Systemic Catecholaminergic Deficiency in Depressed Patients with and without Coronary Artery Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Analyses

2.4. Psychometry

2.4.1. Assessment of Depression

2.4.2. Assessment of Anxiety, Stress and Physical Symptoms

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Subjects’ Characteristics

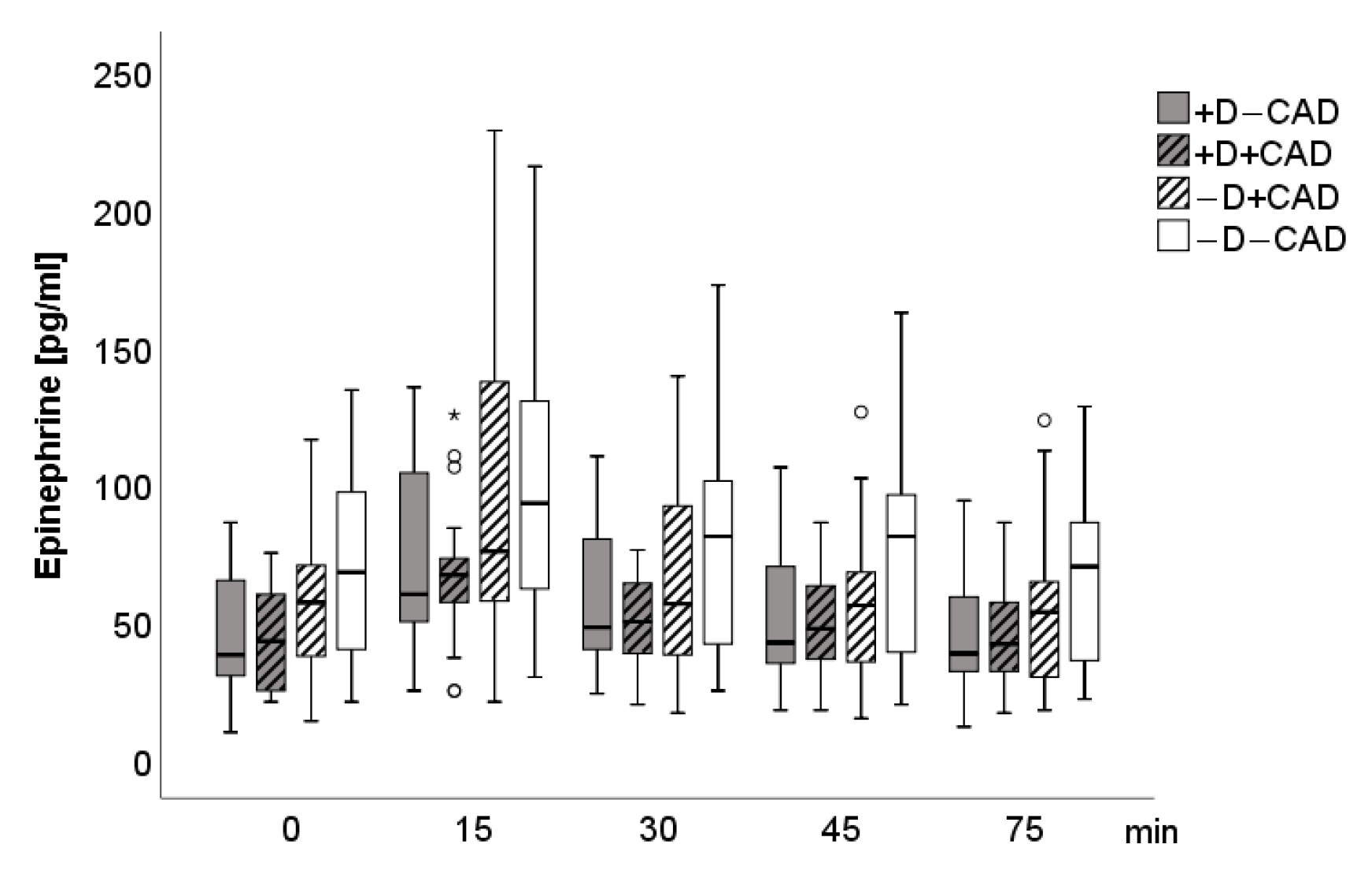

3.2. SAM-Axis at Baseline and during Stress Response

3.3. SAM-Axis and Inflammatory Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leung, Y.W.; Flora, D.B.; Gravely, S.; Irvine, J.; Carney, R.M.; Grace, S.L. The Impact of Premorbid and Postmorbid Depression Onset on Mortality and Cardiac Morbidity among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-Analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2012, 74, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amare, A.T.; Schubert, K.O.; Tekola-Ayele, F.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Sangkuhl, K.; Jenkins, G.; Whaley, R.M.; Barman, P.; Batzler, A.; Altman, R.B.; et al. The association of obesity and coronary artery disease genes with response to SSRIs treatment in major depression. J. Neural. Transm. 1996, 126, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akosile, W.; Voisey, J.; Lawford, B.; ColquhounC, D.; Young, R.M.; Mehta, D. The inflammasome NLRP12 is associated with both depression and coronary artery disease in Vietnam veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huffman, J.C.; Celano, C.M.; Beach, S.R.; Motiwala, S.R.; Januzzi, J.L. Depression and Cardiac Disease: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Diagnosis. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2013, 2013, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lichtman, A.H.; Binder, C.J.; Tsimikas, S.; Witztum, J.L. Adaptive immunity in atherogenesis: New insights and therapeutic approaches. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridker, P.M.; Danielson, E.; Fonseca, F.A.; Genest, J.; Gotto, A.M., Jr.; Kastelein, J.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, K.H.; Ryu, J.; Hong, K.H.; Ko, J.; Pak, Y.K.; Kim, J.-B.; Park, S.W.; Kim, J.J. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibition Reduces Monocyte CC Chemokine Receptor 2 Expression and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1–Mediated Monocyte Recruitment In Vivo. Circulation 2005, 111, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, H.-L.; Ueng, K.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-S.; Chiang, W.-L.; Yang, S.-F.; Chu, S.-C. Impact of MCP-1 and CCR-2 gene polymorphisms on coronary artery disease susceptibility. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 9023–9030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, I.; Abegunewardene, N.; Seul, M.; Vosseler, M.; Horstick, G.; Buerke, M.; Darius, H.; Lindemann, S. Elevated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 serum levels in patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2005, 69, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelken, N.A.; Coughlin, S.R.; Gordon, D.; Wilcox, J.N. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human atheromatous plaques. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eriksson, E.E. Mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment to atherosclerotic lesions: Future prospects. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2004, 15, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, C.; Radermacher, P.; Wepler, M.; Nußbaum, B. Non-Hemodynamic Effects of Catecholamines. Shock Inj. Inflamm. Sepsis Lab. Clin. Approaches 2017, 48, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schömig, A. Catecholamines in myocardial ischemia. Systemic and cardiac release. Circulation 1990, 82, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Tang, C.; Yang, Y. Psychological stress, immune response, and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2012, 223, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petidis, K.; Douma, S.; Doumas, M.; Basagiannis, I.; Vogiatzis, K.; Zamboulis, C. The interaction of vasoactive substances during exercise modulates platelet aggregation in hypertension and coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2008, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wessel, J.; Moratorio, G.; Rao, F.; Mahata, M.; Zhang, L.; Greene, W.; Rana, B.K.; Kennedy, B.P.; Khandrika, S.; Huang, P.; et al. C-reactive protein, an “intermediate phenotype” for inflammation: Human twin studies reveal heritability, association with blood pressure and the metabolic syndrome, and the influence of common polymorphism at catecholaminergic/beta-adrenergic pathway loci. J. Hypertens. 2007, 25, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.; Gruenewald, T.; Karlamangla, A.; Sidney, S.; Liu, K.; McEwen, B.; Schwartz, J. Modeling multisystem biological risk in young adults: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2009, 22, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulleryd, M.A.; Prahl, U.; Börsbo, J.; Schmidt, C.; Nilsson, S.; Bergström, G.; Johansson, M.E. The association between autonomic dysfunction, inflammation and atherosclerosis in men under investigation for carotid plaques. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pagano, G.; Talamanca, A.A.; Castello, G.; Cordero, M.D.; d’Ischia, M.; Gadaleta, M.N.; Pallardó, F.V.; Pertović, S.; Tiano, L.; Zatterale, A. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction across broad-ranging pathologies: Toward mitochondria-targeted clinical strategies. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 541230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonhajzerova, I.; Sekaninova, N.; Olexova, L.B.; Visnovcova, Z. Novel Insight into Neuroimmune Regulatory Mechanisms and Biomarkers Linking Major Depression and Vascular Diseases: The Dilemma Continues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Köhler, C.A.; Freitas, T.H.; Maes, M.; De Andrade, N.Q.; Liu, C.S.; Fernandes, B.S.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Herrmann, N.; et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopschina Feltes, P.; Doorduin, J.; Klein, H.C.; Juárez-Orozco, L.E.; Dierckx, R.A.; Moriguchi-Jeckel, C.M.; de Vries, E.F. Anti-inflammatory treatment for major depressive disorder: Implications for patients with an elevated immune profile and non-responders to standard antidepressant therapy. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valkanova, V.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Allan, C.L. CRP, IL-6 and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Affect Disord. 2013, 150, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswarappa, M.; Neylan, T.C.; Whooley, M.A.; Metzler, T.J.; Cohen, B.E. Inflammation as a predictor of disease course in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: A prospective analysis from the Mind Your Heart Study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 75, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Bin Wei, Y.; Strawbridge, R.; Bao, Y.; Chang, S.; Shi, L.; Que, J.; Gadad, B.S.; Trivedi, M.H.; Kelsoe, J.R.; et al. Peripheral cytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 25, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lindqvist, D.; Dhabhar, F.S.; James, S.J.; Hough, C.M.; Jain, F.A.; Bersani, F.S.; Reus, V.I.; Verhoeven, J.E.; Epel, E.S.; Mahan, L.; et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation and treatment response in major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 76, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manikowska, K.; Mikołajczyk, M.; Mikołajczak, P.