Dreaming in Parasomnias: REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

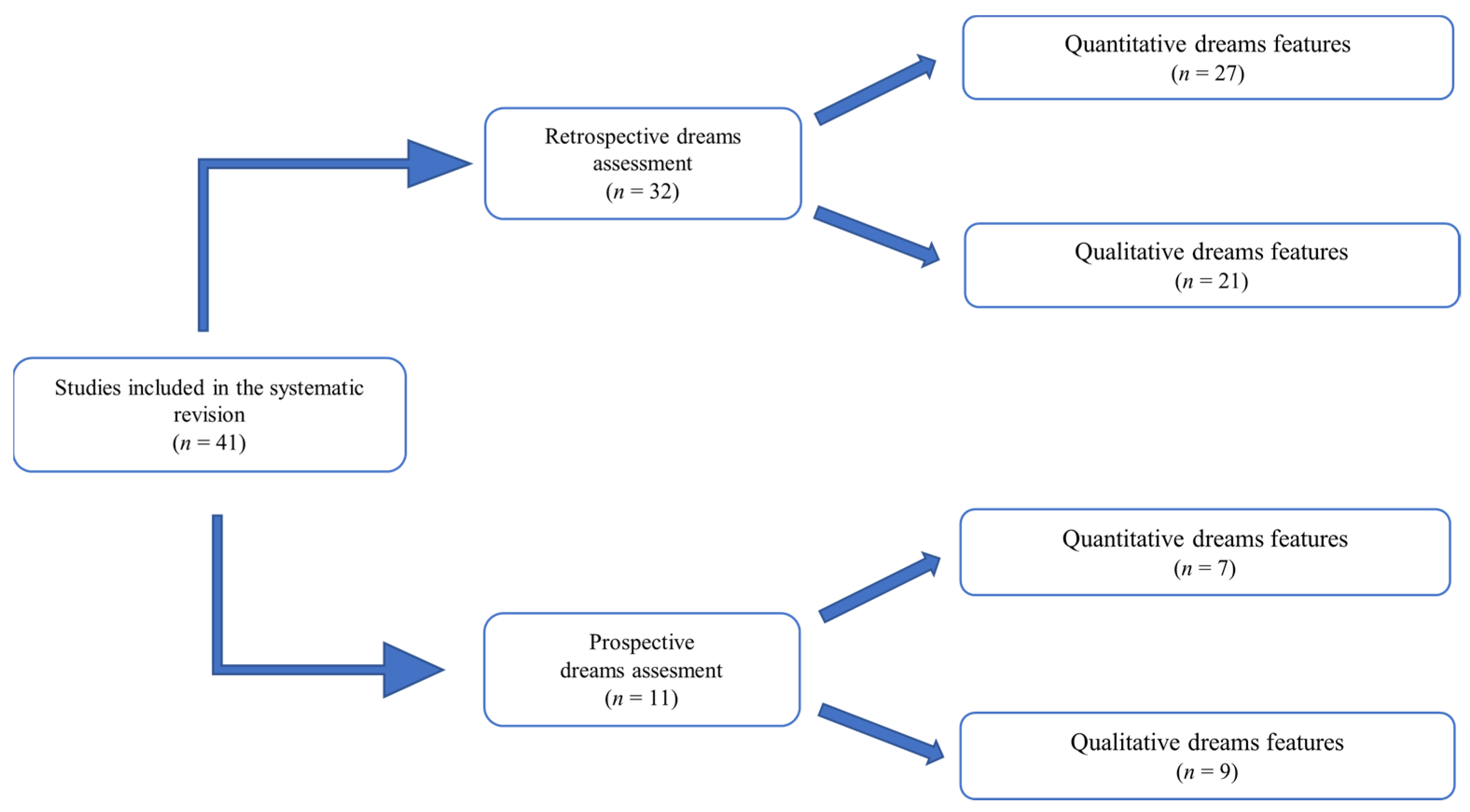

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. How RBD Patients Dream?

