Assessing the Efficacy of the Modified SEGA Frailty (mSEGA) Screening Tool in Predicting 12-Month Morbidity and Mortality among Elderly Emergency Department Visitors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collected

2.3. Ethical and Legal Aspects

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Institutionalization at 12 Months

3.3. Initiation of Home Care at 12 Months

3.4. Emergency Department Readmissions at 12 Months

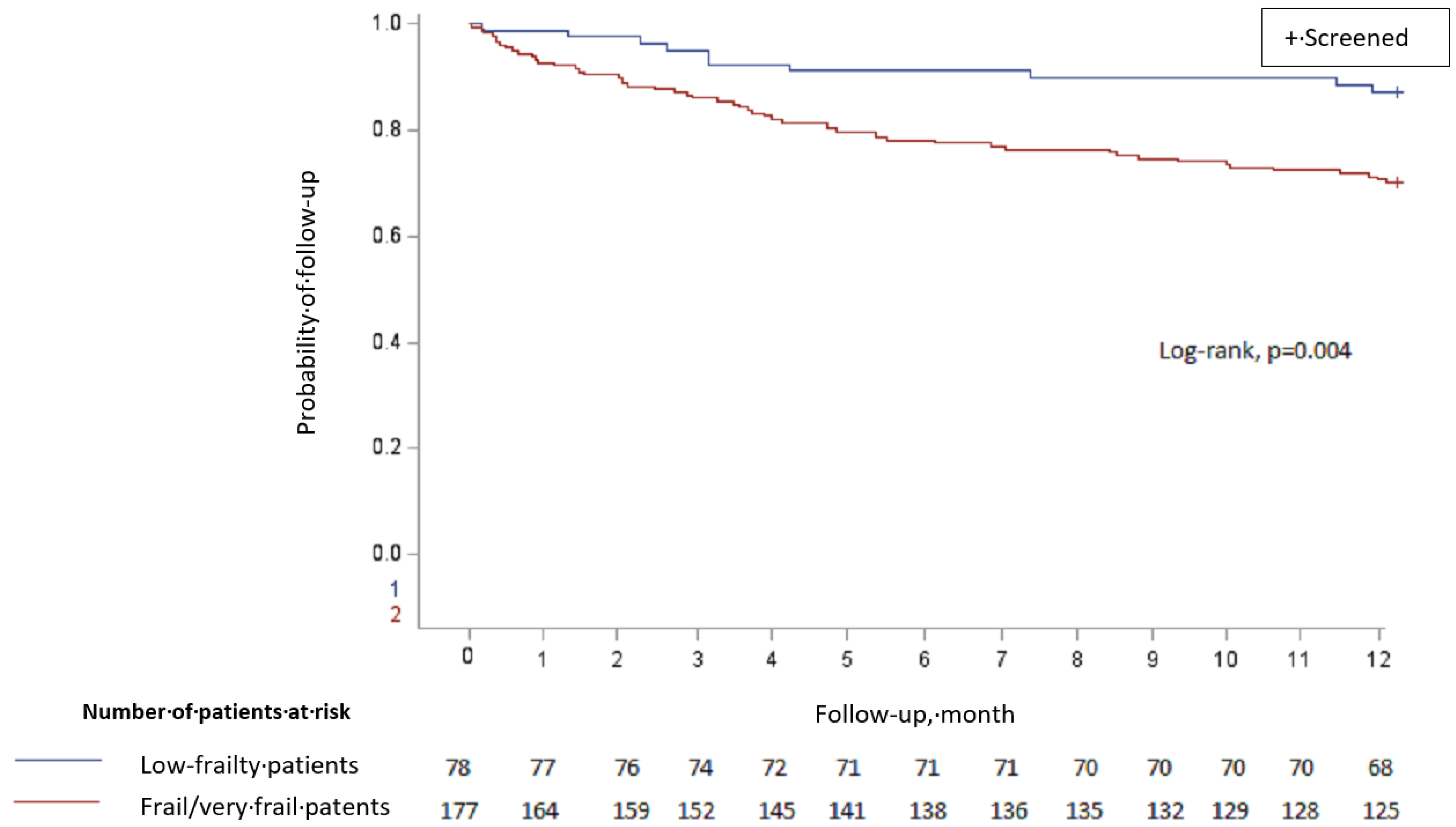

3.5. Death at 12 Months

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gautier, C. Près de 2,000,000 Habitants en Haute-Normandie en 2040; AVAL n°100; L’Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques: Paris, France, 2010.

- Le Conte, P.; Baron, D. Particularités sémiologiques de la personne âgée dans le service d’accueil et d’urgence. In Actualités en Réanimation et Urgences; Arnette-Blackwell: Paris, France, 1996; pp. 445–473. [Google Scholar]

- HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé). Comment Repérer la Fragilité en Soins Ambulatoires—Note Méthodologique et Synthèse Documentaire. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-06/annexe_methodologique__fragilite__vf.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Available online: https://www.sfmu.org/upload/consensus/pa_urgs_court.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Stadnyk, K.; MacKnight, C.; McDowell, I.; Hébert, R.; Hogan, D.B. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet 1999, 353, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.O.; Dramé, M.; Jolly, D.; Novella, J.L.; Blanchard, F.; Michel, J.P. Que nous apprend la cohorte SAFEs sur l’adaptation des filières de soins intra-hospitalières à la prise en charge des patients âgés? Presse Med. 2010, 39, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dramé, M.; Dia, P.A.J.; Jolly, D.; Lang, P.O.; Mahmoudi, R.; Schwebel, G.; Kack, M.; Debart, A.; Courtaigne, B.; Lanièce, I.; et al. Facteurs prédictifs de mortalité à long terme chez des patients âgés de 75 ans ou plus hospitalisés en urgence: La cohorte SAFES. J. Eur. Urgences 2010, 23, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanpain, N.; Chardon, O. Projections de Population à L’horizon 2060. Insee Première. Enquêtes et Études Démographiques; Insee Première n°1320; L’Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques: Paris, France, 2010.

- Schoevaerdts, D.; Biettlot, S.; Malhomme, B.; Rezette, C.; Gillet, J.B.; Vanpee, D.; Cornette, P.; Swine, C. Identification précoce du profil gériatrique en salle d’urgences: Présentation de la grille SEGA. Rev. Gériatrie 2004, 29, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, C.; Godaert, L.; Dramé, M.; Bujoreanu, P.; Collart, M.; Hurtaud, A.; Novella, J.-L.; Sanchez, S. Predictive capacity of the modified SEGA frailty scale upon discharge from geriatric hospitalisation: A six-month prospective study. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2020, 18, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.; Bellavance, F.; Cardin, S.; Trepanier, S.; Verdon, J.; Ardman, O. