Viscoelastometric Testing to Assess Hemostasis of COVID-19: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Methodology

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. A Concise Overview of the Different VET Devices

2.4.1. ROTEM

2.4.2. TEG

2.4.3. Quantra

2.4.4. ClotPro

3. Results

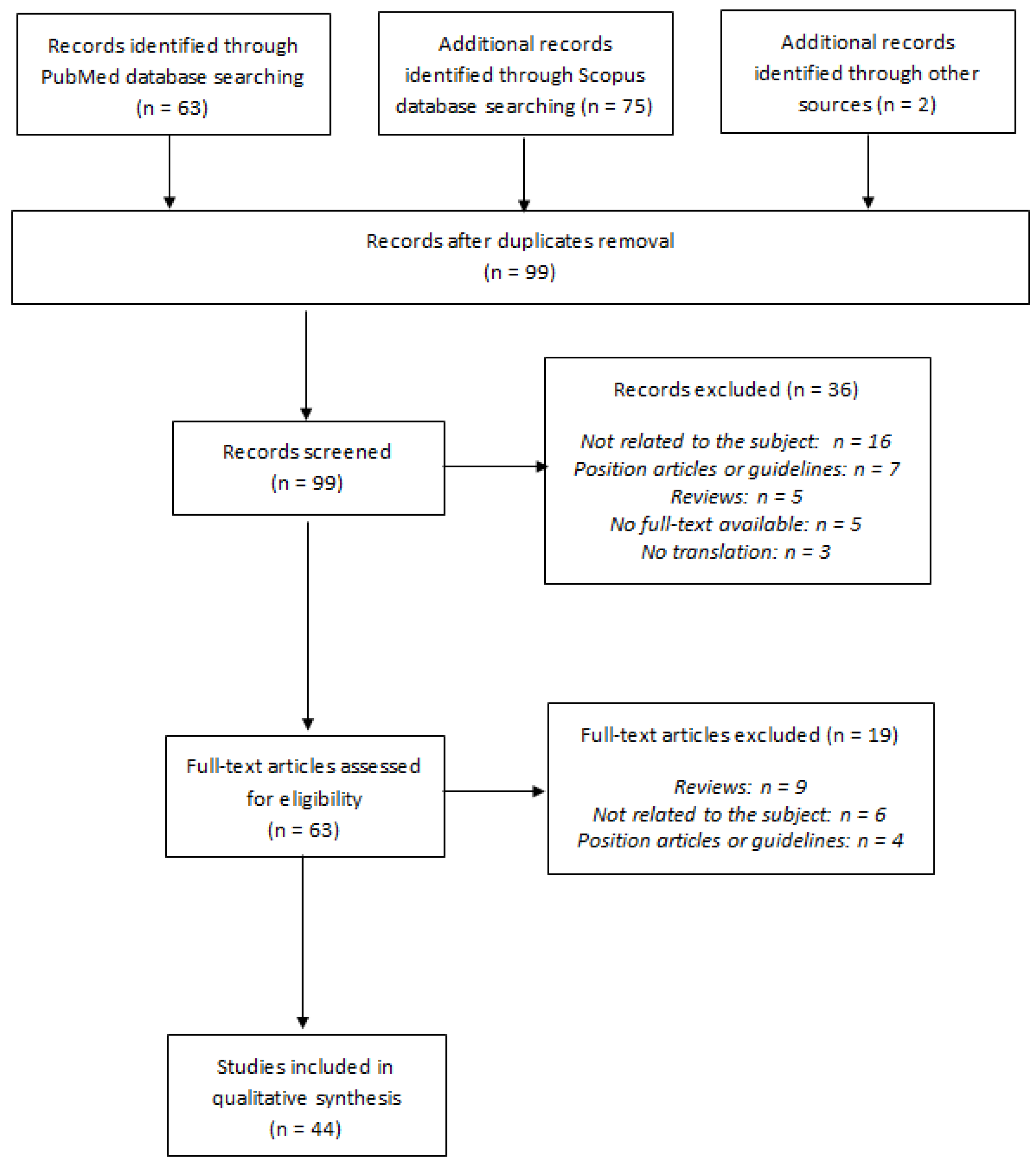

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Originality of Our Systematic Review as Compared to the Existing Ones on the Subject

3.3. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.4. Characteristics of the Included Patients

3.5. Results of the Viscoelastic Tests

3.5.1. ROTEM

3.5.2. TEG

3.5.3. Quantra

3.5.4. ClotPro

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Issues in VET Studies

4.2. Definition of a Hypercoagulable State by VET and Association with Thrombotic Events

4.3. Ability of VETs to Detect Hypofibrinolysis State and Association with Thrombotic Events

4.4. Correlation between Clauss Fibrinogen and Functional Fibrinogen Assessed by VETs

4.5. Impact of Differences in Anticoagulation Regimens (Type (UFH, LMWH) and Dosage)

4.6. Summary of the Conclusions of the Previously Published Reviews

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. ROTEM® Reagents and Parameters

| Assay | Reagent | Description | Heparin Neutralization |

|---|---|---|---|

| INTEM | Ellagic acid | Intrinsic pathway screening test | No |

| HEPTEM | Ellagic acid + Heparinase | Intrinsic pathway screening test with heparinase | Yes 1 |

| EXTEM | Tissue factor + Polybrene | Rapid overview of the coagulation process | Yes 2 |

| APTEM | Tissue factor + Aprotinin + Polybrene | Exploration of the fibrinolysis by comparison with the EXTEM results | Yes 2 |

| FIBTEM | Tissue factor + Cytochalasin D + Polybrene | Functional detection of the fibrinogen level after platelet inhibition by cytochalasin D | Yes 2 |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| CT (s) | Clotting time: time interval from the start of the run until a 2 mm clot forms |

| CFT (s) | Clot formation time: time interval from CT until a clot amplitude of 20 mm is reached |

| α angle (°) | Rate of clot formation |

| A(x) (mm) | Amplitude of the oscillation due to clotting x minutes after CT |

| MCF (mm) | Maximum clot firmness: maximum clot amplitude |

| LI(x) (%) | Clot lysis index: ratio between MCF and amplitude of the clot x minutes after CT |

| ML (%) | Maximum lysis: maximum fibrinolysis detected during the observation period, expressed as a percentage of MCF |

Appendix B. TEG® Reagents and Parameters (Haemonetics Corporation, Boston, MA, USA)

| Assay | Reagents for TEG5000 | Reagents for TEG6s | Description | Heparin Neutralization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RapidTEG (CRT) | Tissue factor + Kaolin + Heparinase if heparinase cups are used | Tissue factor + Kaolin | Rapid overview of the coagulation process | Yes (if heparinase cups were used for TEG5000), otherwise no |

| Kaolin TEG (CK) | Kaolin | Kaolin | Intrinsic pathway screening test | No |

| Kaolin TEG with heparinase (CKH) | Kaolin + Heparinase (heparinase cup) | Kaolin + Heparinase | Intrinsic pathway screening test with heparinase | Yes |

| TEG Functional Fibrinogen (CFF) | Tissue factor + Abciximab + Heparinase if heparinase cups are used | Tissue factor + Abciximab | Functional detection of the fibrinogen level after platelet inhibition by abciximab | Yes (if heparinase cups were used for TEG5000), otherwise no |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| R (min) | Reaction time: time to initial fibrin formation |

| K (min) | Kinetics time: time to clot formation |

| α angle (°) | Rate of clot formation |

| MA (mm) | Maximum amplitude: absolute clot strength |

| LY30 (%) | Fibrinolytic activity 30 min after maximum amplitude was reached |

Appendix C. Quantra® Reagents and Parameters (HemoSonics, LLC, Charlottesville, VA, USA)

| Parameter | Reagents | Description | Heparin Neutralization | Manufacturer’s Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT (s) | Kaolin (channel 1) | Clotting time after addition of kaolin | No | 113–164 s |

| CTH (s) | Kaolin + Heparinase (channel 2) | Clotting time with heparinase after addition of kaolin | Yes | 103–153 s |

| CT/CTH | None, calculated as the ratio of CT (channel 1) over CTH (channel 2) | Clot time ratio | NA 1 | <1.4 |

| CS (hPA) | Thromboplastin + Polybrene (channel 3) | Clot stiffness | Yes | 13–33.2 hPa |

| FCS (hPA) | Thromboplastin + Abciximab + Polybrene (channel 4) | Fibrinogen contribution to overall clot stiffness after platelet inhibition with abciximab | Yes | 1–3.7 hPa |

| PCS (hPA) | None, calculated as the difference between CS (channel 3) and FCS (channel 4) | Platelet contribution to clot stiffness | Yes | 11.9–29.8 hPa |

| Parameter | Reagents | Description | Heparin Neutralization | Manufacturer’s Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT (s) | Kaolin | Clotting time after addition of kaolin | No | 113–164 s |

| CS (hPA) | Thromboplastin + Polybrene | Clot stiffness | Yes | 13–33.2 hPa |

| CSL (%) | None, calculated as the normalized difference between the clot stiffness change after maximum clot stiffness in the absence of tranexamic acid and the corresponding clot stiffness change in the presence of tranexamic acid | Clot stability to lysis | Yes | 93–100% |

| FCS (hPA) | Thromboplastin + Abciximab + Polybrene | Fibrinogen contribution to overall clot stiffness after platelet inhibition with abciximab | Yes | 1–3.7 hPa |

| PCS (hPA) | None, calculated as the difference between CS and FCS | Platelet contribution to clot stiffness | Yes | 11.9–29.8 hPa |

Appendix D. ClotPro® Reagents and Parameters (enicor GmbH, Munich, Germany)

| Assay | Reagent | Description | Heparin Neutralization |

|---|---|---|---|

| IN-test | Ellagic acid | Intrinsic pathway screening test | No |

| HI-test | Ellagic acid + Heparinase | Intrinsic pathway screening test with heparinase | Yes |

| EX-test | Recombinant tissue factor + Polybrene | Rapid overview of the coagulation process | Yes |

| AP-test | Tissue factor + Aprotinin + Polybrene | Exploration of the fibrinolysis by comparison with the EX-test results | Yes |

| tPA-test | Recombinant tissue factor + Recombinant tPA + Polybrene | Exploration of the fibrinolysis by comparison with the EX-test results | Yes |

| FIB-test | Recombinant tissue factor + Cytolochalasin D + Abciximab + Polybrene | Functional detection of the fibrinogen level after dual platelet inhibition by cytochalasin D and abciximab | Yes |

| RVV-test | Reagent derived from Russell viper venom | Detection of factor Xa inhibitors (LMWH, DOAC) | No |

| ECA-test | Ecarin + Polybrene | Detection of direct thrombin antagonists | Yes |

| NA-test | None | Non-activated test for the exploration of non-activated coagulation in citrated blood | No |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| CT (s) | Clotting time: time interval from the start of the run until a 2 mm amplitude of oscillations due to clotting was reached |

| CFT (s) | Clot formation time: time interval from CT until a clot amplitude of 20 mm is reached |

| A(x) (mm) | Amplitude of the oscillation due to clotting x minutes after CT |

| MCF (mm) | Maximum clot firmness: maximum clot amplitude |

| ML (%) | Maximum lysis: maximum fibrinolysis detected during the observation period, expressed as a percentage of MCF |

