Invisible, Uncontrollable, Unpredictable: Illness Experiences in Women with Sjögren Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Method of Information Production and Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

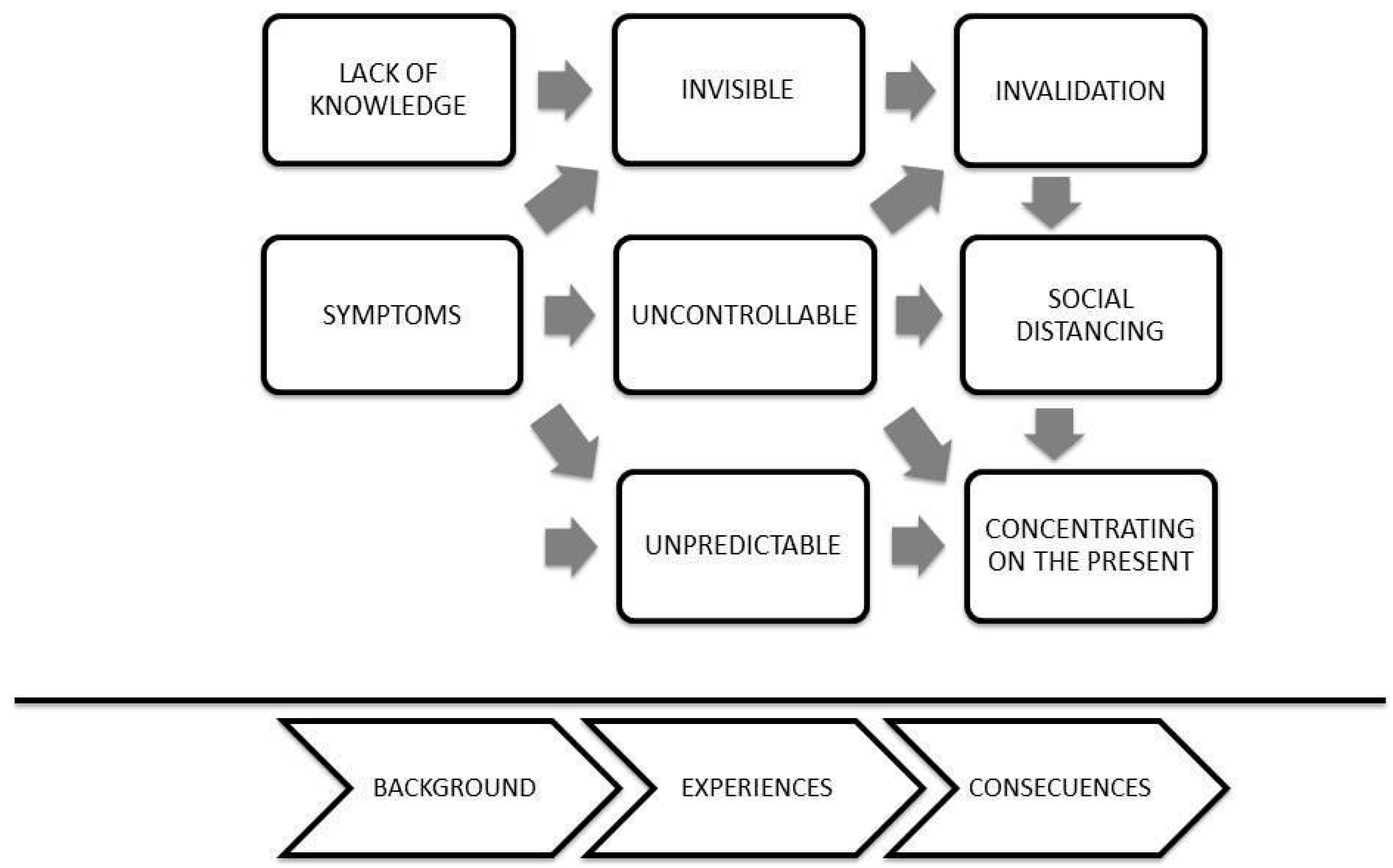

3. Results

- Invisible

The disease is sort of silent, and also, it is not something that can be seen, like external(PA: 8: 578)