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: The ISAR screening tool. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.; Bellavance, F.; Cardin, S.; Belzile, E.; Verdon, J. Prediction of hospital utilization among elderly patients during the 6 months after an emergency department visit. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2000, 36, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.; Cardin, S.; Bellavance, F.; Belzile, É. Return to the emergency department among elders: Patterns and predictors. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2000, 7, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, F.; Morichi, V.; Grilli, A.; Spazzafumo, L.; Giorgi, R.; Polonara, S.; De Tommaso, G.; Dessì-Fulgheri, P. Predictive validity of the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) screening tool in elderly patients presenting to two Italian Emergency Departments. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 21, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, F.; Morichi, V.; Grilli, A.; Lancioni, L.; Spazzafumo, L.; Polonara, S.; Abbatecola, A.M. Screening for frailty in elderly emergency department patients by using the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.L.; Fang, J.; Lou, Q.Q.; Anderson, R.M. A systematic review of the identification of seniors at risk (ISAR) tool for the prediction of adverse outcome in elderly patients seen in the emergency department. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 4778–4786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Caoimh, R.; Costello, M.; Small, C.; Spooner, L.; Flannery, A.; O’Reilly, L.; Heffernan, L.; Mannion, E.; Maughan, A.; Joyce, A.; et al. Comparison of Frailty Screening Instruments in the Emergency Department. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slankamenac, K.; Haberkorn, G.; Meyer, O.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Keller, D.I. Prediction of Emergency Department Re-Visits in Older Patients by the Identification of Senior at Risk (ISAR) Screening. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, C.E.; Giannelli, S.V.; Herrmann, F.; Sarasin, F.; Michel, J.-P.; Zekry, D.S.; Chevalley, T. Identification of older patients at risk of unplanned readmission after discharge from the emergency department—Comparison of two screening tools. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 141, w13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahy, A.; Corey, G.; Purtill, H.; O’Neill, A.; Devlin, C.; Barry, L.; Cummins, N.; Gabr, A.; Mohamed, A. Screening instruments to predict adverse outcomes for undifferentiated older adults attending the Emergency Department: Results of SOAED prospective cohort study. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total N = 255 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 82.1 ± 8.2 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 145/255 (56.9) |

