Are Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Two Sides of the Same Coin, to Grade Recommendations for Drug Approval?

Abstract

1. How to Measure the Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials

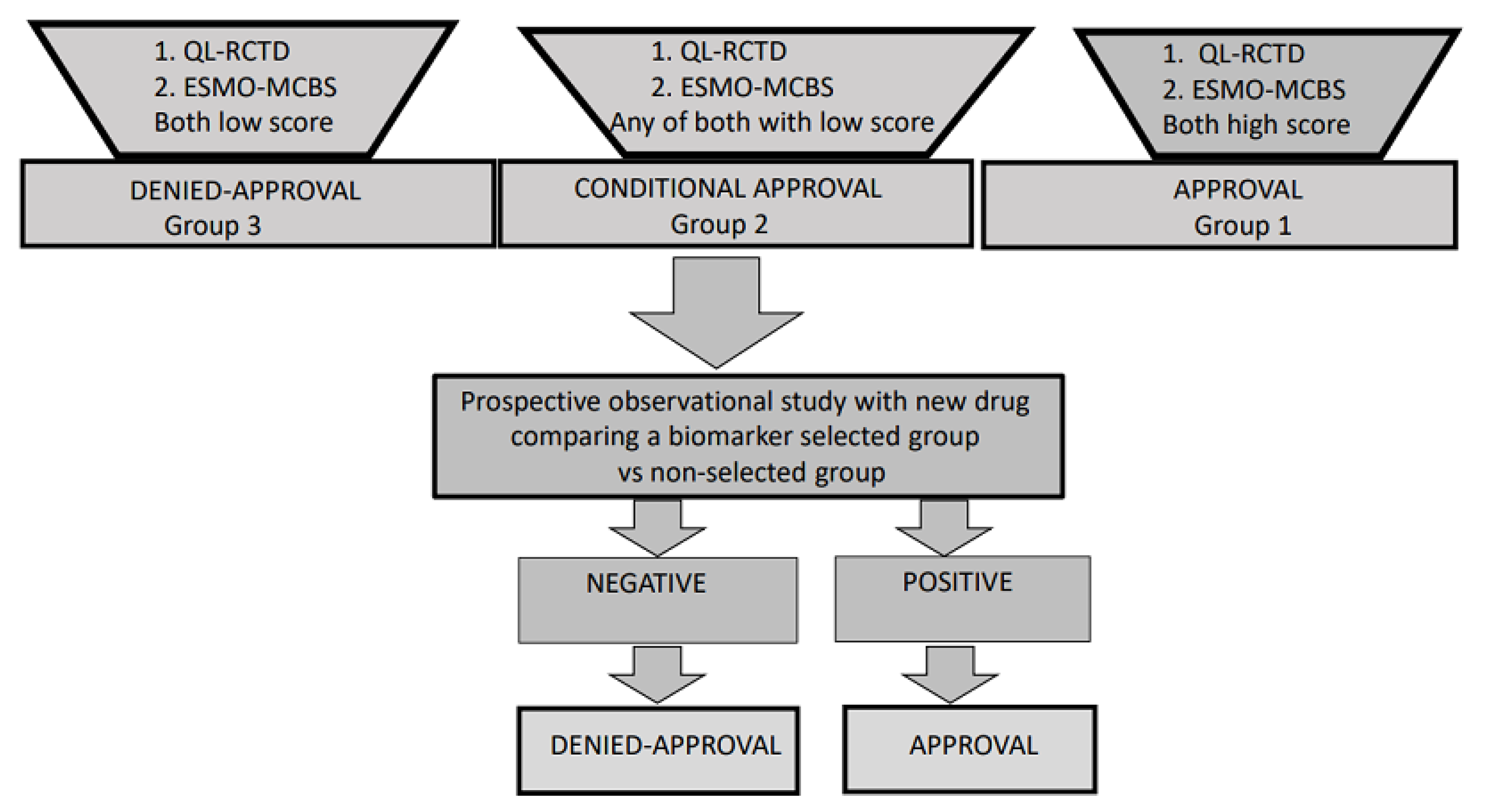

1.1. Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. Is It Time to Change?

