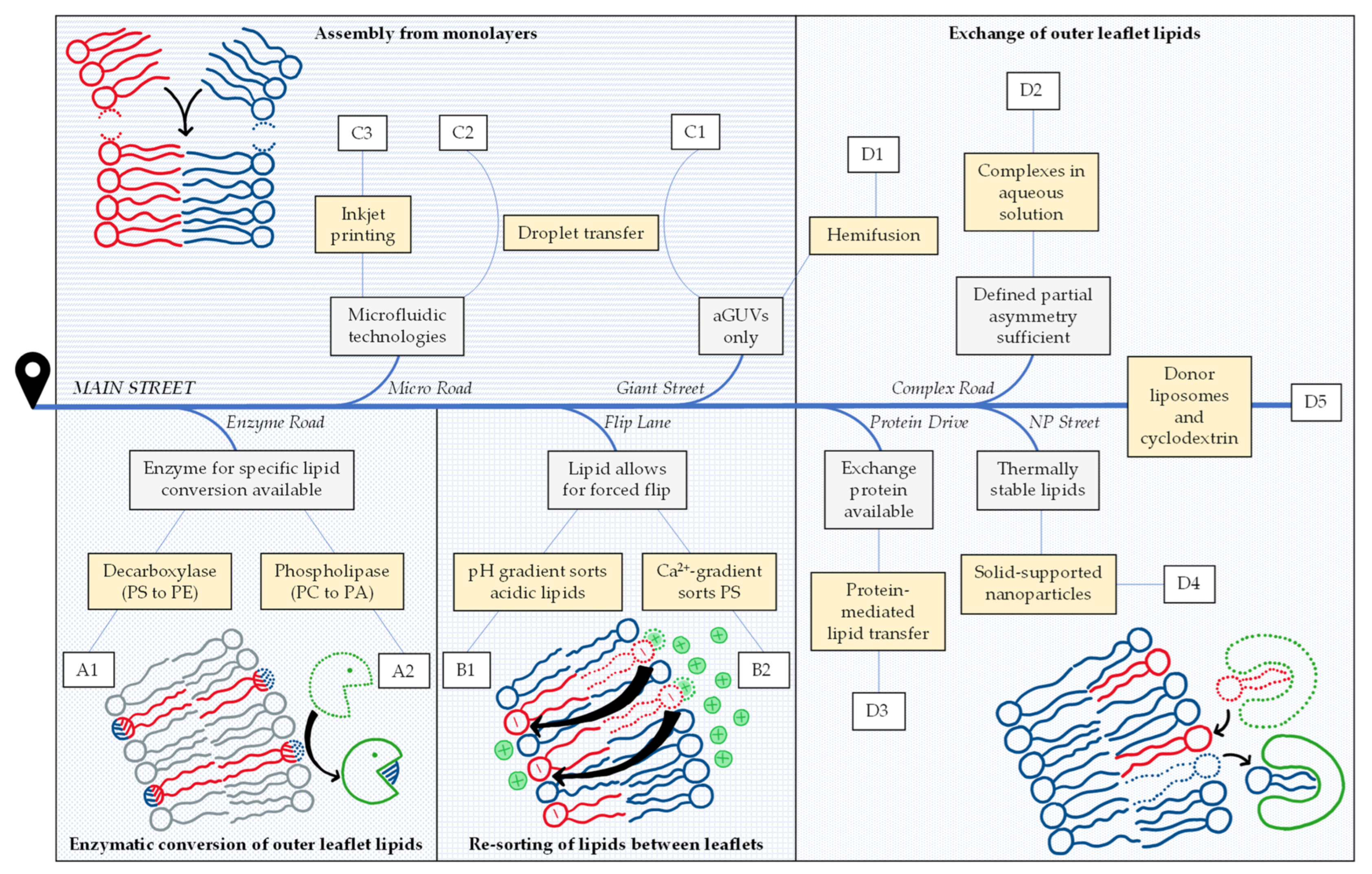

Liposomes are prevalent model systems for studies on biological membranes. Recently, increasing attention has been paid to models also representing the lipid asymmetry of biological membranes. Here, we review in-vitro methods that have been established to prepare free-floating vesicles containing different compositions of the classic two-chain glycero- or sphingolipids in their outer and inner leaflet. In total, 72 reports are listed and assigned to four general strategies that are (A) enzymatic conversion of outer leaflet lipids, (B) re-sorting of lipids between leaflets, (C) assembly from different monolayers and (D) exchange of outer leaflet lipids. To guide the reader through this broad field of available techniques, we attempt to draw a road map that leads to the lipid-asymmetric vesicles that suit a given purpose. Of each method, we discuss advantages and limitations. In addition, various verification strategies of asymmetry as well as the role of cholesterol are briefly discussed. The ability to specifically induce lipid asymmetry in model membranes offers insights into the biological functions of asymmetry and may also benefit the technical applications of liposomes.

1. Aims and Content of This Review

For decades, it has been known that most biological, lipid-bilayer based membranes are asymmetric in containing other lipids in the outer than in the inner membrane leaflet [1]. The considerable effort of an organism to establish, maintain, and adapt this asymmetry implies important biological functions [2]. However, since virtually all model membranes used in biophysical and biochemical studies were symmetric, these functions have remained largely unclear. Over the last few years, this long-term shortcoming has been overcome by a large-scale effort to establish and apply new, asymmetric membrane models.

Our review of this highly dynamic field has two main aims. First, we attempt at compiling all assays and protocols to prepare free-floating, lipid-asymmetric vesicles of the classic two-chain, glycero- or sphingolipids reported so far. Table 1 compiles the impressive number of 72 reports differing in strategy or lipid composition that we were able to find. Second, our paper aims at sorting these strategies and protocols into different principal categories and offering a road map that might help with finding the right protocol for a given purpose. For the sake of keeping this paper short and focused, we excluded other, certainly also very interesting membrane models such as asymmetric black