Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

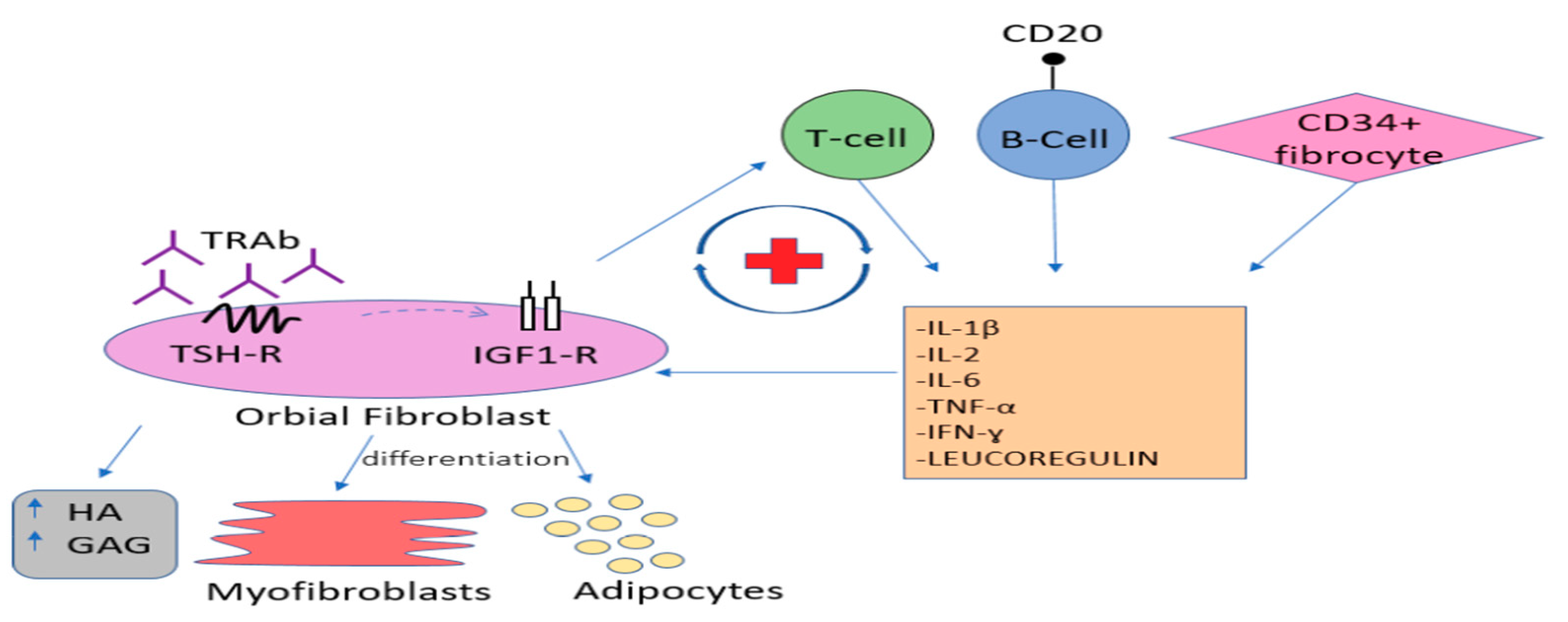

2. Etiopathogenesis

3. Risk Factors

4. Clinical Picture and Diagnosis

5. Clinical Classification

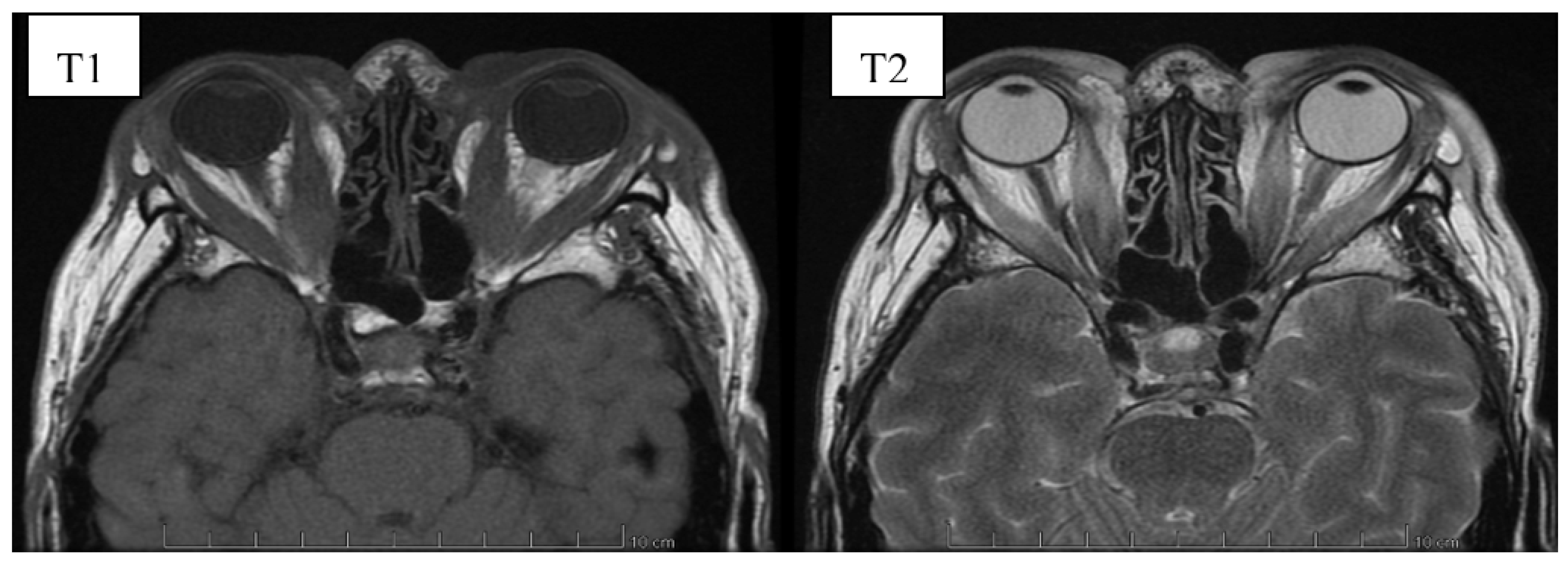

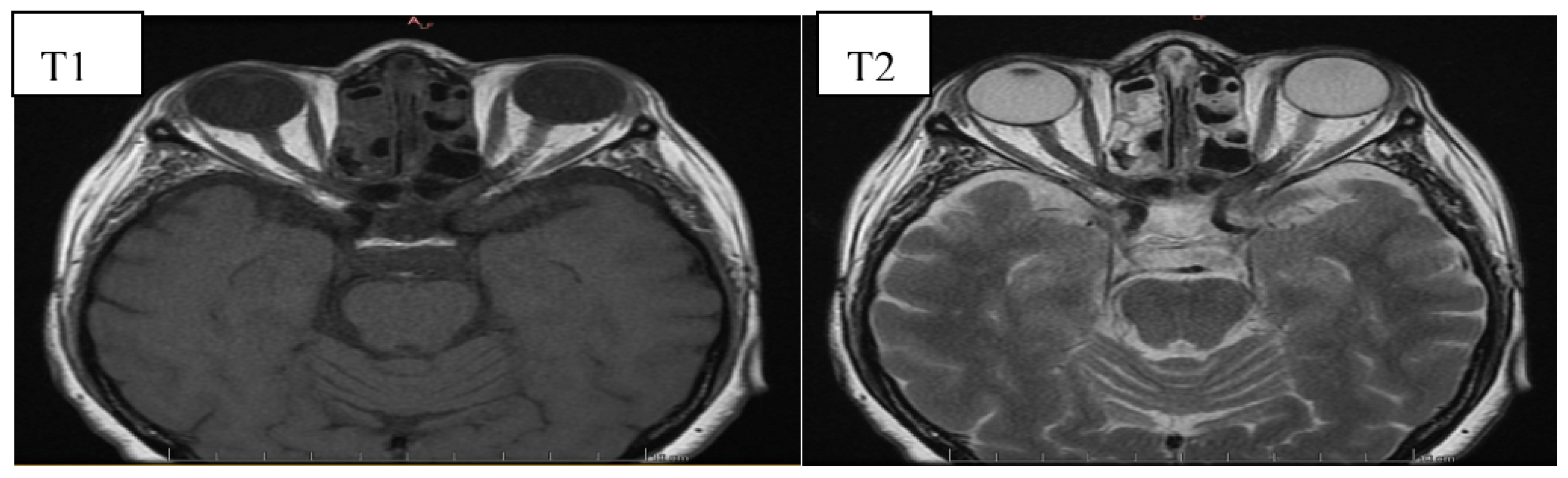

6. Image Evaluation

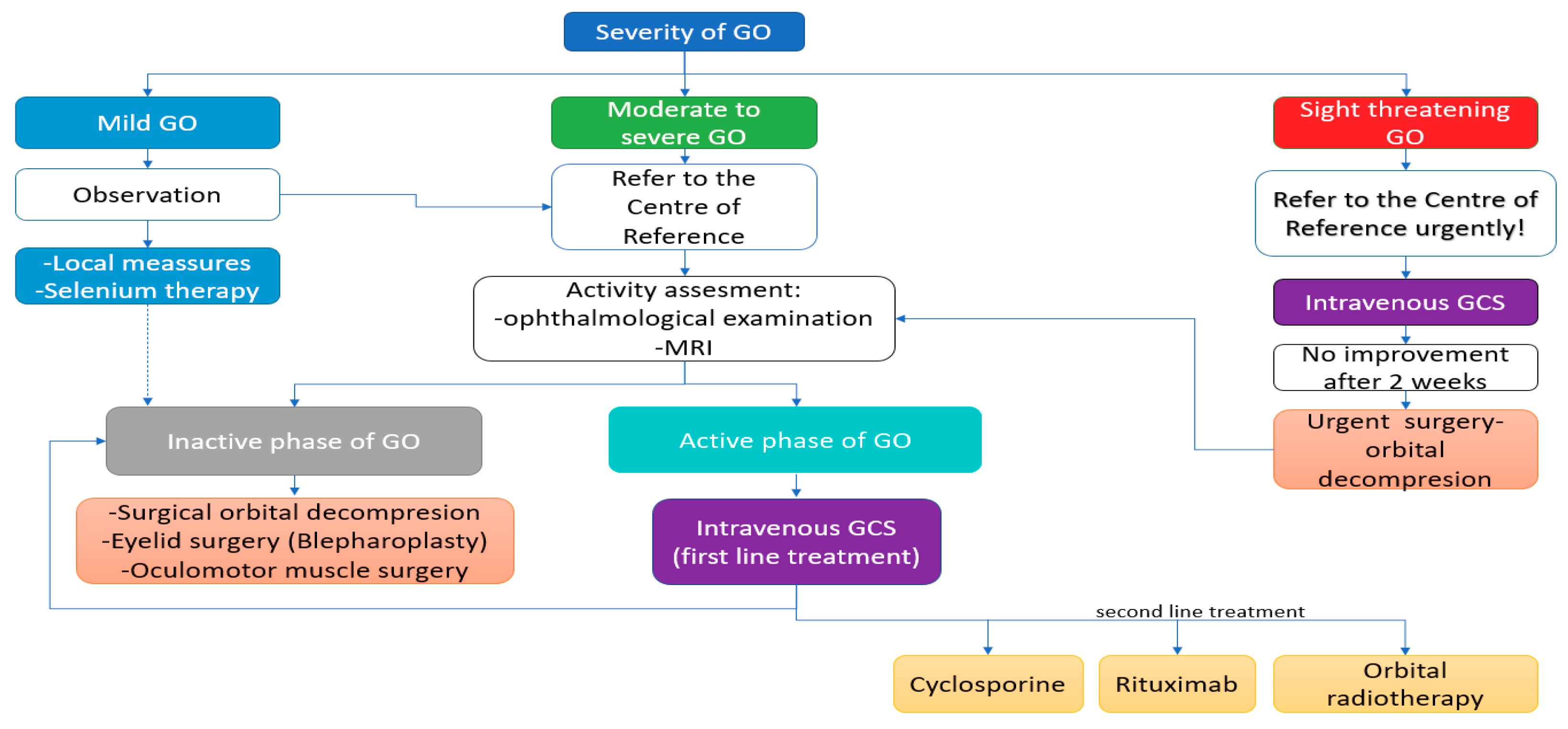

7. Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy

7.1. Modifiable Risk Factors

7.2. General Principles of GO Management

- -

- Artificial tears containing osmoprotective agents, such as sodium hyaluronate, with moisturizing eye drops should be applied regularly to alleviate symptoms of corneal irritation;

- -

- Gels or ointments may be required in cases of significant corneal exposure, mainly at night;

- -

- Protective glasses with an ultraviolet (UV) filter;

- -

- Anti-inflammatory and antibacterial ointments in case of bacterial infection;

- -

- Raising the head higher during sleep in order to reduce morning eyelid swelling.

7.3. Treatment of Mild GO

- -

- The use of 100 μg of selenium twice a day for 6 months in active mild GO of recent onset was effective in re-ducing eye symptoms and improving quality of life, which is attributed to the anti-inflammatory and antioxi-dant properties of this element. Moreover, a long-term therapeutic effect