References

- Hans, G.A.; Besser, M.W. The place of viscoelastic testing in clinical practice. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 173, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roullet, S.; de Maistre, E.; Ickx, B.; Blais, N.; Susen, S.; Faraoni, D.; Garrigue, D.; Bonhomme, F.; Godier, A.; Lasne, D.; et al. Position of the French Working Group on Perioperative Haemostasis (GIHP) on viscoelastic tests: What role for which indication in bleeding situations? Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2019, 38, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, N.S.; Davenport, R.; Pavord, S.; Mallett, S.V.; Kitchen, D.; Klein, A.A.; Maybury, H.; Collins, P.W.; Laffan, M. The use of viscoelastic haemostatic assays in the management of major bleeding: A British Society for Haematology Guideline. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 182, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katori, N.; Tanaka, K.A.; Szlam, F.; Levy, J.H. The Effects of Platelet Count on Clot Retraction and Tissue Plasminogen Activator-Induced Fibrinolysis on Thrombelastography. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 100, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganter, M.T.; Hofer, C.K. Coagulation Monitoring: Current Techniques and Clinical Use of Viscoelastic Point-of-Care Coagulation Devices. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arnolds, D.E.; Scavone, B.M. Thromboelastographic Assessment of Fibrinolytic Activity in Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Single-Center Observational Study. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C.; Ranucci, M.; Hochleitner, G.; Schöchl, H.; Schlimp, C.J. Assessing the Methodology for Calculating Platelet Contribution to Clot Strength (Platelet Component) in Thromboelastometry and Thrombelastography. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 121, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranucci, M.; Baryshnikova, E. Sensitivity of Viscoelastic Tests to Platelet Function. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranucci, M.; Di Dedda, U.; Baryshnikova, E. Platelet Contribution to Clot Strength in Thromboelastometry: Count, Function, or Both? Platelets 2020, 31, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlatescu, E.; Juffermans, N.P.; Thachil, J. The current status of viscoelastic testing in septic coagulopathy. Thromb. Res. 2019, 183, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Gando, S.; Iba, T.; Kim, P.Y.; Yeh, C.H.; Brohi, K.; Hunt, B.J.; Levy, J.H.; Draxler, D.F.; Stanworth, S.; et al. Defining trauma-induced coagulopathy with respect to future implications for patient management: Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E. Temporal Changes in Fibrinolysis following Injury. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huffmyer, J.L.; Fernandez, L.G.; Haghighian, C.; Terkawi, A.S.; Groves, D.S. Comparison of SEER Sonorheometry with Rotational Thromboelastometry and Laboratory Parameters in Cardiac Surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, B.; Görlinger, K.; Treml, B.; Tauber, H.; Fries, D.; Niederwanger, C.; Oswald, E.; Bachler, M. A comparison of the new ROTEM ® sigma with its predecessor, the ROTEM delta: ROTEM sigma reference intervals. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlinger, K.; Pérez-Ferrer, A.; Dirkmann, D.; Saner, F.; Maegele, M.; Calatayud, Á.A.P.; Kim, T.Y. The role of evidence-based algorithms for rotational thromboelastometry-guided bleeding management. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurbel, P.A.; Bliden, K.P.; Tantry, U.S.; Monroe, A.L.; Muresan, A.A.; Brunner, N.E.; Lopez-Espina, C.G.; Delmenico, P.R.; Cohen, E.; Raviv, G.; et al. First report of the point-of-care TEG: A technical validation study of the TEG-6S system. Platelets 2016, 27, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Donald, P.; Churilov, L.; Zia, F.; Bellomo, R.; Hart, G.; McCall, P.; Mårtensson, J.; Glassford, N.; Weinberg, L. Assessment of agreement and interchangeability between the TEG5000 and TEG6S thromboelastography haemostasis analysers: A prospective validation study. BMC Anesth. 2019, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Q.; Byrne, K.P.; Robinson, S.C. Clinical agreement and interchangeability of TEG5000 and TEG6s during cardiac surgery. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2020, 48, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, F.; Kramer, M.D.; Lawrence, M.B.; Oberhauser, J.P.; Walker, W.F. Sonorheometry: A noncontact method for the dynamic assessment of thrombosis. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 32, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, F.; Mauldin, F.W.; Lin-Schmidt, X.; Haverstick, D.M.; Lawrence, M.B.; Walker, W.F. A novel ultrasound-based method to evaluate hemostatic function of whole blood. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2010, 411, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferrante, E.A.; Blasier, K.R.; Givens, T.B.; Lloyd, C.A.; Fischer, T.J.; Viola, F. A Novel Device for the Evaluation of Hemostatic Function in Critical Care Settings. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michelson, E.A.; Cripps, M.W.; Ray, B.; Winegar, D.A.; Viola, F. Initial clinical experience with the Quantra QStat System in adult trauma patients. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2020, 5, e000581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachler, M.; Bösch, J.; Stürzel, D.P.; Hell, T.; Giebl, A.; Ströhle, M.; Klein, S.J.; Schäfer, V.; Lehner, G.F.; Joannidis, M.; et al. Impaired fibrinolysis in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberladstätter, D.; Voelckel, W.; Schlimp, C.; Zipperle, J.; Ziegler, B.; Grottke, O.; Schöchl, H. A prospective observational study of the rapid detection of clinically-relevant plasma direct oral anticoagulant levels following acute traumatic injury. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Shiga, T.; Konno, D.; Saito, K.; Aoyagi, T.; Oshima, K.; Kanamori, H.; Baba, H.; Tokuda, K.; Yamauchi, M. Screening of COVID-19-associated hypercoagulopathy using rotational thromboelastometry. J. Clin. Anesth. 2020, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavoni, V.; Gianesello, L.; Pazzi, M.; Stera, C.; Meconi, T.; Frigieri, F.C. Evaluation of coagulation function by rotation thromboelastometry in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 50, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boscolo, A.; Spiezia, L.; Correale, C.; Sella, N.; Pesenti, E.; Beghetto, L.; Campello, E.; Poletto, F.; Cerruti, L.; Cola, M.; et al. Different Hypercoagulable Profiles in Patients with COVID-19 Admitted to the Internal Medicine Ward and the Intensive Care Unit. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 1474–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.D.; Cordioli, R.L.; Campos Guerra, J.C.; Caldin da Silva, B.; dos Reis Rodrigues, R.; de Souza, G.M.; Midega, T.D.; Campos, N.S.; Carneiro, B.V.; Campos, F.N.D.; et al. Coagulation profile of COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU: An exploratory study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madathil, R.J.; Tabatabai, A.; Rabin, J.; Menne, A.R.; Henderson, R.; Mazzeffi, M.; Scalea, T.M.; Tanaka, K. Thromboelastometry and D-Dimer Elevation in Coronavirus-2019. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiezia, L.; Boscolo, A.; Poletto, F.; Cerruti, L.; Tiberio, I.; Campello, E.; Navalesi, P.; Simioni, P. COVID-19-Related Severe Hypercoagulability in Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Unit for Acute Respiratory Failure. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 998–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsantes, A.E.; Frantzeskaki, F.; Tsantes, A.G.; Rapti, E.; Rizos, M.; Kokoris, S.I.; Paramythiotou, E.; Katsadiotis, G.; Karali, V.; Flevari, A.; et al. The haemostatic profile in critically ill COVID-19 patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulant therapy: An observational study. Medicine 2020, 99, e23365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghafry, M.; Aygun, B.; Appiah-Kubi, A.; Vlachos, A.; Ostovar, G.; Capone, C.; Sweberg, T.; Palumbo, N.; Goenka, P.; Wolfe, L.W.; et al. Are children with SARS-CoV-2 infection at high risk for thrombosis? Viscoelastic testing and coagulation profiles in a case series of pediatric patients. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creel-Bulos, C.; Auld, S.C.; Caridi-Scheible, M.; Barker, N.; Friend, S.; Gaddh, M.; Kempton, C.L.; Maier, C.L.; Nahab, F.; Sniecinski, R. Fibrinolysis Shutdown and Thrombosis in A COVID-19 ICU. Shock 2020, 55, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoechter, D.J.; Becker-Pennrich, A.; Langrehr, J.; Bruegel, M.; Zwissler, B.; Schaefer, S.; Spannagl, M.; Hinske, L.C.; Zoller, M. Higher procoagulatory potential but lower DIC score in COVID-19 ARDS patients compared to non-COVID-19 ARDS patients. Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, D.J.; Eiseman, K.; Kirsch, H.; Yoh, N.; Boehme, A.; Agarwal, S.; Park, S.; Connolly, E.S.; Claassen, J.; Wagener, G. Brief Report: Hypercoagulable viscoelastic blood clot characteristics in critically-ill COVID-19 patients and associations with thrombotic complications. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 90, e7–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Hutchinson, N.; Görlinger, K. Hyper- and hypocoagulability in COVID-19 as assessed by thromboelastometry. Two case reports. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, J.S.; Burnett, A.E.; Rollins-Raval, M.A.; Griggs, J.R.; Rosenbaum, L.; Nielsen, N.D.; Harkins, M.S. Viscoelastic testing in COVID-19: A possible screening tool for severe disease? Transfusion 2020, 60, 1131–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nougier, C.; Benoit, R.; Simon, M.; Desmurs-Clavel, H.; Marcotte, G.; Argaud, L.; David, J.S.; Bonnet, A.; Negrier, C.; Dargaud, Y. Hypofibrinolytic state and high thrombin generation may play a major role in SARS-COV2 associated thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2215–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.; Roux, O.; Moyer, J.-D.; Paugam-Burtz, C.; Boudaoud, L.; Ajzenberg, N.; Faille, D.; de Raucourt, E. Fibrinolysis Resistance: A Potential Mechanism Underlying COVID-19 Coagulopathy. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 1343–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almskog, L.M.; Wikman, A.; Svensson, J.; Wanecek, M.; Bottai, M.; van der Linden, J.; Ågren, A. Rotational thromboelastometry results are associated with care level in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collett, L.W.; Gluck, S.; Strickland, R.M.; Reddi, B.J. Evaluation of coagulation status using viscoelastic testing in intensive care patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): An observational point prevalence cohort study. Aust. Crit. Care 2021, 34, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibañez, C.; Perdomo, J.; Calvo, A.; Ferrando, C.; Reverter, J.C.; Tassies, D.; Blasi, A. High D dimers and low global fibrinolysis coexist in COVID19 patients: What is going on in there? J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, J.M.; Magomedov, A.; Kurreck, A.; Münch, F.H.; Koerner, R.; Kamhieh-Milz, J.; Kahl, A.; Gotthardt, I.; Piper, S.K.; Eckardt, K.U.; et al. Thromboembolic complications in critically ill COVID-19 patients are associated with impaired fibrinolysis. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, V.; Gianesello, L.; Pazzi, M.; Horton, A.; Suardi, L.R. Derangement of the coagulation process using subclinical markers and viscoelastic measurements in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia and non-coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2021, 32, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiezia, L.; Campello, E.; Cola, M.; Poletto, F.; Cerruti, L.; Poretto, A.; Simion, C.; Cattelan, A.; Vettor, R.; Simioni, P. More Severe Hypercoagulable State in Acute COVID-19 Pneumonia as Compared with Other Pneumonia. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, J.; Almskog, L.; Liliequist, A.; Grip, J.; Fux, T.; Rysz, S.; Ågren, A.; Oldner, A.; Ståhlberg, M. Thromboembolism, Hypercoagulopathy, and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Critically Ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients: A before and after Study of Enhanced Anticoagulation. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasi, A.; Meijenfeldt, F.A.; Adelmeijer, J.; Calvo, A.; Ibañez, C.; Perdomo, J.; Reverter, J.C.; Lisman, T. In vitro hypercoagulability and ongoing in vivo activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis in COVID-19 patients on anticoagulation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2646–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Veenendaal, N.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; Meijer, K.; van der Voort, P.H.J. Rotational thromboelastometry to assess hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients. Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M.; Tomey, M.I.; Ghia, S.; Katz, D.; Derr, K.; Narula, J.; Bhatt, H.V. Rotational thromboelastometry in young, previously healthy patients with SARS-Cov2. J. Clin. Anesth. 2020, 67, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, F.L.; Vogler, T.O.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Wohlauer, M.V.; Urban, S.; Nydam, T.L.; Moore, P.K.; McIntyre, R.C., Jr. Fibrinolysis Shutdown Correlation with Thromboembolic Events in Severe COVID-19 Infection. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020, 231, 193–203.