lipid membranes, droplet interface bilayers, supported lipid bilayers, multicompartment vesicles, hybrid polymer-lipid vesicles and plasma membrane vesicles, and we did not list work on other lipidic compounds such as ceramides, gangliosides, lyso-lipids or lipopolysaccharides. Finally, we compile the applications as reported, for example a method demonstrated for asymmetric giant unilamellar vesicles (aGUVs) only, and abstain from speculation whether and how existing methods could be adapted or developed to serve other purposes in the future. Of course, such developments are expectable.

Excellent, alternative reviews that focus on other aspects of the field are available. Some articles address the production and application of GUVs in particular [3,4,5,6,7]. Dimova et al. focused on the preparation of aGUVs, in particular their observation by optical microscopy [3]. Reports about the preparation of aGUVs also include various microfluidic-based technologies [5,6,7,8,9]. Huang et al. described microfluidic emulsification in terms of microfluidic fabrication of single, double, triple or higher-order emulsion drops [8]. Kamiya and coworkers [5,6] discussed several techniques based on microfluidics for GUV formation. They summarized the properties of each method, including effects on encapsulation efficiency, size range and asymmetry of membranes. In addition, they described the formation of complex structures in terms of fabricating artificial cell models [5,6]. Cespedes et al. [10] reviewed the interplay between membrane components and the physical properties of the plasma membrane. Their report is outstanding for its focus on the immunological synapse [10]. London and coworkers mainly reviewed cyclodextrin-based methods for preparing asymmetric liposomes [11,12]. Besides this, Kakuda et al. [11] summarized studies about pore-forming toxins, such as perfringolysin O (PFO), regarding lipid interactions in symmetric and asymmetric vesicles [11]. In another article, studies about the effects of asymmetry on the ability of membranes to form ordered domains are summarized [12]. Scott et al. [13] recently reviewed experimental and computational techniques to study membrane asymmetry. Their focus was on in vitro methods that have advanced the understanding of the plasma membrane, along with molecular dynamics simulations. Different techniques for the fabrication of large and giant vesicles are described, i.e. via Ca2+-ions, enzymes and cyclodextrins. With respect to GUV preparation, i.e. hemifusion and phase-transfer approaches are described [13].