after discontinuation of the treatment and a lower incidence of progression to more severe forms of GO were observed [59]. However, it should be emphasized that these data were obtained from a study performed in marginally selenium-deficient areas of Europe. Whether similar beneficial effects of selenium can be observed in GO patients in selenium replete areas has to be investigated.

- -

- Subconjunctival botulinum toxin injections to reduce retraction of the upper eyelid (especially effective in pa-tients in the active phase of the disease, when the final surgical correction should not be performed yet) [60].

7.4. General Principles of GO Management

7.4.1. Active Moderate-to-Severe GO-Glucocorticotherapy—First Line Treatment

- -

- Diabetes—metabolically uncontrolled diabetes is a contraindication to GCs treatment,

- -

- Uncontrolled resistant arterial hypertension, severe arrhythmias, unstable ischemic heart disease, severe heart failure are contraindications to GCs treatment,

- -

- Liver function disorders—a 4–5-fold increase in the activity of liver enzymes is a contraindication to the treatment; moreover, it is necessary to exclude viral hepatitis, and according to some authors, also autoim-mune hepatitis before introducing systemic GCs therapy,

- -

- Glaucoma—a complete ophthalmological examination, including measurement of IOP should be performed both before and after a treatment cycle, because GCs increase IOP. However, it should be noted that an in-crease in IOP in GO may also result from the underlying disease,

- -

- Infection markers (blood count, CRP and urinalysis). GCs treatment should be postponed in the case of bacteri-al, viral or fungal infections,

- -

- Osteoporosis—it is recommended to perform densitometry before long-term (>3 months) treatment with GCs. Moreover, the EUGOGO suggests supplementation with vitamin D3, calcium and the use of anti-resorptive drugs during systemic steroid therapy, especially in patients with multiple risk factors for osteoporosis

- -

- Peptic ulcer disease—especially important among patients on chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Proton pump inhibitors are recommended during GCs treatment.

- -

- Mental disorders—according to some authors, severe mental illnesses are a contraindication to GCs therapy.

7.4.2. Active Moderate-to-Severe GO—Second Line Treatment

Radiotherapy on the Orbital Cavities

Cyclosporine

Rituximab (RTX)

7.4.3. Alternative Treatments with Potential Efficacy

Somatostatin Analogues (SSAs)

Azathioprine

Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF)

Methotrexate (MTX)

Tocilizumab (TCZ)