Ł.; Bobkiewicz-Kozłowska, T. The influence of mianserin on TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 serum levels in rats under chronic mild stress. Pharmacol. Rep. 2014, 66, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Han, J.W.; Jeong, H.-G.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, S.B.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.W. Parasympathetic predominance is a risk factor for future depression: A prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngampramuan, S.; Tungtong, P.; Mukda, S.; Jariyavilas, A.; Sakulisariyaporn, C. Evaluation of Autonomic Nervous System, Saliva Cortisol Levels, and Cognitive Function in Major Depressive Disorder Patients. Depress. Res. Treat 2018, 2018, 7343592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linnoila, M.; Karoum, F.; Calil, H.M.; Kopin, I.J.; Potter, W.Z. Alteration of Norepinephrine Metabolism with Desipramine and Zimelidine in Depressed Patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1982, 39, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Pickar, D.; Linnoila, M.; Potter, W.Z. Plasma Norepinephrine Level in Affective Disorders: Relationship to Melancholia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1985, 42, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehi, A.; Mangano, D.; Pipkin, S.; Browner, W.S.; Whooley, M.A. Depression and heart rate variability in patients with stable coronary heart disease: Findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorman, J.M.; Sloan, R.P. Heart rate variability in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am. Heart J. 2000, 140, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rovere, M.T.; Bigger, J.T.; Marcus, F.I.; Mortara, A.; Schwartz, P.J. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes after Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet 1998, 351, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. Autonomic nervous system and neuroimmune interactions: New insights and clinical implications. Neurology 2019, 92, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Qin, P.; Yang, X. Comorbidity between depression and asthma via immune-inflammatory pathways: A meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 2014, 166, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperner-Unterweger, B.; Kohl, C.; Fuchs, D. Immune changes and neurotransmitters: Possible interactions in depression? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, L.; Glanzmann, P.; Schaffner, C.D.; Spielberger, C.D. Das State-Trait-Angstinventar (Testmappe Mit Handanweisung, Fragebogen STAI-G Form X 1 Und Fragebogen STAI-G Form X 2); Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gaab, J. PASA—Primary Appraisal Secondary Appraisal. Verhaltenstherapie 2009, 19, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zerssen, D.v.; Petermann, F. B-LR—Beschwerden-Liste—Revidierte Fassung; Hogrefe Testzentrale: Göttingen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.-M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’—A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breier, A.; Albus, M.; Pickar, D.; Zahn, T.P.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Paul, S.M. Controllable and uncontrollable stress in humans: Alterations in mood and neuroendocrine and psychophysiological function. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lechin, F.; Van Der Dijs, B.; Benaim, M. Stress versus depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 20, 899–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucolo, C.; Leggio, G.M.; Drago, F.; Salomone, S. Dopamine outside the brain: The eye, cardiovascular system and endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 203, 107392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, R.M.; E Freedland, K.; Veith, R.C.; E Cryer, P.; A Skala, J.; Lynch, T.; Jaffe, A.S. Major depression, heart rate, and plasma norepinephrine in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 45, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C.; Neylan, T.C.; Pipkin, S.S.; Browner, W.S.; Whooley, M.A. Depressive symptoms and 24-hour urinary norepinephrine excretion levels in patients with coronary disease: Findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grossman, F.; Potter, W.Z. Catecholamines in depression: A cumulative study of urinary norepinephrine and its major metabolites in unipolar and bipolar depressed patients versus healthy volunteers at the NIMH. Psychiatry Res. 1999, 87, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, W.Z.; Manji, H.K. Catecholamines in depression: An update. Clin. Chem. 1994, 40, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenstein, L.; Zugck, C.; Schellberg, D.; Nelles, M.; Froehlich, H.; Katus, H.; Remppis, A. Prevalence and prognostic significance of adrenergic escape during chronic beta-blocker therapy in chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2009, 11, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindahl, B.; Baron, T.; Erlinge, D.; Hadziosmanovic, N.; Nordenskjöld, A.; Gard, A.; Jernberg, T. Medical Therapy for Secondary Prevention and Long-Term Outcome in Patients with Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation 2017, 135, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.M.; Rosmaninho-Salgado, J.; Cortez, V.; Pereira, F.C.; Kaster, M.P.; Aveleira, C.A.; Ferreira, M.; Álvaro, A.R.; Cavadas, C. Impaired adrenal medullary function in a mouse model of depression induced by unpredictable chronic stress. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. J. Eur. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechin, F.; Van Der Dijs, B.; Orozco, B.; Lechin, M.E.; Baez, S.; Lechin, A.E.; Rada, I.; Acosta, E.; Arocha, L.; Jiménez, V.; et al. Plasma neurotransmitters, blood pressure, and heart rate during supine-resting, orthostasis, and moderate exercise conditions in major depressed patients. Biol. Psychiatry 1995, 38, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Holmes, C. Neuronal Source of Plasma Dopamine. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Mezey, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Aneman, A.; Friberg, P.; Eisenhofer, G. Is there a third peripheral catecholaminergic system? Endogenous dopamine as an autocrine/paracrine substance derived from plasma DOPA and inactivated by conjugation. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 1995, 18 (Suppl. 1), S93–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuchel, O. Peripheral dopamine in hypertension and associated conditions. J. Hum. Hypertens. 1999, 13, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, M.R.; Rukavina Mikusic, N.L.; Kouyoumdzian, N.M.; Kravetz, M.C.; Fernández, B.E. Atrial natriuretic peptide and renal dopaminergic system: A positive friendly relationship? BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 710781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaschitz, A.; Ritz, E.; Kienreich, K.; Pieske, B.; März, W.; Boehm, B.O.; Drechsler, C.; Meinitzer, A.; Pilz, S. Circulating dopamine and C-peptide levels in fasting nondiabetic hypertensive patients: The Graz Endocrine Causes of Hypertension study. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kox, M.; van Eijk, L.T.; Zwaag, J.; van den Wildenberg, J.; Sweep, F.C.G.J.; van der Hoeven, J.G.; Pickkers, P. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7379–7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van der Poll, T.; Coyle, S.M.; Barbosa, K.; Braxton, C.C.; Lowry, S.F. Epinephrine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha and potentiates interleukin 10 production during human endotoxemia. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Köhler, C.A.; Freitas, T.H.; Stubbs, B.; Maes, M.