Overviewing the different strategies compiled in Table 1, we state that most start with symmetric vesicles and render them asymmetric in another preparation step. This may be achieved by enzymatic conversion of one lipid species into another one (A), by inducing the flip or flop of a given lipid species to accumulate in one leaflet (B), or by exchanging lipids in the outer leaflet (D). A fundamentally different approach is to assemble the vesicle bilayer from individual monolayers from scratch (C). These four fundamental strategies are pursued by many different protocols which all have their specific requirements, limitations, benefits and drawbacks.

3. Testing Asymmetry

Establishing and, to a large degree, safely employing a protocol to establish lipid asymmetry requires a means to quantify asymmetry. The choice of a validation method is not connected to the preparation protocol and hence, not within the scope of this review. But to give an overview, we will briefly take a look at the different strategies.

An ideal method to quantify the transmembrane distribution of a single charged lipid is the precise measurement of the zeta potential. It utilizes the fact that the low dielectric permittivity of the membrane core renders the charges in the inner leaflet invisible without any additional quenching or labeling as needed for other methods. Zeta potential measurement provides a label-free and non-destructive assay for asymmetry verification. It should be noted that experience and non-standard procedures or accessories such as high-concentration or dip cells might be needed to ensure that the zeta measurement reaches the necessary precision.

Fluorescence is a very versatile technique and fluorescence can be quenched selectively in the outer leaflet. However, usually high amounts of quencher must be used, resulting in increased osmolarities outside the liposomes. Annexin-V assay is suitable for specific quantification of PS lipids in the outer leaflet. It is a very sensitive technique but the sample cannot be used for further analysis. Fluorescence anisotropy can be used for studies of lipid order. Other options include fluorescence microscopy, which is suitable solely for testing GUVs.

It should be noted that the presence of fluorophores attached to lipids changes some of their properties crucially. This limits the applicability to asymmetric vesicles. For example, it essentially disqualifies fluorescent lipids from being proper models of unlabeled lipids for flip-flop studies.

NMR with shift reagents detects the fraction of a lipid species that is accessible from outside. Scattering techniques (SANS, SAXS) require or profit from deuterium labelling, which should be less intrusive to membrane properties than fluorophores. Mass spectrometry, optionally combined with other analytical methods such as gas chromatography, enables the analysis of molar masses, i.e. isotopically asymmetric labelled lipids. However, destruction of the sample has to be accepted.

4. Cholesterol

A membrane component outside the defined scope of lipids discussed here but of key interest for model membranes is cholesterol. Biological membranes, such as erythrocyte membranes, contain considerably larger amounts of cholesterol in their outer leaflet. Unlike the phospholipids discussed so far, cholesterol undergoes a fast flip-flop across the membrane so that its distribution is essentially equilibrated. Asymmetry is imposed by the facts that (I) the outer leaflet contains more unsaturated (sphingo)lipids with high cholesterol affinity than the inner and (II) the outer leaflet contains lesser phospholipid (intrinsic area) all together, giving way to the area requirement of additional cholesterol.

Together with mixing entropy opposing asymmetry, these properties give rise to cholesterol asymmetry [90,91]. It appears that creating sphingomyelin- and area asymmetry would be a means to establish a proper cholesterol asymmetry in a model membrane.

Two strategies should be possible to avoid cholesterol to interfere with cyclodextrin-based protocols for phospholipid asymmetry. First, α-cyclodextrins may be more challenging for lipid transfer but do not complex cholesterol. Hence, lipids can be handled selectively in the presence of cholesterol. Second, β-cyclodextrins bind cholesterol primarily with a stoichiometry of 2:1 but phospholipids with 4:1; given the binding constants, it needs relatively low cyclodextrin concentrations (of the order of 5–10 mM mβCD) to transport cholesterol [92] but higher cyclodextrin concentrations of about 30–50 mM to extract significant amounts of lipid [93]. Hence, one could in principle deal with the lipids first, at high cyclodextrin, and then add cholesterol using low cyclodextrin. The issue remains, though, that a relaxed lipid membrane with matching intrinsic areas of the outside and inside lipids will also incorporate cholesterol in a largely symmetrical manner to avoid asymmetry stress.