You look good because ultimately you are not missing a hand or anything, you are complete, but you feel awful, meaning the process is going on inside(SA:9:1012)

The symptoms it presents are not so disabling as to worry about them(VV: 5: 893)

People think you are lazy, you know?(SA: 9:229)

I don’t get tired because I want to get tired or because I am old, I get tired because I have this thing(IV: 3: 347)

I mean, I am doing something, and I have to go lie down because I can’t anymore, I have no strength and everyone tells me, ‘you are so lazy!’(IV: 3:581)

I don’t try to explain it to anyone, nor have I told anyone, because I find it too difficult to get someone to understand me(VV: 5: 455)

I just hang out with people my age (young) and I think it is very difficult for someone to understand me, to understand that you might be tired and fatigued… in fact, my husband sometimes tells me “You were born tired! And I respond, Yes!, I take it with humor. I understand them because they have never felt this, so I say: well, how can I begin to explain it to them!(VV: 5:461)

- 2.

- Uncontrollable

There are days when I wake up with a lot of pain, and there is nothing that relieves my pain(YE: 15: 420)

There are days that I have no motivation for anything, and it is not that I have a reason, like: ah I am sad about this! There’s no reason and that is the worst of all(YE: 15: 124)

My pains went down a lot because I was not stressed(MO: 2:1298)

I have noticed that in periods of stress, after the stress passes, like, the crisis comes to me(YE15: 106)

External agents, which are work, family, worries, and problems, make you fall faster, you get more fragile when faced with the illness(PD17: 149)

You plan to do four activities and you finish one if you’re lucky. And then you end up tired, and you look and say, darn it, I have done nothing and I’m so tired, it is horrible(CM: 11: 953)

I intend to continue working, always work, for this not affect my work, I don’t think much about what can happen in the future(PB: 1: 1799)

- 3.

- Unpredictable

There are days when I wake up really well and out of nowhere, I feel bad(YE:15:116)

There are days that I wake up very well and there are days that I don’t feel like doing anything, I get up wanting to go to bed, heavy body, pain in my hands, I don’t want to do anything or let anyone speak to me, but it’s not always, it’s sometimes(YE:15:104)