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; De Andrade, N.Q.; Morris, G.; Fernandes, B.S.; Brunoni, A.R.; et al. Peripheral Alterations in Cytokine and Chemokine Levels after Antidepressant Drug Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 4195–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoogeveen, R.C.; Morrison, A.; Boerwinkle, E.; Miles, J.S.; Rhodes, C.E.; Sharrett, A.R.; Ballantyne, C.M. Plasma MCP-1 level and risk for peripheral arterial disease and incident coronary heart disease: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Atherosclerosis 2005, 183, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Battista, A.P.; Rhind, S.G.; Hutchison, M.G.; Hassan, S.; Shiu, M.Y.; Inaba, K.; Topolovec-Vranic, J.; Neto, A.C.; Rizoli, S.B.; Baker, A.J. Inflammatory cytokine and chemokine profiles are associated with patient outcome and the hyperadrenergic state following acute brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armaiz-Pena, G.N.; Gonzalez-Villasana, V.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; Sadaoui, N.C.; Stone, R.L.; Matsuo, K.; Dalton, H.J.; Previs, R.A.; Jennings, N.B.; et al. Adrenergic regulation of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 leads to enhanced macrophage recruitment and ovarian carcinoma growth. Oncotarget 2014, 6, 4266–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amirshahrokhi, K.; Khalili, A.-R. Carvedilol attenuates paraquat-induced lung injury by inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokine MCP-1, NF-κB activation and oxidative stress mediators. Cytokine 2016, 88, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, H.; Kai, H.; Kajimoto, H.; Koga, M.; Takayama, N.; Mori, T.; Ikeda, A.; Yasuoka, S.; Anegawa, T.; Mifune, H.; et al. Exaggerated blood pressure variability superimposed on hypertension aggravates cardiac remodeling in rats via angiotensin II system-mediated chronic inflammation. Hypertension 2009, 54, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raedler, T.J. Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkman, H.O. Novel Treatment Targets Based on Insights in the Etiology of Depression: Role of IL-6 Trans-Signaling and Stress-Induced Elevation of Glutamate and ATP. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- von Dawans, B.; Ditzen, B.; Trueg, A.; Fischbacher, U.; Heinrichs, M. Effects of acute stress on social behavior in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 99, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wekenborg, M.K.; Von Dawans, B.; Hill, L.K.; Thayer, J.F.; Penz, M.; Kirschbaum, C. Examining reactivity patterns in burnout and other indicators of chronic stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 106, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, F.U.; Bae, Y.J.; Kratzsch, J.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. Internalized weight bias and cortisol reactivity to social stress. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 20, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, M.; Wirz, L.; Dickinson, P.; Pruessner, J.C. Laughter yoga reduces the cortisol response to acute stress in healthy individuals. Stress 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, J.; Nater, U.M. How Cortisol Reactivity Influences Prosocial Decision-Making: The Moderating Role of Sex and Empathic Concern. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gecaite, J.; Burkauskas, J.; Brozaitiene, J.; Mickuviene, N. Cardiovascular Reactivity to Acute Mental Stress: The importance of typed personality, trait anxiety, and depression symptoms in patients after acute coronary syndromes. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2019, 39, E12–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| +D−CAD (n = 23) | +D+CAD (n = 21) | −D+CAD (n = 26) | −D−CAD (n = 23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 32.3 ± 10.1 (17–55) | 27.9 ± 11.6 (3–50) | 14.4 ± 10.7 (1–37) | 9.5 ± 7.7 (0–24) |

