Younger Age and Parenchyma-Sparing Surgery Positively Affected Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. HRQoL Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

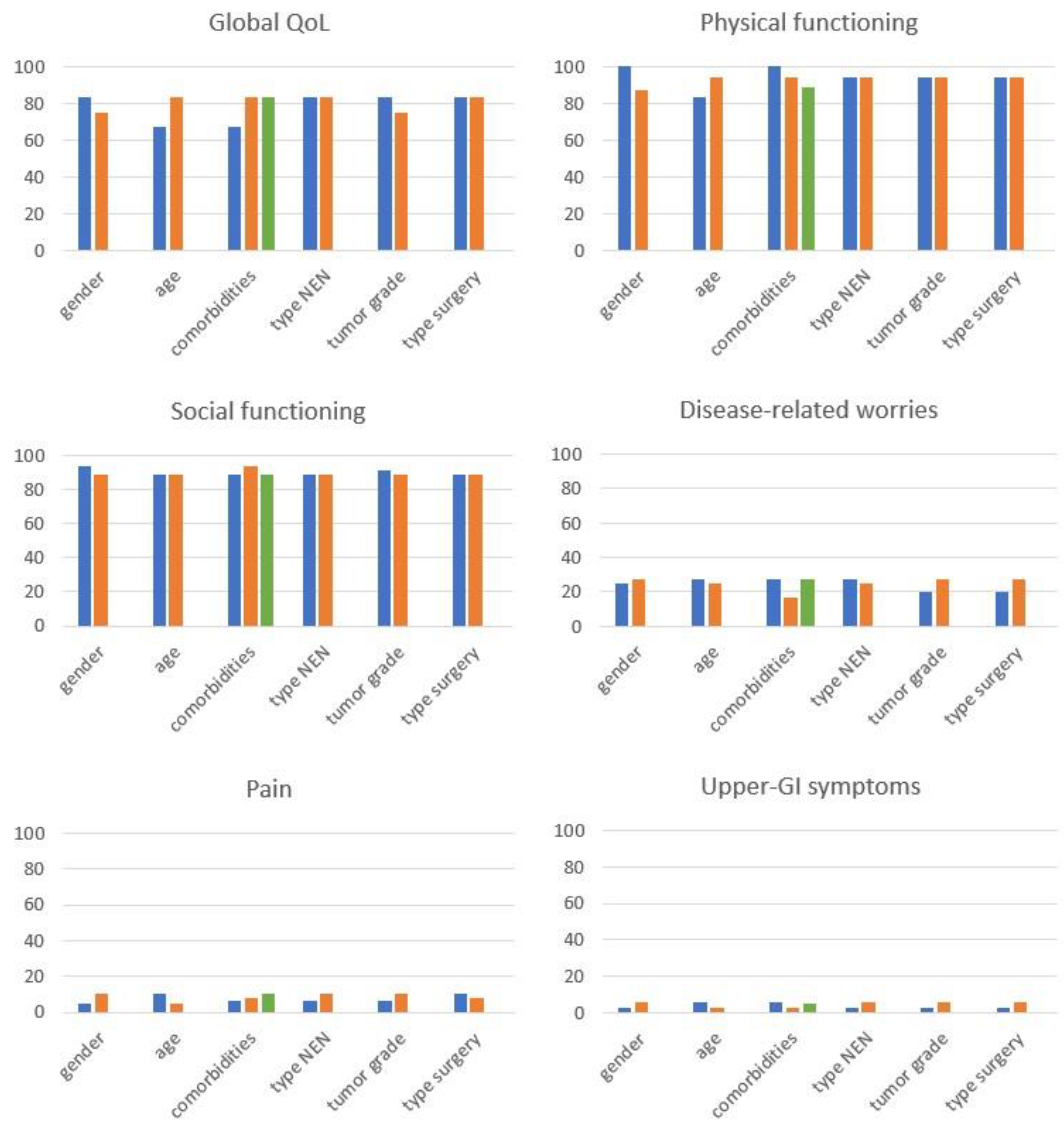

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khanna, L.; Prasad, S.R.; Sunnapwar, A.; Kondapaneni, S.; Dasyam, A.; Tammisetti, V.S.; Salman, U.; Nazarullah, A.; Katabathina, V.S. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: 2020 Update on Pathologic and Imaging Findings and Classification. Radiographics 2020, 40, 1240–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, A.; Shen, C.; Halperin, D.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Shih, T.; Yao, J.C. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öberg, K.; Knigge, U.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Perren, A.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine gastro-entero-pancreatic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. 7), vii124–vii130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, D.F. Measuring quality of life in palliative care. Semin. Oncol. 1995, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caplin, M.E.; Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Phan, A.T.; Raderer, M.; Sedláčková, E.; Cadiot, G.; Wolin, E.M.; Capdevila, J.; Wall, L.; et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Carmona-Bayonas, A.; Martín-Pérez, E.; Crespo, G.; Serrano, R.; Llanos, M.; Villabona, C.; García-Carbonero, R.; Aller, J.; Capdevila, J.; et al. Health-related quality of life in well-differentiated metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Unger, N.; Borbath, I.; Ricci, S.; Hwang, T.L.; Brechenmacher, T.; Park, J.; Herbst, F.; Beaumont, J.L.; Bechter, O. Safety and QOL in Patients with Advanced NET in a Phase 3b Expanded Access Study of Everolimus. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, J.K.; Punia, P.; Faluyi, O.; Frilling, A.; Meyer, T.; Saharan, R.; Valle, J.W. Observational Study to Assess Quality of Life in Patients with Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Receiving Treatment with Everolimus: The OBLIQUE Study (UK Phase IV Trial). Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, J.J.; Kwekkeboom, D.J.; Krenning, E.P. Quality of life in patients with gastroenteropancreatic tumors treated with [177Lu-DOTA0, Tyr3]octreotate. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2724–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, M.; Mücke, M.; Mahlberg, L.; Essler, M.; Cuhls, H.; Radbruch, L.; Conrad, R.; Ahmadzadehfar, H. Improving quality of life in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor following peptide receptor radionuclide therapy assessed by EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, C.; Buxbaum, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Nilica, B.; Scarpa, L.; Holzner, B.; Virgolini, I.; Gamper, E.M. Quality of Life in Patients with Metastatic Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Receiving Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy: Information from a Monitoring Program in Clinical Routine. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronde, E.M.; Heidsma, C.M.; Eskes, A.M.; Schopman, J.E.; Nieveen van Dijkum, E.J.M. Health-related quality of life and treatment effects in patients with well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, C.; Tallentire, C.W.; Ramage, J.K.; Srirajaskanthan, R.; Leeuwenkamp, O.R.; Fountain, D. Quality of life in patients with gastroenteropancreatic tumours: A systematic literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 3686–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EORTC Quality of Life. Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires/ (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadegarfar, G.; Friend, L.; Jones, L.; Plum, L.M.; Ardill, J.; Taal, B.; Larsson, G.; Jeziorski, K.