Tolerability and Safety of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Tree Pollen Allergy in Daily Practice—An Open, Prospective, Non-Interventional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Study Treatment

2.5. Safety and Tolerability Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Epidemiological Data

3.2. Number of Patients Who Reached the Maintenance Dose of Five Drops

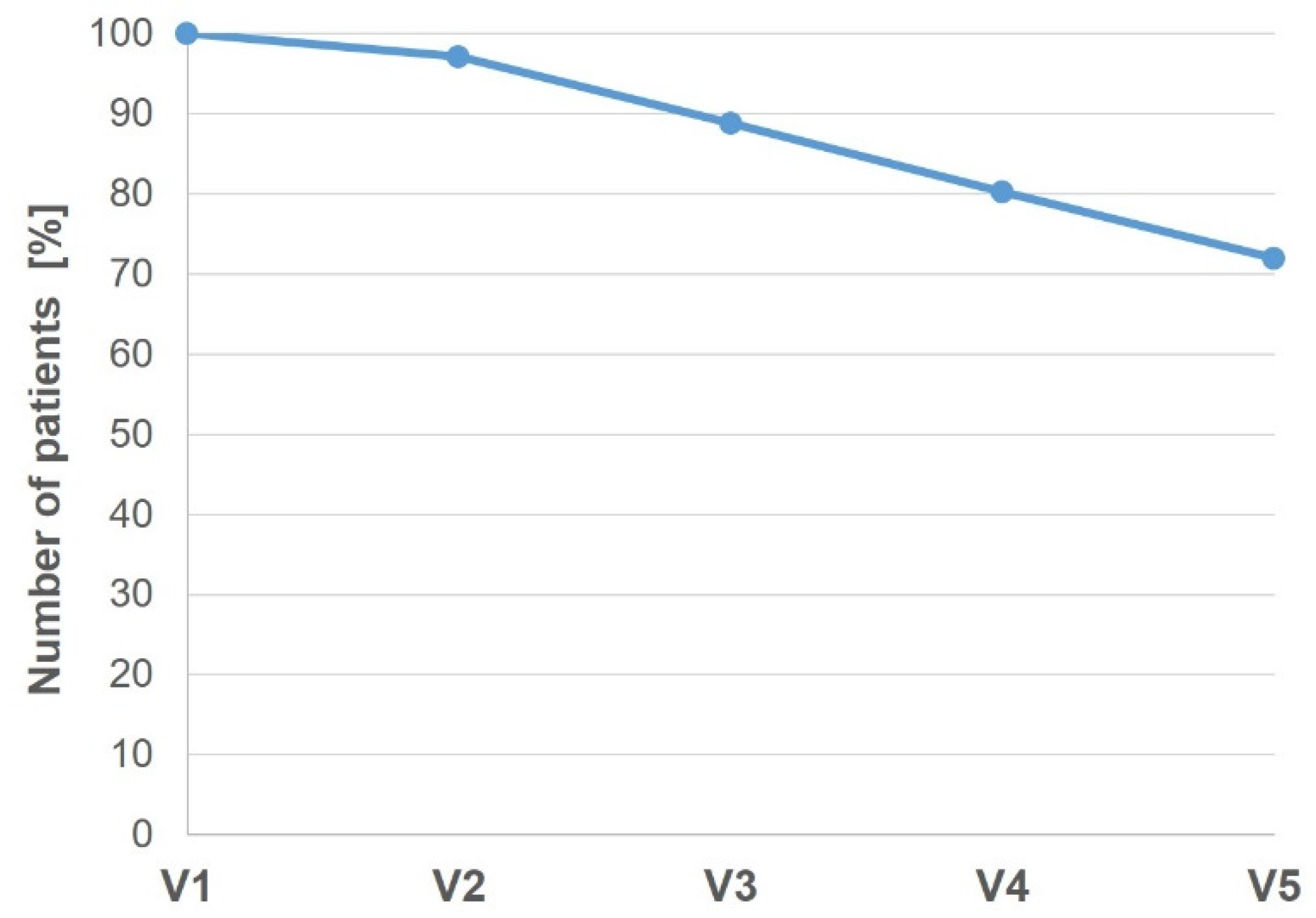

3.3. Study Adherence and Treatment Compliance

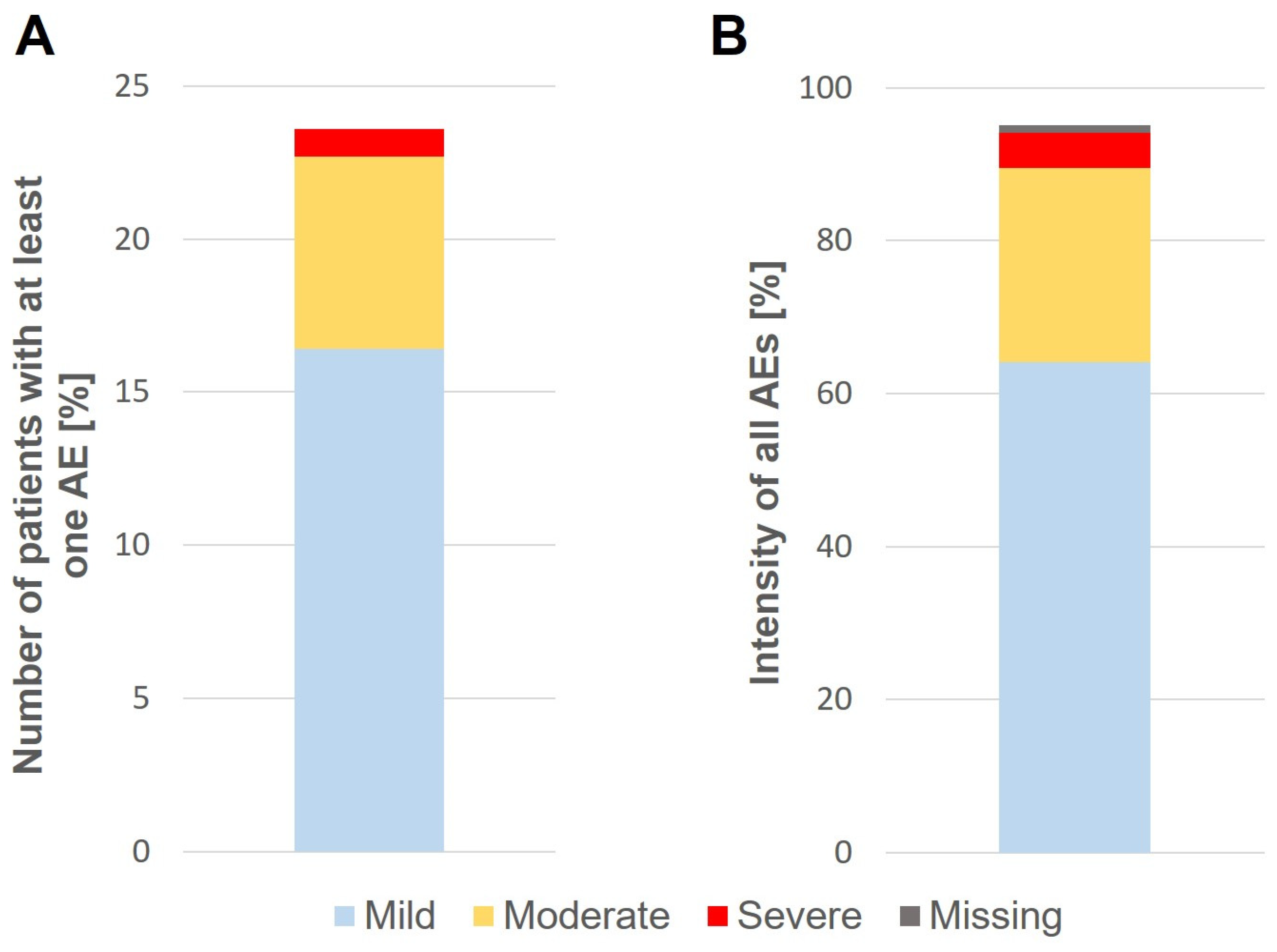

3.4. Safety and Tolerability

3.5. Treatment Satisfaction

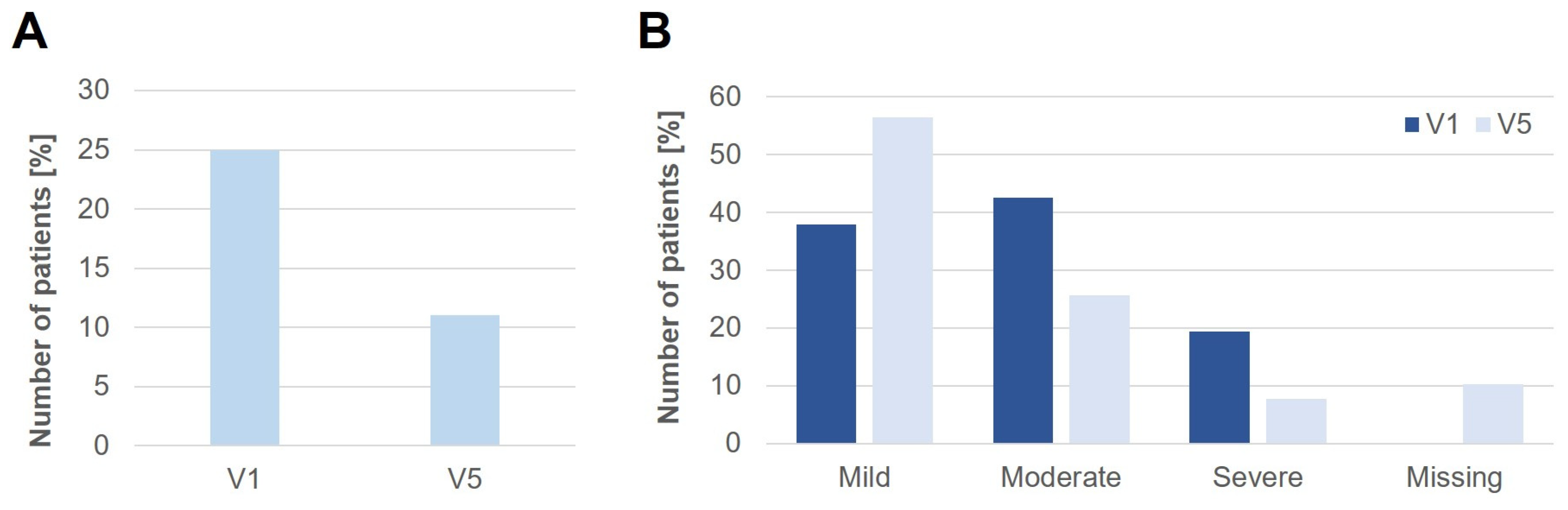

3.6. Change of Oral Allergy Syndrome (OAS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, G.; Pfaar, O.; Akdis, C.A.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Durham, S.R.; Gerth van Wijk, R.; Halken, S.; Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Pawankar, R.; Pitsios, C. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy 2018, 73, 765–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Khaltaev, N.; Cruz, A.A.; Denburg, J.; Fokkens, W.J.; Togias, A.; Zuberbier, T.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Canonica, G.W.; van Weel, C. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008. Allergy 2008, 63, 8–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, T.; Winther, L.; Till, S.J.; Panzner, P.; Knulst, A.; Valovirta, E. Birch pollen allergy in Europe. Allergy 2019, 74, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt Verordnung über die Ausdehnung der Vorschriften über die Zulassung der Arzneimittel auf Therapieallergene, die für einzelne Personen auf Grund einer Rezeptur hergestellt werden, sowie über Verfahrensregelung der staatlichen Chargenprüfung (Therapieallergene-Verordnung). Bundesgesetzesblatt 2008; Teil I Nr., 51. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tav/BJNR217700008.