| Study | RBD Sample | HC Sample | Design | Dream Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | 39 RBD < 50 y Mean age (SD): 32 ± 9 y Gender: 23 M/16 F 52 RBD ≥ 50 y Mean age (SD): 67 ± 8 y Gender: 39 M/13 F | X | Cross-Sectional | Not specified | Dream Content:

|

| [12] | 20 early onset RBD Gender: 12 M/11 F 67 late-onset RBD Gender: 51 M/16 F | 90 HC Gender: 63 M/27 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-HK | DRF: In total, 91% RBD reported dreams more than 3 times per week Dream-related scores (Factor1):

|

| [44] | 4 iRBD Gender: 2 M/2 F | X | Cross-Sectional Descriptive | Not specified | Dream content:

|

| [13] | 93 RBD Mean age: 64.4 y Gender: 81 M/12 F | X | Retrospective Descriptive Case Series | Not specified | Dream Report (n 67):

|

| [14] | 203 iRBD Gender: 162 M/41 F | X | Longitudinal Descriptive | Semi-structured interview | Unpleasant dream recall:

|

| [15] | 7 RBD Gender: 5 M/2 F | X | Cross-Sectional Descriptive | Telephone interview | All RBD patients reported violent dreams |

| [45] | 56 RBD Mean age (SD): 64.7 ± 8.2 y Gender: 43 M/13 F | 17 HC Mean age (SD): 62.2 ± 7.1 y Gender: 14 M/3 F | Cross-Sectional Descriptive | Immediate dream recall through interview | Detailed dream reports examples in the paper: |

| [16] | 49 RBD Mean age (SD): 67.5 ± 7.5 y Gender: 36 M/5 F | 35 HC Mean age (SD): 69.1 ± 5.9 y Gender: 30 M/5 F | Cross-Sectional | Free recall and semi-structured interview scored by HVdC | DRF: >in RBD (p < 0.001) Dream content

|

| [18] | 94 RBD Mean age (SD): 61.9 ± 12.7 y Gender: 66 M/28 F | X | Cross-Sectional | Clinical interview | DRF:

|

| [19] | 141 M iRBD Mean age (SD): 66.7 ± 6.7 y 43 F iRBD Mean age (SD): 68.7 ± 7.3 y | X | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-JP | Dream-related scores (Factor1): Absence of significant difference between male and female iRBD |

| [20] | 90 RBD Gender: 63 M/27 F | X | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-HK | Dream-related scores (Factor1): Absence of significant difference between M and F RBD Vivid dreams: Absence of significant differences between M and F RBD Violent dreams: Absence of significant differences between M and F RBD Frightening dreams: Absence of significant differences between M and F RBD |

| [21] | 68 RBD Mean age (SD): 63.7 ± 10.9 y Gender: 49 M/19 F | 44 HC Mean age (SD): 62.0 ± 12.2 y Gender: 28 M/16 F | Cross-Sectional | TDQ DTD index | DRF:

|

| [22] | 8 non-recallers RBD Age range: 69.8–75.8 y Gender: 6 M/2 F 17 recallers RBD Age range: 66.0–75.0 y Gender: 12 M/5 F | X | Cross-sectional | Dream interview | DRF:

|

| [23] | 53 RBD Mean age (SD): 69.0 ± 16.5 y Gender: 39 M/14 F | X | Cross-Sectional Descriptive | Dream questionnaire | DRF: >in RBDs in which injury occurred compared to RBDs in which injury did not occur (p = 0.002) Dream content:

|

| [24] | 6 RBD Mean age: 54 y Gender: 3 M/3 F | X | Longitudinal (6 weeks) to examine the effect of melatonin treatment | Modification in dream activity after treatment | None of the responders reported any frightening dreams during the treatment period |

| [25] | 8 RBD Mean age: 54 y Gender: 8 M | X | Longitudinal (4 weeks) to examine the effect of melatonin treatment | Modification in dream activity after treatment | Dream Content: None of the responders reported having frightening dreams after four days of treatment DRF: All patients were able to distinguish placebo from treatment based on a reduction in dream mentation |