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigada, M.; Bottino, N.; Tagliabue, P.; Grasselli, G.; Novembrino, C.; Chantarangkul, V.; Pesenti, A.; Peyvandi, F.; Tripodi, A. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1738–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, P.-Y.; Pierrou, C.; Noel, A.; Paris, R.; Gaudray, E.; Martin, E.; Contargyris, C.; Bélot-De Saint Léger, F.; Lyochon, A.; Astier, H.; et al. Complex and prolonged hypercoagulability in coronavirus disease 2019 intensive care unit patients: A thromboelastographic study. Aust. Crit. Care 2021, 34, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hightower, S.; Ellis, H.; Collen, J.; Ellis, J.; Grasso, I.; Roswarski, J.; Cap, A.P.; Chung, K.; Prescher, L.; Kavanaugh, M.; et al. Correlation of indirect markers of hypercoagulability with thromboelastography in severe coronavirus 2019. Thromb. Res. 2020, 195, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maatman, T.K.; Jalali, F.; Feizpour, C.; Douglas, A.; McGuire, S.P.; Kinnaman, G.; Hartwell, J.L.; Maatman, B.T.; Kreutz, R.P.; Kapoor, R.; et al. Routine Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis May Be Inadequate in the Hypercoagulable State of Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit. Care Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortus, J.R.; Manek, S.E.; Brubaker, L.S.; Loor, M.; Cruz, M.A.; Trautner, B.W.; Rosengart, T.K. Thromboelastographic Results and Hypercoagulability Syndrome in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Who Are Critically Ill. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2011192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadd, C.; Rowe, T.; Nazeef, M.; Kory, P.; Sultan, S.; Faust, H. Thromboelastography to Detect Hypercoagulability and Reduced Fibrinolysis in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients. Crit. Care Explor. 2020, 2, e0192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriditsky, E.; Horowitz, J.M.; Merchan, C.; Ahuja, T.; Brosnahan, S.B.; McVoy, L.; Berger, J.S. Thromboelastography Profiles of Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit. Care Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, M.G.; Maviglia, R.; Consalvo, L.M.; Grieco, D.L.; Montini, L.; Mercurio, G.; Nardi, G.; Pisapia, L.; Cutuli, S.L.; Biasucci, D.G.; et al. Thromboelastography clot strength profiles and effect of systemic anticoagulation in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: A prospective, observational study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 12466–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stattin, K.; Lipcsey, M.; Andersson, H.; Pontén, E.; Bülow Anderberg, S.; Gradin, A.; Larsson, A.; Lubenow, N.; von Seth, M.; Rubertsson, S.; et al. Inadequate prophylactic effect of low-molecular weight heparin in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J. Crit. Care 2020, 60, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlot, E.A.; Van den Dool, E.J.; Hackeng, C.M.; Sohne, M.; Noordzij, P.G.; Van Dongen, E.P.A. Anti Xa activity after high dose LMWH thrombosis prophylaxis in covid 19 patients at the intensive care unit. Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.V.; Arachchillage, D.J.; Ridge, C.A.; Bianchi, P.; Doyle, J.F.; Garfield, B.; Ledot, S.; Morgan, C.; Passariello, M.; Price, S.; et al. Pulmonary Angiopathy in Severe COVID-19: Physiologic, Imaging, and Hematologic Observations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, N.; Atallah, B.; El Nekidy, W.S.; Sadik, Z.G.; Park, W.M.; Mallat, J. Thromboelastography findings in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Donovan, K.; McHugh, A.; Pandey, M.; Aaron, L.; Bradbury, C.A.; Stanworth, S.J.; Alikhan, R.; Von Kier, S.; Maher, K.; et al. Thrombotic and haemorrhagic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A multicentre observational study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, B.E.; Chia, Y.W.; Sum, C.L.L.; Kuperan, P.; Chan, S.S.W.; Ling, L.M.; Tan, G.W.L.; Goh, S.S.N.; Wong, L.H.; Lim, S.P.; et al. Global haemostatic tests in rapid diagnosis and management of COVID-19 associated coagulopathy in acute limb ischaemia. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 50, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, P.; Hékimian, G.; Lejeune, M.; Chommeloux, J.; Desnos, C.; Pineton De Chambrun, M.; Martin-Toutain, I.; Nieszkowska, A.; Lebreton, G.; Bréchot, N.; et al. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Is a Major Contributor to COVID-19–Associated Coagulopathy: Insights From a Prospective, Single-Center Cohort Study. Circulation 2020, 142, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranucci, M.; Ballotta, A.; Di Dedda, U.; Bayshnikova, E.; Dei Poli, M.; Resta, M.; Falco, M.; Albano, G.; Menicanti, L. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1747–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zátroch, I.; Smudla, A.; Babik, B.; Tánczos, K.; Kóbori, L.; Szabó, Z.; Fazakas, J. Procoagulatio, hypercoagulatio és fibrinolysis „shut down” kimutatása ClotPro® viszkoelasztikus tesztek segítségével COVID–19-betegekben.: (A COVID–19-pandémia orvosszakmai kérdései). Orv. Hetil. 2020, 161, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlinger, K.; Dirkmann, D.; Gandhi, A.; Simioni, P. COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy and Inflammatory Response: What Do We Know Already and What Are the Knowledge Gaps? Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 1324–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantes, A.E.; Tsantes, A.G.; Kokoris, S.I.; Bonovas, S.; Frantzeskaki, F.; Tsangaris, I.; Kopterides, P. COVID-19 Infection-Related Coagulopathy and Viscoelastic Methods: A Paradigm for Their Clinical Utility in Critical Illness. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, J.; Ergang, A.; Mason, D.; Dias, J.D. The Role of TEG Analysis in Patients with COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słomka, A.; Kowalewski, M.; Żekanowska, E. Hemostasis in Coronavirus Disease 2019-Lesson from Viscoelastic Methods: A Systematic Review. Thromb. Haemost. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Young, K.; Potter, J.; Madan, I. A review of grading systems for evidence-based guidelines produced by medical specialties. Clin. Med. 2010, 10, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susen, S.; Tacquard, C.A.; Godon, A.; Mansour, A.; Garrigue, D.; Nguyen, P.; Godier, A.; Testa, S.; Levy, J.H.; Albaladejo, P.; et al. Prevention of thrombotic risk in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and hemostasis monitoring. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 304–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivas, D.; Roldán, V.; Esteve-Pastor, M.A.; Roldán, I.; Tello-Montoliu, A.; Ruiz-Nodar, J.M.; Cosín-Sales, J.; Gámez, J.M.; Consuegra, L.; Ferreiro, J.L.; et al. Recomendaciones sobre el tratamiento antitrombótico durante la pandemia COVID-19. Posicionamiento del Grupo de Trabajo de Trombosis Cardiovascular de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Quasim, I.; Steven, M.; Moise, S.F.; Shelley, B.; Schraag, S.; Sinclair, A. Interoperator and Intraoperator Variability of Whole Blood Coagulation Assays: A Comparison of Thromboelastography and Rotational Thromboelastometry. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2014, 28, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, D.; Kitchen, S.; Jennings, I.; Woods, T.; Walker, I. Quality Assurance and Quality Control of Thrombelastography and Rotational Thromboelastometry: The UK NEQAS for Blood Coagulation Experience. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolai, L.; Leunig, A.; Brambs, S.; Kaiser, R.; Weinberger, T.; Weigand, M.; Muenchhoff, M.; Hellmuth, J.C.; Ledderose, S.; Schulz, H.; et al. Immunothrombotic Dysregulation in COVID-19 Pneumonia Is Associated with Respiratory Failure and Coagulopathy. Circulation 2020, 142, 1176–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Szlam, F.; Bolliger, D.; Nishimura, T.; Chen, E.P.; Tanaka, K.A. The Impact of Hematocrit on Fibrin Clot Formation Assessed by Rotational Thromboelastometry. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 115, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C.; Rahe-Meyer, N. Effect of haematocrit on fibrin-based clot firmness in the FIBTEM test. Blood Transfus. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.D.; Lopez-Espina, C.G.; Bliden, K.; Gurbel, P.; Hartmann, J.; Achneck, H.E. TEG®6s system measures the contributions of both platelet count and platelet function to clot formation at the site-of-care. Platelets 2020, 31, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schlimp, C.J.; Solomon, C.; Ranucci, M.; Hochleitner, G.; Redl, H.; Schöchl, H. The Effectiveness of Different Functional Fibrinogen Polymerization Assays in Eliminating Platelet Contribution to Clot Strength in Thromboelastometry. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C.; Sørensen, B.; Hochleitner, G.; Kashuk, J.; Ranucci, M.; Schöchl, H. Comparison of Whole Blood Fibrin-Based Clot Tests in Thrombelastography and Thromboelastometry. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 114, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C.; Baryshnikova, E.; Schlimp, C.J.; Schöchl, H.; Asmis, L.M.; Ranucci, M. FIBTEM PLUS Provides an Improved Thromboelastometry Test for Measurement of Fibrin-Based Clot Quality in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Anesth. Analg. 2013, 117, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAnda, A.; Levy, G.; Kinsky, M.; Sanjoto, P.; Garcia, M.; Avandsalehi, K.R.; Diaz, G.; Yates, S.G. Comparison of the Quantra QPlus System with Thromboelastography in Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillissen, A.; van den Akker, T.; Caram-Deelder, C.; Henriquez, D.D.C.A.; Bloemenkamp, K.W.M.; Eikenboom, J.; van der Bom, J.G.; de Maat, M.P.M. Comparison of thromboelastometry by ROTEM ® Delta and ROTEM ® Sigma in women with postpartum haemorrhage. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2019, 79, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, B.; Voelckel, W.; Zipperle, J.; Grottke, O.; Schöchl, H. Comparison between the new fully automated viscoelastic coagulation analysers TEG 6s and ROTEM Sigma in trauma patients: A prospective observational study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.S.; Welsby, I.J.; Naik, B.I.; Tanaka, K.; Hauck, J.N.; Greenberg, C.S.; Winegar, D.A.; Viola, F. Multicenter Evaluation of the Quantra QPlus System in Adult Patients Undergoing Major Surgical Procedures. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.; Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.; Thomas, S.; Lune, S.V.; Zimmer, D.; Dynako, J.; Hake, D.; Crowell, Z.; McCauley, R.; et al. Use of Viscoelastography in Malignancy-Associated Coagulopathy and Thrombosis: A Review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 45, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, W.; Lunati, M.; Maceroli, M.; Ernst, A.; Staley, C.; Johnson, R.; Schenker, M. Ability of Thromboelastography to Detect Hypercoagulability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 34, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahsheh, Y.; Ho, K.M. Use of viscoelastic tests to predict clinical thromboembolic events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2018, 100, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whyte, C.; Mitchell, J.; Mutch, N. Platelet-Mediated Modulation of Fibrinolysis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2017, 43, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raza, I.; Davenport, R.; Rourke, C.; Platton, S.; Manson, J.; Spoors, C.; Khan, S.; De’Ath, H.D.; Allard, S.; Hart, D.P.; et al. The incidence and magnitude of fibrinolytic activation in trauma patients: Fibrinolytic activation in trauma patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstaff, C. Measuring Fibrinolysis. Hämostaseologie 2021, 41, 069–075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupesiz, A.; Rajpurkar, M.; Warrier, I.; Hollon, W.; Tosun, O.; Lusher, J.; Chitlur, M. Tissue plasminogen activator induced fibrinolysis: Standardization of method using thromboelastography: Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2010, 21, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiper, G.J.A.J.M.; Kleinegris, M.-C.F.; van Oerle, R.; Spronk, H.M.H.; Lancé, M.D.; ten Cate, H.; Henskens, Y.M. Validation of a modified thromboelastometry approach to detect changes in fibrinolytic activity. Thromb. J. 2016, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dirkmann, D.; Radü-Berlemann, J.; Görlinger, K.; Peters, J. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator–evoked hyperfibrinolysis is enhanced by acidosis and inhibited by hypothermia but still can be blocked by tranexamic acid. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 74, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallimore, M.J.; Harris, S.L.; Tappenden, K.A.; Winter, M.; Jones, D.W. Urokinase induced fibrinolysis in thromboelastography: A model for studying fibrinolysis and coagulation in whole blood. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 2506–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigada, M.; Zacchetti, L.; L’Acqua, C.; Cressoni, M.; Anzoletti, M.B.; Bader, R.; Protti, A.; Consonni, D.; D’Angelo, A.; Gattinoni, L. Assessment of Fibrinolysis in Sepsis Patients with Urokinase Modified Thromboelastography. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH); Office of Product Evaluation and Quality (OPEQ). Coagulation Systems for Measurement of Viscoelastic Properties: Enforcement Policy during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency (Revised); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021.

