Abstract

Background/Objectives: Although SARS-CoV-2 infection is a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE), data on the impact of the use of non-invasive ventilation support (NIVS) to mitigate the risk of VTE during hospitalization are scarce. Methods: Data for 1471 SARS-CoV-2 patients, hospitalized in a single hub during the first pandemic wave, were collected from clinical records, including symptom duration and type, information on lung abnormalities on chest computed tomography (CT), laboratory parameters and the use of NIVS. Determining VTE occurrence during hospital stays was the main endpoint. Results: Patients with VTE (1.8%) had an increased prevalence of obesity (26% vs. 11%), diabetes (41% vs. 21%), higher CHA2DS2VASC score (4, IQR 2–5 vs. 3, IQR 1–4, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.021) and cough (65% vs. 44%) and experienced significantly higher rates of NIVS (44% vs. 8%). Using a stepwise multivariate logistic regression model, the prevalence of electrocardiogram abnormalities (odds ratio (OR) 2.722, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.039–7.133, p = 0.042), cough (OR 3.019, 95% CI 1.265–7.202, p = 0.013), CHA2DS2-VASC score > 3 (OR 3.404, 95% CI 1.362–8.513, p = 0.009) and the use of NIVS (OR 15.530, 95% CI 6.244–38.627, p < 0.001) were independently associated with a risk of VTE during hospitalization. NIVS remained an independent risk factor for VTE even after adjustment for the period of admission within the pandemic wave. Conclusions: Our study suggests that NIVS is a risk factor for VTE during hospitalization in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Future studies should assess the optimal prophylactic strategy against VTE in patients with a SARS-CoV-2 infection candidate to non-invasive ventilatory support.

1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a worldwide health problem. The annual incidence of VTE in the general population is estimated to be around 1–2 cases per 1000 persons [1,2]. It is estimated that PE, the most feared presentation of VTE, causes 6–12 deaths per 100,000 people, corresponding to around 40,000 deaths per year in the European Region [3,4]. Hospitalized patients with acute medical illness are at high risk of VTE during hospitalization. Several hospitalization-specific factors (such as immobilization, sedation, vasopressors or central venous catheters) together with individual patient-related factors (such as age, cancer, obesity, immobilization, history of personal or familiarities for VTE, sepsis, respiratory or heart failure, pregnancy, stroke, trauma or recent surgery) together contribute to this risk [5,6]. Thus, all hospitalized patients are assessed for VTE risk and are often administered thromboprophylaxis. SARS-CoV-2 is a viral respiratory tract infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection that led to a pandemic in early 2020 in Western countries after spreading from China. SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to endothelial damage, with vascular thrombosis and micro-angiopathy, and occlusion of alveolar capillaries with a significant intussusceptive angiogenesis and new vessel [7]. There are several biomarkers associated with the severity of COVID-19, including C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer levels and troponin [8]. COVID-19 patients who die exhibit higher levels of troponin I, D-dimer and CRP when compared with COVID-19 survivors [9]. Thus, prognostic levels of biomarkers associated with COVID-19 may assist in understanding the progression of the disease. Severe SARS-CoV-2 is often complicated with coagulopathy, with related prothrombotic effects and a high risk of VTE [5,10,11]. International societies strongly recommend the use of thromboprophylaxis in all hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [12,13,14,15]. Despite thromboprophylaxis administration, hospitalization of SARS-CoV-2 patients is frequently complicated by VTE. While the incidence of thrombotic complications in critical SARS-CoV-2 patients is very high, as the incidence in patients under non-invasive respiratory ventilation support (NIVS) is still unknown [16,17]. The specific incidence of thrombotic events in each of the clinical scenarios within the broad spectrum of severity of SARS-CoV-2 is not clearly established and this has not allowed the implementation of thromboprophylaxis or anticoagulation for routine care in SARS-CoV-2 patients [18,19]. In this context, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the incidence of VTE in patients hospitalized for suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first pandemic wave, especially in relation to the administration of NIVS for respiratory failure during hospitalization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics and Data Collection

This study was conducted in an Internal Medicine Unit of a large teaching hospital in Northern Italy (Parma University-Hospital), which was appointed as the main hub for the care of SARS-CoV-2 patients for the whole Parma province (approximately 450,000 inhabitants) in the earliest phases of the first wave [20]. Two groups of patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 from 28 February 2020 to 10 June 2020 were retrospectively enrolled after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria. We arbitrarily divided this time frame, corresponding to the first pandemic wave, into two periods named “first period” from 28 February 2020 to 22 March 2020, and “second period” from 22 March 2020 to 10 June 2020. These subclassifications were made to distinguish the first period characterized by a high rate of hospitalization/per day and exceptional burden for the whole healthcare system from the second period (corresponding to the descending phase of the same pandemic wave) characterized by a lower rate of hospitalization/per day.

Only patients aged ≥18 years old with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by reverse transcriptase polymerase-chain reaction (RT-PCR) by nasopharyngeal swab performed upon urgent admission, or with chest computed tomography (CT) evidence of lung interstitial involvement with a high radiological and clinical suspicion of COVID-19 were included in the study. Thus, subjects with positive chest CTs, but negative RT-PCR tests collected via nasopharyngeal swabs performed upon hospital admission were included in the study and labelled “suspect COVID-19 cases”. In the earliest phases of the pandemic, the epidemiological context was characterized by a high daily number of hospital admissions for respiratory failure (up to 70 admissions per day), so the presence of a chest CT showing interstitial abnormalities allowed doctors to reasonably assume that patients had COVID-19 even if the first RT-PCR test was negative. Conversely, all subjects with missing data on variables needed for the study and subjects who were transferred to other wards (i.e., with missing data on the outcome) were excluded.

