Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most diagnosed cancers among women. Its effects on the cognitive and wellbeing domains have been widely reported in the literature, although with inconsistent results. The central goal of this review was to identify, in women with breast cancer, the main memory impairments, as measured by objective and subjective tools and their relationship with wellbeing outcomes. The systematic literature search was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases. The selected studies included 9 longitudinal and 10 cross-sectional studies. Although some studies included participants undergoing multimodal cancer therapies, most focused on chemotherapy’s effects (57.89%; n = 11). The pattern of results was mixed. However, studies suggested more consistently working memory deficits in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. In addition, some associations have been identified between objective memory outcomes (verbal memory) and wellbeing indicators, particularly depression and anxiety. The inconsistencies in the results could be justified by the heterogeneity of the research designs, objective and subjective measures, and sample characteristics. This review confirms that more empirical evidence is needed to understand memory impairments in women with breast cancer. An effort to increase the homogeneity of study methods should be made in future studies.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common diagnoses worldwide, registering an incidence of 2,261,419 new cases in 2020 [1]. With technological and scientific advances in early diagnosis and cancer treatments [2], there is growing interest in the long-term side effects of this disease. Cognitive difficulties are recurrent symptoms reported by breast cancer patients, and they can persist for several years after the end of treatment, resulting in substantial adverse physical and psychosocial consequences [3]. Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) is a term used to describe cognitive impairment during and after cancer diagnosis and treatment [4,5].

Research has documented that from 17% to 75% of women diagnosed with breast cancer experience CRCI in domains related to attention, concentration, memory, and executive functions from 6 months to 20 years after chemotherapy [6,7]. Although these cognitive changes are widely considered to be a side effect of chemotherapy, sometimes referred to as “chemobrain” or “chemofog”, the body of evidence has already highlighted the potential effects of other cancer treatments (e.g., hormonal therapies, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy), pathophysiological mechanisms [8,9], and psychosocial factors [10]. In this sense, the development of CRCI seems to be multifactorial, but the identification of its causal factors has not yet been fully clarified.

In addition, previous studies have also pointed to controversy regarding the relationship between objective cognitive problems, assessed by neuropsychological tests, and subjective cognitive problems (also known as cognitive complaints), assessed by self-report measures. Cognitive complaints in breast cancer survivors are not always associated with objective cognitive changes [11], similar to other populations, e.g., older adults [12]. According to the International Cognition and Cancer Task Force (ICCTF) [7], it is recommended that cognitive functions, such as learning, memory, processing speed, and executive functions, be assessed using objective measures. However, some authors argue that self-report measures can better detect subtle declines in cognitive functioning than neuropsychological tests [10,13]. The design heterogeneity of the studies, the lack of consistency in the cognitive functions assessed, and the measures applied could contribute to the absence of patterns and maintain uncertainty about the cognitive deficits reported by breast cancer patients [9].

Previous review works have presented a broad scope summarizing CRCI-related results [5,6,9,10] that more consistently point to impaired performance on memory tasks as well as memory complaints in breast cancer patients [9]. Meta-analyses have revealed the largest effects in terms of changes in memory and executive functions when compared to other cognitive domains, such as reason and perception [14]. Chemotherapy seems to be one of the therapies with the most pronounced impact, particularly on verbal working memory. Still, a more restricted evidence synthesis is needed since the current picture is inconclusive [3]. For this reason, filling a gap in the literature, this review aimed to systematize the existing evidence on specific memory deficits in breast cancer survivors (measured by objective and subjective tools), identifying guidelines for practice and future research.

Furthermore, there has been growing interest in understanding the relationship between memory outcomes and wellbeing (usually measured by self-assessment instruments). Although it is well established that breast cancer impacts physical and psychological functioning, there is a lack of studies summarizing the relationships between memory deficits and patients’ perceived wellbeing. The limited evidence available seems to suggest a bidirectional relationship between cognitive functioning and indicators of impaired wellbeing, such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue, which can occur simultaneously as a risk factor or a consequence of potential deficits [3,5,9,10]. The current work aimed to systematize not only memory impairments in women with breast cancer but also their relationship with wellbeing indicators, specifically with psychological (depressive symptoms, anxiety, and (di)stress) and physical (physical functioning and fatigue) wellbeing.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [15].