- Ranucci, M.; Di Dedda, U.; Baryshnikova, E. Trials and Tribulations of Viscoelastic-Based Determination of Fibrinogen Concentration. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Johnson, R.I.; Shaw, M. A comparison of fibrinogen measurement using TEG ® functional fibrinogen and Clauss in cardiac surgery patients. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2015, 37, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, B.I.; Durieux, M.E.; Knisely, A.; Sharma, J.; Bui-Huynh, V.C.; Yalamuru, B.; Terkawi, A.S.; Nemergut, E.C. SEER Sonorheometry Versus Rotational Thromboelastometry in Large Volume Blood Loss Spine Surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baryshnikova, E.; Di Dedda, U.; Ranucci, M. A Comparative Study of SEER Sonorheometry Versus Standard Coagulation Tests, Rotational Thromboelastometry, and Multiple Electrode Aggregometry in Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2019, 33, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, C.L.; Barker, N.A.; Sniecinski, R.M. Falsely Low Fibrinogen Levels in COVID-19 Patients on Direct Thrombin Inhibitors. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, e117–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, M. In Response. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, e119–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Juffermans, N.P.; Ranucci, M.; Connors, J.M.; Warkentin, T.E.; Ortel, T.L.; Levi, M.; Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. ISTH DIC subcommittee communication on anticoagulation in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2138–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppell, J.A.; Thalheimer, U.; Zambruni, A.; Triantos, C.K.; Riddell, A.F.; Burroughs, A.K.; Perry, D.J. The effects of unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin and danaparoid on the thromboelastogram (TEG): An in-vitro comparison of standard and heparinase-modified TEGs with conventional coagulation assays: Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2006, 17, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artang, R.; Frandsen, N.J.; Nielsen, J. Application of basic and composite thrombelastography parameters in monitoring of the antithrombotic effect of the low molecular weight heparin dalteparin: An in vivo study. Thromb. J. 2009, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekkesin, N.; Tekkesin, M.; Kaso, G. Thromboelastography for the monitoring of the antithrombotic effect of low-molecular-weight heparin after major orthopedic surgery. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2015, 15, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranucci, M.; Cotza, M.; Isgrò, G.; Carboni, G.; Ballotta, A.; Baryshnikova, E.; Surgical Clinical Outcome REsearch (SCORE) Group. Anti-Factor Xa–Based Anticoagulation during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Potential Problems and Possible Solutions. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittermayr, M.; Margreiter, J.; Velik-Salchner, C.; Klingler, A.; Streif, W.; Fries, D.; Innerhofer, P. Effects of protamine and heparin can be detected and easily differentiated by modified thrombelastography (Rotem®): An in vitro study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2005, 95, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, O.; Larsson, A.; Tynngård, N.; Schött, U. Thromboelastometry versus free-oscillation rheometry and enoxaparin versus tinzaparin: An in-vitro study comparing two viscoelastic haemostatic tests’ dose-responses to two low molecular weight heparins at the time of withdrawing epidural catheters from ten patients after major surgery. BMC Anesth. 2015, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spadarella, G.; Di Minno, A.; Donati, M.B.; Mormile, M.; Ventre, I.; Di Minno, G. From unfractionated heparin to pentasaccharide: Paradigm of rigorous science growing in the understanding of the in vivo thrombin generation. Blood Rev. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Cervellin, G.; Franchini, M.; Favaloro, E.J. Biochemical markers for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: The past, present and future. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2010, 30, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintigh, J.; Monagle, P.; Ignjatovic, V. A review of commercially available thrombin generation assays. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 2, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninivaggi, M.; de Laat-Kremers, R.M.W.; Carlo, A.; de Laat, B. ST Genesia reference values of 117 healthy donors measured with STG-BleedScreen, STG-DrugScreen and STG-ThromboScreen reagents. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 5, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffen, R.; Kleinegris, M.-C.F.; Loubele, S.T.B.G.; Pluijmen, P.H.M.; Fens, D.; van Oerle, R.; Ten Cate, H.; Spronk, H.M. Preanalytic variables of thrombin generation: Towards a standard procedure and validation of the method. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2012, 10, 2544–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.; Hoppensteadt, D.; Bontekoe, E.; Farooqui, A.; Jeske, W.; Fareed, J. Comparative Anticoagulant and Thrombin Generation Inhibitory Profile of Heparin, Sulodexide and Its Components. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Off. J. Int. Acad Clin. Appl. Thromb. 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Berg, T.W.; Hulshof, A.-M.M.; Nagy, M.; van Oerle, R.; Sels, J.-W.; van Bussel, B.; Ten Cate, H.; Henskens, Y.; Spronk, H.M.H. Suggestions for global coagulation assays for the assessment of COVID-19 associated hypercoagulability. Thromb. Res. 2021, 201, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouck, E.G.; Denorme, F.; Holle, L.A.; Middelton, E.A.; Blair, A.; de Laat, B.; Schiffman, J.D.; Yost, C.C.; Rondina, M.T.; Wolberg, A.S.; et al. COVID-19 and Sepsis Are Associated with Different Abnormalities in Plasma Procoagulant and Fibrinolytic Activity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, M.; Sitzia, C.; Baryshnikova, E.; Di Dedda, U.; Cardani, R.; Martelli, F.; Corsi Romanelli, M. Covid-19-Associated Coagulopathy: Biomarkers of Thrombin Generation and Fibrinolysis Leading the Outcome. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.; MacDonald, S.; Edwards, T.; Bridgeman, C.; Hayman, M.; Sharp, M.; Cox-Morton, S.; Duff, E.; Mahajan, S.; Moore, C.; et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 coagulopathy; laboratory characterization using thrombin generation and nonconventional haemostasis assays. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistolini, A.; Ruberto, F.; Alessandri, F.; Santoro, C.; Barone, F.; Cristina Puzzolo, M.; Ceccarelli, G.; De Luca, M.L.; Mancone, M.; Alvaro, D.; et al. Effect of low or high doses of low-molecular-weight heparin on thrombin generation and other haemostasis parameters in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.; Michaux, I.; Lessire, S.; Douxfils, J.; Dogné, J.-M.; Bareille, M.; Horlait, G.; Bulpa, P.; Chapelle, C.; Laporte, S.; et al. Prothrombotic disturbances of hemostasis of patients with severe COVID-19: A prospective longitudinal observational study. Thromb. Res. 2021, 197, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campello, E.; Bulato, C.; Spiezia, L.; Boscolo, A.; Poletto, F.; Cola, M.; Gavasso, S.; Simion, C.; Radu, C.M.; Cattelan, A.; et al. Thrombin generation in patients with COVID-19 with and without thromboprophylaxis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.; Lecompte, T.; Douxfils, J.; Lessire, S.; Dogné, J.M.; Chatelain, B.; Testa, S.; Gouin-Thibault, I.; Gruel, Y.; Medcalf, R.L.; et al. Management of the thrombotic risk associated with COVID-19: Guidance for the hemostasis laboratory. Thromb. J. 2020, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | All patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection regardless of age | Pregnancy Pre-existing coagulation disorder |