5. Outlook

Hoping the reader can forgive our roadmap story one more time, it needs to be reiterated that there is heavy construction going on in the country we reviewed. A new freeway or a new settlement in one area may suddenly redirect traffic and render Main Street a neglected place. In a foreseeable future, there shall be several alternative protocols available for every simple model of interest and time will have to tell which of them become standard. At some point, using symmetric vesicles for a model study may become as unpopular with reviewers as it happened with DMPC as generic membrane model some decades ago. More sophisticated types of asymmetry as exemplified for cholesterol will become accessible at some point.

From our perspective, it would be useful to agree on a uniform definition of lipid asymmetry in the future. The column regarding degree of asymmetry in Table 1. shows that 14 different definitions of asymmetry are present. To date, there have been a number of attempts to define lipid asymmetry more clearly. We previously introduced an asymmetry parameter a that comprises the amount of asymmetrically distributed lipid, i.e. PS, and ranges from −1 (all-inside localization of PS) via 0 (symmetric distribution) to 1 (outside-only PS) [15]. Guo et al. described the asymmetric degree a of PS molecules in the membrane based on its monolayer concentration in the inner and outer bilayer leaflet [27]. Eicher et al. defined asymmetry, ∑as, as the difference of donor lipid mole fraction in the outer and inner leaflet [66]. Another approach defines Pa% as percentage of lipid exchange in asymmetric vesicles with regard to symmetric and asymmetric vesicles [45,46,47].

The above mentioned, varying and in some cases lacking definitions of lipid asymmetry demonstrate the need for a uniform specification to improve comparability of the large number of methods for preparation of liposomes.

Another aspect of interest and potential for further investigation is the asymmetry stability issue. In individual cases, if specifically highlighted in the article concerned, we have already mentioned asymmetry stability in chapter two (see above). That topic receives varying levels of attention; while in some protocol asymmetry is confirmed for at least a few hours, others provide stability data over several days. Again, it is not trivial to compare data of different methods and systems.

We tried our best to compile a selection of optimal protocols based on what the individual papers are providing. In the future, it will be important to have comparative reports of one laboratory having tested different protocols to serve a given purpose. This will give rise to improved, dedicated roadmaps for a vehicle of interest.