2.1. Elegibility Criteria

The PICO framework was used to define the study inclusion criteria. Studies were included in this review if they (i) involved breast cancer patients (18–75 years old at enrollment) in the active or disease-free phase; (ii) assessed cancer-related memory deficits using subjective and/or objective measures; (iii) explored the association between memory outcomes and psychological (depressive symptoms, anxiety and (di)stress)) and physical (physical functioning and fatigue) wellbeing; (iv) were written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish; and (v) were published in a peer-reviewed journal between 2000 and 2022. Studies involving patients with brain metastases and/or a history of comorbidity with neurological and/or psychiatric conditions were excluded. Protocols, literature reviews, meta-analyses, validation studies, book chapters, commentaries, unpublished articles, and conference abstracts were also excluded.

2.2. Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest. The first search was performed in January 2023, and then it was re-run in May 2023 to identify possible further studies. The key terms used were ‘cancer’, ‘neoplasm’, ‘tumour’, ‘carcinom’ and ‘memory’, ‘mnesic’, ‘stress’, ‘anxiety’ OR ‘depression’, ‘physical’, and ‘well-being’). The search was adapted for the 3 databases, and OR and AND functions were used to combine the above terms. Specific filters related to restrictions on publication date, language, and/or document type were applied whenever possible.

2.3. Selection Process and Data Extraction

An independent screening of the titles and abstracts obtained from the database searches was carried out by two researchers (P.F.S.R. and A.B.), and a list of studies for full-text examination was produced after removing the duplicates. This initial screening was conducted using a semiautomation tool—Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third review author (P.B.A.). Next, the pair of raters independently extracted the full texts of the potentially eligible articles and evaluated them for inclusion. Studies whose inclusion or exclusion could not be determined with certainty based on the information in the title and abstract were also acquired for further examination. For each included study, information was gathered using a predesigned data extraction form including the following categories: (i) study characteristics such as “author”, “country”, “study design”, and “sample size”; (ii) patient characteristics namely “mean age”, “sex”, ”time since diagnosis”, and “cancer treatments”; and (ii) “assessment measures”, “main memory deficits”, and their relationship with wellbeing indicators.

2.4. Quality Appraisal

Two review authors (P.F.R.S. and A.B.) independently appraised the quality of eligible studies based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Statistics Assessment and Review Instruments critical appraisal checklists for analytical cross sectional studies and cohort studies [16,17]. Each item on these checklists was appraised as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable”. Any disagreements between the revisions were resolved by discussion between all the coauthors, when necessary. The study quality was assessed based on the information available in the papers.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

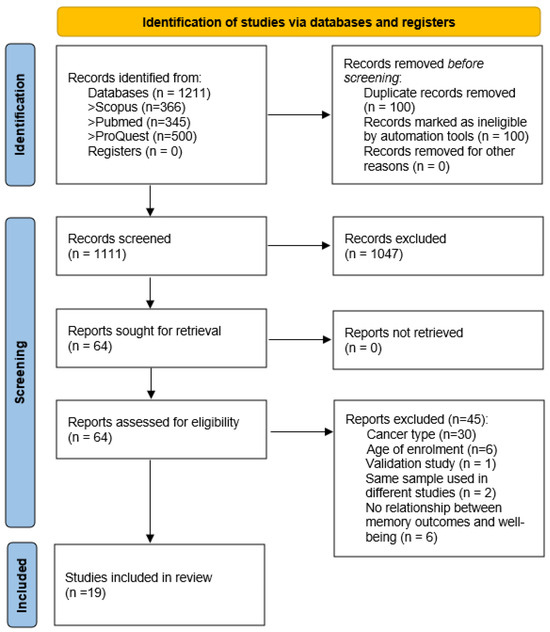

A total of 1211 articles were identified from the electronic databases. After removing duplicates (n = 100), 1111 were screened based on title and abstract. Only 64 records were potentially eligible, and the review team retrieved and analyzed their full texts. Of these, 45 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Most of the excluded studies involved several cancer types. Two eligible articles that used the same sample in two different publications were also excluded from the results analysis [18,19]. Thus, 19 quantitative studies were included in this systematic review. The PRISMA flow diagram of the study search and selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process.

