Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Recruitment and Patient Follow-Up

2.4. Definitions

2.5. Data Collection and Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

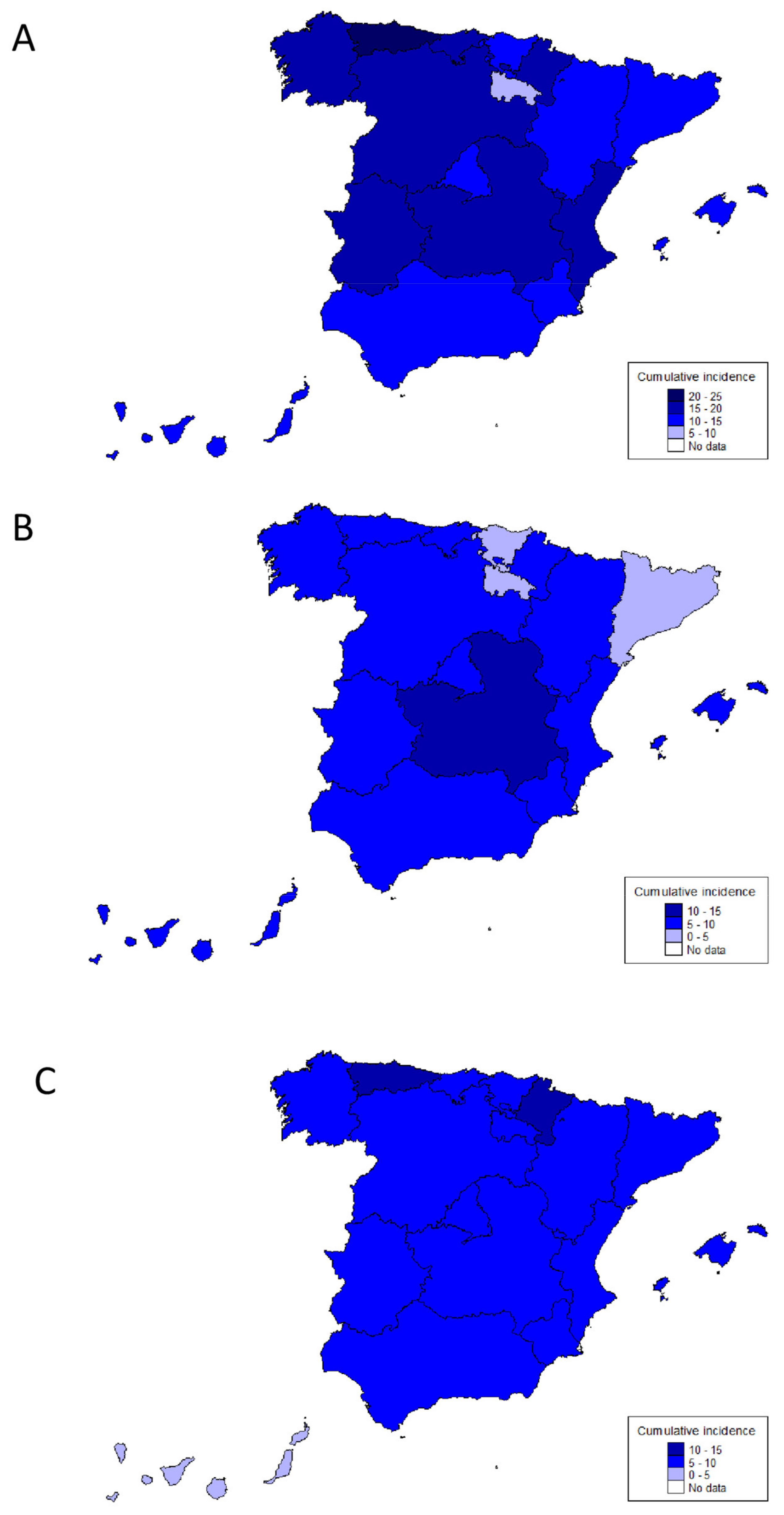

3.1. Incidence of IBD

3.2. Patients’ Characteristics

3.3. Drug Treatment and Surgery during the First 12 Months after Diagnosis

3.4. Hospitalizations

3.5. Drug Treatments, Surgery and Hospitalizations during the First 12 Months Based on Hospital Category

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

References

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Coward, S.; Clement, F.; Benchimol, E.I.; Bernstein, C.N.; Avina-Zubieta, J.A.; Bitton, A.; Carroll, M.W.; Hazlewood, G.; Jacobson, K.; Jelinski, S.; et al. Past and Future Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Based on Modeling of Population-Based Data. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Bemelman, W.; Bryant, R.V.; D’Haens, G.; Dotan, I.; Dubinsky, M.; Feagan, B.; et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targownik, L.E.; Kaplan, G.G.; Witt, J.; Bernstein, C.N.; Singh, H.; Tennakoon, A.; Zubieta, A.A.; Coward, S.B.; Jones, J.; Kuenzig, M.E.; et al. Longitudinal Trends in the Direct Costs and Health Care Utilization Ascribable to Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Biologic Era: Results From a Canadian Population-Based Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burisch, J.; Vardi, H.; Schwartz, D.; Friger, M.; Kiudelis, G.; Kupčinskas, J.; Fumery, M.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Lakatos, L.; Lakatos, P.L.; et al. Health-care costs of inflammatory bowel disease in a pan-European, community-based, inception cohort during 5 years of follow-up: A population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, S.; Tryggvason, F.; Jonasson, J.G.; Cariglia, N.; Orvar, K.; Kristjansdottir, S.; Stefansson, T. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Iceland 1995–2009. A nationwide population-based study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Kurti, Z.; Vegh, Z.; Golovics, P.A.; Fadgyas-Freyler, P.; Gecse, K.B.; Gonczi, L.; Gimesi-Orszagh, J.; Lovasz, B.D.; Lakatos, P.L. Nationwide prevalence and drug treatment practices of inflammatory bowel diseases in Hungary: A population-based study based on the National Health Insurance Fund database. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lophaven, S.N.; Lynge, E.; Burisch, J. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1980-2013: A nationwide cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S. Validity and bias in epidemiological research. In Oxford Textbook of Public Health, 5th ed.; Detels, R., Beaglehole, R., Lansang, M.A., Gulliford, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burisch, J.; Pedersen, N.; Cukovic-Cavka, S.; Brinar, M.; Kaimakliotis, I.; Duricova, D.; Shonová, O.; Vind, I.; Avnstrøm, S.; Thorsgaard, N.; et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: The ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut 2014, 63, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Acosta, M.B.-D.; Benítez, J.M.; Cabriada, J.L.; Casanova, M.J.; Ceballos, D.; Esteve, M.; Fernández, H.; Ginard, D.; Gomollón, F.; et al. EpidemIBD: Rationale and design of a large-scale epidemiological study of inflammatory bowel disease in Spain. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2019, 12, 1756284819847034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomollon, F.; Dignass, A.; Annese, V.; Tilg, H.; Van Assche, G.; Lindsay, J.O.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Cullen, G.J.; Daperno, M.; Kucharzik, T.; et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignass, A.; Eliakim, R.; Magro, F.; Maaser, C.; Chowers, Y.; Geboes, K.; Mantzaris, G.; Reinisch, W.; Colombel, J.-F.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis Part 1: Definitions and diagnosis (Spanish version). Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. 2014, 79, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Population resident in Spain. In National Institute of Statistics; 2017; Available online: www.ine.es (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Silverberg, M.S.; Satsangi, J.; Ahmad, T.; Arnott, I.D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Brant, S.R.; Caprilli, R.; Colombel, J.-F.; Gasche, C.; Geboes, K.; et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 19 (Suppl. A), 5A–36A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T.; Etchevers, M.J.; Merino, O.; Gallego, S.; Garcia-Sanchez, V.; Marin-Jimenez, I.; Menchén, L.; Acosta, M.B.; Bastida, G.; García, S.; et al. Does smoking influence Crohn’s disease in the biologic era? The TABACROHN study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegh, Z.; Burisch, J.; Pedersen, N.; Kaimakliotis, I.; Duricova, D.; Bortlik, M.; Avnstrøm, S.; Vinding, K.K.; Olsen, J.; Nielsen, K.R.; et al. Incidence and initial disease course of inflammatory bowel diseases in 2011 in Europe and Australia: Results of the 2011 ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantoro, L.; Di Sabatino, A.; Papi, C.; Margagnoni, G.; Ardizzone, S.; Giuffrida, P.; Giannarelli, D.; Massari, A.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Lenti, M.V.; et al. The Time Course of Diagnostic Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over the Last Sixty Years: An Italian Multicentre Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavricka, S.R.; Spigaglia, S.M.; Rogler, G.; Pittet, V.; Michetti, P.; Felley, C.; Mottet, C.; Braegger, C.P.; Rogler, D.; Straumann, A.; et al. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeuring, S.F.; van den Heuvel, T.R.; Liu, L.Y.; Zeegers, M.P.; Hameeteman, W.H.; Romberg-Camps, M.J.; Oostenbrug, L.E.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E.; Pierik, M.J. Improvements in the Long-Term Outcome of Crohn’s Disease Over the Past Two Decades and the Relation to Changes in Medical Management: Results from the Population-Based IBDSL Cohort. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Bressler, B.; Levesque, B.G.; Zou, G.; Stitt, L.W.; Greenberg, G.R.; Panaccione, R.; Bitton, A.; Paré, P.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Magro, F.; Caldeira, D.; Alarcao, J.; Sousa, R.; Vaz-Carneiro, A. Infliximab reduces hospitalizations and surgery interventions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burisch, J.; Kiudelis, G.; Kupcinskas, L.; Kievit, H.A.L.; Andersen, K.W.; Andersen, V.; Salupere, R.; Pedersen, N.; Kjeldsen, J.; D’Incà, R.; et al. Natural disease course of Crohn’s disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: An Epi-IBD study. Gut 2018, 68, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, J.; Katsanos, K.H.; Christodoulou, D.K.; Barros, L.; Magro, F.; Pedersen, N.; Kjeldsen, J.; Vegh, Z.; Lakatos, P.L.; Eriksson, C.; et al. Natural Disease Course of Ulcerative Colitis During the First Five Years of Follow-up in a European Population-based Inception Cohort-An Epi-IBD Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.A.; Underwood, F.E.; Panaccione, N.; Quan, J.; Windsor, J.W.; Kotze, P.G.; Ng, S.C.; Ghosh, S.; Lakatos, P.L.; Jess, T.; et al. Trends in hospitalisation rates for inflammatory bowel disease in western versus newly industrialised countries: A population-based study of countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Jairath, V.; Feagan, B.G.; Khanna, R.; Shariff, S.Z.; Allen, B.N.; Jenkyn, K.B.; Vinden, C.; Jeyarajah, J.; Mosli, M.; et al. Declining hospitalisation and surgical intervention rates in patients with Crohn’s disease: A population-based cohort. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall n = 3611 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 42 (30–55) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 1908 (53) |