You go with the pain, it is like putting on a t-shirt, a vest, a gown, I don’t know, you go all day with the pain(CM: 11: 983)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Negrini, S.; Emmi, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Murdaca, G.; Indiveri, F.; Puppo, F. Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Systemic Autoimmune Disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, I.; Zinzaras, E.; Alexiou, I.; Papathanasiou, A.A.; Davas, E.; Koutroumpas, A.; Barouta, G.; Sakkas, L.I. The Prevalence of Rheumatic Diseases in Central Greece: A Population Survey. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2010, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.; Ibrahim, G.; Holmes, G.; Hamburger, J.; Ainsworth, J. Estimating the Prevalence among Caucasian Women of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome in Two General Practices in Birmingham, UK. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 33, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldini, C.; Seror, R.; Fain, O.; Dhote, R.; Amoura, Z.; De Bandt, M.; Delassus, J.; Falgarone, G.; Guillevin, L.; Le Guern, V.; et al. Epidemiology of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome in a French Multiracial/Multiethnic Area. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvarnström, M.; Ottosson, V.; Nordmark, B.; Wahren-Herlenius, M. Incident Cases of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome during a 5-Year Period in Stockholm County: A Descriptive Study of the Patients and Their Characteristics. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 44, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. Sjogren’s Syndrome: A Community-Based Study of Prevalence and Impact. Rheumatology 1998, 37, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Theander, E.; Baldini, C.; Seror, R.; Retamozo, S.; Quartuccio, L.; Bootsma, H.; Bowman, S.J.; Dörner, T.; Gottenberg, J.-E.; et al. Early Diagnosis of Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: EULAR-SS Task Force Clinical Recommendations. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 12, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, B.; Bowman, S.J.; Fox, P.C.; Vivino, F.B.; Murukutla, N.; Brodscholl, J.; Ogale, S.; McLean, L. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Health Experiences and Predictors of Health Quality among Patients in the United States. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsons, S. A Review and Update of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Am. J. Manag. Care 2001, 7, S433–S443. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, N.; Vivino, F.; Baker, J.; Dunham, J.; Pinto, A. Risk Factors for Caries Development in Primary Sjogren Syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Brito-Zeron, P.; Solans, R.; Camps, M.-T.; Casanovas, A.; Sopena, B.; Diaz-Lopez, B.; Rascon, F.-J.; Qanneta, R.; Fraile, G.; et al. Systemic Involvement in Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome Evaluated by the EULAR-SS Disease Activity Index: Analysis of 921 Spanish Patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Rheumatology 2014, 53, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojan, G.; Baer, A.N.; Danoff, S.K. Pulmonary Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013, 13, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priori, R.; Minniti, A.; Derme, M.; Antonazzo, B.; Brancatisano, F.; Ghirini, S.; Valesini, G.; Framarino-dei-Malatesta, M. Quality of Sexual Life in Women with Primary Sjögren Syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, E.C. Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Manifestations of Sjogren Syndrome. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 46, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Srinivas, B.H.; Emmanuel, D.; Jain, V.K.; Parameshwaran, S.; Negi, V.S. Renal Involvement in Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.; Zdebik, A.; Ciurtin, C.; Walsh, S.B. Renal Involvement in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, H.; Mariette, X. Renal Involvement in Primary Sjögren Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.; Johnston, M.; Baum, A. The SAGE Handbook of Health Psychology; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, S.J.; Booth, D.A.; Platts, R.G. Measurement of Fatigue and Discomfort in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Using a New Questionnaire Tool. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldorsen, K.; Bjelland, I.; Bolstad, A.; Jonsson, R.; Brun, J. A Five-Year Prospective Study of Fatigue in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddali Bongi, S.; Del Rosso, A.; Orlandi, M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Gynaecological Symptoms and Sexual Disability in Women with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome and Sicca Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013, 31, 683–690. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanski, A.-L.; Tomiak, C.; Pleyer, U.; Dietrich, T.; Burmester, G.R.; Dörner, T. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottenberg, J.-E.; Ravaud, P.; Puéchal, X.; Le Guern, V.; Sibilia, J.; Goeb, V.; Larroche, C.; Dubost, J.-J.; Rist, S.; Saraux, A.; et al. Effects of Hydroxychloroquine on Symptomatic Improvement in Primary Sjögren Syndrome: The JOQUER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2014, 312, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flick, U. Introducción a La Investigación Cualitativa, 3rd ed.; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Alcayaga, G.; Herrera, A.; Espinoza, I.; Rios-Erazo, M.; Aguilar, J.; Leiva, L.; Shakhtur, N.; Wurmann, P.; Geenen, R. Illness Experience and Quality of Life in Sjögren Syndrome Patients. IJERPH 2022, 19, 10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a Los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lempp, H.; Kingsley, G. Qualitative Assessments. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 21, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.Y.J.; Thomson, W.M. An Update on the Lived Experience of Dry Mouth in Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients. Front. Oral. Health 2021, 2, 767568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-203-79320-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Fernandez, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de La Investigacion, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Perella, C.; Steenackers, M.; Robbins, B.; Stone, L.; Gervais, R.; Schmidt, T.; Goswami, P. Patient Experience of Sjögren’s Disease and Its Multifaceted Impact on Patients’ Lives. Rheumatol. Ther. 2023, 10, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gera, C.; Kumar, N. Otolaryngologic Manifestations of Various Rheumatic Diseases: Awareness and Practice Among Otolaryngologists. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 67, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, D.; Thomaes, S.; Kool, M.B.; Van Middendorp, H.; Lumley, M.A.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Geenen, R. A Combination of Illness Invalidation from the Work Environment and Helplessness Is Associated with Embitterment in Patients with FM. Rheumatology 2012, 51, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.Y.J.; Thomson, W.M.; Nolan, A.; Ferguson, S. The Lived Experience of Sjögren’s Syndrome. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli, K.; Livas, C.; Vissink, A.; Spijkervet, F. Is YouTube Useful as a Source of Information for Sjögren’s Syndrome? Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kool, M.B.; Van Middendorp, H.; Boeije, H.R.; Geenen, R. Understanding the Lack of Understanding: Invalidation from the Perspective of the Patient with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kool, M.B.; Van Middendorp, H.; Lumley, M.A.; Schenk, Y.; Jacobs, J.W.G.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Geenen, R. Lack of Understanding in Fibromyalgia and Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Illness Invalidation Inventory (3*I). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1990–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, N.; Kool, M.; Estévez-López, F.; López-Chicheri, I.; Geenen, R. The Potential Buffering Role of Self-Efficacy and Pain Acceptance against Invalidation in Rheumatic Diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walihagen, M.I.; Brod, M.; Reimer, M.; Lindgren, C.L. Perceived Control and Well-Being in Parkinson’s Disease. West. J. Nurs. Res. 1997, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, K.; Littlejohn, G.O. Psychological Control Is a Key Modulator of Fibromyalgia Symptoms and Comorbidities. JPR 2012, 5, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mills, S.D.; Azizoddin, D.; Gholizadeh, S.; Racaza, G.Z.; Nicassio, P.M. The Mediational Role of Helplessness in Psychological Outcomes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2018, 27, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samwel, H.J.A.; Evers, A.W.M.; Crul, B.J.P.; Kraaimaat, F.W. The Role of Helplessness, Fear of Pain, and Passive Pain-Coping in Chronic Pain Patients. Clin. J. Pain 2006, 22, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viane, I.; Crombez, G.; Eccleston, C.; Devulder, J.; De Corte, W. Acceptance of the Unpleasant Reality of Chronic Pain: Effects upon Attention to Pain and Engagement with Daily Activities. Pain 2004, 112, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Davies, M.; Scott, W.; Paroli, M.; Harris, S.; Sanderson, K. Can a Psychologically Based Treatment Help People to Live with Chronic Pain When They Are Seeking a Procedure to Reduce It? Pain Med. 2015, 16, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.L.; Davis, M.C.; Zautra, A.J. Pain Acceptance Moderates the Relation between Pain and Negative Affect in Female Osteoarthritis and Fibromyalgia Patients. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeven, E.W.M.; De Klerk, S.; Kraaimaat, F.W.; Van De Kerkhof, P.C.M.; De Jong, E.M.G.J.; Evers, A.W.M. Biopsychosocial Mechanisms of Chronic Itch in Patients with Skin Diseases: A Review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2008, 88, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, A.; Ficjan, A.; Stradner, M.H.; Hermann, J.; Unger, J.; Stamm, T.; Stummvoll, G.; Dür, M.; Graninger, W.B.; Dejaco, C. It’s More than Dryness and Fatigue: The Patient Perspective on Health-Related Quality of Life in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome—A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera, A.; Leiva, L.; Espinoza, I.; Ríos-Erazo, M.; Shakhtur, N.; Wurmann, P.; Rojas-Alcayaga, G. Invisible, Uncontrollable, Unpredictable: Illness Experiences in Women with Sjögren Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113228

Herrera A, Leiva L, Espinoza I, Ríos-Erazo M, Shakhtur N, Wurmann P, Rojas-Alcayaga G. Invisible, Uncontrollable, Unpredictable: Illness Experiences in Women with Sjögren Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(11):3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113228

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera, Andrea, Loreto Leiva, Iris Espinoza, Matías Ríos-Erazo, Nailah Shakhtur, Pamela Wurmann, and Gonzalo Rojas-Alcayaga. 2024. "Invisible, Uncontrollable, Unpredictable: Illness Experiences in Women with Sjögren Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 11: 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113228

APA StyleHerrera, A., Leiva, L., Espinoza, I., Ríos-Erazo, M., Shakhtur, N., Wurmann, P., & Rojas-Alcayaga, G. (2024). Invisible, Uncontrollable, Unpredictable: Illness Experiences in Women with Sjögren Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(11), 3228. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113228