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Pfaar, O.; van Twuijver, E.; Boot, J.D.; Opstelten, D.J.E.; Klimek, L.; van Ree, R.; Diamant, Z.; Kuna, P.; Panzner, P. A randomized DBPC trial to determine the optimal effective and safe dose of a SLIT-birch pollen extract for the treatment of allergic rhinitis: Results of a phase II study. Allergy 2016, 71, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaar, O.; Demoly, P.; Gerth van Wijk, R.; Bonini, S.; Bousquet, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Durham, S.R.; Jacobsen, L.; Malling, H.J.; Mösges, R. Recommendations for the standardization of clinical outcomes used in allergen immunotherapy trials for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: An EAACI Position Paper. Allergy 2014, 69, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaar, O.; Bachert, C.; Kuna, P.; Panzner, P.; Džupinová, M.; Klimek, L.; van Nimwegen, M.J.; Boot, J.D.; Yu, D.; Opstelten, D.J.E. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy with a liquid birch pollen product in patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis with or without asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summary of Product Characteristics SUBLIVAC® Birke and SUBLIVAC® Bäume. Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/amispb/doc/pei/Web/2613842-spcde-20180601.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Passalacqua, G.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Bousquet, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Casale, T.B.; Cox, L.; Durham, S.R.; Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Ledford, D.; Pawankar, R. Grading local side effects of sublingual immunotherapy for respiratory allergy: Speaking the same language. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, L.; Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Lockey, R.F.; Passalacqua, G. Speaking the same language: The World Allergy Organization subcutaneous immunotherapy systemic reaction grading system. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisacher, W.R.; Visaya, J.M. Patient adherence to allergy immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 21, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, F.