Current Approach in the Management of Secondary Immunodeficiency in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Spanish Expert Consensus Recommendations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

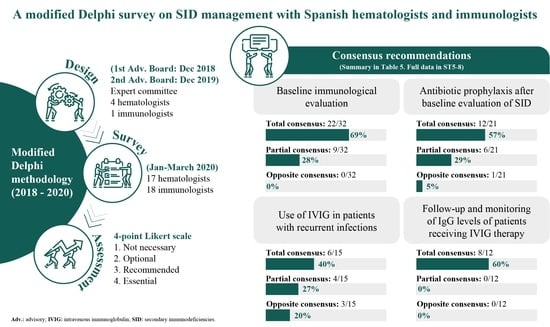

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Survey Questionnaire and Participants

2.3. Assessment

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Current Clinical Practice

3.2.1. Baseline Immunological Assessment

3.2.2. Prophylaxis of Infection

3.2.3. Treatment with IVIG and Follow-Up

3.3. Recommendations

3.3.1. Baseline Immunological Evaluation

3.3.2. Prophylaxis of Infection

3.3.3. Use of IVIG and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Srivastava, S.; Wood, P. Secondary antibody deficiency—Causes and approach to diagnosis. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Chapel, H.; Cunningham-Rundles, C. On the relevance of immunodeficiency evaluation in haematological cancer. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 39, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, P.; Morrison, V. Infectious Complications of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Semin. Oncol. 2006, 33, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhalla, F.; Lucas, M.; Schuh, A.; Bhole, M.; Jain, R.; Patel, S.Y.; Misbah, S.; Chapel, H. Antibody Deficiency Secondary to Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Should Patients be Treated with Prophylactic Replacement Immunoglobulin? J. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 34, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, H.M.; Birtwistle, J.; Whitelegg, A.; Hudson, C.; McSkeane, T.; Hazlewood, P.; Mudongo, N.; Pratt, G.; Moss, P.; Drayson, M.T.; et al. Poor functional antibody responses are present in nearly all patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, irrespective of total IgG concentration, and are associated with increased risk of infection. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 171, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Rajkumar, S.V. Drug Therapy: Multiple Myeloma. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chen, W.; Gao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Song, X.; Zheng, S.; Liu, J. Secondary Immunodeficiency and Hypogammaglobulinemia with IgG Levels of <5 g/L in Patients with Multiple Myeloma: A Retrospective Study Between 2012 and 2020 at a University Hospital in China. Experiment 2021, 27, e930241-1–e930241-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, R.L. Personalized Therapy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2019, 39, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedian, M.; Randhawa, I. Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy: A Twenty-Year Review and Current Update. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 164, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, A.; Crescenzi, L.; Granata, F.; Genovese, A.; Spadaro, G. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy in primary and secondary antibody deficiency: The correct clinical approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 52, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Chapel, H.; Litzman, J. When to initiate immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IGRT) in antibody deficiency: A practical approach. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 188, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.E.; Orange, J.S.; Bonilla, F.; Chinen, J.; Chinn, I.K.; Dorsey, M.; El-Gamal, Y.; Harville, T.O.; Hossny, E.; Mazer, B.; et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: A review of evidence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolles, S.; Michallet, M.; Agostini, C.; Albert, M.H.; Edgar, D.; Ria, R.; Trentin, L.; Lévy, V. Treating secondary antibody deficiency in patients with haematological malignancy: European expert consensus. Eur. J. Haematol. 2021, 106, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Core SmPC for Human Normal Immunoglobulin Administration. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-core-smpc-human-normal-immunoglobulin-intravenous-administration-ivig-rev-6_en.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Bermúdez, A.; González-Granado, L.I.; Rodríguez-Gallego, C.; Sastre, A.; Soler-Palacín, P. The ID-Signal Onco-Haematology Group Primary and Secondary Immunodeficiency Diseases in Oncohaematology: Warning Signs, Diagnosis, and Management. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnas, J.L.; Looney, R.J.; Anolik, J.H. B cell targeted therapies in autoimmune disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019, 61, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnall, J.R.; Maples, K.T.; Harvey, R.D.; Moore, D.C. Daratumumab for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma: A Review of Clinical Applicability and Operational Considerations. Ann. Pharmacother. 2022, 56, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.S. Anti-CD19 CAR T-Cell Therapy for B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2020, 34, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haideri, M.; Tondok, S.B.; Safa, S.H.; Maleki, A.H.; Rostami, S.; Jalil, A.T.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Alsaikhan, F.; Rizaev, J.A.; Mohammad, T.A.M.; et al. CAR-T cell combination therapy: The next revolution in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; de Seze, J.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.-P.; Hemmer, B.