1.2. Progression-Free Survival Is a Vulnerable Endpoint

1.3. Concordance between PFS and OS as a Measure of Quality of Clinical Trial Design (QCTD)

2. How to Evaluate Clinical Benefit?

2.1. The European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS)

2.2. ASCO Value Framework for Assessing Value in Cancer Care

2.3. Concordance between ASCO-VF-NHB16 and ESMO-MCBS

2.4. ASCO-VF and ESMO-MCBS as a Tool to Evaluate Medical Agency Approvals

3. Final Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkins, D.; Best, D.; Briss, P.; Eccles, M.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Flottorp, S. Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2004, 328, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, P.R.; Forner, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Mazzaferro, V.; Piscaglia, F.; Raoul, J.L.; Schirmacher, P.; Vilgrain, V. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Sobrero, A.; Van Krieken, J.H.; Aderka, D.; Aguilar, E.A.; Bardelli, A.; Benson, A.; Bodoky, G.; et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1386–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykewicz, C.A. Summary of the Guidelines for Preventing Opportunistic Infections among Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Per-Protocol Analyses of Pragmatic Trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Addendum on Estimands and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials to the Guideline on Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials E9(R1). In Federal Register; International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt, C.H.; Bell, J.; Liu, G.; Ratitch, B.; O’Kelly, M.; Lipkovich, I.; Singh, P.; Xu, L.; Molenberghs, G. Aligning Estimators with Estimands in Clinical Trials: Putting the ICH E9(R1) Guidelines into Practice. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, C.; Blanke, C.; Buyse, M.; Goldberg, R.; Grothey, A.; Meropol, N.J.; Saltz, L.; Venook, A.; Yothers, G.; Sargent, D. End Points in Advanced Colon Cancer Clinical Trials: A Review and Proposal. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 3572–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, V.; Kim, C.; Burotto, M.; Vandross, A. The Strength of Association between Surrogate End Points and Survival in Oncology: A Systematic Review of Trial-Level Meta-Analyses. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, M.J.; Robinson, A.; Booth, C.M.; O’Donnell, J.; Palmer, M.; Eisenhauer, E.; Brundage, M. The Value of Progression-Free Survival as a Treatment End Point among Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Assessment of the Literature. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Albéniz, X.; Maurel, J.; Hernán, M.A. Why post-progression survival and post-relapse survival are not appropriate measures of efficacy in cancer randomized clinical trials. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 2444–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; De Gramont, A.; Grothey, A.; Zalcberg, J.; Chibaudel, B.; Schmoll, H.J.; Seymour, M.T.; Adams, R.; Saltz, L.; Goldberg, R.M.; et al. Individual Patient Data Analysis of Progression-Free Survival versus Overall Survival as a First-Line End Point for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in Modern Randomized Trials: Findings from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System Databa. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderka, D.; Stintzing, S.; Heinemann, V. Explaining the unexplainable: Discrepancies in results from the CALGB/SWOG 80405 and FIRE-3 studies. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e274–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.A.; Bentzen, S.M.; Chen, E.X.; Siu, L.L. Surrogate End Points for Median Overall Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Literature-Based Analysis From 39 Randomized Controlled Trials of First-Line Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4562–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyse, M.; Burzykowski, T.; Carroll, K.; Michiels, S.; Sargent, D.J.; Miller, L.L.; Elfring, G.L.; Pignon, J.P.; Piedbois, P. Progression-Free Survival Is a Surrogate for Survival in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5218–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giessen, C.; Laubender, R.P.; Ankerst, D.P.; Stintzing, S.; Modest, D.P.; Mansmann, U.; Heinemann, V. Progression-Free Survival as a Surrogate Endpoint for Median Overall Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Literature-Based Analysis from 50 Randomized First-Line Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidhu, R.; Rong, A.; Dahlberg, S. Evaluation of Progression-Free Survival as a Surrogate Endpoint for Survival in Chemotherapy and Targeted Agent Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrell, F.; Barni, S. Correlation of Progression-Free and Post-Progression Survival with Overall Survival in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechartres, A.; Tan, A.; Porcher, R.; Crequit, P.; Ravaud, P. Differences in Treatment Effect Size between Overall Survival and Progression-Free Survival in Immunotherapy Trials: A Meta-Epidemiologic Study of Trials with Results Posted at ClinicalTrials.Gov. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Novotny, W.; Cartwright, T.; Hainsworth, J.; Heim, W.; Berlin, J.; Baron, A.; Griffing, S.; Holmgren, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus Irinotecan, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltz, L.B.; Clarke, S.; Díaz-Rubio, E.; Scheithauer, W.; Figer, A.; Wong, R.; Koski, S.; Lichinitser, M.; Yang, T.S.; Rivera, F.; et al. Bevacizumab in Combination with Oxaliplatin-Based Chemotherapy as First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, N.; Lin, L.Z.; Wu, Q.