3.2. Study Characteristics

This review included 9 longitudinal and 10 cross-sectional studies published between 2007 and 2022. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. About 36.84% of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 7). This was also a field of interest in countries such as France (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 1) and Germany (n = 1). The sample sizes included in the studies ranged from 38 [20] to 1477 [21] and involved only women diagnosed with breast cancer. The mean age of the participants ranged from 49 [22] to 62 [23] years old. About 57.89% (n = 11) of the studies were focused on survivors undergoing chemotherapy [20,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Table 1.

Characteristics and results of the included studies.

3.3. Memory Assessment: Objective and Subjective Measures

Neuropsychological testing provides objective assessments of memory outcomes. However, the assessment protocols used in the studies included in this review revealed high heterogeneity. Sixteen out of 19 included studies (84.2%) used cognitive test batteries. Subtests of objective measures, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) and Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-R/WMS-III/WMS-IV), were most frequently applied. The digit span was the most common test among the different protocols (n = 7) [24,25,29,31,35,36,38] being used to assess short-term and/or working memory. Visual memory was assessed consistently through the visual reproduction subtests of the WMS (n = 3) [20,23,31]. Three studies also used the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test to assess verbal memory [23,24,35]. Subjective memory complaints were also assessed in 42.1% of studies (n = 8) [21,25,26,27,30,33,34,38]. Only scales such as the Attentional Function Index (n = 2) [33,34] and the Patient’s Own Functioning Assessment Inventory (n = 2) [26,30] were used in more than one study. However, these are more general measures that assess other cognitive functions besides memory (Table 1 details all the objective and subjective measures used).

3.4. Effect of Breast Cancer and Associated Treatments on Memory

Studies showed mixed results concerning cancer treatments’ effects on breast cancer patients’ memory. Six out of the nine included longitudinal studies explored the impact of chemotherapy on memory [20,25,26,28,31,33].

Longitudinal data obtained using objective neuropsychological measures (n = 3) showed that performance on tasks involving short-term memory [25] and working memory [28,33] decreased significantly after chemotherapy treatment. One record suggested that verbal working memory impairment remained even 7 months after treatment [33]. Objective outcomes regarding verbal memory were inconsistent. Two studies suggested that cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy showed no differences in verbal memory compared to a healthy control group [20], nor compared to patients who were prechemotherapy [22]. However, a longitudinal study by Vearncombe et al. [31] demonstrated worse performance on verbal memory tasks 4 weeks after administering the last course of chemotherapy.

Regarding visual memory, the longitudinal studies (n = 2) did not suggest a negative impact of chemotherapy, although limited by the small sample size. Ando-Tanabe et al. [20] found no differences between the chemotherapy group and a control group, and Vearncombe et al. [31] demonstrated improvements in visual memory (e.g., visual reproduction, visual reproduction delayed, and visual recognition) from pre- to postchemotherapy. Additionally, a cross-sectional study showed that breast cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy had poorer outcomes in prospective memory (d = 0.80) and retrospective memory (immediate recall, d = 0.72; delayed recall, d = 0.77) compared to healthy controls [27]. In turn, Le Run and collaborators [35], focusing on cognition in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant hormonotherapy, showed that this therapeutic did not affect performance on visual and verbal episodic memory and working memory tasks (no changes were registered during one year of follow up).

Assessment of subjective memory complaints (n = 8) through self-report measures also indicated that cancer patients reported more complaints after chemotherapy, which persisted even after one year (d = 0.15) [26]. Perceived impairment in prospective memory increased after chemotherapy treatment [25]. However, a cross-sectional study suggested that prospective and retrospective memory complaints were identical between women undergoing chemotherapy and healthy controls [27], although the results of objective measures were not in the same direction. Despite this, breast cancer survivors had more prospective than retrospective memory complaints (d = 1.12). A recent study also points to increased working memory complaints from the presurgery period to one month after surgery and before any adjuvant treatment [34].