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Placebo in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viardot, A.; Goebeler, M.-E.; Hess, G.; Neumann, S.; Pfreundschuh, M.; Adrian, N.; Zettl, F.; Libicher, M.; Sayehli, C.; Stieglmaier, J.; et al. Phase 2 study of the bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody blinatumomab in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2016, 127, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaki, R.; Vogler, M.; Walter, H.S.; Jayne, S.; Dinsdale, D.; Siebert, R.; Dyer, M.J.S.; Yoshizawa, T. Responses to the selective Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitor tirabrutinib (ONO/GS-4059) in Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell lines. Cancers 2018, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, B.; Robak, T.; Montserrat, E.; Ghia, P.; Niemann, C.; Kater, A.; Gregor, M.; Cymbalista, F.; Buske, C.; Hillmen, P.; et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 32, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Varpio, L.; Wood, T.J.; Gonsalves, C.; Ufholz, L.-A.; Mascioli, K.; Wang, C.; Foth, T. The Use of the Delphi and Other Consensus Group Methods in Medical Education Research: A Review. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Tonacci, A.; Musolino, C.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Secondary Immunodeficiency in Hematological Malignancies: Focus on Multiple Myeloma and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 738915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdar, A.; Armstrong, D. Infections in Patients With Hematologic Neoplasms and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Neutropenia, Humoral, and Splenic Defects. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, V.; Winqvist, O.; Blimark, C.; Langerbeins, P.; Chapel, H.; Dhalla, F. Secondary immunodeficiency in lymphoproliferative malignancies. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnz-Różyk, K.; Więsik-Szewczyk, E.; Roliński, J.; Siedlar, M.; Jędrzejczak, W.; Sydor, W.; Tomaszewska, A. Secondary immunodeficiencies with predominant antibody deficiency: Multidisciplinary perspectives of Polish experts. Central Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 45, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbrahim, O.; Viallard, J.-F.; Choquet, S.; Royer, B.; Bauduer, F.; Decaux, O.; Crave, J.-C.; Fardini, Y.; Clerson, P.; Lévy, V. The use of octagam and gammanorm in immunodeficiency associated with hematological malignancies: A prospective study from 21 French hematology departments. Hematology 2019, 24, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, I.; Buckland, M.; Agostini, C.; Edgar, J.D.M.; Friman, V.; Michallet, M.; Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Quinti, I. Current clinical practice and challenges in the management of secondary immunodeficiency in hematological malignancies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 102, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Giralt, S.; Kerre, T.; Lazarus, H.M.; Mustafa, S.S.; Papanicolaou, G.A.; Reiser, M.; Ria, R.; Vinh, D.C.; Wingard, J.R. Secondary antibody deficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood Rev. 2022, 58, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giralt, S.; Jolles, S.; Kerre, T.; Lazarus, H.M.; Mustafa, S.S.; Papanicolaou, G.A.; Ria, R.; Vinh, D.C.; Wingard, J.R. Recommendations for Management of Secondary Antibody Deficiency in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriadou, S.; Clubbe, R.; Garcez, T.; Huissoon, A.; Grosse-Kreul, D.; Jolles, S.; Henderson, K.; Edmonds, J.; Lowe, D.; Bethune, C. British Society for Immunology and United Kingdom Primary Immunodeficiency Network (UKPIN) consensus guideline for the management of immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2022, 210, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Grullón, J.; Guevara-Hoyer, K.; López, C.P.; de Diego, R.P.; Cortijo, A.P.; Polo, M.; Morales, M.M.; Mandley, E.A.; García, C.J.; Bolaños, E.; et al. Combined Immune Defect in B-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders Is Associated with Severe Infection and Cancer Progression. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, K.L.; Wong, J.; Weinkove, R.; Keegan, A.; Crispin, P.; Stanworth, S.; Morrissey, C.O.; Wood, E.M.; McQuilten, Z.K. Interventions to reduce infections in patients with hematological malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.-M.; Sauer, S.; Klein, S.; Tichy, D.; Benner, A.; Bertsch, U.; Brandt, J.; Kimmich, C.; Goldschmidt, H.; Müller-Tidow, C.; et al. Antibiotic Prophylaxis or Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor Support in Multiple Myeloma Patients Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancers 2021, 13, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagno, N.; Cinetto, F.; Semenzato, G.; Agostini, C. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin in lymphoproliferative disorders and rituximab-related secondary hypogammaglobulinemia: A single-center experience in 61 patients. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, M.; Iliakis, T.; Maltezas, D.; Bitsani, A.; Kalyva, S.; Koudouna, A.; Kotsanti, S.; Petsa, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Kyrtsonis, M.-C.; et al. Efficacy-safety of Facilitated Subcutaneous Immunoglobulin in Immunodeficiency Due to Hematological Malignancies. A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 4187–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Years of professional practice | |

