Suspicious Positive Peritoneal Cytology (Class III) in Endometrial Cancer Does Not Affect Prognosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility of Patients

2.2. Clinical Information

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, A.S.; Key, T.J.; Norat, T.; Scoccianti, C.; Cecchini, M.; Berrino, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Espina, C.; Leitzmann, M.; Powers, H.; et al. European code against cancer. 4th ed: Obesity, body fatness and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, S34–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, J.A.; Darus, C.J.; Rice, L.W. Surgical management and postoperative treatment of endometrial carcinoma. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorelli, S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 105, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasamatsu, T.; Onda, T.; Katsumata, N.; Sawada, M.; Yamada, T.; Tsunematsu, R.; Ohmi, K.; Sasajima, Y.; Matsuno, Y. Prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma confined to the uterus. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, G.; Gao, F.; Wright, J.D.; Hagemann, A.R.; Mutch, D.G.; Powell, M.A. Positive peritoneal cytology is an independent risk-factor in early stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 128, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, K.; Matsuzaki, S.; Nusbaum, D.J.; Roman, L.D.; Wright, J.D.; Harter, P.; Klar, M. Association between adjuvant therapy and survival in Stage II–III endometrial cancer: Influence of malignant peritoneal cytology. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 7591–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Chandra, A.; Crothers, B.A.; Kurtycz, D.F.I.; Schmitt, F. The international system for reporting serous fluid cytopathology-diagnostic categories and clinical management. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2020, 9, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashimura, M.; Sugihara, K.; Toki, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Kawagoe, T.; Kamura, T.; Kaku, T.; Tsuruchi, N.; Nakashima, H.; Sakai, H. The significance of peritoneal cytology in uterine cervix and endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 1997, 67, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomovitz, B.M. Heterogeneity of stage IIIA endometrial carcinomas: Implications for adjuvant therapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2005, 15, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Shi, W.; Barakat, R.R.; Thaler, H.T.; Saigo, P.E. Peritoneal washings in endometrial carcinoma. A study of 298 patients with histopathologic correlation. Acta Cytol. 2000, 44, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saga, Y.; Imai, M.; Jobo, T.; Kuramoto, H.; Takahashi, K.; Konno, R.; Ohwada, M.; Suzuki, M. Is peritoneal cytology a prognostic factor of endometrial cancer confined to the uterus? Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 103, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, K.; Wright, J.D.; Matsuzaki, S.; Roman, L.D.; Harter, P.; Klar, M. Malignant peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer: Areas of unmet need for evidence. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 140, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoniem, K.; Larish, A.M.; Dinoi, G.; Zhou, X.C.; Alhilli, M.; Wallace, S.; Wohlmuth, C.; Baiocchi, G.; Tokgozoglu, N.; Raspagliesi, F. Oncologic outcomes of endometrial cancer in patients with low-volume metastasis in the sentinel lymph nodes: An international multi-institutional study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogani, G.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Concin, N.; Ngoi, N.Y.L.; Morice, P.; Enomoto, T.i.; Takehara, K.; Denys, H.; Nout, R.A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. Uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, H.; Saga, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Ohwada, M.; Enomoto, A.; Konno, R.; Tanaka, A.; Suzuki, M. Omental metastases in clinical stage I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2008, 18, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metindir, J.; Dilek, G.B. The role of omentectomy during the surgical staging in patients with clinical stage I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 134, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Taguchi, A.; Fukui, Y.; Kawata, A.; Taguchi, S.; Kashiyama, T.; Eguchi, S.; Inoue, T.; Tomio, K.; Tanikawa, M.; et al. Blood vessel invasion is a strong predictor of postoperative recurrence in endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Patients (n = 670) | |

|---|---|

| Age [year], median (range) | 55 (23–93) |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | |

| I | 483 (72%) |

| II | 53 (7.9%) |

| III | 117 (17.5%) |

| IV | 17 (2.5%) |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%) | |

| <1/2 | 451 (67.3%) |

| ≥1/2 | 219 (32.7%) |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | |

| Negative | 578 (86.3%) |

| Positive | 92 (13.7%) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| EMG1 | 442 (66%) |