For each participant we collect the number and types of comorbidities (including dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, heart diseases and chronic kidney disease), demographic data (sex and age), number of drugs prescribed, clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 (i.e., chest CT abnormalities, symptoms and their duration and vital signs) and the results of lab tests performed on admission, including blood cell count, arterial blood gas analysis, serum creatinine, predicted glomerular filtration rate, D-dimer, CRP and procalcitonin (PCT). We analyzed the following parameters: arterial blood gas analysis (RADIOMETER ABL instrument); blood test: WBC, 1000/mm3 (flow cytometry method, normal values 4.00–10.00); neutrophils, 1000/mm3 (flow cytometry method, normal values 1.80–8.00); lymphocytes, 1000/mm3 (flow cytometry method, normal values 1.00–4.00); creatinine, mg/dL (Jaffè method, normal values 0.5–1.4); C-reactive protein, mg/L (Atellica CH High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, normal values 0.16–10.00); PCT, ng/mL (chemiluminescence immunometric assay, normal values 0.00–0.50); D-dimer, ng/dL (immunological method, normal values < 500); PT and aPTT (coagulation method, normal values INR ratio 0.86–1.20; aPTT ratio 0.82–1.18); fibrinogen, mg/dL (CLAUSS method, 150–400) normal values: pH (7.36–7.44); HCO3−, mmol/L (22–26); pCO2, mmHg (38–42) and pO2, mmHg (85–100). By the use of chest CT visual score, the extension of pulmonary abnormalities and infiltrates was estimated through calculations detailed elsewhere [21]. We also collected data on treatments administered during hospital stay and outcome (survival vs. death) for all participants.

Ethics Committee approval was obtained (Comitato Etico dell’Area Vasta Emilia Nord, Emilia-Romagna region) under the ID 273/2020/OSS/AOUPR as part of a larger project on the characteristics of patients hospitalized with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave. All participants, who were contactable by phone or for follow-up reasons, provided written informed consent for participation. For all other cases, the Ethics Committee, in accordance with the guidelines in force at the moment of approval, waived written informed-consent collection due to the retrospective design of the study.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

Variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) or percentages, as appropriate. The characteristics of participants were compared with the Mann–Whitney or chi-square tests, with adjustment for age and sex with Quade non-parametric ANCOVA (continuous variables) or binary logistic regression (dichotomous variables). The factors independently associated with VTE in both groups were investigated with stepwise multivariate logistic regression models considering the participants altogether and after partition according to pandemic wave. Diabetes, CHA2DS2-VASC SCORE, obesity, admission electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, cough, dyspnea, neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, non-invasive ventilation support and CHA2DS2-VASC SCORE > 3, CHA2DS2-VASC SCORE > 4 were considered entries in these multivariate models. Additional analyses were also made after the categorization of participants of both periods by VTE status.

Analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical package (v. 28, IMB, Armonk, NY, USA), considering p values < 0.05 as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Population

We included in this study 1471 patients admitted from 28 February 2020 to 10 June 2020, of which 27 suffered from VTE and 1444 did not suffer from VTE. Their clinical characteristics are compared in Table 1. Patients without VTE have less comorbidities than those with VTE. The patients with DVT had an increased prevalence of obesity (median 26% vs. 11%), diabetes (41% vs. 21%) and a higher CHA2DS2VASC score than non-DVT SARS-CoV-2 patients (4, IQR 2–5 vs. 3 pt, IQR 1–4, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.021). SARS-CoV-2 patients with DVT took more antiepileptic drugs (19% vs. 7%) and insulin (19% vs. 7%) than non VTE patients. The clinical presentation was also different with the prevalence of a cough (65% vs. 44%) in VTE patients. Patients with DVT had a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities (74% vs. 52%), white-blood-cell count (9.16, IQR 6.62–12.50 vs. 6.99 1000/mm3, IQR 5.12–9.55, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.011), neutrophil count (7.65, IQR 5.43–10.13 vs. 5.32 1000/mm3, IQR 3.62–7.87, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.002) and D-dimer levels (1572, IQR 1003–3859 vs. 1046 ng/dL, IQR 640–2025, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.010). Patients with VTE had the worst O2 saturation during hospitalization (88, IQR 83–91 vs. 92, IQR 88–94, age- and sex-adjusted, p = 0.002) and experienced significantly higher rates of NIVS (44% vs. 8%) and sedative therapy (50% vs. 26%). No statistical differences in mortality rate were found (41% vs. 27%); however, patients with VTE were more often transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) (19% vs. 4%).

Table 1.

Comparison of the main characteristics of COVID-19 presentation and outcomes between patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) (n = 27) and without VTE (n = 1444).

3.2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Model

Using a stepwise multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2), the presence of ECG abnormalities (OR 2.722, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.039–7.133, p = 0.042), cough as symptom of presentation (OR 3.019, 95% CI 1.265–7.202, p = 0.013), neutrophil (OR 1.089, 95% CI 1.015–1.169, p = 0.018), CHA2DS2-VASC score > 3 (OR 3.404, 95% CI 1.362–8.513, p = 0.009) and the use of NISV (OR 15.530, 95%, CI 6.244–38.627, p < 0.001) were independently associated with VTE during hospitalization in SARS-CoV-2 patients.

Table 2.

Factors associated with the risk of VTE using a stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis.