| Intervention | Viscoelastometric testing performed | - |

| Comparison | Reference values (manufacturer’s based or healthy controls) ICU COVID-19 patients and non-ICU COVID-19 patients ICU COVID-19 patients and ICU non-COVID-19 patients | - |

| Outcomes | VET parameters in COVID-19 patients Difference in VET parameters between ICU COVID-19 patients and non-ICU COVID-19 patients Difference in VET parameters between ICU COVID-19 patients and ICU non-COVID-19 patients Association between VET parameters and clinical outcomes Association between VET parameters and Clauss fibrinogen | - |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials Observational clinical studies Case reports | Opinion papers Review papers Healthcare guidelines Protocol Non-human or in vitro studies |

| First Author (Title) | Type of the Review | Aim of the Review | Number and Type of Studies Included | VET Devices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Görlinger et al. [69] (COVID-19 associated coagulopathy and inflammatory response: what do we know already and what are the knowledge gaps?) | Narrative review | Review of coagulation abnormalities and inflammatory response associated with COVID-19 | 8 studies (5 prospective, 3 retrospective) | ROTEM, TEG, Quantra |

| Tsantes et al. [70] (COVID-19 Infection-Related Coagulopathy and Viscoelastic Methods: A Paradigm for Their Clinical Utility in Critical Illness) | Narrative review | Evaluation of the usefulness of VETs in clinical practice to guide anticoagulant treatments or predict prognosis | 13 studies (8 prospective, 5 retrospective) | ROTEM, TEG, Quantra |

| Hartmann et al. [71] (The Role of TEG Analysis in Patients with COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy: A Systematic Review) | Systematic review | Evaluation of the usefulness of TEG in clinical practice to identify and manage hypercoagulation associated with COVID-19 | 15 studies (5 prospective, 9 retrospective and one case report) | TEG |

| Słomka et al. [72] (Hemostasis in Coronavirus Disease 2019-Lesson from Viscoelastic Methods: A Systematic Review) | Systematic review | Evaluation of the performance of TEG and TEM in the assessment of blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients with COVID-19 | 10 studies (2 prospective, 8 retrospective) | ROTEM, TEG |

| First Author (Country) | Device | Study Design | Ward | n | Number of Patients with Viscoelastic Test Performed | Timing of Assay | Number of Patients with Invasive Mechanical Ventilation (n) | Number of Patients under ECMO (n) | Number of Patients with Renal Replacement Therapy (n) | Age 1 | Number of COVID-19 Patients with Thrombotic Events | Diagnosis of Thrombotic Events | Anticoagulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwasaki et al. (Japan) [26] | ROTEM (NS) | Case report | ICU | 1 | 1 | 1 day after ICU admission | 1 | NP | NP | 57 | None | NP | None until TE, then UFH 10,000 IU/d |

| Pavoni et al. (Italy) [27] | ROTEM gamma | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 40 | 40 | ICU admission, then 5 and 10 days later | 4/40 | NP | NP | 61 ± 13 | 20/40 patients (6 DVT, 2 TE, 12 catheter related thrombosis) | Systematic screening from common femoral vein by ultrasound | Enoxaparin 40–60 mg/d according to local protocol |

| Boscolo et al. (Italy) [28] | ROTEM delta | Prospective observational study | ICU | 32 | 32 | NP | 21/32 | NP | NP | 68 (62–75) | 11/32 patients | No systematic screening | NP |

| IMW | 32 | 32 | None | None | None | 61 (53–71) | 3/32 patients | ||||||

| Corrêa et al. (Brazil) [29] | ROTEM delta | Prospective observational study | ICU | 30 | 30 | ICU admission, then 1, 3, 7 and 14 days later | 27/30 | NP | 10/30 | 61 (52–83) | 6/30 patients (4 DVT, 2 PE) | NP | At least prophylactic UFH or LMWH |

| Madathil et al. (USA) [30] | ROTEM delta | Prospective observational study | ICU | 11 | 11 | ICU admission, then 24–48 h later | 11/11 | NP | NP | 53 (45.5–65.5) | NP | NP | NP |

| Spiezia et al. (Italy) [31] | ROTEM delta | Prospective observational case control study | ICU | 22 | 22 | ICU admission | 19/22 | NP | NP | 67 ± 8 | 5/22 patients (DVT) | NP | Prophylactic LMWH |

| Tsantes et al. (Greece) [32] | ROTEM delta | Prospective observational study | ICU COVID-19 patients | 11 | 11 | NP | NP | NP | NP | 78 (67–71) | NP | NP | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg bid |

| ICU non COVID-19 patients | 9 | 9 | NP | NP | NP | NP | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg od | ||||||

| IMW COVID-19 patients | 21 | 21 | NP | NP | NP | 73 (50–88) | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg od | ||||||

| Al-Ghafry et al. (USA) [33] | ROTEM delta | Retrospective observational study | PICU (n = 5) and PW (n = 3) | 8 | 8 | 1 to 4 days after hospital admission | None | None | None | 12.9 (2–20) | None | NP | Prophylactic enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg bid according to oxygen requirement and D-dimers levels, escalated to therapeutic dose (1 mg/kg bid) if clinical deterioration |

| Creel-Bulos et al. (USA) [34] | ROTEM delta | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 25 | 25 | NP | NP | NP | NP | 63 (53–77) | 9/25 patients (7 DVT, 4 PE, 1 arterial thrombosis) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | Prophylactic LMWH or UFH |

| Hoechter et al. (Germany) [35] | ROTEM delta | Retrospective observational case control study | ICU COVID-19 pneumonia | 22 | 11 | Within 48 h after ICU admission | 22/22 | NP | NP | 64 (52–70) | NP | NP | Prophylactic UFH according to local guidelines |

| ICU non COVID-19 pneumonia | 14 | 14 | NP | 14/14 | NP | NP | 49 (36–57) | ||||||

| Roh et al. (USA) [36] | ROTEM delta | Retrospective observational case control study | ICU | 30 | 30 | ICU admission | NP | NP | NP | 63 ± 12 | 10/30 patients (3 DVT, 1 PE, 1 both DVT and PE, 4 arterial thrombosis, 1 both arterial thrombosis and DVT) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | At least prophylactic UFH or LMWH |

| Kong et al. (United Kingdom) [37] | ROTEM delta | Case report | ICU | 1 | 1 | 2 h after ICU admission | No | No | No | 48 | None | NP | None until ROTEM analysis |

| ICU | 1 | 1 | NP | 1 | No | 1 | 68 | None | NP | ||||

| Raval et al. (USA) [38] | ROTEM delta | Case report | ICU | 1 | 1 | ICU admission | 1 | No | No | 63 | None | NP | None at admission, then UFH 7500 IU/8 h |

| Nougier et al. (France) [39] | Modified ROTEM delta (TEM-tPA) | Prospective observational case control study | ICU | 40 | 19 | NP | 33/40 | NP | 7/40 | 62.8 ± 13.1 | 14/40 patients (8 PE, 5 DVT, 1 arterial thrombosis) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | At least prophylactic UFH or LMWH |

| IMW | 38 | 4 | None | None | None | 60.2 ± 14.6 | NP | ||||||

| Weiss et al. (France) [40] | Modified ROTEM delta (TEM-tPA) | Prospective observational case control study | ICU | 5 | 5 | NP | NP | NP | NP | 57 ± 15 | 3/5 patients | NP | Thromboprophylaxis according to current guidelines |

| Almskog et al. (Sweden) [41] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective observational study | ICU | 20 | 20 | 1 day after hospital admission | NP | NP | NP | 62 (55–66) | NP | NP | At least prophylactic tinzaparin |

| IMW | 40 | 40 | NP | NP | NP | 61 (51–74) | |||||||

| Collett et al. (Australia) [42] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective observational study | ICU | 6 | 6 | NP | 5/6 | None | 2/6 | 69 (64.2–73) | 3/6 patients (1 PE, 1 catheter related thrombosis, 1 TE not clinically suspected) | NP | Enoxaparin 40 mg od |

| Ibañez et al. (Spain) [43] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective observational study | ICU | 19 | 19 | 24–48 h after ICU admission | NP | NP | NP | 61 (55–73) | 5/19 patients (2 DVT, 2 PE, 1 arterial thrombosis) | NP | Enoxaparin 40–80 mg/d according to local protocol |