| EMG2 | 99 (14.8%) |

| EMG3 | 54 (8.0%) |

| Others | 75 (11.1%) |

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | 18 (2.7%) |

| Adnexal metastasis, n (%) | 24 (3.6%) |

| Peritoneal cytology, n (%) | |

| Negative | 553 (82.5%) |

| Suspicious | 39 (5.8%) |

| Positive | 78 (11.6%) |

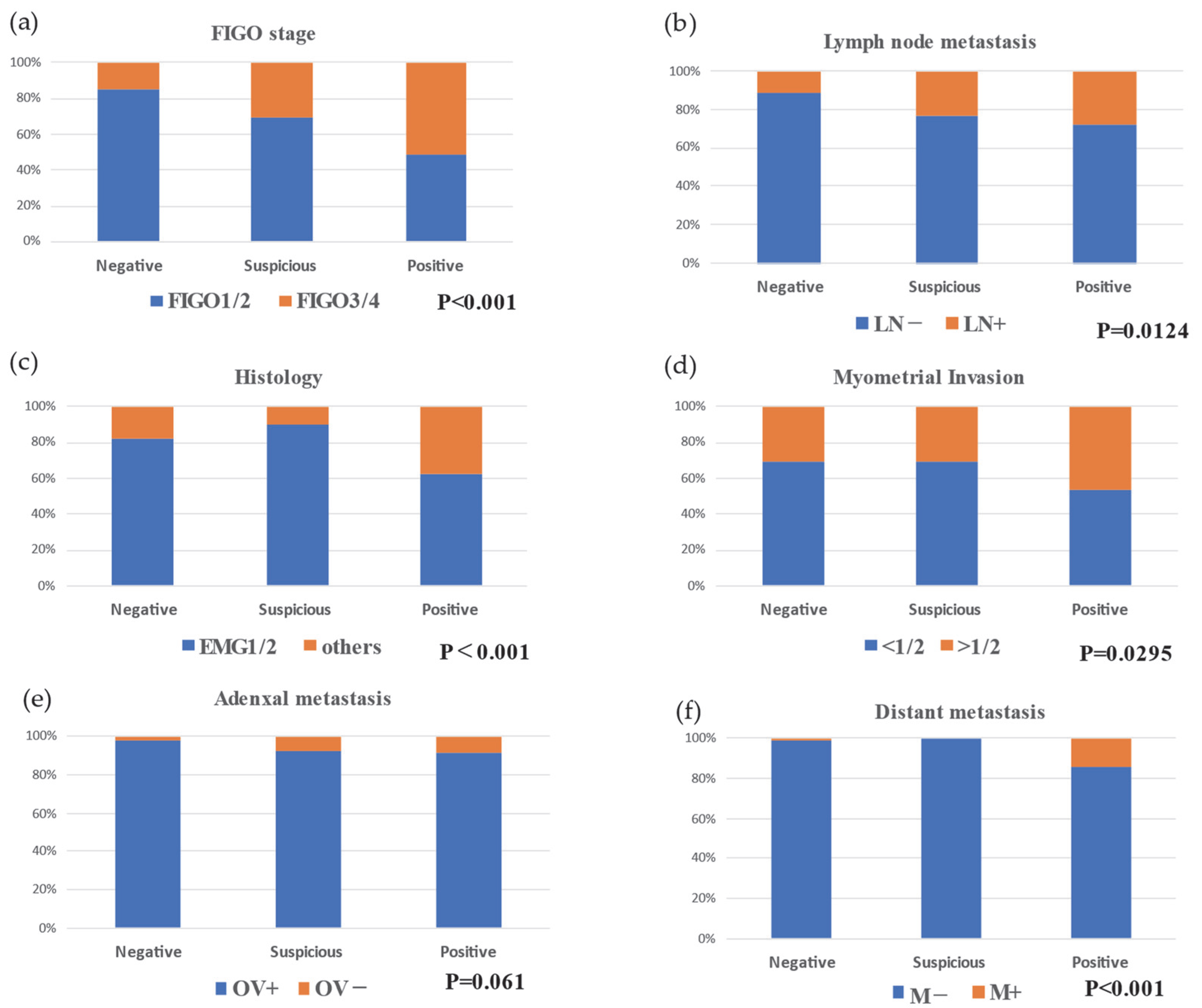

| Negative (n = 553) | Suspicious (n = 39) | Positive (n = 78) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 56 (23–93) | 53 (33–78) | 54.5 (26–79) |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | |||

| I | 424 (76.7) | 25 (64.1) | 34 (43.6) |

| II | 47 (8.5) | 2 (5.1) | 4 (5.1) |

| III | 75 (13.6) | 12 (30.8) | 30 (38.5) |

| IV | 7 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.8) |

| Myometrial invasion, n (%) | |||

| <1/2 | 382 (69.1) | 27 (69.2) | 42 (53.8) |

| ≥1/2 | 171 (30.9) | 12 (30.8) | 36 (46.2) |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 61 (11.0) | 9 (23.1) | 22 (28.2) |

| Positive | 492 (89.0) | 30 (76.9) | 56 (71.8) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| EMG1 | 384 (69.4) | 26 (66.7) | 32 (41.0) |

| EMG2 | 73 (13.2) | 9 (23.1) | 17 (21.8) |

| EMG3 | 42 (7.6) | 4 (10.3) | 8 (10.3) |

| Others | 54 (9.8) | 0 (0) | 21 (26.9) |

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 7 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (14.1) |

| Positive | 546 (98.7) | 39 (100) | 67 (85.9) |

| Ovarian metastasis, n (%) | |||

| Negative | 14 (2.5) | 3 (7.7) | 7 (9.0) |

| Positive | 539 (97.5) | 36 (92.3) | 71 (91.0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sone, K.; Suzuki, E.; Taguchi, A.; Honjoh, H.; Nishijima, A.; Eguchi, S.; Miyamoto, Y.; Iriyama, T.; Mori, M.; Osuga, Y. Suspicious Positive Peritoneal Cytology (Class III) in Endometrial Cancer Does Not Affect Prognosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216527

Sone K, Suzuki E, Taguchi A, Honjoh H, Nishijima A, Eguchi S, Miyamoto Y, Iriyama T, Mori M, Osuga Y. Suspicious Positive Peritoneal Cytology (Class III) in Endometrial Cancer Does Not Affect Prognosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(21):6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216527

Chicago/Turabian StyleSone, Kenbun, Eri Suzuki, Ayumi Taguchi, Harunori Honjoh, Akira Nishijima, Satoko Eguchi, Yuichiro Miyamoto, Takayuki Iriyama, Mayuyo Mori, and Yutaka Osuga. 2022. "Suspicious Positive Peritoneal Cytology (Class III) in Endometrial Cancer Does Not Affect Prognosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 21: 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216527

APA StyleSone, K., Suzuki, E., Taguchi, A., Honjoh, H., Nishijima, A., Eguchi, S., Miyamoto, Y., Iriyama, T., Mori, M., & Osuga, Y. (2022). Suspicious Positive Peritoneal Cytology (Class III) in Endometrial Cancer Does Not Affect Prognosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11216527