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of First-Line Cetuximab plus Leucovorin, Fluorouracil, and Oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) versus FOLFOX-4 in Patientswith RASwild-Typemetastatic Colorectal Cancer: The Open-Label, Randomized, Phase III TAILOR Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3031–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokemeyer, C.; Bondarenko, I.; Hartmann, J.T.; de Braud, F.; Schuch, G.; Zubel, A.; Celik, I.; Schlichting, M.; Koralewski, P. Efficacy According to Biomarker Status of Cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 as First-Line Treatment for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The OPUS Study. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Lenz, H.J.; Köhne, C.H.; Heinemann, V.; Tejpar, S.; Melezínek, I.; Beier, F.; Stroh, C.; Rougier, P.; Han Van Krieken, J.; et al. Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Irinotecan plus Cetuximab Treatment and RAS Mutations in Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douillard, J.-Y.; Siena, S.; Cassidy, J.; Tabernero, J.; Burkes, R.; Barugel, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bodoky, G.; Cunningham, D.; Jassem, J.; et al. Randomized, Phase III Trial of Panitumumab with Infusional Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) Versus FOLFOX4 Alone as First-Line Treatment in Patients with Previously Untreated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The PRIME Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4697–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.-Z.; Xu, J.-M.; Luo, R.-C.; Feng, F.-Y.; Wang, L.-W.; Shen, L.; Yu, S.-Y.; Ba, Y.; Liang, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in Chinese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III ARTIST trial. Chin. J. Cancer 2011, 30, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebbutt, N.C.; Wilson, K.; Gebski, V.J.; Cummins, M.M.; Zannino, D.; Van Hazel, G.A.; Robinson, B.; Broad, A.; Ganju, V.; Ackland, S.P.; et al. Capecitabine, Bevacizumab, and Mitomycin in First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Results of the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Randomized Phase III MAX Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passardi, A.; Nanni, O.; Tassinari, D.; Turci, D.; Cavanna, L.; Fontana, A.; Ruscelli, S.; Mucciarini, C.; Lorusso, V.; Ragazzini, A.; et al. Effectiveness of bevacizumab added to standard chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: Final results for first-line treatment from the ITACa randomized clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Köhne, C.-H.; Hitre, E.; Zaluski, J.; Chang Chien, C.-R.; Makhson, A.; D’Haens, G.; Pintér, T.; Lim, R.; Bodoky, G.; et al. Cetuximab and Chemotherapy as Initial Treatment for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douillard, J.-Y.; Oliner, K.S.; Siena, S.; Tabernero, J.; Burkes, R.; Barugel, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bodoky, G.; Cunningham, D.; Jassem, J.; et al. Panitumumab–FOLFOX4 Treatment and RAS Mutations in Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, T.S.; Adams, R.; Smith, C.G.; Meade, A.M.; Seymour, M.T.; Wilson, R.H.; Idziaszczyk, S.; Harris, R.; Fisher, D.; Kenny, S.L.; et al. Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: Results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokemeyer, C.; Köhne, C.-H.; Ciardiello, F.; Lenz, H.-J.; Heinemann, V.; Klinkhardt, U.; Beier, F.; Duecker, K.; Van Krieken, J.; Tejpar, S. FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tveit, K.M.; Guren, T.; Glimelius, B.; Pfeiffer, P.; Sorbye, H.; Pyrhonen, S.; Sigurdsson, F.; Kure, E.; Ikdahl, T.; Skovlund, E.; et al. Phase III Trial of Cetuximab With Continuous or Intermittent Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Oxaliplatin (Nordic FLOX) Versus FLOX Alone in First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The NORDIC-VII Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; Sullivan, R.; Dafni, U.; Kerst, J.M.; Sobrero, A.; Zielinski, C.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Piccart, M.J. A Standardised, Generic, Validated Approach to Stratify the Magnitude of Clinical Benefit That Can Be Anticipated from Anti-Cancer Therapies. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 28, 2901–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Dafni, U.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; McKernin, S.E.; Piccart, M.; Latino, N.J.; Douillard, J.Y.; Schnipper, L.E.; Somerfield, M.R.; et al. Comparative Assessment of Clinical Benefit Using the ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Version 1.1 and the ASCO Value Framework Net Health Benefit Score. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnipper, L.E.; Davidson, N.E.; Wollins, D.S.; Blayney, D.W.; Dicker, A.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Hoverman, J.R.; Langdon, R.; Lyman, G.H.; Meropol, N.J.; et al. Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework: Revisions and Reflections in Response to Comments Received. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Paggio, J.C.; Sullivan, R.; Schrag, D.; Hopman, W.M.; Azariah, B.; Pramesh, C.S.; Tannock, I.F.; Booth, C.M. Delivery of meaningful cancer care: A retrospective cohort study assessing cost and benefit with the ASCO and ESMO frameworks. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Paggio, J.C.; Azariah, B.; Sullivan, R.; Hopman, W.M.; James, F.V.; Roshni, S.; Tannock, I.F.; Booth, C.M. Do Contemporary Randomized Controlled Trials Meet ESMO Thresholds for Meaningful Clinical Benefit? Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; McDonald, E.J.; Cheung, M.C.; Arciero, V.S.; Qureshi, M.; Jiang, D.; Ezeife, D.; Sabharwal, M.; Chambers, A.; Han, D.; et al. Do the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework and the European Society of Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Measure the Same Construct of Clinical Benefit? J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; Dafni, U.; Bogaerts, J.; Latino, N.J.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Douillard, J.Y.; Tabernero, J.; Zielinski, C.; Piccart, M.J.; de Vries, E.G.E. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Version 1.1. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2340–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Paggio, J.C.; Cheng, S.; Booth, C.M.; Cheung, M.C.; Chan, K.K.W. Reliability of Oncology Value Framework Outputs: Concordance Between Independent Research Groups. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018, 2, pky050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, L.; Shah, M.; Chan, K.K.W. Comparison of Long-term Survival Benefits in Trials of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor vs Non-Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Anticancer Agents Using ASCO Value Framework and ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saluja, R.; Everest, L.; Cheng, S.; Cheung, M.; Chan, K.K.W. Assessment of Whether the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value Framework and the European Society for Medical Oncology’s Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Measure Absolute or Relative Clinical Survival Benefit: An Analysis of Randomized Clinica. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 16, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivot, A.; Jacot, J.; Zeitoun, J.-D.; Ravaud, P.; Crequit, P.; Porcher, R. Clinical benefit, price and approval characteristics of FDA-approved new drugs for treating advanced solid cancer, 2000–2015. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibau, A.; Molto, C.; Ocana, A.; Templeton, A.J.; Del Carpio, L.P.; Del Paggio, J.C.; Barnadas, A.; Booth, C.M.; Amir, E. Magnitude of Clinical Benefit of Cancer Drugs Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grössmann, N.; Del Paggio, J.; Wolf, S.; Sullivan, R.; Booth, C.; Rosian, K.; Emprechtinger, R.; Wild, C. Five years of EMA-approved systemic cancer therapies for solid tumours—a comparison of two thresholds for meaningful clinical benefit. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 82, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.-A.; Wright, G.S.; et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 29, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, D.; Andre, F.; Gligorov, J.; Verma, S.; Xu, B.; Cameron, D.; Barrios, C.; Schneeweiss, A.; Easton, V.; Dolado, I.; et al. IMpassion131: Phase III study comparing 1L atezolizumab with paclitaxel vs placebo with paclitaxel in treatment-naive patients with inoperable locally advanced or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC). Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, v105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. KEYNOTE-355: Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Study of Pembrolizumab + Chemotherapy versus Placebo + Chemotherapy for Previously Untreated Locally Recurrent Inoperable or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Moehler, M.H.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Adenis, A.; Aucoin, J.-S.; Boku, N.; Chau, I.; Cleary, J.M.; Feeney, K.; Franke, F.A.; Mendez, G.A.; et al. CheckMate 649: A randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) + ipilimumab (IPI) or nivo + chemotherapy (CTX) versus CTX alone in patients with previously untreated advanced (Adv) gastric (G) or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, TPS192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boku, N.; Ryu, M.-H.; Kato, K.; Chung, H.; Minashi, K.; Lee, K.-W.; Cho, H.; Kang, W.; Komatsu, Y.; Tsuda, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in combination with S-1/capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, advanced, or recurrent gastric/gastroesophageal junction cancer: Interim results of a randomized, phase II trial (ATTRACTION-4). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Shah, M.; Enzinger, P.; Bennouna, J.; Shen, L.; Adenis, A.; Sun, J.-M.; Cho, B.C.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Kojima, T.; et al. KEYNOTE-590: Phase III study of first-line chemotherapy with or without pembrolizumab for advanced esophageal cancer. Futur. Oncol. 2019, 15, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitara, K.; Van Cutsem, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Fuchs, C.; Wyrwicz, L.; Lee, K.W.; Kudaba, I.; Garrido, M.; Chung, H.C.; Lee, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab or Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy vs Chemotherapy Alone for Patients with First-Line, Advanced Gastric Cancer: The KEYNOTE-062 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | No Trials | Tumor Type | Type of Therapy | Slope Regression Line | rHR | STE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang [15] | 39 | mCRC | CHT | 0.54 | - | |