| Kruse et al. (Germany) [44] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective observational study | ICU | 40 | 40 | ICU admission | 31/40 | 10/40 | 21/40 | 67 (57.3–76.6) | 23/40 patients (14 DVT, 4 PE, 3 ischemic stroke, 1 clotted ECMO cannula, 1 complete thrombosis of the ECMO circuit) | Systematic screening by ultrasound once a week | At least prophylactic LMWH (or argatroban if ECMO) |

| Pavoni et al. (Italy) [45] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective case controls observational study | ICU COVID-19 pneumonia | 20 | 20 | ICU admission, then 5 and 10 days later | 2/20 | NP | NP | 60.3 ± 15.2 | NP | NP | Enoxaparin 40–60 mg/d according to local protocol |

| ICU non COVID-19 pneumonia | 25 | 25 | 8/25 | NP | NP | 66.5 ± 18.8 | NP | ||||||

| Spiezia et al. (Italy) [46] | ROTEM sigma | Prospective case controls observational study | IMW COVID-19 pneumonia | 56 | 56 | Within 6 h after hospital admission | NP | NP | NP | 64 ± 15 | NP | NP | NP |

| IMW non COVID-19 pneumonia | 56 | 56 | 76 ± 11 | NP | |||||||||

| Van der Linden et al. (Sweden) [47] | ROTEM sigma | Cross-sectional study | ICU before enhanced anticoagulation | 12 | 12 | 13 (7–16) days after ICU admission | 12/12 | NP | 6/12 | 54 ± 9 | 7/12 patients (6 PE, 1 DVT) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | LMWH 129 ± 53 IU/kg/24 h or UFH infusion |

| ICU after enhanced anticoagulation | 14 | 14 | 18 (13–29) days after ICU admission | 14/14 | NP | 8/14 | 59 ± 8 | 5/14 patients (3 PE, 2 DVT) | LMWH 200 ± 82 IU/kg/24 h or UFH infusion | ||||

| Blasi et al. (Spain) [48] | ROTEM sigma | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 12 | 12 | 4 days after hospital admission | 12/12 | NP | NP | 69 (57–76) | NP | NP | At least prophylactic LMWH |

| IMW | 11 | 11 | None | NP | NP | 58 (42–74) | |||||||

| Van Veenendaal et al. (The Netherlands) [49] | ROTEM sigma | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 47 | 47 | NP | 47/47 | NP | NP | 63 (29–79) | 10/47 patients (10 PE) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | At least prophylactic UFH or LMWH |

| Lazar et al. (USA) [50] | ROTEM sigma | Case report | IMW | 1 | 1 | Hospital admission | No | No | No | NP | NP | NP | None at admission, then prophylactic UFH |

| IMW | 1 | 1 | No | No | No | NP | NP | None at admission, then enoxaparin 60 mg od | |||||

| Wright et al. (USA) [51] | TEG (NS) | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 44 | 44 | NP | 43/44 | 20/44 | NP | 54 (42–59) | 11/39 TE, 6/39 thrombotic stroke, 16/39 acute renal failure requiring dialysis | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | At least enoxaparin 40–60 mg od or UFH 10,000–15,000 IU per day |

| Panigada et al. (Italy) [52] | TEG5000 | Prospective observational study | ICU | 24 | 24 | NP | 24/24 | NP | NP | 56 (23–71) | NP | NP | At least prophylactic dose of LMWH or UFH |

| Cordier et al. (France) [53] | TEG5000 | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 24 | 24 | ICU admission, then at discharge from the ICU | NP | NP | NP | 69 (61–71) | 6/24 patients (4 isolated PE, 1 ischemic stroke, 1 both PE and ischemic stroke) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | Thromboprophylaxis according to current guidelines |

| Hightower et al. (USA) [54] | TEG5000 | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 5 | 5 | NP | 4/5 | None | None | 59 (38–69.5) | 2/5 patients | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical degradation | Enoxaparin 40 mg od or therapeutic UFH |

| Maatman et al. (USA) [55] | TEG5000 | Retrospective multi-center observational study | ICU | 109 | 12 | 3.5 days after hospital admission | 102/109 | NP | 16/109 | 61 ± 16 | 31/109 patients: 2/31 upon admission and 29/31 despite anticoagulation (26 isolated DVT, 1 isolated PE, 4 both DVT and PE) | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | UFH 5000 IU/8 h, 40 mg enoxaparin od or 30 mg enoxaparin bid |

| Mortus et al. (USA) [56] | TEG5000 | Retrospective cohort study | ICU | 21 | 21 | ICU admission | NP | 2/21 | 18/21 | 68 ± 11 | 13/21 patients for a total of 46 recorded events | NP | Standard DVT chemoprophylaxis upon admission with subsequent therapeutic anticoagulation (UFH or enoxaparin 2 mg/kg/d) if thrombotic complications |

| Sadd et al. (USA) [57] | TEG5000 | Retrospective observational cohort study | ICU | 10 | 10 | 2.5 days after ICU admission | 10/10 | NP | 3/10 | 58 (49–70) | 4/10 patients (3 AKI, 1 CRRT) | NP | Standard UFH or LMWH prophylaxis with subsequent therapeutic anticoagulation according to local guidelines |

| Yuriditsky et al. (USA) [58] | TEG5000 | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 64 | 64 | Within 72 h after ICU admission | NP | NP | NP | 64 (57–71) | 20/64 TE, 31/64 acute renal failure | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | Standard UFH or LMWH prophylaxis with subsequent therapeutic anticoagulation according to D-dimers levels or if thrombotic events |

| Bocci et al. (Italy) [59] | TEG6s | Prospective observational study | ICU | 40 | 40 | Within 24 h after ICU admission, then 7 days later | 29/40 | NP | NP | 67.5 (55–77) | 2/40 patients (2 PE) | Ultrasound and CT imaging not routinely used | Full-dose anticoagulation according to local protocols (enoxaparin 0,5 mg/kg/12 h, UFH 7500 IU/8 h or UFH infusion) |

| Stattin et al. (Sweden) [60] | TEG6s | Prospective observational study | ICU | 31 | 31 | NP | 24/31 | NP | NP | 65 (51–70) | 5/31 patients | NP | Prophylactic dalteparin (75–100 IU/kg) with anti-Xa levels target 0.2–0.4 IU/mL |

| Vlot et al. (The Netherlands) [61] | TEG6s | Prospective observational study | ICU | 16 | 16 | NP | 16/16 | NP | 6/16 | 67 (56–73) | None | No systematic screening | Increase prophylactic dose of LMWH: nadroparin 5700 IU bid (or 7600 IU according to body weight) instead of 2850 IU od |

| Patel et al. (United Kingdom) [62] | TEG6s | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 39 | 39 | NP | 39/39 | 20/39 | NP | 52.5 (29–79) | 15/39 patients with acute PE, 4/22 with DVT | Systematic screening by CT pulmonary angiography | At least prophylactic dose of LMWH or UFH with anti-Xa levels of 0.2–0.3 IU/mL |

| Salem et al. (United Arab Emirates) [63] | TEG6s | Retrospective observational study | ICU | 52 | 52 | NP | 46/52 | 7/52 | 16/52 | 53 (39–62) | 14/52 patients (8 DVT, 6 PE, 2 arterial thrombosis) | NP | Standard UFH or LMWH prophylaxis with subsequent therapeutic anticoagulation according to local guidelines |

| Shah et al. (United Kingdom) [64] | TEG6s | Multicenter retrospective observational study | ICU | 187 | 20 | NP | 166/187 | 6/187 | 80/187 | 57 (49–64) | 81/187 patients (42 PE, 22 DVT, 25 arterial thrombosis)Extracorporeal circuit disruption n = 23 | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | Standard weight-based LWMH prophylaxis with subsequent therapeutic anticoagulation if thrombotic events |

| Fan et al. (Singapore) [65] | TEG6s | Case report | IMW | 1 | 1 | 13 days after admission, 1 h after clinical sign of TE | No | No | No | 39 | 1 | Ultrasound or CT imaging based on clinical suspicion | None until TE, then therapeutic UFH 1300 IU/h (anti-Xa levels 0.4–0.6 IU/mL) |

| Masi et al. (France) [66] | Quantra | Prospective single-center cohort study | ICU COVID-19 ARDS | 17 | 17 | ICU admission | 17/17 | NP | NP | 48 (42–58) | 3/17 patients (3 PE) | NP | Thromboprophylaxis according to current guidelines |

| ICU non COVID-19 ARDS | 11 | 11 | 11/11 | NP | NP | 34 (28–55) | NP | NP | |||||

| Ranucci et al. (Italy) [67] | Quantra | Prospective observational study | ICU | 16 | 16 | 2–5 days after ICU admission, then 14 days after | 16/16 | NP | NP | 61 (55–65) | None | NP | Nadroparin 4000 IU bid then 6000 or 8000 IU bid according to BMI |

| Bachler et al. (Austria) [24] | ClotPro | Retrospective study | ICU | 20 | 20 | 8.5 (4.5–15) days after ICU admission | NP | NP | NP | 61.5 (56.25–68) | 2/20 patients | NP | Enoxaparin 80 (60–100) mg/day (n = 16) or argatroban (n = 4) |

| Zátroch et al. (Hungary) [68] | ClotPro | Case report | ICU | 1 | 1 | NP | No | No | No | 62 | 1 | NP | Enoxaparin 80 mg bid |

| 1 | 1 | NP | 1 | No | 1 | 80 | 1 | Enoxaparin 60 mg od | |||||

| 1 | 1 | NP | 1 | No | No | 84 | 1 | Enoxaparin 20 mg od |

| First Author (Country) | Device | n | Ward | Age | M:F Ratio | SOFA Score | APACHE II Score | SAPS II Score | SAPS III Score | DIC Score | SIC Score | BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | Comorbidities | CRP (mg/L) (<5 mg/L) * | Fibrinogen (mg/dL) (200–400 mg/dL) * | D-Dimers (µg/L) | Platelets (103/µL) (150–450 × 103/µL) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwasaki et al. (Japan) [26] | ROTEM (NS) | 1 | ICU | 57 | F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 391 | 334 | 1500 | 203 |

| Pavoni et al. (Italy) [27] | ROTEM gamma | 40 | ICU | 61 ± 13 | 24 M: 16 F | 4 ± 1 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28.4 ± 4.7 | Yes 5 | NP | 896 ± 110 | 1556 ± 1090 | 318 ± 168 |