TNF-Alpha Inhibitors

Teprotumumab

7.4.4. Supplementary Treatment

Statins

Enalapril

Pentoxifylline

7.4.5. Inactive Moderate-to-Severe GO—Surgical Treatment

7.5. Treatment of Sight-Threatening GO

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartalena, L.; Baldeschi, L.; Dickinson, A.; Eckstein, A.; Kendall-Taylor, P.; Marcocci, C.; Mourits, M.; Perros, P.; Boboridis, K.; Boschi, A.; et al. Consensus statement of the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of GO. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 158, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanda, M.L.; Piantanida, E.; Liparulo, L.; Veronesi, G.; Lai, A.; Sassi, L.; Pariani, N.; Gallo, D.; Azzolini, C.; Ferrario, M.; et al. Prevalence and natural history of Graves’ orbitopathy in a large series of patients with newly diagnosed graves’ hyperthyroidism seen at a single center. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hiromatsu, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Tani, J.; Kasaoka, M.; Teshima, Y. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Epidemiology and Natural History. Intern. Med. 2014, 53, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Villadolid, M.C.; Yokoyama, N.; Izumi, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Kimura, H.; Ashizawa, K.; Kiriyama, T.; Uetani, M.; Nagataki, S. Untreated Graves’ disease patients without clinical ophthalmopathy demonstrate a high frequency of extraocular muscle (EOM) enlargement by magnetic resonance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 2830–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.M.; Bartalena, L. Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 2002, 12, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perros, P.; Dayan, C.M.; Dickinson, A.J.; Ezra, D.; Estcourt, S.; Foley, P.; Hickey, J.; Lazarus, J.H.; MacEwen, C.J.; McLaren, J.; et al. Management of patients with Graves’ orbitopathy: Initial assessment, management outside specialised centres and referral pathways. Clin. Med. 2015, 15, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Petrak, F.; Hardt, J.; Pitz, S.; Egle, U.T. Psychosocial morbidity of Graves’ orbitopathy. Clin. Endocrinol. 2005, 63, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.M. Management of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 3, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourits, M.P.; Koornneef, L.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Prummel, M.F.; Berghout, A.; van der Gaag, R. Clinical criteria for the assessment of disease activity in Graves’ ophthalmopathy: A novel approach. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1989, 73, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiersinga, W.M.; Smit, T.; van der Gaag, R.; Koornneef, L. Temporal relationship between onset of Graves’ ophthalmopathy and onset of thyroidal Graves’ disease. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1988, 11, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, D.H.; Eng, P.H.; Ho, S.C.; Tai, E.S.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Seah, L.L.; Fong, K.S.; Chee, S.P.; Choo, C.T.; Aw, S.E. Graves’ ophthalmopathy in the absence of elevated free thyroxine and triiodothyronine levels: Prevalence, natural history, and thyrotropin receptor antibody levels. Thyroid 2000, 10, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerding, M.N.; van der Meer, J.W.; Broenink, M.; Bakker, O.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Prummel, M.F. Association of thyrotrophin receptor antibodies with the clinical features of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Clin. Endocrinol. 2000, 52, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytton, S.D.; Ponto, K.A.; Kanitz, M.; Matheis, N.; Kohn, L.D.; Kahaly, G.J. A novel thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin bioassay is a functional indicator of activity and severity of Graves’ orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2123–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Patel, A.; Douglas, R.S. Thyroid Eye Disease: How a Novel Therapy May Change the Treatment Paradigm. Available online: https://www.dovepress.com/thyroid-eye-disease-how-a-novel-therapy-may-change-the-treatment-parad-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-TCRM (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Wang, Y.; Smith, T.J. Current concepts in the molecular pathogenesis of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bahn, R.S. Current Insights into the Pathogenesis of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Horm. Metab. Res. 2015, 47, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weightman, D.R.; Perros, P.; Sherif, I.H.; Kendall-Taylor, P. Autoantibodies to Igf-1 Binding Sites in Thyroid Associated Ophthalmopathy. Autoimmunity 1993, 16, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, S.; Naik, V.; Hoa, N.; Hwang, C.J.; Afifiyan, N.F.; Sinha Hikim, A.; Gianoukakis, A.G.; Douglas, R.S.; Smith, T.J. Evidence for an association between thyroid-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors: A tale of two antigens implicated in Graves’ disease. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 4397–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.S.; Gianoukakis, A.G.; Kamat, S.; Smith, T.J. Aberrant expression of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor by T cells from patients with Graves’ disease may carry functional consequences for disease pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 3281–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.; Han, R.; Horst, N.; Cruikshank, W.W.; Smith, T.J. Immunoglobulin activation of T cell chemoattractant expression in fibroblasts from patients with Graves’ disease is mediated through the insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 6348–6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minich, W.B.; Dehina, N.; Welsink, T.; Schwiebert, C.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Köhrle, J.; Eckstein, A.; Schomburg, L. Autoantibodies to the IGF1 receptor in Graves’ orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, T.J.; Kahaly, G.J.; Ezra, D.G.; Fleming, J.C.; Dailey, R.A.; Tang, R.A.; Harris, G.J.; Antonelli, A.; Salvi, M.; Goldberg, R.A.; et al. Teprotumumab for Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stan, M.N.; Bahn, R.S. Risk Factors for Development or Deterioration of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 2010, 20, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahn, R.S. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khalilzadeh, O.; Noshad, S.; Rashidi, A.; Amirzargar, A. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Review of Immunogenetics. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kendler, D.L.; Lippa, J.; Rootman, J. The Initial Clinical Characteristics of Graves’ Orbitopathy Vary With Age and Sex. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1993, 111, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, H.B.; Wartofsky, L. Graves’ ophthalmopathy: Current concepts regarding pathogenesis and management. Endocr. Rev. 1993, 14, 747–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tellez, M.; Cooper, J.; Edmonds, C. Graves’ ophthalmopathy in relation to cigarette smoking and ethnic origin. Clin. Endocrinol. 1992, 36, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, C.-L.; Seah, L.L.; Khoo, D.H.C. Ethnic differences in the clinical presentation of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, J.J.; Finch, S.; De Silva, C.; Rylander, S.; Craig, J.E.; Selva, D.; Ebeling, P.R. Risk Factors for Graves’ Orbitopathy; the Australian Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy Research (ATOR) Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 2711–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roos, J.C.P.; Paulpandian, V.; Murthy, R. Serial TSH-receptor antibody levels to guide the management of thyroid eye disease: The impact of smoking, immunosuppression, radio-iodine, and thyroidectomy. Eye 2019, 33, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalmann, R.; Mourits, M.P. Diabetes mellitus: A risk factor in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prummel, M.F.; Wiersinga, W.M. Smoking and risk of Graves’ disease. JAMA 1993, 269, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, A.; Quadbeck, B.; Mueller, G.; Rettenmeier, A.W.; Hoermann, R.; Mann, K.; Steuhl, P.; Esser, J. Impact of smoking on the response to treatment of thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartalena, L.; Marcocci, C.; Tanda, M.L.; Manetti, L.; Dell’Unto, E.; Bartolomei, M.P.; Nardi, M.; Martino, E.; Pinchera, A. Cigarette Smoking and Treatment Outcomes in Graves Ophthalmopathy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 129, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnywojtek, A.; Komar-Rychlicka, K.; Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak, M.; Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Woliński, K.; Gut, P.; Płazinska, M.; Torlińska, B.; Florek, E.; Waligórska-Stachura, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of radioiodine therapy for mild Graves ophthalmopathy depending on cigarette consumption: A 6-month follow-up. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2016, 126, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.; Stan, M. Current and Future Treatments for Graves’ Disease and Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Horm. Metab. Res. 2018, 50, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prummel, M.F.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Mounts, M.P.; Koornneef, L.; Berghout, A.; van der Gaag, R. Effect of Abnormal Thyroid Function on the Severity of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Arch. Intern. Med. 1990, 150, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolman, P.J. Evaluating Graves’ orbitopathy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Barrio, J.; Sabater, A.L.; Bonet-Farriol, E.; Velázquez-Villoria, Á.; Galofré, J.C. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: VISA versus EUGOGO Classification, Assessment, and Management. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 2015, 249125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiersinga, W.M.; Perros, P.; Kahaly, G.J.; Mourits, M.P.; Baldeschi, L.; Boboridis, K.; Boschi, A.; Dickinson, A.J.; Kendall-Taylor, P.; Krassas, G.E.; et al. Clinical assessment of patients with Graves’ orbitopathy: The European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy recommendations to generalists, specialists and clinical researchers. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 155, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werner, S.C. Modification of the classification of the eye changes of Graves’ disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1977, 83, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.P.; Gebrim, E.M.M.S.; Monteiro, M.L.R. Imaging studies for diagnosing Graves’ orbitopathy and dysthyroid optic neuropathy. Clinics 2012, 67, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J. Imaging in thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2001, 145, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Forell, W.; Kahaly, G.J. Neuroimaging of Graves’ orbitopathy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakirer, S.; Cakirer, D.; Basak, M.; Durmaz, S.; Altuntas, Y.; Yigit, U. Evaluation of extraocular muscles in the edematous phase of Graves ophthalmopathy on contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed magnetic resonance imaging. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2004, 28, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, E.; Hammer, B. Graves’orbitopathy: Current imaging procedures. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2009, 139, 618–623. [Google Scholar]