| HADS anxiety | 12.5 ± 3.3 (3–18) | 10.7 ± 4.2 (3–18) | 5.7 ± 3.5 (0–12) | 3.7 ± 2.6 (0–9) |

| HADS depression | 11.9 ± 3.9 (8–18) | 11.1 ± 2.4 (8–15) | 3.6 ± 2.4 (0–7) | 2.0 ± 1.9 (0–7) |

| PASA threat | 3.6 ± 1.3 (1.3–5.8) | 3.4 ± 1.2 (1.0–6.0) | 2.7 ± 1.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.5 ± 1.0 (1.0–4.3) |

| PASA challenge | 4.4 ± 0.7 (3.0–5.3) | 3.9 ± 1.0 (1.8–6.0) | 3.9 ± 0.8 (2.8–5.5) | 3.8 ± 0.7 (2.3–5.0) |

| PASA primary appraisal | 4.0 ± 0.9 (2.4–5.4) | 3.7 ± 1.0 (1.4–5.8) | 3.3 ± 0.8 (2.3–4.8) | 3.2 ± 0.7 (2.0–4.4) |

| PASA self-concept | 3.5 ± 1.4 (1.0–5.5) | 4.1 ± 1.0 (2.5–5.8) | 4.1 ± 1.3 (1.0–6.0) | 4.4 ± 1.2 (1.8–6.0) |

| PASA control expectancy | 4.4 ± 0.9 (3.0–6.0) | 4.5 ± 0.7 (3.0–6.0) | 5.1 ± 0.8 (3.0–6.0) | 4.9 ± 0.9 (1.8–6.0) |

| PASA secondary appraisal | 4.0 ± 0.9 (2.4–5.3) | 4.3 ± 0.7 (3.4–5.4) | 4.6 ± 0.9 (2.9–6.0) | 4.7 ± 0.8 (2.9–5.8) |

| PASA stressindex | 0.02 ± 1.7 (−2.6–2.8) | −0.7 ± 1.4 (−4.0–1.1) | −1.4 ± 1.4 (−3.8–1.4) | −1.5 ± 1.3 (−3.8–0.9) |

| STAI S1 | 53.6 ± 10.4 (32–73) | 40.6 ± 9.9 (29–64) | 32.6 ± 9.6 (20–58) | 30.7 ± 7.7 (21–44) |

| STAI S2 | 56 ± 11.9 (34–77) | 47.3 ± 9.8 (27–66) | 39.6 ± 13.1 (22–66) | 31.9 ± 9.3 (21–58) |

| +D−CAD (n = 23) | +D+CAD (n = 21) | −D+CAD (n = 26) | −D−CAD (n = 23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 50 ± 7.3 (39–69) | 56 ± 8.6 (41–72) | 63 ± 9.6 * (44–75) | 52 ± 8.4 (41–71) |

| Gender (m/f) | 18/5 | 18/3 | 21/5 | 20/3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 3.2 (19.3–32.7) | 29.7 ± 3.5 (21.3–36.7) # | 26.8 ± 3 (19.9–32.1) | 26.4 ± 2.9 (21.0–33.1) |

| CCS | 1.5 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0 | ||

| NYHA | 1.4 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 1 |

| +D−CAD (N = 23, n/%) | +D+CAD (N = 21, n/%) | −D+CAD (N = 26, n/%) | −D−CAD (N = 23, n/%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β blockers | 1 (4) | 15 (71) | 23 (86) | 0 (0) |

| ACE-inhibitors | 0 (0) | 17 (81) | 19 (73) | 0 (0) |

| AT1-antagonists | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 6 (23) | 0 (0) |

| Ca-antagonists | 0 (0) | 4 (19) | 5 (19) | 0 (0) |

| diuretics | 0 (0) | 13 (62) | 9 (35) | 0 (0) |

| Statins | 1 (4) | 19 (91) | 24 (92) | 0 (0) |

| Antidepressants | 14 (61) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoppmann, U.; Engler, H.; Krause, S.; Rottler, E.; Hoech, J.; Szabo, F.; Radermacher, P.; Waller, C. Systemic Catecholaminergic Deficiency in Depressed Patients with and without Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 986. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050986

Hoppmann U, Engler H, Krause S, Rottler E, Hoech J, Szabo F, Radermacher P, Waller C. Systemic Catecholaminergic Deficiency in Depressed Patients with and without Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(5):986. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050986

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoppmann, Uta, Harald Engler, Sabrina Krause, Edit Rottler, Julia Hoech, Franziska Szabo, Peter Radermacher, and Christiane Waller. 2021. "Systemic Catecholaminergic Deficiency in Depressed Patients with and without Coronary Artery Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 5: 986. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050986

APA StyleHoppmann, U., Engler, H., Krause, S., Rottler, E., Hoech, J., Szabo, F., Radermacher, P., & Waller, C. (2021). Systemic Catecholaminergic Deficiency in Depressed Patients with and without Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(5), 986. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050986