| Boscolo et al. (Italy) [28] | ROTEM delta | 32 | ICU | 68 (62–75) | 26 M: 6 F | 3 (3–6) | NP | NP | NP | 1 (0–2) | 2 (2–2) | 29 (27–32) | NP | 110 (55–167) | 500 (450–570) | 315 (164–1326) | 283 (194–336) |

| 32 | IMW | 61 (53–71) | 24 M: 8 F | 2 (1–2) | NP | NP | NP | 0 (0–1.8) | 2 (1–2) | 29 (24–32) | 46 (16–96) | 450 (330–530) | 263 (193–598) | 234 (197–290) | |||

| Corrêa et al. (Brazil) [29] | ROTEM delta | 30 | ICU | 61 (52–83) | 15 M: 15 F | 10 (7–12) | NP | NP | 49 (41–61) | / | / | 29.3 (24.4–32.2) | Yes 10 | NP | 600 (480–680) | 1287 (798–2202) | 226 (176–261) |

| Madathil et al. (USA) [30] | ROTEM delta | 11 | ICU | 53 (45.5–65.5) | 7 M: 4 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28.1 (27.1–34.6) | Yes 11 | NP | NP | NP | NP |

| Spiezia et al. (Italy) [31] | ROTEM delta | 22 | ICU | 67 ± 8 | 20 M: 2 F | 4 ± 2 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 30 ± 6 | Yes 4 | NP | 517 ± 148 | 5343 ± 2099 | 240 ± 119 |

| Tsantes et al. (Greece) [32] | ROTEM delta | 11 | ICU COVID patients | 78 (67–71) | 10 M: 1 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 48 (23–128) | 439 (313–440) | 2420 (1470–7320) | 262 (120–350) |

| 9 | ICU non COVID patients | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | |||

| 21 | IMW COVID patients | 73 (50–88) | 11 M: 10 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 32 (9–55) | 437 (399–503) | 860 (540–1210) | 253 (207–396) | |||

| Al-Ghafry et al. (USA) [33] | ROTEM delta | 8 | PICU (n = 5) and PW (n = 3) | 12.9 (2–20) | 4 M: 4 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 21.9 (13.3–31.9) | NP | 86 (4–130) | 540 (329–732) | 932 (151–2451) | 258 (104–446) |

| Creel-Bulos et al. (USA) [34] | ROTEM delta | 25 | ICU | 63 (53–77) | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 276 (229–326) | NP | 7287 (4939–23,912) | NP |

| Hoechter et al. (Germany) [35] | ROTEM delta | 22 | ICU COVID+ (ROTEM n = 11) | 64 (52–70) | 19 M: 3 F | 11.5 (10.3–12) | NP | NP | NP | 1 (1–1) | NP | 27 (24–31) | Yes 4 | 156 (103–188) | 709 (530–786) | 2400 (2000–3900) | 227 (175–324) |

| 14 | ICU COVID- | 49 (36–57) | 9 M: 5 F | 15 (13.3–15) | NP | NP | NP | 3 (1–4) | NP | 26 (22–32) | NP | 274 (160–328) | 598 (502–645) | 11,300 (4100–31,000) | 175 (113–347) | ||

| Roh et al. (USA) [36] | ROTEM delta | 30 | ICU | 63 ± 12 | 15 M: 15 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 33 ± 8.1 | Yes 1 | NP | NP | 11,400 ± 7300 | 255 ± 103 |

| Kong et al. (United Kingdom) [37] | ROTEM delta | 1 | ICU | 48 | F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28.3 | Yes 1 | 196 | 840 | 510 | 307 |

| 1 | ICU | 68 | M | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 27.1 | Yes 4 | 336 | 680 | >20,000 | 126 | ||

| Raval et al. (USA) [38] | ROTEM delta | 1 | ICU | 63 | M | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 2143 | NP |

| Nougier et al. (France) [39] | Modified ROTEM delta (TEM-tPA) | 40 | ICU (ROTEM n = 19) | 62.8 ± 13.1 | NP | 5.4 ± 3.1 | NP | 37.9 ± 13 | NP | NP | NP | 29 ± 5.5 | NP | NP | 610 ± 190 | 3456 ± 2641 | NP |

| 38 | IMW (ROTEM n = 4) | 60.2 ± 14.6 | NP | / | / | / | / | / | / | 26.2 ± 4.8 | NP | 560 ± 170 | 874 ± 539 | NP | |||

| Weiss et al. (France) [40] | Modified ROTEM delta (TEM-tPA) | 5 | ICU | 57 ± 15 | 5 M: 0 F | 9 ± 2 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 740 ± 240 | 1975 ± 1623 | 440 ± 270 |

| Almskog et al. (Sweden) [41] | ROTEM sigma | 20 | ICU | 62 (55–66) | 12 M: 8 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28 (25–32) | Yes 5 | NP | 680 (480–760) | 1500 (700–4000) | 252 (206–341) |

| 40 | IMW | 61 (51–74) | 28 M: 12 F | / | / | / | / | / | / | 26 (24–32) | NP | 540 (430–650) | 600 (500–1000) | 212 (175–259) | |||

| Collett et al. (Australia) [42] | ROTEM sigma | 6 | ICU | 69 (64.2–73) | 5 M: 1 F | 7.5 (6.25–11.75) | 75.5 (65.75–105.5) | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 750 (721–808) | 6100 (2585–9660) | 291 (213–338) |

| Ibañez et al. (Spain) [43] | ROTEM sigma | 19 | ICU | 61 (55–73) | 10 M: 9 F | 4 (2–6) | NP | NP | NP | 1 (0–3) | 1.8 (0.9) | 28 (27–32) | Yes 10 | NP | 620 (480–760) | 1000 (600–4200) | 236 (136–364) |

| Kruse et al. (Germany) [44] | ROTEM sigma | 40 | ICU | 67 (57.3–76.6) | 35 M: 5 F | 9 (6.3–11.8) | 28 (22–33) | NP | NP | NP | 3 (2–4) | 28.1 (24.8–32.8) | Yes 10 | 124 (84–217) | 667 (470–770) | 3950 (2600–5900) | 194 (131–316) |

| Pavoni et al. (Italy) [45] | ROTEM sigma | 20 | ICU COVID-19 pneumonia | 60.3 ± 15.2 | 11 M: 9 F | 4.4 ± 0.8 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28.4 ± 4.7 | Yes 4 | NP | 698 ± 8 | 1364 ± 965 | 289 ± 155 |

| 25 | ICU non COVID-19 pneumonia | 66.5 ± 18.8 | 10 M: 15 F | 2.8 ± 1.1 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 25.2 ± 2.3 | NP | 349 ± 81 | 1476 ± 770 | 183 ± 70 | |||

| Spiezia et al. (Italy) [46] | ROTEM sigma | 56 | IMW COVID-19 pneumonia | 64 ± 15 | 37 M: 19 F | 2 ± 1 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 30 ± 4 | Yes 4 | 60 ± 56 | 451 ± 168 | 1079 ± 666 | 277 ± 131 |

| 56 | IMW non COVID-19 pneumonia | 76 ± 11 | 35 M: 21 F | 3 ± 1 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 27 ± 6 | 114 ± 77 | 488 ± 198 | 1296 ± 8 | 274 ± 89 | |||

| Van der Linden et al. (Sweden) [47] | ROTEM sigma | 12 | ICU before enhanced anticoagulation | 54 ± 9 | 12 M: 0 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 30.3 ± 5.6 | Yes 1 | 258 (135–348) | 870 ± 200 | 6900 (5700–10,000) | 393 ± 151 |

| 14 | ICU after enhanced anticoagulation | 59 ± 8 | 14 M: 0 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28.2 ± 4.2 | 57 (37–137) | 630 ± 250 | 3900 (2200–6800) | 320 ± 93 | |||

| Blasi et al. (Spain) [48] | ROTEM sigma | 12 | ICU | 69 (57–76) | 6 M: 6 F | 5.5 (3.3–7.8) | 15.5 (12–17.8) | NP | NP | NP | NP | 32 (27–35) | Yes 1 | 0.77 (0.42–2.59) | 393 (300–488) | 2535 (860–7848) | 196 (127–293) |

| 11 | IMW | 58 (42–74) | 8 M: 3 F | / | / | / | / | / | / | 29 (27–31) | 3.28 (2.33–8.96) | 502 (172–552) | 565 (425–2188) | 167 (154–239) | |||

| Van Veenendaal et al. (The Netherlands) [49] | ROTEM sigma | 47 | ICU | 63 (29–79) | 38 M: 9 F | / | / | 42 (17–70) | / | / | / | 28.8 (24.4–48.4) | Yes 4 | NP | 720 ± 160 | NP | 404 ± 154 |

| Lazar et al. (USA) [50] | ROTEM sigma | 1 | IMW | NP | NP | / | / | / | / | / | / | NP | NP | NP | 653 | 760 | NP |

| 1 | IMW | NP | NP | / | / | / | / | / | / | NP | NP | NP | 820 | 1330 | NP | ||

| Wright et al. (USA) [51] | TEG (NS) | 44 | ICU | 54 (42–59) | 28 M: 16 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 30 (27–37) | Yes 5 | NP | 656 (560–779) | 1840 (935–4085) | 232 (186–298) |

| Panigada et al. (Italy) [52] | TEG5000 | 24 | ICU | 56 (23–71) | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 161 (39–342) | 680 (234–1344) | 4877 (1197–16,954) | 348 (59–577) |

| Cordier et al. France) [53] | TEG5000 | 24 | ICU | 69 (61–71) | 16 M: 8 F | NP | NP | 45 (33–53) | NP | 3 (2–3) | NP | 28.5 (25.7–31) | NP | 128 (101–249) | 680 (620–790) | 3600 (1960–6490) | 220 (173–294) |

| Hightower et al. (USA) [54] | TEG5000 | 5 | ICU | 59 (38–69.5) | 3 M: 2 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 34.4 ± 3.9 | Yes 6 | NP | 658 ± 93 | 10,672 ± 7907 | 243 ± 35 |

| Maatman et al. (USA) [55] | TEG5000 | 109 | ICU (TEG n = 12) | 61 ± 16 | 62 M: 47 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 34.8 ± 11.8 | Yes 5 | 146 (101–227) | 535 (435–651) | 506 (321–973) | 207 (152–255) |

| Mortus et al. (USA) [56] | TEG5000 | 21 | ICU | 68 ± 11 | 12 M: 9 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | Yes (NS) | NP | 740 ± 240 | 8300 ± 7000 | 210 ± 100 |