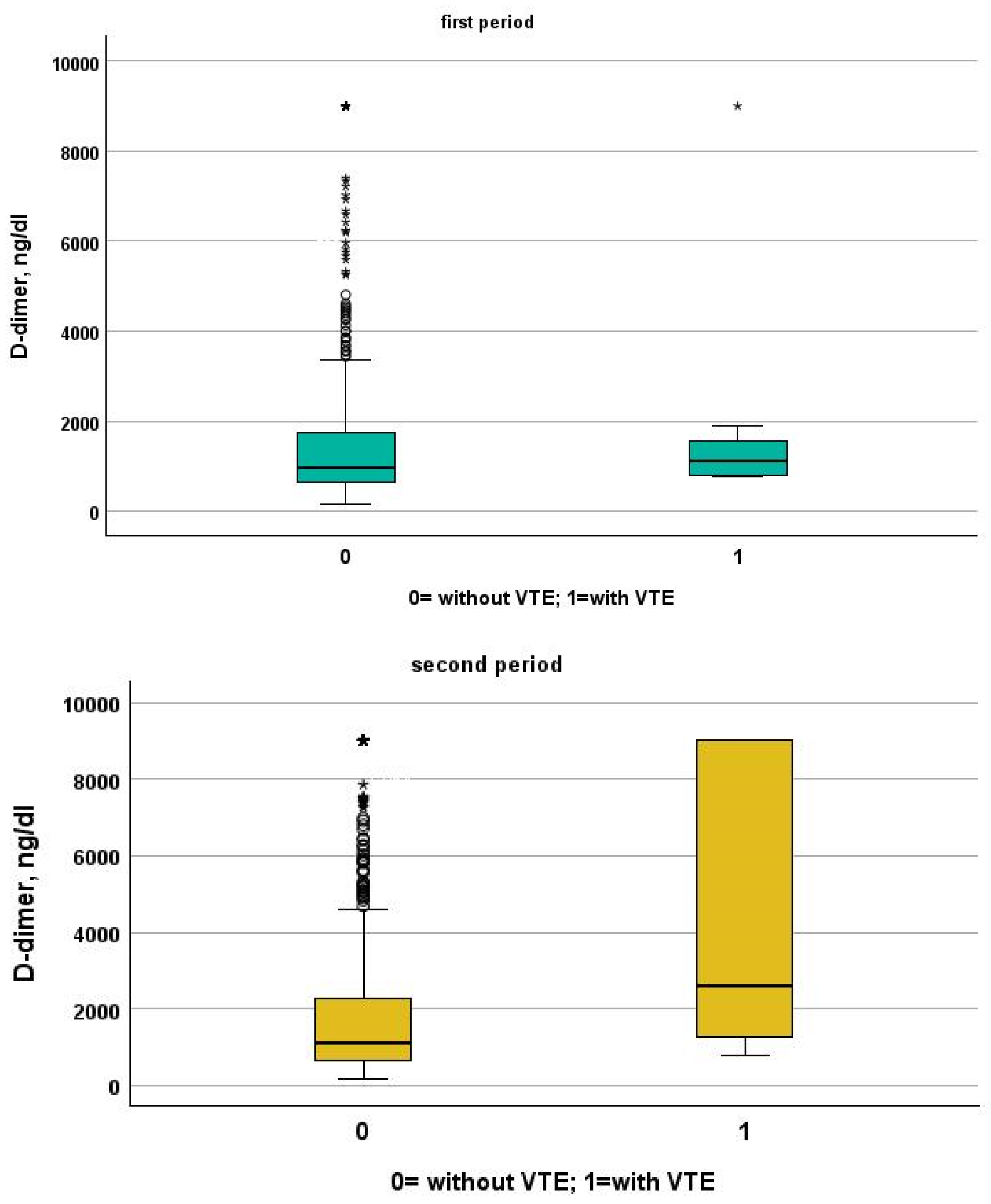

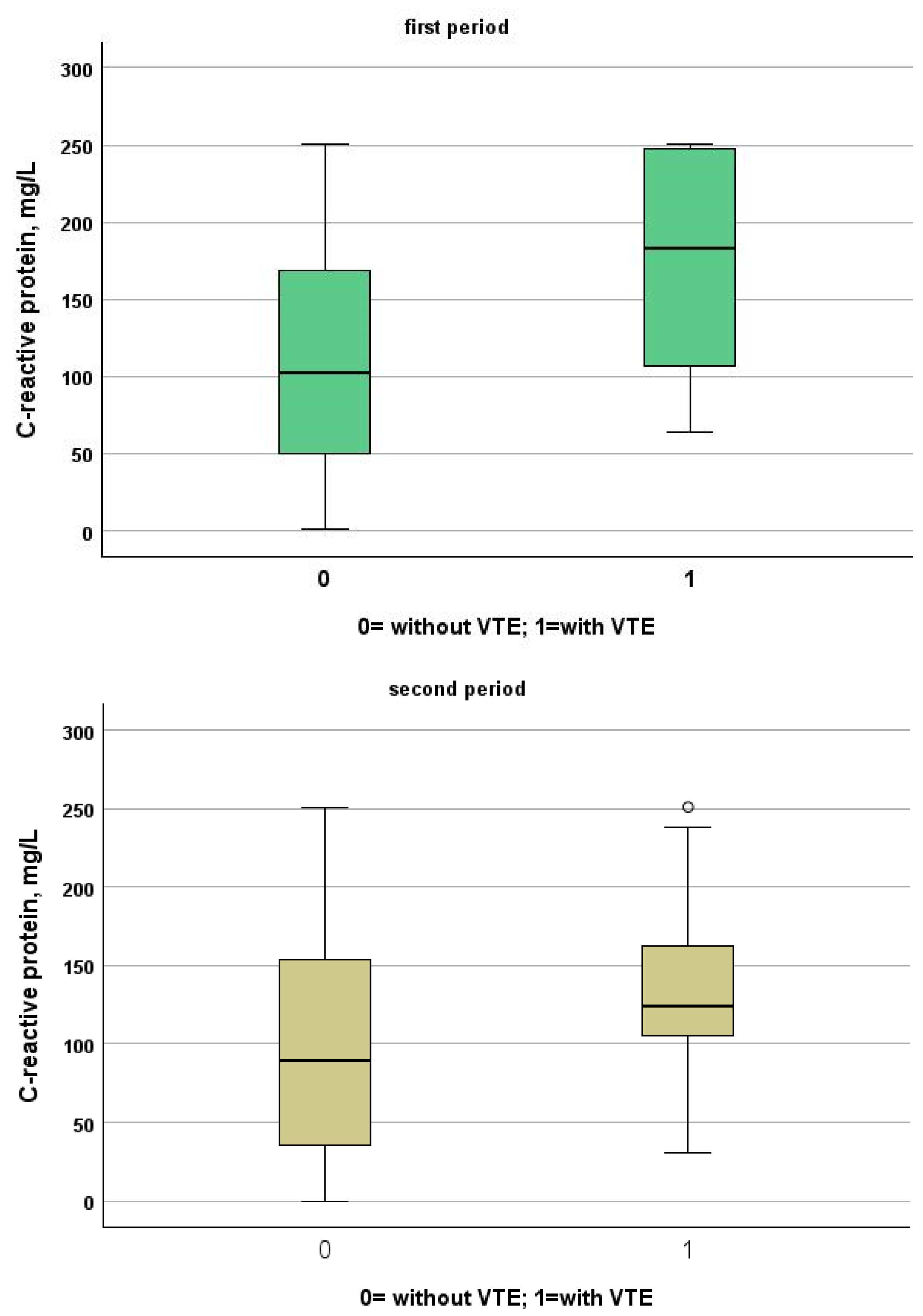

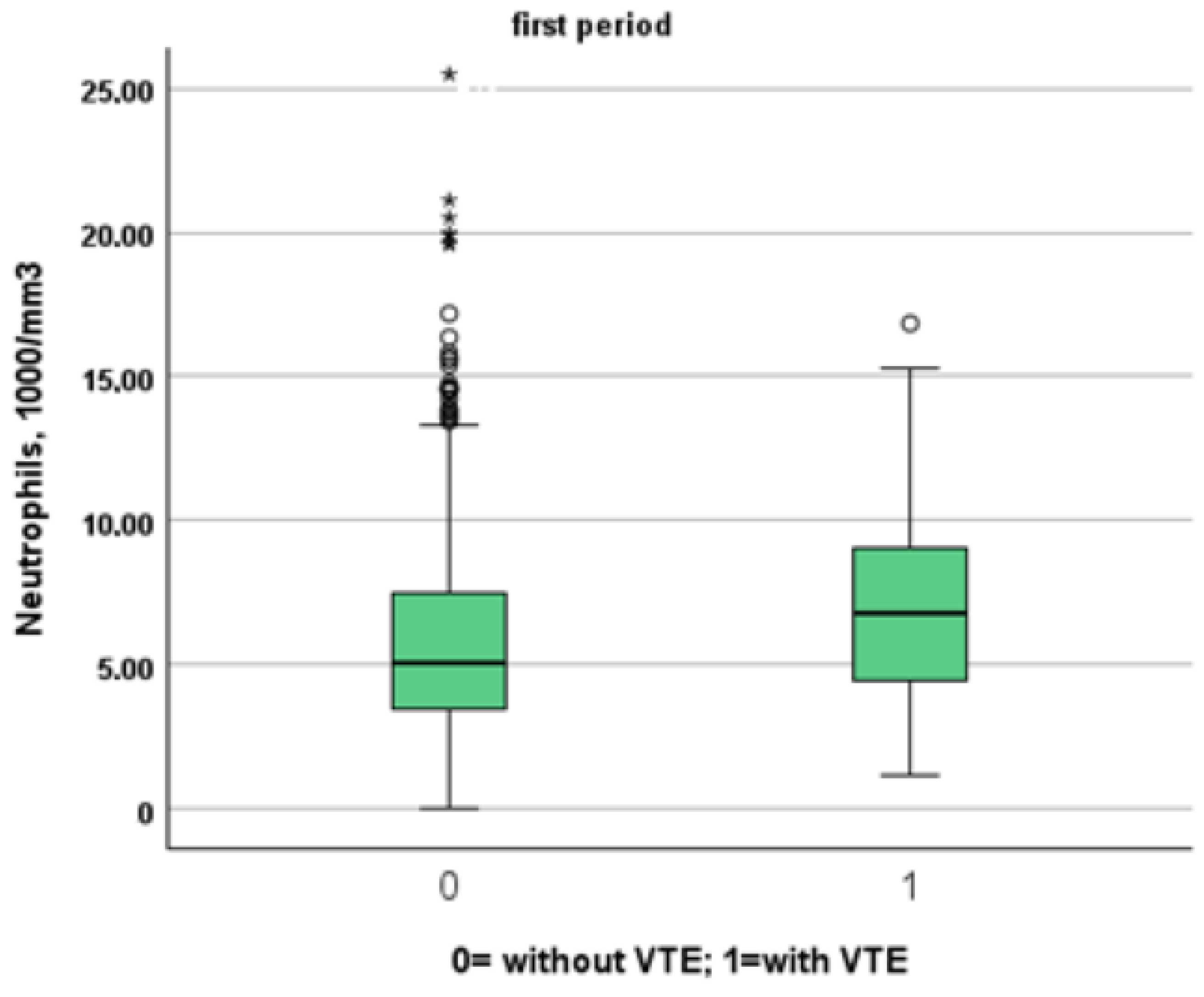

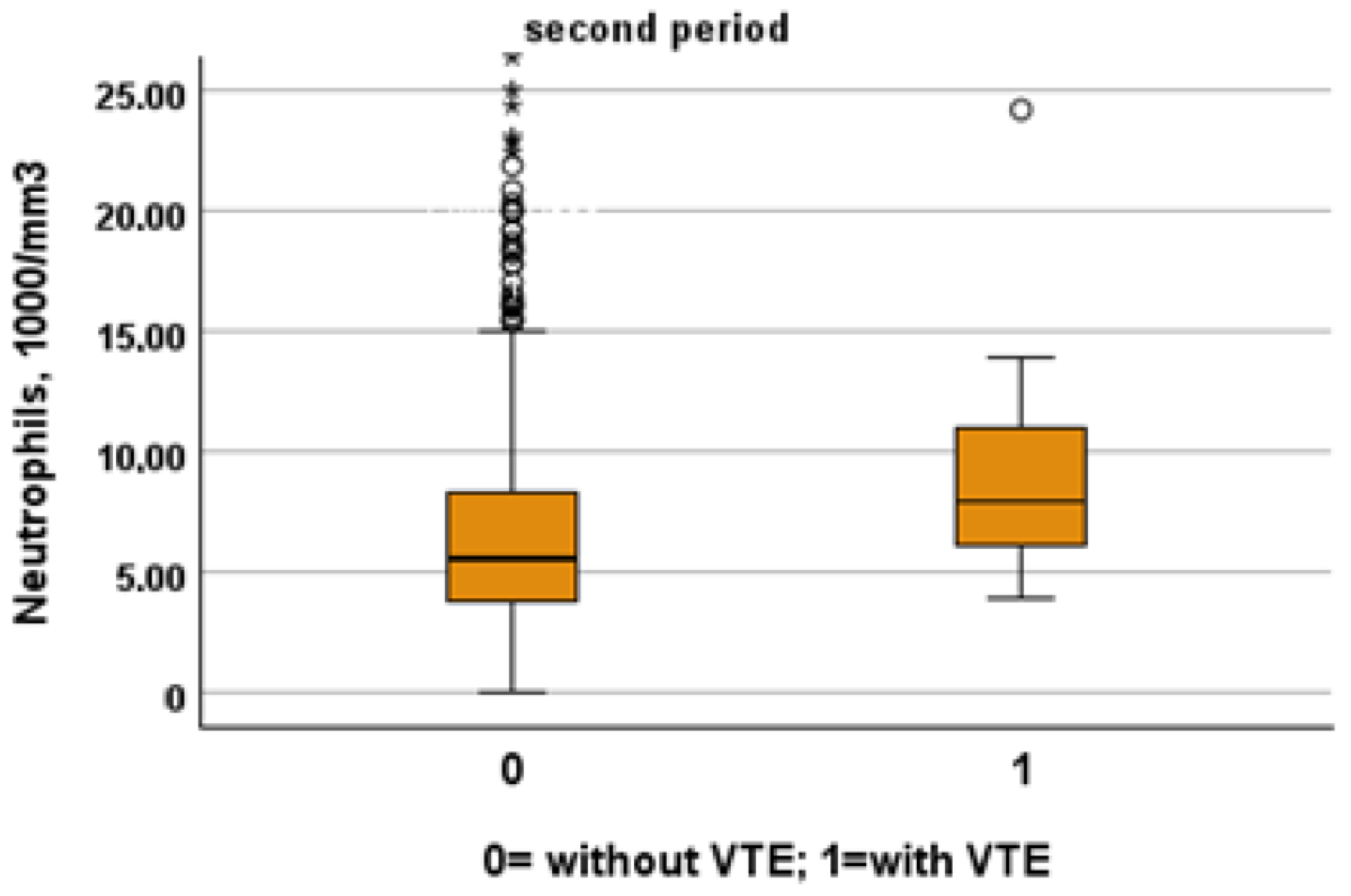

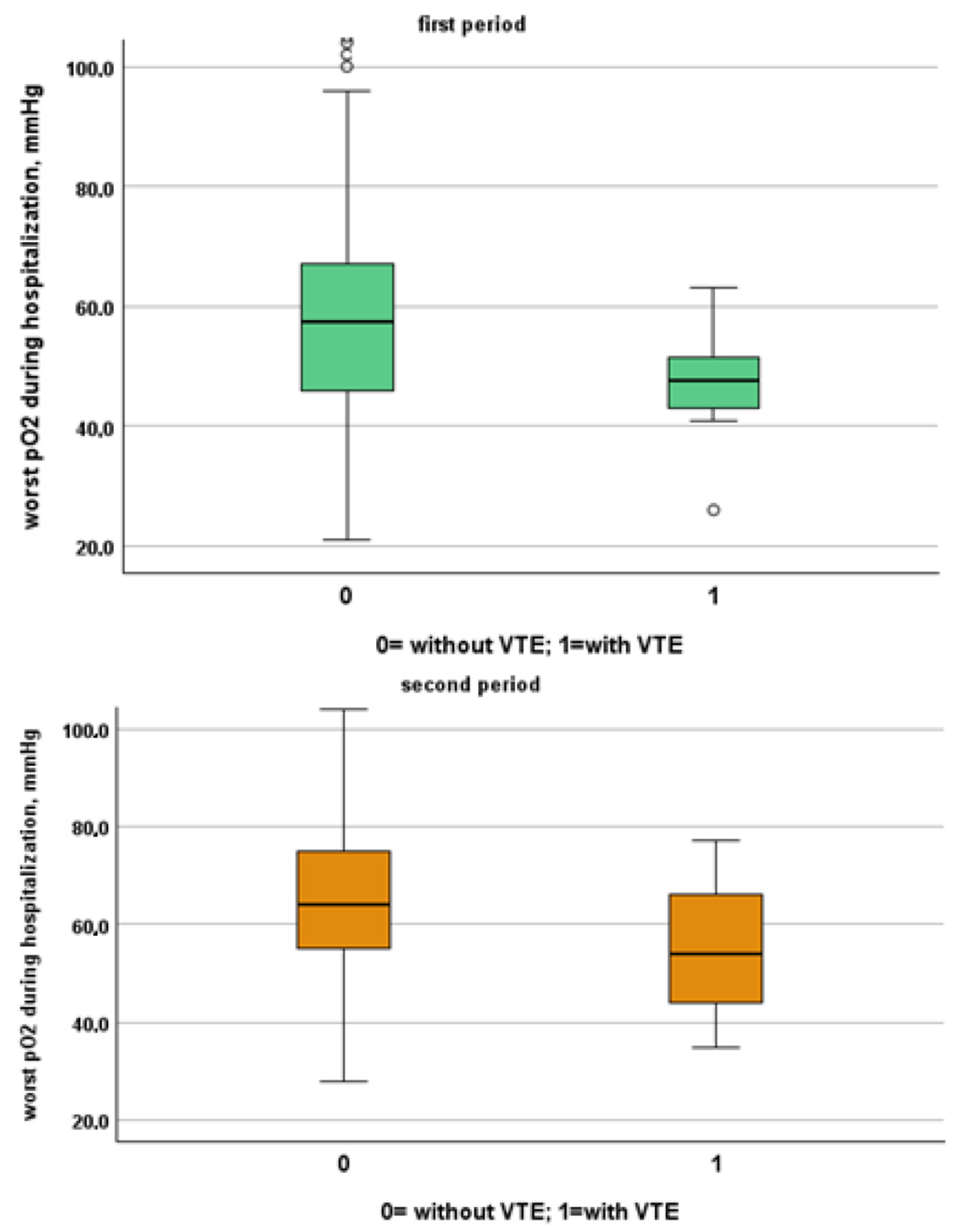

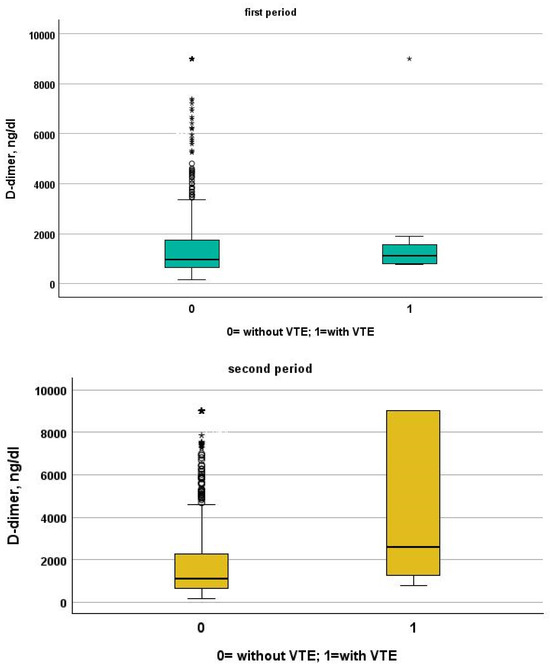

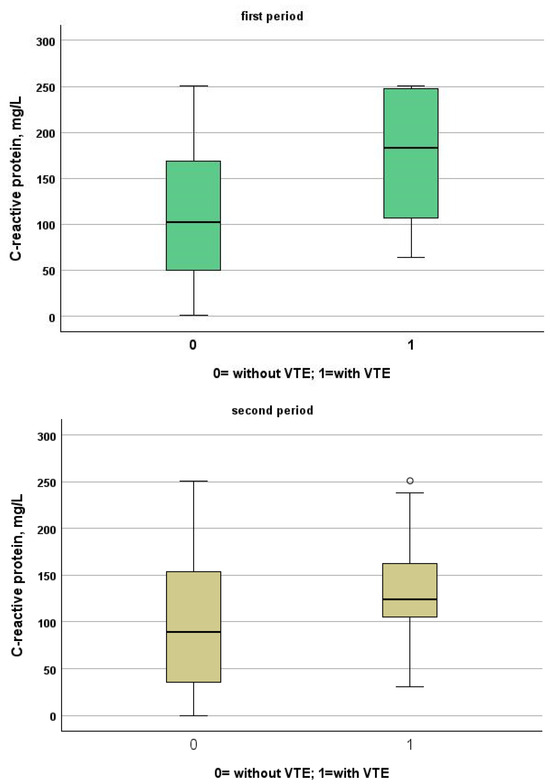

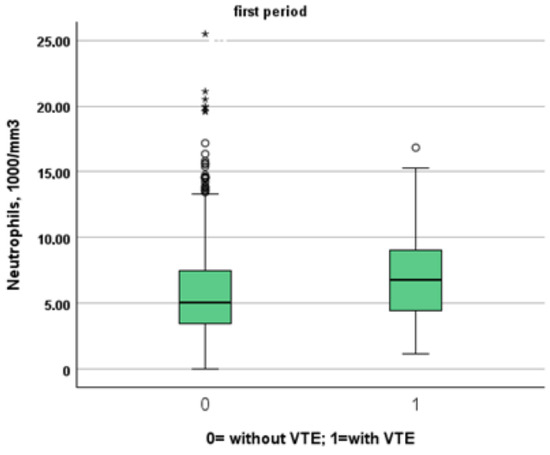

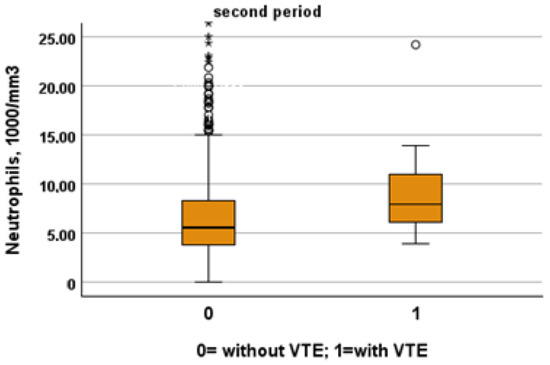