| Former smokers, n (%) | 880 (24.5) |

| Symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | 3280 (92) |

| Diagnostic delay, months (median, IQR) | 3 (1–9) |

| Family history of IBD, n (%) | 524 (15) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary or none | 1220 (31) |

| Secondary | 1424 (41) |

| University degree | 961 (28) |

| Employment status | |

| Self-employed | 351 (10) |

| Employee | 1755 (51) |

| Unemployed | 532 (15.4) |

| Others | 326 (9.5) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 327 (9) |

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | 1647 (46) |

| Ileal, n (%) | 900 (55) |

| Colonic, n (%) | 312 (19) |

| Ileocolonic, n (%) | 431 (26) |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract, n (%) | 52 (3) |

| Inflammatory, n (%) | 1347 (82) |

| Stricturing, n (%) | 183 (11) |

| Fistulizing, n (%) | 114 (7) |

| Perianal, n (%) | 185 (11) |

| Ulcerative colitis, n (%) | 1807 (50) |

| Extensive, n (%) | 563 (31) |

| Left-sided colitis, n (%) | 563 (31) |

| Proctitis, n (%) | 678 (38) |

| Unclassified inflammatory bowel disease, n (%) | 156 (4) |

| Crohn’s Disease n = 1647 | Ulcerative Colitis n = 1807 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 41 (28–54) | 46 (34–57) | <0.05 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 821 (50) | 808 (45) | <0.05 |

| Former smokers, n (%) | 630 (38) | 217 (12) | <0.05 |

| Symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | 1465 (89.5) | 1675 (94) | <0.05 |

| Diagnostic delay, months (median, IQR) | 5 (1–15) | 2 (1–5) | <0.05 |

| Family history of IBD, n (%) | 288 (18) | 225 (13) | <0.05 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 204 (12) | 114 (6) | <0.05 |

| (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Patients | n = 3611 | ||

| Mesalamine, n (%) | 2450 (68) | ||

| Steroids, n (%) | 1916 (53) | ||

| Systemic steroid therapy, n (%) | 1252 (35) | ||

| Immunomodulators, n (%) | 936 (26) | ||

| Thiopurines, n (%) | 860 (24) | ||

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 114 (3.2) | ||

| Cyclosporine, n (%) | 13 (0.4) | ||

| Tofacitinib, n (%) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Biologics, n (%) | 558 (15.5) | ||

| Anti-TNF, n (%) | 535 (14.8) | ||

| Ustekinumab, n (%) | 24 (0.7) | ||

| Vedolizumab, n (%) | 34 (0.9) | ||

| Surgery, n (%) | 199 (5.5) | ||

| Hospital admissions, n (%) | 1012 (28) | ||

| (B) | |||

| Crohn’s Disease n = 1647 | Ulcerative Colitis n = 1807 | p | |

| Mesalamine ever, n (%) | 625 (38) | 1681 (73) | <0.01 |

| Steroids ever, n (%) | 1170 (71) | 688 (38) | <0.01 |

| Systemic steroid therapy, n (%) | 717 (43.5) | 497 (27.5) | <0.01 |

| Immunomodulators, n (%) | 746 (45) | 174 (10) | <0.01 |

| Biologics, n (%) | 415 (25) | 132 (7) | <0.01 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 174 (11) | 23 (1.3) | <0.01 |