| Sadd et al. (USA) [57] | TEG5000 | 10 | ICU | 58 (49–70) | 8 M: 2 F | 4 (3–5) | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 35 (30–39) | Yes 3 | 20 (13–25) | 676 (543–769) | 3150 (1000–6620) | 291 (224–408) |

| Yuriditsky et al. (USA) [58] | TEG5000 | 64 | ICU | 64 (57–71) | 46 M: 18 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | Yes 7 | 104 (35–158) | 669 (451–838) | 2374 (923–4820) | 244 (176–321) |

| Bocci et al. (Italy) [59] | TEG6s | 40 | ICU | 67.5 (55–77) | 29M: 11F | 5 ± 2.9 | NP | NP | NP | 2.9 ± 0.6 | NP | NP | Yes 8 | 160 (75–193) | 513 (304–605) | 1753 (699–4435) | 194 (163–281) |

| Stattin et al. (Sweden) [60] | TEG6s | 31 | ICU | 65 (51–70) | 25 M: 6 F | NP | NP | NP | 53 (48–60) | NP | NP | 30 (27–33) | Yes 5 | 214 (152–294) | NP | 2100 (900–3200) | 227 (163–248) |

| Vlot et al. (The Netherlands) [61] | TEG6s | 16 | ICU | 67 (56–73) | 12 M: 4 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | Yes 6 | NP | 620 (590–690) | 4425 (1870–5781) | 347 (302–462) |

| Patel et al. (United Kingdom) [62] | TEG6s | 39 | ICU | 52.5 (29–79) | 32 M: 7 F | 8 ± 2.5 | 18.7 ± 5 | NP | NP | NP | NP | 31.3 ± 6.1 | Yes 5 | 305 ± 101 | 660 ± 190 | 6440 ± 10,434 | 272 ± 77 |

| Salem et al. (United Arab Emirates) [63] | TEG6s | 52 | ICU | 53 (39–62) | 51 M: 1 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 25.8 (23–29.5) | Yes 9 | 50 (9–117) | 400 (270–600) | 4000 (3300–4000) | 228 (137–292) |

| Shah et al. (United Kingdom) [64] | TEG6s | 187 | ICU (TEG n = 20) | 57 (49–64) | 124 M: 63 F | NP | 13 (10–13) | NP | NP | NP | NP | 28 (25–32) | Yes 10 | 202 (128–294) | 700 (600–1000) | 2587 (950–10,000) | 241 (186–318) |

| Fan et al. (Singapore) [65] | TEG6s | 1 | IMW | 39 | M | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 136 | 770 | 2,55 | NP |

| Masi et al. (France) [66] | Quantra | 17 | ICU COVID+ | 48 (42–58) | 12 M: 5 F | 12 (9–17) | NP | 52 (43–63) | NP | 0 (0) | NP | 31 (28.8–40.5) | Yes 3 | 136 (92–315) | 710 (490–790) | 8390 (5330–11,180) | 231 (160–245) |

| 11 | ICU COVID- | 34 (28–55) | 7 M: 4 F | 9 (7–17) | NP | 57 (37–81) | NP | 4 (36) | NP | 29.3 (26–35) | NP | 320 (159–367) | 810 (640–945) | 4640 (3200–20,000) | 262 (224–334) | ||

| Ranucci et al. (Italy) [67] | Quantra | 16 | ICU | 61 (55–65) | 15 M: 1 F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 26.4 (23.9–35.1) | Yes 4 | NP | 794 (583–933) | 3500 (2500–6500) | 271 (192–302) |

| Bachler et al. (Austria) [24] | ClotPro | 20 | ICU | 61.5 (56.25–68) | 14 M: 6 F | 6.5 (3–8.25) | NP | NP | 56 (53–64) | NP | NP | 28.8 (24.3–31) | Yes 1 | 187.1 (116.4–275.7) | 600 (553–677.25) | 1554 (1227–9088) | 230 (202.5–297.25) |

| Zátroch et al. (Hungary) [68] | ClotPro | 1 | ICU | 62 | M | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | Yes 2 | 21 | NP | NP | NP |

| 1 | 80 | M | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 176–221 | 448 | 7370 | NP | ||||

| 1 | 84 | F | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 230–376 | 544 | 10,600 | NP |

| First Author (Country) | Design | n | Ward | Device | Controls | EXTEM | INTEM | FIBTEM | Conclusions of the Study | Association with the Occurrence of Thrombotic Events | Definition of Hypercoagulability Assessed by VET According to the Authors | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT (s) | CFT (s) | α Angle (°) | A(x) (mm) | MCF (mm) | ML (%) | LI30 (%) | LI60 (%) | CT (s) | CFT (s) | α Angle (°) | A(x) (mm) | MCF (mm) | ML (%) | CT (s) | CFT (s) | A(x) (mm) | MCF (mm) | ML (%) | LI30 (%) | LI60 (%) | |||||||||

| Iwasaki et al. (Japan) [26] | Case report | 1 | ICU (T1: D0) | NS | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | N | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | N | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | 100 | Hypercoagulable state not detected by conventional coagulation tests | NA | Increased MCF and decreased CFT |

| ICU (T2: D1) | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | N | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | N | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | 100 | ||||||||

| ICU (T3: D2) | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | N | N | N | NP | ↑ | ↑ | NP | N | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | NP | 100 | 100 | ||||||||

| Pavoni et al. (Italy) [27] | Retrospective observational study | 40 | ICU (T1: upon admission) | ROTEM gamma | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | N-↑ 1 | N-↓ 1 | NP | ↑ 1 | ↑ 1 | NP | NP | N1 | N1 | N-↓ 1 | NP | ↑ 1 | ↑ 1 | NP | NP | NP | NP | From ↑ to N 2 | NP | NP | NP | Inflammatory state associated with a hypercoagulable state rather than a consumption coagulopathy | NA | Increased MCF and decreased CFT |

| 40 | ICU (T2: 5 days later) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33/40 | ICU (T3: 10 days later) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boscolo et al. (Italy) [28] | Prospective observational study | 32 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range previously established in healthy adults | N | N | NP | NP | N | NP | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | N | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ 3 | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state assessed by an increased MCF in FIBTEM. No differences between patients with and without TE | No | Increased MCF |

| 32 | IMW | N | N | N | N | N | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Corrêa et al. (Brazil) [29] | Prospective observational study | 30 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | N-↑ | N | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state with increased MCF related to high fibrinogen levels | NA | Decreased CT and/or CFT in EXTEM and/or INTEM, and/or increased MCF in EXTEM, INTEM and/or FIBTEM |

| 16/30 | SOFA score < 10 | N-↑ | N | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| 14/30 | SOFA score > 10 | N-↑ | N | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | ↑ | ↓ | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| Madathil et al. (USA) [30] | Prospective observational study | 5/11 | D-dimers levels ≤ 3245 µg/L | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | N | NP | NP | N-↑ | NP | 0 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Critically ill COVID patients have significant elevation in D-dimers levels consistent with microthrombosis and an impaired systemic fibrinolysis | NA | NP |

| 6/11 | D-dimers levels > 3245 µg/L | N | NP | NP | N-↑ | NP | 0 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| Spiezia et al. (Italy) [31] | Prospective observational case control study | 22 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range previously established in healthy adults | N | ↓ | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | N | ↓ | NP | NP | ↑ | N | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state rather than a consumptive coagulopathy such as DIC, due to both increased levels of fibrinogen and excessive fibrin polymerization | NA | Increased MCF and decreased CFT |

| Tsantes et al. (Greece) [32] | Prospective observational study | 11 | ICU COVID-19 patients | ROTEM delta | Reference range previously established in healthy adults | N | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state and hypofibrinolytic profile with decreased CFT and ML, and increased aα angle, A10, MCF and LI60. More pronounced trend in ICU patients | NA | Increased clot amplitude (A(x) and/or MCF) |

| 9 | ICU non-COVID-19 patients | N | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| 21 | IMW COVID-19 patients | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| Al-Ghafry et al. (USA) [33] | Retrospective observational study | 8 | Pediatric COVID-19 patients (5 PICU, 3 PW) | ROTEM delta | Reference range according to age | 2/8 ↑ | 1/8 ↓ | NP | 2/8 ↑ | 4/8 ↑ | NP | NP | NP | 1/8 ↓ | 1/8 ↓ | NP | 2/8 ↑ | 3/8 ↑ | NP | NP | NP | 6/8 ↑ | 6/8 ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state comparable to adults. No correlation between MCF and Clauss fibrinogen nor D-dimers levels | No | Increased clot amplitude (A(x) and/or MCF) |

| Creel-Bulos et al. (USA) [34] | Retrospective observational study | 25 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | ↓ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Impaired fibrinolysis (fibrinolysis shutdown) is associated with a higher rate of TE | Yes | NP |

| Hoechter et al. (Germany) [35] | Retrospective observational case control study | 22 (ROTEM n = 11) | ICU COVID-19 patients | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | N | N | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | COVID-19 patients have higher coagulatory potential | No | NP |

| 14 | ICU non-COVID-19 patients | N | N | NP | NP | N | N | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | N | NP | NP | NP | |||||||

| Roh et al. (USA) [36] | Retrospective observational case control study | 30 | ICU COVID-19 ARDS patients | ROTEM delta | Surgical non COVID patients | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Critically-ill COVID-19 patients characterized by elevated D-dimers levels and hypercoagulable state related to increased fibrinogen. Negative correlation between D-dimers levels and ROTEM MCF | NA | Increased MCF two SD above normal healthy control testing |

| 30 | ICU surgical non-COVID-19 patients | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kong et al. (United Kingdom) [37] | Case report | 1 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | ↑ | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | N | NP | N | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | N | ↑ | ↑ | N | NP | ↑ | Hypercoagulable state with decreased CFT and increased MCF | NA | Increased MCF |

| 1 | ICU | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | N | N | ↓ | NP | ↑ | Hypocoagulable state with increased CFT and decreased MCF, with fibrinolysis shutdown as assessed by decreased ML%, increased LI60 and high level of D-dimers | ||||||

| Raval et al. (USA) [38] | Case report | 1 | ICU | ROTEM delta | Reference range as assessed by the manufacturer | NP | ↓ | ↑ | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | NP | ↑ | NP | NP | NP | Hypercoagulable state: VET as a possible screening tool for severe disease? | NA | Increased MCF and α angle, and decreased CFT |