3.5. Relationship between Memory Outcomes and Wellbeing Indicators

Wellbeing was measured through proxy variables, including depressive and anxiety symptoms, distress, perceived stress and worries (psychological wellbeing), physical functioning, and fatigue (physical wellbeing). Symptoms of anxiety and/or depression were most frequently assessed across studies using measures such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] (n = 5) [20,21,22,31,35], State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI] (n = 4) [24,32,36,38]; and Beck Depression Inventory [BDI-II] (n = 3) [26,37,38]. Regarding the relationship between performance on objective memory measures and depressive symptoms, the results are not conclusive. Evidence from four studies supports this association, especially in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors (three out of four studies) [20,24,25]. Poorer performance on logical (r = −0.50; r = −0.77) [20], verbal (r = −0.76) [20], visual (r = −0.25) [23], and short-term memory tasks [25] was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients. More specifically, in the study by Crouch et al. [24], depressive symptoms were a negative predictor of delayed recall in women without recurrence and undergoing chemotherapy (β = −0.23). However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, as five studies did not go in the same direction, suggesting that there was no association between these symptoms and performance on neuropsychological tests [29,30,31,37,38]. In addition, two studies [25,27] consistently suggested that depressive symptoms of chemotherapy patients were associated with more prospective memory complaints (r = 0.47) [27]. Concerning anxiety, studies involving objective cognitive tasks remain mixed. While some studies showed positive associations between performance on verbal memory tests (e.g., long-term recall) and postchemotherapy anxiety symptoms (n = 2) (r = 0.57) [20] (r = 0.40) [22], others showed no association with either state anxiety (n = 3) [30,31] or trait anxiety [38]. Nevertheless, Morel et al. [36] demonstrated that the most anxious breast patients recovered significantly less emotional details than healthy controls. Seven studies also explored the relationship between memory and physical wellbeing [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32]. Three out of seven articles showed (i) a positive correlation between fatigue and performance on immediate memory tasks (r = 0.25) [32]; (ii) a correlation between memory domains and physical symptoms (r = −0.14) [37]; and (iii) an increase in fatigue levels associated with more subjective memory complaints, namely at the level of prospective (r = −0.55) and retrospective memory (r = −0.55) [27]. See more details in Table 1.

3.6. Study Quality Assessment

Table 2 presents the results of the critical appraisal of the studies included in this review. All studies adequately defined the sample inclusion criteria and the study context and included reliable measures. Only one of the studies did not clearly present the cognitive test battery used [28]. Around 52.63% of the studies (n = 10) did not identify or analyze confounding variables. Most studies involved bivariate correlation analyses (52.63%; n = 10) to examine the association between memory outcomes and wellbeing variables. Therefore, although the statistical analyses were appropriate in all studies, more robust statistics are needed to clarify the mixed results found. Three out of nine longitudinal studies (33.33%) did not have complete follow up and did not describe the reasons for loss to follow up [26,28,33]. Moreover, forty-four percent did not identify strategies to deal with dropouts throughout the data-collection process (n = 4) [28,33,34,35].

Table 2.

Critical appraisal of the included studies [16,17].

4. Discussion

The main goal of this systematic review was to identify memory impairments and their relationship with wellbeing indicators in women with breast cancer at the active or disease-free phase. Memory impairments included outcomes measured by objective and subjective tools, and wellbeing was assessed through indicators such as anxiety, depression, (dis)stress, and physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue). To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to focus more narrowly on memory and to summarize its relationship with wellbeing in the context of breast cancer.