| [26] | 39 RBD Mean age (SD): 68.3 ± 7.8 y Gender: 29 M/10 F | X | Longitudinal (28.8 months) to examine the effect of clonazepam treatment | RBDQ-3M | DRF: Absence of significant differences pre/post-treatment Nightmare frequency: >before than pre-treatment (p < 0.01) Dream-related scores (Factor 1):

|

| [27] | 32 RBD Mean age (SD): 61.5 ± 11.1 y Gender: 23 M/9 F | 30 HC Mean age (SD): 56.9 ± 16.6 y Gender: 19 M/11 F | Cross-Sectional | Dream questionnaire |

|

| [29] | 29 iRBD Mean age (SD): 62.9 ± 9.4 y Gender: 23 M/8 F 31 pRBD Mean age (SD): 44.4 ± 9.8 y Gender: 13 M/8 F | 31 HC Mean age (SD): 46.0 ± 12.5 y Gender: 11 M/20 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-HK | Dream-related scores (Factor1):

|

| [30] | 51 iRBD Gender: 41 M/10 F 29 sRBD Gender: 23 M/6 F 27 RBD like Gender: 11 M/16 F | 107 HC Mean age (SD): 55.3 ± 9 y Gender: 62 M/45 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-HK | Dream-related scores (Factor1):

|

| [31] | 105 RBD Mean age (SD): 67.3 ± 6.4 y Gender: 60 M/49 F | 105 HC Mean age (SD): 65.8 ± 5.7 y Gender: 49 M/56 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-KR | Dream related scores (Factor1): >in RBD compared to HC (p < 0.001) |

| [32] | 13 iRBD Mean age (SD): 66.3 ± 6.5 y Gender: 11 M/2 F | 10 HC Mean age (SD): 62.3 ± 7.5 y Gender: 7 M/3 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-KR | Dream-related scores (Factor1):

|

| [33] | 94 RBD Mean age (SD): 67.6 ± 7.3 y Gender: 53 M/41 F | 50 HC Mean age (SD): 65.4 ± 6.0 y Gender: 24 M/26 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ-KR | Dream related scores (Factor1): >in RBD than HC (p < 0.001) Correlations:

|

| [48] | 12 RBD Mean age (SD): 65.6 ± 10.7 y Gender: 11 M/1 F | 12 HC Mean age (SD): 63.3 ± 12.9 y Gender: 8 M/4 F | Cross-Sectional | Dream diary (3 weeks) | Dream content:

Words number: Absence of significant difference between RBD and HC |

| [49] | 13 clonazepam-treated iRBD Mean age (SD): 65.3 ± 10.9 y Gender: 12 M/1 F 11 untreated iRBD Mean age (SD): 68.9 ± 6.8 y Gender: 9 M/2 F | 12 HC Mean age (SD): 63.3 ± 12.8 y Gender: 8 M/4 F | Cross-Sectional | Dream diary (3 weeks) scored by HVdC TSS | Dream Reports (n 214):

|

| [34] | 123 RBD divided in 96 with treatment- improvement Mean age (SD): 65.7 ± 8.5 y Gender: 61 M/35 F 27 without treatment- improvement Mean age (SD): 66.1 ± 7.5 y Gender: 15 M/12 F | X | Longitudinal (17.7 months) to examine the effect of clonazepam treatment | RBDQ-KR | Dream-related scores (Factor1): Absence of significant difference between responding and no-respond groups |