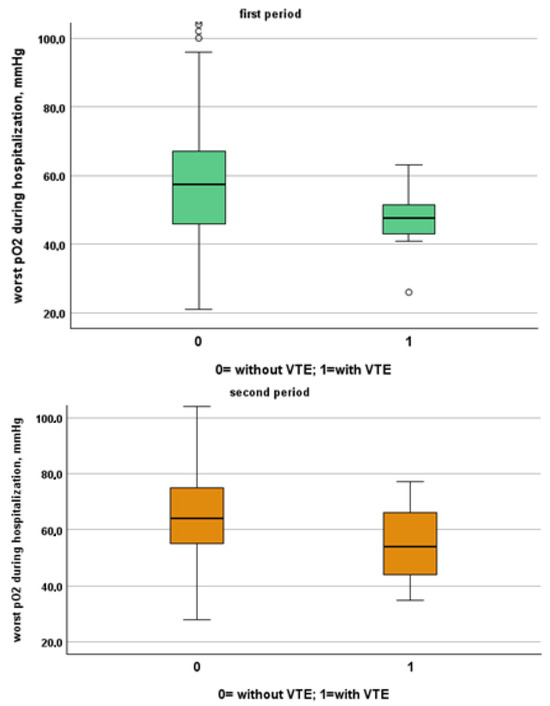

Table 3 and Table 4 show a comparison between patients of the two study periods with and without VTE. Patients from the first period were younger than patients from the second period (patients without VTE: 72, IQR 61–81 vs. 80, IQR 68–88; p < 0.001, VTE: 66, IQR 54–77 vs. 85, IQR 80–88, p = 0.001). Despite this, NIVS remains an independent risk factor for VTE in the first (OR 30.297, 95% CI 7.344–124.990, p < 0.001) and in the second period (OR 9.825, 95% CI 2.136–45.181, p = 0.003). See Table 5 and Table 6 for more details. Table 7 shows the drugs used for the treatment of VTE and their mechanism of action. Finally in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 we compare some key parameters during hospitalization in patients with and without VTE in the first and second period, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison of the main characteristics of COVID-19 presentation and outcomes between patients with and without venous thromboembolism hospitalized during the first period.

