The Impact of Pruritus on the Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Patients Suffering from Different Clinical Variants of Psoriasis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Studied Population

2.3. Psychometric and Clinical Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

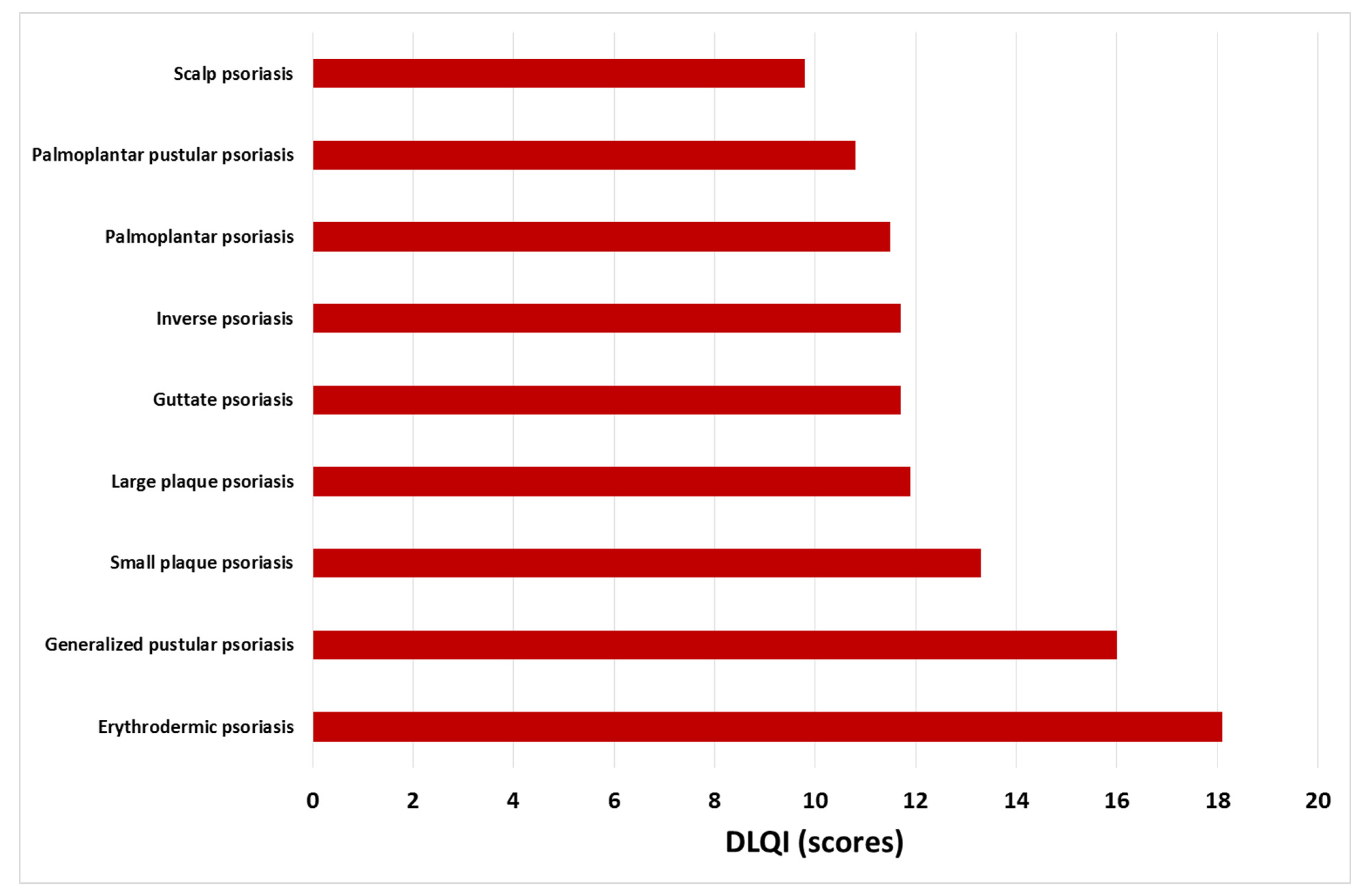

3.1. Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Psoriasis

3.2. Factors Influencing Quality of Life

3.3. Relationship between Pruritus and Sleep Disturbance

3.4. Correlation between Severity of Pruritus and Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Different Clinical Subtypes of Psoriasis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H. Quality of life in palliative care: Principles and practice. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.E.; Cohen, J.M.; Ho, R.S. Psoriasis and suicidality: A review of the literature. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picardi, A.; Abeni, D. Stressful life events and skin diseases: Disentangling evidence from myth. Psychother. Psychosom. 2001, 70, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J. Insomnia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 309, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawro, T.; Hawro, M.; Zalewska-Janowska, A.; Weller, K.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M. Pruritus and sleep disturbances in patients with psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2020, 312, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, E.; Hawro, M.; Weller, K.; Sabat, R.; Philipp, S.; Kokolakis, G.; Christou, D.; Metz, M.; Maurer, M.; Hawro, T. Prevalence and factors associated with sleep disturbance in adult patients with psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.A.; Simpson, F.C.; Gupta, A.K. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 29, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepietowski, J.C.; Reich, A. Pruritus in psoriasis: An update. Eur. J. Pain 2016, 20, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworecka, K.; Kwiatkowska, D.; Marek, L.; Tamer, F.; Stefaniak, A.; Szczegielniak, M.; Chojnacka-Purpurowicz, J.; Matławska, M.; Gulekon, A.; Szepietowski, J.C.; et al. Characteristics of pruritus in various clinical variants of psoriasis: Results of the multinational, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Life 2021, 11, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawro, M.; Sahin, E.; Steć, M.; Różewicka-Czabańska, M.; Raducha, E.; Garanyan, L.; Philipp, S.; Kokolakis, G.; Christou, D.; Kolkhir, P.; et al. A comprehensive, tri-national, cross-sectional analysis of characteristics and impact of pruritus in psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.; Christophers, E.; Barker, J.N.; Chalmers, R.J.; Chimenti, S.; Krueger, G.G.; Leonardi, C.; Menter, A.; Ortonne, J.P.; Fry, L. A classification of psoriasis vulgaris according to phenotype. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, S.P.; Lebwohl, M.; Kahler, K.N. Development of the US PSORIQoL: A psoriasis-specific measure of quality of life. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, A.Y.; Khan, G.K. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1994, 19, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basra, M.K.; Fenech, R.; Gatt, R.M.; Salek, M.S.; Finlay, A.Y. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994-2007: A comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 997–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimball, A.B.; Naegeli, A.N.; Edson-Heredia, E.; Lin, C.Y.; Gaich, C.; Nikaï, E.; Wyrwich, K.; Yosipovitch, G. Psychometric properties of the Itch Numeric Rating Scale in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, A.; Reich, A. Validity assessment of the 10-Item Pruritus Severity Scale. Forum Dermatol. 2018, 4, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bożek, A.; Reich, A. The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: Psoriasis area and severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, A.; Reich, A. How to reliably evaluate the severity of psoriasis? Forum Dermatol. 2016, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, M.; Burden, A.D.; McElhone, K.; James, R.; Vanhoutte, F.P.; Griffiths, C.E.M. Oral liarozole in the treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 145, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, A.; Yamazaki, F.; Matsuyama, T.; Takahashi, K.; Arai, S.; Asahina, A.; Imafuku, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Williams, D.; et al. Adalimumab treatment in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: Results of an open-label phase 3 study. