The Role of Different Medical Therapies in the Management of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.3. Outcomes and Data Extraction

2.3.1. Primary Outcomes

- (1)

- Dysmenorrhea: Evaluation of dysmenorrhea using standardized measures (10-point visual analogue scale (VAS), with conversion to a 10-point scale in case studies reporting a 1–100 mm scale) to score the symptom intensity from baseline to follow-up period;

- (2)

- HMB: Assessed at baseline and at follow-up after the treatment by compiling a menstrual diary, taking into account the number of bleeding days, or by assessing the volume of blood lost per menstruation;

- (3)

- Changes in uterine volume: Determining ultrasonographically the volume of the uterus at baseline and at a time interval after the beginning of therapy.

2.3.2. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics and Quality of Evidence

3.3. Study Outcomes

3.3.1. Changes in Dysmenorrhea

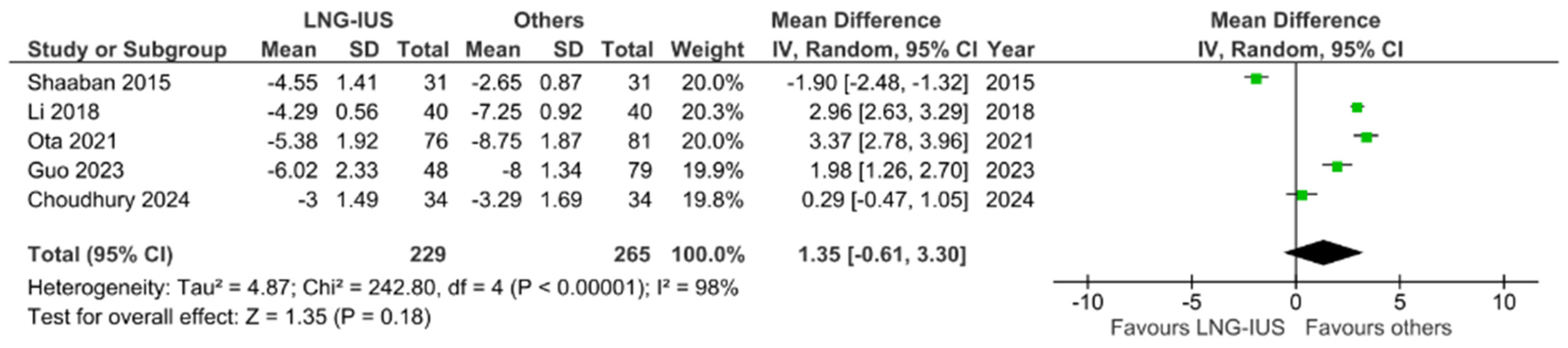

3.3.2. Changes in Uterine Volume

3.3.3. Changes in Bleeding Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cunningham, R.K.; Horrow, M.M.; Smith, R.J.; Springer, J. Adenomyosis: A Sonographic Diagnosis. Radiographics 2018, 38, 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.-W. Clinical Profiles of 710 Premenopausal Women with Adenomyosis Who Underwent Hysterectomy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antero, M.F.; Ayhan, A.; Segars, J.; Shih, I.-M. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Adenomyosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2020, 38, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Daguati, R.; Abbiati, A.; Fedele, L. Adenomyosis: Epidemiological Factors. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 20, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannoni, L.; Del Forno, S.; Raimondo, D.; Arena, A.; Giaquinto, I.; Paradisi, R.; Casadio, P.; Meriggiola, M.C.; Seracchioli, R. Adenomyosis and Endometriosis in Adolescents and Young Women with Pelvic Pain: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Minerva Pediatr. 2024, 76, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzauti, S.; Lazzeri, L.; Tosti, C.; Centini, G.; Orlandini, C.; Luisi, S.; Zupi, E.; Exacoustos, C.; Petraglia, F. Transvaginal Sonographic Features of Diffuse Adenomyosis in 18–30-Year-Old Nulligravid Women without Endometriosis: Association with Symptoms. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 46, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzii, L.; Galati, G.; Mattei, G.; Chinè, A.; Perniola, G.; Di Donato, V.; Di Tucci, C.; Palaia, I. Expectant, Medical, and Surgical Management of Ovarian Endometriomas. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Zhang, W.Y.; Zhang, J.P.; Lu, D. The LNG-IUS Study on Adenomyosis: A 3-Year Follow-up Study on the Efficacy and Side Effects of the Use of Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System for the Treatment of Dysmenorrhea Associated with Adenomyosis. Contraception 2009, 79, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragheto, A.M.; Caserta, N.; Bahamondes, L.; Petta, C.A. Effectiveness of the Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System in the Treatment of Adenomyosis Diagnosed and Monitored by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Contraception 2007, 76, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Frontino, G.; De Giorgi, O.; Pietropaolo, G.; Pasin, R.; Crosignani, P.G. Continuous Use of an Oral Contraceptive for Endometriosis-Associated Recurrent Dysmenorrhea That Does Not Respond to a Cyclic Pill Regimen. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettel, M.; Breitbarth, H.; Elger, W.; Gräser, T.; Hübler, D.; Kaufmann, G.; Moore, C.; Patchev, V.; Römer, W.; Schröder, J.; et al. The Pharmacological Profile of Dienogest. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 1999, 4, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.R.; Corson, S.L. Long-Term Management of Adenomyosis with a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist: A Case Report. Fertil. Steril. 1993, 59, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.M.; Elnashar, A.M.; Mosbah, A.A. Aromatase Inhibitors or Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists for the Management of Uterine Adenomyosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Naftalin, J.; Hoo, W.; Pateman, K.; Mavrelos, D.; Holland, T.; Jurkovic, D. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 3432–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, O.M.; Ali, M.K.; Sabra, A.M.A.; Abd El Aal, D.E.M. Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System versus a Low-Dose Combined Oral Contraceptive for Treatment of Adenomyotic Uteri: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Contraception 2015, 92, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, M.; Mesbah, Y. Comparison of Dienogest versus Triptorelin Acetate in Premenopausal Women with Adenomyosis: A Prospective Clinical Trial. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 292, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Feng, W.-W.; Hua, K.-Q. Drug Therapy for Adenomyosis: A Prospective, Nonrandomized, Parallel-Controlled Study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 1855–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuga, Y.; Fujimoto-Okabe, H.; Hagino, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Dienogest in the Treatment of Painful Symptoms in Patients with Adenomyosis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Study. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, T.; Akira, S.; Fukami, T.; Yoneyama, K.; Takeshita, T. Efficacy of Hormonal Therapies for Decreasing Uterine Volume in Patients with Adenomyosis. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2018, 7, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.I.; Youssef, A.A.; Yousef, A.M.; Ali, M.K. Comparison of Dienogest versus Combined Oral Contraceptive Pills in the Treatment of Women with Adenomyosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 154, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capmas, P.; Brun, J.-L.; Legendre, G.; Koskas, M.; Merviel, P.; Fernandez, H. Ulipristal Acetate Use in Adenomyosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, I.; Taniguchi, F.; Ota, Y.; Nagata, H.; Wada, I.; Nakaso, T.; Ikebuchi, A.; Sato, E.; Azuma, Y.; Harada, T. A Controlled Clinical Trial Comparing Potent Progestins, LNG-IUS and Dienogest, for the Treatment of Women with Adenomyosis. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2021, 20, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Lin, Y.; Hu, S.; Shen, Y. Compare the Efficacy of Dienogest and the Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System in Women with Adenomyosis. Clin. Ther. 2023, 45, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, W.; He, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J.; Dong, J.; Xu, J.; et al. Effect of Mifepristone vs Placebo for Treatment of Adenomyosis with Pain Symptoms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2317860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.; Jena, S.K.; Mitra, S.; Padhy, B.M.; Mohakud, S. Comparison of Efficacy between Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System and Dienogest in Adenomyosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2024, 18, 26334941241227401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Country | Study Period | Study Design | Patients Number | Age Mean (Years) | Comparison | Follow Up | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badawy et al., 2012 [13] | Egypt | December 2005 to January 2010 | Randomized clinical trial | 32 | AI 37 ± 3.44 | Aromatase inhibitors/ GnRH agonists | 4, 8, and 12 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume |

| GnRH agonists 35 ± 2.8 | ||||||||

| Shaaban et al., 2015 [16] | Egypt | August 2013 to November 2014. | Randomized clinical trial | 62 | LNG-IUS 39.39 ± 4.43 | LNG-IUS/COC | 6 months | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, menstrual bleeding, increase in blood flow resistance |

| COC 39.16 ± 3.21 | ||||||||

| Fawzy et al., 2015 [17] | Egypt | May 2013 to November 2014 | Prospective clinical trial | 41 | DNG 39.8 ± 4.3 | Dienogest/GnRH agonists | 16 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, menorrhagia, Hb (gm/dL), Ferritin (ng/mL) |

| GnRH agonists 40.2 ± 5.7 | ||||||||

| Li et al., 2017 [18] | China | February 2015 to February 2016 | Prospective parallel-controlled study | 200 | GnRH agonists 36.28 | GnRH agonists/LNG-IUS | 3, 6, and 12 months | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume |

| LNG-IUS 40.45 | ||||||||

| Osuga et al., 2017 [19] | Japan | August 2014 to June 2015 | Randomized clinical trial | 68 | DNG 37.3 ± 7.9 | Dienogest/placebo | 16 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume |

| PL 37.4 ± 6.6 | ||||||||

| Matsushima et al., 2018 [20] | Japan | August 2007 to July 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 28 | GnRH agonists 40.0 ± 6.1 | GnRH agonists/COC/dienogest | 16 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, Menorrhagia, CA125 (U/mL) |

| COC 37.7 ± 5.3 | ||||||||

| DNG 38.9 ± 7.8 | ||||||||

| Hassanin et al., 2020 [21] | Egypt | March 2019 to August 2020 | Randomized clinical trial | 97 | COC 40.36 ± 3.73 | COC/dienogest | 6 months | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, ovarian volume, artery RI and PI |

| DNG 39.96 ± 3.87 | ||||||||

| Capmas et al., 2020 [22] | France | June 2016 to February 2018 | Randomized controlled study, double-blind | 40 | UA 43 (37–45) | Ulipristal acetate/placebo | 5, 9, and 13 weeks and 6 months | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, anemia, quality of life |

| PL 42.5 (39–47) | ||||||||

| Ota et al., 2021 [23] | Japan | January 2013 to December 2020 | Prospective clinical trial | 157 | LNG-IUS 42.3 ± 4.2 | LNG-IUS/dienogest | 72 months | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, bone mineral density (BMD) |

| DNG 41.4 ± 3.5 | ||||||||

| Guo et al., 2023 [24] | China | May 2019 to June 2022 | Randomized clinical trial | 117 | LNG-IUS 39.3 (5.2) | LNG-IUS/dienogest | 36 months | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, CA125, endometrial thickness, FSH, LH |

| DNG 39.7 (6.3) | ||||||||

| Che et al., 2023 [25] | China | May 2018 to April 2019 | Randomized clinical trial | 134 | MF 40.2 [4.6] | Mifepristone/placebo | 12 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, uterine volume, menorrhagia, anemia, CA125, platelet count |

| PL 41.7 [5.0] | ||||||||

| Choudhury et al., 2024 [26] | India | June 2020 to August 2021 | Randomized clinical trial | 74 | LNG-IUS 40.06 ± 6.95 | LNG-IUS/dienogest | 12 weeks | Dysmenorrhea, menstrual blood loss, quality of life |

| DNG 40.97 ± 6.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galati, G.; Ruggiero, G.; Grobberio, A.; Capri, O.; Pietrangeli, D.; Recine, N.; Vignali, M.; Muzii, L. The Role of Different Medical Therapies in the Management of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113302

Galati G, Ruggiero G, Grobberio A, Capri O, Pietrangeli D, Recine N, Vignali M, Muzii L. The Role of Different Medical Therapies in the Management of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(11):3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113302

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalati, Giulia, Gianfilippo Ruggiero, Alice Grobberio, Oriana Capri, Daniela Pietrangeli, Nadia Recine, Michele Vignali, and Ludovico Muzii. 2024. "The Role of Different Medical Therapies in the Management of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 11: 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113302

APA StyleGalati, G., Ruggiero, G., Grobberio, A., Capri, O., Pietrangeli, D., Recine, N., Vignali, M., & Muzii, L. (2024). The Role of Different Medical Therapies in the Management of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(11), 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113302