Table 4.

Comparison of the main characteristics of COVID-19 presentation and outcomes between patients with and without venous thromboembolism hospitalized during the second period.

Table 5.

Factors associated with the risk of VTE according to stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis during the first period.

Table 6.

Factors associated with the risk of VTE according to stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis during the second period.

Table 7.

Drugs used in treatments of venous thromboembolism, their pharmacodynamics and mechanism of action.

Figure 1.

Comparison between D-dimer levels in patients with and without VTE in the first and second period, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison between C-reactive protein levels in patients with and without VTE in the first and second period, respectively.

Figure 3.

Comparison between neutrophil levels in patients with and without VTE in the first and second period, respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparison between worst O2 levels during hospitalization in patients with and without VTE in the first and second period, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this retrospective study, we demonstrated that patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 during the first and second periods who experienced NIVS during hospitalization, regardless of intensive care unit (ICU) transfer, exhibited a higher risk of VTE compared to patients who did experience NIVS. Patients from the descending phase of the first pandemic wave were younger and had fewer chronic comorbidities. Despite this, the risk of VTE remained higher in NIVS patients. NIVS was used for all patients suffering from complicated forms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this sense, the use of NIVS is an indicator of severe/complicated SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, the causal effect of NIVS on VTE is linked to the severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The high incidence of VTE in critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 has been well established [16,22]; however, the incidence of VTE in patients receiving NIVS was only partially evaluated [23].

All hospitalized patients with an acute medical illness are at high VTE risk. Coagulopathy, uncontrolled inflammatory reaction and endothelial dysfunction are the main reasons for the development of thrombotic complications in SARS-CoV-2 [24]. These pathways are present at all the stages of the disease, but especially in patients requiring ICU and NIVS [18,19]. This was because patients admitted to ICUs and with an NIVS prescription have ICU-specific risk factors (sedation, immobilization and central venous catheters), and individual patient-related risk factors for VTE (obesity, age, history of personal or familial VTE, cancer, sepsis, respiratory or heart failure, stroke, trauma or recent surgery) [5,6,10]. Case series studies and case reports conducted in an ICU setting reported high VTE prevalence, particularly in patients with a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [25,26,27,28]. It has been suggested that SARS-CoV-2 in severe forms of the disease induces an excessive inflammatory state via cytokine storm combined with endothelial injury and pulmonary vascular micro thrombosis. In line with this, it has been hypothesized that the origin of the increased D-dimer is intra-alveolar fibrin deposition in the context of severe acute lung injury [29]. Finally, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia and diabetes were highly incident among both groups of patients [30]. Our results are in line with previously published evidence that found a prevalence of between 26 and 77% of PE diagnoses in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory deterioration, depending on whether they were in the emergency room, a general ward or ICU [31].

Data from our study reflect routine, unmonitored medical practice involving a broad spectrum of patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. They can, therefore, provide insights into the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 and assist in generating hypotheses. However, there are several limitations that need to be addressed. This is an observational study with a retrospective design, and no randomization to SARS-CoV-2 versus no SARS-CoV-2 patients. Thus, some non-measured variables have not been considered. We performed an extensive adjustment for several variables that may have impacted the incidence of VTE and the findings remained robust. Nevertheless, residual confounding factors may remain, as certain potential confounding variables may not have been available or may not have had the desired level of granularity. Furthermore, patients included in this study were admitted during a period of unprecedented burden of workload for the host institution, due to the large number of subjects with severe respiratory failure needing urgent admission. This circumstance required a significant and quick reorganization of all hospital activities [20]. In this setting, we cannot exclude the underdetection of VTE as a complication of COVID-19 during hospital stays. However, since all subjects included in the study underwent a chest CT before ward admission, the presence of VTE or pulmonary embolism upon admission was reliably detected. Finally, our study does not provide direct mechanistic insights into how NIVS may influence outcomes. Further research, including experimental and clinical studies, is needed to elucidate the underlying biological pathways and confirm causality.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the cumulative incidence of VTE is significantly higher in critically ill patients with a potential impact on the evolution of SARS-CoV-2. In our study, we highlight the role of uncontrolled inflammatory reactions and endothelial dysfunction as the main reasons for the development of thrombotic complications in SARS-CoV-2. In this context, patients undergoing NIVS represent a group at very high risk of developing VTE without a clear strategy regarding thromboprophylaxis. Our approach in patients with SARS-CoV-2 that receive NIVS is to initiate regular thromboprophylaxis together with active surveillance through the use of daily clinical and instrumental evaluations through compression ultrasound (CUS) or echo-color-Doppler evaluation. Future studies should evaluate whether thromboprophylaxis needs to be specifically recommended for patients with severe COVID-19 requiring NIVS.

