EYERUBBICS: The Eye Rubbing Cycle Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

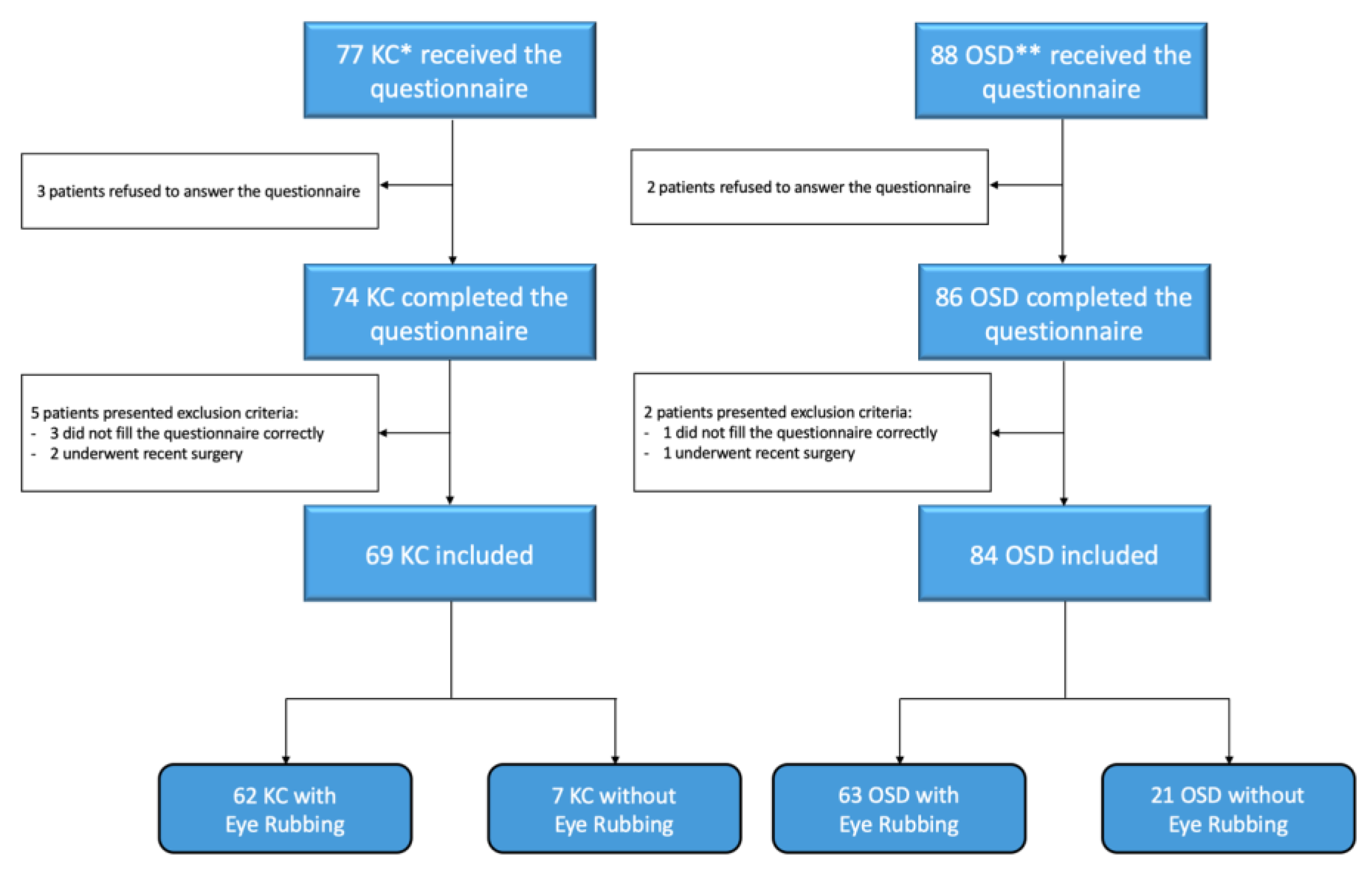

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Comparison of Keratoconus (KC) and Ocular Surface Disease (OSD) Groups