| Male | 110/255 (43.1) |

| Method of referral to emergency department | |

| Patient | 61/254 (24.0) |

| Attending physician | 54/254 (21.3) |

| Emergency call center | 134/254 (52.8) |

| Other | 5/254 (2.0) |

| Chaumont Hospital Emergency Dept. | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Nursing home | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Doctor on call | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Out-patient care nurse | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Reason for admission to the emergency room | |

| Fall | 51/254 (20.0) |

| Altered general condition | 28/255 (11.0) |

| Digestive (excluding digestive bleeding) | 30/255 (11.8) |

| Digestive bleeding | 3/255 (1.2) |

| Chest pain | 16/255 (6.3) |

| Dyspnea | 26/255 (10.2) |

| Malaise | 18/255 (7.1) |

| Neurological | 14/255 (5.5) |

| External bleeding | 8/255 (3.1) |

| Other | 61/255 (23.9) |

| mSEGA 1 frailty scale | |

| Low-frailty patients | 78/255 (30.6) |

| Frail patients | 49/255 (19.2) |

| Very frail patients | 128/255 (50.2) |

| Charlson score, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 2.0 |

| Medication, median (EIQ) | 8 (5–10) |

| Polypharmacy 2 | 182/253 (71.9) |

| Institutional living | 44/255 (17.2) |

| Home care | 90/255 (35.3) |

| Orientation after admission | |

| Returned home | 103/255 (40.4) |

| Hospitalization | 152/255 (59.6) |

| Total N = 255 | Frail/Very Frail Patients N = 177 | Low-Frailty Patients N = 78 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutionalization within 12 months 1 | 11/210 (5.2) | 10/132 (7.6) | 1/78 (1.3) | 0.06 |

| Home care initiated within 12 months 2 | 19/120 (15.8) | 9/48 (18.7) | 10/72 (13.9) | 0.47 |

| Deaths 3 | 63/255 (24.7) | 53/177 (29.9) | 10/78 (12.8) | 0.004 |

| Emergency readmission | 30/62 (48.4) | 26/52 (50.0) | 4/10 (40.0) | 0.61 |

| Without emergency readmission | 32/62 (51.6) | 26/52 (50.0) | 6/10 (60.0) | |

| Possible readmission to emergency department during 12 months | 71/254 (27.9) | 59/176 (33.5) | 12/78 (15.4) | 0.003 |

| Institutionalization N = 11 | Not Institutionalized N = 199 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty | 0.06 | ||

| Low-frailty patients | 1/11 (9.1) | 77/199 (38.7) | |

| Frail/very frail patients | 10/11 (90.9) | 122/199 (61.3) | |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 83.3 ± 6.5 | 80.5 ± 7.9 | 0.25 |