- Vlainich, A.R.; Romaldini, J.H.; Pedro, A.B.; Farah, C.S.; Sinisgalli, C.A., Jr. Ultrasonography compared to magnetic resonance imaging in thyroid-associated Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2011, 55, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieb, W.E.; Cohen, S.M.; Merton, D.A.; Shields, J.A.; Mitchell, D.G.; Goldberg, B.B. Color Doppler Imaging of the Eye and Orbit: Technique and Normal Vascular Anatomy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1991, 109, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.L.R.; Moritz, R.B.S.; Angotti Neto, H.; Benabou, J.E. Color Doppler imaging of the superior ophthalmic vein in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy before and after treatment of congestive disease. Clinics 2011, 66, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerding, M.N.; van der Zant, F.M.; van Royen, E.A.; Koornneef, L.; Krenning, E.P.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Prummel, M.F. Octreotide-scintigraphy is a disease-activity parameter in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Clin. Endocrinol. 1999, 50, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, C.; Li, X.; Tan, J.; Deng, Z. 99mTc-DTPA SPECT/CT provided guide on triamcinolone therapy in Graves’ ophthalmopathy patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartalena, L.; Baldeschi, L.; Boboridis, K.; Eckstein, A.; Kahaly, G.J.; Marcocci, C.; Perros, P.; Salvi, M.; Wiersinga, W.M. The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy Guidelines for the Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Eur. Thyroid J. 2016, 5, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartalena, L.; Marcocci, C.; Bogazzi, F.; Manetti, L.; Tanda, M.L.; Dell’Unto, E.; Bruno-Bossio, G.; Nardi, M.; Bartolomei, M.P.; Lepri, A.; et al. Relation between Therapy for Hyperthyroidism and the Course of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiber, S.; Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Shimon, I.; Grossman, A.; Robenshtok, E. Glucocorticoid regimens for prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy progression following radioiodine treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 2014, 24, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bellis, A.; Conzo, G.; Cennamo, G.; Pane, E.; Bellastella, G.; Colella, C.; Iacovo, A.D.; Paglionico, V.A.; Sinisi, A.A.; Wall, J.R.; et al. Time course of Graves’ ophthalmopathy after total thyroidectomy alone or followed by radioiodine therapy: A 2-year longitudinal study. Endocrine 2012, 41, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bahn Chair, R.S.; Burch, H.B.; Cooper, D.S.; Garber, J.R.; Greenlee, M.C.; Klein, I.; Laurberg, P.; McDougall, I.R.; Montori, V.M.; Rivkees, S.A.; et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: Management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid 2011, 21, 593–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menconi, F.; Profilo, M.A.; Leo, M.; Sisti, E.; Altea, M.A.; Rocchi, R.; Latrofa, F.; Nardi, M.; Vitti, P.; Marcocci, C.; et al. Spontaneous Improvement of Untreated Mild Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Rundle’s Curve Revisited. Thyroid 2014, 24, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marcocci, C.; Kahaly, G.J.; Krassas, G.E.; Bartalena, L.; Prummel, M.; Stahl, M.; Altea, M.A.; Nardi, M.; Pitz, S.; Boboridis, K.; et al. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nava Castañeda, A.; Tovilla Canales, J.L.; Garnica Hayashi, L.; Velasco Y Levy, A. Management of upper eyelid retraction associated with dysthyroid orbitopathy during the acute inflammatory phase with botulinum toxin type A. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2017, 40, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcocci, C.; Bartalena, L.; Panicucci, M.; Marconcini, C.; Cartei, F.; Cavallacci, G.; Laddaga, M.; Campobasso, G.; Baschieri, L.; Pinchera, A. Orbital cobalt irradiation combined with retrobulbar or systemic corticosteroids for Graves’ ophthalmopathy: A comparative study. Clin. Endocrinol. 1987, 27, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen-Mäkelin, R.; Karma, A.; Leinonen, E.; Löyttyniemi, E.; Salonen, O.; Sane, T.; Setälä, K.; Viikari, J.; Heufelder, A.; Välimäki, M. High dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy versus oral prednisone for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2002, 80, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Pitz, S.; Hommel, G.; Dittmar, M. Randomized, single blind trial of intravenous versus oral steroid monotherapy in Graves’ orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 5234–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zang, S.; Ponto, K.A.; Kahaly, G.J. Intravenous Glucocorticoids for Graves’ Orbitopathy: Efficacy and Morbidity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, W.; Ye, L.; Shen, L.; Jiao, Q.; Huang, F.; Han, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Ning, G. A Prospective, Randomized Trial of Intravenous Glucocorticoids Therapy With Different Protocols for Patients With Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eichhorn, K.; Harrison, A.R.; Bothun, E.D.; McLoon, L.K.; Lee, M.S. Ocular treatment of thyroid eye disease. Expert Rev. Ophthalmol. 2010, 5, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, P.; Kryczka, A.; Ambroziak, U.; Rutkowska, B.; Główczyńska, R.; Opolski, G.; Kahaly, G.; Bednarczuk, T. Is high dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy safe? Endokrynol. Pol. 2014, 65, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolman, P.J.; Rath, S. Orbital radiotherapy for thyroid eye disease. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2012, 23, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, M.; Sabater, S.; Hernández, V.; Rovirosa, A.; Lara, P.C.; Biete, A.; Panés, J. Anti-inflammatory effects of low-dose radiotherapy. Indications, dose, and radiobiological mechanisms involved. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2012, 188, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, C.A.; Garrity, J.A.; Fatourechi, V.; Bahn, R.S.; Petersen, I.A.; Stafford, S.L.; Earle, J.D.; Forbes, G.S.; Kline, R.W.; Bergstralh, E.J.; et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of orbital radiotherapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prummel, M.F.; Berghout, A.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Mourits, M.P.; Koornneef, L.; Blank, L. Randomised double-blind trial of prednisone versus radiotherapy in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Lancet 1993, 342, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.M.; Yuen, H.K.L.; Choi, K.L.; Chan, M.K.; Yuen, K.T.; Ng, Y.W.; Tiu, S.C. Combined orbital irradiation and systemic steroids compared with systemic steroids alone in the management of moderate-to-severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy: A preliminary study. Hong Kong Med. J. 2005, 11, 322–330. [Google Scholar]