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Ramage, J.K.; et al. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-GINET21 questionnaire for assessing quality of life of patients with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.H.; Larsson, G.; Ardill, J.; Friend, E.; Jones, L.; Falconi, M.; Bettini, R.; Koller, M.; Sezer, O.; Fleissner, C.; et al. Development of a disease-specific Quality of Life questionnaire module for patients with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, A.; Karanicolas, P.; Mchir, J.; Bottomley, A.; Allen, P.; Gonen, M. Psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-PAN26 pancreatic cancer module for assessing health related quality of life after pancreatic resection. JOP 2017, 18, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fayers, P.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bjordal, K.; Groenvold, M.; Curran, D.; Bottomley, A. Scoring procedures. In The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual, 3rd ed.; EORTC Quality of Life Group Publications: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; pp. 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Milanetto, A.C.; Nordenström, E.; Sundlöv, A.; Almquist, M. Health-Related Quality of Life After Surgery for Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumours. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnappel, E.N.; Dijksterhuis, W.P.M.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Augustinus, S.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Molenaar, I.Q.; Busch, O.R.; Besselink, M.G.; Wilmink, J.W.; et al. The fear of cancer recurrence and progression in patients with pancreatic cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4879–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, A.; Kosaka, H.; Kaibori, M.; Higashi, T.; Ogawa, A. Activities of daily living after surgery among older patients with gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancers: A retrospective observational study using nationwide health services utilisation data from Japan. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, R.; Scandurra, C.; Maldonato, N.M.; Dolce, P.; Dipietrangelo, G.G.; Centello, R.; Di Vito, V.; Giannetta, E.; Isidori, A.M.; Lenzi, A.; et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms: A two-wave longitudinal study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 2193–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, S.; Boninsegna, L.; Partelli, S.; Falconi, M. Parenchyma-sparing resections for pancreatic neoplasms. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 2010, 17, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beger, H.G.; Mayer, B.; Vasilescu, C.; Poch, B. Long-term Metabolic Morbidity and Steatohepatosis Following Standard Pancreatic Resections and Parenchyma-sparing, Local Extirpations for Benign Tumor: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, T.; De Pastena, M.; Paiella, S.; Marchegiani, G.; Landoni, L.; Festini, M.; Ramera, M.; Marinelli, V.; Casetti, L.; Esposito, A.; et al. Pancreatic Enucleation Patients Share the Same Quality of Life as the General Population at Long-Term Follow-Up: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e609–e616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, N.W.; Fayers, P.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bottomley, A.; de Graeff, A.; Groenvold, M.; Gundy, C.; Koller, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; et al. EORTC QLQC30 tables of reference values. In The EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values Manual; EORTC Quality of Life Group Publications: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; pp. 14–294. [Google Scholar]