We now slowly start getting rewarded for using asymmetric models by learning about the functions of lipid asymmetry in biology and its potential use for technical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and H.H.; investigation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and H.H.; visualization, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the wonderfully collaborative, open-minded and friendly spirit of the lipid asymmetry community. In particular, we dedicate this contribution to Georg’s “asymmetry roundtable” held on skype long before we all became online-conference experts. It successfully ignored that we all were supposed to behave as competitors and this way, became a liveable Utopia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marquardt, D.; Geier, B.; Pabst, G. Asymmetric lipid membranes: Towards more realistic model systems. Membranes 2015, 5, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, R.J.; Hossain, K.R.; Cao, K. Physiological roles of transverse lipid asymmetry of animal membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, R.; Aranda, S.; Bezlyepkina, N.; Nikolov, V.; Riske, K.A.; Lipowsky, R. A practical guide to giant vesicles. Probing the membrane nanoregime via optical microscopy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S1151–S1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walde, P.; Cosentino, K.; Engel, H.; Stano, P. Giant Vesicles: Preparations and Applications. ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 848–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Takeuchi, S. Giant liposome formation toward the synthesis of well-defined artificial cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 5911–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K. Development of artificial cell models using microfluidic technology and synthetic biology. Micromachines 2020, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.C.; Malmstadt, N. Asymmetric Giant Lipid Vesicle Fabrication. Methods Membr. Lipids Second Ed. 2014, 1232, 1–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Arriaga, L.R. Emulsion templated vesicles with symmetric or asymmetric membranes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 247, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Xie, R.; Xiong, J.; Liang, Q. Microfluidics for Biosynthesizing: From Droplets and Vesicles to Artificial Cells. Small 2020, 16, e1903940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, P.F.; Beckers, D.; Dustin, M.L.; Sezgin, E. Model membrane systems to reconstitute immune cell signaling. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 1070–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakuda, S.; Li, B.; London, E. Preparation and Utility of Asymmetric Lipid Vesicles for Studies of Perfringolysin O-Lipid Interactions, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 649, ISBN 9780128238585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, E. Ordered Domain (Raft) Formation in Asymmetric Vesicles and Its Induction upon Loss of Lipid Asymmetry in Artificial and Natural Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, H.L.; Kennison, K.B.; Enoki, T.A.; Doktorova, M.; Kinnun, J.J.; Heberle, F.A.; Katsaras, J. Model Membrane Systems Used to Study Plasma Membrane Lipid Asymmetry. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaoka, R.; Kurosaki, H.; Nakao, H.; Ikeda, K.; Nakano, M. Formation of asymmetric vesicles via phospholipase D-mediated transphosphatidylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, C.; Markones, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Frieling, N.; Fiedler, S.; Voelker, D.R.; Schubert, R.; Heerklotz, H. Preparation of Asymmetric Liposomes Using a Phosphatidylserine Decarboxylase. Biophys. J. 2018, 115, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkins, Y.M.; Schroit, A.J. Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase: Generation of asymmetric vesicles and determination of the transbilayer distribution of fluorescent phosphatidylserine in model membrane systems. BBA-Biomembr. 1986, 862, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, K.H.; Bartoldus, I.; Stegmann, T. Membrane asymmetry is maintained during influenza-induced fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 2383–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.D.; Harrigan, P.R.; Tai, L.C.L.; Bally, M.B.; Mayer, L.D.; Redelmeier, T.E.; Loughrey, H.C.; Tilcock, C.P.S.; Reinish, L.W.; Cullis, P.R. The accumulation of drugs within large unilamellar vesicles exhibiting a proton gradient: A survey. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1990, 53, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, S.J.; Hope, M.J.; Wong, K.F.; Cullis, P.R. Influence of Phospholipid Asymmetry on Fusion Between Large Unilamellar Esicles. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 4262–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.L.; Cullis, P.R. Modulation of Membrane Fusion by Asymmetric Transbilayer Distributions of Amino Lipids. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 12573–12580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, M.J.; Redelmeier, T.E.; Wong, K.F.; Rodrigueza, W.; Cullis, P.R. Phospholipid Asymmetry in Large Unilamellar Vesicles Induced by Transmembrane pH Gradients. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 4181–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redelmeier, T.E.; Hope, M.J.; Cullis, P.R. On the Mechanism of Transbilayer Transport of Phosphatidylglycerol in Response to Transmembrane pH Gradients. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 3046–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilcock, C.; Eastman, S.; Fisher, D. Induction of lipid asymmetry and exchange in model membrane systems. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1991, 12, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farge, E.; Devaux, P.F. Shape changes of giant liposomes induced by an asymmetric transmembrane distribution of phospholipids. Biophys. J. 1992, 61, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Tachibana, K. NMR observation on transbilayer distribution of N-[13C]methylated chlorpromazine in asymmetric lipid bilayer of unilamellar vesicles. Chem. Lett. 2000, 29, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Deng, G.; Jiang, Y.W.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.G.; Yu, Z.W. Controllable engineering of asymmetric phosphatidylserine-containing lipid vesicles using calcium cations. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12762–12765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Deng, G.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.G.; Yu, Z.W. Fabrication of asymmetric phosphatidylserine-containing lipid vesicles: A study on the effects of size, temperature, and lipid composition. Langmuir 2020, 36, 12684–12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautot, S.; Frisken, B.J.; Weitz, D.A. Engineering Asymmetric Vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10718–10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautot, S.; Frisken, B.J.; Weitz, D.A. Production of unilamellar vesicles using an inverted emulsion. Langmuir 2003, 19, 2870–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.C.; Li, S.; Malmstadt, N. Microfluidic fabrication of asymmetric giant lipid vesicles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matosevic, S.; Paegel, B.M. Layer-by-layer cell membrane assembly. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Schertzer, J.W.; Chiarot, P.R. Continuous microfluidic fabrication of synthetic asymmetric vesicles. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 3591–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, L.R.; Huang, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Aragones, J.L.; Ziblat, R.; Koehler, S.A.; Weitz, D.A. Single-step assembly of asymmetric vesicles. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanov, V.; McCullough, J.; Gale, B.K.; Frost, A. A Tunable Microfluidic Device Enables Cargo Encapsulation by Cell- or Organelle-Sized Lipid Vesicles Comprising Asymmetric Lipid Bilayers. Adv. Biosyst. 2019, 3, 1900010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabi, S.; Malmstadt, N.; Schertzer, J.W.; Chiarot, P.R. An integrated microfluidic platform to fabricate single-micrometer asymmetric giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) using dielectrophoretic separation of microemulsions. Biomicrofluidics 2021, 15, 024112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, D.L.; Schmid, E.M.; Martens, S.; Stachowiak, J.C.; Liska, N.; Fletcher, D.A. Forming giant vesicles with controlled membrane composition, asymmetry, and contents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9431–9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K.; Kawano, R.; Osaki, T.; Akiyoshi, K.; Takeuchi, S. Cell-sized asymmetric lipid vesicles facilitate the investigation of asymmetric membranes. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotanda, M.; Kamiya, K.; Osaki, T.; Fujii, S.; Misawa, N.; Miki, N.; Takeuchi, S. Sequential generation of asymmetric lipid vesicles using a pulsed-jetting method in rotational wells. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2018, 261, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Osaki, T.; Takeuchi, S. Formation of nano-sized lipid vesicles with asymmetric lipid components using a pulsed-jet flow method. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2021, 327, 128917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Arisaka, C.; Suzuki, M. Investigation of fusion between nanosized lipid vesicles and a lipid monolayer toward formation of giant lipid vesicles with various kinds of biomolecules. Micromachines 2021, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, T.; Miura, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Kishimoto, Y.; Vestergaard, M.; Takagi, M. Construction of asymmetric cell-sized lipid vesicles from lipid-coated water-in-oil microdroplets. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 14678–14681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Doak, W.J.; Schertzer, J.W.; Chiarot, P.R. Membrane mechanical properties of synthetic asymmetric phospholipid vesicles. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 7521–7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamdad, K.; Law, R.V.; Seddon, J.M.; Brooks, N.J.; Ces, O. Studying the effects of asymmetry on the bending rigidity of lipid membranes formed by microfluidics. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 5277–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elani, Y.; Purushothaman, S.; Booth, P.J.; Seddon, J.M.; Brooks, N.J.; Law, R.V.; Ces, O. Measurements of the effect of membrane asymmetry on the mechanical properties of lipid bilayers. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6976–6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoki, T.A.; Feigenson, G.W. Asymmetric Bilayers by Hemifusion: Method and Leaflet Behaviors. Biophys. J. 2019, 117, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enoki, T.A.; Wu, J.; Heberle, F.A.; Feigenson, G.W. Investigation of the domain line tension in asymmetric vesicles prepared via hemifusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoki, T.A.; Feigenson, G.W. Improving our picture of the plasma membrane: Rafts induce ordered domains in a simplified model cytoplasmic leaflet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2022, 1864, 183995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markones, M.; Drechsler, C.; Kaiser, M.; Kalie, L.; Heerklotz, H.; Fiedler, S. Engineering Asymmetric Lipid Vesicles: Accurate and Convenient Control of the Outer Leaflet Lipid Composition. Langmuir 2018, 34, 1999–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markones, M.; Fippel, A.; Kaiser, M.; Drechsler, C.; Hunte, C.; Heerklotz, H. Stairway to Asymmetry: Five Steps to Lipid-Asymmetric Proteoliposomes. Biophys. J. 2020, 118, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroff, J.T.; Dietzen, N.M.; Santiago-McRae, E.; Deng, B.; Washington, M.S.; Chen, L.J.; Trent Moreland, K.; Deng, Z.; Rau, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.J.; et al. Open-channel structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel reveals a mechanism of leaflet-specific phospholipid modulation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, A.A.P.; Schleiff, E.; Röhring, C.; Loidl-Stahlhofen, A.; Vergères, G. Interactions of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS)- related protein with a novel solid-supported lipid membrane system (TRANSIL). Anal. Biochem. 1999, 268, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinl, H.M.; Bayerl, T.M. Lipid Transfer between Small Unilamellar Vesicles and Single Bilayers on a Solid Support: Self-Assembly of Supported Bilayers with Asymmetric Lipid Distribution. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 14091–14099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kelley, E.G.; Batchu, K.C.; Porcar, L.; Perez-Salas, U. Creating Asymmetric Phospholipid Vesicles via Exchange with Lipid-Coated Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2020, 36, 8865–8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Iwamoto, M.; Kato, A.; Yoshikawa, K.; Oiki, S. Oriented reconstitution of a membrane protein in a giant unilamellar vesicle: Experimental verification with the potassium channel KcsA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11774–11779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perillo, V.L.; Peñalva, D.A.; Vitale, A.J.; Barrantes, F.J.; Antollini, S.S. Transbilayer asymmetry and sphingomyelin composition modulate the preferential membrane partitioning of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Lo domains. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 591, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kruijff, B.; Wirtz, K.W.A. Induction of a relatively fast transbilayer movement of phosphatidylcholine in vesicles. A 13C NMR study. BBA-Biomembr. 1977, 468, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, J.; Zlotnick, A.; Tennyson, J.; Holloway, P.W. Fluorescence quenching of cytochrome b5 in vesicles with an asymmetric transbilayer distribution of brominated phosphatidylcholine. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 6725–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandra, A.; Pagano, R.E. Liposome-cell interactions. Studies of lipid transfer using isotopically asymmetric vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 2244–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, M.; Momm, J.; Schubert, R. Lipid transfer mediated by a recombinant pro-sterol carrier protein 2 for the accurate preparation of asymmetrical membrane vesicles requires a narrow vesicle size distribution: A free-flow electrophoresis study. Langmuir 2010, 26, 4142–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquardt, D.; Heberle, F.A.; Miti, T.; Eicher, B.; London, E.; Katsaras, J.; Pabst, G. 1H NMR Shows Slow Phospholipid Flip-Flop in Gel and Fluid Bilayers. Langmuir 2017, 33, 3731–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.T.; Megha; London, E. Preparation and properties of asymmetric vesicles that mimic cell membranes. Effect upon lipid raft formation and transmembrane helix orientation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 6079–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberle, F.A.; Marquardt, D.; Doktorova, M.; Geier, B.; Standaert, R.F.; Heftberger, P.; Kollmitzer, B.; Nickels, J.D.; Dick, R.A.; Feigenson, G.W.; et al. Subnanometer Structure of an Asymmetric Model Membrane: Interleaflet Coupling Influences Domain Properties. Langmuir 2016, 32, 5195–5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doktorova, M.; Heberle, F.A.; Eicher, B.; Standaert, R.F.; Katsaras, J.; London, E.; Pabst, G.; Marquardt, D. Preparation of asymmetric phospholipid vesicles for use as cell membrane models. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 2086–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, T.; Ikeda, K.; Nakano, M. Kinetic Analysis of the Methyl-β-cyclodextrin-Mediated Intervesicular Transfer of Pyrene-Labeled Phospholipids. Langmuir 2016, 32, 13697–13705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher, B.; Heberle, F.A.; Marquardt, D.; Rechberger, G.N.; Katsaras, J.; Pabst, G. Joint small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering data analysis of asymmetric lipid vesicles. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2017, 50, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher, B.; Marquardt, D.; Heberle, F.A.; Letofsky-Papst, I.; Rechberger, G.N.; Appavou, M.S.; Katsaras, J.; Pabst, G. Intrinsic Curvature-Mediated Transbilayer Coupling in Asymmetric Lipid Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, K.C.; Pezeshkian, W.; Raghupathy, R.; Zhang, C.; Darbyson, A.; Ipsen, J.H.; Ford, D.A.; Khandelia, H.; Presley, J.F.; Zha, X. C24 Sphingolipids Govern the Transbilayer Asymmetry of Cholesterol and Lateral Organization of Model and Live-Cell Plasma Membranes. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doktorova, M.; Heberle, F.A.; Marquardt, D.; Rusinova, R.; Sanford, R.L.; Peyear, T.A.; Katsaras, J.; Feigenson, G.W.; Weinstein, H.; Andersen, O.S. Gramicidin Increases Lipid Flip-Flop in Symmetric and Asymmetric Lipid Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickeard, B.W.; Nguyen, M.H.L.; Dipasquale, M.; Yip, C.G.; Baker, H.; Heberle, F.A.; Zuo, X.; Kelley, E.G.; Nagao, M.; Marquardt, D. Transverse lipid organization dictates bending fluctuations in model plasma membranes. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.L.; Heberle, F.A.; Katsaras, J.; Barrera, F.N. Phosphatidylserine Asymmetry Promotes the Membrane Insertion of a Transmembrane Helix. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, L.; Frewein, M.P.K.; Semeraro, E.F.; Rechberger, G.N.; Lohner, K.; Porcar, L.; Pabst, G. Antimicrobial peptide activity in asymmetric bacterial membrane mimics. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 232, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewein, M.P.K.; Piller, P.; Semeraro, E.F.; Batchu, K.C.; Heberle, F.A.; Scott, H.L.; Gerelli, Y.; Porcar, L.; Pabst, G. Interdigitation-Induced Order and Disorder in Asymmetric Membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 2022, 255, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiantia, S.; Schwille, P.; Klymchenko, A.S.; London, E. Asymmetric GUVs prepared by MβCD-mediated lipid exchange: An FCS study. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, L1–L3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.T.; London, E. Preparation and properties of asymmetric large unilamellar vesicles: Interleaflet coupling in asymmetric vesicles is dependent on temperature but not curvature. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2671–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiantia, S.; London, E. Acyl Chain length and saturation modulate interleaflet coupling in asymmetric bilayers: Effects on dynamics and structural order. Biophys. J. 2012, 103, 2311–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; London, E. The dependence of lipid asymmetry upon phosphatidylcholine acyl chain structure. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petazzi, R.A.; Gramatica, A.; Herrmann, A.; Chiantia, S. Time-controlled phagocytosis of asymmetric liposomes: Application to phosphatidylserine immunoliposomes binding HIV-1 virus-like particles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; London, E. Preparation of artificial plasma membrane mimicking vesicles with lipid asymmetry. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; London, E. The influence of natural lipid asymmetry upon the conformation of a membrane-inserted protein (perfringolysin O). J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 5467–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; London, E. Ordered raft domains induced by outer leaflet sphingomyelin in cholesterol-rich asymmetric vesicles. Biophys. J. 2015, 108, 2212–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; London, E. Lipid Structure and Composition Control Consequences of Interleaflet Coupling in Asymmetric Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2018, 115, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Clair, J.W.; London, E. Effect of sterol structure on ordered membrane domain (raft) stability in symmetric and asymmetric vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; London, E. Preparation and drug entrapment properties of asymmetric liposomes containing cationic and anionic lipids. Langmuir 2020, 36, 12521–12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Raleigh, D.P.; London, E. Preparation of Asymmetric Vesicles with Trapped CsCl Avoids Osmotic Imbalance, Non-Physiological External Solutions, and Minimizes Leakage. Langmuir 2021, 37, 11611–11617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epand, R.F.; Martinou, J.C.; Montessuit, S.; Epand, R.M. Transbilayer Lipid Diffusion Promoted by Bax: Implications for Apoptosis. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14576–14582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konetski, D.; Zhang, D.; Schwartz, D.K.; Bowman, C.N. Photoinduced Pinocytosis for Artificial Cell and Protocell Systems. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 8757–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, A.; Sofou, S. Daptomycin-Induced Lipid Phases on Model Lipid Bilayers: Effect of Lipid Type and of Lipid Leaflet Order on Membrane Permeability. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 5775–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miwa, A.; Kamiya, K. Control of Enzyme Reaction Initiation inside Giant Unilamellar Vesicles by the Cell-Penetrating Peptide-Mediated Translocation of Cargo Proteins. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozelli, J.C.; Hou, Y.H.; Schreier, S.; Epand, R.M. Lipid asymmetry of a model mitochondrial outer membrane affects Bax-dependent permeabilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, M.; Deserno, M. Distribution of cholesterol in asymmetric membranes driven by composition and differential stress. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 4001–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doktorova, M.; Levental, I. Cholesterol’s balancing act: Defying the status quo. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 3771–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsamaloukas, A.; Szadkowska, H.; Slotte, P.J.; Heerklotz, H. Interactions of cholesterol with lipid membranes and cyclodextrin characterized by calorimetry. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.G.; Tan, A.; Ganz, P.; Seelig, J. Calorimetric Measurement of Phospholipid Interaction with Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 2251–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).