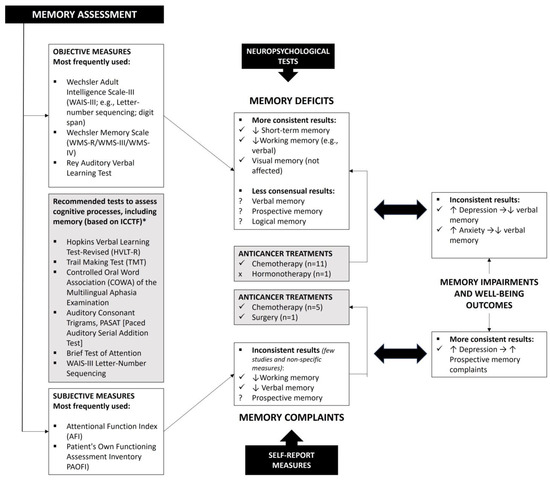

Overall, our review indicated a mixed pattern of results regarding objective memory deficits in cancer patients (see Figure 2). Most of the studies involved women who had undergone chemotherapy, and they consistently suggested impairment of short-term memory and working memory, as previously indicated in the review study by Ahles et al. [6]. A longitudinal study conducted by McDonald et al. [39] had already pointed out that frontal lobe hyperactivation for working-memory tasks decreased 1 month postchemotherapy and a return to pretreatment hyperactivation at 1-year post-treatment. Interestingly, the longitudinal studies included in this review indicated that working memory impairments were maintained over time (up to 7 months), particularly in the verbal domain. The mechanisms involved in cancer-related cognitive impairments are complex and not fully understood. However, previous studies involving breast cancer patients have demonstrated direct brain damage as a consequence of the neurotoxic effects of systematic treatments (e.g., damage to neurons or glial cells, ischemic vascular damage, and a reduced number of proliferative hippocampal cells) that may be the basis of these long-term memory complaints [40]. Evidence also showed that breast cancer survivors had increased levels of inflammation, on average, 20 years after treatment, which is a factor that impacts their cognitive functioning. Therefore, the hypothesis supported in the literature that inflammation is specifically associated with impairment of working memory may explain the results found at this level [41]. Regarding visual memory, the studies with objective measures included in this review consistently demonstrated the absence of impairment after chemotherapy treatments. However, previous meta-analyses, although limited by their broad scope, have found mixed results for both visual and verbal long-term memory (e.g., no differences: Jim et al. [42]; small to medium cumulative effect sizes: Stewart et al. [43]). These results can be explained by the significant variation in the neuropsychological measures used among studies, most of which are not in line with the guidelines of the International Cognition and Cancer Task Force [7]. Furthermore, the possible compensatory activation of other brain areas during cognitive tests in a controlled environment may cover up more subtle deficits, as previously suggested by imaging studies [44].

Figure 2.

Summary of the main results and guidelines for future studies. * Note: International Cognition and Cancer Task Force.

The results of subjective memory complaints are limited by the small number of studies and the lack of specificity of the measures for assessing this cognitive domain. There is some preliminary evidence that breast cancer survivors reported more subjective memory complaints (e.g., long-term verbal memory and working memory) after chemotherapy [25,26,30] and surgery [34]. However, there is still inconsistent data. The literature has suggested that, in general, cancer survivors report cognitive problems but score in the normal range on neuropsychological tests [9]. Our study is not entirely in line with this finding. For example, prospective memory impairments are found in objective measures, which are not visible in self-report questionnaires [27]. The sensitivity of the subjective measures used may also be at the root of this finding. Inconsistencies in memory complaints occur in cancer survivors [45,46] and other populations (e.g., older adults [13]). However, this review suggests the possible correspondence between objective and subjective results regarding impairments in verbal memory and working memory, reinforcing the need to further explore these domains in women with breast cancer. The review study by Bray et al. [11] had already reported marginally significant results regarding the association between self-report measures and neuropsychological tests involving memory assessment. In other contexts (e.g., senior context without disease), for example, subjective memory complaints, have been shown to be predictors of objective declines [47], which can also be analyzed in future studies.

In addition, evidence from this review supports a relationship between memory outcomes and indicators of wellbeing. Cognitive complaints have generally been associated with emotional factors (e.g., depression and anxiety [27]) and fatigue [11], which may justify disparities in results, but not with objective measures. Although the findings of the included studies were inconsistent, some significant associations were found between objective memory impairments and depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Impairment in verbal memory tasks was more frequently associated with psychological distress [20,22,24]. Our results also confirm the significant association between self-reported prospective memory impairments and depressive symptoms and fatigue in women undergoing chemotherapy [25,27]. However, uncertainty remains as to whether memory complaints are related to brain dysfunction due to the treatments, which can lead to affective symptoms, or whether they are a consequence of mood disorder and fatigue [11]. While fatigue has been relatively underexplored in the included studies, the literature has indicated that many cancer patients experience long-term fatigue [8]. Chronic fatigue emerges as a recurring comorbidity in cancer and may lead to memory and cognitive impairments [48]. This close connection presents challenges in pinpointing the origin of the cognitive deficits experienced, potentially contributing to the variability found in this review. Other comorbidities or the severity of treatment-related side effects themselves may be linked to the observed memory deficits and could help elucidate some of the highlighted inconsistencies. Therefore, more studies should be conducted to help clarify these complex relationships, namely by understanding the underlying mechanisms.