Author Contributions

C.S., A.T., A.G., A.N., L.F., N.C., B.P., L.G. and T.M.: conception and design. C.S., A.T., A.P. and A.G.: data collection and interpretation. A.G.: data analysis. C.S. and A.T.: manuscript drafting. C.S., A.T. and T.M.: critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico dell’Area Vasta Emilia Nord, ID 273/2020/OSS/AOUPR, date of first approval 24 March 2020, amendments 19 May 2020). The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request, in accordance with the current legislation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Beckman, M.G.; Hooper, W.C.; Critchley, S.E.; Ortel, T.L. Venous thromboembolism: A public health concern. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38 (Suppl. S4), S495–S501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, G. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical patients. Circulation 2004, 110 (Suppl. S24), IV4–IV12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikdeli, B.; Monreal, M.; Jiménez, D. Pulmonary embolism in Europe remains a cause of concern despite declining deaths. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barco, S.; Mahmoudpour, S.H.; Valerio, L.; Klok, F.A.; Münzel, T.; Middeldorp, S.; Ageno, W.; Cohen, A.T.; Hunt, B.J.; Konstantinides, S.V. Trends in mortality related to pulmonary embolism in the European Region, 2000-15: Analysis of vital registration data from the WHO Mortality Database. Lancet Respir Med. 2020, 8, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollias, A.; Kyriakoulis, K.G.; Dimakakos, E.; Poulakou, G.; Stergiou, G.S.; Syrigos, K. Thromboembolic risk and anticoagulant therapy in COVID-19 patients: Emerging evidence and call for action. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 189, 846–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minet, C.; Potton, L.; Bonadona, A.; Hamidfar-Roy, R.; Somohano, C.A.; Lugosi, M.; Cartier, J.C.; Ferretti, G.; Schwebel, C.; Timsit, J.F. Venous thromboembolism in the ICU: Main characteristics, diagnosis and thromboprophylaxis. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.J.; Crooks, C.; Naja, M.; Ledlie, A.; Goulden, B.; Liddle, T.; Khan, E.; Mehta, P.; Martin-Gutierrez, L.; Waddington, K.E.; et al. COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation and escalation of patient care: A retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e594–e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.; Rad, S.; Rostami, T.; Rostami, M.; Mousavi, S.A.; Mirhoseini, S.A.; Kiumarsi, A. Hematologic predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A comparative study. Hematology 2020, 25, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollias, A.; Kyriakoulis, K.G.; Stergiou, G.S.; Syrigos, K. Heterogeneity in reporting venous thromboembolic phenotypes in COVID-19: Methodological issues and clinical implications. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 190, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, B.S.; Siguret, V.; Veyradier, A. Understanding pathophysiology of hemostasis disorders in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thachil, J.; Tang, N.; Gando, S.; Falanga, A.; Cattaneo, M.; Levi, M.; Clark, C.; Iba, T. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikdeli, B.; Madhavan, M.V.; Jimenez, D.; Chuich, T.; Dreyfus, I.; Driggin, E.; Nigoghossian, C.; Ageno, W.; Madjid, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-Up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2950–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudkerk, M.; Büller, H.R.; Kuijpers, D.; van Es, N.; Oudkerk, S.F.; McLoud, T.; Gommers, D.; van Dissel, J.; Ten Cate, H.; van Beek, E.J.R. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Thromboembolic Complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology 2020, 297, E216–E222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerotziafas, G.T.; Catalano, M.; Colgan, M.P.; Pecsvarady, Z.; Wautrecht, J.C.; Fazeli, B.; Olinic, D.M.; Farkas, K.; Elalamy, I.; Falanga, A.; et al. Guidance for the Management of Patients with Vascular Disease or Cardiovascular Risk Factors and COVID-19: Position Paper from VAS-European Independent Foundation in Angiology/Vascular Medicine. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 1597–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bompard, F.; Monnier, H.; Saab, I.; Tordjman, M.; Abdoul, H.; Fournier, L.; Sanchez, O.; Lorut, C.; Chassagnon, G.; Revel, M.P. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Capitán, C.; Barba, R.; Díaz-Pedroche, M.D.C.; Sigüenza, P.; Demelo-Rodriguez, P.; Siniscalchi, C.; Pedrajas, J.M.; Farfán-Sedano, A.I.; Olivera, P.E.; Gómez-Cuervo, C.; et al. Presenting Characteristics, Treatment Patterns, and Outcomes among Patients with Venous Thromboembolism during Hospitalization for COVID-19. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 47, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daughety, M.M.; Morgan, A.; Frost, E.; Kao, C.; Hwang, J.; Tobin, R.; Patel, B.; Fuller, M.; Welsby, I.; Ortel, T.L. COVID-19 associated coagulopathy: Thrombosis, hemorrhage and mortality rates with an escalated-dose thromboprophylaxis strategy. Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, T.; Rossi, S.; Volpi, A.; Ferrari, C.; Sverzellati, N.; Brianti, E.; Fabi, M.; Nouvenne, A.; Ticinesi, A. Reorganization of a large academic hospital to face COVID-19 outbreak: The model of Parma, Emilia-Romagna region, Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouvenne, A.; Zani, M.D.; Milanese, G.; Parise, A.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E.G.; Odone, A.; Sverzellati, N.; Meschi, T.; Ticinesi, A. Lung Ultrasound in COVID-19 Pneumonia: Correlations with Chest CT on Hospital admission. Respiration 2020, 99, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Martinez, J.; Diaz, D.; Wolowich, W.R. Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Receiving Thromboprophylaxis. J. Hematol. 2022, 11, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, J.G.; Pascual-Guardia, S.; Aguilar Colindres, R.J.; Ausín Herrero, P.; Alvarado Miranda, M.; Arita Guevara, M.; Badenes Bonet, D.; Bellido Calduch, S.; Caguana Vélez, O.A.; Cumpli Gargallo, C.; et al. Incidence of pulmonary embolism in patients with non-invasive respiratory support during COVID-19 outbreak. Respir. Med. 2021, 178, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura-Díaz, S.; Quintana-Pérez, J.V.; Gil-Boronat, A.; Herrero-Huertas, M.; Gorospe-Sarasúa, L.; Montilla, J.; Acosta-Batlle, J.; Blázquez-Sánchez, J.; Vicente-Bártulos, A. A higher D-dimer threshold for predicting pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. Emerg. Radiol. 2020, 27, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzi, G.B.; Loffi, M.; Galeazzi, G.; Gherbesi, E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: A random association? Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, B.J.; Levi, M. Re The source of elevated plasma D-dimer levels in COVID-19 infection. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 190, e133–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.J.; Liang, W.H.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.R.; Chen, Z.S.; Li, Y.M.; Liu, X.Q.; Chen, R.C.; Tang, C.L.; Wang, T.; et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: A nationwide analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, R.A.G.; Spaetgens, B.; Gietema, H.A.; Brouns, S.H.A.; Stassen, P.M.; Magdelijns, F.J.; Rennenberg, R.J.; Henry, R.M.A.; Mulder, M.M.G.; van Bussel, B.C.T.; et al. The prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 and respiratory decline: A three-setting comparison. Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).