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Arifhodzic, N.; Al-Herz, W. Compliance with allergen immunotherapy and factors affecting compliance among patients with respiratory allergies. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Sklar, G.E.; Oh, V.M.; sen Li, S.C. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pfaar, O.; Bachert, C.; Bufe, A.; Buhl, R.; Ebner, C.; Eng, P.; Friedrichs, F.; Fuchs, T.; Hamelmann, E.; Hartwig-Bade, D. Guideline on allergen-specific immunotherapy in IgE-mediated allergic diseases. Allergo J. Int. 2014, 23, 282–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, J.; Beyer, K.; Biedermann, T.; Bircher, A.; Fischer, M.; Fuchs, T.; Heller, A.; Hoffmann, F.; Huttegger, I.; Jakob, T. Guideline (S2k) on acute therapy and management of anaphylaxis: 2021 update. Allergo J. Int. 2021, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemberg, M.-L.; Berk, T.; Shah-Hosseini, K.; Kasche, E.-M.; Mösges, R. Sublingual versus subcutaneous immunotherapy: Patient adherence at a large German allergy center. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makatsori, M.; Scadding, G.W.; Lombardo, C.; Bisoffi, G.; Ridolo, E.; Durham, S.R.; Senna, G. Dropouts in sublingual allergen immunotherapy trials–a systematic review. Allergy 2014, 69, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, M.A.; Röder, E.; van Wijk, R.G.; Al, M.J.; Hop, W.C.J.; Rutten-van Mölken, M.P.M.H. Real-life compliance and persistence among users of subcutaneous and sublingual allergen immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incorvaia, C.; Mauro, M.; Ridolo, E.; Puccinelli, P.; Liuzzo, M.; Scurati, S.; Frati, F. Patient’s compliance with allergen immunotherapy. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2008, 2, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelberg, C.; Brüggenjürgen, B.; Richter, H.; Jutel, M. Real-world adherence and evidence of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy in grass and tree pollen-induced allergic rhinitis and asthma. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, G.W.; Cox, L.; Pawankar, R.