| <5 | 9 |

| 5–10 | 29 |

| 11–15 | 9 |

| >15 | 54 |

| Hospital characteristics | |

| Public hospital | 94 |

| Private hospital | 6 |

| <200 beds | 6 |

| 200–400 beds | 11 |

| >400 beds | 83 |

| Center with immunology consultation | 65 |

| Center with immunology laboratory | 75 |

| Center with protocol for SID | 35 |

| Patients | |

| Center with hematological neoplasms and SID | 100 |

| 0–10 patients/year | 9 |

| 10–20 patients/year | 32 |

| Baseline Immunological Evaluation in the Initial Survey | Consensus | |

|---|---|---|

| Against | In Favor | |

| Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | 0 | 100.0 |

| Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) | 0 | 100.0 |

| Patients with lymphoma | 0 | 100.0 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) recipients | 0 | 100.0 |

| Patients of advanced age/fragile | 47.1 | 52.9 |

| Prophylaxis of Infection | Consensus | |

|---|---|---|

| Against | In Favor | |

| How often do doctors think that patients with hematological malignancies receive active immunization against the following infections: | ||

| ||

| Seasonal influenza and H1N1 | 2.9 | 97.1 |

| Pneumococcus | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 51.4 | 48.6 |

| ||

| Seasonal influenza and H1N1 | 8.6 | 91.4 |

| Pneumococcus | 25.7 | 74.3 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 48.6 | 51.4 |

| ||

| Seasonal influenza and H1N1 | 8.6 | 91.4 |

| Pneumococcus | 28.6 | 71.4 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 51.4 | 48.6 |

| Except for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii and viruses, how often do doctors think that patients receive antibiotic prophylaxis for recurrent infections in: | ||

| 54.3 | 45.7 |

| 57.1 | 42.9 |

| 57.1 | 42.9 |

| How often do you use antibiotic prophylaxis if there is evidence of hypogammaglobulinemia in: | ||

| 71.4 | 28.6 |

| 74.3 | 25.7 |

| 74.3 | 25.7 |

| Use of IVIG | Consensus | |

|---|---|---|

| Against | In Favor | |

| How do you often use IVIG after baseline immunological evaluation? | ||

| 68.6 | 31.4 |

| 77.1 | 22.9 |

| 80.0 | 20.0 |

| How often do doctors use IVIG if there are recurrent infections in: | ||

| 51.4 | 48.6 |

| 68.6 | 31.4 |

| 60.0 | 40.0 |

| How often do doctors use IVIG if there is evidence of hypogammaglobulinemia in: | ||

| 55.9 | 44.1 |

| 73.5 | 26.5 |

| 67.6 | 32.3 |

| Recommendations | Consensus | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline immunological evaluation | ||

| Guidelines are necessary for the management of immunodeficiencies in hematological patients | 100% | |

| In the initial survey of CLL, MM, lymphoma and HSCT recipients | 100% | |

| After recurrent/severe infection when SID is suspected in CLL, MM, lymphoma and HSCT recipients | 100% | |

| In patients with B-cell neoplasms (anamnesis, physical examination, proteins total/electrophoresis) | 100% | |