The results of the current review should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, this work included studies with heterogeneity of designs (i.e., longitudinal vs. cross-sectional studies) and lack of consistency of cognitive measures applied; additionally, study-design characteristics (i.e., type of control group, timing of assessments), and patient characteristics (i.e., age, education, and time since chemotherapy) seem to be heterogeneous in the selected studies. Also, the included studies incorporated several types of therapeutics, although the most predominant was chemotherapy; finally, around half of the studies did not identify or control for confounding variables, which limits the conclusions drawn.

In future empirical studies, it would be crucial to involve breast cancer patients (i) with a similar time of diagnosis and (ii) other therapeutics, namely hormonotherapy, which has been associated with impairments in various cognitive domains (e.g., attention and executive functions [9]). The specificities of the treatments administered may be decisive in explaining the variability found in this study, especially considering the recent evolution of cancer treatments. For example, targeted therapies with the anti-HER-2 drug trastuzumab emtansine appear to be associated with less cognitive impairment compared to regimens involving chemotherapy [49]. Nevertheless, the evidence is still evolving, and further studies are required with a specific focus on comparing various therapeutic approaches regarding their impact on specific cognitive functions. Moreover, standardized instruments should be used to measure memory and wellbeing indicators; indeed, we can find diverse instruments in the included studies, mainly to measure memory. Longitudinal studies should be preferred to cross-sectional studies, as these designs may provide more rigorous evidence [6,50]. It is also important to reinforce the conduct of research in which a baseline of memory is measured at the time of diagnosis (and before any treatment) to compare with memory assessed after treatments. The assumption that patients do not have intact cognitive abilities before treatment may contribute to inconsistent and inconclusive results in this context. Indeed, the International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommends guidelines to increase the homogeneity of study methods and suggests that “Cross-sectional, post-treatment only studies with appropriate comparison groups might be useful for exploratory analysis, hypothesis-generating, and for proof-of-concept trials, with findings confirmed longitudinally” [7] (p. 704).