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Blaiss, M.; Bonini, S.; Bousquet, J.; Calderón, M.; Compalati, E.; Durham, S.R. Sublingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization position paper 2013 update. World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaar, O.; Ankermann, T.; Augustin, M.; Bubel, P.; Böing, S.; Brehler, R.; Eng, P.A.; Fischer, P.J.; Gerstlauer, M.; Hamelmann, E.; et al. Leitlinie zur Allergen-Immuntherapie bei IgE-vermittelten allergischen Erkrankungen. Allergologie 2022, 45, 643–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsios, C.; Dietis, N. Ways to increase adherence to allergen immunotherapy. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019, 35, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, K.-C.; Wolf, H.; Schnitker, J. Effect of pollen-specific sublingual immunotherapy on oral allergy syndrome: An observational study. World Allergy Organ. J. 2008, 1, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, S.J.; Stage, B.S.; Skypala, I.; Biedermann, T. Potential treatment effect of the SQ tree SLIT-tablet on pollen food syndrome caused by apple. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 75, ALL14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, G.; Sussman, A.; Sussman, D. Oral allergy syndrome. CMAJ 2010, 182, 1210–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Alessandri, C.; Ferrara, R.; Bernardi, M.L.; Zennaro, D.; Tuppo, L.; Giangrieco, I.; Ricciardi, T.; Tamburrini, M.; Ciardiello, M.A.; Mari, A. Molecular approach to a patient’s tailored diagnosis of the oral allergy syndrome. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muluk, N.B.; Cingi, C. Oral allergy syndrome. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2018, 32, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Visits | Purpose | Description |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | Screening | Review of inclusion and exclusion criteria and collection of demographic data, medical history, concomitant diseases, and medication use |