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkalová, J.; Borská, L.; Hamáková, K.; Hodačová, L.; Čermáková, E.; Fiala, Z. Quality of life of patients with psoriasis. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, M.; Radtke, M.A. Quality of life in psoriasis patients. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2014, 14, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, K.H. What factors influence on dermatology-related life quality of psoriasis patients in South Korea? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J.M.; Rathore, M.U.; Tahir, M.; Abbasi, T. Dermatology Life Quality Index in patients of psoriasis and its correlation with severity of disease. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2020, 32, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, B.P.; Alexis, A.F. Psoriasis in skin of color: Insights into the epidemiology; clinical presentation; genetics; quality-of-life impact; and treatment of psoriasis in non-white racial/ethnic groups. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsabal, M.; Ly, S.; Sbidian, E.; Moyal-Barracco, M.; Dauendorffer, J.N.; Dupin, N.; Richard, M.A.; Chosidow, O.; Beylot-Barry, M. GENIPSO: A French prospective study assessing instantaneous prevalence; clinical features and impact on quality of life of genital psoriasis among patients consulting for psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 180, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowietz, U.; Chouela, E.N.; Mallbris, L.; Stefanidis, D.; Marino, V.; Pedersen, R.; Boggs, R.L. Pruritus and quality of life in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: Post hoc explorative analysis from the PRISTINE study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, H.S.; Ko, H.C.; Kim, M.B.; Kim, B.S. Characteristics of pruritus according to morphological phenotype of psoriasis and association with neuropeptides and interleukin-31. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.; Welz-Kubiak, K.; Rams, Ł. Apprehension of the disease by patients suffering from psoriasis. Post. Dermatol. Alergol. 2014, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Goon, A.; Wee, J.; Chan, Y.H.; Goh, C.L. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pruritus among patients with extensive psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 143, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, K.; Steuden, S.; Bogaczewicz, J. Clinical and psychological characteristics of patients with psoriasis reporting various frequencies of pruritus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amatya, B.; Wennersten, G.; Nordlind, K. Patients’ perspective of pruritus in chronic plaque psoriasis: A questionnaire-based study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.; Zachariae, C.; Skov, L.; Zachariae, R. Sleep disturbance in psoriasis: A case-controlled study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. Athens Insomnia Scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 48, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J.; Junghanns, K.; Broocks, A.; Riemann, D.; Hohagen, F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepietowski, J.C.; Reich, A.; Wiśnicka, B. Itching in patients suffering from psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2002, 10, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chrostowska-Plak, D.; Reich, A.; Szepietowski, J.C. Relationship between itch and psychological status of patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, e239–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, F.; Faffa, M.S.; Poizeau, F.; Merhand, S.; Misery, L.; Brenaut, E. Characteristics of pruritus in relation to self-assessed severity of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pérez, J.; Daudén-Tello, E.; Mora, A.M.; Lara Surinyac, N. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life in Spanish children and adults: The PSEDA study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013, 104, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Subjects (%) | Gender Female (%)/Male (%) | Age Min–Max (Mean ± SD) | BMI Min–Max (Mean ± SD) | Age at Disease Onset Min–Max (Mean ± SD) | Coexisting Psoriatic Arthritis (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 295 (100) | 148 (50.2)/147 (49.8) | 16–77 (45.0 ± 15.3) | 14.5–46.0 (27.5 ± 5.6) | 2–76 (32.9 ± 16.8) | 27 (9.2) |