5. Conclusions

This work provides an important review of (objective and subjective) memory impairments and their relationship with wellbeing indicators in breast cancer survivors. Although a mixed pattern of results has been found, this review highlights some declines in memory, measured by objective and subjective instruments, as well as some associations with wellbeing indicators such as anxiety and depression. This review highlights the need for additional empirical evidence regarding memory decline in the context of breast cancer. Achieving this necessitates the standardization of methodological procedures and measures used, as well as a deeper understanding of the effects of various therapeutic approaches, particularly the underexplored realm of targeted therapies. This review highlights the need for additional empirical evidence regarding memory decline in the context of breast cancer. Achieving this necessitates the standardization of methodological procedures and measures used, as well as a deeper understanding of the effects of various therapeutic approaches, particularly the underexplored realm of targeted therapies. With this study, our expectation is to provide a reference to assist researchers and professionals in identifying significant memory deficits that should be considered in the assessment of cancer patients, as well as identify gaps in the evidence that should receive greater attention from the scientific community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.S.R., A.B. and P.B.A.; methodology, A.B. and P.F.S.R.; formal analysis, A.B. and P.F.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.F.S.R. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, P.B.A.; supervision, P.B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Portucalense University. PBA was also supported by the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi/UM), School of Psychology, University of Minho, funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (UIDB/01662/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Runowicz, C.D.; Leach, C.R.; Henry, N.L.; Henry, K.S.; Mackey, H.T.; Cowens-Alvarado, R.L.; Cannady, R.S.; Pratt-Chapman, M.L.; Edge, S.B.; Jacobs, L.A.; et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.J.; Oliver, J.S.; Scogin, F. Memory and cancer: A review of the literature. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 28, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, T.S.; Suls, J.; Treviño, M. A Call for a Neuroscience Approach to Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment. Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Országhová, Z.; Mego, M.; Chovanec, M. Long-Term Cognitive Dysfunction in Cancer Survivors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 770413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahles, T.A.; Root, J.C.; Ryan, E.L. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: An update on the state of the science. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3675–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wefel, J.S.; Vardy, J.; Ahles, T.; Schagen, S.B. International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommendations to harmonise studies of cognitive function in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joly, F.; Lange, M.; Dos Santos, M.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Di Meglio, A. Long-Term Fatigue and Cognitive Disorders in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2019, 11, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Joly, F.; Vardy, J.; Ahles, T.; Dubois, M.; Tron, L.; Winocur, G.; De Ruiter, M.B.; Castel, H. Cancer-related cognitive impairment: An update on state of the art, detection, and management strategies in cancer survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hendrix, C.C. Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Breast Cancer Patients: Influences of Psychological Variables. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 5, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, V.J.; Dhillon, H.M.; Vardy, J.L. Systematic review of self-reported cognitive function in cancer patients following chemotherapy treatment. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balash, Y.; Mordechovich, M.; Shabtai, H.; Giladi, N.; Gurevich, T.; Korczyn, A.D. Subjective memory complaints in elders: Depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline? Acta Neurol. Scand. 2013, 127, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre, P. Management of Cancer-related Cognitive Dysfunction-Conceptualization Challenges and Implications for Clinical Research and Practice. US Oncol. 2010, 6, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.D.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Wilson, C.J.; Nettelbeck, T.A. Meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JBI. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional and Cohort Studies: Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Crouch, A.; Champion, V.L.; Von Ah, D. Comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, physical functioning, and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, L.; Collins, B.; Song, X.; Chinneck, A.; Bedard, M.; Verma, S. A pilot study of prospective memory functioning in early breast cancer survivors. Breast 2013, 22, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando-Tanabe, N.; Iwamitsu, Y.; Kuranami, M.; Okazaki, S.; Yasuda, H.; Nakatani, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Watanabe, M.; Miyaoka, H. Cognitive function in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and healthy controls. Breast Cancer 2014, 21, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.M.; Lloyd, G.R.; Awick, E.A.; McAuley, E. Relationship between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity and subjective memory impairment in breast cancer survivors: Role of self-efficacy, fatigue and distress. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.H.; Chen, V.C.; Hsieh, C.C.; Wang, W.K.; Chen, H.M.; Weng, J.C.; Wu, S.I.; Gossop, M. Subjective and objective cognitive functioning among patients with breast cancer: Effects of chemotherapy and mood symptoms. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boele, F.W.; Schilder, C.M.; de Roode, M.L.; Deijen, J.B.; Schagen, S.B. Cognitive functioning during long-term tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Menopause 2015, 22, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, A.; Champion, V.L.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Pressler, S.J.; Huber, L.; Moser, L.R.; Cella, D.; Von Ah, D. Cognitive dysfunction prevalence and associated factors in older breast cancer survivors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ding, K.