- Mourits, M.P.; van Kempen-Harteveld, M.L.; García, M.B.G.; Koppeschaar, H.P.; Tick, L.; Terwee, C.B. Radiotherapy for Graves’ orbitopathy: Randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2000, 355, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Rösler, H.P.; Pitz, S.; Hommel, G. Low-Versus High-Dose Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Randomized, Single Blind Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 102–108. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/85/1/102/2852174 (accessed on 2 July 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Miguel, I.; Arenas, M.; Carmona, R.; Rutllan, J.; Medina-Rivero, F.; Lara, P. Review of the treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: The role of the new radiation techniques. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 32, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartalena, L.; Marcocci, C.; Tanda, M.L.; Rocchi, R.; Mazzi, B.; Barbesino, G.; Pinchera, A. Orbital Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 2002, 12, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihatsch, M.J.; Kyo, M.; Morozumi, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nickeleit, V.; Ryffel, B. The side-effects of ciclosporine-A and tacrolimus. Clin. Nephrol. 1998, 6, 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- Kahaly, G.; Schrezenmeir, J.; Krause, U.; Schweikert, B.; Meuer, S.; Muller, W.; Dennebaum, R.; Beyer, J. Ciclosporin and prednisone v. prednisone in treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: A controlled, randomized and prospective study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1986, 16, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prummel, M.F.; Mourits, M.P.; Berghout, A.; Krenning, E.P.; van der Gaag, R.; Koornneef, L.; Wiersinga, W.M. Prednisone and cyclosporine in the treatment of severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 321, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emer, J.J.; Claire, W. Rituximab. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2009, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, J.; Jankiewicz-Wika, J.; Siejka, A.; Lawnicka, H.; Stepień, H. Anti-cytokine and anti-lymphocyte monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski. 2007, 22, 571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Salvi, M.; Vannucchi, G.; Currò, N.; Campi, I.; Covelli, D.; Dazzi, D.; Simonetta, S.; Guastella, C.; Pignataro, L.; Avignone, S.; et al. Efficacy of B-cell targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with active moderate to severe Graves’ orbitopathy: A randomized controlled study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stan, M.N.; Garrity, J.A.; Carranza Leon, B.G.; Prabin, T.; Bradley, E.A.; Bahn, R.S. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartalena, L.; Pinchera, A.; Marcocci, C. Management of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Reality and Perspectives. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 168–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, A.W.; Michon, J.; Tai, K.S.; Chan, F.L. The effect of somatostatin versus corticosteroid in the treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 1996, 6, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, K.; Kulig, G. Lanreotide in the treatment of thyroid orbitopathy. Prz. Lek. 2004, 61, 845–847. [Google Scholar]