| Buyse [16] | 10 | mCRC | CHT | 0.81 | - | 0.77 |

| Giessen [17] | 50 | mCRC | CHT and TA | - | - | |

| Sidhu [18] | 24 | mCRC | CHT and TA | 0.58 (all) 0.64 (FL) | 0.72 to 0.91 (anti-EGFR, WT KRAS subgroup to First Line) | |

| Shi [13] | 22 | mCRC | CHT and TA | - | - | 0.57 |

| Petrell [19] | 34 | mCRC | CHT and TA | 1.34 | - | |

| Tan [20] | 51 | Across tumor type | TA | - | 0.83 (0.79–0.88) | 0.50 |

| Author | n Patients | Treatment Arm | PFS (C vs. E) | OS (C vs. E) | SRL | rHR | HRPFS | HROS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurwitz [21] | 814 | IFL +/− BEV | 6.2 vs. 10.6 | 15.6 vs. 20.3 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.66 |

| Saltz [22] | 1401 | FOLFOX/CAPOX +/− BEV | 8 vs. 9.4 | 19.9 vs. 21.3 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

| Guan [27] | 214 | IFL +/− BEV | 4.2 vs. 8.3 | 13.4 vs. 18.7 | 1.28 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.62 |

| Tebbutt [28] | 313 | CAP +/− BEV | 5.7 vs. 8.5 | 18.9 vs. 16.4 | <0.5 | 0.61 | 0.624 | 0.875 |

| Passardi [29] | 376 | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI +/− BEV | 8.4 vs. 9.6 | 21.3 vs. 20.8 | <0.5 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 1.13 |

| Van Cutsem [25] | 1198 | FOLFIRI +/− CET | 8 vs. 8.9 | 18.6 vs. 19.9 | 1.44 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 0.93 |

| Douillard [26] | 656 | FOLFOX +/− PAN | 8 vs. 9.6 | 19.7 vs. 23.9 | 2.6 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Maughan [32] | 729 | CAPOX +/− CET | 8.6 vs. 8.6 | 17.9 vs. 17 | <0.5 | 1.1 | 1.04 | 0.96 |

| Bokemeyer [24] | 337 | FOLFOX +/− CET | 7.2 vs. 7.2 | 18 vs. 18.3 | <0.5 | 0.92 | 0.931 | 1.015 |

| Tveit [34] | 566 | FLOX +/− CET | 7.9 vs. 8.3 | 20.4 vs. 19.7 | <0.5 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 1.06 |

| Qin [23] | 393 | FOLFOX +/− CET | 7.4 vs. 9.2 | 17.8 vs. 20.7 | 1.6 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| Bokemeyer [33] * | 87 | FOLFOX +/− CET | 5.8 vs. 12 | 17.8 vs. 19.8 | <0.5 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.94 |

| Van Cutsem [30] * | 367 | FOLFIRI +/− CET | 8.4 vs. 11.4 | 20.2 vs. 28.4 | 2.7 | 0.81 | 0.56 | 0.69 |

| Douillard [31] * | 512 | FOLFOX +/− PAN | 7.9 vs. 10.1 | 20.2 vs. 25.8 | 2.6 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| Author | No RCTs | Type of Therapy | ESMO-MCBS Benefit% * | ASCO-VF Benefit% * | EMA | FDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Del Paggio [39] | 277 | CYT, TA, IT, HT | 31 | NE | NE | NE |

| Vivot [45] | 51 | CYT, TA, IT, HT | 25 | 34 | NE | FDA approval |

| Tibau [46] | 105 | CYT, TA, IT, HT | 38.8 ** | NE | NE | FDA approval |

| Grössmann [47] | 70 | ND | 11 *** | NE | EMA approval | NE |

| Type of Analysis | Pitfalls | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| A | 1. Missing information of critical prognostic variables at the time of tumor progression | 1. Identify in the control and experimental arms critical important variables basally and at the time of tumor progression |