| Large plaque psoriasis | 45 (15.3) | 15 (33.3) 30 (66.7) | 17–77 (46.7 ± 15.9) | 21.4–42.8 (30.2 ± 5.5) p < 0.001 * | 6–72 (30.3 ± 17.5) | 5 (11.1) |

| Small plaque psoriasis | 32 (10.8) | 11 (34,4) 21 (65.6) | 16–69 (40.6 ± 13.6) | 14.5–37.6 (26.4 ± 5.3) | 3–58 (27.3 ± 15.1) | 2 (6.3) |

| Guttate psoriasis | 31 (10.5) | 14 (45.2) 17 (54.8) | 17–73 (37.5 ± 11.6) | 19.5–46.0 (27.5 ± 6.4) | 7–53 (24.0 ± 12.1) | 4 (12.9) |

| Palmoplantar psoriasis | 33 (11.2) | 18 (54.6) 15 (45.4) | 16–71 (45.3 ± 14.9) | 18.1–43.4 (28.3 ± 5.7) | 10–69 (36.1 ± 16.5) | 2 (6.1) |

| Scalp psoriasis | 32 (10.8) | 19 (59.4) 13 (40.6) | 16–61 (34.9 ± 12.4) | 15.4–34.1 (24.2 ± 4.4) p < 0.001 * | 6–50 (23.7 ± 11.7) | 2 (6.3) |

| Inverse psoriasis | 23 (7.8) | 12 (52.2) 11 (47.8) | 18–67 (41.5 ± 14.0) | 18.8–41.5 (29.3 ± 5.6) | 13–60 (30.7 ± 14.2) | 2 (8.7) |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis | 33 (11.2) | 9 (27.3) 24 (72.7) | 18–71 (47.5 ± 16.6) | 17.6–44.5 (27.8 ± 6.4) | 3–60 (31.9 ± 16.7) | 5 (15.2) |

| Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis | 43 (14.6) | 37 (86.1) 6 (13.9) | 28–77 (53.8 ± 12.6) p < 0.001 * | 18.8–37.2 (26.4 ± 4.5) | 16–69 (45.7 ± 12.1) p < 0.001 * | 1 (2.3) |

| Generalized pustular psoriasis | 23 (7.8) | 13 (56.5) 10 (43.5) | 28–76 (54.9 ± 14.3) p < 0.001 * | 17.2–39.3 (27.0 ± 4.8) | 2–76 (45.5 ± 19.1) p < 0.001 * | 4 (17.4) |

| DLQI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | p | |

| PASI | 209 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| BSA | 281 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| sPGA | 293 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| GPPSI | 23 | 0.34 | 0.12 |

| PPSI | 42 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| NRSmax | 274 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| NRSaverage | 274 | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| 10-PSS | 263 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| n | Mean DLQI Scoring | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problems in falling asleep | Almost always | 67 | 17.3 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 115 | 13.5 ± 7.0 | ||