3.3. Comparison of Rubbing (R) and Non-Rubbing (NR) Groups

3.4. Eye Rubbing Analysis

3.5. Comparison According to Goodman Criteria

3.6. Intention to Stop after the Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cevikbas, F.; Lerner, E.A. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Itch. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 945–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, M.M.; Nguyen, A.L.; Bielory, L. Allergic Conjunctivitis and Dry Eye Syndrome. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012, 108, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, C.; Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Shafer, B.M.; Shevchenko, A.; Nattkemper, L.A.; Chan, Y.-H.; Tabaac, S.; Schardt, M.J.; Najjar, D.M.; Foster, W.J.; et al. The Prevalence and Characteristics of Chronic Ocular Itch: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Itch 2017, 2, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoma, A.; Steinhoff, M.; Ständer, S.; Yosipovitch, G.; Schmelz, M. The Neurobiology of Itch. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, E.; Nanavaty, M. Eye Rubbing and Keratoconus: A Literature Review. Int. J. Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2015, 3, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, H.; Mobarki, Y.; Mania, K.; Altowairqi, B.; Basehi, M.; Mahfouz, M.S.; Elmahdy, M. The Correlation between Keratoconus and Eye Rubbing: A Review. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 12, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes-Rodriguez, R.; Rowe, B.; Lee, H.G.; Moldovan, T.; Chan, Y.-H.; Blum, M.; Yosipovitch, G. Chronic Pruritus in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Characteristics and Effect on Quality of Life. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, J.V.; Peace, D.G.; Baird, R.S.; Allansmith, M.R. Effects of Eye Rubbing on the Conjunctiva as a Model of Ocular Inflammation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1985, 100, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatinel, D. Challenging the “No Rub, No Cone” Keratoconus Conjecture. Int. J. Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2018, 7, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, J.V.; Leahy, C.D.; Welter, D.A.; Hearn, S.L.; Weidman, T.A.; Korb, D.R. Histopathology of the Ocular Surface after Eye Rubbing. Cornea 1997, 16, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Yang, W.; Guo, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, F.; Xiao, M.; Davidson, S.; Yu, G.; Duan, B.; Huang, T.; et al. Anatomical and Functional Dichotomy of Ocular Itch and Pain. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, G. The Itch-Scratch Cycle: A Review of the Mechanisms. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2019, 9, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiuji, Y. Addiction and the Itch-Scratch Cycle. What Do They Have in Common? Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, H.; Papoiu, A.D.P.; Nattkemper, L.A.; Lin, A.C.; Kraft, R.A.; Coghill, R.C.; Yosipovitch, G. Scratching Induces Overactivity in Motor-Related Regions and Reward System in Chronic Itch Patients. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2814–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Arita, R.; Chalmers, R.; Djalilian, A.; Dogru, M.; Dumbleton, K.; Gupta, P.K.; Karpecki, P.; Lazreg, S.; Pult, H.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A. Addiction: Definition and Implications. Br. J. Addict. 1990, 85, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.A. Detecting Alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA 1984, 252, 1905–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudouin, C.; Messmer, E.M.; Aragona, P.; Geerling, G.; Akova, Y.A.; Benítez-del-Castillo, J.; Boboridis, K.G.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Rolando, M.; Labetoulle, M. Revisiting the Vicious Circle of Dry Eye Disease: A Focus on the Pathophysiology of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, H.; Kakigi, R. Itch and Brain. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Kim, Y.S.; Olson, W.P.; Li, F.; Guo, C.; Luo, W.; Huang, A.J.W.; Liu, Q. A Histamine-Independent Itch Pathway Is Required for Allergic Ocular Itch. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1267–1270.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.N. Expanding Our Understanding of Eye Rubbing and Keratoconus. Cornea 2010, 29, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crummy, E.A.; O’Neal, T.J.; Baskin, B.M.; Ferguson, S.M. One Is Not Enough: Understanding and Modeling Polysubstance Use. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A.; Marian, M.; Drăgoi, A.M.; Costea, R.-V. Understanding the Genetics and Neurobiological Pathways behind Addiction (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, S.; Scholes, S.; Shelton, N.; Connor, J. Assessment of Non-Response Bias in Estimates of Alcohol Consumption: Applying the Continuum of Resistance Model in a General Population Survey in England. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T.; Macdonald, S. Non-Response Bias in Alcohol and Drug Population Surveys. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2009, 28, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Chamberlain, S.R. Expanding the Definition of Addiction: DSM-5 vs. ICD-11. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMonnies, C.W. Behaviour Modification in the Management of Chronic Habits of Abnormal Eye Rubbing. Contactlens Anterior Eye 2009, 32, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Population (n = 153) | Keratoconus (n = 69) | Ocular Surface Disease (n = 84) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.8 ± 17 | 30.1 ± 9 | 45.9 ± 18 | ≤0.001 |