| V2 | Administration | Initial administration of sublingual treatment |

| V3 | Maintenance | Documentation of treatment adherence and the occurrence AEs |

| V4 | ||

| V5 | Final visit | Recording of AEs and patient satisfaction |

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 189 (43.8) |

| Female | 243 (56.3) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) [years] | 44.3 (14.6) |

| Median (Min–Max) | 44.0 (19.0–83.0) |

| Asthma | |

| Yes | 51 (11.8) |

| No | 381 (88.2) |

| Oral allergy syndrome | |

| Yes | 108 (25.0) |

| No | 324 (75.0) |

| Treatment | |

| SBPE | 208 (48.1) |

| STPE | 224 (51.9) |

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance dose | 385 (96.0) | 16 (4.0) | 401 (100.0) |

| Maintenance dose within 5 days | 363 (94.3) | 22 (5.7) | 385 (100.0) |

| Parameters | SBPE (n = 208) n (%) | STPE (n = 224) n (%) | Total (n = 432) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least one LR | Σ | 47 (22.6) | 49 (21.9) | 96 (22.2) |

| Strongest intensity | Mild | 39 (18.8) | 30 (13.4) | 69 (16.0) |

| Moderate | 7 (3.4) | 17 (7.6) | 24 (5.6) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Number of all LR | Σ | 124 (100) | 147 (100) | 271 (100) |

| Intensity | Missing | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) |

| Mild | 104 (83.9) | 98 (66.7) | 202 (74.5) | |

| Moderate | 14 (11.3) | 41 (27.9) | 55 (20.3) | |

| Severe | 3 (2.4) | 8 (5.4) | 11 (4.1) | |

| Patients with at least one SR | Σ | 9 (4.3) | 18 (8.0) | 27 (6.3) |

| Strongest intensity | Missing | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (1.6) |

| Grade 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Grade I | 2 (1.0) | 9 (4.0) | 11 (2.5) | |

| Grade II | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.2) | 6 (1.4) | |

| Grade III | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Number of all SR | Σ | 20 (100.0) | 37 (100.0) | 57 (100.0) |

| Intensity | Missing | 7 (35.0) | 7 (18.9) | 14 (24.6) |

| Grade 0 | 4 (20.0) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Grade I | 4 (20.0) | 20 (54.1) | 24 (42.1) | |

| Grade II | 2 (10.0) | 9 (24.3) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Grade III | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.3) | |

| Patients with at least one OR | Σ | 2 (1.0) | 11 (4.9) | 13 (3.0) |

| Strongest intensity | Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) |

| Mild | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (0.9) | |

| Moderate | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (1.2) | |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Number of all OR | Σ | 2 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) |

| Intensity | Missing | 0 (0.0) | 10 (47.6) | 10 (43.5) |

| Mild | 1 (50.0) | 4 (19.0) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Moderate | 1 (50.0) | 6 (28.6) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Treatment Satisfaction | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Very satisfied | 208 (58.9) |

| Satisfied | 140 (39.7) |

| Unsatisfied | 4 (1.1) |

| Very unsatisfied | 1 (0.3) |

| Total | 353 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owenier, C.; Barnowski, C.; Leineweber, M.; Yu, D.; Verhagen, M.; Distler, A. Tolerability and Safety of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Tree Pollen Allergy in Daily Practice—An Open, Prospective, Non-Interventional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175517

Owenier C, Barnowski C, Leineweber M, Yu D, Verhagen M, Distler A. Tolerability and Safety of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Tree Pollen Allergy in Daily Practice—An Open, Prospective, Non-Interventional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(17):5517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175517

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwenier, Christoph, Cornelia Barnowski, Margret Leineweber, Donghui Yu, Marjan Verhagen, and Andreas Distler. 2023. "Tolerability and Safety of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Tree Pollen Allergy in Daily Practice—An Open, Prospective, Non-Interventional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 17: 5517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175517

APA StyleOwenier, C., Barnowski, C., Leineweber, M., Yu, D., Verhagen, M., & Distler, A. (2023). Tolerability and Safety of Sublingual Immunotherapy in Patients with Tree Pollen Allergy in Daily Practice—An Open, Prospective, Non-Interventional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(17), 5517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175517