| Global QoL | |||||||||||||||

| 29 | 30 | ||||||||||||||

| Functional Scales | |||||||||||||||

| PF | EF | SX | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 42 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 55 | 56 | 51 | |||

| SF | RF | HCS | CF | ||||||||||||

| 26 | 27 | 42 | 44 | 49 | 52 | 6 | 7 | 53 | 54 | 50 | 20 | 25 | |||

| Symptom Scales | |||||||||||||||

| PA | TR | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | 19 | 31 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 48 | 38 | 43 | 50 | 39 | 40 | ||||

| LGI | OS | ||||||||||||||

| 16 | 17 | 35 | 36 | 32 | 40 | 46 | 47 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 18 | |||

| UGI | FI | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 39 | 44 | 45 | 28 | ||||

| ED | DRWs | BI | |||||||||||||

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 41 | 43 | 47 | 41 | 51 | 48 | 49 | 45 | 46 | ||||

| At the Time of Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 41 (39.4) |

| Female | 63 (60.6) | |

| Type of NEN, n (%) | Functioning 1 | 44 (42.3) |

| Nonfunctioning | 60 (57.7) | |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | G1 | 73 (75.3) |

| G2 | 24 (24.7) | |

| N/A | 7 | |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | Parenchyma-sparing resection 2 | 48 (46.1) |

| Standard resection 3 | 56 (53.9) | |

| MEN-1 syndrome, n (%) | Yes | 18 (17.3) |

| No | 86 (82.7) | |

| At the time of the study | ||

| Age (years) | median (range) | 63 (20–90) |

| Under 65 | 53 (51.0) | |

| More/equal 65 | 51 (49.0) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | No | 13 (12.6) |

| Single | 24 (23.3) | |

| Multiple | 66 (64.1) | |

| N/A | 1 | |

| Tumor burden, n (%) | NED | 91 (87.5) |

| LR | 6 (5.8) | |

| DM | 7 (6.7) | |

| Systemic and/or locoregional treatments, n (%) | Current | 5 (4.8) |

| Previous | 2 (1.9) | |

| No | 97 (93.3) | |

| SSA therapy, n (%) | Current | 10 (9.6) |

| Previous | 2 (1.9) | |

| No | 92 (88.5) | |

| New surgery, n (%) | Yes 4 | 6 (5.8) |

| No | 98 (94.2) | |

| Pancreatic function, n (%) | New onset diabetes mellitus | 5 (4.8) |

| Exocrine insufficiency | 5 (4.8) | |

| Exocrine/Endocrine insufficiency | 8 (7.7) | |

| Normal | 86 (82.7) | |

| Outcome Variable (Missing Data) 1 | Median Value | IQR | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global QoL | 83.3 | 58.3–100 | 5.6 | 100 |