| Quantification of IgG, IgA and IgM levels when SID is suspected | 100% | |

| Quantification of IgG subclasses when SID is suspected | 77% | |

| Specific antibodies against immunization with protein and polysaccharide antigens when SID is suspected | 83% † | |

| Immunophenotyping subpopulations of T, B, natural killer when SID is suspected | 91% | |

| Chest CT scan in case of suspected SID | 67% † | |

| Auto-antibodies (antinuclear, anti-DNA, anti-phospholipid, anti-platelet, anti-neutrophil, etc.) in case of suspected SID | 72% † | |

| Functional immunological evaluation after recurrent and/or severe infection when SID is suspected | In patients with CLL | 74% |

| In patients with MM | 77% | |

| In patients with lymphoma | 78% † | |

| Prophylaxis of infection | ||

| Patients with CLL should receive active immunization against | Seasonal influenza and H1N1 and pneumococcus | 97% |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 94% | |

| HAV and HBV (in sero-negative patients) | 91% | |

| Patients with MM should receive active immunization against | Seasonal influenza and H1N1 and pneumococcus | 97% |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 94% | |

| HAV and HBV (in sero-negative patients) | 91% | |

| Patients with lymphoma should receive active immunization against | Seasonal influenza and H1N1 | 97% |

| Pneumococcus | 94% | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 91% | |

| HAV and HBV (in sero-negative patients) | 86% | |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis after baseline evaluation should be established | In patients with CLL | 94% * |

| In patients with MM | 94% * | |

| In patients with lymphoma | 88% * | |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis in cases of recurrent infection (excluding Pneumocystis carinii and viruses) should be established | In patients with CLL | 89% † |

| In patients with MM | 89% † | |

| In patients with lymphoma | 89% † | |

| Use of intravenous IgG (IVIG) | ||

| If there are recurrent infections | In patients with CLL | 78% † |

| In patients with MM | 78% † | |

| In patients with lymphoma | 72% † | |

| In the presence of hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with lymphoma | 82% * | |

| Requirement to have a clinical protocol for the management of IVIG in patients with SID | 94% | |

| Start treatment with IVIG at a dose of 400 mg/kg every 4 weeks for 12 months in the candidate patient | 80% | |

| Personalize the IVIG dose | 91% | |

| The aim of maintenance therapy is to maintain IgG trough levels between 500 and 700 mg/dL in patients with recurrent infections and malignant blood disease | 94% | |

| Early decision on IVIG replacement therapy to prevent the development or progression of bronchiectasis | 91% | |

| Need for monitoring of IgG levels to determine the correct dose of IVIG | 86% | |

| Follow-up and monitoring of patients receiving IVIG therapy | ||

| Monitoring of IgG levels | 97% | |

| Monitoring of the clinical efficacy of IVIG (decrease in and/or absence of bacterial and viral infections) | 97% | |

| Monitoring of IgG levels | Every 3 months | 83% |

| Every 6 months | 77% | |

| Monitoring of the clinical efficacy of IVIG therapy | Every 3 months | 86% |

| Every 6 months | 83% | |

| Discontinuation of treatment with IVIG after recovery of IgG levels | 77% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boqué, C.; Sánchez-Ramón, S.; Córdoba, R.; Moreno, C.; Cabezudo, E. Current Approach in the Management of Secondary Immunodeficiency in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Spanish Expert Consensus Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6356. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196356

Boqué C, Sánchez-Ramón S, Córdoba R, Moreno C, Cabezudo E. Current Approach in the Management of Secondary Immunodeficiency in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Spanish Expert Consensus Recommendations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(19):6356. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196356

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoqué, Concepción, Silvia Sánchez-Ramón, Raúl Córdoba, Carol Moreno, and Elena Cabezudo. 2023. "Current Approach in the Management of Secondary Immunodeficiency in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Spanish Expert Consensus Recommendations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 19: 6356. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196356

APA StyleBoqué, C., Sánchez-Ramón, S., Córdoba, R., Moreno, C., & Cabezudo, E. (2023). Current Approach in the Management of Secondary Immunodeficiency in Patients with Hematological Malignancies: Spanish Expert Consensus Recommendations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(19), 6356. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196356