- Le, M.R.; Castoro, C.; Mouritz, M.; Souters, M. Pasireotide and Graves; BioScientifica: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendram, R.; Taylor, P.N.; Wilson, V.J.; Harris, N.; Morris, O.C.; Tomlinson, M.; Yarrow, S.; Garrott, H.; Herbert, H.M.; Dick, A.D.; et al. Combined immunosuppression and radiotherapy in thyroid eye disease (CIRTED): A multicentre, 2 × 2 factorial, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, A.C. Mechanisms of action of mycophenolate mofetil. Lupus 2005, 14, s2–s8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Bo, X.; Hu, X.; Cui, H.; Lu, B.; Shao, J.; Wang, J. Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with active moderate-to-severe Graves’ orbitopathy. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 86, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Riedl, M.; König, J.; Pitz, S.; Ponto, K.; Diana, T.; Kampmann, E.; Kolbe, E.; Eckstein, A.; Moeller, L.C.; et al. Mycophenolate plus methylprednisolone versus methylprednisolone alone in active, moderate-to-severe Graves’ orbitopathy (MINGO): A randomised, observer-masked, multicentre trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Naime, D.; Ostad, E. The antiinflammatory mechanism of methotrexate. Increased adenosine release at inflamed sites diminishes leukocyte accumulation in an in vivo model of inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 92, 2675–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yong, K.-L.; Chng, C.-L.; Ming Sie, N.; Lang, S.; Yang, M.; Looi, A.; Choo, C.-T.; Shen, S.; Seah, L.L. Methotrexate as an Adjuvant in Severe Thyroid Eye Disease: Does It Really Work as a Steroid-Sparing Agent? Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 35, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, V.; Dhillon, S.; Plosker, G.L. Tocilizumab. Drugs 2009, 69, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Moreiras, J.V.; Alvarez-López, A.; Gómez, E.C. Treatment of active corticosteroid-resistant graves’ orbitopathy. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 30, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffe, B.; Cather, J.C. Etanercept: An overview. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paridaens, D.; van den Bosch, W.A.; van der Loos, T.L.; Krenning, E.P.; van Hagen, P.M. The effect of etanercept on Graves’ ophthalmopathy: A pilot study. Eye 2005, 19, 1286–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Douglas, R.S.; Kahaly, G.J.; Patel, A.; Sile, S.; Thompson, E.H.Z.; Perdok, R.; Fleming, J.C.; Fowler, B.T.; Marcocci, C.; Marinò, M.; et al. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA News Release. FDA Approves First Treatment for Thyroid Eye Disease. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-thyroid-eye-disease (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Jain, M.K.; Ridker, P.M. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Statins: Clinical Evidence and Basic Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G.; Sabini, E.; Profilo, M.A.; Mazzi, B.; Sframeli, A.; Rocchi, R.; Menconi, F.; Leo, M.; Nardi, M.; Vitti, P.; et al. Relationship between serum cholesterol and Graves’ orbitopathy (GO): A confirmatory study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2018, 41, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabini, E.; Mazzi, B.; Profilo, M.A.; Mautone, T.; Casini, G.; Rocchi, R.; Ionni, I.; Menconi, F.; Leo, M.; Nardi, M.; et al. High Serum Cholesterol Is a Novel Risk Factor for Graves’ Orbitopathy: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Thyroid 2018, 28, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.D.; Childers, D.; Gupta, S.; Talwar, N.; Nan, B.; Lee, B.J.; Smith, T.J.; Douglas, R. Risk factors for developing thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy among individuals with Graves disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G.; Vannucchi, G.; Ionni, I.; Campi, I.; Sileo, F.; Lazzaroni, E.; Marinò, M. Cholesterol Serum Levels and Use of Statins in Graves’ Orbitopathy: A New Starting Point for the Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifulco, M.; Ciaglia, E. Statin reduces orbitopathy risk in patients with Graves’ disease by modulating apoptosis and autophagy activities. Endocrine 2016, 53, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, A.L.; Monte, M.A.D.; Archer, S.M. The effect of oral statin therapy on strabismus in patients with thyroid eye disease. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatric Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2018, 22, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Ganten, D. The molecular basis of cardiovascular hypertrophy: The role of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1992, 19, S51–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, R.; Lisi, S.; Marcocci, C.; Sellari-Franceschini, S.; Rocchi, R.; Latrofa, F.; Menconi, F.; Altea, M.A.; Leo, M.; Sisti, E.; et al. Enalapril Reduces Proliferation and Hyaluronic Acid Release in Orbital Fibroblasts. Thyroid 2012, 23, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataabadi, G.; Dabbaghmanesh, M.H.; Owji, N.; Bakhshayeshkaram, M.; Montazeri-Najafabady, N. Clinical Features of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy and Impact of Enalapril on the Course of Mild Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Pilot Study. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/ben/emiddt/2020/00000020/00000001/art00016 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Rieneck, K.; Diamant, M.; Haahr, P.-M.; Schönharting, M.; Bendtzen, K. In vitro immunomodulatory effects of pentoxifylline. Immunol. Lett. 1993, 37, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chang, T.C.; Kao, S.C.; Kuo, Y.F.; Chien, L.F. Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxoedema. Acta Endocrinol. 1993, 129, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, C.; Kiss, E.; Vamos, A.; Molnar, I.; Farid, N.R. Beneficial Effect of Pentoxifylline on Thyroid Associated Ophthalmopathy (TAO): A pilot study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 1999–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, A.; Schittkowski, M.; Esser, J. Surgical treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, J.A. Orbital lipectomy (fat decompression) for thyroid eye disease: An operation for everyone? Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 151, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, J.; Eckstein, A. Ocular muscle and eyelid surgery in thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 1999, 107, S214–S221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakelkamp, I.M.M.J.; Baldeschi, L.; Saeed, P.; Mourits, M.P.; Prummel, M.F.; Wiersinga, W.M. Surgical or medical decompression as a first-line treatment of optic neuropathy in Graves’ ophthalmopathy? A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Endocrinol. 2005, 63, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | - In women GO is more frequent [26,27]. - In men GO is more severe [26]. |

| Race | - In Caucasians GO is more frequent than in Asians [29]. |

| Genetics | - Mostly similar to Graves’ disease [23]. - Some studies evaluated immunomodulatory genes including: human leukocyte antigen-DR3 (HLA-DR3), interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-23 receptor (IL-23R), CD40, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4), T-cell receptor β-chain (TCR-β), protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22), tumor necrosis factor-β (TNF-β) and numerous immunoglobulin heavy chain-associated genes [25]. - Due to the involvement of TSH-R into the patoghenesis of GO the TSH-R gene polymorphisms were studied [24]. However, none of the polymorphisms have proved adequately predictive to support genetic testing in determining prevention methods and further diagnostic and therapeutic process. - Moreover, the increased orbital adipogenesis in GO contributed to genetic testing of the adipogenesis-related gene peroxisome proliferator–associated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) [24]. |

| GD duration | - The longer duration of GD-related hyperthyroidism the higher risk of GO [30]. |

| Age | - Older age of GD onset is associated with higher risk of GO development [30]. - Older age of GO onset is associated with more severe course of the disease [26]. |