| Functional scales | ||||

| Physical functioning (0.2%) | 94.4 | 77.8–100 | 5.6 | 100 |

| Role functioning (0.5%) | 100 | 83.3–100 | 0.0 | 100 |

| Emotional functioning (1.2%) | 91.7 | 75.0–100 | 25.0 | 100 |

| Cognitive functioning | 100 | 83.3–100 | 16.7 | 100 |

| Social functioning (2.9%) | 88.9 | 77.8–94.4 | 27.8 | 100 |

| Healthcare satisfaction (8.3%) | 77.8 | 66.7–100 | 0.0 | 100 |

| Sexuality (23.7%) | 100 | 100–100 | 0.0 | 100 |

| Symptomatic scales | ||||

| Disease-related worries (10.2%) | 26.7 | 13.3–33.3 | 8.0 | 80.0 |

| Body image (8.4%) | 8.3 | 0.0–16.7 | 0.0 | 66.7 |

| Financial difficulties (1%) | 0.0 | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0 | 100 |

| Pain (1%) | 9.2 | 0.0–19.0 | 0.0 | 80.9 |

| Endocrine symptoms (1.3%) | 0.0 | 0.0–16.7 | 0.0 | 88.9 |

| Treatment-related symptoms (35.6%) | 0.0 | 0.0–11.1 | 0.0 | 44.4 |

| Lower-GI symptoms (0.4%) | 8.3 | 4.2–20.8 | 0.0 | 62.5 |

| Upper-GI symptoms (1%) | 3.9 | 0.0–9.1 | 0.0 | 66.7 |

| Other symptoms 2 (0.2%) | 13.3 | 0.0–26.7 | 0.0 | 73.3 |

| Functional Scales | Symptomatic Scales | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global QoL | Physical Functioning | Social Functioning | Disease-Related Worries | Pain | Upper-GI Symptoms | |||||||

| AME (95% CI) | p Value | AME (95% CI) | p Value | AME (95% CI) | p Value | AME (95% CI) | p Value | AME (95% CI) | p Value | AME (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.17) | 0.082 | 0.11 (0.03, 0.19) | 0.007 | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.17 | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.03) | 0.211 | −0.08 (−0.14, −0.02) | 0.012 | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.02) | 0.351 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| >/=65 y | −0.12 (−0.21, −0.03) | 0.006 | −0.12 (−0.2, −0.04) | 0.003 | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) | 0.1 | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.13) | 0.149 | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14) | 0.034 | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.082 |

| <65 y | ||||||||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||||

| No | ||||||||||||

| Single | 0.06 (−0.1, 0.23) | 0.44 | −0.03 (−0.18, 0.12) | 0.712 | 0.02 (−0.11, 0.15) | 0.792 | −0.05 (−0.16, 0.06) | 0.352 | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.09) | 0.304 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | 0.607 |

| Multiple | −0.05 (−0.19, 0.09) | 0.499 | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.02) | 0.105 | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04) | 0.236 | 0.05 (−0.05, 0.16) | 0.331 | 0.1 (0.04, 0.15) | 0.002 | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | 0.223 |

| Type of NEN | ||||||||||||

| NF | −0.02 (−0.11, 0.07) | 0.718 | 0 (−0.08, 0.08) | 0.989 | −0.03 (−0.1, 0.04) | 0.399 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.11) | 0.381 | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.737 | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) | 0.346 |

| F | ||||||||||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||||||

| G2 | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.17) | 0.267 | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.08) | 0.794 | 0 (−0.08, 0.08) | 0.963 | −0.02 (−0.1, 0.66) | 0.65 | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.04) | 0.339 | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.03) | 0.61 |

| G1 | ||||||||||||

| Type of surgery | ||||||||||||

| Limited | 0.07 (−0.02, 0.16) | 0.141 | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17) | 0.037 | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16) | 0.012 | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) | 0.108 | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.05) | 0.693 | −0.04 (−0.08, 0) | 0.047 |

| Standard | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milanetto, A.C.; Armellin, C.; Brigiari, G.; Lorenzoni, G.; Pasquali, C. Younger Age and Parenchyma-Sparing Surgery Positively Affected Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206529

Milanetto AC, Armellin C, Brigiari G, Lorenzoni G, Pasquali C. Younger Age and Parenchyma-Sparing Surgery Positively Affected Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(20):6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206529

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilanetto, Anna Caterina, Claudia Armellin, Gloria Brigiari, Giulia Lorenzoni, and Claudio Pasquali. 2023. "Younger Age and Parenchyma-Sparing Surgery Positively Affected Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 20: 6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206529

APA StyleMilanetto, A. C., Armellin, C., Brigiari, G., Lorenzoni, G., & Pasquali, C. (2023). Younger Age and Parenchyma-Sparing Surgery Positively Affected Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(20), 6529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12206529