| Hospital admissions, n (%) | 585 (35.5) | 391 (22) | <0.01 |

| Low Resources (Categories 1–2) n = 177 | High Resources (Categories 3–5) n = 3434 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 45 (31–55) | 43 (31–56) | >0.05 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 101 (57) | 1807 (53) | >0.05 |

| Never smokers, n (%) | 56 (32) | 1410 (41) | 0.01 |

| Symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | 166 (94.3) | 3114 (92) | >0.05 |

| Diagnostic delay, months (median, IQR) | 4 (1–15) | 3 (1–8) | >0.05 |

| Time from symptoms onset to primary care consultation, months (median, IQR) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (1–6) | >0.05 |

| Time from primary care to gastroenterologist consultation, months (median, IQR) | 1.5 (0–3) | 2 (0–5) | >0.05 |

| Family history of IBD, n (%) | 24 (14) | 501 (15) | >0.05 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 23 (13) | 304 (9) | >0.05 |

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | 88 (50) | 1559 (45.5) | >0.05 |

| Ileal, n (%) | 57 (65) | 843 (54) | >0.05 |

| Colonic, n (%) | 10 (11) | 302 (19.5) | >0.05 |

| Ileocolonic, n (%) | 21 (24) | 410 (26) | >0.05 |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract, n (%) | 1 (1) | 51 (3) | >0.05 |

| Inflammatory, n (%) | 76 (86) | 1271 (82) | >0.05 |

| Stricturing, n (%) | 9 (10) | 174 (11) | |

| Fistulizing, n (%) | 3 (4) | 111 (7) | |

| Perianal, n (%) | 4 (4.5) | 181 (11.7) | 0.04 |

| Ulcerative colitis, n (%) | 82 (46) | 1725 (50) | >0.05 |

| Extensive, n (%) | 25 (31) | 538 (31) | |

| Left-sided colitis, n (%) | 24 (29) | 539 (31) | >0.05 |

| Proctitis, n (%) | 33 (40) | 645 (38) | |

| Unclassified inflammatory bowel disease, n (%) | 7 (4) | 149 (4.5) | >0.05 |

| Low Resources (Categories 1–2) n = 177 | High Resources (Categories 3–5) n = 3434 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalamine ever, n (%) | 136 (77) | 2314 (67.4) | <0.01 |

| Steroids ever, n (%) | 102 (58) | 1814 (53) | >0.05 |

| Systemic steroid therapy, n (%) | 53 (30) | 1199 (35) | >0.05 |

| Immunomodulators, n (%) | 56 (32) | 880 (26) | >0.05 |

| Biologics, n (%) | 22 (12) | 536 (16) | >0.05 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 8 (4.5) | 191 (5.6) | >0.05 |

| Hospital admissions, n (%) | 39 (22) | 973 (28) | >0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaparro, M.; Garre, A.; Núñez Ortiz, A.; Diz-Lois Palomares, M.T.; Rodríguez, C.; Riestra, S.; Vela, M.; Benítez, J.M.; Fernández Salgado, E.; Sánchez Rodríguez, E.; et al. Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132885

Chaparro M, Garre A, Núñez Ortiz A, Diz-Lois Palomares MT, Rodríguez C, Riestra S, Vela M, Benítez JM, Fernández Salgado E, Sánchez Rodríguez E, et al. Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(13):2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132885

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaparro, María, Ana Garre, Andrea Núñez Ortiz, María Teresa Diz-Lois Palomares, Cristina Rodríguez, Sabino Riestra, Milagros Vela, José Manuel Benítez, Estela Fernández Salgado, Eugenia Sánchez Rodríguez, and et al. 2021. "Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 13: 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132885

APA StyleChaparro, M., Garre, A., Núñez Ortiz, A., Diz-Lois Palomares, M. T., Rodríguez, C., Riestra, S., Vela, M., Benítez, J. M., Fernández Salgado, E., Sánchez Rodríguez, E., Hernández, V., Ferreiro-Iglesias, R., Ponferrada Díaz, Á., Barrio, J., Huguet, J. M., Sicilia, B., Martín-Arranz, M. D., Calvet, X., Ginard, D., ... on behalf of the EpidemIBD study group of GETECCU. (2021). Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(13), 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132885