Treatments for Staple Line Leakage after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Features of Sleeve Leakage

3.1. Causes of Sleeve Leakage

3.2. Symptoms and Timing of Onset of Sleeve Leakage

4. Diagnosis of Sleeve Leakage

5. Treatments of Sleeve Leakage

Initial Treatments for Sleeve Leakage

6. Conservative Treatment following Initial Treatments

6.1. Kangaroo™ W-ED Tube (Figure 1)

6.2. Over-The-Scope-Clip (OTSC®) (Figure 2)

6.3. Endoscopic Balloon Dilation

6.4. Stent Placement

6.5. Percutaneous Transesophageal Gastro-Tubing (PTEG)

6.6. Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy (EVAC)

7. Reoperation (Revisional Surgery)

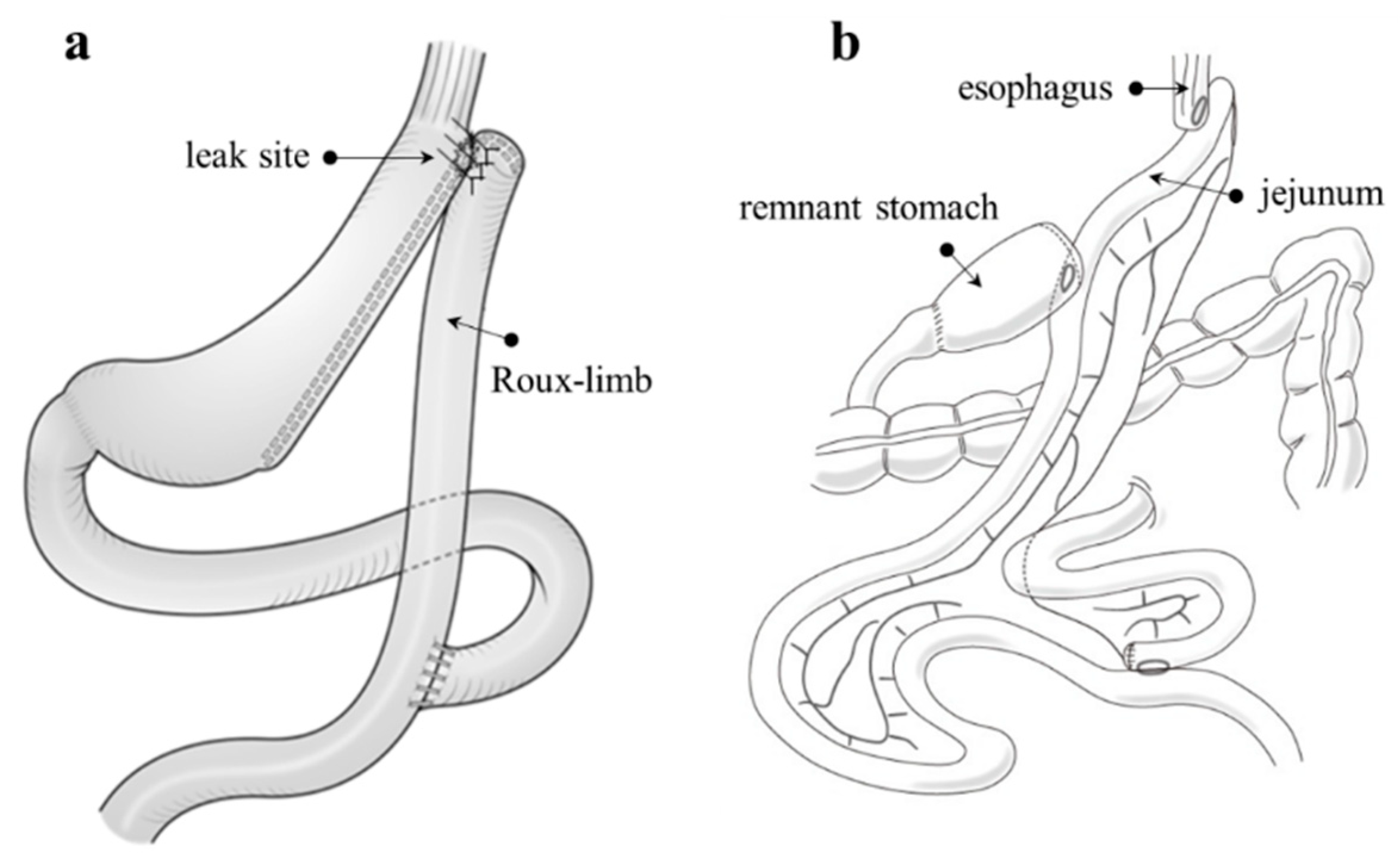

7.1. Fistulo-Jejunostomy (Figure 7a)

7.2. Total or Proximal Gastrectomy

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Seventh IFSO Global Registry Report. Available online: https://www.ifso.com/pdf/ifso-7th-registry-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Sasaki, A.; Yokote, K.; Naitoh, T.; Fujikura, J.; Hayashi, K.; Hirota, Y.; Inagaki, N.; Ishigaki, Y.; Kasama, K.; Kikkawa, E.; et al. Metabolic surgery in treatment of obese Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: A joint consensus statement from the Japanese Society for Treatment of Obesity, the Japan Diabetes Society, and the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimeri, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Maasher, A.; Al Hadad, M. Management algorithm for leaks following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, M.; Kasama, K.; Sasaki, A.; Naitoh, T.; Seki, Y.; Inamine, S.; Oshiro, T.; Doki, Y.; Seto, Y.; Hayashi, H.; et al. Current status of laparoscopic bariatric/metabolic surgery in Japan: The sixth nationwide survey by the Japan Consortium of Obesity and Metabolic Surgery. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2021, 14, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.; Kasama, K.; Nabekura, T.; Sato, Y.; Kitahara, T.; Matsunaga, R.; Arai, M.; Kadoya, K.; Nagashima, M.; Okazumi, S. Current status and issues associated with bariatric and metabolic surgeries in Japan. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshiro, T.; Sato, Y.; Nabekura, T.; Kitahara, T.; Sato, A.; Kadoya, K.; Kawamitsu, K.; Takagi, R.; Nagashima, M.; Okazumi, S.; et al. Proximal gastrectomy with double tract reconstruction is an alternative revision surgery for intractable complications after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 3333–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Azagury, D.; Eisenberg, D.; DeMaria, E.; Campos, G.M.; American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. ASMBS position statement on prevention, detection, and treatment of gastrointestinal leak after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, including the roles of imaging, surgical exploration, and nonoperative management. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Bhojwani, R.; Mahawar, K. Leaks after sleeve gastrectomy—A narrative review. J. Bariatr. Surg. 2022, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Rached, A.; Basile, M.; El Masri, H. Gastric leaks post sleeve gastrectomy: Review of its prevention and management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 13904–13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.J.; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel; Diaz, A.A.; Arvidsson, D.; Baker, R.S.; Basso, N.; Bellanger, D.; Boza, C.; El Mourad, H.; France, M.; et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: Best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2012, 8, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csendes, A.; Braghetto, I.; León, P.; Burgos, A.M. Management of leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with obesity. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010, 14, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zoubi, M.; Khidir, N.; Bashah, M. Challenges in the diagnosis of leak after sleeve gastrectomy: Clinical presentation, laboratory, and radiological findings. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Issues Committee of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery position statement on emergency care of patients with complications related to bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2010, 6, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashah, M.; Khidir, N.; El-Matbouly, M. Management of leak after sleeve gastrectomy: Outcomes of 73 cases, treatment algorithm and predictors of resolution. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.L.; Zhu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Peng, J.Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Xie, Z.C. Effect of omentopexy/gastropexy on gastrointestinal symptoms after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and systematic review. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamori, Y.; Sakurai, K.; Kubo, N.; Yonemitsu, K.; Fukui, Y.; Nishimura, J.; Maeda, K.; Nishiguchi, Y. Percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing for the management of anastomotic leakage after upper GI surgery: A report of two clinical cases. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobara, H.; Mori, H.; Nishiyama, N.; Fujihara, S.; Okano, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Masaki, T. Over-the-scope clip system: A review of 1517 cases over 9 years. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslauriers, V.; Beauchamp, A.; Garofalo, F.; Atlas, H.; Denis, R.; Garneau, P.; Pescarus, R. Endoscopic management of post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy stenosis. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.; Kasama, K.; Umezawa, A.; Kanehira, E.; Kurokawa, Y. Successful management of refractory staple line leakage at the esophagogastric junction after a sleeve gastrectomy using the HANAROSTENT. Obes. Surg. 2010, 20, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billmann, F.; Pfeiffer, A.; Sauer, P.; Billeter, A.; Rupp, C.; Koschny, R.; Nickel, F.; von Frankenberg, M.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Schaible, A. Endoscopic stent placement can successfully treat gastric leak following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy if and only if an esophagoduodenal megastent is used. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.; Saiki, A.; Suzuki, J.; Satoh, A.; Kitahara, T.; Kadoya, K.; Moriyama, A.; Ooshiro, M.; Nagashima, M.; Park, Y.; et al. Percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing for management of gastric leakage after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.; Nabekura, T.; Kitahara, T.; Takenouchi, A.; Moriyama, Y.; Kitahara, N.; Nagashima, M.; Okazumi, S. Techniques for percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing in the management of gastric leak or dysphasia after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 1399–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, H.; Shindo, H.; Shirotani, N.; Kameoka, S. A nonsurgical technique to create an esophagostomy for difficult cases of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 1224–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, C.; Berlth, F.; Tagkalos, E.; Hadzijusufovic, E.; Lang, H.; Grimminger, P. Endoscopic management of complications—Endovacuum for management of anastomotic leakages: A narrative review. Ann. Esophagus 2022, 5, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.M.; Pereira, E.F.; Evangelista, L.F.; Siqueira, L.; Neto, M.G.; Dib, V.; Falcão, M.; Arantes, V.; Awruch, D.; Albuquerque, W.; et al. Gastrobronchial fistula after sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: Endoscopic management and prevention. Obes. Surg. 2011, 21, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannelli, A.; Tavana, R.; Martini, F.; Noel, P.; Gugenheim, J. Laparoscopic roux limb placement over a fistula defect without mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis: A modified technique for surgical management of chronic proximal fistulas after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedix, F.; Poranzke, O.; Adolf, D.; Wolff, S.; Lippert, H.; Arend, J.; Manger, T.; Stroh, C.; Obesity Surgery Working Group Competence Network Obesity. Staple line leak after primary sleeve gastrectomy-risk factors and midterm results: Do patients still benefit from the weight loss procedure? Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, Á.A.B.; Feitosa, P.H.F.; Santa-Cruz, F.; Aquino, M.R.; Dompieri, L.T.; Santos, E.M.; Siqueira, L.T.; Kreimer, F. Gastric fistula after sleeve gastrectomy: Clinical features and treatment options. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Suggested Good Indications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| W-ED tube® |

|

|

|

| OTSC® |

|

|

|

| Endoscopic balloon dilation |

|

|

|

| Stent |

|

|

|

| PTEG |

|

|

|

| EVAC |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oshiro, T.; Wakamatsu, K.; Nabekura, T.; Moriyama, Y.; Kitahara, N.; Kadoya, K.; Sato, A.; Kitahara, T.; Urita, T.; Sato, Y.; et al. Treatments for Staple Line Leakage after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103495

Oshiro T, Wakamatsu K, Nabekura T, Moriyama Y, Kitahara N, Kadoya K, Sato A, Kitahara T, Urita T, Sato Y, et al. Treatments for Staple Line Leakage after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(10):3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103495

Chicago/Turabian StyleOshiro, Takashi, Kotaro Wakamatsu, Taiki Nabekura, Yuki Moriyama, Natsumi Kitahara, Kengo Kadoya, Ayami Sato, Tomoaki Kitahara, Tasuku Urita, Yu Sato, and et al. 2023. "Treatments for Staple Line Leakage after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 10: 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103495