| A | 2. Use inadequate control arm | 2. Select adequate control arms |

| A | 3. Modify primary endpoint or use multiple primary endpoints | 3. Maintain primary endpoint and use OS as a primary endpoint with an intention to treat analysis |

| A | 4. Plan subgroup analysis as a primary endpoint | 4. Plan subgroup analysis as a secondary endpoint mainly to generate a hypothesis |

| A | 5. Miss clear definition of censored patients in the protocol and numbers in the final report | 5. Clarify the definition of censored patients in all situations. Specified in the analysis the% of censored patients and the reasons. |

| A | 6. Not evaluate the r (HRPFS/HROS) | 6. Evaluate the r and recommend specifically studies that the r range between 0.75 and 0.9 |

| A | 7. Not evaluate the slope of the curve between PFS and OS | 7. Evaluate the slope of the curve between PFS and OS and recommend specifically studies that the slope of the curve range between 0.5 and 0.8 |

| B | 8. Consider the inferior limit of 95% CI of H for OS (between 0.70 and 0.75) as an adequate endpoint for ESMO-MCBS punctuation in subgroup analysis | 8. If subgroup analysis were done, H estimate (between 0.70 and 0.75) instead of the inferior limit of 95% CI would be recommended to assess ESMO-MCBS |

| B | 9. Not consider the 3 points (% of patients with OS at 2–3–5 years, improvement in H* and median OS) to evaluate the MCBS and do not take the upper punctuation (grade 4 only for OS) to drive positive recommendations for FDA or EMA approvals | 9. Consider all 3 points in the MBSC evaluation and take the upper punctuation* (grade 4 only for OS) to drive positive recommendations for FDA or EMA approvals |

| Trial | No. Patient | Treatment Arms | QRCT1 Control Arm | QRCT1 Primary Endpoint * | QRCT1 Endpoint ** | QRCT2 SRL | QRCT2 r | ESMO-MCBS PFS | ESMO-MCBS OS | Modified ESMO-MCBS OS *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNBC | ||||||||||

| IMpassion 130 [48] | 902 | Nab-P + atezolizumab vs. Nab-P | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 | 0.91 | 1 | 2 | |

| CPS > 10% | 369 (41%) | 3 | 0.92 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| IMpassion 131 [49] | 651 | P + atezolizumab vs. P | 1 | 0 | 0 | <0.5 | 0.78 | 1 | 1 | |

| CPS > 1% | 292 (44%) | <0.5 | 073 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| KEYNOTE-355 [50] | 847 | CG/P/Nab-P + pembrolizumab vs. CG/P/Nab-P | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA |

| CPS > 10% | 323 (38%) | NA | NA | 3 | NA | NA | ||||

| EC/GEJ/G | ||||||||||

| CHECKMATE 649 [51] | 1581 | FOLFOX/CAPOX + nivolumab vs. FOLFOX/CAPOX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 0.85 | 1 | 2 | |

| CPS > 5% | 955 (60%) | 2.1 | 0.96 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| ATTRACTION-4 [52] | 724 | CAPOX + nivolumab vs. CAPOX | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 2 | 1 | |

| KEYNOTE-590 [53] | 749 | CP/FU + pembrolizumab vs. CP/FU# | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5.2 | 0.89 | 1 | 3 | |

| CPS > 10% | 383 (51%) | 2.05 | 0.82 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| KEYNOTE-062 [54](CPS > 1%) | 507 **** | CP/FU + pembrolizumab vs. CP/FU vs. pembrolizumab | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2.8 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez, A.; Esposito, F.; Oliveres, H.; Torres, F.; Maurel, J. Are Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Two Sides of the Same Coin, to Grade Recommendations for Drug Approval? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040746

Rodriguez A, Esposito F, Oliveres H, Torres F, Maurel J. Are Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Two Sides of the Same Coin, to Grade Recommendations for Drug Approval? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(4):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040746

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez, Adela, Francis Esposito, Helena Oliveres, Ferran Torres, and Joan Maurel. 2021. "Are Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Two Sides of the Same Coin, to Grade Recommendations for Drug Approval?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 4: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040746

APA StyleRodriguez, A., Esposito, F., Oliveres, H., Torres, F., & Maurel, J. (2021). Are Quality of Randomized Clinical Trials and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Two Sides of the Same Coin, to Grade Recommendations for Drug Approval? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(4), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040746