| Sex | 94 F (61.4%) | 37 F (53.6%) | 57 F (67.9%) | 0.07 |

| Nighttime work | 11 (7.2%) | 8 (11.6%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0.06 |

| Keratoconus | 69 (45.1%) | 69 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ≤0.0001 |

| Dry eye disease | 81 (52.9%) | 4 (5.8%) | 77 (91.7%) | ≤0.0001 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 16 (10.5%) | 2 (2.9%) | 14 (16.7%) | 0.006 |

| Blepharitis | 20 (13.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | 19 (22.6%) | <0.0001 |

| History of eye surgery | 34 (22.2%) | 19 (27.5%) | 15 (17.9%) | 0.15 |

| Cataract surgery | 11 (7.2%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (13.1%) | 0.002 |

| Corneal graft | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0.22 |

| Crosslinking | 12 (7.8%) | 12 (17.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 |

| Glasses | 112 (73.2%) | 50 (72.5%) | 62 (73.8%) | 0.86 |

| Soft lenses | 11 (7.2%) | 1 (1.5%) | 10 (11.9%) | 0.01 |

| Rigid lenses | 19 (12.4%) | 16 (23.2%) | 3 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmologic treatment | 96 (62.7%) | 39 (56.5%) | 57 (67.9%) | 0.15 |

| Artificial tears | 86 (56.2%) | 32 (46.4%) | 54 (63.3%) | 0.03 |

| Antiallergic drops | 35 (22.9%) | 23 (33.3%) | 12 (14.3%) | 0.005 |

| Anti-inflammatory drops | 29 (19%) | 4 (5.8%) | 25 (29.8%) | <0.001 |

| Dermatological history | 44 (28.8%) | 12 (17.4%) | 32 (38.1%) | 0.005 |

| Allergy | 72 (47.1%) | 32 (44.4%) | 40 (47.6%) | 0.88 |

| Skin pruritus | 53 (34.6%) | 18 (26.1%) | 35 (41.7%) | 0.04 |

| Skin scratch | 45 (29.4%) | 13 (18.8%) | 32 (38.1%) | 0.009 |

| Active smoking | 27 (17.6%) | 10 (14.5%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.36 |

| Addictive history | 18 (11.8%) | 5 (7.2%) | 13 (15.5%) | 0.12 |

| Alcohol | 5 (3.3%) | 2 (2.9%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0.82 |

| Tobacco | 11 (7.2%) | 1 (1.4%) | 10 (11.9%) | 0.01 |

| Video games | 3 (2%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.054 |

| Psychiatric history | 38 (24.8%) | 13 (18.8%) | 25 (29.8%) | 0.12 |

| Depression | 21 (13.7%) | 9 (13%) | 12 (14.3%) | 0.82 |

| Anxiety | 29 (19%) | 9 (13%) | 20 (23.8%) | 0.09 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (2.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | 3 (3.6%) | 0.41 |