| Sex | 0.84 | ||

| Female | 6/11 (54.5) | 102/198 (51.5) | |

| Male | 5/11 (45.5) | 96/198 (48.5) | |

| Charlson score, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 0.84 |

| Polypharmacy | 8/11 (72.7) | 138/197 (94.7) | 1.00 |

| Home Care Provided N = 19 | Home Care Not Provided N = 101 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty | 0.47 | ||

| Low-frailty patients | 10/19 (52.6) | 62/101 (61.4) | |

| Frail/very frail patients | 9/19 (47.4) | 39/101 (38.6) | |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 80.6 ± 6.4 | 78.0 ± 7.7 | 0.17 |

| Sex | 0.98 | ||

| Female | 9/19 (47.4) | 47/100 (47.0) | |

| Male | 10/19 (52.6) | 53/100 (53.0) | |

| Charlson score, mean ± SD | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 0.52 |

| Polypharmacy | 11/19 (61.1) | 62/101 (61.4) | 0.98 |

| Readmission N = 71 | Not Readmitted N = 183 | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Adjusted OR 1(CI 95%) | p-Value | |||

| Frailty | 0.003 | 0.005 | |||

| Low-frailty patients | 12 (16.9) | 66 (36.1) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Frail/very frail patients | 59 (83.1) | 117 (63.9) | 2.71 (1.36–5.41) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 82.4 ± 8.5 | 81.9 ± 8.1 | 0.69 | - | - |

| Sex | 0.81 | - | |||

| Female | 39 (55.7) | 105 (57.4) | - | ||

| Male | 31 (44.3) | 78 (42.6) | - | ||

| Charlson score, mean ± SD | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 0.07 | - | - |

| Polypharmacy | 56 (80.0) | 125 (68.7) | 0.07 | - | - |

| Deaths | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) 1 | HR (CI 95%) | p-Value | Adjusted HR 2 (CI 95%) | p-Value | |

| Frailty | 0.006 | - | |||

| Low-frailty patients | 10 (12.8) | 1.00 (ref) | - | ||

| Frail/very frail patients | 53 (29.9) | 2.60 (1.32–5.10) | - | ||

| Age | - | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.02 | - | - |

| Sex | 0.33 | - | |||

| Female | 31 (28.4) | 1.00 (ref) | - | ||

| Male | 32 (22.1) | 0.78 (0.48–1.28) | - | ||

| Charlson score | - | 1.25 (1.13–1.39) | <0.0001 | 1.26 (1.14–1.39) | <0.0001 |

| Polypharmacy | 0.03 | - | |||

| No | 11 (15.5) | 1.00 (ref) | - | ||

| Yes | 52 (28.6) | 2.02 (1.06–3.88) | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zulfiqar, A.-A.; Fresne, M.; Andres, E. Assessing the Efficacy of the Modified SEGA Frailty (mSEGA) Screening Tool in Predicting 12-Month Morbidity and Mortality among Elderly Emergency Department Visitors. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226972

Zulfiqar A-A, Fresne M, Andres E. Assessing the Efficacy of the Modified SEGA Frailty (mSEGA) Screening Tool in Predicting 12-Month Morbidity and Mortality among Elderly Emergency Department Visitors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(22):6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226972

Chicago/Turabian StyleZulfiqar, Abrar-Ahmad, Mathieu Fresne, and Emmanuel Andres. 2023. "Assessing the Efficacy of the Modified SEGA Frailty (mSEGA) Screening Tool in Predicting 12-Month Morbidity and Mortality among Elderly Emergency Department Visitors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 22: 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226972

APA StyleZulfiqar, A.-A., Fresne, M., & Andres, E. (2023). Assessing the Efficacy of the Modified SEGA Frailty (mSEGA) Screening Tool in Predicting 12-Month Morbidity and Mortality among Elderly Emergency Department Visitors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(22), 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12226972