3.2. Dreaming in RBD: A Window into Neurodegenerative Mechanisms?

| Study | Sample | Design | Dream Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | 49 PD + RBD Mean age (SD): 68.3 ± 7.5 y Gender: 33 M/16 F 36 PD—RBD Mean age (SD): 69.9 ± 9.6 y Gender: 18 M/18 F 30 HC Mean age (SD): 66.8 ± 9.9 y Gender: 12 M/18 F | Cross-Sectional | Dream Diary (1 month) scored by HVdC | Total dreams collected: 106 DRF

|

| [50] | 65 PD + RBD Mean age (SD): 65 ± 9 y Gender: 44 M/21 F 35 PD—RBD Mean age (SD): 61 ± 13 y Gender: 21 M/14 F | Cross-Sectional | Interview | Dream Content in PD + RBD

|

| [51] | 6 PD + RBD Mean age (SD): 58.5 ± 8.4 y | Multiple Awakenings | Dream Questionnaire | DRF

|

| [52] | 9 PD + RBD 1 PD 3 HC | Cross-sectional Descriptive | Immediate Free Dream Recall |

|

| [35] | 36 PD + RBD Mean age (SD): 67.2 ± 7.3 y Gender: 25 M/11 F 26 PD—RBD Mean age (SD): 68.3 ± 10 y Gender: 18 M/8 F 24 PD + probable RBD | Cross-Sectional | NMSQuest—Item 24 |

|

| [36] | 9 PD + RBD Mean age (SD): 61.2 ± 9.8 y Gender: 7 M/2 F 8 PD—RBD Mean age (SD): 64.0 ± 10.3 y Gender: 6 M/2 F | Multiple Awakenings | Semi-Structured Interview Immediate Dream Recall | DRF changes after the PD onset

Awakenings

|

| [37] | 13 DLB Mean age (SD): 78.4 ± 6.2 y Gender: 6 M/7 F 13 DLB + RBD Mean age (SD): 77.4 ± 5.7 y Gender: 10 M/3 F | Cross-Sectional Descriptive | Clinical Interview | Unpleasant dream recall: 7 of the 13 (53.8%) patients with DLB + RBD |

3.3. Dream Features in RBD and NREM Parasomnias or Other Sleep Disorders

| Study | Sample | Design | Dream Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 24 RBD Mean age (SD): 68.6 ± 8.8 y Gender: 19 M/5 F 32 SW/ST Mean age (SD): 31.4 ± 8.4 y Gender: 16 M/16 F | Cross-sectional | Immediate free dream recall scored by HVdC TSS Dream complexity | No. of dreams:

Complexity:

|

| [28] | 64 RBD Mean age (SD): 68.6 ± 8.0 y Gender: 44 M/20 F 62 SW Mean age (SD): 31.7 ± 9.5 y Gender: 29 M/33 F 66 oHC Mean age (SD): 67 ± 7.8 y Gender: 43 M/23 F 59 yHC Mean age (SD): 31.9 ± 9.3 y Gender: 29 M/30 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDSQ |

|

| [47] | 20 RBD Mean age (SD): 66.5 ± 6.5 y Gender: 16 M/4 F 19 SW Mean age (SD): 34.4 ± 15.4 y Gender: 6 M/13 F 18 HC Mean age (SD): 57.9 ± 5.3 y Gender: 14 M/4 F | Cross-Sectional | Immediate free recall | DRF: absence of significant between-group differences |

| [39] | 16 iRBD Mean age (SD): 64.5 ± 5.1 y Gender: 13 M/3 F 16 OSA Mean age (SD): 59.6 ± 7.7 y Gender: 11 M/5 F 20 HC Mean age (SD): 63.0 ± 9.8 y Gender: 16 M/4 F | Cross-Sectional | Not specified | Unpleasant dream content:

|

| [62] | 118 RBD Mean age (SD): 66.5 ± 8.4 y Gender: 91 M/27 F 106 OSA Mean age (SD): 61.6 ± 8.4 y Gender: 57 M/49 F | Cross-Sectional | RBDQ—Beijing | Dream related scores (Factor 1): >in RBD compared to OSA (p < 0.001) |

| [6] | 15 RBD + PTSD Mean age: 55.2 y 12 RBD Mean age: 57.6 y 7 PTSD Mean age: 56.7 y | Cross-Sectional | Not specified | Dream content/emotions:

|

3.4. RBD in Infants

| Study | Sample | Design | Dream Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | 15 RBD Mean age: 9.5 y Gender: 11 M/15 F | Retrospective Descriptive Case Series | Not specified | Dream Content

|

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sateia, M.J. International classification of sleep disorders. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schredl, M.; Wittmann, L. Dreaming: A psychological view. Dreaming 2004, 484, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonsi, V.; D’Atri, A.; Scarpelli, S.; Mangiaruga, A.; De Gennaro, L. Sleep talking: A viable access to mental processes during sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 44, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, M.W. REM sleep behavior disorder: Clinical, developmental, and neuroscience perspectives 16 years after its formal identification in SLEEP. Sleep 2002, 25, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, A.; Verga, L.; Giora, E.; Zucconi, M.; Ferini-Strambi, L. The risk of neurodegeneration in REM sleep behavior disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 43, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferini-Strambi, L.; Fasiello, E.; Sforza, M.; Salsone, M.; Galbiati, A. Neuropsychological, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging biomarkers for REM behavior disorder. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 1069–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gennaro, L.; Lanteri, O.; Piras, F.; Scarpelli, S.; Assogna, F.; Ferrara, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Spalletta, G. Dopaminergic system and dream recall: An MRI study in Parkinson’s disease patients. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 1136–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, L.L.; Kohn, R.; Friedman, J.H. Phenomenology of dreams in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.; Tippmann-Peikert, M.; Slocumb, N.; Kotagal, S. Characteristics of REM sleep behavior disorder in childhood. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postuma, R.B.; Gagnon, J.F.; Vendette, M.; Fantini, M.L.; Massicotte-Marquez, J.; Montplaisir, J. Quantifying the risk of neurodegenerative disease in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2009, 72, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonakis, A.; Howard, R.S.; Ebrahim, I.O.; Merritt, S.; Williams, A. REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) and its associations in young patients. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Lei, F.; Wing, Y.K.; Kushida, C.A.; Zhou, D.; Tang, X. Characteristics of early-and late-onset rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in China: A case–control study. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.J.; Boeve, B.F.; Silber, M.H. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: Demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in 93 cases. Brain 2000, 123, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Arcos, A.; Iranzo, A.; Serradell, M.; Gaig, C.; Santamaria, J. The clinical phenotype of idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder at presentation: A study in 203 consecutive patients. Sleep 2016, 39, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Yoon, I.Y.; Lee, S.D.; Han, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, K.W. REM sleep behavior disorder in the Korean elderly population: Prevalence and clinical characteristics. Sleep 2013, 36, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, M.L.; Corona, A.; Clerici, S.; Ferini-Strambi, L. Aggressive dream content without daytime aggressiveness in REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2005, 65, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uguccioni, G.; Golmard, J.L.; de Fontréaux, A.N.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Brion, A.; Arnulf, I. Fight or flight? Dream content during sleepwalking/sleep terrors vs. rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.G.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Jeong, D.U. Depressed REM sleep behavior disorder patients are less likely to recall enacted dreams than non-depressed ones. Psychiatry Investig. 2016, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, N.; Sasai-Sakuma, T.; Inoue, Y. Gender differences in clinical findings and α-synucleiopathy-related markers in patients with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2020, 66, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Du, L.; Li, Z.; Lei, F.; Wing, Y.K.; Kushida, C.A.; Zhou, D.; Tang, X. Gender differences in REM sleep behavior disorder: A clinical and polysomnographic study in China. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, I.; Montplaisir, J.; Nielsen, T. Dreaming and nightmares in REM sleep behavior disorder. Dreaming 2015, 25, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlin, B.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Chaumereuil, C.; Arnulf, I. Evidence that non-dreamers do dream: A REM sleep behaviour disorder model. J. Sleep Res. 2015, 24, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter, S.J.; Louis, E.K.S.; Boswell, C.L.; Dueffert, L.G.; Slocumb, N.; Boeve, B.F.; Silber, M.H.; Olson, E.J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Tippmann-Peikert, M. Factors associated with injury in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, D.; Bes, F. Melatonin as a therapy in REM sleep behavior disorder patients: An open-labeled pilot study on the possible influence of melatonin on REM-sleep regulation. Mov. Disord. 1999, 14, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, D.; Mahlberg, R. A two-part, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of exogenous melatonin in REM sleep behaviour disorder. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Lam, S.P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.W.M.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Liu, Y.; Lam, V.K.H.; Ho, C.K.W.; Zhou, J.; Wing, Y.K. A prospective, naturalistic follow-up study of treatment outcomes with clonazepam in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2016, 21, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, I.; Montplaisir, J.; Gagnon, J.F.; Nielsen, T. Alexithymia associated with nightmare distress in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2013, 36, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridi, M.; Weyn Banningh, S.; Clé, M.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Vidailhet, M.; Arnulf, I. Is there a common motor dysregulation in sleepwalking and REM sleep behaviour disorder? J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 614–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.P.; Li, S.X.; Chan, J.W.; Mok, V.; Tsoh, J.; Chan, A.; Yu, M.W.M.; Lau, C.Y.; Zhang, J.; Lam, V.; et al. Does rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder exist in psychiatric populations? A clinical and polysomnographic case–control study. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Wing, Y.K.; Lam, S.P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.W.M.; Ho, C.K.W.; Tsoh, J.; Mok, V. Validation of a new REM sleep behavior disorder questionnaire (RBDQ-HK). Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Moon, H.J.; Do, S.Y.; Wing, Y.K.; Sunwoo, J.S.; Jung, K.Y.; Cho, Y.W. The REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire: Validation study of the Korean version (RBDQ-KR). J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunwoo, J.S.; Cha, K.S.; Byun, J.I.; Kim, T.J.; Jun, J.S.; Lim, J.A.; Lee, S.T.; Jung, K.H.; Park, K.I.; Chu, K.; et al. Abnormal activation of motor cortical network during phasic REM sleep in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2019, 42, zsy227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, J.S.; Kim, R.; Jung, H.M.; Byun, J.I.; Seok, J.M.; Kim, T.J.; Lim, J.A.; Sunwoo, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Schenck, C.H.; et al. Emotion dysregulation in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2020, 43, zsz224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunwoo, J.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Byun, J.I.; Kim, T.J.; Jun, J.S.; Lee, S.T.; Jung, K.H.; Park, K.I.; Chu, K.; Kim, M. Comorbid depression is associated with a negative treatment response in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. J. Clin. Neurol. 2020, 16, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neikrug, A.B.; Avanzino, J.A.; Liu, L.; Maglione, J.E.; Natarajan, L.; Corey-Bloom, J.; Palmer, B.W.; Loredo, J.S.; Ancoli-Israel, S. Parkinson’s disease and REM sleep behavior disorder result in increased non-motor symptoms. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, K.; Frauscher, B.; Peltomaa, T.; Gschliesser, V.; Revonsuo, A.; Högl, B. Dreaming furiously? A sleep laboratory study on the dream content of people with Parkinson’s disease and with or without rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arcos, A.; Morenas-Rodríguez, E.; Santamaria, J.; Sánchez-Valle, R.; Lladó, A.; Gaig, C.; Lleó, A.; Iranzo, A. Clinical and video-polysomnographic analysis of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and other sleep disturbances in dementia with Lewy bodies. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antelmi, E.; Lippolis, M.; Biscarini, F.; Tinazzi, M.; Plazzi, G. REM sleep behavior disorder: Mimics and variants. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 60, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, A.; Santamaría, J. Severe obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea mimicking REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2005, 28, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rill, E. Disorders of the reticular activating system. Med. Hypotheses 1997, 49, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, C.L.; Schenck, C.H. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in women: Relevance to general and specialty medical practice. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 1955–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revonsuo, A. The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 23, 793–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, A.; Ratti, P.L.; Casanova-Molla, J.; Serradell, M.; Vilaseca, I.; Santamaria, J. Excessive muscle activity increases over time in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 2009, 32, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, M.; Pujol, J.; Alonso, T.; Fuentes, A.; Pallerola, M.; Freixenet, J.; Barbé, F.; Salamero, M.; Santamaría, J.; Iranzo, A. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder in the elderly Spanish community: A primary care center study with a two-stage design using video-polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2017, 40, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclair-Visonneau, L.; Oudiette, D.; Gaymard, B.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Arnulf, I. Do the eyes scan dream images during rapid eye movement sleep? Evidence from the rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder model. Brain 2010, 133, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, P.; Quaranta, D.; Di Giacopo, R.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Mazza, M.; Martini, A.; Canestri, J.; Della Marca, G. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: A window on the emotional world of Parkinson disease. Sleep 2015, 38, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudiette, D.; Constantinescu, I.; Leclair-Visonneau, L.; Vidailhet, M.; Schwartz, S.; Arnulf, I. Evidence for the re-enactment of a recently learned behavior during sleepwalking. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A.; Manni, R.; Limosani, I.; Terzaghi, M.; Cavallotti, S.; Scarone, S. Challenging the myth of REM sleep behavior disorder: No evidence of heightened aggressiveness in dreams. Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallotti, S.; Stein, H.C.; Savarese, M.; Terzaghi, M.; D’Agostino, A. Aggressiveness in the dreams of drug-naïve and clonazepam-treated patients with isolated REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2022, 92, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, V.C.; Vidailhet, M.; Leu, S.; Texeira, A.; Apartis, E.; Elbaz, A.; Roze, E.; Willer, J.C.; Agid, Y.; Arnulf, I. Restoration of normal motor control in Parkinson’s disease during REM sleep. Brain 2007, 130, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, K.; Frauscher, B.; Gschliesser, V.; Wolf, E.; Falkenstetter, T.; Schoenwald, S.V.; Ehrmann, L.; Zangerl, A.; Marti, I.; Boesch, S.M.; et al. Can observers link dream content to behaviours in rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder? A cross-sectional experimental pilot study. J. Sleep Res. 2012, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, M.L.; Trenkwalder, C.; Walters, A.S.; Mollenhauer, B.; Sixel-Döring, F. REM sleep behavioral events and dreaming. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.H.; Bundlie, S.R.; Patterson, A.L.; Mahowald, M.W. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: A treatable parasomnia affecting older adults. JAMA 1987, 257, 1786–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, A.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Santamaría, J.; Serradell, M.; Martí, M.J.; Valldeoriola, F.; Tolosa, E. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder as an early marker for a neurodegenerative disorder: A descriptive study. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksenberg, A.; Radwan, H.; Arons, E.; Hoffenbach, D.; Behroozi, B. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder: A sleep disturbance affecting mainly older men. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2002, 39, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Tassinari, C.A.; Rubboli, G.; Gardella, E.; Cantalupo, G.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Vedovello, M.; Alessandria, M.; Gandini, G.; Cinotti, S.; Zamponi, N.; et al. Central pattern generators for a common semiology in fronto-limbic seizures and in parasomnias. A neuroethologic approach. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 26 (Suppl. S3), S225–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalho, P.; Paiva, T. Dream features in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnulf, I. RBD: A window into the dreaming process. In Rapid-Eye-Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, R.; Terzaghi, M.; Ratti, P.L.; Repetto, A.; Zangaglia, R.; Pacchetti, C. Hallucinations and REM sleep behaviour disorder in Parkinson’s disease: Dream imagery intrusions and other hypotheses. Conscious. Cognit. 2011, 20, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve, B.F.; Silber, M.H.; Saper, C.B.; Ferman, T.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Parisi, J.E.; Benarroch, E.E.; Ahlskog, J.E.; Smith, G.E.; Caselli, R.C.; et al. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain 2007, 130, 2770–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Gagnon, J.F.; Rompré, S.; Montplaisir, J.Y. Severity of REM atonia loss in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder predicts Parkinson disease. Neurology 2010, 74, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; An, J.; Ding, Y.; Nie, X.; Chan, P. Validation of the Beijing version of the REM sleep behavior disorder questionnaire (RBDQ-Beijing) in a mainland Chinese cohort. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2014, 234, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hefez, A.; Metz, L.; Lavie, P. Long-term effects of extreme situational stress on sleep and dreaming. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144, 344–347. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.J.; Ball, W.A.; Dinges, D.F.; Kribbs, N.B.; Morrison, A.R.; Silver, S.M.; Mulvaney, F.D. Motor dysfunction during sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep 1994, 17, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mysliwiec, V.; O’Reilly, B.; Polchinski, J.; Kwon, H.P.; Germain, A.; Roth, B.J. Trauma associated sleep disorder: A proposed parasomnia encompassing disruptive nocturnal behaviors, nightmares, and REM without atonia in trauma survivors. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, A.M.; Miller, P.P.; Carwile, S.T. REM sleep behavior disorder: Potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 18, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haba-Rubio, J.; Frauscher, B.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Toriel, J.; Tobback, N.; Andries, D.; Preisig, M.; Vollenweider, P.; Postuma, R.; Heinzer, R. Prevalence and determinants of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in the general population. Sleep 2018, 41, zsx197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros-Ferreira, M.; Chodkiewicz, J.P.; Lairy, G.C.; Salzarulo, P. Disorganized relations of tonic and phasic events of REM sleep in a case of brain-stem tumor. Electroenceph. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1975, 38, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Bundlie, S.R.; Smith, S.A.; Ettinger, M.G.; Mahowald, M.W. REM behavior disorder in a 10-year-old girl and aperiodic REM and NREM sleep movements in an 8-year-old brother. Sleep Res. 1986, 15, 162. [Google Scholar]