| Psychiatric follow-up | 6 (3.9%) | 2 (2.9%) | 4 (4.8%) | 0.56 |

| Familial psychiatric history | 21 (13.7%) | 4 (5.8%) | 17 (20.2%) | 0.01 |

| Ocular symptoms | 137 (89.5%) | 58 (84.1%) | 79 (94%) | 0.045 |

| Ocular pruritus | 74 (48.8%) | 40 (58%) | 34 (40.5%) | 0.03 |

| Ocular burning | 42 (27.5%) | 6 (8.7%) | 36 (42.9%) | ≤0.0001 |

| Dryness | 36 (23.5%) | 8 (11.6%) | 28 (33.3%) | 0.002 |

| Foreign body sensation | 24 (15.7%) | 10 (14.5%) | 14 (16.7%) | 0.71 |

| Irritation | 39 (25.5%) | 16 (23.2%) | 23 (27.4%) | 0.56 |

| Discomfort | 22 (14.4%) | 11 (15.9%) | 11 (13.1%) | 0.62 |

| SANDE score for symptoms | ||||

| Frequency (/100) | 55.07 | 44.37 | 63.48 | ≤0.001 |

| Intensity (/100) | 51.96 | 42.5 | 58.9 | ≤0.001 |

| Eye rubbing | 125 (81.7%) | 62 (89.9%) | 63 (75%) | 0.02 |

| CDVA * (LogMAR) | 0,06 | 0.1 | 0.02 | ≤0.001 |

| Papillae | 88 (57.5%) | 50 (72.5%) | 38 (45.2%) | < 0.001 |

| MGD ** | 54 (35.3%) | 5 (7.2%) | 49 (58.3%) | ≤0.0001 |

| Mean BUT *** | 6.35 | 6.88 | 5.9 | 0.03 |

| Mean Oxford grade | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.81 | ≤0.001 |

| Study Population (n = 153) | No Rubbing (n = 28) | Rubbing (n = 125) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.8 | 45.9 | 37.2 | 0.02 |

| Sex | 94 F (61.4%) | 16 F (57.1%) | 78 F (62.4%) | 0.60 |

| Nighttime work | 11 (7.2%) | 2 (7.1%) | 9 (7.2%) | 0.99 |

| Keratoconus | 69 (45.1%) | 7 (25%) | 62 (49.6%) | 0.02 |

| Dry eye disease | 81 (52.9%) | 20 (71.4%) | 61 (48.8%) | 0.03 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 16 (10.5%) | 1 (3.6%) | 15 (12%) | 0.19 |

| Blepharitis | 20 (13.1%) | 4 (14.3%) | 16 (12.8%) | 0.83 |

| History of eye surgery | 34 (22.2%) | 7 (25%) | 27 (21.6%) | 0.69 |

| Cataract surgery | 11 (7.2%) | 4 (14.3%) | 7 (5.6%) | 0.11 |

| Corneal graft | 4 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.34 |

| Crosslinking | 12 (7.8%) | 1 (3.6%) | 11 (8.8%) | 0.35 |

| Glasses | 112 (73.2%) | 21 (75%) | 91 (72.8%) | 0.81 |

| Soft lenses | 11 (7.2%) | 3 (10.7%) | 8 (6.4%) | 0.43 |

| Rigid lenses | 19 (12.4%) | 1 (3.6%) | 18 (14.4%) | 0.12 |

| Ophthalmologic treatment | 96 (62.7%) | 18 (64.3%) | 78 (62.4%) | 0.86 |

| Artificial tears | 86 (56.2%) | 16 (57.1%) | 70 (56%) | 0.91 |

| Antiallergic drops | 35 (22.9%) | 3 (10.7%) | 32 (25.6%) | 0.09 |

| Anti-inflammatory drops | 29 (19%) | 9 (32.1%) | 20 (16%) | 0.049 |

| Dermatological history | 44 (28.8%) | 10 (35.7%) | 34 (27.2%) | 0.37 |

| Allergy | 72 (47.1%) | 7 (25%) | 65 (52%) | 0.009 |

| Skin pruritus | 53 (34.6%) | 5 (17.9%) | 48 (38.4%) | 0.04 |

| Skin scratch | 45 (29.4%) | 4 (14.3%) | 41 (32.8%) | 0.053 |

| Active smoking | 27 (17.6%) | 5 (17.9%) | 22 (17.6%) | 0.97 |

| Addictive history | 18 (11.8%) | 3 (10.7%) | 15 (12%) | 0.85 |

| Psychiatric history | 38 (24.8%) | 7 (25%) | 31 (24.8%) | 0.98 |

| Depression | 21 (13.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 16 (12.8%) | 0.48 |

| Anxiety | 29 (19%) | 5 (17.9%) | 24 (19.2%) | 0.87 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (2.6%) | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.097 |

| Psychiatric follow-up | 6 (3.9%) | 2 (7.1%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.33 |

| Familial psychiatric history | 21 (13.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 16 (12.8%) | 0.48 |

| Ocular symptoms | 137 (89.5%) | 21 (75%) | 116 (92.8%) | 0.0056 |

| Ocular pruritus | 74 (48.8%) | 2 (7.1%) | 72 (57.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Ocular burning | 42 (27.5%) | 11 (39.3%) | 31 (24,8%) | 0.12 |