| Never | 111 | 9.0 ± 7.5 | ||

| Awakenings during the night | Almost every night | 60 | 17.4 ± 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 98 | 13.9 ± 7.5 | ||

| Never | 135 | 9.7 ± 7.2 | ||

| Use of sleeping medication | Almost every day | 10 | 18.4 ± 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 51 | 15.5 ± 7.0 | ||

| Never | 232 | 11.8 ± 7.9 | ||

| Mean NRSmax | p | Mean NRSaverage | p | Mean 10-PSS | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problems in falling asleep | Almost always | 7.3 ± 2.2 | <0.001 | 6.0 ± 2.5 | <0.001 | 13.5 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 9.4 ± 3.1 | ||||

| Never | 3.3 ± 2.7 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 5.8 ± 3.8 | ||||

| Awakenings during the night | Almost every night | 7.3 ± 2.3 | <0.001 | 6.1 ± 2.6 | <0.001 | 13.3 ± 3.4 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 5.6 ± 2.3 | 4.2 ± 2.2 | 9.7 ± 3.6 | ||||

| Never | 3.8 ± 2.7 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 6.5 ± 3.9 | ||||

| Use of sleeping medication | Almost every day | 8.2 ± 1.7 | <0.001 | 7.4 ± 2.5 | <0.001 | 15.1 ± 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Rarely | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 10.7 ± 3.5 | ||||

| Never | 4.7 ± 2.8 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 8.3 ± 4.5 | ||||

| Large-Plaque Psoriasis | Small- Plaque Psoriasis | Guttate Psoriasis | Palmo-Plantar Psoriasis | Psoriasis of the Scalp | Inverse Psoriasis | Erythrodermic Psoriasis | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Generalized Pustular Psoriasis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLQI vs. | NRSaverage | ρ = 0.51, p < 0.001 | ρ = 0.17, p = 0.37 | ρ = 0.18, p = 0.35 | ρ = 0.27, p = 0.12 | ρ =0.52, p = 0.003 | ρ = 0.17, p = 0.44 | ρ = 0.15, p = 0.41 | ρ = 0.43, p = 0.004 | ρ = 0.48, p = 0.02 |

| NRSmax | ρ = 0.56, p < 0.001 | ρ = 0.07, p = 0.71 | ρ = 0.3 p = 0.11 | ρ = 0.29, p = 0.11 | ρ = 0.43, p = 0.01 | ρ = 0.42, p < 0.05 | ρ = 0.25, p = 0.15 | ρ = 0.53, p < 0.001 | ρ = 0.34, p = 0.11 | |

| 10-PSS | ρ = 0.16, p = 0.29 | ρ = 0.14, p = 0.43 | ρ = 0.54, p = 0.002 | ρ = 0.51, p = 0.003 | ρ = 0.64, p < 0.001 | ρ = 0.38, p = 0.08 | ρ = 0.18, p = 0.32 | ρ = 0.56, p < 0.001 | ρ = 0.41, p < 0.05 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaworecka, K.; Rzepko, M.; Marek-Józefowicz, L.; Tamer, F.; Stefaniak, A.A.; Szczegielniak, M.; Chojnacka-Purpurowicz, J.; Gulekon, A.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Narbutt, J.; et al. The Impact of Pruritus on the Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Patients Suffering from Different Clinical Variants of Psoriasis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195553

Jaworecka K, Rzepko M, Marek-Józefowicz L, Tamer F, Stefaniak AA, Szczegielniak M, Chojnacka-Purpurowicz J, Gulekon A, Szepietowski JC, Narbutt J, et al. The Impact of Pruritus on the Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Patients Suffering from Different Clinical Variants of Psoriasis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(19):5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195553

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaworecka, Kamila, Marian Rzepko, Luiza Marek-Józefowicz, Funda Tamer, Aleksandra A. Stefaniak, Magdalena Szczegielniak, Joanna Chojnacka-Purpurowicz, Ayla Gulekon, Jacek C. Szepietowski, Joanna Narbutt, and et al. 2022. "The Impact of Pruritus on the Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Patients Suffering from Different Clinical Variants of Psoriasis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 19: 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195553

APA StyleJaworecka, K., Rzepko, M., Marek-Józefowicz, L., Tamer, F., Stefaniak, A. A., Szczegielniak, M., Chojnacka-Purpurowicz, J., Gulekon, A., Szepietowski, J. C., Narbutt, J., Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A., & Reich, A. (2022). The Impact of Pruritus on the Quality of Life and Sleep Disturbances in Patients Suffering from Different Clinical Variants of Psoriasis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(19), 5553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195553