- Rye, D.B.; Johnston, L.H.; Watts, R.L.; Bliwise, D.L. Juvenile Parkinson’s disease with REM sleep behavior disorder, sleepiness, and daytime REM onset. Neurology 1999, 53, 1868–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Allen, W.T. REM sleep behavior disorder associated with narcolepsy in an adolescent: A case report. Sleep Res. 1990, 19, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, M.W. Motor dyscontrol in narcolepsy: Rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep without atonia and REM sleep behavior disorder. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 32, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevsimalova, S.; Prihodova, I.; Kemlink, D.; Lin, L.; Mignot, E. REM behavior disorder (RBD) can be one of the first symptoms of childhood narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 784–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumalai, S.S.; Shubin, R.A.; Robinson, R. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in children with autism. J. Child Neurol. 2002, 17, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stores, G. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder in children and adolescents. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domhoff, G.W. The invasion of the concept snatchers: The origins, distortions, and future of the continuity hypothesis. Dreaming 2017, 27, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpelli, S.; Bartolacci, C.; D’Atri, A.; Gorgoni, M.; De Gennaro, L. Mental sleep activity and disturbing dreams in the lifespan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fasiello, E.; Scarpelli, S.; Gorgoni, M.; Alfonsi, V.; De Gennaro, L. Dreaming in Parasomnias: REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Model. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216379

Fasiello E, Scarpelli S, Gorgoni M, Alfonsi V, De Gennaro L. Dreaming in Parasomnias: REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(21):6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216379

Chicago/Turabian StyleFasiello, Elisabetta, Serena Scarpelli, Maurizio Gorgoni, Valentina Alfonsi, and Luigi De Gennaro. 2022. "Dreaming in Parasomnias: REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Model" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 21: 6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216379

APA StyleFasiello, E., Scarpelli, S., Gorgoni, M., Alfonsi, V., & De Gennaro, L. (2022). Dreaming in Parasomnias: REM Sleep Behavior Disorder as a Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6379. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216379