| Dryness | 36 (23.5%) | 8 (28.6%) | 28 (22.4%) | 0.49 |

| Foreign body sensation | 24 (15.7%) | 3 (10.7%) | 21 (16.8%) | 0.43 |

| Irritation | 39 (25.5%) | 7 (25%) | 32 (25.6%) | 0.95 |

| Discomfort | 22 (14.4%) | 2 (7.1%) | 20 (16%) | 0.23 |

| SANDE score for symptoms | ||||

| Frequency (/100) | 55.07 | 59.24 | 54.78 | 0.50 |

| Intensity (/100) | 51.96 | 59.95 | 51.05 | 0.36 |

| CDVA * (LogMAR) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.34 |

| Papillae | 88 (57.5%) | 6 (21.4%) | 82 (65.6%) | <0.0001 |

| MGD ** | 54 (35.3%) | 17 (60.7%) | 37 (29.6%) | 0.0019 |

| Mean BUT *** | 6.35 | 7.27 | 6.14 | 0.047 |

| Mean Oxford grade | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.01 |

| Rubbing (n = 125) | Keratoconus (n = 62) | Ocular Surface Disease (n = 63) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye rubbing characteristics | ||||

| Occasional | 63 (50.4%) | 37 (59.7%) | 26 (41.3%) | 0.04 |

| Daily | 55 (44%) | 20 (32.3%) | 35 (55.6%) | 0.009 |

| Daily frequency (/100) | 42.5 | 35.66 | 49.22 | 0.002 |

| Duration (/100) | 37.36 | 35.58 | 39.11 | 0.46 |

| More frequent during morning | 11 (8.8%) | 8 (12.9%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0.11 |

| More frequent at night | 51 (40.8%) | 33 (53.2%) | 51 (28.6%) | 0.005 |

| No preference for period of day | 70 (56%) | 25 (40.3%) | 45 (71.4%) | ≤0.001 |

| Goodman criteria | ||||

| Goodman criteria score (/16) | 5.82 | 5.58 | 6.06 | 0.38 |

| Goodman ≥ 5 | 79 (63.2%) | 39 (62.9%) | 40 (63.5%) | 0.95 |

| CAGE score | ||||

| Mean CAGE | 2.23 | 2.34 | 2.13 | 0.33 |

| CAGE ≥ à 2 | 93 (74.4%) | 49 (79%) | 44 (69.8%) | 0.24 |

| Intention to stop | 87 (69.6%) | 53 (60.9%) | 34 (39.1%) | ≤0.0001 |

| Rubbing (n = 125) | Goodman Score < 5 (n = 46) | Goodman Score ≥ 5 (n = 79) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.2 | 35.9 | 38 | 0.48 |

| Sex | 78 F (62.4%) | 24 F (52.2%) | 54 F (68.4%) | 0.07 |

| Keratoconus | 62 (49.6%) | 23 (50%) | 39 (49.4%) | 0.95 |

| Dry eye disease | 61 (48.8%) | 22 (47.8%) | 39 (49.4%) | 0.87 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 15 (12%) | 6 (40%) | 9 (11.4%) | 0.07 |

| Blepharitis | 16 (12.8%) | 7 (15.2%) | 9 (11.4%) | 0.54 |

| History of eye surgery | 27 (21.6%) | 9 (19.6%) | 18 (22.8%) | 0.67 |

| Glasses | 91 (72.8%) | 32 (69.6%) | 59 (74.7%) | 0.54 |

| Soft lenses | 8 (6.4%) | 5 (11.1%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.11 |