| Exogenous factors |

|

| Biochemical factors | - Thyroid dysfunction—both hyper and hypothyroidism—is associated with a greater risk of development, progression, and severe course of GO compared to euthyroid patients [38]. - High TSHR antibody titers increase the risk of GO development, positively correlate with the activity and severity of the disease and are a predictor of poor response to the to immunosuppressive treatment and the risk of relapse after treatment [31]. |

| Initial CAS Assessment, Scored by Points 1–7 | |

|---|---|

| Pain | 1 Spontaneous orbital pain 2. Gaze evoked orbital pain |

| Redness | 3. Eyelid erythema 4. Conjunctival redness that is considered due to active GO |

| Swelling | 5. Eyelid swelling 6. Chemosis 7. Inflammation of the caruncle or plica |

| Follow-Up CAS Assessment (after 1–3 Months Period), Scored by Points 1–10 | |

| Impaired function | 8. Decrease of eye movements in any direction above ≥5° (during a 1–3 months period) 9. Decrease of visual acuity of ≥1 line on the Snellen chart (during a 1–3 months period) |

| Proptosis | 10. Increase of proptosis ≥2 mm (during 1–3 months period) |

| Class | Abbreviation | Description | Detailed Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | N | No signs or symptoms | No complaints, No findings in physical examination (PE) |

| 1 | O | Only signs, no symptoms | No complains, PE: Eyelid retraction Stare |

| 2 | S | Soft tissue involvement | Swelling of eyelids Chemosis Photophobia Grittiness |

| 3 | P | Proptosis | Exophtalmus |

| 4 | E | Extraocular muscle involvement | Restricted eyeball mobility (often diplopia) |

| 5 | C | Corneal involvement | Keratitis, Corneal Ulcer |

| 6 | S | Sight loss | Decreased visual acuity, impaired color of vision (optic nerve involvement) |

| Sign/Symptom | Score |

|---|---|

| Caruncular edema | 0: Absent 1: Present |

| Chemosis | 0: Absent 1: Conjunctiva lies behind the grey line of the lid 2: Conjunctiva extends anterior to the grey line of the lid |

| Conjunctival redness | 0: Absent 1: Present |

| Lid redness | 0: Absent 1: Present |

| Lid edema | 0: Absent 1: Present but without redundant tissues 2: Present and causing bulging in the palpebral skin, including lower lid festoon |

| Retrobulbar ache: -At rest -With gaze | 0: Absent 1: Present |

| 0: Absent 1: Present | |

| Diurnal variation | 0: Absent 1: Present |

| Soft Tissues | Eyelid swelling 1. Absent 2. Mild: none of the features defining moderate or severe swelling are present 3. Moderate: definite swelling but no lower eyelid festoons and in the upper eyelid the skin fold becomes angled on a 45° downgaze 4. Severe: lower eyelid festoons or upper lid fold remains rounded on a 45° downgaze |

| Eyelid erythema 1. Absent 2. Present | |

| Conjunctival redness 1. Absent 2. Mild: equivocal or minimal redness 3. Moderate: <50% of definite conjunctival redness 4. Severe: >50% of definite conjunctival redness | |

| Conjunctival edema 1. Absent 2. Present: separation of conjunctiva from sclera present in >1/3 of the total height of the palpebral aperture or conjunctiva prolapsing anterior to grey line of eyelid | |

| Inflammation of caruncle or plica semilunaris 1. Absent 2. Present: plica is prolapsed through closed eyelids or caruncle and/or plica are inflamed | |

| Eyelid Measurements | Palpebral aperture (mm) |

| Upper/lower lid retraction (mm) | |

| Levator function (mm) | |

| Lagophthalmos 1. Absent 2. Present | |

| Bell’s phenomenon 1. Absent 2. Present | |

| Proptosis | Measurement with Hertel’s exophthalmometer. Recording of intercanthal distance. |

| Ocular Motility | Prism cover test Monocular ductions Head posture Torsion Field of binocular single vision |

| Cornea | Corneal integrity 1. Normal 2. Punctate keratopathy 3. Ulcer 4. Perforation |

| Optic Neuropathy | 1. Visual acuity (Logmar or Snellen) 2. Afferent pupil defect (present/absent) 3. Color vision 4. Optic disc assessment: normal/atrophy/edema |

| Mild | GO has a minor impact on the patient’s everyday life. They usually present one or more of the following signs: 1. Minor lid retraction (<2 mm) 2. Mild soft tissue involvement 3. Exophthalmos < 3 mm (above the normal range for the race and gender) 4. Transient or no diplopia 5. Corneal exposure with a good response to lubricants. |

| Moderate to severe | patients without sight-threatening GO whose eye disease has sufficient impact on daily life to justify the risks of immunosuppression (if active) or surgical intervention (if inactive). Patients usually present one or more of the following signs: 1. Lid retraction (>2 mm) 2. Moderate or severe soft tissue involvement 3. Exophthalmos ≥3 mm (above the normal range for the race and gender) 4. Inconstant, or constant diplopia. |

| Sight-threatening GO | Patients with dysthyroid optic neuropathy or corneal breakdown due to severe exposure. Other infrequent cases are ocular globe subluxation, severe forms of frozen eye, choroidal folds, and postural visual darkening. This category warrants immediate intervention. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gontarz-Nowak, K.; Szychlińska, M.; Matuszewski, W.; Stefanowicz-Rutkowska, M.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010016

Gontarz-Nowak K, Szychlińska M, Matuszewski W, Stefanowicz-Rutkowska M, Bandurska-Stankiewicz E. Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleGontarz-Nowak, Katarzyna, Magdalena Szychlińska, Wojciech Matuszewski, Magdalena Stefanowicz-Rutkowska, and Elżbieta Bandurska-Stankiewicz. 2021. "Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010016

APA StyleGontarz-Nowak, K., Szychlińska, M., Matuszewski, W., Stefanowicz-Rutkowska, M., & Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. (2021). Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010016