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chao, H.H.; Li, C.S.; Cheng, H. Depression involved in self-reported prospective memory problems in survivors of breast cancer who have received chemotherapy. Medicine 2019, 98, e15301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, J.D.; Sereika, S.M.; Brufsky, A.M.; McAuliffe, P.F.; McGuire, K.P.; Myers, J.S.; Phillips, M.L.; Ryan, C.M.; Gentry, A.L.; Jones, L.D.; et al. Trajectories of self-reported cognitive function in postmenopausal women during adjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquet, L.; Verma, S.; Collins, B.; Chinneck, A.; Bedard, M.; Song, X. Testing a novel account of the dissociation between self-reported memory problems and memory performance in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilling, V.; Jenkins, V. Self-reported cognitive problems in women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2007, 11, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, B.J.; Jim, H.S.L.; Eisel, S.L.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Scott, S.B. Cognitive performance of breast cancer survivors in daily life: Role of fatigue and depressed mood. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2174–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardy, J.L.; Stouten-Kemperman, M.M.; Pond, G.; Booth, C.M.; Rourke, S.B.; Dhillon, H.M.; Dodd, A.; Crawley, A.; Tannock, I.F. A mechanistic cohort study evaluating cognitive impairment in women treated for breast cancer. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019, 13, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vearncombe, K.J.; Rolfe, M.; Wright, M.; Pachana, N.A.; Andrew, B.; Beadle, G. Predictors of cognitive decline after chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2009, 15, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ah, D.; Tallman, E.F. Perceived cognitive function in breast cancer survivors: Evaluating relationships with objective cognitive performance and other symptoms using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-cognitive function instrument. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.S.; Zhang, M.; Askren, M.K.; Berman, M.G.; Peltier, S.; Hayes, D.F.; Therrien, B.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; Cimprich, B. Cognitive dysfunction and symptom burden in women treated for breast cancer: A prospective behavioral and fMRI analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017, 11, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.S.; Visovatti, M.A.; Sohn, E.H.; Yoo, H.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.S. Impact of changes in perceived attentional function on postsurgical health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients awaiting adjuvant treatment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Rhun, E.; Delbeuck, X.; Lefeuvre-Plesse, C.; Kramar, A.; Skrobala, E.; Pasquier, F.; Bonneterre, J. A phase III randomized multicenter trial evaluating cognition in post-menopausal breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant hormonotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 152, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, N.; Dayan, J.; Piolino, P.; Viard, A.; Allouache, D.; Noal, S.; Levy, C.; Joly, F.; Eustache, F.; Giffard, B. Emotional specificities of autobiographical memory after breast cancer diagnosis. Conscious. Cogn. 2015, 35, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyk, K.; Bower, J.E.; Crespi, C.M.; Petersen, L.; Ganz, P.A. Cognitive function following breast cancer treatment and associations with concurrent symptoms. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkner, J.; Weymar, M.; Löw, A.; Hamm, C.; Struck, A.M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Hamm, A.O. Cognitive functioning and emotion processing in breast cancer survivors and controls: An ERP pilot study. Psychophysiology 2017, 54, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.C.; Conroy, S.K.; Ahles, T.A.; West, J.D.; Saykin, A.J. Alterations in brain activation during working memory processing associated with breast cancer and treatment: A prospective functional MRI study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2500–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; He, X.; Tao, L.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Zhu, C.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, B.; et al. The Working Memory and Dorsolateral Prefrontal-Hippocampal Functional Connectivity Changes in Long-Term Survival Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Tamoxifen. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Willik, K.D.; Koppelmans, V.; Hauptmann, M.; Compter, A.; Ikram, M.A.; Schagen, S.B. Inflammation markers and cognitive performance in breast cancer survivors 20 years after completion of chemotherapy: A cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, H.S.; Phillips, K.M.; Chait, S.; Faul, L.A.; Popa, M.A.; Lee, Y.H.; Hussin, M.G.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Small, B.J. Meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in breast cancer survivors previously treated with standard-dose chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3578–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Bielajew, C.; Collins, B.; Parkinson, M.; Tomiak, E. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 20, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple, A.C.; Schroeder, M.P.; Ryals, A.J.; Wagner, L.I.; Cella, D.; Shih, P.A.; Reilly, J.; Penedo, F.J.; Voss, J.L.; Wang, L. Hippocampal functional connectivity is related to self-reported cognitive concerns in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Neuroimage Clin. 2018, 20, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, K.; Hunter, A.M.; Ercoli, L.; Petersen, L.; Leuchter, A.F.; Ganz, P.A. Evaluating cognitive complaints in breast cancer survivors with the FACT-Cog and quantitative electroencephalography. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 166, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veal, B.M.; Scott, S.B.; Jim, H.S.L.; Small, B.J. Subjective cognition and memory lapses in the daily lives of breast cancer survivors: Examining associations with objective cognitive performance, fatigue, and depressed mood. Psychooncology 2023, 32, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, S.L.; Reid, E.; Whitfield, P.; Moustafa, A.A. Subjective memory complaints as a predictor of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Discov. Psychol. 2022, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusin, A.; Seymour, C.; Cocchetto, A.; Mothersill, C. Commonalities in the Features of Cancer and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS): Evidence for Stress-Induced Phenotype Instability? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, J.; Torregrosa, M.D.; Cauli, O. Cognitive Functions under Anti-HER2 Targeted Therapy in Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.E.E.; Jung, S.O.; Lee, D.; Abraham, I. Neuropsychological Effects of Chemotherapy: Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies on Objective Cognitive Impairment in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, E159–E168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).