| Rigid lenses | 18 (14.4%) | 8 (17.4%) | 10 (12.7%) | 0.47 |

| Ophthalmologic treatment | 78 (62.4%) | 30 (65.2%) | 48 (60.8%) | 0.62 |

| Artificial tears | 70 (56%) | 28 (60.9%) | 42 (53.2%) | 0.40 |

| Antiallergic drops | 32 (25.6%) | 10 (21.7%) | 22 (27.8%) | 0.45 |

| Anti-inflammatory drops | 20 (16%) | 9 (19.6%) | 11 (13.9%) | 0.41 |

| Dermatological history | 34 (27.2%) | 8 (17.4%) | 26 (32.9%) | 0.06 |

| Allergy | 65 (52%) | 23 (50%) | 42 (53.2%) | 0.73 |

| Skin pruritus | 48 (38.4%) | 13 (28.3%) | 35 (44.3%) | 0.08 |

| Skin scratch | 41 (32.8%) | 12 (26.1%) | 29 (36.7%) | 0.22 |

| Active smoking | 22 (17.6%) | 5 (10.9%) | 17 (21.5%) | 0.13 |

| Addictive history | 15 (12%) | 2 (4.3%) | 13 (16.5%) | 0.045 |

| Psychiatric history | 31 (24.8%) | 8 (17.4%) | 23 (29.1%) | 0.15 |

| Depression | 16 (12.8%) | 3 (6.5%) | 13 (16.5%) | 0.11 |

| Anxiety | 24 (19.2%) | 7 (15.2%) | 17 (21.5%) | 0.39 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0.28 |

| Psychiatric follow-up | 4 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (5.1%) | 0.12 |

| Familial psychiatric history | 16 (12.8%) | 2 (4.3%) | 14 (17.7%) | 0.03 |

| Ocular symptoms | 116 (92.8%) | 39 (84.8%) | 77 (97.5%) | 0.008 |

| Ocular pruritus | 72 (57.6%) | 18 (39.1%) | 54 (68.4) | 0.002 |

| Ocular burning | 31 (24.8%) | 10 (21.7%) | 21 (26.6%) | 0.55 |

| Dryness | 28 (22.4%) | 10 (21.7%) | 18 (22.8%) | 0.89 |

| Foreign body sensation | 21 (16.8%) | 11 (23.9%) | 10 (12.7%) | 0.11 |

| Irritation | 32 (25.6%) | 8 (17.4%) | 24 (30.4%) | 0.11 |

| Discomfort | 20 (16%) | 8 (17.4%) | 12 (15.2%) | 0.75 |

| SANDE score for symptoms | ||||

| Frequency (/100) | 54.78 | 46.74 | 58.91 | 0.03 |

| Intensity (/100) | 51.05 | 39.21 | 57.05 | 0.001 |

| CDVA * (LogMAR) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Papillae | 79 (63.2%) | 21 (48.8%) | 58 (70.7%) | 0.02 |

| MGD ** | 37 (29.6%) | 16 (34.8%) | 21 (26.6%) | 0.33 |

| Mean BUT *** | 6.14 | 6.8 | 5.75 | 0.03 |

| Mean Oxford grade | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.33 |

| Eye rubbing characteristics | ||||

| Frequency per day (/100) | 42.5 | 29.7 | 49.9 | ≤0.001 |

| Duration (/100) | 37.36 | 24.37 | 44.92 | ≤0.001 |

| More frequent during morning | 11 (8.8%) | 4 (8.7%) | 7 (8.9%) | 0.98 |

| More frequent at night | 51 (40.8%) | 19 (41.3%) | 32 (40.5%) | 0.93 |

| No preference for period of day | 70 (56%) | 25 (54.3%) | 45 (57%) | 0.78 |

| Intention to stop | 87 (69.6%) | 32 (69.6%) | 55 (69.6%) | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hage, A.; Knoeri, J.; Leveziel, L.; Majoulet, A.; Blanc, J.-V.; Buffault, J.; Labbé, A.; Baudouin, C. EYERUBBICS: The Eye Rubbing Cycle Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041529

Hage A, Knoeri J, Leveziel L, Majoulet A, Blanc J-V, Buffault J, Labbé A, Baudouin C. EYERUBBICS: The Eye Rubbing Cycle Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041529

Chicago/Turabian StyleHage, Alexandre, Juliette Knoeri, Loïc Leveziel, Alexandre Majoulet, Jean-Victor Blanc, Juliette Buffault, Antoine Labbé, and Christophe Baudouin. 2023. "EYERUBBICS: The Eye Rubbing Cycle Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041529

APA StyleHage, A., Knoeri, J., Leveziel, L., Majoulet, A., Blanc, J.-V., Buffault, J., Labbé, A., & Baudouin, C. (2023). EYERUBBICS: The Eye Rubbing Cycle Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041529